Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'A riveting detective story … Revelation follows revelation.' – Benedict Allen, author, explorer and TV presenter James Fitzjames was a hero of the early nineteenth-century Royal Navy. A charismatic man with a wicked sense of humour, he pursued his naval career with wily determination. When he joined the Franklin Expedition he thought he would make his name; instead the expedition completely disappeared and he never returned. Its fate is one of history's great unsolved mysteries, as were the origins and background of James Fitzjames – until now. Fitzjames packed a great deal into his thirty-two years, from trips down the Euphrates to fighting with spectacular bravery in Syria and China. But he was not what he seemed. He concealed several secrets, including the scandal of his birth, the source of his influence and his plans for after the Franklin Expedition. In this definitive biography of the captain of HMS Erebus, William Battersby draws extensively on Fitzjames' personal letters and journals, as well as naval records, to strip away 200 years of misinformation, enabling us to understand for the first time this intriguing man and his significance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The late William Battersby was a trained archaeologist and pilot who analysed the Franklin Expedition and published important new research into it.

PRAISE FORJAMES FITZJAMES

‘William Battersby’s work is the first to delve with any depth into the life of the third-in-command [of the Franklin Expedition] – James Fitzjames. Through painstaking research Battersby has detailed the life of the ambitious, accomplished and personable young naval officer.’

David Woodman, author ofUnravelling the Franklin Mystery

‘I commend this intriguing and interesting life of James Fitzjames, captain of HMS Erebus, during her ill-fated Arctic voyage, under Sir John Franklin’s overall command.’

Ann Savours, author ofThe Search for the North West Passage

‘A riveting detective story that reveals a whole host of compelling details about the nature of nineteenth-century maritime endeavour, and the fated, enigmatic Captain Fitzjames … Revelation follows revelation – a worthy addition to the distinguished literature on the greatest Arctic naval disaster in history.’

Benedict Allen, author, explorer and TV filmmaker/presenter

This book is dedicated to the memory of the late Major G.L. Dean, BA, Intelligence Corps, retired. In his old age, Admiral E.P. Charlewood described Captain James Fitzjames as ‘my dearest friend’. Guy was mine.

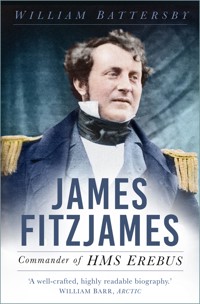

Front cover illustration: Commander James Fitzjames, a photograph of a daguerreotype, 1845. (Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, with permission)

First published as James Fitzjames: The Mystery Man of the Franklin Expedition in 2010

This paperback edition first published, 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© William Battersby, 2010, 2023

The right of William Battersby to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 182 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction:

James Fitzjames and Me

One:

Tracking Down James Fitzjames

Two:

Mr Fitzjames Goes to Sea

Three:

‘A Sailor’s Life’

Four:

Colonel Chesney: ‘A Most Determined Man’

Five:

Steaming on the Great Rivers

Six:

The Rivers of Babylon

Seven:

‘A Huge Gingham Umbrella’

Eight:

Fitzjames’ Chinese Puzzle

Nine:

Steps Towards Nemesis

Ten:

Fitzjames Prepares

Eleven:

Exodus

Twelve:

After Life

A Note on Sources

Appendix I:

The ‘Other’ James Fitzjames

Appendix II:

A Sailor’s Life

Appendix III:

Maps

Selected Bibliography

FOREWORD

On 24 March 1845, Commander James Fitzjames, RN, sat down in his cabin on board the newly commissioned HMS Erebus in Woolwich Docks and began to write:

Captain Fitzjames presents his compliments to Mr O’Brien and sends him as long since requested a rough summary of his services.

For further details of the services of himself, Commander E.P. Charlewood (now superintendent of Dover Railway) and Lieut. Henry Eden (now commanding HMS Lizard) he would refer him to the Supplementary Report on Steam Navigation to India, in 1838, which gives Col. Chesney’s dispatches on the subject.

HMS Erebus

Woolwich

24 March 1845

The Mr O’Brien (actually O’Byrne) to whom Fitzjames was writing was compiling a complete ‘Naval Biography’ of every serving Royal Navy officer and he had sent Fitzjames a detailed questionnaire. This questionnaire was the ‘rough summary of his services’ which Fitzjames was struggling to complete before his ship sailed. He detailed with care every ship he had served on, even down to short, detached duties of a few months. He completed the questionnaire meticulously, squeezing his writing small where necessary to fit all the information into the correct boxes on the form. His responses overflowed onto an extra page and a half, which he carefully attached to the original form. But he left blank the second box on the front of the form, which asked: ‘Dates of Birth and Marriage, name of Wife, and number of children? If possessing any Relatives in the Service? Their names?’

Why?

Six weeks after posting the partially completed questionnaire, James Fitzjames completely and quite unexpectedly disappeared. For ever. This book was written to answer a simple question: who was this man who hid all reference to his family and background?

I started the research which led to this book simply because I was interested in the Franklin Expedition and wanted to know where and when each member of it was born. I found that it was easy to get that information for most members of the expedition, but material on James Fitzjames was incredibly difficult to pin down. I had to go back to contemporary sources to establish anything and by the time my research was complete I had, in effect, written an entire book on this remarkable man.

Although most of what appears here is based on my own research, I have been helped by many other people. So many that it is difficult to list them all here, so to anyone who helped me and who does not appear now, I can only apologise. My thanks must first go to Glenn M. Stein FRGS, one of today’s finest polar historians, and to Martin Crozier who is, of course, related to Captain Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror. Both have been enormous sources of strength and encouragement. I would also like to thank Simon Hamlet, my publisher at The History Press, for all his support.

Many librarians and curators have helped me and must have been puzzled by the strange twists and turns of my research as I hounded the shades of Captain James Fitzjames through dusty byways of the world’s archives. Thanks to everyone at The National Archives in Kew, the British Library, the Royal Geographical Society archive, the National Maritime Museum, the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge, the National Library of Australia, the Hoare and Company archive, the Bank of England archive, the National Gallery archive, the Derbyshire Record Office in Matlock, the Hertfordshire archives at Hertford and the Wirral Archives Service at Birkenhead. Since, in many cases, I never knew your names, please do not be offended if I do not thank you in person, but I would especially like to record my thanks to Heather Lane, Naomi Boneham and Lucy Martin of the SPRI and Pamela Hunter of Hoare & Co. Many people at the National Maritime Museum have been generous with their time including Barbara Tomlinson, Virginia Llado-Buisan, Bernie Bryant, Doug McCarthy and Melissa Viscardi. I also much appreciate the kind help of Bruno Pappalardo at The National Archives. Others to whom I owe a debt of thanks include David Woodman and Ann Savours, William Wills, the great-grand-nephew of Lt Le Vesconte of HMS Clio and HMS Erebus, Dr Michael Bailey of the Newcomen Society and the indefatigable Russell Potter, Professor of English at Rhode Island University. Professors Russell Taichman and Richard Simons have also been helpful in sharing their opinions and insights. Several descendants or relatives of people mentioned in the book have been most generous including Professor Robin Coningham, Georgina Naylor-Coningham and Marilyn Hamilton. I’m most grateful to Jack Layfield, Jennifer Snell and Carol Holker for showing me at first hand so much of Sir John Barrow’s life at Ulverston. I would like to thank Captain (then Commander) James Morley, RN, then captain of HMS Lancaster, and the officers and company of that beautiful ship for their hospitality when I spent several days on board some years ago and experienced a little of life in the Royal Navy.

Lastly, but by no means least, several friends and relatives have been a great source of help and encouragement, including my old friend and drinking partner from the Institute of Archaeology, Julian Bowsher, and Dr Michael Michael. I should particularly like to thank my friends and family for much help, especially my parents Celia and Brian Battersby and my friend Rainer, Baron von Echlin, for rigorous proof reading and comments on the later drafts of the book, and my wife Julia for extremely insightful analysis of the opening sections of the book. My children Maddie, Hannah and Jamie should especially be mentioned for their initiative in baking me a fiftieth birthday cake decorated with the face of Captain Sir John Franklin and a representation of the headless skeletons in the ship’s boat at Erebus Bay – undoubtedly a first in Franklin studies.

Acknowledging that I could not have written the book without many people’s assistance, there are undoubtedly errors and omissions in this book and for them I alone am responsible.

Most of all, I hope that somewhere in the frozen shades the spirit of Captain James Fitzjames, RN, will have been amused by my attempts to wrest him back to reality. If there is an afterlife, and if he recognises something of himself in this, then it will all have been worth it.

INTRODUCTION

JAMES FITZJAMES AND ME

Like many people, there are times when I have had to travel for my work. And like all regular travellers I tend to have my own little habits. One of these is that I usually call in at the bookshop at Heathrow airport and treat myself to a history book or a historical biography before I leave. Several years ago on a regular run to San Francisco, I picked up a book by Fergus Fleming which I had seen reviewed called Barrow’s Boys: A Stirring Tale of Daring, Fortitude and Outright Lunacy. I started to read the book as the aircraft took the great circle route over northern Greenland, Nunavut and the Canadian Arctic. Visibility was good. Even travelling at nearly 600mph it takes many hours to cross the icy, rocky wastes of these northern parts. Looking out of the window I could see a vast and inhospitable landscape of rock and ice which didn’t look like planet Earth at all, but more like pictures of one of the moons of Jupiter.

Fleming’s book described the incredible adventures of groups of Royal Navy explorers sent to these uninviting wastes in the early nineteenth century. While some men died and some ships were lost, all returned to tell their tales of adventure. Except the Franklin Expedition. Fleming’s book closes this remarkable chapter in history by highlighting the horror of Sir John Franklin’s Third Expedition, which simply disappeared somewhere in the far north of the American continent. I was transfixed by Fleming’s remarkable account, and especially by this passage:

Within two years the expedition was destroyed – vaporized would be a better word – by an unknown calamity that sprayed human debris across the dark, unknown heart of the Arctic. In decades to come, explorers would pick wonderingly through the bundles of cloth, whitened bones, personal articles, stacks of supplies and scraps of wood that comprised the remains of the best-equipped Arctic fleet to have left England’s shores. Two of Franklin’s men were eventually found. They lay in a boat drawn up on the shore, with loaded muskets and a small supply of food by their sides. One, obviously an officer, wore a fur coat. Their skeletal grins gave no answer to a question that would burn for more than 150 years.

I didn’t realise then that this purple prose actually underplays the true, macabre horror of that scene. Neither skeleton ‘grinned’ because something, or rather someone, had removed both men’s skulls although their jawbones lay nearby. Dead men do not remove, dismember and carry away their own skulls after they have died. The clear implication, that someone else had taken the heads away as food, is almost too horrible to contemplate.

I decided to find out more about the Franklin Expedition. I wondered whether there was something unique about it, which had made it fail and everyone on it die when so many people on other expeditions had survived? I soon found I was not alone. Many other people had asked themselves the same question. I started to read other books on the Franklin Expedition and the huge literature surrounding it. Ever since the expedition became overdue in 1848, men have been searching for it; first for survivors, then for written records and, since the 1860s, simply for answers. Literally hundreds of books, papers and articles have been written about it and more ships and lives lost in these searches than on the expedition itself.

I found that even today basic facts, like the cause of the disaster, are disputed. Some said it was caused by dietary problems, some by climate and some by the cultural arrogance of Expedition members. There was surprisingly little consensus about anything. I read in Owen Beattie and John Geiger’s Frozen in Time that the expedition had been poisoned by the lead in their tinned food. Then I read Scott Cookman’s book Ice Blink, which said they were poisoned by botulism. The best all-round history of the expedition, I found, had been written by a doctor from Cheltenham called Richard Cyriax and published in 1939. I was lucky enough to obtain a signed copy of this book. But while Cyriax summed up the facts about the expedition very clearly and gave a wealth of sources, he was a cautious man. He did not give any ‘cause’ for the failure of the Franklin Expedition other than suggesting that the men were crippled by a bad outbreak of scurvy.

I started to appreciate that the Franklin Expedition was more than just a mystery for archaeologists and sailors. I found that, since the 1850s, its combination of real-life mystery and horror has inspired a remarkable range of fiction writers too. A diverse range of authors have been drawn to write about it, producing literature which ranges from philosophical and social discussion to downright horror. In the nineteenth century, books, plays and articles were written about it by Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, Swinburne and Jules Verne. And the inspiration lives on today. In the last twenty years the Franklin Expedition has formed the central event in a huge genre of fiction, including Sten Nadolny’s The Discovery of Slowness, Mordecai Richler’s Solomon Gursky Was Here, William Vollmann’s The Rifles, John Wilson’s North with Franklin: The Lost Journals of James Fitzjames, Dan Simmons’ The Terror and Clive Cussler’s Arctic Drift. And, from the nineteenth century on, it has also inspired a wide range of songs, poems and paintings. The respected Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood has gone as far as to say that the Franklin Expedition has become more than mere history and now lives on as a universal myth.

I realised that what had attracted my attention had inspired many others. This was not just an archaeological puzzle. The elemental horror of a community of men, for such is the company of a ship, cut off from all humanity in a frozen desert and condemned slowly to die touches people everywhere.

I originally trained as an archaeologist so I was accustomed to the concept of collecting disparate data and then trying to makes sense of it through objective analysis. Having exhausted the published books, I started to collect facts and figures about the expedition for myself. I wanted to see if I could make sense of the disaster. It was clear there were so many layers of writing about the expedition that perhaps a fresh and objective approach could yield more answers. Could I spot something that others had missed?

I found that in most cases the facts and figures were relatively easy to come by and to confirm. The plans of the ships, beautifully photographed by the National Maritime Museum, enabled me to understand how and where the men had lived and, in some cases, died. Disease seemed key, so I wanted to understand their health. I started to collect evidence of their lives. And here I came up against James Fitzjames. For most of the officers and even the men it was quite straightforward to collect material on their lives, families and careers. There are several biographies of Sir John Franklin and Francis Crozier. The lives and careers of the sailors and the Royal Marines have been clearly documented by Ralph Lloyd-Jones in his two papers published in the Polar Record in 2004 and 2005.

But although all the authorities agreed that James Fitzjames was a highly influential young man on the expedition, there were very few hard facts about him. No one agreed even, for example, on how old he was. The more I searched for information about him, the less I understood.

Because James Fitzjames is a well-known figure. He wrote the Victory Point note, which is the key historical document from the expedition and one of the few records to survive from it. He features prominently, not only in the histories of the expedition but also in the fiction. He appears in Dan Simmons’ best-selling horror novel The Terror, which is set on HMS Erebus and HMS Terror during the Franklin Expedition. Simmons says Fitzjames had been acclaimed a hero ‘before his first ship’ for rescuing a man from the sea at Liverpool and was rewarded with a silver plate. He was ‘the handsomest man in the Navy’ and ‘a well-bred young gentleman’. He had led raiding parties against Bedouin tribesmen, suffering a broken leg and imprisonment in the process. He had behaved heroically in the Opium War and was wounded. After commanding HMS Clio, he was left ashore with no job until the opportunity to be Franklin’s deputy on the Erebus gave him his second chance. Simmons says that in public Fitzjames’ demeanour was ‘an easy mix of self-effacing humor and firm command’ and that he spoke in a confident voice with a slight upper-class lisp. Simmons has Fitzjames die of botulism about two-thirds of the way through the novel, thus missing its supernatural climax.

Fitzjames is also the principal subject of a best-selling work of fiction: North with Franklin: the Lost Journals of James Fitzjames, by the Canadian novelist John Wilson. Wilson describes how he was inspired by letters Fitzjames had written in the early weeks of the expedition to an Englishwoman called Elizabeth Coningham. These captivated Wilson and he wrote the book as ‘a labour of love’. It is an imaginative reconstruction of the journal Fitzjames would have kept from the point where he disappeared. It has an apparent ring of authenticity, because in the early parts of the book Wilson freely raids Fitzjames’ letters, so it is sprinkled with comments and observations which Fitzjames actually made. It is fine writing, although still fiction, and through it James Fitzjames has won a spark of immortality.

Fitzjames also makes a cameo appearance on the very first page of Clive Cussler’s novel Arctic Drift. He is only a peripheral character in this thriller, which opens with a description of this ‘bright and affable man’ who had ‘quickly risen through the ranks of the Royal Navy’.

So though James Fitzjames died over 160 years ago, his position as third-in-command of the cursed Franklin Expedition has kept him in the public eye. But why could I not find out more about him?

Before answering that question, we need to review the story of the Franklin Expedition. Its loss was a shock to contemporary British society, comparable to that of the Titanic disaster or the loss of the space shuttles to modern American society. Exactly as with the Titanic, its disappearance and the macabre revelations of its grisly fate had the effect of signposting a turning point on the road to a more sober and less optimistic society.

The Franklin Expedition was the largest single disaster in British exploration history. The impact of its failure reverberated around the world. For Britain and the proud Royal Navy, it was a shameful defeat as every last man on it died. For the Inuit peoples of the far north it was even more dramatic. Before Franklin, they were masters of their own land and had few fleeting encounters with westerners. Searching after Franklin, wave after wave of British, American and other searchers had scoured the Arctic and mapped it. By the time the search was over, the Inuit found that, without being asked, they had become Canadians. Canada’s sovereignty over its far north owes much to this Expedition. Even before it was sent the Franklin Expedition had political significance, being a statement of British possession of the far north at a time of tension between Britain, Russia and the United States. And ironically, the shared effort to rescue it helped to heal this potential conflict and foster the eventual political settlement in North America.

For all humanity the story stands as a truly horrific chapter in history. The expedition was a living nightmare in which men fought for their lives in miserable conditions, possibly for years, before succumbing to cold, exhaustion, starvation and perhaps even murder. There is clear evidence of horrific disease and cannibalism visible in the pathetic scraps left by its last survivors.

While all the details, perhaps thankfully, will never be known, the bare facts are clear. The expedition was commissioned by the Admiralty to complete the discovery of, and then pass through, a ‘seaway’ through the ice to the north of the American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This was called the North West Passage and had been a British obsession for centuries. There were several drivers for the expedition. The political settlement in Canada was fragile and in 1845 Britain needed to maintain a quasi-military presence in the north as proof of sovereignty to both the United States and Russia. There was also important magnetic and scientific research which could only be carried out in that part of the world.

But it would not have happened in the form that it did without Sir John Barrow.

Barrow is an extraordinary figure. He was born in 1764, the son of a Lancashire farmer, and although of modest origins, had a very good education. He was essentially an accountant, a surveyor and an administrator. After working as a clerk at an iron foundry and on a whaling ship, he wangled a position on the first British embassy to China in 1792. He became a valuable member of the embassy, adding a mastery of the Chinese language to his organisational skills. He wrote authoritatively on the embassy and on aspects of Chinese culture. This made his reputation with the British ruling class as a hard-working ‘fixer’ and won him the trust of the influential Lord McCartney. When Lord McCartney was sent to South Africa to establish the new British colony of the Cape of Good Hope, he naturally took the useful and capable Mr Barrow with him. Barrow was appointed Auditor-General in Cape Town, married a local girl, Anne Maria Trüter, and settled there. The couple’s first child, George, was born and died there. But power-politics intervened. Under the Peace of Amiens of 1802 the British agreed to hand the new colony back to the Dutch, so the Barrows sold up and moved back to England in 1804. Barrow had earned the trust and respect of some very powerful people in British society and on his return he was appointed Second Secretary to the Lords of the Admiralty. He was a workaholic, a tireless networker and writer and held this post almost continually for forty years. Under him it became a position of huge influence as he directed and ran the Royal Navy. As the years of his career extended, so did the extent of his influence.

Barrow was a keen proponent of exploration and surveying and, with the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, he sent out innumerable Royal Navy ships. It was a personal ambition of this powerful and obsessive man to see a British ship sail through the North West Passage in his lifetime. And although in 1845 he boasted that he could still read without spectacles, by then he was 80 years old.

The conventional account of the expedition notes that Sir John Barrow had wanted Fitzjames to lead it because of his high birth and friends in high places. But the Admiralty rejected Fitzjames because of his youth. Then Sir James Clark Ross turned the opportunity down flat, so Sir John Franklin was chosen to lead the expedition by default at the age of 59. Most accounts suggest Fitzjames was around 33 years old. Francis Crozier was never considered to lead the expedition, despite being the Royal Navy’s most experienced polar exploration captain after Ross, so was offered the second-in-command position instead. Crozier’s recent biographer suggests that ‘his Irish pedigree was regarded as an impediment by the stuffy civil servants and admirals whose positions owed so much to the British class system’. This seems unlikely as many senior British officers had similar Irish roots. It was the Duke of Wellington, himself Irish, who famously retorted that ‘being born in a stable does not make one a horse’ when challenged over his origins. Many of Britain’s most acclaimed nineteenth-century polar explorers came from Ireland, including Sir Leopold McClintock, who was born in Dundalk, Sir Robert McClure from Wexford and Sir Henry Kellett from Tipperary.

The expedition took two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. They had been used for Ross and Crozier’s outstandingly successful exploration of the Antarctic from 1839 to 1843. For the Franklin Expedition they were fitted with steam engines and crammed with technology advanced for the day. They were packed with three years’ supply of food. Their tinned food has attracted huge attention. In the 1850s it was said that it was rotten, supplied by a cut-rate provisioner called Stephen Goldner. Goldner became a scapegoat for a wave of anti-Semitic opprobrium. We have seen that the American author Scott Cookman suggested the food was riddled with botulism, and John Geiger and Dr Owen Beattie claim it was poisoned with lead from the solder of its tins. This allegation has been repeated so often that it has become an urban myth. For many people, indeed, almost the only thing they ‘know’ about the Franklin Expedition was that the men died of lead poisoning from their tinned food.

The expedition set off from Greenhithe in May 1845 with 24 officers and 110 men in an atmosphere of great confidence. After stopping for three days in the Orkneys, it anchored off Greenland to transfer extra supplies from a transport ship to the Erebus and Terror. Five men were sent home. The remaining 129 men and the ships were last seen in early August 1845 waiting to cross to Lancaster Sound, after which they disappeared.

The story of the expedition credits Franklin’s wife Jane with being a key figure. She harangued the Admiralty to get her husband his appointment, then from 1848 shamed the Admiralty into instigating a belated search for the lost ships and men. At its peak in the early 1850s, this involved hundreds of men and no less than eleven British and two American ships. In 1850 searchers found relics of the expedition on Beechey Island where inscriptions on the graves of three men proved that the expedition had wintered there from 1845 to 1846. In 1859 a note was found, written by Fitzjames and Crozier, which was dated 25 April 1848 and explained that the ships had first tried to sail north, then doubled back south to become permanently locked in ice off King William Island in September 1846. It said that Franklin had died on 11 June 1847 and that the 105 men alive at that point apparently intended to walk to safety via the Back River to Canada. In 1854 the explorer Dr John Rae had been told by an Inuk that thirty-five to forty men from the expedition had died near the mouth of the river and that there had been clear signs of cannibalism amongst them. This caused an outcry in England. Lady Franklin orchestrated a campaign to denigrate Rae and the Inuit. Disgracefully, she induced the novelist Charles Dickens to write a polemic which traduced this with much offensive and racial abuse. Dickens called the Inuit accounts a ‘vague babble of savages’ demonstrating that one can be a writer of genius but a very poor archaeologist and forensic scientist. Archaeological evidence since uncovered has completely validated the Inuit account. Other searchers in the 1850s and 1860s brought back more Inuit accounts which backed up Rae and added much macabre detail to the stories of suffering and death.

Research has continued to this day. In the 1980s Dr Owen Beattie analysed scraps of bones from Franklin Expedition members on King William Island and found they had suffered from scurvy, cannibalism and lead poisoning. He autopsied the three men buried on Beechey Island and suggested they had died of pneumonia and tuberculosis aggravated by lead poisoning.

Inuit recollections of their ancestors’ memories of the expedition continue to bring out more information. David Woodman and Dorothy Harley Eber have both contributed a great deal by analysing these memories. Recently the Canadian government has established a major research programme, led by Robert Grenier, the senior marine archaeologist with Parks Canada, to uncover fresh evidence and to reconcile this with the known Inuit testimony. And to this day descendants of the Inuit bridle at the way they were ignored and then slandered by many of the searchers.

Like everything to do with the Franklin Expedition, Fitzjames’ posthumous reputation has swung dramatically since he vanished in 1845. First, Franklin’s men were eulogised as martyrs to British imperialism. At the turn of the twentieth century, the slightly sinister Sir Clements Markham held Fitzjames up as ‘among the most promising officers in the navy at that time … strong, self-reliant, a perfect sailor, imaginative, enthusiastic, full of sympathy for others, a born leader of men, he was the beau ideal of an Arctic commander’. Markham was 15 years old when Fitzjames disappeared so, although the two men never met, he knew people who had known Fitzjames. His description carried weight. Markham presented Fitzjames as the idealised picture of the Royal Naval officer he wanted the British to send to conquer the South Pole. It was Markham’s fantasy of Fitzjames that Captain Scott died trying to emulate.

Since then, Fitzjames has conformed to a different stereotype which holds the Franklin Expedition up as a classic example of nineteenth-century British imperial hubris. Here it is a blinkered attempt to export a hidebound and class-ridden society to the Arctic. Fitzjames and his brother officers never attempted to adapt to their environment; instead they simply sat in their ships being served preserved food by their servants, which they ate with silver cutlery off fine crockery. To add a final, delicious irony to this case, it is often stated that the food they ate was poisonous – ‘tainted’ or poisoned with lead or botulism. We have seen that Simmons has Fitzjames killed off by botulism in The Terror and Cussler takes a belt and braces approach in Arctic Drift, plumping for botulism and lead poisoning as the cause of his death.

It was clear to me that there were many unanswered questions about the expedition and especially Fitzjames’ place in it. But I found that stereotypes and posthumous grandstanding were not the only reasons for confusion in the memory of James Fitzjames. There are some very mysterious gaps and inconsistencies in all the records which relate to his life and Royal Naval service. Even information like the ships he served on, dates and ranks is contradictory and does not tie up with the questionnaire he submitted to O’Byrne. This has prevented researchers from piecing his life together from the usual contemporary sources.

Like many others who have wondered about the Franklin Expedition, I puzzled over some strange questions about him. Why was Sir John Barrow so determined the expedition should be led by this ‘engaging and able officer with friends in the right places but with no Arctic experience’, as Crozier’s biographer Michael Smith describes him? Why, when thwarted, did Barrow still send Fitzjames as Franklin’s deputy on HMS Erebus? And who actually was James Fitzjames? There are no reliable details of his age or family background in any of the standard works on the Franklin Expedition.

I found that all the modern writers based their understanding of Fitzjames on what Sir Clements and Sir Albert Markham had written about him. It was the Markhams who said that Fitzjames had been orphaned at an early age. John Wilson, in North with Franklin, says he was orphaned at the age of 7 and imagines Fitzjames having a dim recollection of his parents. Clive Cussler has Fitzjames writing letters to his family on the expedition and in The Terror Fitzjames shares a bottle of Scotch with Crozier, which he says was given to him by his father.

Another strange question was this. Everyone seems to agree that Fitzjames had great influence – ‘friends in high places’ – but no one could say why or where this influence came from. And who was this family of his?

Richard Cyriax, the great historian of the Franklin Expedition, says nothing at all about Fitzjames’ family or life before he joined the Royal Navy in 1825 except that he was ‘about thirty two years old’ in 1845. There is nothing about him in Owen Beattie and John Geiger’s best-selling history of the Franklin Expedition Frozen in Time. Other historians give contradictory information. Scott Cookman in Ice Blink gives Fitzjames’ age as 33 and describes him as ‘well-educated, aristocratic, wealthy, of good family, Church of England, fast rising in the service – and thumpingly, lispingly English to the core’. Cookman says Fitzjames was ‘aristocratic and of good family’. But how can this be so if nobody knew who his family was? Simmons in The Terror follows this, even down to the ‘upper-class lisp’.

Once I started to collect information about him I found that there were few facts about James Fitzjames, and much that was written about him was conflicting so that he himself became another of the mysteries of the Franklin Expedition.

The Royal Navy’s records relating to him are very confused and incomplete. I looked for his ‘passing certificate’ in the index at The National Archives in Kew. Every officer in the Royal Navy at the time had to pass an examination before being appointed lieutenant and on this certificate would be given a record of his prior service. Fitzjames said he passed this exam in 1833, yet his name was missing from the index altogether. Why?

I had a second-hand account of his service from the O’Byrne directory of naval officers. This was written from the questionnaire Fitzjames had been completing on the Erebus just before she sailed. I tracked down the original questionnaire which Fitzjames had sent to O’Byrne. After publishing the directory, O’Byrne had kept all the completed questionnaires, and after his death they had been deposited in the manuscripts section of the British Library. From this I could see that O’Byrne hadn’t just missed out information about Fitzjames’ family. Fitzjames himself had actually refused to give any information about them or himself at all. Not even his own date of birth.

I wanted first-hand information so I spent days at The National Archives in Kew tracking Fitzjames’ career back through the ships’ muster books. I found that there were gaps and inconsistencies in these too. For example, in his O’Byrne questionnaire Fitzjames said he had entered HMS St Vincent on 15 December 1830 and served on her until 1833 as a volunteer and a midshipman. Yet in the muster books I found that this was not true. He had entered St Vincent when he said he did, but not as a midshipman. The contemporary muster book showed that actually he entered as master’s assistant, which was an entirely different and civilian position. It then told me that he had been dismissed from St Vincent after only a month, in January 1831, and entered HMS Asia as a midshipman. Then he rejoined St Vincent in February, but this time as a midshipman. What was going on? Why should his career be so confused? Why had he apparently concealed information about some things, like the ships on which he had served, in the same way that he seemed to be hiding the identity of his parents and family?

There were more puzzles like this.

More fundamentally, I could not fathom why Fitzjames was supposed to have had such influence on the Franklin Expedition. And if it was true that he had so many ‘friends in the right places’, why was he not selected to lead it? If he was so capable and well-connected, why did he accept the lowly position of third-in-command of the expedition? After all, he had already served as captain of a previous ship, HMS Clio. This seemed strange.

The biggest puzzle was this: who was he? The very first question O’Byrne’s 1845 questionnaire asked Fitzjames was to give details of his family background. O’Byrne said this question was optional but most officers answered it at considerable length because, in their society, their families, their social origins and their naval pedigrees mattered. Fitzjames’ refusal to name his parents or even say when he was born is very strange behaviour for someone ‘of good family’. It suggested to me immediately that what we read about James Fitzjames may not be true. If he was a well-connected young officer in the class- and family-based Royal Navy of the time, then surely his connections would be plain and he would want people to know them? But if he had no family or connections, then how could he possibly be ‘well connected’? If no one can identify his family, how can anyone say that he was ‘lispingly English’? That is especially ironic given that Francis Crozier was supposedly held back because his parents were Irish. Why was Fitzjames promoted so fast if he apparently had no parents at all?

I went back to Sir Clements and Sir Albert Markham, who seem to have been used by all succeeding historians for information on Fitzjames. I consulted the Markhams’ published books and a handwritten manuscript by Sir Albert for a book he never published on the Franklin Exhibition which is deposited in the archive at the Royal Geographical Society. In this he wrote nothing about Fitzjames’ education, wealth or breeding, which is a puzzle since succeeding writers seem to be convinced that he had plenty of all three. But the Markhams did give what appeared to be two facts about Fitzjames’ family.

The first was that Fitzjames was said to be the brother of Elizabeth Coningham, the lady to whom he wrote the last letters which inspired John Wilson. The second was, rather strangely, that Fitzjames was the cousin of her husband William Coningham, as they tell us Coningham’s father Robert was Fitzjames’ uncle.

By now Fitzjames seemed to me to be a bit like Woody Allen’s Zelig. Everyone seems to know him, yet he appears to have sprung fully formed from nowhere. He was a young man who ‘rose without trace’, as Peter Cook memorably said of the television personality David Frost. I thought that with what Sir Clements and Sir Albert Markham had said I could trace his family and fill in the gaps in his career. Little did I know then that the accepted story about James Fitzjames simply didn’t add up.

This book reveals who James Fitzjames really was and it will cause quite a few surprises. The truth, revealed for the first time here, will enable historians of the Franklin Expedition to understand Fitzjames’ position and his influence on the expedition. But what is much more exciting, and what I had not expected, was that it brings back to life the exciting story of the real James Fitzjames. The true picture of the man that has emerged does not conform in the slightest to any stereotype. No one has ever understood him because no one has ever put together all the information he left behind.

ONE

TRACKING DOWN JAMES FITZJAMES

James Fitzjames joined the Franklin Expedition at the start of the photographic age. Pictures were taken of the officers of the expedition, including Franklin, Crozier and Fitzjames. These pictures are not photographs but daguerreotypes. A daguerreotype is something between a photograph and a painting. Like a photograph, it is a mechanical image, but like a painting it is unique in that it can never be reproduced. This makes them precious and to handle the original daguerreotypes, as I have been privileged to do, gives you a unique connection with the subject (see plates 1 and 2).

The often mistranslated Chinese proverb that ‘a picture’s meaning can express ten thousand words’ is certainly true of these portraits. Franklin and Crozier are identically posed. Both have problems with their hats. Franklin is wearing an archaic fore-and-aft hat and looks ill, while Crozier looks tired and wan and is wearing an improbably huge cap. Fitzjames has a rather large cap too, but as he is holding it the absurdity seems less. Two daguerreotypes were taken of Fitzjames. In one he holds a telescope, the symbol of an officer, and in the second he has put it down. He looks more relaxed and confident than Franklin or Crozier – a more modern figure. One of the daguerreotypes of him has been lost, but a photograph of it survives so both images are reproduced in this book.

These daguerreotypes are well known yet even they have concealed significant information which generations of Franklin researchers have missed. The researcher Peter Carney noticed that reflections can be seen in the peak of Fitzjames’ cap in both pictures and that, since Fitzjames held his cap at a slightly different angle, by enlarging the two images it is possible to ‘see’ what Fitzjames was looking at when he sat for his pictures. On Fitzjames’ left stood Sir John Franklin, who can be discerned wearing his fore-and-aft hat. In the centre was a mast with a lower spar and a furled sail visible from one of the ships, possibly HMS Erebus. And on the right can be seen the tripod of the daguerreotype machine. It is eerie that Fitzjames’ own image has retained, unseen for 165 years, an image of his own view of his commander Sir John Franklin and (probably) of his ship HMS Erebus.

The Markhams were the starting point for my quest for the truth about James Fitzjames, especially the handwritten draft of Sir Albert’s unpublished book on the Franklin Expedition. The other recognised source for information on Fitzjames is the published set of letters he wrote to Elizabeth Coningham, who Markham had said was Fitzjames’ sister.

Less well known is the archive of Fitzjames’ papers held at the National Maritime Museum. This includes the certificate of his baptism at the church of St Mary-le-Bone in London. It records that his father was James Fitzjames, gentleman, and his mother Ann Fitzjames, and that he was born on 27 July 1813 and christened on 24 February 1815.

Now I had confirmation of the identity of his family; but who were Ann and James Fitzjames? I tried to find out more about them. Even though detailed census records did not exist in 1815, there are many other sources of information, especially for someone who was a ‘gentleman’. Many parish records are now accessible through the internet. I tried everything. But in every single case I drew a blank. I even searched trade newspapers and Court Circulars for some sign of the ‘gentleman’ having had some sort of independent existence somewhere. There was no one of that name in the Royal Navy. I looked through the marriages and deaths registers for their parish church, St Mary-le-Bone, from 1790 to 1820, but there was nothing. There were no candidates for either Ann or her husband on any registers or databases of births, marriages and deaths. If Fitzjames was their first child and if they were supposed to have died a few years after his birth, then there ought to be a trace somewhere. The baptismal certificate proved that at some stage on Friday 24 February 1815 a couple had brought their 1-year-old baby to be christened at that church. Yet it was frustrating because I could go there and stand at the very spot where they had stood with James Fitzjames in their arms, but could not find any more information about them. They seemed to walk into the church from nowhere and then walk out again into a void.

I wondered if I could trace them through Fitzjames’ ‘sister’, Elizabeth Coningham. Here the parish records were easily accessible and proved beyond doubt that she had been born Elizabeth Meyrick in the little town of Burford in Oxfordshire. Unlike the records relating to the Fitzjames family, her family records are complete. They show that she did not have a brother called James, nor did she have any relations called Fitzjames. I checked her father’s will and again drew a blank. It seemed impossible that the sibling relationship alleged by Markham between Elizabeth Meyrick and James Fitzjames could have existed.

Markham also described Elizabeth’s father-in-law, whose name was the Reverend Robert Coningham, as Fitzjames’ uncle. This had seemed strange, but if Fitzjames was not Elizabeth’s sister, perhaps he was really related to her husband William. Again, parish and genealogical records enabled me quite easily to prove that Fitzjames was not associated with Coningham’s family tree in any way.

I noticed that in his letters to Robert Coningham, Fitzjames had addressed the older man as ‘uncle’. Markham must have seen this. Then I found official letters to the Admiralty from both Robert Coningham and James Fitzjames in which both men made it quite clear that Robert Coningham was Fitzjames’ guardian and they had no blood relationship. In most of his letters, Robert Coningham said that Fitzjames ‘was placed at a very early period of his life under my charge, and was carefully brought up under my own roof till the time of his going to sea, when he was just twelve years of age’. Sometimes Coningham says that Fitzjames came into his household at age 7. John Wilson seems to have picked up on that.

This proved that Fitzjames was not related to any of the Coninghams, but got me no closer to the elusive ‘Ann and James Fitzjames’. I started to think that perhaps Fitzjames was illegitimate and these names were false. Illegitimacy was not unusual and the accepted practice was for the resulting child to be born discretely and then quietly and informally fostered elsewhere.

It was usual for illegitimate children to be given a surname constructed from their father’s name. The illegitimate son of King James II was called James Fitzjames and the Duke of Clarence gave his illegitimate children the surname FitzClarence. It is a coincidence which threw me for a while that I found evidence of an unrelated, but clearly illegitimate, James Fitzjames who was born in 1802, entered the Royal Navy as a volunteer at age 12 and died on active service in 1822. His strange story is given in Appendix I.

So was ‘my’ James Fitzjames illegitimate too? If so then his name, which has the meaning of ‘James, the son of James’, might suggest that his father also had the first name ‘James’. And the fact that his father, if he concealed his real name, adopted the name ‘James Fitzjames’ for himself suggested to me that Fitzjames’ grandfather might also have been christened ‘James’.

Over the years there have been many different suggestions for Fitzjames’ true family. The name is unusual and at the time had strong connotations of Jacobinism (support for the exiled Stuart line of claimants to the throne). The exiled Stuart royal line used the surname Fitzjames and some have suggested that James Fitzjames’ father might have been one of them. Others have noticed that James Stephen, the famous anti-slavery lawyer, named his son James Fitzjames Stephen and have suggested that Fitzjames may have been an illegitimate son of James Stephen. A further suggestion, on the basis that Fitzjames is a common surname in Ireland, is that perhaps he was Irish. Many Irish parish records were destroyed in the early years of the last century, so this would explain why I could find no trace of Fitzjames’ ancestry in any search there.

I had spent about a year puzzling over this, exploring blind alleys and loose ends until one day, reading some Admiralty files at The National Archives at Kew, I found a personal letter which proved categorically that Fitzjames was illegitimate and conclusively identified his father. James Fitzjames’ natural father was not called ‘James Fitzjames’, was not Sir James Stephen, was no Jacobin pretender and was certainly not Irish. He was no relative of Elizabeth Coningham either. Proof of Fitzjames’ paternity lies in Admiralty file ADM1/2559, letter S10, dated 27 January 1831. This was a private letter between two senior officers, Captain Fleming Senhouse of HMS Asia and his friend Captain George Elliot, who was First Secretary to the Admiralty. In the letter, Senhouse refers to Fitzjames as ‘Mr Jas Fitzjames, a son of Sir Jas Gambier and who having served in the Pyramus under Captains Gambier and Sartorius is now on board the St Vincent as assistant master’. This was my man and my proof. It enabled me to reconstruct the story of James Fitzjames. And the story it reveals is far more remarkable than anyone could possibly have guessed.

Fitzjames’ true father, Sir James Gambier, was born in 1772 and died in 1844, shortly before James Fitzjames sailed on the Franklin Expedition. Fitzjames was not orphaned at an early age, nor at the age of 7. Sir James Gambier was a member of a prominent British family in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. He was descended from a French Huguenot called Nicholas Gambier, who had moved to England from Normandy in about 1690 to escape sectarian persecution. The family had prospered in the eighteenth century and most of its male members had chosen careers either in the Church of England or the Royal Navy.

Sir James’ father had been Admiral James Gambier, who was born in 1723 and died in the year of the French Revolution, 1789. My hunch about the forenames of Fitzjames’ father and grandfather had been correct. Admiral Gambier had fought in the American War of Independence as second-in-command to Vice-Admiral Lord Howe and had briefly been commander-in-chief at New York after Howe resigned his command.

There was a second Admiral Gambier, both more famous and more controversial, who was 57 years old at the time of Fitzjames’ birth. This was Admiral Lord Gambier (see plate 3), whose first name was also James. He was Fitzjames’ father’s first cousin. He had fought with great distinction in one of the early sea battles of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Glorious First of June in 1794, but his career ended in controversy after the Battle of Basque Roads in 1809. After this battle he was accused publicly of cowardice by Admirals Lord Cochrane and Sir Eliab Harvey after he refused to close with and destroy the trapped French fleet. Harvey told Gambier to his face, ‘I never saw a man so unfit for the command of a fleet as Your Lordship’. Lord Gambier was cleared in the subsequent court martial but never went to sea again.

Why had Admiral Lord Gambier not moved in for the kill at the Battle of the Basque Roads? The reasons lie in his personality. Lord Gambier was a career naval officer who was known for his profound Christian belief. He seems to have been unable to accept responsibility for the bloodshed which would follow an assault on a large body of French sailors unable to defend themselves.

Lord Gambier was active in missionary work and a leading light in such organisations as the Marine Society, the various Bible societies and the Church Missionary Society. Like Sir John Franklin, he was a man who was regarded as particularly pious even by the standards of the time. He was a member of the Clapham Sect, the group of committed evangelical Christians centred on William Wilberforce who worshipped at the Church of All Saints in Clapham. He was actually related to the Reverend Venn, the vicar of All Saints and spiritual leader of the Sect. Gambier’s pious nature was well known throughout the Royal Navy and made him deeply unpopular. Officers found the assertive teetotaller an uncomfortable messmate and the sailors, who evidently did not appreciate his fervent sermons, nicknamed him ‘Dismal Jimmie’.

Sir John Barrow told a story about Gambier’s behaviour at the Battle of the Glorious First of June. Gambier had been captain of the HMS Defence, a relatively small ship of 74 guns, which seemed about to be overwhelmed by a huge 120-gun French ship bearing down upon her. One of his lieutenants momentarily, and understandably, panicked at this terrifying sight and shouted to Gambier: ‘Damn my eyes, sir, here is a whole mountain coming down upon us; what shall we do?’ Gambier was more offended by this oath than by the sight of the French ship and replied solemnly: ‘How dare you, sir, at this awful moment, come to me with an oath in your mouth? Go down, sir, and encourage your men to stand to their guns like brave British seamen.’ When an incredulous Sir John Barrow later asked Gambier whether this was true, Gambier apparently murmured that ‘he believed something of the kind had occurred’.

It was probably this that prevented Gambier’s court martial from finding him guilty. It would have been extremely embarrassing for this venerable seadog and pillar of the Church to be convicted of cowardice in the face of the enemy.

This mixture of Church of England and Royal Navy was the heritage of Sir James Gambier. But Sir James broke away. He was neither clergyman nor sailor. After brief service in the Royal Navy he joined the army by purchasing a commission in the Life Guards. Then he became a diplomat, being appointed British consul-general at Lisbon in 1803. This became a vital post with the outbreak of the Peninsular War. When the Portuguese royal family went into exile in Brazil in 1808, to escape the invading French armies, Gambier was appointed British consul-general in Rio de Janeiro. Portugal and Brazil then shared the same royal family. Gambier served in this role until 1814, when the allies reached Paris and forced Napoleon into exile on Elba. Gambier returned to England in August that year at the age of 42. In 1815 he went abroad again, being appointed British consul-general to the Netherlands in The Hague, where he remained until at least 1825.

Britain’s relations with Brazil and Portugal were vital during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, and Gambier’s role had been critical. From 1808 British land forces were continually engaged with the French in Spain and Portugal in the bitter Peninsular War. Brazil was a key British trading partner and ally, especially once the cool relations between Britain and the United States descended into open warfare in 1812. Compounding British difficulties was the start of the protracted Latin American revolt against Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule in which Lord Gambier’s nemesis, Admiral Lord Cochrane, played an important role. This series of revolutions might have been expected to act against British interests and favour France as the revolution in North America had forty years earlier. But skilful diplomacy, aggressive trading and selective use of the force of the Royal Navy enabled Britain to maintain a positive position in the turbulent world of Latin American politics and to exploit these relationships to counterbalance France and the United States. Sir James Gambier played a vital part in this balancing act, working with the Portuguese royal family in exile in Rio de Janeiro from 1808 until 1814.

The life of the Portuguese expatriates in Brazil was exotic and licentious. Sir James fully entered into this and his life in Brazil was one long social whirl of luxurious living. We have an eyewitness account of this from the diary of Elizabeth Macquarie, who visited Rio and met Sir James and his wife and six children in August 1809 while on her way to Australia. She tells us that Sir James and Lady Gambier lived in a beautifully situated house called ‘Bolto Togo’ which Gambier had bought outright. The house was situated ‘in a most romantic spot’ on the sea shore surrounded by an orange grove. Elizabeth Macquarie found the smell of the orange blossom overwhelming. The house was approached by a grand drive which skirted the beach. It overlooked the harbour and the Sugar Loaf Mountain. The interior was decorated in the regency style and furnished in the latest English taste. As Gambier’s bankers would later attest, the family lived a life of ‘unbounded expense’ in which Lady Gambier fully shared. Elizabeth Macquarie described Lady Gambier as ‘one of the most elegant and pleasing women we had ever seen, and very handsome’. The Gambiers continually entertained the English community and passing English visitors and when the Macquaries visited they insisted on organising a ball for the officers of Colonel Macquarie’s regiment. At this ball, Elizabeth Macquarie met not only ‘all the English persons of distinction at Rio consisting for the most part of naval officers’, but also senior members of the Portuguese nobility and the Papal Nuncio.

But at some point in this exotic, elegant, extravagant and no doubt alcohol-fuelled life, Sir James strayed. Since James Fitzjames was born in July 1813, it is clear that in or around November 1812 Sir James was conducting an affair, as it was then that James Fitzjames was conceived.

Who was James Fitzjames’ mother? There are no clear pointers in the English records. But it seems most likely she was an unmarried woman of some social importance. Had the mother been a lower-class woman the Gambier family would not have been obliged to take responsibility for the baby. And had she been married it is likely that her family would have brought the baby up as if it had been conceived by the mother’s husband. Right from the top, the Portuguese royal family and nobility in exile were notoriously licentious. Dom João, the regent, was heir to the thrones of Portugal and Brazil. He was well known for his personal ugliness, indolent nature and corpulent physique. His wife Carlota Joaquina, daughter of the King of Spain and a member of the illustrious Bourbon family, was an even more eccentric figure. Although lively and flighty, she was renowned for her quite astonishing unattractiveness and it is a little ungallant to record that contemporary paintings of her fully bear this out. She had a persistent reputation for promiscuity. She had little in common with her husband and the couple led very separate lives under different roofs. Between 1793, when she was 18, and 1820, when she was 45 years of age, she bore twelve children, although the last three were stillborn or died in infancy. Rumours about the paternity of at least some of these children seem to have been more than just gossip.