8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

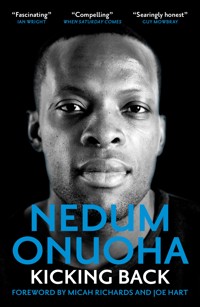

"A searingly honest account … Nedum tells it like he played, with nothing left out." – Guy Mowbray, Match of the Day "A frank, thought-provoking and compelling insight into one of football's most articulate voices." – Rory Smith, New York Times chief soccer correspondent "Nedum Onuoha's autobiography is considerably more compelling than most of those by more decorated players." – When Saturday Comes *** Nedum Onuoha was not a typical footballer. Picked by the Manchester City Academy aged ten, he was determined to continue his education despite the lure of a career under the floodlights. Fiercely intelligent on and off the pitch, Onuoha developed into a talented defender and played his part in City's meteoric rise. In this characteristically forthright book, Onuoha reveals what goes on behind the scenes at top-tier clubs. Stuffed with insights into household names like Stuart Pearce, Sven-Göran Eriksson, Roberto Mancini and Harry Redknapp, this is football and its most famous figures as you've never seen them before. Kicking Back is also the story of one man's search for identity: as a footballer, as a black man in England and as an outsider in the US during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. What is it like to receive horrific racist abuse while doing your job? And how has football failed the black community? Onuoha provides a damning assessment of the sport's authorities as he dives deep into a life spent on the pitch.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

iii

v

This book is dedicated to my family and close friends for supporting me through all of life’s adventures

Contents

Foreword

‘Sorry, what? You want stories about Nedum? Deary, deary, deary me. He’s the most boring man in history!’

Then the cackle. The one that is contractually obliged to follow each sentence Micah Richards utters. Three minutes later, he’s joined on the Zoom call by Joe Hart.

‘Hart-dog! What’s happening!’

‘Sorry I’m late. Been at the butcher’s getting my dinner.’

The laugh again.

‘What’s going on?’ Joe seems equally unimpressed with the task ahead. ‘Everyone’s selling out! What’s Nedum’s book even about?’

‘He’ll be putting the world to rights, won’t he.’

‘Oh, he’ll love it. Absolutely love the fact his opinion might poke people. But I guarantee it will also make them think.’

• • •

I played alongside Micah and Joe for both Manchester City and the England Under-21s. For reasons that immediately became xquestionable, I left them alone to have a conversation about me…

• • •

MR: I don’t know why he’s asked me to do this. When he was the main man at City and he got a little injury, I leapt in and took his place in the team!

JH: I think that speaks more about him, Meeks. He’s not looking for a big-up. He’s looking for honest people. I’d like to think we’re not here to say he’s an amazing guy or a great player.

MR: True. He was class, though. When we were growing up, he was playing two or three years higher than his age group at the City academy. We called him ‘Chief’, because he was the No. 1 guy, but back in the day he was a striker. He used to bang goals in left, right and centre. He was just quicker and stronger than everyone and actually had decent technique. I’m not even joking!

JH: That’s kids’ football, though, isn’t it? He likes to think it didn’t change, but it did. If he’s being truthful, he knows that I could dominate him if he was going against me. With all the intellectual standing he had, when I was in goal against him, I could mess with him so bad. He was mine. He was a toy, and continues to be, because I know that he brings it up all the time. So, I can confirm that he couldn’t score to save his life in training.

MR: But I don’t understand, honestly, Harty, because when he was younger he used to just run past a defender, drop his shoulder and smash it into the top corner! I thought this guy was going to be ridiculous. Now, though, I play five-a-side with him and he’s got one of the worst techniques in the history of shooting! On the xiball, he’s so awkward! All that talent for scoring goals he had at a young age; I don’t know what happened to him. It just went!

JH: I did love playing with Nedum, though.

MR: Once he got a bit bigger and he was moved to the back, he was just so good. He was incredible, and I thought he was going to be the next Sol Campbell. He had it all: one-on-one defending, tactical nous, talking with his teammates and leadership. I’m telling you, the next Sol Campbell. I know it’ll hurt him that it didn’t work out that way, but the problem was he didn’t actually do anything wrong. He was just injured at the wrong time and then Roberto Mancini didn’t give him a chance at City. He was so unlucky, and that’s really being honest about the situation. He was just really unlucky.

JH: The most important thing for me is that I trust those defensive players ahead of me as a footballer and as a person. I trusted him, and he trusted me. That’s the best feeling ever for me as a goalkeeper. I knew nobody would get past him easily, and if they did sneak through he had the ability to deal with it. He was very honest in his communication, and I’m a big communicator too, so we worked well.

MR: He could have been better at jumping. I’m all arms everywhere when I’m going up for a header, but he was too nice!

JH: And sensible. He certainly wouldn’t party like you and me, Meeks! His fun was different, but we always respected that because we saw his thought process. Whether he was on a night out or not, he had a real good balance. It’s not easy to both play and party and it can leave people by the wayside, but it was really good for others to look at Nedum to realise you don’t have to try to be a rockstar. I first met him when I was still at Shrewsbury xiiTown, but the sportswear company Umbro had taken a punt on me. Nedum was pretty much Mr Umbro at the time, and I found him quite intimidating with his big frame and deep voice. I was nervous because I was starting to roll in Premier League circles, but I was still a League Two player. I didn’t really expect people to have any idea who I was, but Nedum immediately put me at ease. That strikes me about him, you know, that he has an ability that I really like in someone, and that’s to dictate the mood of a room. He took the time to get to know me, and I saw that as a huge quality. I was being linked with Manchester City at that point, so maybe in a way he was just tapping me up! Then when I joined the club, I could tell that everyone kind of understood him. And he might have been the geeky one of the group, but you couldn’t mess with Nedum!

MR: I think the turning point in Nedum’s career was when he was playing brilliantly under Mark Hughes in 2009. All the fans were singing, ‘Nedum for England!’ I’d been in the team but got injured, and this time Nedum replaced me. He was incredible for the rest of that season. I started sweating, thinking I wouldn’t get my place back! But I desperately hoped he would get an England call-up.

JH: We all wanted that for him.

MR: There are two ways of finding out when you’ve been picked for England. You sometimes get a text, but you always get a letter. We were going out to reception at Carrington, and he hadn’t received a text but there was a letter waiting for him. His form had been so good he would have been excited to read it, but it was another call-up to the Under-21s, not to the senior team. I think that was demoralising for him because if he didn’t get his England chance then, he was never going to get it, because he xiiicouldn’t have done any more, or played any better. He was even playing ahead of me! But then Mancini came, and it was another case of bad timing.

JH: It’s about managers, and sometimes it’s about moments. When I met him, he was the kind of person who had it all figured out. The pathway was there. But when you get to the very top it doesn’t really matter how good you are, because everyone’s good. It can fall apart pretty quickly, and when it did for Nedum at City, it wasn’t through any fault of his own. He had some big decisions to make about how he was going to behave as a person, and he took the high road. We expected it, because of the man that we knew, but it’s not easy to do. It hardened him and left a lot less room for bulls**t.

MR: Joe, how many times have I rung you over the last fifteen years, whether I’ve been doing well or badly? I’ve opened up about certain things with you, and with Nedum too. But he never really does the same. I think he wants to be the one who can solve the problem, because honestly, he’s like a brainiac.

JH: I get the impression he likes a crisis because it means that he can help people. There were countless difficult dressing rooms at QPR, for example, and I think it actually suited his character. Them making him captain was the best thing they ever did. He’s good at dealing with carnage!

MR: It’s interesting that he’s written a book, because he normally doesn’t like to reveal what’s going on his life away from football. Even when he was going through what he did with his mum. How are you supposed to deal with that? I would text him and ask if he was all right, and he’d just say, yeah and that he wasn’t worried. He can’t have been OK, but he felt like he had to show that he was in control of every situation. Some people might think that’s xiva positive thing, and I know men aren’t great at talking to each other, but it can’t have been good for his mental health.

JH: He was very forward with us about some things, like Joey Barton or Roberto Mancini, but I think he’s been hurt more than he ever thought he would, and that’s a heavy burden.

MR: I just feel like he took too much in, Joe. We’re all human, no matter what. I like to think that he would have been able to reach out to us more if he had been genuinely struggling. What he’s been through is tough. Like, the guy couldn’t catch a break, and a lot of it is my fault! When we were fighting for the same position in the team, he went away with the England Under-21s and scored, but the following night I got my only goal for the senior team. I stole the glory only twenty-four hours later!

JH: Why didn’t you just leave him alone!

MR: But then Pablo Zabaleta did it to me! The biggest game of all our careers – the last day of the season in 2012 – Pablo scored the first goal for Manchester City against QPR. It could have been anyone, but it was him. It was like a dagger to me as I sat on the bench, and it must have been a bit like how Nedum had felt with me. That’s just life, isn’t it? Wrong place, wrong time is somebody else’s right place, right time.

JH: I’ll never forget that Under-21s goal you mentioned. It was in Montenegro. That was the night, when he and I were together in the tunnel, that he was racially abused by armed guards. I just knew I had to stay with him and back him up whatever. I didn’t know what to do, but I wanted Nedum to know I was 100 per cent behind him. It wasn’t like we were on the street; we were grown men, so I’m not sure we’d start swinging, but we could at least have tried to reason with them. This was like a stand-off, but there were more of them and they had guns.xv

MR: He was so young at the time, still just trying to figure stuff out. He would have felt so powerless. I’ve changed now and my brain’s programmed differently, but I would have probably got shot if I was there. I would have been aggressive.

JH: It was strange, and it still feels weird talking about it now. I’d love to have done something about it, though. Not in terms of fighting because you can’t beat six guys up, but why didn’t we even think to report it?

MR: There’s only so much you can do. Those guards are gone. It’s not that I don’t care, but it doesn’t affect me any more: they’re the kind of people that if they’re going to be racist then let them. They’re doing that to Nedum for a reaction, so they can shoot him or baton him. I’m now more worried about the root of the problem. If someone’s brought up in a racist family, can you blame them for being racist? I think you’ve got to look at the bigger picture and educate that son or daughter while they’re still young. You can help the people who want to learn, but with those who don’t you’ve got no chance. It doesn’t matter what you say. And I know that sounds bad, but it’s just the truth.

JH: Nedum would have a good go at convincing anyone, though.

MR: He’s just so intelligent! Football people normally only care about football, but Nedum knows everything about everything.

JH: You’d go the whole hog if you got involved in an argument with him, especially if you were going to dare to challenge what he was saying. You’d be stuck there for hours as he subjected you to long words and his dedication of proving just how right he was!

MR: The thing with Nedum is that there’s no point arguing because you’re not going to win. You could have a valid point, xviHarty, but he’d spin it on its head and make you see it from a completely different angle. By the end of it you’re agreeing with what he’s saying!

JH: He’s a tough one to get into a chess match with.

MR: ‘Shut up, Chief. We know you’re a genius.’

JH: ‘OK, you win.’

MR: ‘Yeah. Well done.’

JH: He’s a special character and a special guy, but he does love the sound of his own voice. And he pretends he doesn’t! Is there going to be an audiobook? Because if there is, he’ll have to read it.

MR: I’ll always help Nedum out, but apart from Biff and Chip when I was younger, I’ve never read a book.

JH: Oh, come on, Meeks, you’re better than that.

MR: Anyone from my old teams, I’ll give them my full support. 100 per cent.

JH: So, are you going to read the book?

MR: I’ll listen to the audiobook. But that’s it.

Introduction: neɪdju:m ɒnu:əʊhə

‘What’s your name?’

‘Nedum Onuoha.’

There’s a silence. I’m thinking, here we go.

‘How would you spell that then?’

I then proceed to spell it out, always the same way. Every time.

‘It’s Nedum. That’s N–E–D–U–M for mother.’

Then I pause, so that they know it’s now time for my second name.

‘Onuoha. That’s O–N for November–U–O–H–A. Onuoha.’

Then there’s another silence, during which I start to think to myself, I wonder if they actually wrote that down? Many times before I’ve spelled it out to someone just like that, and then the correspondence arrives with my name split into three, or with extra letters put in. I’ve had Ohuoha, or Ohuona, or versions where the ‘O’ is swapped with the ‘U’, because it might feel more natural for them to say it like that.

This happens literally every time I’m on the phone. I’ve reached a point in my life where I now expect people not to 2listen to me when I tell them how my name is said and how it is spelled. And that’s a really weird position to be in. Every day I wonder if I should make a bigger deal of it. I’ve heard people be mocked for not being able to say Murphy or Jones or names like that. Yet, still, here I am. Instead of others being mocked for not being able to say my name, I’m being mocked for having a name people can’t say. Nobody’s around to fight that battle for me, so, as is the case with most things, you end up accepting it.

I always introduce myself as Nedum, but my full name is Chinedum. I was born in Nigeria to Nigerian parents, and all my direct bloodline is Nigerian. Amongst Nigerians, I would be called Chinedum, because it has meaning within the culture of the Igbo, the tribe I’m in. In their language, Chi means God. I’m Chinedum; my older sister is Chioma (we call her Diuto); and my younger sisters are Chidinma (Chidi) and Chiamaka. Chinedum means ‘God guides me’, so that’s why they don’t simplify it in Nigeria, where faith and family mean everything. I’m not embarrassed by my name. I never have been, even though in the past I didn’t wear it like a badge of honour as I probably do now. I was always proud of it, but it’s mattered more to me since I became a father in 2014, and my three kids all have Igbo middle names, which my dad helped me with, because it attaches them to their history. Our history.

My family moved to the UK when I was five. Even in Nigeria my parents had always called me Nedum, but they wanted to make it easier for people in their new home to understand, particularly as they wouldn’t have realised the significance of the ‘Chi’ part anyway. I never asked them if I could change from Nedum, and I have no middle name to use instead, as my father had decided to when we arrived in the UK. I remember when I 3was in primary school there was a spell when I really wanted to be called Denzel. I’m not sure why, as I was too young to have watched anything with Denzel Washington in, but I was obsessed with the name, and I used to write Denzel on my schoolwork, even though I knew that I didn’t really want to change it permanently. Neither my family nor the school were up for participating, so I wasn’t able to do it for long. My identity was essentially wherever I was at any particular moment. If I was in school, I wanted to fit in at school; if I was at training, I’d want to fit in with people at training. Now I think being different is more a strength than a weakness.

However, I have on occasion during my adult life also changed my name by choice. In Starbucks, trying to tell a barista your name is Nedum is like talking to a brick wall. They’re going to write whatever they want on my cup. So, I’ll call myself Nathan. Surely everybody knows a Nathan, or at least recognises the name. The downside is when they shout for a Nathan and you’ve forgotten that’s you. So, even when you try to change your name to fit in, you don’t hold it in the same way you should because it’s not your identity. I understand there might be a natural British embarrassment about not wanting to offend, but I live in Manchester, an incredibly diverse city. I don’t see why people freak out when they see something different, when ultimately that sense of difference exists all around us in a multicultural society.

Or you could be waiting at the doctor’s surgery, and you know it won’t be long until you’re called from the waiting room. Mrs Murphy and Mr Jones arrived just before you, and they’ve gone through. Then the intercom clicks, ready to call up the next patient. You can hear the intake of breath, and instead of saying your name they let the breath out. You can’t see it, but 4you can sense the confusion. A few second later, they try again. ‘Err… Mr…?’ They don’t need to finish, because that’s the exact moment I realise I’m next. They’re looking at a series of letters, and they don’t know how to say them. They can continue in one of two ways. Some people try, and the ones I appreciate the most are those who do, fail, apologise, then ask me how they’re supposed to say it. Then there are others who, when I point out they’ve said it wrong, assume it doesn’t matter as I knew they were talking about me anyway. They might not care about getting it right, and I accept that people think my name is different, but it’s my identity, so surely it does matter? Sometimes it stresses me out a bit, but what can you do? You can’t start an argument with somebody to prove they’re wrong when they don’t care about being wrong in the first place. Getting into a debate with somebody who doesn’t care doesn’t work. If it happens to my father, he makes them care by flipping the tables on them, deliberately getting their name wrong and often finding that they struggle to deal with it. When it’s you, you notice.

Some of the people who know me best have never called me Nedum, not once. When I started my career, I made every endeavour to introduce myself in a proper manner, but within the world of football you tend to be spoken about more times than you will introduce yourself. From the moment somebody says this is your name, it spreads, and that is your name. You never have control of it. So, until I went to play in the USA in 2018, I was known in football as Chief. Most people I played with would call me Chief over Nedum Onuoha, because it became clear that saying Nedum Onuoha was hard. I’ve never once introduced myself to anyone as Chief. The first person to call me that was Manchester City Academy coach Alex Gibson in my Under-17s 5year. One day at Platt Lane, I remember he had a huge smile on his face when he said, ‘You know what, I’m going to call you Chief. Yeah, you’re the Chief.’ It felt like Alex had a great sense of pride in calling me that, and I don’t think he did so with a racial or tribal mindset, and I didn’t and still don’t take it that way. He had no idea that it’s a word that fits so well with my history and in Igbo culture is a compliment. It was a stroke of luck on his part, but for him mostly about convenience. He didn’t want to have to look at the five letters in my first name and six in my surname and try to figure out how to say it. It made it easier for people to talk about me. Little did he know the impact it would have over the course of the next fourteen years. The people in the academy knew me as Chief: the reserve team manager, the first teamers, they all ended up calling me Chief. As did those at both Sunderland and QPR. I would be introduced as Chief, to the extent that there were probably people along the way who didn’t know what my actual name was, and certainly not how to say it.

Hundreds of people throughout my career knew me as Chief, despite me never once using that name myself. I had no control over it and didn’t choose it, but it stuck, and I only escaped it when I went to America. There, I could be whatever I wanted to be. In the US, players don’t necessarily know every single Premier League player like those in the UK might do. They tend only to watch the bigger games from the bigger teams, so someone could have spent the whole season playing for a club in the bottom half of the table, for example, and then arrive at a Major League Soccer team to people not knowing who they are. I could shape my own identity, and I loved that. By the end of my time in America, a lot of the people I had met and worked with really looked up to me for the way I carried myself and 6the way I played; they trusted me. It was really exciting to go over there, and I walked with my shoulders back knowing that I could choose to be whoever I wanted to be. And I chose to be a good guy, so that helps!

• • •

When Alex Gibson first called me Chief, I was a striker and had already done my GCSEs. I’d got into Hulme Grammar School in Oldham after passing their 11+ exam a year early, so for me it was a 10+. I remember taking the Manchester Grammar School entrance exam too, but I didn’t get in, so after Year 5 of primary school I went straight to Year 7 at Hulme. I didn’t have the same background as most of the kids there; when I first joined there were only two black boys and we were both in the same class, so it’s fair to say I was different. Although I stood out, there weren’t any barriers to me fitting in or speaking to whoever I wanted. Because it was a private school, I wasn’t the brainiest person there; I might have been in tier two, or at least middle of the range. So, even though I was at the Manchester City Academy and maybe in the top 1 per cent in the country in that way, at school I was the median.

There were certain days when I’d take the bus straight to the academy from school. While others might have been driven from home or had a chance to get changed, I turned up in my blazer, looking just that little bit different. But at least the academy was nothing like a school playground. I wasn’t always the biggest guy, but I was one of the quickest; I was strong, and I’ve got tons of pictures from that time which show I was very athletic, but at that age everyone’s skinny. I wasn’t imposing, 7not visually stronger than everybody else, and when you’re at a football academy there’s no time to bully because you only train twice a week and play once at the weekend. It’s nowhere near as hostile as when you see somebody every single day.

Also, I wasn’t isolated as the only clever one. Two of the best players in that set-up were Nathan and Jonathan D’Laryea, who are still two of my closest friends to this day. They went to Stretford Grammar and both are teachers now. They were very intelligent, and therefore a bit different too, so I wasn’t by myself. I was never a million miles away from fitting in because it was a good group of people, very honest and humble. We were mostly Mancunian kids, and everyone was happy to be there playing together.

I changed from being a striker to a defender when I was sixteen. It was becoming clear I had the physical attributes needed to be a centre back, but I think it was just as much my intelligence that helped me succeed in that position. There is an assumption made about young black football players – whether they’re defenders or strikers – that they’re fast and strong and that’s it. It’s a shame it’s like that, because it’s a stereotype that sticks. When you’re a young player and people haven’t seen you play 100 games, there’s no real significant data on you, so in describing you people go for the things they can see straight away. Young and black equals fast and strong. But some of the things that make a really good defender, for example, won’t be noticed unless someone has pointed them out first. How would you realise that a player you’ve never seen before reads the game well or has good positional awareness while they’re also running fast? Making assumptions like this is reductive and often based on a player’s ethnicity. The same happens if you’re a black striker. 8We’ve seen for years that if someone like me is playing up front and they score a lot by running through on goal, people will say, ‘Look at the way he holds the ball up,’ or ‘Look at how quick he was running on to that pass.’ They might be a really good finisher, but it’ll be said that they’re getting those chances because they’re quick. The opposite is true of a No. 10: everyone wants to talk about their technique. For them, physical attributes are a bonus, not an expectation. But if you’re a No. 9 or a centre back and you’re black, the technical element isn’t spoken about.

I was physically strong and could play men’s football at the age of seventeen. I was quick too. I could do all that stuff, but one of my strengths was my ability to read the game. I used to think about the game in a different manner to other people because, like at school, I enjoyed taking in all the information that was available to me. That’s why I didn’t get many yellow cards for diving in during my career. I don’t think other people took the time to consider the strengths of my game, but I did, and my teammates didn’t just trust me to run fast, they trusted me to stop the ball going in the goal, which requires a bit of intelligence.

There are foundations of defending, which in its simplest form is about winning headers, making tackles and winning duels – but only after you prove you can do those things will someone say you’re intelligent or can read the game well. It’s a bonus, not an expectation, and when I was starting my career my good judgement was never mentioned. I think that was partly because of my race and partly because back then football wasn’t viewed in the same manner – most of the opinions were coming from inside the stadium, where people didn’t necessarily know the ins and outs of the game. There’s the potential for a greater 9level of understanding today because the level of analysis is very different. It used to be that you’d get your feel for football just from Match of the Day. Now, you can seek it out wherever you want, from somewhere very in-depth like The Athletic to YouTube channels that say, ‘Man kick ball down channel, was good ball…’

There was one player who escaped this institutional stereotype: Rio Ferdinand. He was always spoken about as somebody who reads the game really well, although he was the exception not the rule. Playing for Manchester United, he was able to display these qualities because at that time there wasn’t as much defending to do as at almost every other club. But imagine any player like him, starting their career five years earlier and playing for a different team, being described as looking great because he reads the game well. They’d say someone looks great because he can head it and kick it.

People making assumptions about a player based on their race is something some footballers have to deal with, but the perceived lack of intelligence is a cliché all footballers have to deal with. My education helped me to read the game. Football can be simplified to being about taking instruction and learning. I was somebody who was trying to learn about the game, to learn how things work, and I felt like it was easy for me to do that because I’d spent pretty much the rest of my life being given tasks and trying to figure stuff out. I could recognise how a striker was going to shoot, recognise where the runs in behind would come from and understand where I needed to be to stop them. I wasn’t just out there living in the moment, staring at a ball and chasing it around. Being somebody who would be described as a critical thinker did help me develop as a player. Having said that, the other side of that coin is that when things aren’t going 10well you can overthink it. I would know if a goal was my fault, even if that was based on something I did two minutes earlier. That’s when intelligence doesn’t necessarily help you. Some players might not think about the game too deeply, and for them it’s just a moment they’re able to brush off. They carry on without realising how they might have negatively affected something; I find it hard to move on.

My identity is built on conflicts, and I’m proud of who I am. I understood I was different when I was younger, but even then I didn’t necessarily want it to be seen as a weakness, and I tried to fit in wherever I could. Maybe I shouldn’t have accepted certain things and certain names I was called. But I learned. I learned about football, and I learned at school. And once you figure something out, it’s great. I’ll have conversations with anybody about anything, and I’m more than happy to say, I don’t know the answer, but next time we speak I guarantee you that I will. During my A-Levels at Xaverian College in Manchester, I was told by a teacher that whatever grade I got for my business studies AS-Level, I could expect to get a grade less for A2. I told them that couldn’t be true, but they insisted. So, I dedicated the next year to really understanding how the subject worked, figuring out how people were awarded marks in exams and doing past papers. I’m somebody who does everything possible and reads everything possible to learn as much as possible. I got a B for AS-Level and an A for A2.

I don’t go in half-hearted with anything. If I want to get better at something, I’m all-in. That was true of playing football but also of learning about my place in society. Growing up, I tried to balance my sense of identity with my desire to fit in. Now, though, I’m at a point where I feel my identity is my strength, 11in terms of both who I was as a footballer and who I am as a human. It means I can talk about different perspectives, and my education helps me to look at these things more objectively, taking in as much detail as possible. I’ve seen a lot of stuff – some good, some bad – and it’s helped me mould who I am today. I think I’m a good person, and I value my life. All I want to do now is add more value by being myself, not someone else. Everything you’re about to read about my upbringing, my family and friends and my football career in England and the US is from a person who feels like he can walk through the rest of his life with something to say.

So why not kickback with Nedum?* That’s Nedum, N–E–D…

*Kickback with Nedum is available wherever you get your podcasts.

Chapter 1

Just like the end of every weekday, Chidi and I left Miles Platting Junior School and turned right down James Street. Then it was a left onto Varley Street, where the Degussa Mill was on your right-hand side. Next, we had a choice: we could have taken the slightly shorter route through the park – but we didn’t want to run into Buster, the Alsatian that would always chase us (I don’t like dogs even now). So, we kept to the main roads, crossing over the towpath and then taking a left onto Bradford Road. We lived at 391.

I’d taken two steps into the house, thinking Dad was home, when I heard voices. I walked upstairs: there were two strangers in my parents’ room. I panicked and ran downstairs. ‘Chidi! We’re being robbed!’

Giving my younger sister no chance to respond, I ran out of the front door while she hid behind the sofa. The men must have been desperate, because when they heard us they escaped through the back door. They didn’t take anything. Guided by more sinister intentions they could have taken my sister or me, 14but our arrival home had scared them off. They had run away from two children under the age of ten.

My heart was beating out of my chest when I walked back into the house and saw Chidi still inside. I was supposed to have taken her with me. For the next hour and a half the two of us waited for Mum and Dad to come home. It didn’t occur to me that we should dial 999 because we were just kids and we didn’t make phone calls, and I’m not sure I knew where the phone was anyway. And what would they have done? The police around there were used to that type of thing. We just had to wait for our dad to phone them when he got back. The next day, it was business as usual. It had to be. The same walk to school and back: James Street, Varley Street, avoid Buster, the towpath, Bradford Road all the way to 391.

This wasn’t the first time someone had broken into our home. Even our neighbours had robbed us before. This, though, was the only occasion I’d walked in on it taking place. I was nine and Chidi was six, and maybe it’s a good thing it happened when we were that young, because thinking about it now is terrifying. Once you’ve stepped inside your house to witness someone who is not welcome, it never feels the same again. It’s the same building, and you can change the locks, strengthen the doors, even get 24-hour security if you want, but after you’ve been burgled you never get that sense of safety you once had. Every time you put the key in the door, you’re almost expecting to see someone who shouldn’t be there on the other side. Being nine, I turned the key without fear after a day or two, but as I got older and began to understand the world better, it started to return. What would have happened if those men had realised it was just two young children who were entering the house? Maybe next time 15they’ll come a bit earlier or see the value in kidnapping or hurting one of us.

Today, I still feel the guilt I experienced when I saw Chidi hiding by the sofa. I was a child, but I was in charge of Chidi, and I had left her behind. It was a fight-or-flight situation, and because I had only my fear within me I didn’t stay and fight for my sister. From that point and through lots of other events in my life, I’ve grown to realise there’s more going on than just what you see through your own eyes. I was responsible for Chidi, and something could have gone seriously wrong because of my actions. If it had, I might have been too young to really understand the depth of it then, but now the thought of it is horrifying to me. So, nobody in a crisis gets left behind, and you do what you can to help everyone, not just yourself. Fight, not flight. 391 Bradford Road taught me that.

It was our first house in the UK, and it was not in great shape. It was the best we could do in that moment, but no family our size would ever have wanted to live there. It was a council house that required some work: there was mould on the walls and once even slugs crawling on the floor. Later, on our last night there, we slept just on mattresses because our beds had already been dismantled, and our heads were right next to the slugs. It wasn’t great, but we made do.

We had moved there from Nigeria when I was five. Our previous home was in Warri, in the south of that country, on an estate for Delta Steel workers called ‘Camp Extension Delta Steel Township’. Both my parents had jobs at the company; my mum, Anthonia, was a water microbiologist, and my dad, who was then using his first name – Enyinnaya – was a metallurgical engineer. I don’t remember a lot about growing up in Nigeria 16and where we lived, but I do have the sense that we were reasonably comfortable. We had a maid, which was not something every family would have. I was born on 12 November 1986, just a year after my sister Diuto. I remember Diuto being taller than me for a significant part of my childhood, when she was basically my carer, both in Nigeria and then those first years in the UK. She was a very considerate sister who would try to look after me, even though there was so little difference between us in age, and Chidi too. She took on the role of mother when ours wasn’t there, making food and making sure we didn’t behave like demons. A figure in my mum’s image.

Diuto needed to step up because my mother was the first of the family to leave Nigeria for the UK, to study for a PhD in environmental sciences at the University of Salford. Both my parents worked incredibly hard at their education, and even though I wouldn’t claim they were gifted or that things came naturally to them, they were very successful. It wouldn’t have surprised many people that in 1990, at the age of thirty-one, Mum moved to a different country to invest more time into her education. The next year, Diuto, Chidi and I all joined her in her new home just north-east of Manchester city centre, where Dad would join us nine months later. Five of us all in that little house in Miles Platting.

Adjusting to our new home was made easier by the fact we’d spoken English in Nigeria – it’s the national language there, even though the Igbo tribe to which my family belongs has their own language too. There are about 300 ethnic tribes in Nigeria, a country with more than 200 million people, and each has their own language. The differences mean that one tribe doesn’t necessarily understand another (which blows my mind when I think 17about it), so they are united by English. In Nigeria, your tribe is your backstory, your language the nuance to your identity, but being Nigerian of any tribe was enough to bring together those who’d moved to the UK. Even though they’d chosen to leave their home, my parents welcomed the familiarity that other Nigerians in Manchester provided, and they were drawn to one another, particularly as it helped them to get through some tough times.

My parents did bring a little bit of Igbo culture with them, retaining some of the simple words and phrases they’d used with us in Nigeria, but we didn’t have any conversations using the Igbo language once we’d moved because it wasn’t something that was going to benefit day-to-day life. It is likely that had I stayed in Nigeria I would have followed the same path as everyone else there in embracing the culture more, but it was more important for my parents to learn how it all worked in England. There was no back and forth, and I couldn’t tell you the Igbo words for anything like ‘knife’ or ‘dish’ or whatever, but you’d often hear greetings and endearing terms in the tribe’s language: ‘Kedụ’ means hello. Dad might say ‘oliạ’ as an alternative: how are you doing? Then you’d respond with ‘Ọ di mu mma’: I’m well. They’d say ‘ka chi foo’ for goodnight. ‘Biko’ is please. Mum might use the nickname ‘bobo’ for me, or ‘nna-m’ or ‘nna-nna’, which actually means father but in this context is given to a child. They’d also say ‘bịa’: come here. And if you heard ‘wahala’ you were in trouble. ‘Wahala’ means stress, so one of your parents saying ‘you give me “wahala”’ was the last thing you needed.

My dad still uses some of it now as a little reminder, but I’m convinced that back then he’d speak in Igbo to others to make sure we didn’t understand what he was saying. We might be at an aunt’s house or someone was visiting us, and they’d either 18spend the whole time speaking in Igbo or a conversation that had started in English changed language part-way through, and we wouldn’t have a clue. It would have been partly subconscious but partly deliberate, knowing my dad. He enjoyed throwing a spanner in the works. I don’t mind that he did, either, because it’s helped me retain a good sense of what the culture entails.

Those first few years in Manchester were difficult for both my parents. My dad joined us in 1992 and immediately went to study at the University of York before going on to spend two years at Manchester Metropolitan University training to be a teacher. His first proper job in the UK was teaching maths in a high school. My mum, who was now Dr Anthonia Onuoha, found that as a black woman in early 1990s England, getting a PhD had made things worse for her, not better. My mum had worked incredibly hard to get her doctorate, but now she was consistently told she was overqualified for jobs, and she suffered because of it. Looking back now, I seriously doubt that her main problem was being overqualified. It seems far more likely to me that prospective employers in early 1990s England were intimidated by the name that appeared on the application. To get a job she would have to overcome the stigma of being firstly a woman, then a foreigner. That’s before you consider that ‘Anthonia Onuoha’ was preceded by ‘Dr’. Even in 2020, some people in America were refusing to call the wife of then President-elect Biden ‘Dr’ Jill Biden. There was an infamous op-ed in the Wall Street Times claiming that because her doctorate wasn’t anything to do with medicine, she shouldn’t use the title. How many times has that standard been applied to men? You could be a doctor of something ridiculous like television screens, and because you’re a male that’s fine. My mum spent a large part of the first few 19years we lived in Manchester doing work like putting leaflets inside newspapers, because that was the only job people were willing to give a black woman who had a PhD in environmental sciences from Salford University.

• • •

This is how it began in the UK for Anthonia and Martin Onuoha (my father had decided to use his middle name after moving) and their three children. We were in east Manchester, a lot of which has been gentrified in the time since I lived there – just five minutes down the road there’s a place called Ancoats, which looks swell now – but the same investment hasn’t yet made its way to Miles Platting. It’s exactly like it was all that time ago: poverty-stricken and affected by low-level crime. It wasn’t a case of gangs being everywhere, but young people in particular would do illegal things just for a laugh. Every time my parents bought a new car – one that was new to them, not brand new – it would be burnt out or have its tyres and other parts removed. I remember one year around Bonfire Night, these guys were letting off rockets from the exhaust pipe of my dad’s tan Nissan Sunny. It was just a group of lads who thought it was funny, but I’ll never forget how my dad dealt with them, heading out of our front door to grip one of them by their collar, lifting him off the ground. Fight, not flight. They were in their late teens or early twenties, but the one my dad had in his grasp just started crying his eyes out as his friends skedaddled. This was the calibre of criminal: the kind who would run away, say if nine- and six-year-olds walked in on them trying to steal something from a house. I can understand why someone might have met their match with my dad, though. 20He’s just a bit smaller than me now, but he’s a strong fella. He showed them aggression, and they wanted none of it. I watched it all while looking out of the window and thinking, yeah, good luck guys, good luck with that one. I always felt protected by my father, and he made sure we never felt vulnerable in what could at times be a threatening environment. And it wasn’t just him: if it was a verbal confrontation, my mum would be the one mixing it with whoever dared to take her on!

Like my parents, I don’t really take to being bullied, and like those guys firing rockets out of our car exhaust, there was someone who found that out the hard way. At school, as a five-year-old battling the cold of a new country by wearing what I can only describe as a ton of coats, I was a target. I was a black foreigner with an accent in a very white space, and even though I was a child some of the other pupils weren’t familiar with diversity, certainly not in the way they might be now. You know what kids are like with someone who’s different: they try to alienate them, and they’ll joke around at the expense of the new, strange-looking boy, saying, ‘Look at this guy,’ and ‘What’s this?’ One of them had said something to upset me, and when I went home and told my parents they said I should stand up for myself. The next day, when that same kid tried to poke fun at me again, I very much stood up for myself. I headbutted him. It’s the most instinctive thing I’ve done in my life, and it’s certainly the only headbutt I’ve ever delivered. The boy didn’t bleed, but he did cry. I started to worry about being in trouble, which I was, but only at school, not at home. My parents understood all too well what would have led to that moment.

I think I had some sense of regret at the time, but ultimately people did treat me a bit differently afterwards. It was the first 21step on a long journey to discover the strength to speak up in the face of bullying, which is something I encourage my children to do now. Even though I was always one of the bigger kids for my age, I wouldn’t necessarily have had the biggest presence because I’ve not always been somebody who is good with words or particularly outspoken. My eldest daughter, Amaia, is the sweetest girl in the world, and my biggest concern is that someone is going to be mean to her. She doesn’t deserve that, but if it happens, I’m always going to try to get her to stand up for herself. Not through violence but through understanding her own value and speaking to the right people so that it can stop. I’ll tell her to call the bullying out for what it is and never to let anybody push her down, because it’s wrong. I’ve since come to appreciate the lessons I learned in those early days at Miles Platting Junior. When you’re in the moment, you just take it day to day and you don’t think too much about it. I didn’t know how to react when I was being bullied, and I certainly didn’t imagine I’d be headbutting anyone, but I can now look back and try to teach my children the same lessons I have come to learn about how important it is to speak up and seek help.

• • •

Our immediate experience of British culture was limited in Manchester, because most of the people my parents spent time with were originally from either Nigeria or other parts of Africa. You could have been anywhere in the world when you stepped into those houses, because once inside they all felt the same. My first window into what you might call traditional British life was provided by the Wyon family. Andrew Wyon had had 22a contract with Delta Steel in Nigeria and met my dad during the time he spent working in Warri. On Andrew’s last day there, he invited my family to visit the Wyons at their home in Bath. That summer, and for many summers afterwards, we spent part of the holidays with Andrew and Linda Wyon at a house that felt like a whole other world to us. It was massive, old, very British (imagine late-’80s décor!) and bordered by a golf course. We didn’t have a back garden in Miles Platting, so we would spend the days whizzing down the big water slide they had in theirs. There was so much space just to go wild. Then, we’d eat rhubarb crumble. Rhubarb! Just incredible. They’d grow it in the garden and make all sorts of puddings with it. This, I can guarantee you, was the first time I’d had rhubarb. It was also the first time outside my own house that I could be myself. I have a memory of one Christmas visit when I was doing a stupid dance, being silly and playing the joker, happy to try to entertain the adults with everyone laughing at me. It was so different from home. I always enjoyed spending time with the Wyons, who got on well with my parents, and as they had fostered kids from all kinds of backgrounds during their lives, the first time we visited them Diuto, Chidi and I became like three more for them to care for. My dad describes the Wyons as our first British ‘family’, and we’d call Linda and Andrew ‘auntie’ and ‘uncle’. They were wonderful human beings and so welcoming. Although there was one thing I didn’t like: their cat. It used to scare the life out of me, and I’ve got the heebie-jeebies just thinking about it. That’s probably where my dislike of animals comes from. That and Buster.

Back home, the joys in my life came from football, and for a while netball too. Diuto and I would play together, and the netball coach at Miles Platting Junior encouraged me, despite 23it being taboo for boys to play the sport. The coach was called Maria Kennedy, and she is my favourite teacher of all time. We’re still friends now. She was effervescent and made me really want to play netball, even though I was the only boy doing it. Her support was pivotal in me not being bullied, and so I was able to go to practice and have great fun doing it. Why wouldn’t I? I was running and catching a ball. What more could I ask for? Well, maybe kicking it…

I used to play on the streets around my house during the summers in Miles Platting, but my first real football memories come from a park five minutes away, just off Alan Turing Way – not the one where Buster would chase me, but very close to it. We’d put jumpers down for goalposts and just play and play and play, for hours at a time. I loved it, partly because I considered myself lucky to be able to do it (I had to ask permission from two parents who didn’t encourage me to have any social life for the rest of the year when I had schoolwork to concentrate on) and partly because I quickly realised I was good at it. Whether it was in a game of Wembley (pairing up with someone in a knock-out tournament) or five against five, I was one of the best players. Sometimes that was a problem. One of my neighbours would provide the ball for our games, and he once told me I was so good there was no point in him playing any more. He took his ball and went home. I didn’t have a ball of my own, so that was the end of that.

Those who are familiar with this part of east Manchester will realise I’ve not yet mentioned a very significant landmark that has appeared in the years since I left: the Etihad Stadium. I’ve often had the chance to reflect on how fitting it is that my earliest football memories are from a field that is now in the shadow 24of Manchester City’s ground. Every time I drove there as a City player, I passed the house where I first lived in the UK, thinking, ‘I went from there to there,’ from 391 Bradford Road to the Etihad. Even to this day, when I go to the stadium to work for the media, I pass the house and think of the memories it brings. It was an important part of my history and where my football journey started, but I’m so glad I don’t live there any more. More than two decades on from when my family survived there just by making do, thousands of City fans walking to and from the stadium each matchday pass that house, completely unaware (until now, perhaps) that one of the players they cheered for – and who cheers for their team still – fought there to fit in to a new country and establish an identity that would end up being defined most by the blue of Manchester City.

Eventually, I started playing organised football, first for my school and then for a team called AFC Clayton. I was a year young for the Miles Platting Junior team, but I was still able to do well enough for the coach to say I should try out for a Sunday League side. I didn’t even know what Sunday League was at this point, so he gave me a piece of paper with a whole load of teams, training schedules and phone numbers, and as AFC Clayton were only a few minutes up Ashton Old Road from where we lived, I chose them. I went for a training session, and just like that I was playing for the team. Well, teams. In my first season, which was 1996/97, I played for both my age group and the one above, one on Saturdays and the other on Sundays. By the end of that season, I’d won player of the year in both the Under-10s and the Under-11s, the trophy for most man-of-the-match awards (in both teams), and I was the Under-10s top goal-scorer too. I know all this because I still have most of the trophies on display in my 25house! That’s not to say both teams were successful, though. At that same end-of-season awards ceremony, the Under-11s celebrated their biggest win (7–6) and biggest away win (4–3), which were both against the same team, Ashton Moss. They were the only two victories we had the whole year, and we got absolutely battered in every other game.

One of my man-of-the-match awards came in the Divisional Cup final, which we won and celebrated by going on an open-top bus ride. I was buzzing! But that wasn’t the only momentous thing to happen that day. I’ll never forget the feeling when my dad came to me after the game and told me that someone from Manchester City had scouted me and wanted me to go for a trial. This was half the story: I found out much later that a Manchester United scout was also there and my dad had turned him down on my behalf. He claims he did it because I was a City fan and he figured out I’d probably not want to play for United, but at the time I didn’t really support City. I liked them, which considering United was the