Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

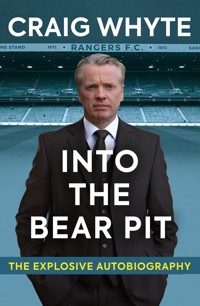

From being the most dominant club in Scottish football history, Rangers F.C., one of the most famous and powerful names in British sport, was sold to venture capitalist Craig Whyte in 2011 . . . for £1. When Whyte walked through the gates at Ibrox, the club was mired in debt and plagued with a toxic culture which seeped everywhere – from the corridors of power to a sectarian hard core in the stands. The 'great Whyte hope' was touted for a time as Rangers' saviour but he was soon hung out to dry as the fall guy for Rangers' misery as the unthinkable happened. The club was plunged into liquidation and the reformed club suffered the indignity of demotion to the third division, the lowest echelon of Scottish professional football. The demise of Rangers saw Whyte's reputation eviscerated on the pages of every newspaper in the country, his name vilified on radio shows, TV programmes and blogs as every aspect of his professional and personal life was picked over. In 2012 he was arrested and accused of fraud. He was put on trial where he faced the full might and resources of the government for his role in the downfall of the club. Although he was ultimately acquitted of all charges, he had to endure years of false accusations from some media outlets and multiple death threats from obsessed fans. Full of startling revelations, this is the previously untold story of greed, corruption and scandal at the heart of Rangers F.C., told, definitively, by the man who was at the very centre of the storm.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2020 by

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Text copyright © Craig Whyte and Douglas Wight, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-909715-64-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78885-103-9

The right of Craig Whyte and Douglas Wight to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on requestfrom the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburgh

Printed in Great Britain by Bell and Bain, Glasgow

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

EPILOGUE

PROLOGUE

IBROX, GLASGOW, 7 MAY, 2011

It was no use. We were stuck. There were fans everywhere, blocking the road.

‘Let’s just walk from here, shall we?’ I said to the others in our taxi.

We stepped out into Edmiston Drive, gesturing to the guys in the taxi behind to do the same. Surrounding us were people clad in blue, white and red. Looming ahead, dominating the skyline to our left, was Ibrox Stadium, home of Rangers FC – the club which, as of yesterday afternoon, I owned.

It was my first visit to the ground since completing the takeover from David Murray. And it was match day. There were just three games to the end of the season. It was nip and tuck between Rangers and Celtic, as it always seemed to be, but three wins and the title was ours. Starting today, at home against Hearts in a lunchtime kick-off.

We’d only walked a few paces when people started to recognise me. You could hear a few murmurs. ‘There he is’. ‘That’s Craig Whyte’. Then it started to build. Some fans started chanting. Many broke into applause. A few shook my hand and wanted their photo taken.

My first taste of what owning Rangers might mean had come just a couple of hours after signing the paperwork in David Murray’s office in Edinburgh. My team and I had caught the train to Glasgow. It seemed the obvious way to travel between the cities, but seeing the new owner of Rangers on a busy commuter train was clearly surprising for some. By the time we arrived there were TV cameras waiting. That reception, however, was nothing compared to this.

As we walked towards the ground and the imposing structure of the Archibald Leitch-designed Bill Struth Main Stand – property that now belonged to me – we had a problem. How did we actually get in?

We asked a police officer. ‘We’ll get someone to escort you in,’ came the reply.

The next thing we knew we were flanked by two mounted cops. We were now swept along on a wave of good feeling. The BBC reporter Chris McLaughlin caught up with me as we walked towards the ground. ‘How does it feel,’ he asked, ‘to be walking inside Ibrox for the first time as owner?’

‘Very exciting,’ I replied. And it was. I could scarcely believe it was happening. To think a lad from Motherwell, who first went to see Rangers as a boy, could one day return to run the club. My dad, Tom, who in many ways was responsible for sparking my interest in both football and business, was among those accompanying me on this special day.

Asked about my priorities, both immediate and looking ahead, I told the reporter what my hopes were – that we would win that day and go on to win the league and that there were exciting times ahead.

As I reached the main entrance at the front of the stand, I turned and gave the assembled fans a wave. In response they gave a huge cheer. The sun was splitting the sky. It was a great day for football. In that moment it was impossible not to feel the overwhelmingly positive mood of the day.

Once I was inside the door, the chief executive, Martin Bain, was there to greet me. Given he had been one of the directors who didn’t want my deal to go ahead, his presence here seemed charming. He shook my hand and asked if there was anything he could do for me.

‘The first thing you can do is get that statement off the club’s website,’ I told him. Bain was a member of the independent board committee, a group set up apparently to safeguard the interests of the thousands of minority shareholders who made up 15 per cent of the total. No sooner had the ink dried on my deal with Murray than the committee put out a statement on the Rangers website saying they did not support the takeover and they didn’t think the money was there to support the cashflow.

To say I was annoyed was an understatement. These guys were working for me now. I was going to have to put out my own statement saying what a load of nonsense it was and that some people had their own agendas – hardly the best start to a new regime.

The actions of that committee had been one of the reasons why, as the takeover edged toward completion, I had been considering walking away. I had never known a deal like this one. It was a big distraction. At one stage I’d instructed my lawyer, Gary Withey, to tell Murray’s team that if it didn’t go through quickly I was out.

It had been a lot of hassle, all this bullshit with self-important people thinking they had a say in things. Even at the last minute they had found ways to obstruct proceedings, delaying the original signatures the previous Thursday night. In the end I think it was David Murray who ordered Bain and the finance director, Donald McIntyre, to sign control over to me and my colleague, Phil Betts.

What none of us knew at the time was just how desperate David Murray was to get the deal over the line.

It wasn’t the day for any unnecessary unpleasantness, however. Martin Bain left and the statement was taken down immediately. When he returned he joined my guests and I in the directors’ room for a cup of tea before kick-off. He was pleasant enough. He told me there was a special seat for the owner of the club, and he showed me where it was.

We were civil to each other, but I think we both knew his days were numbered. The same would go for any other dissenters on the independent committee.

The match itself couldn’t have gone better. Rangers were up against a depleted Hearts side, once again embroiled in speculation that the club’s eccentric owner, Vladimir Romanov, was interfering in team selection. The Lithuania-based businessman had entered Scottish football with a bang but, despite some success, had made more enemies than friends. I hoped his experience wasn’t a cautionary tale for the league’s newest owner. Rangers comfortably won 4-0. The title was within touching distance.

After the match I held a press conference in the Blue Room. I wanted to carry on the positive feeling I had felt from the stands. The last thing I wanted to do was upset the team’s title charge, so I talked of funds being available for new players and my belief that we could win the tax case which loomed ominously on the horizon. They weren’t empty promises. At the time of the takeover I sincerely believed there wasn’t a single problem facing the club that was insurmountable.

However, in most business deals of this nature, it’s usual to be allowed access to the premises, to see what kind of company you are acquiring, to kick the tyres. That hadn’t happened here.

It was only when the crowds had dispersed and the clamour about my arrival had died down that I got a chance to step out on to the pitch and survey my new surroundings. I thought of the times I’d sat in the stands – first in the Copland Road end and then in the Club Deck – watching David Murray’s Rangers revolution take shape, the team’s success mirroring my own upturn in fortune. My predecessor had brought elite foreign players to Rangers; he had reversed the club’s policy by signing Catholics and had delivered nine-in-a-row. But what club had he left me? I still wasn’t sure.

I thought also of the fans, whose rousing reception still rang in my ears.

Thanks to sections of the media, which had wrongly painted me as a billionaire, many of them no doubt believed I was going to invest heavily in their club. That was never the reality and I had never said as much. But as I looked around the stands I hoped would be filled with 50,000 joyous supporters in the seasons to come, I had an ominous feeling that my failure to be upfront about the challenges that lay ahead could come back to haunt me.

They didn’t know the pressure I had been under from David Murray to spin as positive a line as possible: to praise his stewardship, to talk up the funds we might invest, to assure the fans that it was all going to be hunky-dory.

I had seen the expectation in the fans’ eyes. Were these people going to end up disappointed? Transforming Rangers was my sole intention. But I felt they didn’t appreciate what lay ahead. Perhaps I didn’t either.

ONE

FOR AS LONG as I can remember I was always thinking how I could make some money.

It goes back as far as primary school. While other kids my age were perhaps playing football or basic video games I was working out ways to get rich – as quickly as possible. It’s not that I didn’t try those other things. I gave playing football a try but fairly soon realised I was rubbish at it. I fleetingly wanted to be a pilot. However, ever since I was nine or ten I wanted to be an entrepreneur.

By the time I hit my teens the financial markets fascinated me. It was 1985 and I was 14 years old. The Big Bang revolution of the London finance industry was still a year away, but I was already planning my own first foray into a world that was opening up. I read up on the emerging traded options market. I realised there was a way that someone without money could make some quick cash.

Back in the pre-Internet eighties, BT operated an unsophisticated online computer service called Prestel – a precursor to the World Wide Web. I was still living at home, but in my room I had a financial markets screen very similar to what Reuters or Bloomberg produce today. I was a bit of an odd child!

Studying the markets, I spotted a trend in the shares of an engineering company called GKN. It was a bull market, so all share prices were rising, but GKN’s were performing particularly well. I called up a stockbroker in Glasgow. It helped that my voice broke early and I sounded much older than I was. I gave my name and address and said I wanted to buy ten call option contracts of GKN for £2000. I knew the broker would send me a contract note and I had 14 days to pay. All I had to do was make sure I closed the contract before the 14 days were up. By the time I sold the shares they were worth £4700. I hadn’t had to part with any money and they sent me a cheque for £2700. At 14, it felt as if I was a millionaire.

Those were the days before the regulation we have now. There was none of the nonsense anti-money laundering rules where you have to send copies of your passport and utility bills to confirm identification. I’m not sure there was even an age restriction. I didn’t care.

What would I have done if it had all gone wrong? I would have been liable for the £2000 call option price. I didn’t let on to my friends what I was doing. I don’t think I even told my parents. I just started saving and continued trading. I didn’t have a plan, other than to one day set up my own business. I might not have known then what I was going to do with my life, but I knew I wanted to be my own boss.

My parents both had their own businesses. My dad ran his company, Tom Whyte Plant Hire, first in Motherwell and then in Glasgow, while my mum Edna had a baby wear shop in the town’s Brandon Street. We lived in North Lodge, considered one of the nicest areas in Motherwell. My younger sister Adelle and I enjoyed a comfortable middle-class upbringing. My parents came from working-class backgrounds but both embraced the freedom that came with being their own boss. They were also laid-back and liberal in their attitudes to life. My sister and I attended the local primary school, Knowetop, but when it came to secondary school we had a say in where we wanted to go. Adelle chose the local state school but, largely because my friends were going there, I chose the private Kelvinside Academy in the west end of Glasgow.

Going there on the train gave me a greater sense of independence and freedom. It made me appreciate there was a wider world outside of Motherwell. It also had a bearing on my football preferences. Some Motherwell supporters might disagree, but many football fans in Lanarkshire have a local team they support and a bigger team they like to do well. It’s especially true when the so-called smaller teams spend time in lower divisions, like Motherwell did in the early eighties. I had affection for Motherwell and used to go to games there with my dad from the age of eight. His company took hospitality at Fir Park and used to entertain some of the guys from Ravenscraig steelworks.

Rangers had always been in the background, but that changed when I started school in Glasgow – it seemed more fun and interesting to go to Ibrox than Fir Park. I bought a season ticket for the Copland Road Stand, the first to be redeveloped when the stadium was modernised. Rangers were not doing particularly well. It was the John Greig era, Aberdeen and Dundee United were challenging for the major honours and making great strides in Europe. The only decent player I can remember was Davie Cooper. There were days when he was worth the ticket price alone. The football might not always have been great, but the atmosphere was good. I was never a fanatical supporter, but I enjoyed going with friends. It wasn’t the most important part of my life, but it was all quite enjoyable.

What wasn’t enjoyable was school. I found Kelvinside uninspiring. My friends and I were pretty rebellious and if we didn’t fancy going to school we would take the train through to Edinburgh and hang about there for the day instead. When I did go to school, I enjoyed economics and English. I had a head for arithmetic and numbers, but zoned out when it came to the more complicated stuff. That was my attitude with most subjects – what use would they be to me in the real world? What subjects did I need to know?

I didn’t always get it right. I remember scoffing that I would never need to speak French and then years later I ended up living in Monaco and had to spend money on lessons.

Kelvinside was a rugby school, which didn’t suit me because I was still interested in football. I was in the worst team, but we used to train on pitches that later would become Rangers’ training ground at Auchenhowie, near Milngavie, East Dunbartonshire.

School annoyed me because even back then I hated regulations and discipline. At Kelvinside we were forced to join the cadets, whether it be the army, navy or air force. I joined the one I thought was the easiest – the navy. I thought it was all bullshit and gave the least effort possible, but every Thursday we were ordered to wear a navy uniform, complete with beret. Eventually I decided I wasn’t doing it any more so I stopped wearing the uniform. The school still had the cane then so it was a bit of a risk to be so blatantly insubordinate, but at first nobody seemed to notice. Then somebody told me off for it and I was made to wear the navy uniform every day as punishment and march up and down the playground every night after school.

This was just before my 16th birthday. I had passed my eight o-grades and it was nearing the end of the term before Christmas. I told my dad I wasn’t going back after the winter break. I wasn’t having this any more. By that stage I had earned around £20,000 on the markets and probably had more money in my bank account than the teachers. My parents made a half-hearted attempt to talk me out of it. My dad made me pay the school fees that he was liable for. It amounted to around £2000, but it was worth it to get away. So, at 15, I left school for good.

At first I went to work for my dad. From an early age I had gone to the yard and washed the JCBs and other construction equipment. Getting to drive the big diggers at 13 was my idea of fun. Latterly I’d been helping out there after school and at weekends, when he paid me a fiver for two days’ work.

When I first went full-time I worked as a hire controller. When people booked their orders to send the machines to the building sites I made sure they were there on time and the drivers knew where to go. I accompanied my dad to the building sites and learned so much there, meeting a whole host of weird and wonderful people. It was great experience. People wanted you to be efficient and they’d give you absolute hell if something went wrong. If equipment broke down, they let you know. If drivers didn’t turn up or people showed up drunk, you had a problem on your hands. It was a baptism of fire, but I embraced it.

Once I had to find a guy who was missing from his shift. When I eventually tracked him down it transpired he had been in a brothel all night. The construction industry in Glasgow was a different world from the rarefied air of the City of London, where I would spend so much of my career, but the grounding I got there stood me in good stead for the challenges ahead.

I was working alongside an older colleague, but within months I became the more senior person. It was a dream scenario for a 16-year-old. I was still trading and I didn’t have to go to school. I had more money than most of my friends, 95 per cent of whom went to university and were broke for the next three or four years.

I bought a motorbike – a pretty rubbish second hand one for a hundred quid – but I never sat my licence. Having driven the JCBs and 35-tonne trucks in the yard, I didn’t feel the need to, and it got me about until I sat my driving test a few days after my 17th birthday. My first car was a secondhand black Ford Capri. With it came an even greater sense of freedom. Although I was working for my dad and trading, I was on the lookout for my next opportunity and, still 17, I set up my first business.

I started a company that rented mobile phones. The handsets back then cost more than £1000 – prohibitively expensive for most would-be users. But the coverage wasn’t too bad and I could see the benefits for people using them on building sites. I gambled that by investing in a few of them I could make the money back by renting them out. I took an advert in The Herald advertising the service and rented them for £75-a-week, which sounds incredible given how cheap they are today, but I was satisfying a demand. In addition to construction firms, I rented them to BBC employees who found them useful for outside broadcasts.

I was spending the majority of my time in Glasgow, so the logical next step was to move out of my parents’ house and into my own flat. I found one above the old fire station on Ingram Street, in the Merchant City, in Glasgow. The area was becoming gentrified, with a host of new builds springing up alongside conversions of older properties. Although I could afford the £500-a-month rent, my friends were students so our hangouts were the student union or places like Bonkers and Carnegie’s. I had a few girlfriends around this time but nothing serious. Compared to my friends, who were mostly skint, I was probably a decent date, if only because I could treat them to meals in nice restaurants. My parents liked to eat out and my dad and I would often go for lunch, so I never felt out of place walking into more high-end establishments, even though I was still relatively young.

Throughout this time I continued to go to Ibrox. By now Graeme Souness had arrived and the transformation was instant. The signing of some top English players – due in large part to the lure of European football at a time when clubs south of the border were banned – was the injection of quality the Scottish game needed. When David Murray took over the club two years later they pushed on even further.

As the eighties drew to a close my dad sold his business to the BET Group, which became part of Rentokil. Initially we were both going to stay with the new owners, but very quickly we could see that wasn’t going to work. First my dad fell out with them and he left. It was clear the company didn’t want me around, so I swiftly followed him out of the door. It was the best thing that could have happened.

I decided to start my own plant hire company. I still had £20,000 to invest and the experience I had by this point meant I had a fully-formed business plan. I walked into the Bank of Scotland, presented my plan and walked out with a £60,000 overdraft. I then contacted several asset finance companies and set up a credit line to the tune of half-a-million pounds to buy the equipment to hire out. It didn’t seem that outlandish at the time, as I’d been three years out of school, but looking back, it was pretty unusual.

I had to set it all up really quickly. It’s not like today when many online businesses can be launched from a laptop. Starting a plant hire company was a serious undertaking. Once I had the funding in place, I found commercial premises by the famous Barras market in Gallowgate, bought £100,000 worth of plant equipment, set up phone lines, found my first customers, employed delivery drivers – everything. Whyte Hire was born. I was creating something out of nothing, but I knew the market well, I knew the equipment to buy and I knew the business. My dad had signed a non-compete agreement during his own buy-out deal so he couldn’t work for me, but he was there if I needed his advice.

It was an exceptionally busy time, but it worked. In our first two years of trading we made a six-figure profit. I bought my first flat, in Lancefield Quay on the waterfront. I swapped the Capri for a Mercedes, then traded that in for a Jaguar XJS, before settling on a Mercedes SL with personalised number plates.

After the Club Deck opened at Ibrox in 1991 – the third tier of the main stand – my company took a box there. We would have a lunch before the game, some champagne and everybody got pissed. We’d bump into some of the players. Paul Gascoigne would come up and have a drink before the game sometimes, which I used to think was a strange thing for a footballer to do, but he was a character and nobody cared. They had a great team back in those days.

Things were looking up, but in our third year various factors conspired against me. The recession of the early nineties bit hard in Scotland. The construction industry is always among the first to feel the squeeze in any downturn and I was sitting with too much plant to hire. Then a major customer reneged on an outstanding bill, leaving me staring into the abyss. I sought help and asked one of the asset finance companies to restructure my debt. They refused. I was running out of options. I took advice from an insolvency practitioner called David Robb. He took me through the process. I set up a new company and put the old one into liquidation. Not one person lost their job. They all came with me to the new company. However, the pain of seeing a company go bust stung me. For a long time I didn’t tell anyone, but in some ways that period defined my whole career. It was eye opening. I saw how things could be done and how ailing businesses could be restructured. The lesson was not to get too attached to one legal entity. You can restructure these things and keep going. That’s what I did with the plant hire company.

Yes there were creditors that didn’t get paid, but equally there were debtors who didn’t pay me. It’s the risk you take if you extend credit to someone. I accept that some people got hurt, but I tried everything to restructure the debt. You can either throw in the towel or look for a solution. If I had walked away from that business, everybody was out of a job. By setting up a new company, I saved those jobs. I believe that was the better way to go, but I can appreciate the criticisms. It was an easy decision to make. I wanted to keep the company going and it was a successful restructuring.

My new company became part of a wider Custom Group, a business services firm. One of the lessons I learned was to diversify into areas that didn’t require such a heavy capital investment. I bought security companies, contracting businesses, cleaning companies, where customers could be found first and the staff hired after. The risk was lower. We did a lot of labour hire when the Royal Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport and the Naval Base at Faslane were being developed. I might not have made it as a cadet, but I could supply something to assist with the nation’s defences. We had hundreds of guys working up there as part of that project. Soon the group was turning over £10 million and I was making £1 million a year.

I acquired businesses in England and started to look further afield, to New York and to Asia, where I travelled to Hong Kong, Thailand and Vietnam. Arriving in Vietnam, I was amazed to see there was next to no foreign investment. This was before the Asian boom and in Hanoi I found a city with over six million people, yet so unsophisticated. I’d arranged to meet a business contact there and, without an appointment, we went straight in to see the government ministers. I didn’t go there with the intention of getting involved in anything in particular. I just went there to look for opportunities, but I ended up buying a factory that manufactured ceiling tiles. I also did a deal to send second-hand construction equipment over there.

I had enjoyed operating under the radar, quietly expanding my little empire, but eventually my activities were bound to get noticed and so it was in 1996, when a writer called Terry Houston approached me. He was compiling a book of Young Scots In Business and felt I was an ideal candidate. He interviewed me about my experience. I didn’t see any harm in it, but a few months later the Sunday Times picked up on it and included me in its Rich List. It was my first taste of how journalists are able to twist facts to suit their own ends. It wouldn’t be my last.

The Daily Record then jumped on the bandwagon and, amusingly, included me in a rundown of Scotland’s most eligible young bachelors. I don’t think they’d be so favourable today. They did me a favour when it came to meeting girls, but I was baffled by the press attention.

After the personal setback of the insolvency, my businesses were doing better than ever and my wealth increased. All I needed was someone to share it with. Although I’d had a few girlfriends, I hadn’t met anyone I felt serious about. That changed when I was 25 and bumped into a girl I had first met as a teenager. Kim Martin worked for her family’s steel business in Coatbridge and I used to see her and her dad when my father and I went out for lunch together. We were nodding acquaintances but got together after meeting in a Glasgow nightclub.

I was involved with a firm of stockbrokers and had met a couple of colourful characters who lived in Monaco. I didn’t like paying tax – I still don’t – and they convinced me the principality was a good place to live. I went down there and they showed me around. There was a lot to like, besides the tax benefits. It was warm and sunny and people seemed to enjoy more freedom there.

I found an apartment on Boulevard D’Italie, overlooking the sea. Kim came with me to Monaco. It was our first place together and it was an exciting time. I still had the Custom Group and commuted back to the UK from there. Before long, we moved to a new place on the seafront on Avenue Princesse Grace, where we had people like Philip Green, Shirley Bassey and Ringo Starr for neighbours.

It was another world out there. It was impossible not to be seduced by the glamorous lifestyle. In our first year there I chartered a yacht for the Grand Prix that May. I went 50-50 with a friend and we had it for a week, but when we turned up we realised it wasn’t the best yacht in the harbour.

For the race, all yachts have to move five metres out from the harbour. We had a lot of friends on board for a party, but the bay was quite choppy that day. Some of our guests were feeling sick and wanted to get off, but they had to stay on board until the race ended.

I did toy with the idea of owning a yacht at one stage, but days like that, and the experiences of other friends who owned pleasure boats and private jets, convinced me it was better to short-lease or buy shares in them. The yachts might look amazing but even if you’re a celebrity there’s very little privacy because of the 30 staff needed to run them. Having said that, I have enjoyed many great days aboard other people’s yachts and was always happy to get an invite.

Kim and I tied the knot in the gulf coast town of Naples in Florida, at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. We had been there on holiday and liked it so much we decided to get married there. We wanted a low-key wedding, with little fuss and it was perfect.

As I looked forward to the new millennium I hoped it would be a time of new opportunities. But my next business setback was waiting around the corner. And the repercussions from it would be devastating.

TWO

IN BUSINESS THERE are always things that go sour and there are always people who try to rip you off. When you acquire companies you hope you can turn them around, but it’s not always possible. Any number of factors can turn against you. I’ve done a lot of turnarounds and by their nature they are messy. You take a firm through the insolvency process and sometimes creditors get left behind.

This was the case with Vital Security, a small Scottish firm I bought for just £120,000 in the nineties and merged into an English company. Although I financed the deal, I didn’t actually run the company. The hope was that it could bring in contracts and improve its turnover, but it didn’t work. The company stopped trading a few years later long before Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) came looking for unpaid VAT amounting to £200,000. The company had no value and was going bust, but I offered to pay the tax debt over a period of time. HMRC turned me down.

The case called at court in 2001. The cost of defending myself would have been £100,000. When I weighed up the consequences, it didn’t seem worth defending. Technically, I was only a shareholder in the company, not a director. The person who was the director did turn up at court and basically laid all the blame at my door. He played the ‘it was all Craig Whyte’s fault’ card long before it became popular. There was an element of truth in what he said, but he made it appear that I was a shadow director, acting behind the scenes, pulling the strings. The court accepted his explanation and I was disqualified as a director in the UK for seven years.

I didn’t see the judgement as that big a deal. Like most government policies, the law on directorships ends up achieving the opposite of what it intended. Banning problem directors doesn’t curb their activities. Anyone with half a brain can get around it, and it means the authorities can’t monitor them.

The judgement was bullshit. It didn’t affect me one iota. I was living in Monaco and by then had sold my business interests in the UK. The disqualification was due to run to 2009, but I shrugged it off and got on with life.

Kim and I were enjoying our time in Monaco. Our first daughter, Tiffany, had arrived in 2001 and life there suited us. It was good to see Rangers play there in the Champions League in 2000, when Dick Advocaat’s side stunned the hosts by taking all three points in a group game. With a blend of foreign and homegrown talent, Rangers looked to have a team that could compete at the very highest level, but success in Europe continued to elude them.

I used to enjoy lavish lunches with a bank contact whose office overlooked the sea. Over one such meal he told me the bank’s richest client lived in Costa Rica, a little-known tax haven which, he said, offered even greater financial freedom than Monaco. This was music to my ears. My view on tax is that transactions between people should be voluntary, and that goes for the government as well. Tax havens are completely moral as they stop governments from stealing your money. Governments are basically shakedown operations, like the mafia, but with better manners. They are parasites with no morals whatsoever. I was doing an increasing amount of business in the States as well as playing the American markets, and being based in Costa Rica would be perfect for the US time zones, as well as the tax situation.

I floated the idea to Kim as an adventure for our young family. She agreed, so I went hunting for a property. The house I bought was being sold by the American inventor of the boxes that keep pizzas warm. He’d sold his business for tens of millions, but renounced his US citizenship because he hated paying exorbitant taxes. I had some affinity with him.

At the same time we had a holiday house in Palm Beach, Florida, and I bought a house called La Tourilliere, near Cannes, in the Cote d’Azur, where ‘Baby Doc’ Jean-Claude Duvalier, ruthless dictator of Haiti, fled after being deposed in an uprising in 1986.

For two years we moved between houses, enjoying the rich variety these exotic locations offered. We celebrated the birth of a second daughter, Honor, in 2004, and relished our luxury nomadic existence.

I wasn’t particularly itching to return to the UK, but two years on from Honor’s birth I spotted an advert in The Herald that aroused my curiosity. Castle Grant, the 15th-Century former seat of Clan Grant, was up for sale. The 70-room house, in Grantown-on-Spey, in the Highlands, had been repossessed from its previous owner and I knew someone acting for the mortgage company. We went to have a look at it and fell in love with the location. It was beautiful, but the house was desperately in need of some tender loving care. It was almost a wreck, hence the distress sale, but that appealed to me. I bought it for £750,000 and it was exciting to be coming home to Scotland.

Once we moved in we realised the castle was completely impractical as a family home. It was the first time it had been used as such since the Second World War. We immediately set to work getting it refurbished, but the workmen were scared to go into the castle after dark. There were rumours it was haunted by several ghosts, including the sad spirit of Lady Barbara Grant, who apparently died of a broken heart after being imprisoned in a dark closet for falling in love with the wrong man. I didn’t see or hear anything remotely spooky, but we heard from some of the workmen that tools had started by themselves. I was surprised by the number of people who were convinced the castle was haunted. We had guests who were sure they had seen and heard things. One of the ghosts was supposed to be a piper who had marched from Inverness to Castle Grant and piped around the building before dropping down dead. My mum came to stay and she was convinced she heard bagpipes in the middle of the night. One chamber in the castle was called the Skull Room and rumour had it the chief of Clan Grant killed the patriarch of the family that originally owned it and left his head there. If that was the case, it wasn’t there when I bought it.

The castle wasn’t the wisest investment I ever made but it was fun living there. Kim gave birth to our son, Lincoln, in 2008 and it felt our family was complete. The girls went to the local school and Kim got involved in the community. I’m sure the locals thought I was some strange guy who was hardly ever there. I had a flat in Belgravia, London, and spent weekdays there before flying up to Scotland for the weekend. My time was now spent acquiring financial services companies and trying to make them work. I bought several stockbrokers and asset management companies under the umbrella of Merchant House Group, of which I owned 30 per cent, and had an office overlooking St Paul’s Cathedral. I was constantly on the lookout for restructuring opportunities. I owned diverse operations, from one that ran the buses in Surrey and Sussex, to construction companies.

By 2009 I had more than a billion pounds under management, status that would one day prompt the Daily Record’s unhelpful headline that this somehow made me a billionaire. There is a world of difference between being cash rich and managing other people’s money.

I was working long hours and trying to juggle my business ventures with the responsibilities of a husband and father with a family up in Scotland. I thought I was pulling off the juggling act – but as far as my wife was concerned, I had failed. We’d always had a traditional relationship. She looked after the family, while I earned the crust. In her eyes though, I had abandoned her up there in our remote castle, while she was trying to deal with two girls and a baby. She wanted a husband and father who was present – and I couldn’t satisfy her demands.

Matters came to a head on Boxing Day, 2009. Our marriage was broken beyond repair. I left the home and moved to London. Perhaps we might have been able to resolve matters had I not had a place to retreat to, but I felt I had no option but to leave. Within three months she took the children and moved out of the castle into a house nearby.

It took eight years to finalise the divorce. We had reached a settlement and after that I took the kids on holiday. While we were away, hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of items were removed from the castle. There is a lot still to be worked out, but I have been painted publicly as the villain. This is something I strongly refute. If I had to live my life again I would pay more attention to my family. However, it seemed impossible for me to spend time with my family and I was caught up in things I thought were exciting. I do regret not being there when the children were growing up, but it seemed impossible at the time.