Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In Iron Man, Lynne Bryan writes movingly and candidly about disability, the vulnerability of the body and mind, and the frailty and strength of our corporeality. She writes insightfully and thought-provokingly about the ways in which women's access to head space and the physical and economic space for creativity can be restricted or blocked – sometimes by the people they love best and who love them best; and, of course, sometimes by themselves.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

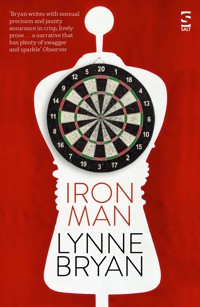

IRON MAN

LYNNE BRYAN

‘… stories may enable us to live, but they also trap us, bring us spectacular pain.’

Red Parts:Autobiography of a Trial

by Maggie Nelson

‘Part of what we fear in suffering – perhaps the part we fear most – is transformation.’

The Return

by Hisham Matar

‘Inescapably, we are beings for whom objects have a spiritual weight.’

Why We Make Things and Why It Matters

by Peter Korn

This book depends on my memory and interpretation of events. The scenes and conversations are not intended to be perfect representations but are evocations of the substance of what happened and what was said.

CONTENTS

HIS WORLD

STORY

There is a story I’ve carried with me since childhood. It isn’t a fairy tale and it isn’t enchanted. It’s more personal than that, and more terrifying. It has the usual story elements: a beginning, a middle and an end. But it’s a reversal of bad turning to good, dark turning to light. It offers no heart-warming redemption, no prince, no pot of gold or honey. There’s a transformation but the transformation is cruel. It is the story of my father’s terrible bad luck.

Once Upon A Time in Fleckney, in the English Midlands, just after the Second World War, my father was washing his hands in the kitchen sink, in the little house he shared with his parents, two sisters and younger brother. He was fifteen years old and a talented cricketer. Leicester County was interested in him. A village lad with real ability. He was washing his hands, thinking about County, when next thing he woke in hospital unable to move any part of his body except for his head. Everything between washing and hospital a blank. He’d caught the infantile paralysis disease, poliomyelitis. Or it had caught him. He was unable to sit, stand, bend, crouch, stretch, leap, hug, hold, draw, write, cross his fingers, do the V sign, thump, grasp, feed himself, go to the loo by himself, put his head in his hands and cry. But slowly the feeling came back. He was able to move his shoulders, to wave his arms. He found he could kick his right leg and flex his right foot. His left leg though … wasted, no strength, done for. He had to wear a calliper on this leg. His cricketing days were over. He had to learn to haul himself around on crutches. He’d become a cripple.

I can’t remember being told this story. It just is. It squats inside me: its brevity ominous and stifling. A story of impotence. Young, innocent, healthy boy felled, ruined forever. No reason why him. A terrifying story about fate, about not knowing what the future has in store. One moment you’re this person with these abilities, the next you’re somebody else entirely.

What does a child do with a story like that? It wasn’t a story I could repeat to my mates; I knew they’d all go running if I tried to share it. I also couldn’t discuss it with my family – with Mum or my sister Mandy or any relative – because this was Dad’s story and he’d shaped it and its tightness told me that it wasn’t to be messed with. There’d be no unpicking, no questions, his word was law.

Sometimes I see Dad’s story as an object, a punctuation mark, a full-stop, one of those monumental full-stops made by the artist Fiona Banner but not as glossy, a dark round thing blocking and ending and finishing off. Lump. I see it as a wall too, concrete and high, surrounding me and my family, keeping us trapped inside and life and everybody else out.

What the bloody hell is that? Dad would say, when we watched Top of the Pops together.

Mum would be taken up with housework in the kitchen, but Mandy and I would be on the sofa, trying not to reveal that we wanted to be one of Pan’s People or we fancied both David Essex and David Bowie, and as for Marc Bolan …

Jesus, is it a girl? Dad would say, sitting in his chair, which nobody else dared sit in, his crutches propped against the wall.

He’d scoff and swear, finding these weird pop creatures so very funny. Then in 1979 Ian Dury and the Blockheads appeared playing ‘Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick’, Dury growling out the lyrics. I was 18, desperate to leave home. And suddenly, explosively, there on the screen, was another man who’d been crippled like my dad. Dury had a gammy leg, he wore a calliper (an iron), his body was twisted. He was the only other physically-disabled person I’d noticed in all my childhood apart from the Spastics Girl outside Boots the Chemist, who wasn’t human but a representation of a human, a plaster model of a young girl wearing a prosthesis like Dad’s and holding a teddy and a collecting box: Please Help Spastics.

I found Dury gorgeous: vital and furious and cheeky and creative. It was love at first sight. This amazing man spat out his funny, jolting, colourful lyrics and our living room contracted. Dad said nothing. I daren’t look at him or my sister. I stared instead at the carpet, which was made up of brown squares within cream squares within brown squares, and I listened, thrilled and ashamed by the energy in Dury’s voice. So there were other men like Dad? Crippled like Dad but not like him too? A polio punk. A cracker’s cripple. I wanted to run away and live with Dury. I wanted to be him. His words were like balls batted out there, one hundred miles an hour. He thwacked his story into the world and he thwacked other stories too. There was no wall. There were The Blockheads but no block. I saw him as fearless and curious. No limitations.

My father worked in the shoe trade as a puller-over and a clicker, and later in engineering as an instrument fitter. Dury worked as an illustrator and art teacher before becoming a lyricist and vocalist. I love art and words too, and so in a way I have run away to live with him. I’ve studied and taught both subjects, and I’ve had books published, and my favourite thing to do is to read. I know the power of story.

Here’s another story: for years now I haven’t had anything published. I’ve been writing and writing but haven’t been able to finish a single narative. There’s a tower of uncompleted manuscripts in my office at home: countless short stories abandoned, five novels unresolved, essays, even a play script. An age thing perhaps, a loss of innocence, self-belief? Or something else entirely?

You should write a bestseller, my father’s fiancée often says to me, that’s what you should do.

No, that’s not what I should do.

I don’t say this to Sandra, but I think it; that’s not what I’m about.

Stuck. Lump. High wall. Trapped.

Fuck it.

Time to face facts. I’m about me and I’m about Dad and I’m about bloody polio and what it did to us. That’s what I should write. The beginning, middle and end of living with disability. The complications, stuff unspoken, the hidden, the denied, the shame and struggle of it. The brutality. The bravery. No condensed full-stop of a narrative but something more elastic. A story about the awful event that changed Dad’s life forever and a story about those futures that came after that event. Futures circumscribed by his bad luck and how he chose to handle it, and by the way society – or, as Dury put it, the normal folk – chose to handle him and others like him.

Because stories – like events – have impacts. Dad knew this; he wasn’t daft.

A BEGINNING

I never have trouble with beginnings. The blank page doesn’t scare me. But perhaps I love beginnings too much. I can never choose: this one or that, which is best? My real-life beginning – if we ignore conception – is my date of birth, 10th May 1961.

I took my first breath in the City Maternity Home, Westcotes Drive, Leicester. Dad wasn’t in the delivery suite with Mum because that was how things were back then; he may even have gone into work that day. The labour was long and bloody. I was born with a nevus all over my back. Mum says the doctor had to stand on her belly to get the placenta out which I find incredible but I can’t quiz Mum about it because we don’t do that kind of thing in our family: we don’t ask questions.

So that’s a beginning but I have no memory of it, same as I have no memory of having my photograph taken propped on my father’s lap in the back garden of his and Mum’s first home. The home was a terraced house in Wigston, Leicester, a few doors down from Mum’s parents’ (although Roy and Dorothy weren’t her real parents but that’s another story entirely); its back garden was really a yard. Looking at the photo now I can see a small lawn divided by a concrete path and a border of bedding plants. The plants are in flower; it’s probably June or July, a couple of months after my birth. Dad’s sitting on a deckchair that is as wide as the path. He resembles a young Tom Jones. His crutches are nowhere to be seen, but part of his calliper is visible, poking out from under the hem of his trousers. He has me propped on his gammy leg, balanced in the crook of his arm. He is showing me off like a trophy. Big smile on his face, looking down at me. Dad was good with the smiles. He laughed a lot too. He had a ready wit, an answer for everything. Beware. Sometimes those answers would rear up at you, snarling.

But I’m stating more than showing. One rule of good story-telling is to show through scenes. Think sounds, sights, smells. Dramatise. Let the reader live the experience. 1969. Let’s begin again. I’m no longer a dumb baby but I’m still a long way from being an adult; I’m conscious of my surroundings and I’m developing some understanding that the world is complicated, and now there is no doubt I have Dad’s story squatting inside me and troubling me too.

I’m in Mum and Dad’s bedroom in the bungalow on Horsewell Lane, then a road on the outskirts of Wigston Magna, a village turning rapidly into a town. I’m allowed in the bedroom because I’m with Dad. He is playing darts.

Mum and Dad moved from their two-up, two-down when my sister was born. That place was impossible to live in because Dad wasn’t able to get up the stairs and so we all scrunched together in the tiny rooms downstairs. My sister was the tipping point. All the noise, no sleep, the danger of tripping over stuff, hot stove, wet nappies, Dad’s crutches and the Restmor pram, bloody chaos. So, Mum’s father Roy (who wasn’t really her father) built this bungalow for us. My sister and I will live in it for most of our formative years. A simple design of five rooms, including the bathroom, and an L-shaped hall. My sister and I share a bedroom at the back; our parents’ bedroom is at the front. Their view is of the front garden, which is full of shingle and one large leylandii and, beyond, the estate: rows and rows of yellow-brick council houses. From my position on their bed I can see the road opposite, just past the fronds of the tree, which is named after the famous highwayman George Davenport who, like Robin Hood, robbed the rich to feed the poor.

Bugger, says my dad. Get that for us, would you?

I clamber from the bed to pick up the dart that’s pinged off the board. This is one of my jobs today. It’s by Dad’s feet.

My friend Beverly can only see roofs from her bedroom: roofs and chimneys and fire smoke. She says she hates climbing stairs to get to her room; it’s exhausting. But I find stairs exciting. They go up. They lead away from things. You can run up them and hide.

Things to hide from: Mandy, because she’s annoying and fidgety and a pain; Mum when she’s ratty; Dad when he bosses me and when he’s ratty and angry too; Mum when she sews Mandy and me matching clothes to make us look like twins; my Clarks sandals with the toes cut out of them so my toes can breathe; Dad’s potty smell coming up from under this bed; Dad’s arrows when they ping off the board and try to stab me.

I give the arrow to Dad.

Right, ok, here goes, he says. Let’s get it right this time.

He squints at the dartboard and that’s my cue to run back round to Mum’s side of the bed, the safe side. I clamber up, grabbing the pillow to hide behind, Mum’s hairspray stink in my nose. The pillow’s my shield; it’s not metal, like a Roman shield, but it’ll do the job if an arrow hits the wire and pings off and whizzes at my eyeball. Pillow up, eyeball saved, that’s what Dad says. Eyeballs are important to save, and your other bits too. I know this. You have to keep your arms and legs and eyeballs and things working because when they don’t work it is Hell on Earth, a real fucking bugger.

Swearing: Dad and Mum can swear out loud, but Mandy and I can only swear in our heads or in secret, in whispery voices in our bedroom. Sometimes Mandy and me swear at each other and hit each other in our bedroom at night. I’m good at digging my nails in her and making curves that bleed. I’m older than her; she is an annoying little shit. She’s not here at the moment; she’s in the back garden with Mum. I’m helping Dad; I’m being his ball boy even though I’m not a boy and this isn’t Wimbledon, but I am doing the same thing, picking up and giving back. I am good at this; I do it a lot. I have to because Dad can’t pick up; he’d fall over because of his gammy leg.

Bam! The arrow hits the board, shivers, stays put. It’s near the other two, in a red bit. It’s good to get arrows in the red and green bits because you score more points. Dad adds up his points. Then he swings to the board, which hangs on the door. The door has some tiny holes in it because sometimes Dad arrows it, because sometimes life’s like that when your arms are too tired from your crutches and work. Dad pulls the arrows out of the board before swinging to his spot by Mum’s dressing table, getting ready to throw again.

Dad’s practising because he has a match at The Liberal Club tonight. He’s captain of the team. He’s won cups and medals and sometimes I polish them with Brasso and a duster. The cups are on the fireplace near the telly. There’s stuff written on them in posh curly letters scratched into the metal by a man in a jewellery shop. Sometimes the letters say his name: Donald Bryan. Sometimes they say a date. Sometimes they say what kind of cup it is: First Prize, Second Prize, Runner-Up.

Sport is Dad’s favourite thing, and numbers, and drinking beer as well. He’s different to me because I like thinking and reading and words. Church is ok too, sometimes, and the Dozen Club. I like school best because I’m a brain-box and a good girl. Mr Lee, my headmaster, says this is the perfect way to be. Me and Philip Dewhurst are his clever ones. We gave flowers to the Mayor of Oadby and Wigston; we were chosen for that. Philip Dewhurst has a huge head and floppy black hair, but he’s snooty because his dad’s normal and doesn’t work in a factory. Dad used to be a puller-over and is now a clicker. These words make noises in my head. Clicker. Clicker. Click. Click. Clicker.

Look at that, double-top, says Dad, his voice doing a jump.

Double-top, I say, trying out these words.

Click. Click. Double-top.

Double-top is a high score, gold stars. I know this, but I’m clicking inside and clicking is more interesting.

Two times twenty, Dad says, which makes?

I’m not sure. Two times twenty. I have to do this. I count on my fingers, behind the pillow. Two times twenty. Sometimes Dad’s voice barks. Sometimes, if something doesn’t happen quickly enough for him. Click. Two times twenty. Seventeen. Nineteen. Bugger. Click. Start again. Two and two then add nothing. Four then add …

Forty, he says, hurling the next dart.

Thud. The arrow stabs the board in the black bit, which is under the red bit, which is where the other arrow is.

Christ, says Dad, flat twenty.

He throws the final dart. Thud.

Better, he says.

I clap my hands, but not loudly. Another double-top. That’s good. I open my mouth to tell Dad that I know it’s good but nothing comes out, just breathing. This happens because I’m shy, that’s what Mum and Dad say; I’m the quiet one. I don’t want to be quiet. I don’t think I am really. My head inside is full of words and sounds.

One hundred, Dad says.

He has added up the lot. Click.

Darts: Dad says darts looks simple but it’s not. Darts is a man’s game. It’s a game of skill. If you want to be captain of the darts team then you have to practise hard and know your maths. There’s a lot of adding up and taking away. I’m not sure if there are percentages too. So darts is about that and then you have to have a steady arm and good balance and excellent eyesight, and you have to have arrows. Dad’s arrows are kept in the wardrobe. He sometimes lets me look. There are six boxes and every box has three arrows inside. An arrow is like a metal finger, which has to weigh just right, that’s what Dad says. Every finger has a flat end and a pointy end. The pointy end stabs the dartboard and has to be sharp to stick right in, as sharp as the needles that stitch up the shoes in Dad’s factory, that sharp. Then the flights, that’s their proper name, fix in the flat end. The flights are feathery and can’t be broken or snapped or ruffled up. Dad’s are white, but he has some posher ones for matches that are red, white and blue like the Union Jack.

Dad pulls the darts out of the board and moves back into position. I’m tired and think I need some air. Mum and Mandy are getting air. Mum says it’s important and that when I was very little she’d leave me outside in the pram in the yard at the old house. She’d do that even if it was snowing. Dad likes the outside too but only when it’s sunny because then he can take his shirt off. Can I ask to go in the garden to be with Mum and Mandy? Would Dad mind? He wouldn’t have anybody to pick up his darts, that’s the problem. I open my mouth, close my mouth, can’t ask.

I will never be able to ask. Fast forward to the middle-aged me and I’m not so quiet but I still struggle to be direct, to make a request or, worse, a demand. I have the words, I am full of words, but they spill from my brain, down my arm, avoiding my mouth, into my fingers and onto the screen and page. The journey is longer and during it the spillage is distilled. I consider tone and rhythm and sense; I lose myself in the fiddling.

Clicker and puller-over. In 1969, when I am eight years old, I am attracted to these words. I don’t know what they mean but I enjoy them for their energy and oddness. I say these words to my friend Beverly and feel like I’m handing her jewels. I don’t understand that their difference is due to them being a lexicon within a lexicon, a language of specialism, the language of the shoe trade.

Another lexicon, the language of darts: arrows, double-top, double-bull, feathers, flights, high ton, Irish ton, iron man, upstairs, downstairs, leg, leg shot, one hundred and eighty, Robin Hood, round the clock, shaft, sticks, three in a bed, ton, ton 80, wire.

And yet another, used by members of my close and extended family, the language of Dad’s disability: crutches, sticks, polio, poliomyelitis, iron, calliper, leg iron, leg brace, knee brace, invalid, crippled, jalopy, paralysed, gammy leg, bad leg, dead weight, discrimination, rehabilitation, allowance.

I know this language belongs more to the adult world, to my father, than the language of darts or the shoe trade even, and so I don’t dare speak it. The lexicon crouches darkly inside me, along with the story of Dad’s terrible bad luck.

But:

Sticks: dogs like to play with sticks.

Iron: Mum does this when watching Coronation Street.

Leg: I have one right and one left, and I have a scab on the knee of the right and I’ve drawn a ladybird on the calf of my left.

These little words bridge specialisms and belong to everyday language too. They’re like the flights, like feathers, their fluttery mutability a relief. They are clever and graceful. Sticks. Iron. Leg. They are like water. I can swim around in them. I can swim and swim and not clonk my head on the sides of the pool because there are no sides. They are freedom, a way out.

I look at my drawing of the ladybird on my leg. I am wearing shorts today, but I am not a boy. Thud. Thud. Dad’s arrows hit the board.

Sometimes I draw myself as a boy and I draw Dad standing next to me. There is a football and Dad doesn’t have his crutches. But he still looks like Dad. He has black curly hair, which ripples like waves. He has big ears and a big nose and he’s wearing the jumper Mum knitted him. It’s brown with Fair Isle round the neck. I’ll take this jumper with me when I eventually leave home for college because it’s made of strong wool and will last for years, but I don’t know this yet. Dad is wearing the jumper now and he’s wearing trousers that aren’t as nice and his shoes are black lace-ups. He’s one kind of Dad at the top and another at the bottom. Top is dressing-up and the bottom is boring. Dad’s trousers have to be wide (but not too wide), so they can go over his calliper, his iron, which is like a cage round his left leg. His iron has to be fixed to his left shoe, which means he can never change his shoes for flip-flops or fancy slip-ons or wellingtons even.

Left. Right. Click. Click.

Dad is in his iron most of the time. He’s in it when he walks round home and when he goes to work or The Liberal Club and when he’s sawing-up wood on the coal bunker in our garden, when he visits the rellies or the bookies or Mouldens the newsagents, in fact for nearly every bloody thing. He doesn’t go to sleep in it though. Then it lies under the bed next to his potty. But I don’t look because that would be rude; I’d get told off and the potty smell would poison me. His iron is like the one that the Spastics Girl wears; I’m thinking this because sometimes people call him Spaz.

Final throw, he says, then we’ll have a cup of tea.

Dad swings back to his invisible line by Mum’s dressing table. The invisible line is what he has to stand behind before he can throw. He fiddles with his bad leg, checking his iron won’t let him down. He needs to be steady. He balances on his crutches, his sticks. I like his sticks; they’re ok. I hold them when Dad goes up and down steps. They’re taller than me and are made of wood and at the bottom they have rubber bits like little rubber boots. Dad sort of hangs himself over his crutches, making his shoulders bunch up. He can’t do anything about this; it is how it is.

Final throw, then Dad will have a cup of tea and I can go on the swing in the garden, if Mum will let me, if Mandy’s not hogging it.

Dad leans forward on his good leg and his right crutch. His bad leg stays put as he tries to sort himself out. He takes an arrow from the three that he holds in his left hand. Left, right. Right, left. Click. Click. He lifts the arrow, straightening his right arm. Click. He squints. Then he throws. Thud.

You little bugger! he shouts. Bulls-eye!

THRESHOLDS

2007, and I am no longer a child – at least not in appearance – and I’m back in Dad’s village where he was born and caught polio and became a cripple, and where he returned to live after Mum ended their marriage. His home, here in Fleckney, is another bungalow, not as simply designed as the one on Horsewell Lane, a bit of a mash-up really. He shares it with Sandra, whom he met at the British Polio Fellowship. I’m visiting with my daughter Rose.

We visit two or three times a year for two or three days, sleeping over in the spare room, which is hung with pictures of Sandra’s family and stuffed with pine chests of drawers. Our visits usually follow a pattern of watching television, going out for a meal at Table Table, looking at the shops in nearby Market Harborough, chatting, doing a bit of weeding in the garden and taking a couple of walks (Rose and I take the walks, just to escape; we feed the ducks on the village pond and sometimes pay our respects to Dad’s parents, who are buried in the churchyard). This visit is different because I’ve dared to ask Dad if he’d like to get involved in an assignment for my postgraduate course at Norwich Art School; Dad’s agreed and has just told me to go into his bedroom because what I want is on the bed waiting for me.

Thank you, I say, as I pick up my camera, trying to hold my nerve.

Fancy thing, says Dad.

It’s got lots of buttons, I say.

Off you go now, he says.

I nod, feeling the camera’s weight in my hand. It’s new and expensive and I haven’t had much chance to use it and perhaps I should take a few practice snaps in this room first. But I’m too self-conscious and the scene too familiar. This room is the largest in the bungalow and serves as living room, dining room and hall. Like the spare room it’s stuffed with furniture, but the furniture is pushed close to the walls so there are clear areas of carpet for Dad to walk along, with no obstacles or trip hazards. The furniture is more utilitarian than stylish: a small table for eating at, wooden dining chairs (three), a small bookcase, a standard lamp and hostess trolley; Dad in his rise-and-recline facing the television; Sandra sitting next to him, also in a rise-and-recline but less elaborate; the television, not enormous but always on; then the easy chairs (two), my Rose curled in the one nearest the picture window.

Rose watches the telly, her eyes sometimes drifting to look at passers-by plodding down the hill to the village shops. As usual she’s longing for this visit to be over so she can get back to her mates, and I want it to be over for darker reasons, to do with Dad and the subtext that thrums through this visit and every one we make, which pulsed through my childhood. I hear it now in the voice of a sprite:

You will never suffer as I have suffered and continue to suffer. I nearly died. I am crippled. I have been picked on for being crippled. I have had to fight for every bloody thing. I am still having to fight. I have polio.

Polio. Polio. Polio.

In most families this word will never be spoken; many are ignorant of this horrible little word. Polio? Don’t you mean Polo, the mint with the hole? No polio.

I need to shrug it off.

I can’t shrug it off, says the sprite. I have polio, and now late-effects polio, no strength in my arms, muscle weakness, fatigue.

I know. I’m sorry.

The bitter sprite: Sorry doesn’t help.

I smile brightly. I do this a lot. It’s nerves and wanting the world to be light not dark. I won’t be long, I say to Dad and Sandra, Rose and the sprite.

I enter the other half of the bungalow: to my right the door to the bathroom, straight ahead the door to the corridor that eventually takes you to the spare room, to my left the door to Dad and Sandra’s bedroom. I turn to face this door. I’m about to enter the most private of spaces. I work the handle and see the metal strip marking the threshold. A scuffed chrome boundary. I step across it. Breathe. I sense the sprite return.

My assignment is for a module called Site, Body, Text and it seemed natural for me to focus on Dad, because his body – its workings, not-workings – has loomed so large. But now I have to ask myself if I’m completely off my rocker. Sandra and Dad are in control of the conversation about his disability, as were Mum and Dad when my sister and I were young. This conversation centres on his state of well-being, what he can and can’t do, what he needs, what he’s being prevented from doing etc. My sister and I are required to soak it all up and to sympathise and not ask to be part of the conversation too.

I should step away, I should close the door quick and put an end to what I’ve started. Instead I switch on the camera, fiddle with its dials and buttons, and look through the lens into the room. Tidy like the rest of the bungalow, its furnishings as modest, brown the predominant colour. I see this before I allow myself to see the bed and Dad’s iron lying on top of it. The bedspread and blankets have been pulled back and the iron is lying on the impossibly-white bottom sheet. I feel sick: Dad’s iron, his calliper, his prosthesis, the thing that helps him to sit and stand and walk. It isn’t as pristine as the sheet; it is grimy with fingerprints and patched with tape. I’ve seen – glimpsed really – the iron before, but not that often, and I don’t think I’ve been alone with it, ever. It describes a leg and a life.

I take wide-angled shots from one side of the bed and the other. I zoom in on the iron’s many components, its architecture, its wear and tear, the metal rods which extend from a lady-like shoe to the wadded section that surrounds the thigh, the straps and buckles and eyelets and laces, the leather pad that protects and stabilises the knee joint. I dare not touch it, not even with a fingertip. Safer seeing it through the lens. I think of the books I’ve been reading recently. Kristeva: getting back to the language of stuff, the abject. Freud too: the uncanny.

The sprite pipes up: Welcome to my home, welcome to polio.

And I lurch from the room.

Got what you needed? says Dad.

I plonk myself at the table again. Too embarrassed to look at my father, to ask how he’s managing to sit without his iron on (has he a spare?), hot, flushing, I stare at the camera screen and click through the images I’ve just taken. What will I do with them? I haven’t a clue.

What’s this about? Dad says. I can’t get my head round it.

I won’t be a minute, I say. I need some tea. Anybody want tea?

Yes, I’ll have a cup, says Sandra.

The view from the kitchen window reminds me of the view from Mum and Dad’s bedroom on Horsewell Lane: wide concrete road, yellow-brick houses opposite, square shapes, shingle, a dob of greenery here and there, and the occasional gnome and wishing well. Sometimes I’ll see my cousin Steven and I’ll duck, hoping he won’t spot me. He’s my father’s nephew and lives with Auntie Rita a few doors up. Dad has no patience with him because ‘he’s not all there’. Dad doesn’t tolerate fools: there is disability and there is disability.

The kettle bubbles as I take the mugs from the wall cabinet. An owl mug for Sandra, a World’s Best Dad mug for Dad.

Rose, I shout, do you want a drink?

I curl in the easy chair next to my daughter. She mouths something at me but I can’t read her lips. Besides, I’m distracted. Dad’s Army burbles in the background, but that isn’t it. It’s my father, his face expectant, waiting for me to explain this art business: why photograph his calliper? I sip my tea and begin, not at all sure myself now, hearing the apology in my voice. So I’m at Norwich Art School, taking a qualification that is similar to my creative writing qualification, an MA. I’ve got a grant that’ll cover fees and some living expenses; I’ve been very lucky and my plan is to use the time and the facilities to combine images with words, so I’ve created this character called Evadne Walker, who is an artist, and eventually I want to write a novel about her and run a show alongside, in a gallery somewhere, which will display works by her, which I’ll have made.

So there’s two types of fictions going on, I say.

Dad looks bewildered.

Sorry, I say, it’s a bit complicated.

I then add to the complication by telling him that I haven’t started my Evadne Walker project yet because I have to complete three modules first: Investigative Practices, Tradition and Reinvention, and the one I’m currently doing, which the photos are for: Site, Body, Text. I stop. The room falls into silence. I feel myself blushing and look to Rose, but she’s pulling at a thread on her jumper; she won’t save me. I look at Sandra. We exchange a smile before she decides to offer me her usual careers advice. It’s meant kindly, but it’s not what I need.

I don’t think a bestseller’s in me, I bristle.

Oh, she says.

I’m just not that type of writer, Sandra. Besides, at the moment, I’m going round in circles. I’m hoping that by coming at writing this way, sort of sideways, it’ll change things for me.

Dad clears his throat and the sprite’s voice comes out: Is your artist woman disabled? Does she have polio?

Sorry, says Rose, suddenly lurching out of her chair, I’ve got a really bad migraine. I need to lie down.

We watch her go. It takes me all my strength not to follow her.

Polio. Polio. Polio.

I want a sprite face-off. I want to rattle my writer’s-block sprite at the polio sprite. I want my sprite to drown the other one out. I want it to bellow that for the past six years I’ve produced so many bloody words, yet I can’t get the words to join together to make a book. Story is evading me. Why? Andrew’s read through my drafts, but it’s got to the point where I’m too ashamed to show him any more. I’m stuck and he’s flying – my husband, the author, the academic, the soon-to-be Professor. It’s our elephant in the room.

Dad chuckles at something on the telly; still Dad’s Army. I hear Lance Corporal Jones pestering Captain Mainwaring for ‘permission to speak’.

I open my mouth but only the good girl is in there. It’s just exam stress, the good girl says. She’s revising too much.

She has been quiet, observes Sandra, but then Rose isn’t a loud person, is she?

Sandra nods at the mugs on the hostess trolley: More tea, Don?

He shakes his head, fixes his eyes on me. What about a brace, for your course, Lynne? he says. I’ve got one I don’t need. It’s leather. It’s new. It fastens with Velcro.

Oh yes, says Sandra.

I can’t be doing with it, he says.

He prefers buckle fastenings, says Sandra.

Oh, I say, well …

It’s just a knee brace, he says. I won’t miss it.

I’ll get it, says Sandra, easing herself up.

It might help you, Dad says.

Sandra comes back from their bedroom with a tissue-paper package. She hands it to me and I lay it on my lap.

Unwrap it, Dad says.

I do as I’m told. The brace is shiny and small, the size of a paperback. I cover it over again. It hasn’t the power of his iron: it isn’t worn and doesn’t speak of his years of suffering. But even so, the sprite’s in it and I worry about taking it home. But I can’t refuse it, that would be insensitive.

Thank you, I say, I’ll just put it in my bag. I don’t want to forget it.

I scurry down the dark heart of the bungalow to the spare room. Rose is on the pull-out, flicking through a magazine.

He’s given me a knee brace, I say.

Oh, she says.

I think he’s enjoying this, I say, the attention. God, do you want to take a walk soon? Let’s get out of here. The air might help your head.

Rose and I sit side by side in the waiting room, watching the clock, wondering when it’ll be her turn to see the doctor because all the appointments are running late. It’s been a fortnight since we were at Dad’s and I’m agitated because I’ve hardly managed to get any coursework done. I’ve been teaching and I’ve been worrying. Rose’s migraines have got worse and she’s spending more time in bed, unable to get up in the mornings. She’s had to stay off school for a few days and now we need to get a sick note from the doctor so she can stay off for longer. I don’t think it’s a bug. She had stomach migraines when she was little, but it seems they have shifted to her head. Why? And is there anything we can do apart from stuffing her full of pills that only work for a couple of hours at most?

The buzzer sounds from Doctor C’s room and Rose’s name is called out.

So I’m coming with you? I ask her. That’s what you want?

Rose nods and we make our way over, not knowing that this will be the first of countless visits that we will make to this surgery and to other medical centres and hospitals, National Health and private, up and down the country, for weeks, months, years afterwards. Nearly a decade of trying to make Rose well again.

Come in, says Doctor C, inviting us to sit, as we cross from one way of being to another.

Rose chooses the chair nearest Doctor C’s desk with its big computer and mounds of paperwork. I ease into the chair neighbouring the weighing scales and the examination bed. I’m familiar with this consulting room and doctor, a kind woman with a fine-boned face and efficient bob. I’ve sobbed in front of her about my writer’s block and she’s organised counselling for me, and I see her every January for what we call my MOT, when she checks my blood pressure and we discuss whether it’s the right time for me to bin my hormone patches. She’s a thorough doctor and I trust her.

Well, she says, after a quick smile in my direction, Rose, hello. Now, what is the matter? Why have you come to see me today?

Erm, Rose stares at her hands. I’m getting really bad headaches, and I feel really tired. My arms ache too, and my legs feel really heavy.

Doctor C types notes into her computer. And how long has this been going on? she asks.

Rose looks at me.

It’s hard to say, I tell Doctor C. Rose has always had at least one headache a week, but these are much stronger and they’re knocking her out. They’ve been bothering her for the past month. Would you say that, Rose? A month?

Yes, Rose says.

Ok, says Doctor C, that doesn’t sound very pleasant.

She shouldn’t really be taking time off school but she just isn’t fit enough, I say. We need a sick note for the school …

Yes, I understand, says Doctor C. I can write you one and I’ll do a few small tests too.

She reaches for the blood pressure machine.

Rose, can you roll up your sleeve? You may have to take your coat off first.

While Rose struggles out of her jacket, Doctor C tell us that she’ll also refer Rose to a children’s specialist at the hospital. I don’t think there’s anything to worry about, she says, but it’s best to be on the safe side.

When we get home I make Rose a hot-water bottle and she curls up in bed and I retreat to my sewing room next-door with a cup of tea. I give myself a moment to look through the window set high in the wall. I watch the sky, the scudding clouds, the gulls wheeling. It feels better now I’ve shifted some of the responsibility for Rose onto a professional. A breathing space has opened up, which I’m going to use for my work.

The official focus of my course is textiles and there’s a lexicon particular to this subject that my lecturers constantly use. Their favourite words are: warp, weft, making, the material, stitch, knit, construct, deconstruct, body, representation, memory, tradition, boundaries, transformation, transitions, domestic, industrial, digital, scopic, haptic, tactile. The camera and the brace are on the table next to my box full of threads. Today I need the tactile, to lose myself in the material, and so I pick up the brace. I listen: the sprite is asleep.

Such a small, light package. I unfold the tissue-wrapping. I turn the brace over, flip it onto its back, its front. I’m able to be fascinated by it now that I’m away from Dad. I unpeel the leather straps. They’re narrow, long, and are for winding around the calliper’s metal rods and the back of the knee. There are four of them and they lead off – two on each side – from the square of hard, brown leather that goes over the knee. In the centre of the square is a circle of softer, lighter coloured leather, which is where the knee comes into contact with the brace when the joint is bent, not straight. The brace is a practical object; there’s no finesse to it. The Velcro fastenings are the only sign that it’s post-Second World War.

I lay the brace on the table, spreading out the straps. It resembles a creature, something scampering, a crustacean. It’s easier to think of it as something other than what it is.

I reach for my drawing pad and sketch it, using ink and watercolours, enjoying a process that is new to me. I imagine the brace with eyes and a tail. Later I sketch it plainly and add words next to these sketches: front detail – folded, back detail – folded. I even start writing what I know of my father’s history, the first time I’ve ever tried to do this: My father was afflicted (cursed) with polio when he turned fifteen. He remembers washing himself at the kitchen sink and then collapsing. He woke up in the hospital numb from the neck down …

His story.

WRITING

I know exactly when I became interested in writing stories. My penultimate year in Junior School.

First day of the new term, and I’m wearing a dress Mum’s made, and I’m wearing socks and my sandals with the toes cut out of them, and a cardigan Mum has knitted. I have my kit bag containing my plimsolls and big navy knickers for games and perhaps another homemade bag containing a pencil case. No dinner money in my pocket because school meals – my favourite beef cobbler followed by spotted dick – are free.

The whistle has blown and we line up to go into our classrooms. Mine is just across from the loos, and its green door is open, ready for us to go inside. Beverly has moved to the school on the estate so I try to make friends with the girl in front of me. She has long hair tied into a ponytail and she keeps glancing round.

I’m Lynne, I tell her, Lynne Bryan.

I’m Jenny, she says.

That’s my mum’s name, I tell her.

Is it? she says.

Later she will become my best friend, but I don’t know this yet. All I know is that I am full of worry and need a wee. I worry that I won’t ever have anybody to play with. I worry that my new teacher will just be like my old teacher, Miss Allsop, who rapped me on the knuckles because I didn’t have a ruler to show at inspection time. Miss Allsop wouldn’t listen when I told her the truth that Philip Dewhurst had nicked my ruler because he’d broken his by slapping it over his knees.

Nicked? she said. Stolen. Stolen is the correct word.

I wonder if I can have a wee. Nobody is watching and I think, if I hurry, I can get to the loos and back in time. I step from the crocodile that’s making its way to the class but Mr Lee is there stopping me.

Oh, I say.

He’s the headmaster, and I’m one of his clever ones.

Hello, Linnet, he says.

He calls me Linnet because it sounds like Lynne and because a linnet is a pretty songbird. I’m like a little bird; this is what Mr Lee says when I’m in his office and he’s looking through my workbooks with me. He sits in his chair behind his desk and I stand next to his chair and he’s big in his big grey suit and he tells me not to be scared and to come closer. Come closer, Linnet. Sometimes he gives me a hug and sometimes he pats and strokes my bum and I like it because it means I am one of his favourites.

Linnet? says Mr Lee.

Yes, I say.

Did you have a good summer? he asks.

Mmm, I say, hanging my head because I can be shy.

Excellent, he says. I look forward to hearing more later.

Mr Lee moves away, and I fret about getting to the loo without him seeing and I manage to do it but don’t really know how. The loo walls have been painted, all the scratches and scribbles have gone, and I can smell the paint as I wee into the pan. I wipe myself. I pull up my pants, then pull them down again and do an extra wee to be sure. Up. Down. Click. Click. I catch the end of the crocodile as it marches through the green door.

Oh, I say.

My new teacher is tall and it’s a miracle because he’s a man but not old like Mr Lee, and not big and fat either.

Hello, he says to me, and you are?

He has the register in his hand.

Let me guess, he says. I’ve only a couple of names left. One a boy and the other, well, it must be you. Lynne Bryan?

I nod.

Take a seat, Lynne, he says.

It is noisy. Everybody’s excited. The tables and chairs aren’t in lines but in groups. We can sit where we want, but nobody can decide and we are all going from one table to the next. I find Jenny and ask her if I can sit next to her. And she says yes!

Right, not so loud, says the new teacher. Settle down, please.

He’s a nice teacher, I whisper to Jenny, and she nods.

He’s nice and he’s a gentleman. Most of our teachers are ladies and they’re crabby and look like grandmas. But our new teacher has black curly hair like my dad and he’s wearing a checked shirt and a green tie; I love green and I love ties. And he has legs that work and he’s standing tall. I love my new teacher. He’s called Mr Davies.

Hush, Mr Davies says. Hush.

He pushes his hands down through the air as if he is pushing the noise back down into us.

Hush, he says. Quiet.

I am good at quiet, that’s what Mum and Dad say, but my sister isn’t. We’re not the same because she’s all mouth and she’s sporty, but Mum dresses us the same.

Do you have a sister? I ask Jenny.

Shush, she says.

Mr Davies asks a boy called Frank to hand out the exercise books. I like these books as much as I like Mr Davies. They have grey covers and blue lines inside for writing on.

Right, says Mr Davies, moving to the blackboard and taking a pack of chalk from the little shelf. Can you put your name on the front of the book, please.

He flips open the pack, and I write my name and watch him. He takes out a long piece of white chalk and he writes on the board. He writes in capitals. He writes his name and he writes COMPOSITION.

I want you to write this word under your name. Now, do we know what this word means?

He runs his chalk under the long word.

Composition, he says, before spelling it out loud. It means making things up. So, this book will be for writing that is made-up. It’s a book for your stories. We are going to work hard at writing stories and later we will print some of them in a magazine, which you’ll be able to give to your parents.

I look at Jenny and she looks at me and there’s a boy next to Jenny who looks at both of us and we are excited.

Like Bunty, I whisper.

Or Judy, says Jenny.

Yes, I say.

Quieten down, says Mr Davies. Now, let’s look at the clock. Ok, we have plenty of time. So, let’s think for a few minutes. Think about your summer holiday. What did you do? Did you go away somewhere? The seaside, perhaps? Or to a museum? Or to the pictures? Did you stay at home and play football or cycle or read books or draw, or did you go train-spotting or fishing or swimming? Think about what you did and get a picture in your head …

We went to Jersey in the Channel Islands. It’s underneath England, over the sea. Mum’s fed up with Butlins and said we can go anywhere now we’ve got a car. Our car is a Ford Cortina and it’s silvery blue. We had to take it because of our suitcases and because Dad can’t walk very far. Dad used to have a jalopy, but that only had one wheel at the front and one seat and it wasn’t good for anybody else but him. Dad called it a jalopy because its real name is a mouthful: invalid carriage. Dad is an invalid and carriage is like what horses pulled in the old days. But that’s not my holiday. I have to think about my holiday. We went on the ferry, which was puffing out black smoke and some of the smoke fell in Mum’s hair and on her dress and burnt her. Then we got off the ferry and the car was put on a crane and the crane lifted the car out of the ferry and onto the road. Then Mum had to use her map and we went to St Helier, the capital city. Dad got cross because we went the wrong way, but then we found the B&B. B&B means Bed and Breakfast. It was a bungalow B&B because Dad can’t climb stairs and it was called Brooklands and the owner was Louis who has big hair like a lady and had a friend helping him called Kevin. Dad says they are poofters. I’m not sure what that means. I don’t think it is anything bad though, because Louis and Kevin were nice to us and told us about the nice beaches and they gave us nice breakfasts. Mum says Kevin is handsome.

Right, says Mr Davies, stopping my thoughts. Have you all got something?

I nod and Jenny does too and the boy next to her and the boy next to him and everybody.

Who would like to tell me in one sentence about what they did in their summer holiday?