13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

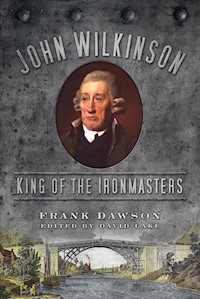

From a farming background in Cumbria, John Wilkinson's remarkable abilities and ambitions ensured his rise to pre-eminence among the gifted pioneers of the industrial revolution. His colleagues and friends were similarly talented characters, including James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Richard Crawshay and Thomas Telford. Wilkinson achieved great leaps in the iron industry and munitions, including the first use of sound castings and accurate boring for cannon manufacture, but he was also influential in the development of steam railway engines, waterways, and copper refining, and worked extensively with lead and chemicals. But while Wilkinson's technological triumphs were admired by his contemporaries, his personal affairs were complicated and sometimes tragic. This well-informed and readable book, based on research by the author born of a fascination with Wilkinson after living at his family home, gives a unique insight into the character and thinking of the man Telford named 'King of the Ironmasters'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Frank Dawson – A Brief CV

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1 Beginnings

2 Wilson House

3 Bersham – A New Beginning

4 Wealth and Acclaim

5 The New Steam Engine

6 The Iron Bridge

7 The Northern Sanctuary

8 Daughter Mary

9 Brother William and France

10 Disagreement, Dispute and Litigation

11 Quest for an Heir

12 Posthumous Rumblings

References

FRANK DAWSON – A BRIEF CV

In 1978, with an arts degree from the Open University, a diploma in education from the University of Leeds and twenty years’ teaching experience in the UK and Africa, Frank Dawson went to live and work at Castle Head, the eighteenth-century home of John Wilkinson, ‘King of the Ironmasters’. He and a group of friends had acquired the property to establish there a private, short-stay residential field centre for studies by teenage and adult students. At the start Frank knew nothing of the Wilkinsons, but folk memories of their activities in the area led to documentary research into their lives and fortunes, and then to short study courses and field excursions, which he taught and directed. Annually, for twelve years, Frank gave a public lecture at Castle Head Field Centre on some aspect of the Wilkinsons’ lives. He retired in 1997 when the field centre became part of the Field Studies Council. Since then, he has linked together a continuous story of the Wilkinsons, using further evidence gathered from private and public archives up and down the country.

FOREWORD

John Wilkinson was the important third man in the firm of Boulton and Watt, though he was never a properly constituted business partner. His acknowledged iron-making expertise and his engineering skills complemented James Watt’s inventive genius and Matthew Boulton’s entrepreneurial flair. He made the iron parts for the early Watt steam engines, suggested working modifications, promoted sales and organised transport. In the ten years from 1775, the three men were central figures in the dramatically developing industrial Britain.

Against this backdrop, documentary sources reveal a Wilkinson family drama on an epic scale: a father with a touch of genius, bitter quarrels between father and sons, the loss of beloved women in the uncertainties of childbirth, and a family in constant dealings with the personalities and events of the Industrial Revolution. Notably: the Darbys of Coalbrookdale; Richard and William Reynolds; Josiah Wedgwood; Joseph Priestley (who married a Wilkinson); and Samuel More of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, John Wilkinson’s lifelong friend. These power relationships are closely examined in the building of the great Iron Bridge over the Severn; in the litigation involving Watt’s patent; in some early industrial espionage involving the manufacture of cannon for the British Navy; and the Wilkinsons’ contact with France when she was at war with England.

Everyone has heard of Boulton and Watt; few know of John Wilkinson’s importance in their story. He created a vast industrial empire but had no son to inherit it, and his need of an heir led to a reputation in his old age as a womaniser and lecher. He quarrelled with some of his partners and with some of his family. Moreover he did not regard himself as bound by all the established conventions of the time: he consorted openly with a mistress, had three children by her in his seventies and left his vast empire to them, only for it to be consumed by litigation.

His contemporaries dubbed him ‘Iron-mad Wilkinson’. It is a sobriquet at once patronising and dismissive. John Wilkinson rose from humble beginnings to become a giant of his time, and he deserves better than that.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks go to:

Mrs Frank Dawson (Fev) for her warm support.

Vin Callcut and Neil Clarke of Broseley Local History Society for their editorial input.

The History Press for being a very clever pleasure to work with.

Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, Cyfarthfa Museum and Art Gallery, and the Royal Society of Arts for illustrations.

1

BEGINNINGS

The father of John Wilkinson, Isaac Wilkinson, the first of this family of ironmasters, probably came to Cumberland from Washington, County Durham in the late seventeenth century, but there remains some uncertainty about his origins. Recent research by Janet Butler1 indicates he was born in 1695, the youngest of six children of John Wilkinson and Margaret Thompson who were married in Washington on 27 June 1678. A bishop’s transcript of a 1705 entry in the parish registers for Lorton, Cumberland records: ‘Isaac, son of John Wilkinson, baptised 24 January’. However, this might refer to another Wilkinson family, for if one accepts Janet Butler’s dates, Isaac would have been 10 years old at this time. The further evidence, of his stated age of 80 years at the time of his death in the Bristol Register of Burials for 1784, must also be considered.

At an early stage in his adult life Isaac was a known dissenter; if he grew up with these beliefs in a family of dissenters, baptism in the established church would not have been possible. On the other hand, it may be that he developed these ideas later and that his parents, at the time of his birth, were conforming members of the Church of England.

It has been suggested, because of his subsequent close relationship with the Quaker William Rawlinson of the Backbarrow Company in south Cumberland (whose father had documented links both with the Bristol merchants and the Darbys of Coalbrookdale),2 that Isaac came north to Cumberland from the Midlands and developed his religious views from an earlier beginning. He certainly moved south to Wrexham in his middle life, but whether that was a return, or another beginning, remains uncertain. We do know that he died in Bristol in 1784 but, in the meantime, there is further evidence for his northern roots.

Firstly, we know Wilkinson is a northern, rather than a Midlands, name. The church registers in the Lake District of present-day Cumbria are full of Wilkinsons, and the IG (Mormon) Index for the old county of Cumberland lists literally hundreds of them. Secondly, there is documentary evidence to show that Isaac came to the Backbarrow Company, on the River Leven between the southern end of Lake Windermere and the sea, from Little Clifton in Cumberland in 1735.3 Little Clifton is in Workington parish, some 3 miles due east of Workington town, and about 8 miles by road north-west from Lorton. It lies in the mouth of the broad vale of the northward-flowing River Marron, a couple of miles from its confluence with the Derwent.

There is a church record, however, from the parish of Skelton, also close to Workington, for the year 1727 which records: ‘January 20th: John, son of Isaac Wilkinson and Ann his wife, baptised.’ If this is our Isaac, he was married by the age of 32 (or by 22 if one accepts the alternative evidence) to someone called Ann, whose maiden name is unknown. There is further confusing evidence for that year, too. From Brigham church, a village in the area just to the west of Cockermouth, comes a record that indicates Isaac was married there on 9 September 1727 to Mary Johnston, by banns.4 He was 23 years old at the time. The date and the name of his wife, but not his age, agree with Janet Butler’s evidence. If both records are accepted for Isaac then two things follow. First, the baptism record would mean that Isaac’s dissenting ideas could not have developed fully by that time, since his child was baptised into the Church of England. Second, his wife Ann of the January record had died, possibly in childbirth, before he married Mary in the September. A possible explanation for some of the confusion begins to emerge.

Isaac’s first marriage, sometime before January 1727, the date of the baptism of the John above, is to a woman called Ann about who little is so far known. She dies in childbirth and the infant John (who may or may not have survived) is baptised. It is perhaps this tragedy which turns Isaac away from the beliefs and practices of the established church. As a young widower, he meets Mary Johnston and marries her later that year. The following year their first child is born, but there is no church record of this birth or baptism because the father is now a dissenter. Such a scenario would be supported by all the evidence quoted above, with the one discrepancy of Isaac’s age.

It is worth repeating here the folk memory still circulating in the Workington area of the birth of John Wilkinson: in a cart, when his mother was returning to her home in Little Clifton from Workington market where she regularly went to sell her farm produce. The birth, in such circumstances, was of sufficient notice to register the local view that someday the baby ‘wod be a girt man’. Such stories handed down by word of mouth are surprisingly enduring, often rooted in fact though embellished in the telling, and stand more as an indicator than as evidence.

This story is sometimes used to support the idea that Isaac’s wife (or second wife) was a strong and healthy woman, which is likely to be so since she went on to bear him five more children. It also supports the tradition that the Wilkinson family roots were in farming, even though in his early 30s Isaac was being described as an iron founder. Little Clifton, too, is in the middle of that favoured livestock farmland between the Cumbrian Mountains and the Irish Sea, where the young sheep and cattle born on the fells and in the mountain valleys come to be fattened. As Ron Davies describes:

The area of Little Clifton today is completely by-passed by newer and faster roads, so without the aid of a detailed map it is for a stranger virtually impossible to locate. It lies cheek-by-jowl to Bridgefoot village which is set upon the River Marron, a pretty spot, boasting a secluded and ancient water-powered iron forge with an attendant weir and mill house.

The old furnace where Isaac worked stood about half a mile south from Little Clifton, but today there are no outward visible signs of such, though cinder is seen in fairly large quantities and finding a lump or two of iron is no problem.

As one would expect, the site is known as Cinder Banks, a name which has been adopted to a new bungalow recently erected upon the site. Across the field to the west of Cinder Banks is Furnace House. It now stands empty in a long and lonely lane and was probably used in days past by managers of the ironworks and possibly the Wilkinsons …5

From Furnace House, the ground slopes down gently to the River Marron and its old mill half a mile away. The view beyond to the east is across gently rolling country, the low ridge separating the Marron and the Lorton vales in the foreground and the rugged peaks and ridges of the high fells of the Lake District on the skyline beyond. Still countryside of small farms, it will have changed little since Isaac’s time.

There are eighteenth-century records of an iron furnace at Little Clifton, and it is likely that Isaac learned his iron-making skills there while his wife ran a small farm or holding that was their home. The Workington church registers from the 1730s record the christenings of several children of a ‘certain Charles Reeves of Clifton Furnace’, suggesting the place was a well-known and important focus in the area at that time.

Isaac is first described as an iron founder in an agreement, signed on 25 July 1735, between the Backbarrow Company (an established iron-making business in what was then known as Lancashire-over-the-Sands) and ‘Isaac Wilkinson of Clifton in the County of Cumberland, Founder’.6 It is a fascinating document, and makes clear immediately that the Backbarrow Company were contracting with an experienced and established craftsman. He undertakes:

… to cast for them all kinds of Cast Iron Ware whatsoever and what Quantities thereof as they may require him to cast at Backbarrow and Leighton Furnaces for the Term of Twenty One Years (and it shall not be Lawfull for him to leave the said Business during the said Term upon any account if they think fit to continue the same) at the following Rates being sound and merchantable goods viz Pots and Pans of all sizes at Two Pounds Seven Shillings and Sixpence p Tun Girdles and Boshes at One Pound Four Shillings p Tun Backs Grates and Heaters at One Pound p Tun Weights at Fifteen Shillings p Tun Waggon Wheels at One Pound Eighteen Shillings p Tun and any other kinds of Work at Proportionable rates, the said Isaac Wilkinson finding all kinds of Tools Utensills and necessaries whatsoever requisite for Casting the said Wares at his own proper Costs and Charges, the said John Maychell William Rawlinson and James Maychell finding a Casting House of Twenty Yards long and Ten Yards wide for the said purpose …

Casting house fronting a blast furnace; a familiar sight for John Wilkinson.

Isaac, then, did not learn his iron-founding skills at Backbarrow, nor did he come here as a youngster to learn his trade. He is, at this point, 40 years old with enough experience at the Clifton furnace to give him an impressive range of casting skills. Moreover, he has sufficient standing to negotiate a compensation clause in his contract should it be terminated, and from the beginning he is pushing his employers towards innovations. The contract continues:

… But in Case the said John Maychell William Rawlinson & James Maychell do find the said Business not beneficial to them then it may be Lawfull for them at any time to make void this agreement provided they employ no other Workmen afterward in the same way and do pay the said Isaac Wilkinson Fifty Poundes for full Damage and Satisfaction in procuring Toolles; And it is moreover agreed that if the said John Maychell William Rawlinson and James Maychell do incline to have the abovesaid Wares made by an Air Furnace in the Intervalls when their Blast Furnaces are out the said Isaac Wilkinson hereby covenants to build the same at his own Charge and to cast the Wares at the abovesaid rates but not to find the Fuel for that purpose …

There is another folk memory, told in the Backbarrow area, of Isaac Wilkinson being paid in part by his employers in molten metal to be used for his own purposes, and of him carrying it in pots from the furnaces across the road to moulds at his house. This has tended to be dismissed by commentators who understand the quick-cooling loss of fluidity of molten iron. Such memories become more feasible, however, in the context of this early reference to an air furnace, in which the metal could be reheated and further refined before being poured.

Information about Isaac’s subsequent work at Backbarrow comes from the account books and journals of the Backbarrow Company. They show that his early energy and drive are impressive; building of the casting house, the ‘new pothouse’, begins in December 1735 and continues through the winter.7 There is a payment against it of £45 11s 10d in February 1736, and Isaac begins casting in July even though the roof is not finally slated until September. His first quarter’s wages are paid the same month and a new account for ‘Isaac Wilkinson Potfounder’ is opened, which shows a production, by the following February, of some 60 tons of pots, pans, backs, girdles, plates and wheels.

Later that year, he proposes another innovation to his employers. He has identified a marketing opportunity for an improved type of box smoothing iron, is confident of his skill to manufacture the new product himself, is keenly aware of the competitors in the market and what must be done to outmanoeuvre them, is clear about how the release of his new irons onto the market should be controlled and of what the price should be. His written proposals are accepted with only minor modifications and signed by all parties in an agreement dated 18 October 1737.8

This document identifies Isaac Wilkinson as a skilled iron founder certainly, but also as a potential entrepreneur with imagination and business flair; qualities that, from this point on, recur throughout his life. It also outlines the unusual relationship he was able to establish with his employers, the Backbarrow Company: the company is producing iron which they sell as Bar Iron by the ton, or make into iron products (‘Cast Iron Wares’). Isaac is the skilled founder employed by them to make the cast-iron wares, for which he receives wages. But he is also allowed to sell for his own profit a proportion of the cast-iron wares he has made, under an arrangement whereby he buys back from the company for resale his own products at an agreed rate per ton of wares, the rate varying with the type of product.

For his improved box irons, for example, the rate he proposed was £12 or £13 per ton of wares, raised to £14 a ton in the agreement. He also asked his employers for sole rights for the sale of these box irons, which, since he took out a patent for that product the following year, it seems likely he was granted.9 It is the manner of the moulding of the one-piece box that makes his smoothing irons innovatory, and the fact that they can be made from a ‘melted fluid’ of ‘any mixt metal’ indicates a further use for the air furnace in which any old metal could be re-melted.10 The wording of the patent is revealing:

… my said metallick boxes, both bottom, top, sides, and the barrs within them, consist of one entire piece of any cast metall, either iron, brass, copper, bell metall, or any mixed metall, and are made and performed from a melted fluid of any of the said metalls cast into a mould invented for that purpose, and then ground and finished in the same manner as other box irons now in use.

Two interesting questions emerge at this point. First, to what extent was an iron founder, in those early days, looking towards the domestic market for his profits and as an outlet for his products? How far is his imagination and inventiveness focussed on the domestic scene? The list of Isaac Wilkinson’s cast-iron wares suggests that the domestic market was important. Pots, pans, fire backs and grates, weights and smoothing irons are listed among his products. Second, what role did his wife play in engaging his attention on the need for an improvement to the box iron then in use? Its old construction of separate plates bolted together could allow hot ash or small cinders to drop out onto the ironing. Perhaps Isaac had some personal experience of this.

From earliest times, forges and furnaces were blown by leather bellows; the smaller ones hand operated, the larger ones, as at Backbarrow, attached to a cam wheel driven by a waterwheel. Servicing and replacing the leather airbags, which became creased and worn from constant use, was a considerable recurring cost. The Backbarrow Company journals show payments for ‘tanned hides for bellows’ in December 1736 and April 1737, soon after Isaac Wilkinson arrived there.11 In the autumn of 1737, however, he changed, indefinitely, the dependence of his employers on leather bellows, in a step that at once demonstrated his imaginative flair and his iron-making skill.

The journal of the Backbarrow Company for 1737 has the following detailed entry: ‘Backbarrow Forge Dr to Acc/t of Cast Iron Wares the sum of £6- for a pair of Cylindrical Cast Iron Bellows, put up in Septemr 1737 being computed at ½ a tun and valued at £12 per Tun … £6-.’ There is evidence that the company was enthusiastic about this innovation, was prepared to support it financially and wished to celebrate its arrival, too. There are account entries, round this date, for fourteen days’ day-labourer payments at 1s a day ‘to George Walters about Iron Bellows etc’, and several transfers from one account to another of iron ‘for new Iron Bellows’. Particularly interesting, and showing beyond doubt the enthusiasm of the company for this improvement, is an entry in ‘sundry disbursements’ for September 1737: ‘For Ale ordered by the Masters on occasion of the Iron Bellows £3-.’12 It was obviously a signal event.

There are two further significant records. Firstly, on 1 October 1737: ‘By forge, for iron used about Geering the new Iron Bellows 1c. 7st. 12lbs … £1.11.9d.’13 Secondly, on 27 December the same year, when the forge was also charged ‘for a pr of cylindrical Bellows & Appurtenances’ weighing ‘18 cwt’.14 The former of these entries could relate to repairs or improvements to the first iron bellows installed, but it seems probable that the latter refers to a second pair of bellows at another hearth. Overall, it is clear that Isaac Wilkinson was using iron bellows, designed, manufactured and installed by himself, for forge and foundry work at Backbarrow in 1737 – some twenty years before they came into use elsewhere.

In this context, too, the second part of his ‘Box Iron Patent’ of 1738, which is puzzling and often ignored, begins to make sense. For he includes in it another item, which is difficult to relate to box irons, and is described as his ‘Bellows of Cast Metal for Forges, Furnaces or any other works …’15 His so-called ‘Iron Bellows Patent’ did not appear until 1757 – the date generally credited as marking the introduction of iron bellows into the iron-making industry – but that patent application is a carefully elaborated description for a ‘machine or bellows to be wrought by water or Fire Engines …’16 By that time, of course, he had two decades of practical experience of iron bellows behind him.

It is surprising that, in those intervening years, no one stepped in to steal the invention, particularly in view of the enthusiasm with which the Backbarrow Company initially adopted it, which one would expect to lead to a wider broadcasting of its use. It may be that, in spite of William Rawlinson’s contact with the Midlands iron-making world, this far outpost of Lancashire-over-the-Sands, difficult to access by road, though less so by sea, retained its isolation and integrity until the 1770s. By then, Isaac’s iron-making sons John and William were living and working in the Midlands whilst retaining strong links with their roots.

During these early Backbarrow years, Isaac’s family had not grown beyond the two boys born in Little Clifton in 1728 and 1730 respectively, John and Henry. It is as though he needed to pour all his energy into the early opportunities this new work provided. Things were about to change, however. In 1741 a daughter, Mary, was born; in 1744 a third son, William; and two further daughters, Sarah, in 1745, and Margaret, whose birth date is uncertain.

Tradition has it that Isaac lived throughout the Backbarrow years at Bare Syke, a substantial family house, gardens and orchards belonging to the Maychells, across the road and a little south of the furnace; close enough to supervise the work continuously but upwind of the furnace’s fumes. There is reference in Backbarrow documents, long after Isaac was dead, to ‘Wilkinson’s House’, which is likely to be Bare Syke. Ask after Wilkinson’s House of any old resident in Backbarrow today, and they will point you to it. The impact of the family on the place has been enduring.

Isaac’s two older boys, John and Henry, grew up at Backbarrow – youngsters of 7 and 5 when they arrived, young men of 20 and 18 when they left – and throughout their early adolescence they had no other siblings in the family to consider. It was a marvellous place for two such lads, quite apart from the fascination of the furnace and forge which Isaac would certainly involve them in as they grew older. Backbarrow lies in a gorge section of the River Leven, about a mile downstream of the point where it empties out of the foot of Lake Windermere. To this day, it is a clean river of waterfalls and pools where salmon wait, with extensive oak woods, rich in wildlife, spreading into the valley on both sides. Throughout his life, John particularly, and in stark contrast to his preoccupation with the noise, heat and smoke of his iron-making, responded to wilderness and water with a spirit that anticipated the later Romantics; he created his own corner of paradise in later years at Castle Head, not far from Backbarrow. Perhaps this is where it began, where he and Henry were free to roam, where this wildness and wet created a pattern, an ideal, for his later life.

Isaac and John at Backbarrow – an imagined picture

‘Father, Father, the gentlemen are coming, the gentlemen are coming!’

John hurtled up the cinder track towards the furnace buildings as fast as his legs would carry him. He had been sent down to the house for bread and beer and had seen the two horsemen round the bend on the riverside road, half a mile downstream.

His voice, not yet quite broken, was shrill enough for Isaac to hear above the loud breathing and groaning of the furnace, and the creaking of the wheel. He came to the wide, doorless entrance of the casting shed with a twinkle in his eye and caught his son round the shoulders as he arrived breathless.

‘Whoa lad, steady,’ he said, kindly enough. ‘What gentlemen?’

‘It’s Mr Rawlinson on the black stallion, and Mr Machell, I think …’

‘Here, put this on,’ said Isaac, handing him a heavy leather apron similar to his own. ‘And put them clogs on. We’re going to run iron. Them’ll wait.’

Father and son moved back from the sunlit doorway into the inner darkness of the shed and picked up their long-handled ladles. Five other men stood by, waiting. Isaac looked round quickly, saw that the moulds for utensils and implements they had been preparing with fine sand for the last few days were all neat and ready, noted that the sand bellies and channels were clean and smooth, and gave the signal to the man standing by the furnace with a very long probe to begin.

The man pulled a darkened glass shade down in front of his face and reached forward with his probe for the plug at the bottom of the furnace. There was a moment’s pause before he found it. Then, with a smooth movement, he withdrew the plug and stepped backwards. A thick, bright orange stream of molten iron came curving from the furnace through the channel and into the first sand belly, filling it quickly and overspilling into the narrow channels and the smaller bellies around it. John, standing beside his father and the other men, watched in wonder as the living metal slowed and became still, then changed colour as it began to cool. It drew out at his feet the image of a pot-bellied sow with her piglets feeding from her all around. It was a new creation that always thrilled him.

The man with the long probe now diverted the molten flow, to create another sow and piglets in a second set of sand channels and bellies alongside the first. When this was almost complete, he glanced at Isaac for the signal before diverting the bright metal into a large cauldron standing close by. As it began to fill, Isaac stepped forward, dipped his ladle into the cauldron and carefully carried the molten metal the few strides across the floor to pour it into the box moulds. As his ladle emptied, John came to stand beside him to continue the process.

Timing was everything to ensure a continuous flow of bright hot metal into the moulds. The orange flow from the furnace had begun to falter, and at another signal from Isaac the man with the long probe carefully placed a new bung directly into the furnace tap. As the flow ceased it became darker in the shed, the metal in the moulds now a dull red. In the bright sunlight of the casting shed doorway John saw the two gentlemen standing with the light behind them, smiling as Isaac moved towards them, taking off his apron. Then John was sprinting back to Bare Syke for the bread and beer he’d been sent for and forgotten.

Henry is a shadowy figure and virtually nothing is recorded about him. It has been suggested that he was born impaired, handicapped in some way, but this has to be speculative. He did not follow his older brother to school, despite the fact Isaac was careful and determined in the education of his children; there is no record of a marriage; and he remained within the embrace of his father’s house until he died at the age of 26.

There is one other haunting piece of evidence. Carved into a vertical face of the hard slate behind Bare Syke, and still visible in a place where Isaac is said to have espaliered his fruit trees, are the initials ‘HW 1745’ in a fine elaborated script – obviously the handiwork of a competent scribe. If Henry did this he had certainly learned to write and might have been taught within the family. Or did John inscribe it for him? What could be John’s initials ‘JW’ (possibly ‘IW’) are cut into the same face of rock close by.

It is interesting to speculate that, had Henry’s life been impaired from birth, might this not be reason enough for the eleven-year gap before the arrival of the next sibling? The more so if there had been earlier birthing tragedies. Perhaps Isaac and Mary had decided to have no more children, even before they came to Backbarrow. If so what changed that? Or was their daughter Mary a happy accident which carried them into the sunlight again? Such things would have implications for the happiness of the family and for the atmosphere in which the children grew, particularly for John who was alone with Henry for so long.

The possibility, of course, remains that John could have been the surviving son of Isaac’s deceased first wife. If his first wife, Ann, had died when John was born, and Henry was the damaged firstborn of his second wife, Mary, Isaac might have decided to have no more children. All his considerable energy would go into his iron-making. Then his daughter Mary was born and everything changed again.

In his old age, when he was living in Bristol, Isaac signed an agreement with Thomas Guest of Dowlais Furnace at Merthyr Tydfil and Thomas Whitehouse Ironmonger of the city of Bristol, for the casting and manufacture of iron goods which contains the following clause:

… it is also hereby agreed … Thos Guest and Thos Whitehouse … to pay the said Isaac Wilkinson and Mary his wife during their natural lives one shilling per ton for every ton of Iron … made at the said works from coakes over and above 15 tons per week on average through the Blast …17

…The underlining is mine. It is not, of course, proof that a first wife died in those early years. It does establish that in his old age Isaac had a wife called Mary, and, if the Workington church record identifies the same Isaac, then the Ann named there as his wife must have been dead. It supports the possibility that John’s natural mother might have died when he was very young, that he was brought up by a stepmother, that William – with whom he quarrelled bitterly and irreconcilably in his later life – was his stepbrother, and that his closeness to Henry might simply have been a matter of their closeness in age.

In those later Backbarrow years, John left Henry to go to school. Though at precisely what age is uncertain, and since Isaac sent him to a Non-conformist school at Kendal, it is likely Isaac and the family were known dissenters by this time. The church schools, and there were few others then, simply would not be available to them, so they were fortunate in having a good school run by a remarkable man close by.

The Reverend Caleb Rotherham was associated with the Unitarian Academy at Kendal from its inception in 1733, until his death in 1752. On 27 May 1743 he was admitted Master of Arts of the University of Edinburgh, followed immediately by a DD (Doctor of Divinity), awarded on public disputation ‘On the Evidences of the Christian Religion’.18 His academy, however, was not a theological academy, and two-thirds of his students were never intended for the Ministry. It was a place for young men, as opposed to boys. He charged 8 guineas a year for lodging and board, and 4 guineas for learning. The young men were required to provide their own fire and candles and wash their own linen: ‘They go through a whole course of Mathematics … I have a distinct consideration for that branch of instruction …’19

Outside the universities of the time, which, as with Church establishments, would be closed to him, it was probably the best education available to Isaac’s sons. Because of the building and engineering demands inherent in the iron-making processes, Isaac would recognise the value of a good grounding in mathematics. There is plenty of evidence in John’s later life that it served him well, and that his handwriting and use of language had also benefited.

He, though never Henry, is in a list of Caleb Rotherham’s students, which has been dated at c. 1745 as a consequence of other names included in it. The precise dates of John’s education at the academy are not known, though since he would be 18 years old in 1745, that list was likely to have been drawn up towards the end of his time there. It is recorded that Isaac later sent his son William to school at the Warrington Academy when he was 14 years old, so it is reasonable to suppose John started at the same age and spent four years at Kendal.

Two other young men at the Kendal academy about this time were James and Robert Nicholson, sons of Liverpool merchant Matthew Nicholson, who was himself cousin to Edward Blackstone, one of the original founders of the Unitarian Chapel in Kendal. His widow, Ann, married Caleb Rotherham in 1746, after the death of his first wife. Matthew Nicholson, with his Kendal links, may therefore be the ‘respectable merchant’ to whom John was said to be apprenticed on his return from school, ‘and with him continued about five years …’20

In 1740, when he would have been considering the education of his eldest son, Isaac was spending more time at Leighton furnace, also owned by the Backbarrow Company, where he began casting and trying guns. How far this was driven by an urge to continually push out the horizons of his work, or by his employers’ belief that there may be good profits in it, is difficult to assess. There is, however, evidence of restlessness in Isaac’s life at this time, and also the first signs of differences of opinion with the company.

On 2 February 1741, shortly before the birth of his daughter Mary, Isaac signed a lease with James Machell for a run-down corn mill and kiln on the east side of Backbarrow Bridge, and a dwelling house with outhouses, orchards and gardens on the west side.21 Bare Syke is on the west side and the description of the property fits, though there is a discrepancy in precise location. Does this mean that Isaac, up until this point, had held his family house by grace and favour until this lease gave him occupancy as a tenant? And if so, was it a move by the astute Isaac towards greater security? Or is the dwelling house in the lease another property, which, since he was living at Bare Syke, he subsequently sub-let? Certainly by 1753, when Isaac sought to terminate this lease, one ‘Widow Taylor’ was living there, but by that time he had been gone from Backbarrow for five years.

The corn mill was fitted out with new grindstones, suggesting he used it to finish the cast-iron wares like box smoothing irons, which he sold on his own behalf, providing him, at the same time, with his own commercial premises. If disagreements were beginning to emerge with his employers, this would be important.

The casting of guns was not going well. The accounts show occasional, rather than regular, evidence of the purchase of gunpowder ‘for trying of cast guns’,22 some of which burst on proving.23 There is also an increasing tension between William Rawlinson and the other partners at this time. William Rawlinson had been Isaac’s chief support in the Backbarrow Company, certainly for the widespread sale and distribution of his cast-iron wares, and may have been responsible for the ill-starred sortie into gun manufacture. By 1743 the partners had had enough. In a new agreement with Isaac, dated 14 March, there are indications that a substantial conflict is being resolved:

Let it be remember’d that Backbarrow Company having sundry articles under Consideration relating to Isaac Wilkinson … and have concluded & agreed with him as followeth, viz That Damage which the Company have suffered by Casting of Guns, shall be Ballanced by the workmanship of Casting Hammers & Anvills at Leighton last Blast, so that all Demends on both sides in these respects are to cease and be evened …24

‘Let it be remember’d’ has an admonitory tone, which is significant, and it would be fascinating to know what these ‘sundry articles under consideration’ were and whether William Rawlinson stood beside Isaac at this time. The future involvement of each of them in the Backbarrow Company was to be short-lived. A statement of William Rawlinson’s alleged debts to the company, amounting to £3,369, was drawn up by the manager in February 1747. A counter-claim by Rawlinson demanded the production of the accounts and the sale of stock to meet the company’s debts to him, and the dispute was only settled when the Machells undertook to buy out William Rawlinson’s moiety in the company in an agreement dated 8 April 1749.25

By this time, Isaac Wilkinson had gone. Following the new agreement of March 1743, the journals continue to show an Isaac Wilkinson account with the company each year until 1748, but in 1747 a major dispute erupts. By now, Isaac is in partnership with William Rawlinson’s brother, Job, and two other men in a new iron-making venture, the Lowood Company, about 1 mile down-river from the Backbarrow works and potentially a serious competitor to it. Isaac was still bound to the Backbarrow Company by his 1735 contract, and they went so far as to obtain lawyers’ opinion as to whether he was still in their employ and could legally do this. They were advised that, provided he continued to work for them, there were no grounds for legal action against him, but the end was in sight. His account with the company was drawn up and balanced to 25 March 1748; after twelve years of continuous business his name appears no more in the registers of the Backbarrow Company.

Map showing the location of Rigmaden.

The terms under which he was released from the 1735 contract ahead of the twenty-one years he was required to serve, are not known. Fell, who obviously had access to primary sources now lost,26 tells us that Isaac and the other original partners in the Lowood Company disposed of their interest to two local men in 1749, and there is some later evidence to support this.27 The Backbarrow years, consequently, came to an end in 1748, at which point Isaac Wilkinson and his family moved some 5 miles south-east to Wilson House, near Castle Head Hill beside the River Winster.