Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

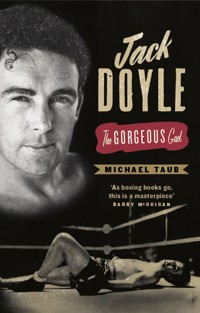

Lilliput Press is delighted to announce the reprint of Jack Doyle: The Gorgeous Gael by Michael Taub in honour of the centenary of his birth. Jack Doyle was a 6ft 5in Irishman with a giant appetite for life. In 1933 he drew 90,000 to London's White City to see him fight and was making £600 (GBP) a week on stage as a singer. He was 19. By the age of 30 he had earned and squandered a £250,000 fortune (worth millions today). His motto was, 'A generous man never went to hell,' and he lived his life like a hellraiser. In his heyday as a heavyweight boxer, singer and playboy, his celebrity rivalled the Prince of Wales, and he and his wife – the beautiful Mexican film star and singer Movita, who later married Marlon Brando – were as popular in the thirties and forties as Olivier and Leigh or Burton and Taylor. This remarkable biography rescues a glittering period of social and boxing history from obscurity and restores Jack and Movita to their rightful place in the showbiz and sporting pantheon. Jack's ring presence and personality reached back to the days of the Regency Buck and his friendships with the Royal Family, his fist-fight with Clark Gable, his life as a film star and gigolo, his throwing of a fight by knocking himself out, and his extraordinary post-war career as an all-in wrestler, are the stuff of legend confirmed here by seven years' exhaustive research, during which Taub tracked down and interviewed the leading player's in Jack's life. The book was released in autumn 2007 in conjunction with the screening of the RTE documentary "Jack Doyle: A Legend Lost", for which Michael Taub acted as consultant and in which he appears throughout.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 808

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR THE 2007 EDITION

‘This is a truly great book. It tells the truth about Jack Doyle; about how he was done down by his manager, Dan Sullivan, and Sullivan’s gangland cronies, the Sabini brothers; and about the death threats Jack and I endured. None of these things was ever reported in the newspapers. Jack was not a bad man – never. He was sweet and sensitive, like a child. He hurt me, yes, but I loved him then and I love him now. I guess I’ll always love him.’

MOVITA CASTANEDA

‘This is a fascinating account of the amazing life of a man who had it all – dashing good looks, punching power, charm and a marvellous singing voice. Jack Doyle mixed with the Hollywood elite and British royalty. Close on 100,000 turned out in 1933 to watch him fight Jack Petersen for the British heavyweight title. But Jack had an insatiable appetite for the good life and it eventually brought him down. He lived a roller-coaster existence which Michael Taub brilliantly portrays in this meticulously researched book. You will not want to put it down.’

BARRY McGUIGAN

‘I have some great memories of Jack – especially during our shambles of a tour of Ireland! – and Michael Taub’s book brings them flooding back. It’s a joy to read.’

SIR HENRY COOPER, OBE

‘I was handed a copy of the book by the late, great Denis Howell, my mentor in the House of Commons and the best sports minister this country ever had. He said to me, “You must read this book”. I found it one of the most thrilling books on boxing I’d ever read. And as a former colonial boxing champion, I hope I know what I am talking about!’

LORD PENDRY

For Martha, Kevin, Vanessa and Siobhan, who have suffered my preoccupation with Jack Doyle with patience and good humour.

Contents

Foreword

We all love a hero but we tend to love a flawed hero even more. George Best springs immediately to mind.

Before World War II another young Irishman, a practitioner in an unrelated sport, was the George Best of the pre-television age. He was Jack Doyle, a giant of a man in every way, a heavyweight boxer with a knockout punch who would have become world champion had his dedication matched his self-promotion.

The charmer from Cobh in County Cork stood 6 foot 5 inches, had the looks of a movie star and a lilting tenor voice. He married the Mexican film actress and beauty Movita, later to become the wife of Marlon Brando.

Jack was a playboy, a libertine and, eventually, a drunk who, at the time of his death in the late 1970s, was a virtual down-and-out.

The book is a labour of love by Michael Taub. When it was first released a few years ago I wrote in a Sunday newspaper that it was the best sports book I had read in an age. Revisiting it now has been a joy all over again and if the name Jack Doyle has not yet registered with you, it certainly will after reading this riveting account of his life.

Too talented in so many ways for his own good, Jack could not live up to his billing; but then, how many of us can? In his character and the perceptive telling of his story, you will probably find a little of yourself. Your first problem, though, will be ever to put this book down.

This is an outstanding tale of fame, fortune and failure, beautifully written by an author with a love and understanding for his subject without ever avoiding the harsh realities of Jack’s darker side.

DESMOND LYNAM, 2007

Acknowledgements

There are many to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. Foremost among them is Helen Doyle, whose husband Bill was the one person privy to the truth about his famous brother. He was Jack’s famous aide and companion in London and the United States from the age of fifteen and knew all there was to know about his fighting and his loving. He had turned down several would-be biographers and only after being prompted by Helen did he agree to meet me. He and Helen stuck loyally by me when his help was further requested. My biggest regret is that he did not live to see the completion of the book. Since his death Helen has given me every possible assistance, including access to their treasured photo album of Jack. Some of those pictures appear in the book.

Other members of the Doyle family were equally helpful in laying bare the details of Jack’s life, wherever it might lead me and whatever hurt it might cause them. It takes a special kind of courage and a special kind of trust. I would like particularly to thank Ted Doyle, Tim Doyle, Bella Doyle and Bridie Gibbard (née Doyle), all since deceased, and Mick Doyle.

A book of this nature cannot be produced without the backing and encouragement of a whole host of people. I wish to pay tribute to my agent, Jonathan Williams, and the MD at publishers The Lilliput Press, Antony Farrell. Also my original editors Jeff Cloves and Dominique Shead.

The following helped greatly in locating people and documentation:

IntheUnitedStates: Movita, the late Keith McConnell, Philip Paul.

InIreland: Morgan O’Sullivan, Patrick Myler, Tim Cadogan, Sr Margaret McFadden, the late Denis Morrison, Dave Guiney, Spike McCormack, Peter Barry and John McGinn.

InFrance: The late Jacques Descamps, Robert Papon.

InAustralia: David Jack, Caroline Shone.

IntheUnitedKingdom: John Morris, Lt. Morgan O’Neill and Colour Sergeant Brian Hazard BEM (Irish Guards), Peggy and Velimir Stimac, Dr Richard Agius, Martha Taub, Madeleine Smalley, Alex Toner, the Notting Hill friends of Jack Doyle; the late Gilbert Odd, Ron Olver, Frank Duffett, Jim Doherty, Tony Ross, Vic Hardwicke and Siggy Jacobsen.

It is not possible to name the numerous others who assisted in small yet important ways, but I am no less grateful to them all.

The quest: An introduction to the Lilliput edition

The date: 12 November 1981. The time: nine-thirty in the morning, GMT. Christine Cromwell was calling from her Florida hotel suite, drunk and in tears. She had endured a night of torment distilling the news in my letter: Jack Doyle was dead.

She poured out her heart: ‘My darling Jack, my baby; I can’t believe it. He was the love of my life.’

The daughter of the late Delphine Dodge confirmed with that emphatic last sentence precisely what I had always suspected: she had carnal knowledge of the man she affectionately called Mr Blarney, having pursued him lustily from the age of fourteen. It had been difficult to dismiss her heartless goading of her immensely wealthy but emotionally insecure mother – ‘You’ll never marry Jack; he likes me more than you!’ – as childish infatuation. Her missives to Jack, written in 1965 when in her early forties, and which I had stumbled upon purely by chance, proved it had been anything but.

‘I’ll tell you about that place in Windsor,’ she cried. ‘Horace Junior had prostitutes there; it was a den of vice, pure and simple.’ I said I would drop everything and fly out to see her. She was elated, offering even to pay my airfare. I booked up and faxed her my itinerary: I would be with her in Coral Gables in forty-eight hours. I could hardly wait to get the low-down on her love affair with Jack and the secrets contained within the walls of the mansion the Dodge family had provided rent-free to US ambassador Joseph Kennedy during World War II.

On the very eve of departure, while working at my job in Fleet Street, my family relayed to me an urgent message: Christine Cromwell’s attorney had forbidden her to see or even speak to me. I was devastated. Having finally homed in on one of two remaining Dodge divas privy to the peccadilloes and sexual excesses of one of the richest families on the planet, I was effectively being warned off.

I had a simple decision to make: either to accept the situation or jump on the plane and attempt to force the issue. Buoyed by a sense of purpose and even destiny, I chose to take the leap of faith that, lawyer or no lawyer, I might yet get an opportunity to confront her. I sent a defiant message saying it was too late to cancel and that I would be ‘flying into Miami as arranged’.

If all was lost, I reasoned, I had the address and telephone number of former Ziegfeld beauty Martha ‘Mickey’ Devine, the third and evidently most alluring of Horace Dodge Jnr.’s quintet of wives (all of whom would take him for a fortune), although by August 1943 – by which time Mickey was suing for divorce – his feelings toward her had turned from lifelong love and devotion to insidious loathing, to the extent that he burst into her Park Avenue apartment and ripped every piece of jewellery from her body.

I had dismissed as fanciful the promise of a consolation prize from Christine: she would press the president of Columbia Pictures to produce a movie from the book. It was a tough call on my part, and possibly a foolhardy one. Christine, I knew, would be incredibly well connected and yet I considered it some kind of ploy, a sop she had thought I would be unable to resist. She was wrong. I had also by this time made contact with Movita, who, to my surprise and delight, would willingly testify to her turbulent years with Jack. Before leaving London, I confirmed she was available for interview.

There was no one at Miami International Airport to meet me. I felt lonely and dispirited. Christine had told me of her personal assistant, Alan DeJohn, a Virgin Islander she had befriended and was putting through business school. She also had a ‘very able’ male secretary, a Mr Sol Hershman. They would be tough nuts to crack.

I took a taxi to the David William Hotel and booked myself a room. I picked up the phone and asked for Miss Cromwell, who occupied the sumptuous tenth-floor suite. Alan DeJohn answered. I told him who I was and that I had checked into the hotel. He asked for my room number and said he’d be in touch. Half an hour later, there was a knock on my door. I was confronted by a big, strapping, black man in his early twenties, well dressed and wearing expensive-looking silver-framed glasses. He announced himself as Alan DeJohn and I invited him in. He stated apologetically that Miss Cromwell was ‘out of town’ and that only that morning he had taken her to the airport, pushing her in a wheelchair through vast crowds of people and placing her on a plane destined for one of the small islands off Miami, the name of which he could not recall. Her son, he said, was going through a particularly painful divorce and she ‘just had to be with him’.

He sounded earnest and convincing and I had no reason to doubt him. He asked what my plans would be now that I was unable to meet Miss Cromwell. I said that after a good night’s sleep I would hire a car and travel upstate to Jupiter Island, where I hoped to see Mickey Devine, after which I would fly across to Los Angeles to meet with Movita. He again apologised for Miss Cromwell’s absence and said he would call in to see me before my departure next morning.

I awoke with a start, the realisation dawning that the story fed to me by Mr DeJohn was a work of fiction. I was incensed that I should have been regarded as a soft touch. I resolved to prove otherwise.

Mr DeJohn appeared at my door bright and early, kitted out head to toe in dazzling white tennis gear. He explained he was going for a lesson and had called to say goodbye. He once more expressed regret at the ‘mix-up’ over Miss Cromwell and wished me the ‘very best of luck’ in my quest.

I watched him leave the building and took the lift to the tenth floor. I knew I had an hour at most and must make every second count. I tapped gently on the door just to the left of where I had exited the lift. A Spanish maid half-opened it, peering out suspiciously. ‘Ah, yes,’ I said with supreme self-confidence (and legs of jelly). ‘I’ve called to see Miss Cromwell.’

She held her hands to the side of her face, inclined her head slightly and said: ‘Mees Cromwell, she is a-sleepeeng.’ At that precise moment I knew my instincts had been correct: Christine Cromwell was indeed here in the hotel and I had to act smartly if I was to see her. I moved to the door to prevent the maid closing it, explaining reassuringly that ‘Miss Cromwell knows I’m in town and wouldn’t mind, I’m sure, if I came in and waited for her.’ With those words I eased my way into the huge room, gestured toward the settee and said, ‘I’ll sit here quietly until she wakes up.’ The maid was wary but at the same time relieved that I did not appear to pose a threat. She was placing implicit trust in me, a total stranger.

Five minutes passed: I had counted every one of them. I had to make a move before this huge man arrived back in his tennis gear and threw me from the window to a vain and inglorious death, as I imagined he might. I got up from the settee, my eyes fixed firmly on the maid. I backed my way slowly into the short passageway leading to the bedroom, holding up my hands and saying, ‘I’m going to wake Miss Cromwell. Don’t be alarmed. I know she won’t mind.’

Christine was sound asleep and looking pretty much as I remembered her from a photograph taken nearly twenty years earlier with her banker-turned-diplomat father James, though perhaps a little old for her years (she was then in her late fifties). Walking frames were propped up against a wall and I realised she must be crippled with arthritis or some other such debilitating disease, resonating strongly with Alan DeJohn’s account, albeit fictitious, of him pushing her in a wheelchair through the crowded concourse at Miami International Airport.

I tapped her gently on the hand. Her eyes opened. I spoke barely above a whisper: ‘Christine, it’s Michael. I knew you were here and I had to see you.’ She displayed not the slightest sign of distress. ‘Alright, Michael,’ she said, calm as you like. ‘Wait out there in the lounge – I’ll be with you shortly.’

I did as I was asked. I heard the shower going. ‘Hurry, hurry,’ I was saying to myself. She did not hurry enough. In walked a casually dressed man I assumed at once to be the redoubtable Sol Hershman. He was small and slight and bespectacled and not at all the imposing figure I had envisaged. He smiled and bade me a cheery ‘Good morning.’ I returned his greeting, feeling obliged to mention that I was ‘just waiting for Miss Cromwell’.

‘Sure, fine,’ he said, before disappearing toward Christine’s bedroom. A minute or so later he re-emerged, brusque and businesslike. ‘Michael, you have to go. Miss Cromwell does not want to see you.’ I tried my best to brazen it out: ‘Miss Cromwell has just said she would see me. I’m going nowhere.’ He became agitated, threatening: ‘If you don’t go right now, I’ll call the cops.’

It was tough conceding defeat, particularly after a journey of 4000 miles, but there was the dubious satisfaction of having given the undertaking my all. I left her a piece of pricey Wedgwood pottery I had brought from England as a gift; and was at pains to absolve the maid of blame for my having been able to enter the inner sanctum of a Dodge family member virtually unchallenged. Touchingly, she appeared to appreciate what I was saying: she told me with her sad brown eyes.

The armed security guards at Traverse Circle were, paradoxically, the quintessence of charm and civility. Every few minutes, they insisted on ringing the home of Mrs Martha Gerlach (Mickey Devine as was). ‘Maybe she’s shopping; maybe she’s away’ I hung around for a couple of hours before heading off for a quick bite to eat. During my absence of all of twenty minutes, Mickey – wouldn’t you know it? – had arrived back. ‘We’ll ring her for you right away.’ My heart was pounding as I took the phone and duly introduced myself, outlining my mission and wondering if she ‘might spare the time to talk’. Her answer was an uncompromising ‘No.’ I pleaded and cajoled and remonstrated but nothing would convince her to change her mind. This was one tough cookie, evidenced by the fact she once socked 6ft-8in. Primo Camera on the jaw in a Paris nightclub.

I felt I had better change tack: ‘In a spirit of friendship, let me at least come and see you. I won’t ask questions. A quick cup of tea and I’ll be on my way’ Even that failed to move her. Finally, I said that my research had revealed a physical liaison between her and Jack Doyle: ‘I’m giving you the opportunity to put your side of the story. Otherwise, I’ll go with what I’ve got.’ That did it. ‘Write what you like,’ she said before banging down the receiver.

From Florida I flew on to Los Angeles, where my faith in human nature was restored by a warm and gracious greeting from Movita, looking incredibly young and glamorous at sixty-four. She and the tall, fair-haired, fifty-something Keith McConnell, though not living together, had maintained the friendship formed in Dublin toward the end of the war. Out of the blue, she asked: ‘Why don’t you try and see Marlon? I know he’s in town – I was with him only yesterday.’

It was pitch black as Keith and I headed off in his huge black Mercedes. On the way he told me what ‘an absolute bastard’ Brando had been during the remaking of MutinyOnTheBounty in 1962, in which Keith himself had a bit-part role. ‘He was so objectionable, the shooting of the movie became a nightmare for the whole crew. The director, Carol Reed, quit in disgust.’

Keith glided to a halt directly opposite the Brando residence on Mulholland Drive. As he did so, a car was entering through the automatic gate. Keith revved the Merc’s engine: ‘I’m going in right on its coat-tails.’ He careered across the road but screeched to a halt as the gate began its descent. We cursed our luck. I got out of the car and asked through the intercom to speak to Brando. ‘He ain’t home,’ was the response of a spaced-out young lady, in all probability tragic daughter Cheyenne. I scribbled a note and placed it in the mailbox. Brando never got back to me but, as it turned out, I wouldn’t need him. My interviews with Movita produced more than ten hours of taped testimony while Keith provided not only magnificent quotes and a compelling critique of Jack but documentary evidence relating to the darkest days of the marriage. Sadly, he has since died but Movita, as I write, is still going strong at ninety.

Next on my list was the much-married Judith Allen, who had been divorced from husband number seven by the time we met. I had been trying for years to locate her whereabouts and succeeded only by virtue of the efforts of a long-time friend in New York, Philip Paul, working in conjunction with a police chief cum movie buff from North Carolina.

By then in her seventies and in delicate health, she was trading as The Revd Judith Rucker, which explained the difficulty in tracing her. She was based at the Institute of Mentalphysics in Joshua Tree, California, part of the Yucca Valley region of the Mojave Desert, where scorpions and rattlesnakes abound. I stayed more than a week in the bungalow adjacent to Judith’s, spending entire days and evenings in her company. She was a wonderful host and willing at the drop of a hat to discuss virtually anything about herself, including the most intimate details of her marriage to world champion all-in wrestler Gus (Cannonball) Sonnenberg, news of which had shocked even hardened Hollywood sceptics and resulted in the mercurial Cecil B. deMille tearing up her movie contract.

Gus was so enormous, I couldn’t have intercourse with him; it was just too painful. On our wedding night I was torn to shreds: I couldn’t walk for days. He was booked on a wrestling tour and my mother had to get me to the hospital. The doctor there was appalled; he said my husband should be locked up and that I had to leave him immediately. But he had it all wrong. Gus wasn’t a brute in the bedroom: he was a gentle and considerate lover. It’s just he was way too big.

The brief and pain-racked union with Sonnenberg, whom she had wed at nineteen, might reasonably have been expected to turn her off sex for life; but far from it dimming her ardour, she admitted she had struggled throughout her career to control her libido, as a consequence of which Gary Cooper and Jack Doyle would appear to have been the main beneficiaries. Of all her many husbands and lovers, she maintained that Jack was ‘the best, absolutely’.

Visits to the United States had become almost de rigueur. There were, in addition, numerous trips to Ireland and to various destinations in the UK, notably to Lynton in Devon to interview the quixotic Sir Atholl Oakeley. I headed, too, to France in the hope of tracking down Jacques and Denise Descamps, whose once-famous father, François, had attempted in 1933 to transform Jack into ‘the new Carpentier’.

On arrival at the village of La Guerche-sur-1’Aubois, some 150 miles south of Paris, I was reduced to asking a woman in the street in halting phrase-book French if she knew the whereabouts of the Descamps family. She popped into a doctor’s surgery and emerged with the receptionist, to whom I repeated my request and who, in no time at all, was surrounded by a group of a dozen or so women, young and old, big and small, and all of them babbling excitedly. Finally, the receptionist hopped in her car and returned with a local schoolteacher, M. Robert Papon, who spoke the most perfect English. He invited me to visit him that evening.

In the meantime I managed to locate the street named after the great manager – rueFrançoisDescamps– and the former Descamps family residence, where Jack had been based during his two-month tutorial. I visited also the local graveyard where generations of the Descamps family are entombed. At M. Papon’s house I was introduced to Madame Paulette Desphilippons, aged ninety-one and a prosperous former market fruiterer, who revealed that Jacques and Denise were resident in Paris. She provided me with an address for Jacques in the Saint Germain district of the city.

I turned up unannounced at his apartment to explain that I was writing a book on Jack Doyle, whom he remembered with affection, and that I had travelled from London via La Guerche to see him. He wiped away a tear when I mentioned Jack’s sparring partners of the day, Maurice Griselle and Marcel Moret, saying: ‘No one in France today would have heard of them and yet you, an Englishman, arrive on my doorstep and start to speak of them.’ He explained that Denise was unwell and unable to receive visitors, which saddened me more than he would know. Unusually for me, I accepted the situation without question for fear of offending this decent and kindly former French war hero. We corresponded after my visit and then I heard nothing more from him. Shortly afterwards, I learned he had died.

As I believe I have illustrated, the task of bringing to completion the biography of Jack Doyle was about very much more than writing. It required patience and persistence, the skill and cunning of a detective, a skin as impenetrable as a rhinoceros hide and, above all, passion. It took seven years to identify and track down the major players in Jack’s life, one contact often leading to another. The search for the real Jack Doyle had turned from being a fascinating job of work into a magnificent obsession.

And so, seventeen years after the book was first published in September 1990 as JackDoyle:FightingForLove, we have a new edition with a new subtitle and a new audience. My hope is that it will prove richly entertaining and informative for you, the reader, and final arbiter.

MICHAEL TAUBBerkshire,England,September2007

JackDoyle

Some think he might have won the crown

That now to Brown Joe’s head seems glued

But he got tangled in the gown

Of Venus waiting as she would

For the handsome boy who comes to town

PatrickKavanagh

Hollywood, 1938

‘Hi Movita! It’s me. Alex.’

‘Who?’

‘Alex – Alex D’Arcy.’

‘Oh Alex! Sorry, I’ve just come from the studio – I’m not thinking straight.’

‘Listen, never mind that – guess who’s come to town?’

‘I’ve no idea. Surprise me.’

‘JACK DOYLE!’

‘Jack Doyle – wow. The guy in jail?’

‘You got it.’

‘What about him?’

‘Well, he’s out of the slammer. I’m throwing a party for him on Saturday. And get this! He wants to meet you.’

‘Me?’

‘Yeah honey, you. I’ve told him all about you.’

‘I’d love to be there. I saw his picture in the paper. He’s some guy. But I’ve got a weekend date with Howard.’

‘Where’s he taking you?’

‘Palm Springs – in his private plane.’

‘Damn! Jack’s dying to meet you.’

‘But Alex, Howard’s got first claim on me.’

‘Aw, screw Howard Hughes. This Doyle’s a real man. Listen – you two are just made for each other.’

‘Don’t get me wrong – I’m dying to meet him. But what can I do about Howard?’

‘Are you crazy? This guy boxes, sings, acts, gets slung in jail – the whole town’s talking about him. He’s dynamite. Come on! Ditch Howard. He’s a bore.’

‘Okay, Alex – you’ve sweet-talked me into it. I’ll find a way out. I’ll meet him.

‘Movita, you’re a doll. You won’t regret it – I promise.’

Book l

JACK

Chapter 1

The Holy Ground

He was almost too young to be a hero, this boy of 19 whom fame had beckoned. Even heroes are allowed to catch their breath, and he had not quite counted on the whole harbour town of Cobh* turning out to greet him. Nor had he imagined that a pipe-band would be waiting to parade him along the waterfront and out to the Holy Ground, where he was born. He was shaken by the magnitude of the welcome as he waved to the hundreds who lined the route, many of them hanging from upstairs windows. All were anxious to catch a glimpse of the handsome buachaill who had grown up in their midst and whose fighting deeds had given them cause for rejoicing. He was their local boy made good, their chieftain returning from glorious battle.

His brother Bill, then 15, recalled:

‘He jumped up on to the sea wall and made an impromptu speech: “My next aim is Jack Petersen and the British title. Then I’ll be after Larry Gains and the Empire title. And after that it will be full speed ahead to the championship of the world.” A mighty roar went up and someone asked him to give them a song. He sang MotherMachree just for Mum and you could have heard a pin drop. People were crying, so beautifully did he sing it. Afterwards they shouted things like, “We love you Joe. We’re proud of you.” He had them all in the palm of his hand and he knew it. He was a majestic figure.’

Sadly for ‘Joe’ it could be only a fleeting visit. Brigadier-General Critchley had wasted no time in arranging his next contest. It was to be at the Royal Albert Hall in just three weeks’ time and, against a Frenchman whose name he could not even pronounce. He had not wanted to fight again so quickly. Already he’d had eight bouts in his first six months as a professional boxer and he needed a break. He would have preferred a little time to savour his success – to get the feel of being famous. But he had no option other than to go through with the contest, if only to appease his new master. The Brigadier had a reputation for being as prickly as the thin moustache that lined his upper lip.

Before heading back to London, he decided to steal a few days to renew old friendships. He would step back from the present and remind himself how life had been just a few short years earlier, before his sudden rise to fame.

*

It had all started on August 31, 1913 – hardly an auspicious date in early 20th century Irish history, but one that would hold some significance for the world at large.

Doc O’Connor could scarcely believe it. The baby boy he had just brought into the world at 12 Queen’s Street* was the biggest he had delivered. A hefty 14-pounder.

The child was the second born to merchant seaman Michael Doyle and his wife Anastasia and they called him Joe. They already had a daughter, Bridie, and four more children were to follow – Betty, Bill, Mick and Tim.

Michael Doyle was tall, upright and God-fearing, a Cork man born and bred. He had married the tiny Stacia in 1910 when he was 41 and she just 18, a slip of a girl who, in common with her contemporaries, had nurtured one abiding ambition in life: to settle down and raise a family.

In those unpretentious days it was considered an honourable, even admirable, aspiration. Apart from the uneasy expediency of emigration, there was little other prospect for girls like her, brought up as they were to observe the time-honoured virtues of love and obedience and schooled skilfully by their mothers in the domestic requirements of sewing, knitting and cooking.

Michael was naturally proud of his children. Like many well-intentioned fathers, he hoped to see in his eldest son some of the qualities that might enable him to fulfil a frustrated ambition – to rebuild a broken dream. He remembered how, as a small boy, he had listened awestruck to his father’s tales of the dashing exploits of the Doyles of old, who, reputedly, had helped King Brian Boru banish the Danes from Ireland at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. He had heard also of a fearless uncle, said to be a boxing champion of the British Navy, who thought nothing of taking on several men on a foreign quayside to rescue one of his mates from trouble.

Fuelled with the desire to continue the family’s fighting traditions, Michael once tried his luck in the boxing ring. Having received some painful indications that his fists would never be his fortune, he toyed with the idea of entering the priesthood – an ambition cloaked more in fantasy than hard realism and which eventually came to nothing. But being both a devout Catholic and a proud Irishman, he vowed that if any child of his grew up to be a priest or a champion boxer, he would call a truce with his Maker and ask for nothing more in his prayers.

So when with a piercing cry the infant Joe announced his entry into the world, Michael could have been forgiven for thinking that his latent hopes and dreams would be realised. They had, in a sense, been reborn.

Little Joe was barely out of the cradle before it became obvious to one and all that he would never achieve the high calling of the priesthood. With a fighting pedigree stretching back 900 years to Brian Boru, it was perhaps pre-ordained that his qualities would be more pugnacious than spiritual. The inheritance would stand him in good stead. The Holy Ground was a tough nursery where the children played, or more often fought, in bare feet.

Ireland was in the grip of grinding poverty and the Doyles, like countless other families, were forced to make the best of it. Their plight could be considered worse than most after two appalling accidents left Michael permanently disabled. First, he was invalided out of the Navy after injuring his right leg in a fall from the rigging. Then, after obtaining employment in a quarry, he was blinded in the left eye when struck by a fragment of splintered limestone. He had to be fitted with a false eye and for a time thereafter was cruelly, but predictably, referred to around town as ‘Nelson’.

With her crippled, half-blind husband unable to contribute to the family budget, it fell to the spirited Stacia to take over as bread-winner. It was an onerous responsibility, but she set about it with her customary zeal and always seemed able to find some job or other that would supplement the weekly parish relief of ten shillings allocated by the local Catholic church.

She worked for a time on the farm of the town butcher, Tim McCarthy, who held the lucrative contract for the supply of meat to the British forces of occupation. McCarthy was a huge man, standing at more than six feet and weighing in the region of 20 stones. Formerly a renowned athlete and wrestler, he owned racehorses that ran under the Galtee prefix (in honour of the Galtee Mountains in his native Tipperary) and lived in a mansion called Mount Eaton, situated high up on the East Hill overlooking the harbour.

A dapper dresser in bowler hat and dark suit, and with a gold watch-and-chain dangling from his waistcoat pocket, he took a great shine to the busy Stacia – perhaps for no better reason than that she, too, hailed from Tipperary – and often helped her out with provisions for the Doyle dinner-table. He first got to know Joe when Stacia brought him with her to the farm each day, placing him on a blanket in the field while she went about her work – gathering the crops, potato-picking and the like. Tim loved the little fellow from the start and was forever sounding forth in the expansive tones that befitted a man of his stature, ‘Mark my words, Stacia, that boy will amount to something in life.’

The ruddy-faced Dr. John O’Connor was another trusty friend to the Doyles. Like Tim McCarthy he was a big man with a heart to match, his innate kindness evident in his custom of passing on clothes that his own daughter had outgrown. He held a particular admiration for Stacia and her iron constitution in the face of adversity: she was invariably bright and cheerful and never burdened others with her troubles. In private, Stacia’s stoicism sometimes faltered. On one occasion, daughter Bridie chanced upon her sitting alone in the kitchen, head in hands and tears streaming down her face. ‘Mum was desperate with worry because we were so poor. I remember her saying she didn’t know how we were going to manage.’

But manage she did and in any manner she could devise. She took on a variety of jobs, including scrubbing out the huge assembly hall in the town – a daunting task for which she enlisted the aid of Bridie. There were other, less legitimate methods of adding to the family income, such as pilfering coal from the horse-drawn cart that trundled slowly up the hill from the docks to Steve Moynihan’s coal-yard. Stacia would deposit the coal into bags and later sell it – an action perpetrated in the cause of necessity and which depleted the coal stocks by such a minute extent that the deficiency was never noticed.

In spite of their impoverished circumstances, the Doyles were a contented and close-knit family: Michael a mild-mannered man with an easy attitude to life and Stacia the family hustler, always beavering away at some task or other and gently but firmly cajoling the children to action.

Home was one of the huge tenement houses that fronted the water’s edge in the heart of the Holy Ground. They were cold and uninviting but the families that lived there – three or four of them to each house – were happy just to have a roof over their heads. The Doyles’ small, cramped living accommodation on the third floor of 11 Queen’s Street, into which they had moved from No. 12 next door, was sparsely furnished but spotlessly clean. The focal point was the kitchen, in the middle of which stood a large table that Stacia, a stickler for hygiene, insisted on scrubbing meticulously, kitted out in a starched white apron. The kitchen, which served also as dining room and lounge, contained a huge, open hearth on which were hung pots and pans and all the paraphernalia of day-to-day living.

There were two bedrooms, the larger of which was divided by a curtain. Bridie and Betty slept on one side and the boys on the other. The beds were the old-fashioned iron type, the mattresses home-made and filled with straw. The one lavatory, shared by all the occupants of No. 11, was situated outside and access to it involved a lengthy descent of three flights of stairs followed by an unwelcome walk to the back of the yard. Small wonder, then, that chamber-pots were always readily to hand at night.

With money in such short supply, the family had to make do with the barest of necessities. Most days the children ate at the convent opposite the town’s magnificent Gothic-style cathedral, St Colman’s, completed in 1919 after 51 years and standing proudly on a hill above the harbour. The convent, a refuge for the sick and needy, was known locally as the ‘Penny Dinners’ and for just such a sum the saintly Bon Secours* nuns served piping hot soup and a chunk of bread to warm up frail, undernourished young bodies in the chill of winter.

The local St Vincent de Paul Society, a Catholic charitable organisation, also helped out hard-up families like the Doyles by providing plimsolls for the children to wear during Mass. It would have been considered disrespectful, even irreverent, for them to be seen approaching the altar rail barefoot for Holy Communion. Though times were hard, faith in God and in the Church never wavered. Everyone attended Mass on Sundays and holy days. Cobh’s Catholic community was like one enormous family, its individual members going about their separate business during the week but unfailingly coming together for a powerful, prayerful, sacramental reunion on Sundays. They may have been poor, but they were upstanding and devout.

Happiness, at least, cost nothing and neither did entertainment: the Doyles provided their own. During cold winter evenings they would sit huddled round the fire in the kitchen that offered some protection from the biting winds whipped in from the Atlantic while Michael sang and played his beloved melodeon. His favourite songs were traditional ballads such as Valleyof Slieve-na-Mon,Carrigdhoun and the Cork song Bellsof Shandon. Stacia was also a beguiling songstress and from an early age the children were encouraged to contribute to the family musical evenings. Often, one or more of them would sit astride their father’s stiff leg as he sang and played. ‘We’d also take out his glass eye and clean it for him,’ recalled Bill Doyle, smiling at the memory. ‘It was just a game to us then, but later the very thought of it made me shudder.’

Michael and Stacia were delighted to discover that Joe had music as well as fighting in his blood. He developed a fine soprano voice and quickly mastered the melodeon and the mouth organ. He grew to be a big, strapping lad and became a popular figure around town – a boy the others could look up to in more ways than one. He seemed always to be the centre of attraction, the leader of the gang, the practical joker who would do anything for a dare.

In those distant days, children had to devise their own amusement. One of the most cherished pastimes in the Holy Ground was a game of pitch-and-toss under the gaslamps; another was alleys, a game similar to skittles. The boys would play till late at night and there was great consternation whenever Joe cheekily tried to trick them out of their stakes.

Joe’s pals never ceased to be amazed at his antics and often he would perform outlandish feats with little purpose other than to watch the startled expressions on their faces. On one occasion he devoured six raw turnips while the gang looked on in disbelief.

At home, too, Joe liked to cause something of a stir, particularly when it came to displaying a touch of bravado. He delighted in drinking straight from the bottle the dose of cod-liver oil that Stacia, wise in the ways of motherhood, insisted on her children taking daily. As the rest watched with a certain incredulity, for they could barely stomach the stuff, he would gulp down a huge mouthful and then grin defiantly. Joe certainly knew what was good for him: he also made regular sorties to the yard, where he would climb the ladder to the hen-house, crack open an egg and swallow it raw.

His favourite haunt in the town was the Soldiers’ Home and Sailors’ Rest, where his Uncle Joe worked. The chief attraction there was the delicious Chester cakes that were baked on the premises. The cakes were a kind of currant pudding known more commonly as soldier’s duff and they made a tasty and filling feed for hungry young bellies. Joe always went in with a halfpenny and asked for some Soldier’s Duff, whereupon his uncle – with a wink, a smile and well-practised sleight of hand – would invariably slip three or four huge chunks into a bag for the price of one. Joe could cheerfully have scofffed the lot with his huge appetite, but the cakes were always shared with the rest of the gang, rather in the manner of a general enduring the same hardships as his men when times were tough.

The devious side to Joe’s nature did not endear him to the local shop traders. One of his fondest ploys was to enter Kelly’s store armed with a stick, protruding from the end of which was a long nail which he had hammered into the shape of a hook. He would ask the proprietress, known by her nickname Moll Dooneen, for a drink of raspberry juice. While she was out at the back of the shop attending to his request, he would produce the stick from behind his back and spike cakes, packs of cigarettes and any other sundry items within reach, which he then stuffed quickly into his pockets and up his jumper before the unsuspecting Moll returned with his drink.

On other occasions, the boys would play follow-the-leader through the town, the idea being to discover who could leap highest and touch the tin shop-signs swaying gently in the breeze. ‘Joe was always last to go,’ remembered Bill Doyle. ‘He was taller than the rest of us and could generate more height. But once, when we got to Bunny Harris’s grocery store, he made a huge running jump and snatched a joint of smoked ham that had been hanging up on display. He tucked it inside his coat and we all ran like hell.’

Joe received his education, what little there was of it, from the Presentation Brothers who taught at St Joseph’s school for boys on the outskirts of town. He cut a comical figure as he trundled off to lessons each morning barefoot and wearing patched-up clothing, but times were such that Stacia had to be a genius with the needle-and-thread.

Joe disliked school intensely. He tried his best to be a diligent pupil, but the discipline administered by the Brothers was strict, the lessons dull and the confinement of the classroom restrictive. There were other, more exciting things for a robust and energetic boy to do and going ‘on the lang’ proved an infinitely more attractive proposition. Several times he was threatened with expulsion for absenteeism, but always Stacia’s intervention saved the day. She could melt the hardest of hearts and the Brothers proved no match for her.

Stacia, a fierce protector of the family reputation, also went to work on the local magistrates after Joe had been accused of killing a couple of ducks. It was an offence punishable by a spell in a reformatory, but he was let off with a warning following a tearful submission from Stacia.

Joe may not have been the most popular boy in town with those in authority, but his standing with his school-mates was of the highest order. To them he was a hero to whom they turned in times of trouble, a match for the bullies who had wronged them. Most of the disputes between the lads in Cobh were decided in a disused quarry directly opposite the school. Referred to locally as ‘The Arena’, it was a place where old scores were settled and new ones nurtured. It was an unlikely gladiatorial venue, ringed as it was by dozens of pig-pens and with a blacksmith’s forge situated in one corner. Whenever a fight broke out the smithy, Dinny Connell, would douse down his fire, remove his apron and rush across to restore order. But there were times when peace-maker Dinny got caught up in the excitement of it all and ensured fair play by taking on the role of referee.

Joe had his share of fights in the quarry but, as his reputation grew, few boys were brave enough to take him on. ‘No one dared pick a fight with him,’ recalled an old school pal. ‘He was so big and strong that he could handle two or three at a time.’

Gang fights, too, were commonplace, especially in the Holy Ground, where Joe learned quickly that the art of survival owed much to striking first and striking hard. Yet fists were not the only weapons of war: rocks were hurled and catapults fired as rival groups fought for supremacy. The Holy Ground was no place for the faint-hearted. The boys who lived there spoke tough, acted tough and for the most part were tough. But according to those who were around at the time, none was tougher than big Joe Doyle.

During school holidays, when Joe could legitimately be seen out and about during daytime hours, he worked in a bicycle shop owned by a character called Floaty O’Keeffe, who hired out his bikes on a daily basis. The boys rarely returned them on time and Mr O’Keeffe earned his nickname by ‘floating’ round town on one of his bicycles, resplendent in plus-fours, searching for the culprits.

In the heat of summer Joe and his pals would go swimming in the sea at picturesque Cuskinny, just outside town. It was a mud-flat at low tide, necessitating a walk of a couple of hundred yards or so in order to reach the water. This presented a problem for the boys, none of whom possessed bathing trunks; it meant they had to leave their clothes by the shore and walk naked out to sea. One afternoon, when they had finished their swim and were heading back across the mud-flat, they could see in the distance a group of girls who had chanced upon their clothing.

A member of the gang, Jim Doherty, remembered:

‘The girls were standing around waiting for us to return. As we got nearer, we covered out private parts with our hands and the girls started giggling. Joe decided to forget his modesty and have some fun with them. He uncovered his shaft and started waving it around. The girls were so shocked, they ran for their lives.’

Joe’s great penchant for exhibitionism, which would become outrageously evident in later life, concealed an almost intense puritanical streak that served to make him an unpredictable, even enigmatic, character. One instance was his professed abhorrence of foul language in the presence of girls; another was the unlikely choice of his Confirmation name, Alphonsus, which he was proud to adopt and then project as his middle name, the suspicion being that it provided an aura of intellectualism which acted as cover for his lack of basic education.

His schooling had ended abruptly and in somewhat dramatic fashion at the age of 12. He was by that time more man than boy, standing 5ft 10in tall and weighing around 11 stones, and his boredom with scholastic studies had resulted in his days on the lang becoming more frequent than his attendance in the classroom.

One morning he, Jim Doherty and another friend, Sharkey Griffin, decided to give lessons a miss in favour of a day’s scrumping at French’s orchard, a secluded spot on a private estate some two miles out of town. The boys gathered a plentiful supply of apples, which they then stuffed inside their jumpers, and climbed up into what was termed the langing tree – a huge, leafy oak where they would be hidden safely from view while they munched their apples and shared a joke or two.

When they emerged from the tree, Joe was cradling a young crow he had caught and which in his boyish naivety he was considering keeping as a pet. But as the three boys headed back to town they were intercepted by Jim Ahearne, a vigilant and much-feared school board inspector, and marched unceremoniously off to St Joseph’s.

‘What have you under that coat, Doyle?’ demanded Joe’s form-master Willie Murphy, a small, bespectacled lay-teacher who, in common with all who shared his surname, was referred to disparagingly as ‘Spud’.

Joe was in truculent mood and felt disinclined to answer. Murphy, a fluent speaker of the Gaelic language and a man renowned for his fierce temper, decided to waste no more words on him, whether in English or Irish; instead he selected one of six willowy canes he kept for just such a contingency and moved menacingly toward him. At that moment Joe opened his jacket and out flew the startled crow which, to the delight of the rest of the boys, circled the classroom at a rapid rate of knots before disappearing through an open window and taking to the skies.

Murphy was furious and began immediately to administer a beating, striking Joe with reckless abandon across the arms, chest and shoulders with his cane. But Spud was in for a further surprise when Joe, upset at losing the bird he had so recently befriended, grabbed him by the lapels of his coat, lifted him off his feet and shook him so hard that he resembled a puppet being jerked uncontrollably on the end of its strings. Joe then turned indignantly on his heels and walked out of the school, never to return. The incident earned him the nickname ‘Crow’ Doyle.

Children were permitted to leave school at the age of 12, provided they had a job to go to and their families were deemed to be in need of an additional wage-earner. The Doyles certainly fell into that category, having been forced to move to larger premises at No. 8 Cottrell’s Row*, a two-storey cottage which they secured from the owner, Mrs Flanagan, for five shillings a week. Mrs Flanagan, a kindly soul, lived in the house next door and Stacia used to ‘do’ for her, cleaning, dusting and polishing and the like in return for a modest recompense.

The authorities made several attempts at luring Joe back to school, but having made the break he was determined to resist their efforts. All he was interested in doing now was finding work and proving himself a man. As the eldest son he considered it his duty to provide for his parents a measure of comfort and security after the long, wearying years of struggle that had made them old before their time. He could sense that poverty was a strait-jacket of despair which sapped the spirit and undermined the will. He could see it in his father, an outwardly happy man who accepted the cruel blows that fate had dealt him, but inwardly resented the fact that his physical disabilities had forced the unnatural role of bread-winner on to his wife. Joe was not yet old enough to fully understand such things, but subconsciously his father’s sense of futility came through to him. He resolved to take on the responsibility of providing a decent standard of living for his family, though at that moment he knew not how.

Jobs were scarce for boys of Joe’s age but eventually he got fixed up courtesy of Tim McCarthy, who took him on at a wage of 12 shillings a week on the farm where he had romped around happily as a toddler while his mother worked the land.

After a time he became restless and decided to try his luck on the coal boats that sailed into Cobh. The lure of the waterfront was strong: big money could be earned there by a tough lad with a broad back and a zest for hard work. He became a quay labourer, unloading the coal vessels, and was delighted to discover he could shift as much coal as men twice his age.

The boats had to be unloaded in 48 hours or incur a punitive Harbour Board tariff. Eight men at a time worked ceaselessly from six in the morning till seven at night to clear the 350-ton cargos. There was no slacking: if you couldn’t do it, you were out. Joe’s job was to go down into the collier’s hold and fill two huge containers, which were then heaved up on a winch and their contents loaded on carts for delivery to the coal yards. It was back-breaking work down in that dark and dusty hold, but the rewards were high: as much as £3 could be earned for two days’ work.

Sister Bridie recalled:

‘Joe would come home worn out, his face, neck, arms and vest covered with soot. He would clean himself up in an old zinc bath in front of the fire and Mum used to scrub his back for him. Most of the money he earned he gave to her – and he also liked to buy her little gifts. I remember his first present was a purse. He was always promising that one day, when he was rich, he would buy her a fur coat.’

Unfortunately for Joe, work on the coal boats was irregular. With just two shipments a week, there were plenty of men willing and able to bare their backs for the chance of earning a decent wage. Between times, he helped carry the luggage of visiting Americans from the docks to the town’s numerous hotels and guest-houses. It was an exercise that earned him healthy sums in tips and afforded the opportunity of making a favourable impression on any attractive young lady who might take his fancy. He would target a family group that included a likely candidate, offer to act as porter and then attempt to engage the object of his desire in conversation as he humped the baggage into town.

His success rate was high. The friendly and impressionable Yankee girls, invariably a good deal older than himself, were captivated by his freckle-faced good looks, his mop of black curly hair and an original line in blarney that would prove irresistible to women in the years to come. Joe was to consider such relationships a more important, and certainly more enjoyable, aspect of his education than anything he could have learned at school; to him, it was an invaluable part of growing up. Yet though he seemed able to sweet-talk his way into the affections of total strangers, Joe rarely enjoyed similar success with the local girls. They were mostly good Catholics and on their guard against red-blooded youths seeking to prove their manliness.

By the age of 14, Joe’s massive build made his jacket appear as if it had shrunk in the wash. Other boys, puny by comparison, were suspicious of his fine physique and jealously accused him of wearing padding. Joe did not take offence at these jibes; instead, he capitalised on their doubts by taking wagers on it. Bets struck, he then delighted in removing his jacket and shirt to reveal a torso of which any grown man would have been proud.

It was around this time that Joe came across an instructional book on boxing – HowtoBox by Jack Dempsey, one of the roughest, toughest fighters in the history of the heavyweight division. Dempsey had recently lost his world championship to Gene Tunney but his hold on the title in the seven years from 1919-26 was of such destructive and explosive dimensions that it would secure his immortality in a boxing sense and earn him a place at or near the top of anyone’s list of all-time greats. Quite what technical qualities Dempsey felt he possessed that qualified him to write a treatise on boxing would have been lost on those who saw him only as a heavyweight of primitive power and savagery who scorned defensive postures and whose fighting style displayed not an atom of skill or subtlety. However, to anyone unconcerned with the niceties of the sport, and intent only on learning how best to club an opponent to the canvas in the shortest possible time, there could have been no finer tutor.

Dempsey’s inspirational words had a profound effect on Joe’s fertile young mind. He read each page with wide-eyed amazement, and from that moment his destiny was shaped. He vowed there and then that he would one day win the world heavyweight championship for Ireland. He would become the Irish Jack Dempsey, he affirmed to himself over and over again. It was an ambition that was to transform his character and personality. He even decided he would adopt the same forename as his hero when the time came to commence his career as a fighter, in much the same way as he sought to project Alphonsus as his middle name.