Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

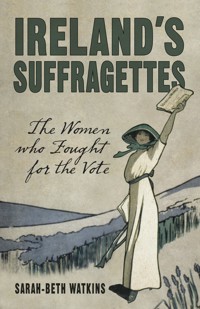

Ireland's Suffragettes is a collection of biographical essays introducing the suffragettes who influenced Ireland's struggle for women's rights. Many of the women were political activists while others became militant suffragettes between 1912 and 1914. The struggle of the suffragettes is different to that of the UK, in that many Irish suffragettes were also included in the struggle for independence and the inclusion of women in the trade unions movement. Drawing on primary sources located in the National Archives and the National Library, Ireland's Suffragettes will bring to life not only the most famous names in the suffragette movement but also the other women who made women's rights their lives work.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 176

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The Militant Suffragettes

Margaret Connery

Margaret Cousins

Kathleen Emerson

Mabel Purser

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

Marguerite Palmer

The Murphy Sisters

Barbara Hoskins

Kathleen Houston

The English Suffragettes

Mary Leigh

Lizzie Baker

Gladys Evans

The Belfast Suffragettes

The Political Suffragettes

Anna Haslam

Louie Bennett

Charlotte Despard

Maude Gonne

Eva Gore-Booth

Mary Hayden

Rosamund Jacob

Delia Larkin

Countess Constance de Markievicz

Somerville and Ross

Isabella Tod

Jennie Wyse Power

Kathleen Lynn

Mary Colum

Marion Duggan

Mary MacSwiney

Susanne Rouviere Day

Helen Chenevix

Dora Mellone

Margaret McCoubrey

Afterword

Notes

Bibliography

Copyright

Abbreviations

DWSA

Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association

ITGWU

Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union

IWF

Irish Women’s Franchise League

IWRL

Irish Women’s Reform League

IWSF

Irish Women’s Suffrage Federation

IWSLGA

Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association

IWSS

Irish Women’s Suffrage Society

IWWU

Irish Women Workers’ Union

MWFL

Munster Women’s Franchise League

NESWS

North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage

WILPF

Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

WSPU

Women’s Social and Political Union

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all those who have helped in my research during the course of writing this book, including the staff of the National Archives and the National Library in Dublin for their kind assistance and the answering of many queries, as well as the staff of the Museum of London and the British Library. In particular, I would like to thank the British Library for permission to quote Kathleen Emerson’s poems from ‘Holloway Jingles’, a Women’s Social and Political Union pamphlet compiled by N.A. John.

I would also like to thank the National Archives of Ireland and its director for kind permission to quote from their archived sources and the National Library of Ireland and the Museum of London for permission to reproduce photographic material.

Many thanks also go to Simon and Jill Muggleton for information on their ancestors, the Murphy/Cadiz sisters, and to Elizabeth Crawford, Sandra McAvoy, Una Lawlor and Elizabeth Kyte for helping to point me in the right direction with my research.

Kind regards also go to Dr Louise Ryan for allowing me permission to reproduce paragraphs from the Irish Citizen newspaper taken from her book, Irish Feminism and the Vote.

Last but not least I would like to thank my family for giving me the space and time to mull over my research and for listening to me when I was ranting on about suffragettes!

Introduction

Ireland’s Suffragettes is a collection of biographical essays on the main suffragettes who influenced Ireland’s struggle for women’s rights. Many of the women were political activists while others became militant suffragettes between 1912 and 1914. Irish suffragettes were imprisoned for their beliefs in Ireland and the UK as well as being involved in movements across the world, like Margaret Cousins who began her campaign for suffrage in Ireland and continued the fight for women’s rights in India.

The suffrage movement in Ireland began in the late 1800s and the first public meeting was held in Dublin in 1870. It was then that women like Anna Haslam and Isabella Tod began to debate what they could do to obtain the vote for the women of Ireland. Up until this time, women had been treated as second-class citizens with barely any rights. They were not allowed to hold public office or vote in parliamentary elections, access to education was limited and they lost the right to own property on marriage, with any assets given to their husbands. Women could be forced to hand over any wages to their husbands and they had no rights where their children were concerned. It was a patriarchal society and it was an unequal world for women. They felt that the time was ripe for change.

The first Irish suffrage organisation, the Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association (DWSA), was established in 1876 and it began a process of women working collectively across Ireland towards their aims. In 1898, women were allowed to sit on Rural and Urban District Councils and Town Commissions, but not on County Councils or Borough Councils. In the following elections, over 100 women were elected to these seats. Women had realised that the route to change was through their involvement in politics and this could only occur through having the right to vote.

Suffrage organisations began to spring up, with women getting together across the country to mobilise for access to greater equality. In 1908, the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL) was founded and 1911 saw the Irish Women’s Suffrage Federation (IWSF) and the Irish Women Workers’ Union (IWWU) established. Between 1912 and 1914, the suffrage movement in Ireland was at its peak. In November 1912, seventy-one members of the Irish Parliamentary Party voted against the Women’s Suffrage Bill and Women’s Suffrage Amendments to the Home Rule Bill. The women were furious and decided, for the first time, that constitutional methods for obtaining the vote were not enough. During this two-year period, all the militant action took place and the movement gained publicity and support. But Ireland was a country in turmoil and the political situation was one that the suffragettes fiercely debated, taking sides and arguing over what their priorities were.

Cumann na mBan was founded in 1914 and the Easter Rising occurred in 1916. These were troubled years in Irish history and many of the suffragettes were caught up in the nationalist cause. The struggle of the suffragettes in Ireland was different in that respect to that of the UK; many Irish suffragettes were also included in the struggle for independence and the inclusion of women in the trade union movement. Loyalties were divided and the dispute and discussion that ensued was often played out in the pages of the Irish Citizen, the suffrage newspaper. Today, this newspaper gives us a true testimony of the facts and opinions of the women involved in the suffrage movement, and lets us examine their relationship to nationalism, the labour movement, and each other.

Extension of Franchise poster. (© National Library of Ireland)

The fight for votes for women in Ireland was not easy. Many people were against women’s suffrage, feeling they had no place in the political environment and that women would complicate matters if they were more involved in the politics of Ireland. Some nationalists agreed women should have the vote, but only if Ireland was a Free State. The Labour movement supported the right to vote but unionists didn’t. This was all complicated by the relationship Ireland had to Britain. For the suffragettes who had often travelled to the UK to attend meetings of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), this was never more apparent than when English suffragettes came to Dublin and acted without their knowledge. Many denounced the women and their attack on Prime Minister Asquith but others supported them, especially when they were force-fed in an Irish prison. In contrast, suffragettes in Ulster welcomed their English counterparts when they wanted to take part in more direct militant action and agreed to the WSPU’s involvement in the North. The suffrage situation in Ireland became extremely complicated, but through it all women worked diligently to obtain the right to vote and what they felt would be a turning point in women’s equality with men.

In 1918, women were allowed to vote for the first time but with conditions. They had to be over 30 and own property or satisfy other qualifications. As we shall see in her biography, Countess de Markievicz was the first woman to be elected to Dail Éireann. The right to vote was finally granted in 1922 when all men and women in the Irish Free State over the age of 21 were allowed to vote, six years before the same right was granted to the women of Britain. For all the complications of the Irish suffrage movement, the women had prevailed.

The Irish Citizen newspaper. (© National Library of Ireland)

The centenary of the last conviction of a suffragette in an Irish court will be in 2014. The suffragette movement was interrupted by the First World War when many of the women became involved in other activities: some supporting the war effort, others working for peace. Militant action ceased and did not continue after the war, although many of the women were still involved in the movement.

Drawing on primary sources, Ireland’s Suffragettes brings to life not only the most famous names in the suffragette movement, but also the other women who made women’s rights their life’s work. The women came from many different backgrounds and each one has a story to tell. For ease of reading, this book is split into two parts: the militant suffragettes and the political ones. The militant suffragettes are the women who were convicted and imprisoned, whilst the political focus on women who used more constitutional methods, but many of the women were both. Some started off hoping that reform would come about by lobbying MPs and gathering public support but when this failed to materialise, the women felt that they had no alternative but to take more direct action to highlight their cause and force politicians to take note. Some of the names will be familiar to you while others, I hope, will be women that you have not heard of before. All of them made voting a possibility for women today.

NB: The terms suffragist and suffragette have been used interchangeably throughout the text. We have come to use the term suffragette to encompass all the women who fought for the right to vote within the suffrage movement but at the time, a suffragette was a radical, militant member of the movement, whereas a suffragist was anyone involved in the fight for the right to vote.

The Militant Suffragettes

Margaret Connery

(1887–?)

Margaret was born in 1887 in Westport, County Mayo and was known as Meg to her friends. Very little is known about her early life but she was one of the most active and militant suffragettes. Meg was living in Dublin at a boarding house on Rathmines Road owned by Sarah Bateman in 1912 at the time when the suffrage movement took a more aggressive approach. She was vice-chairwoman of the IWFL, the most radical of the Irish suffrage groups.

Meg was on the speaker’s platform when Prime Minister Asquith visited Dublin and was subsequently caught up in the disorder that followed where suffragettes were heckled by members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. On the 6 November 1912, Meg was smashing windows at the Custom House on Dublin Quays with Kathleen Emerson. Arrested by Constable McQuaid, they were taken to Store Street police station. In court the next day, the women refused to pay their fine and were detained in Mountjoy Prison on 18 November.

The Daily Express noted that other suffragette action had occurred that night, although no one was arrested or prosecuted for it. Pillar-boxes in Lower Baggot Street, Merrion Square, Clare Street, and around the Pembroke and Ballsbridge districts of Dublin were filled with a corrosive liquid, ink and oil that damaged letters. On each of the pillar boxes, a note was left that read ‘Votes for Women’. Had Meg and Kathleen been active all night or were they aided by other suffragettes?

On her incarceration, Meg immediately wrote to the chairman of the General Prisons Board stating, ‘I have been imprisoned today for refusing to pay fine imposed for breaking Gov glass as a suffragist protest & am being treated as an ordinary criminal. I wish to have the question of prison treatment raised at once’.1

Margaret Cousins, the secretary of the IWFL, wrote to the Lord Lieutenant in Dublin Castle to draw his attention to the women being treated as common criminals, including Meg, pointing out that suffragettes were political prisoners which gave them certain privileges. J.B. Dougherty, writing on behalf of the Lord Lieutenant, did not agree to Margaret’s demands. He replied that ‘imprisonment was not an integral part of the sentence, but would follow necessarily upon failure to pay the damages and fines imposed by the court. Payment would avoid imprisonment, and in those circumstances His Excellency is not empowered to interfere with the course of the Law.’ Both letters were published in TheIrish Times, but by this time the women had been released.

Meg’s prison notes also mention that she had served seven days in Holloway for damage done as a suffragette and she is mentioned in a list published in the Irish Citizen of the Irish suffragettes that had been imprisoned in the UK. She was still fighting for women’s suffrage in January of 1913, when she was arrested for breaking more government windows with Margaret Cousins, Barbara Hoskins and Mabel Purser. This time, Meg was sent to serve out her sentence in Tullamore Prison. Again the women asked to be treated as political prisoners or first-class misdemeanants. This was not granted, but they were still allowed their own clothes, to talk, write and exercise. However, the women would not back down from their request and began a hunger strike on 3 February until they were given more privileges. They began to eat again six days later and were not forcibly fed. Meg was released on 27 February with Margaret Cousins.

In November of 1913, Edward Carson, the Ulster Unionist leader and Andrew Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative Party, were in Dublin to give speeches on the Home Rule situation. As they were leaving the meeting to visit Lord Iveagh, Meg and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington broke through the police cordon and tried to press their pamphlets in his hands. They wanted to protest against the fact that no female delegates were allowed at these closed talks and that Bonar Law had refused to meet with the suffragettes. They were both arrested and charged with obstructing the police.

In 1914, Meg set off to bring the suffrage movement to Longford, Carrick-on-Shannon and Boyle. The north-west of Ireland was long seen as a black hole by the suffragists, with no groups or societies working for the cause. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington accompanied Meg and the tour was successful, bringing new converts into the movement.

In 1918, Meg chaired the conference of Cumann na dTeachtaire, an organisation set up to monitor the political environment in respect of women’s interests and to make sure that women’s issues were brought to the attention of the appropriate politicians. The conference was held to discuss the issue of venereal disease and Regulation 40 D of the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) that aimed to protect soldiers from infection. In reality, this meant that any woman could be arrested and subjected to a medical examination. The suffrage movement was outraged by this attack on women’s rights and fought for the act to be abolished.

Throughout Meg’s involvement in the suffrage movement and her tenure as a member of the IWFL, Meg wrote for the Irish Citizen. She wrote on topics such as ‘Irish Militants, the War and Relief Work’, ‘Women and Labour’ and ‘Morality – Conventional or Otherwise’. In one of her last articles, ‘The New Force in Irish Politics’, published in August 1918, Meg said:

If the new woman voter in Ireland has the courage and independence to set a new standard I believe the men of the new generation would try hard to live up to it. There are some questions of burning interest to women which men, even the best of them, will obstinately refuse to face or to think out, unless and until women compel them to face them … Will Irishwomen set a new standard for their country? Will they pierce through the froth of politics to the eternal verities beneath? Irishwomen have a long-inherited passion for national liberty. They will ring through on that issue. May they be equally true and uncompromising on the deep human issues …2

Margaret Cousins

(1878–1954)

Margaret Cousins was born Margaret Elizabeth Gillespie in 1878 in Boyle, County Roscommon to a Protestant family. Her father, Joseph, worked as a clerk in the courthouse in the town. Margaret spent her early life in Boyle attending its national school but moved to Dublin in 1898 to study music in the Royal Irish Academy. Margaret graduated with a degree in music from the Academy in 1902 and went on to teach music on a part-time basis in Dublin.

Margaret married James Cousins in Sandymount in 1903. James was a poet and critic who frequented Dublin’s literary circle and later co-edited the Irish Citizen. They became friends with some of literatures greatest writers, including W.B. Yeats, James Joyce and George Russell. They were both vegetarians, interested in the temperance movement, anti-vivisection, socialism and later, the theosophical society.

In 1906, Margaret joined the Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association (IWSLGA) but she quickly became unhappy with their pacifist stance. She co-founded the IWFL in 1908 with Hanna Sheehy Skeffington to form a more militant organisation. In James and Margaret’s autobiography she says, ‘Hannah asked us and some other friends to join in working out a scheme for a militant suffrage society suitable to the different political situation of Ireland’.1 The IWFL aimed to use both peaceful and forceful methods to obtain the vote for women on the same grounds as Irish men, yet be non-party and open to all Irish women regardless of their affiliations. Margaret explained in her autobiography:

We were as keen as men on the freedom of Ireland, but we saw the men clamouring for amendments which suited their own interests, and made no recognition of the existence of women as fellow citizens. We women were convinced that anything which improved the status of women would improve, not hinder, the coming of real national self-government.2

The IWFL was modelled on the WSPU and Margaret spent three weeks with them in 1909, learning tactics to use in the suffrage struggle in Ireland. Margaret was then invited to the UK by Mrs Pankhurst to attend the Parliament of Women in Caxton Hall which ended in a mass protest. The 18 November 1910 became known as ‘Black Friday’ when over 300 women, including Margaret, marched on the House of Commons when they found out that Prime Minister Asquith had no intention of giving the vote to women. The women were assaulted by the police, being beaten, punched, kicked and thrown to the ground. This was the first case of documented police abuse against the suffragettes and the press leapt to their defence amidst rumours that the women had also been sexually assaulted.

Black Friday, London, 1910. (© Museum of London)

A few days later, as the protest and militant action continued, Margaret was smashing the windows of Cabinet Ministers’ houses in Downing Street with potatoes and flowerpots for which she was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment in Holloway Jail.

During 1911–1912, Margaret was back at home and she spent the time touring the country, bringing the suffrage message to women across Ireland with several other campaigners. But public speaking didn’t come easy to Margaret and she admitted that she rehearsed ‘in a field behind our house with only an ass for my audience’.3 It was only a matter of time before she was caught up in more militant action as their pleas for suffrage continued to be ignored.

On 28 January 1913, Margaret was one of several women who broke windows at Dublin Castle. She was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment in Tullamore Prison with Margaret Connery, Barbara Hoskins and Mabel Purser, where she went on hunger strike until the women were treated as political prisoners. In a letter to the chairman of the Prison Board, Margaret wrote, ‘I am not a criminal but a political prisoner – my motives were neither criminal nor personal – being wholly associated with the agitation to obtain Votes for Women. I shall fight in every way in my power against being branded a criminal’.4 Although they were not officially recognised as political prisoners, the women were all allowed daily visits, to be able to write letters, to have their own food and were exempted from hard labour. The women stopped their hunger strike on 8 February and Margaret was released on the 27th of the same month. In records pertaining to their incarceration, it is noted that there had been no forcible feeding.

The next day, an article that Margaret had written appeared in the Irish Independent entitled ‘In Tullamore Jail – A Prisoner’s Story’. It detailed life in Tullamore for the prisoners and their experiences. In it, she says:

Dublin Castle. (© National Library of Ireland)

We were fighting for our own personal honour, for the continuance of political treatment for all future reformers who might like ourselves break the law in order to amend the law, and for sex equality in political treatment as in everything else. Our weapons were determination, the power of mind over matter, faith in the victory of Right, and sacrifice of our appetites, and if need be even of our bodies, rather than that Wrong should prevail.

At the end of the article she sounds even more determined to carry on the fight for women’s suffrage: