Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

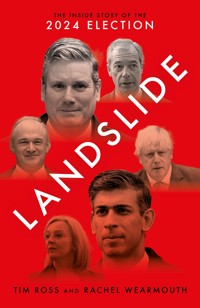

On 22 May 2024, Rishi Sunak stood outside 10 Downing Street and announced an early election, in an attempt to catch his opponents by surprise. Just minutes later, Tory hearts sank, with images of the Prime Minister soaking in the rain instantly defining his hapless campaign. The next six weeks delivered more mistakes, a betting scandal, apocalyptic Tory polls, bitter backroom arguments and finally the worst result in the Conservative Party's 190-year history. Keir Starmer's Labour, meanwhile, stormed to victory with one of the biggest landslides on record after fourteen years in the wilderness. But the party won with its fewest votes in almost a decade, raising questions about how popular Starmer really was. Scotland's voters abandoned the SNP, Ed Davey's Lib Dems surged to their best election ever and Nigel Farage once again blew up the Conservative Party's plans. This gripping account by seasoned Westminster journalists Tim Ross and Rachel Wearmouth tells the full inside story of the key tactics and powerful forces that delivered the most seismic upheaval in a generation. What role did Starmer's character play in his party's success? How did Labour's election machine engineer such a devastatingly efficient vote? Was there anything Sunak could have done to avert disaster? What does it all mean for the future of Britain? Blending exclusive interviews and explosive accounts from key players, Landslide sets out to answer these questions and more, revealing a dramatic and sometimes disturbing picture of British politics at a turbulent time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

praise for betting the house:the inside story of the 2017 election

“It’s the political book of the year: a gripping inside account of what really went on behind closed doors as the Tories bungled to election disaster and just how close the fiasco came to toppling Theresa.”

Mail on Sunday

“Read it in one sitting. Absolutely gripping stuff, a terrific story well told. This is likely to be the definitive account of a most unusual election, one of the great surprises of British political history.”

John Rentoul, chief political commentator for The Independent

“The thrilling account of the most dramatic election in recent history.”

Robert Peston, ITV political editor

“Excellent.”

The Economist

“Compelling … A well-constructed narrative which gives a lively account of the campaign while also reflecting astutely on the underlying forces that shaped the result.”

Andrew Rawnsley, The Observer

ii

iii

praise for why the tories won: the inside story of the 2015 election

“This book is brilliantly clear about how it was done and who did it.”

John Rentoul, The Independent

“Probably the most revealing of all the election books so far.”

The Guardian

“Any activist wanting to better understand, or, dare I say, win elections, should read this book.”

Progress

iv

v

Contents

Introduction

At 10 p.m. on Thursday 4 July 2024, the transformation of British politics began.

The broadcasters’ general election exit poll put Keir Starmer’s Labour Party on course to take power, with an enormous landslide of 410 seats. That was more than double the total the party won five years earlier. Starmer’s power would be unassailable, at the head of a huge House of Commons majority.

The seat forecast was a complete humiliation for Rishi Sunak’s Conservatives. They were very nearly destroyed as a political force. After fourteen years in power and five Prime Ministers, the Tories were set for just 131 seats – the lowest ever tally in the party’s 190-year history, the exit poll said. When the results came in, it was even worse.

On sofas at home with loved ones, and in campaign offices surrounded by aides, the protagonists in the drama of the 2024 general election were transfixed. The thing about a seismic upheaval is that it can take those involved a while to process. As Starmer hugged his family tight, watching the pundits discussing his imminent appointment as Prime Minister, his most loyal aides just stared at the xscreen in silence. One remembers thinking, ‘I don’t know how I’m meant to feel now.’1

Sunak’s team, scattered hundreds of miles apart, also had mixed emotions. The Conservatives had been ruined but not quite eradicated. It was awful, and there was grief, but it could have been worse, they thought. At least the Tories would still get to be the official opposition.

Ed Davey’s Liberal Democrats, finally out of the electoral dog-house, could not quite believe they were projected to grow from a band of eleven to sixty-one MPs. They hugged and screamed at each other with delight. The final result was even sweeter.

The shell shock, giddiness and confusion continued in the days that followed. Several senior Labour MPs didn’t bother answering their phones when a ‘withheld number’ called on the morning after the election. It was No. 10 summoning them to meet the new Prime Minister so he could appoint them to the Cabinet.

Rachel Reeves was stuck in traffic and running late, which made her already frayed nerves even worse. She was trying to prepare herself for the long walk up Downing Street in front of the world’s media to be appointed Britain’s first female Chancellor. But her driver was playing some intense R&B music on the car radio. It was a bit much for Reeves, who asked for something calmer.

‘Smooth Radio?’ the driver offered. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Smooth Radio.’2

• • •

This book is an attempt to understand the forces that dramatically recast British politics in 2024.

Labour won its first election in nineteen years, with 411 seats. The Tories fell to just 121 MPs, while the Liberal Democrats leapt xito seventy-two. In Scotland, the SNP collapsed, losing thirty-nine seats. Nigel Farage powered back into the political front line and into Parliament for the first time. His late entry into the contest as leader of Reform UK blew up the Tory campaign and cost Rishi Sunak’s party dozens of MPs. Even though Farage’s team only secured five seats, they won more than 4 million votes and have changed the dynamic in ways that may not be clear for some time.

Why was it that nothing the Conservatives tried ever seemed to work? How could the country’s most successful political party finally lose its winning touch so spectacularly? Was there anything Sunak could have done? What did Labour do this time that was different to the previous four elections that the party lost? What kind of a leader is Keir Starmer and how did his character shape the end result?

Morgan McSweeney, Labour’s campaign director – who was later promoted to be Starmer’s chief of staff in No. 10 – ran a highly disciplined operation. His team delivered the most efficient vote-to-seat ratio in history. How did McSweeney do it? What role did tactical voting play? What do the results say about the state of British politics and how will they shape what comes next?

Did the public even care? At 59.7 per cent, turnout was lower than at any election since 2001. It was generally lower in seats won by Labour than in seats won by the Tories.3 The pollsters – and the obsessive way the media reported every one of their surveys and seat projections – may partly be to blame. Before a single ballot had been cast, most voters felt certain that a big Labour win was inevitable. How did that affect the outcome?

In order to answer some of these questions, and others, this book draws on more than 100 interviews, private conversations, official documents, text messages, emails, Zoom calls, strategic memos, xiipresentations and other information from people involved at all levels of the national campaigns in Westminster and in Whitehall. The vast majority of those who provided information and detailed first-hand accounts wished to remain anonymous to give their candid views on what worked and what did not. Many now work at the highest levels inside the new government and are not authorised to speak publicly. Others used to sit at the same desks and are now licking their wounds and trying to rebuild their careers outside politics.

Politicians and their aides watch their words carefully in public, but when speaking in private, as many have done for this book, some tend to pepper their language with profanities. We have chosen to retain their original language in direct quotations in the interests of authenticity. There were also moments in the campaign when racist language was aired that some readers may find upsetting.

• • •

The focus of this book is on the battle for power, and that was always only a contest between Starmer and Sunak. It was a contest fought mainly in England, although Labour’s resurgence in Scotland swelled Starmer’s majority.

The first part of the book deals with the build-up to the election, tracing the impact of the toxic legacies that both party leaders inherited on their preparations for the campaign. That political baggage – and how Starmer and Sunak dealt with it – had a huge influence on the results in 2024. The second part explains the Labour and Tory election plans and how the campaign directors prepared their activists for the so-called ‘ground war’. In the short campaign, rival parties compete to define the contest at national level in the media xiiithrough policy pledges, speeches, manifestos and TV debates. The digital campaign, fought via social media channels on smartphones and websites, is now a central part of every election.

The third part deals with the campaign events that unfolded in the six weeks before polling day, including Sunak’s D-Day debacle, the election betting scandal and the remarkably effective performances of Ed Davey’s Liberal Democrats and Nigel Farage’s Reform UK. It also takes a hard look at the polling industry in 2024. The fourth tells the dramatic story of the night of unprecedented upheaval that followed the exit poll on 4 July. The final chapters reflect on what the outcome means.

• • •

Elections are the moments when millions of citizens living in democracies exercise their muscle. Frontline politicians are the ones who get crunched or, if they’re lucky, crowned winners. The story that unfolds in these pages sometimes reveals a picture of professional politics that is not flattering. The UK has suffered repeated bouts of turmoil over the past decade, with senior figures in both main Westminster parties guilty of failures of leadership, backroom plotting and feuds that have little to do with voters’ priorities.

Despite that history, most people working in British politics do not primarily seek fame or personal advancement. They want to contribute to making the country a better place to live and work, often holding strong convictions over how best to achieve this. Elections are the moments when they get their chance. It is a high-risk business, and the rewards are rare and temporary. Most people lose, most of the time.

The two leaders vying for power in 2024 were unusual. They were xivclassic mainstream centrist politicians of the type the UK has not had a chance to choose between for almost a decade. The transfer of power between Sunak and Starmer was smooth, courteous and good-natured. But a radical anti-politics mood is not far away, as the riots that swept the UK after the Southport stabbings in the summer of 2024 showed.

At the time of writing, the Conservatives are choosing a new leader. It will be either Robert Jenrick or Kemi Badenoch, both of whom hail from the right wing of the party, economically and socially. Nigel Farage’s already powerful influence is likely to weigh heavily on whatever His Majesty’s new-look opposition does in the years ahead.

Labour’s landslide buried the Tories in 2024. But the ground is still unstable. If Starmer’s opponents find a new figurehead who can connect with the public, as Boris Johnson did only five years earlier, another seismic change could soon follow.

353Notes

1 Interview, Labour source

2 Private information

3 Georgina Sturge, ‘2024 general election: Turnout’, House of Commons Library, 5 September 2024, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/general-election-2024-turnout/

PART I

THE LEGACIES2

Chapter 1

King Boris

SHUFFLING

It was meant to be routine.

Boris Johnson, the Conservative Party’s blond, bomb-proof, election-winning machine, had decided two months into his first full term in office to reshuffle his Cabinet. The truth was that Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s subversive chief adviser, was the one doing most of the hiring and firing, and that was always liable to be explosive.

It was 13 February 2020 and Johnson was all-powerful. He had just led the Tories to their biggest election victory since Margaret Thatcher’s landslide in 1987. Cummings, whose menacing utterances gripped most government colleagues with fear, was also at the height of his maverick influence. Bald, thin and prone to volatile outbursts, his shadow loomed over Westminster. He had a plan to remake the centre of government to consolidate Johnson’s (or rather his own) authority, while ripping up what he derisively called the ‘blob’ of established Whitehall orthodoxy in order to reform the entire country. Central to that mission, and not for the last time in 4this story, was an attempt to tame the most powerful government department, the Treasury.

It is an unwritten rule of British politics that tensions are intrinsic to relations between the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. A dynamic of conflict is almost built into the structure of the two roles: the PM is the figurehead, the leader with (usually) a popular mandate direct from voters to deliver on election promises and spend taxpayers’ money on the country’s priorities. The Chancellor, however, is the bank manager who is constantly being asked to stump up the cash. More often than is comfortable, it falls to the top minister at the Treasury to say ‘No.’

In the case of Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, Labour’s longest-serving double act, relations between the two were disastrously toxic. Wary of the risks, David Cameron and George Osborne consciously worked to maintain their exceptionally close partnership during the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition of 2010–15, even redesigning the interior layout of 10 and 11 Downing Street – where the PM and Chancellor had their respective offices – to ensure a free flow of staff, ideas and goodwill.

When Chancellor Sajid Javid wandered up the most famous street in London for Johnson’s reshuffle, he was expecting to be confirmed in his role in a matter of a few seconds and to leave again to resume preparations for his first Budget.

Instead, he was ambushed. Johnson congratulated Javid on his reappointment but issued a condition. The Chancellor must fire his six top Treasury advisers – effectively neutering his ability to choose his own team – and allow Cummings to appoint their replacements, who would all report to No. 10.

A stunned Javid could not believe what he was hearing. When it became clear that Johnson was not, for once, joking, he quit. ‘They 5wanted his balls in a jar,’ one ally recalled later. ‘He is rather attached to his balls.’1

Javid himself later described Cummings’s sway over Johnson’s government as far too powerful. Often, Johnson would have no knowledge of decisions being taken by Cummings in his name, which Javid objected to, saying later, ‘At best, it was like having two Prime Ministers and sometimes they agreed and sometimes they didn’t. At worst, you had one Prime Minister, it just wasn’t the elected one.2

Javid’s dramatic departure opened the door to No. 11 for one of his friends – the diminutive, self-effacing, always-smiling young MP for Richmond in Yorkshire. At thirty-nine, Rishi Sunak became Johnson’s Chancellor, one of the youngest holders of the second-biggest job in government.

Javid and Sunak were friends. They shared a background in investment banking (which made them both a lot of money) and a love of StarWarsfilms. A week after winning the 2019 election, Sunak, who was Chief Secretary to the Treasury at the time, tweeted a picture of himself with Javid at the cinema where they had just watched TheRiseofSkywalker. ‘Great night out with the boss – Jedi Master @sajidjavid,’ he said. Javid responded with his own tweet that, looking back, reads more like a warning to Johnson about what was to come: ‘The Force is strong in young Sunak.’

It was a rapid rise for the Cabinet’s apprentice. Barely seven months earlier, Sunak had been a junior minister in the local government department. Newly installed at the Treasury, he had to contend with the small matter of a Budget due in three weeks.

Sunak’s appointment as Chancellor came a fortnight after the UK had formally left the European Union, and most of Westminster believed his biggest task would be getting the country ready for life outside the single market and customs union. Under the terms 6of Johnson’s bare-bones EU exit deal, the British had been given a ‘transition period’ lasting until the end of 2020 in which to prepare for the economic shock of severing ties with their closest and biggest trading partners. In the meantime, existing EU rules would continue to apply to the UK until that grace period expired.

Johnson had won his eighty-seat majority in December 2019 on a simple promise: after three years of chaos, with a paralysed Parliament refusing to endorse Theresa May’s EU withdrawal plan, and with Labour proposing to rerun the referendum campaign, voters should give him a decisive mandate to ‘get Brexit done’. The electorate agreed and the UK duly left the EU at 11 p.m. on 31 January 2020. Amid celebrations inside No. 10, Johnson made a characteristically idiosyncratic speech to his aides and supporters, celebrating the fact that ‘French knickers’ would now be ‘made in this country’. Dominic Cummings, who had masterminded the 2016 Vote Leave campaign, also had the chance to speak. But the occasion was too much for him: overcome by the scale of the Brexiteers’ achievement, he wept.

Sunak was an enthusiastic Brexit supporter and an early backer of Johnson’s leadership campaign after May resigned the previous summer. He had good reason to be looking forward to a long partnership with the new PM, making Brexit a success and fulfilling the Tories’ 2019 election pledge to ‘unleash Britain’s potential’.

Indeed, in the first weeks of 2020, Johnson was in the rare position of having brought together a Conservative Party that had spent the previous four years ripping itself to pieces over Europe – a civil war that had already claimed the scalps of his two predecessors as Prime Minister, along with multiple other senior Tory figures and former members of the Cabinet.

The official mission of Johnson’s new administration was to ‘level up’ the UK, bringing a boost to regional economies in parts of the 7country that had been neglected for investment and had fallen into decline. Many of these were fervently Brexit-supporting areas, such as in the Midlands and the north-east, districts which had formed part of Labour’s so-called ‘red wall’ heartlands but had voted decisively for Johnson in 2019.

In one Conservative Party broadcast in February 2020, Johnson personally thanked a voter referred to only as David from Bolton, who worked in highway maintenance. Over some acoustic guitar music, the caption told viewers that David, who previously backed Labour, had voted Tory for the first time in 2019. ‘We wanted to thank him for placing his trust in us,’ it said.

After a brief shot of Johnson being prepared backstage, David described how his parents were both Labour voters and he’d always believed Labour were ‘the party for the working man’ but was excited now because voters had ‘given Boris a chance and I want to see how he takes that chance and runs with it’.

Then came the theatrical moment of surprise, in which Johnson walked on set and shook his shocked and grinning voter by the hand. But David recovered his poise to give the Prime Minister what amounted to a serious warning: ‘The thing that I liked that you said, I think it was your first speech after winning the election, you said you’re almost treating it as like you’d rented our vote, you’re not going to take that for granted. That was important for me to hear.’

Johnson replied that this was his message to Tory MPs, too. ‘We have to repay the trust of the electorate,’ he said.

SHAKING HANDS

Those who have worked closely with Johnson describe a leader who has a rare ability to communicate and connect with the public. He 8inspires loyalty bordering on adoration among a few people who get close to him. In No. 10 he was addicted to a level of organisational chaos that made administering the affairs of the state a task far beyond his own abilities. That significantly complicated matters for those whose job it was to try to make things work. Boring meetings bored him and he was liable to change his views frequently.

Around the same time the video of David from Bolton was released, reports began to filter through to Whitehall of an outbreak of an unknown, flu-like illness in China’s Wuhan province. Government officials decided to do what they do best and convene some meetings, including meetings of the Whitehall emergency committee known as COBRA. These gatherings are often technical affairs, bringing together senior figures in the UK’s scientific and medical establishment with communications officers and ministers. Johnson, though he could have attended, decided to skip them.

Like many of the stickiest situations Johnson has found himself in over the years, the Covid crisis did not evaporate when he ignored it. By early March 2020, it was consuming virtually all the government’s attention. Thanks to the prevalence of cheap air travel, the virus had spread fast and far beyond China. It was overwhelming the healthcare system in northern Italy, where hospitals were running out of beds, ventilators and intensive care space at frightening speed. One after another, governments in the west took the unthinkable decision to order their citizens to stay at home in an attempt to slow the dispersal of the disease. A new word entered public consciousness: lockdown.

Johnson came to power as a popular libertarian who rarely allowed himself to be constrained by convention and delighted in behaving as if the usual rules of politics and public life did not apply to him. Rule-breaking worked well for his brand and voters responded 9warmly to a candidate they saw as engagingly different from the slickly produced cut-out of a typical politician. He initially regarded the coronavirus scare as something to make light of, boasting to reporters of having visited a hospital where he ‘shook hands with everybody, you’ll be pleased to know,’ when asked if members of the public should stop using handshakes as greetings.

Cummings, by his own incendiary and colourful account, was horrified at his boss’s attitude. Then, on Saturday 14 March, a crucial meeting took place in Downing Street at which Johnson was for the first time receptive to the idea of imposing severe restrictions on the public to help slow the spread of disease. Cummings was particularly vocal in his support for restrictions. Yet it took nine more days for the Prime Minister to act.

On 23 March, Johnson finally ordered the first national lockdown, asking the public to stay at home in order to protect the NHS and save lives. ‘You should not be meeting friends,’ he said. ‘You should not be meeting family members who do not live in your home. You should not be going shopping except for essentials like food and medicine – and you should do this as little as you can.’ Anyone who disobeyed these instructions would find themselves in trouble with the law. ‘If you don’t follow the rules, the police will have the powers to enforce them, including through fines and dispersing gatherings.’

LOCKDOWN

The first Covid lockdown of 2020 wrought an unimaginable change on the nation.

For those not working in the NHS, daily life stopped. The warm, sun-filled days in March and April unfolded in an eerie stillness, filled with an absence of noise. Shops and offices stood shuttered, 10roads lay empty of traffic, even the sky, unendingly blue, was free of planes. In place of the usual clamour of city life came the sound of birdsong and the breeze, animating spring leaves and scraps of litter on empty streets.

For the Tory government, and its new Thatcherite Chancellor in particular, the change in economic outlook that the pandemic required was no less disorienting. The novice at the helm of the Treasury found himself designing a programme of what he would later proudly boast of as £400 billion worth of government spending on Covid-19 support measures. Chief among them was the vast furlough scheme, under which the state paid the bulk of the wages of people whose workplaces had been ordered to close.

‘Today I can announce that, for the first time in our history, the government is going to step in and help to pay people’s wages,’ Sunak said on 20 March. In a mark of how quickly the pandemic was taking over, Sunak made this historic intervention only three days after he had delivered a full Budget. He returned to Parliament multiple times to announce extensions of the furlough and business-loan schemes and came forwards with other forms of support, including ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ subsidies to encourage people to go to restaurants and cafes for meals, in order to help revive the hammered food and drink industry.

For the low-tax, small-state advocate Sunak, along with many of his Tory colleagues, it was a jarringly uncomfortable position to be in. One Cabinet minister, stunned by the scale of public spending, privately joked that the reason voters rejected the unreconstructed socialist Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in 2019 was because ‘he wasn’t left-wing enough’ for them.

During the pandemic, Sunak was hugely popular with the public, thanks to the fact that, in the words of one aide, ‘he nationalised 11payroll’. By the summer of 2020, his ratings were the highest of all politicians who were scored for their handling of the pandemic: according to Ipsos, 60 per cent of the public thought the Chancellor was handling Covid well, compared to 43 per cent for Boris Johnson and 31 per cent for the newly elected Labour leader, Keir Starmer. Only Chris Whitty, England’s chief medical officer, who was revered and relied upon as the nation’s doctor during daily televised press conferences, scored slightly higher than Sunak, with 62 per cent approval.

But not everyone was happy with the government’s willingness to shut down economic activity. Soon, cracks began to emerge in the Conservative Party’s consensus, with vocal libertarian MPs such as Steve Baker and others objecting to the freedom-limiting Covid restrictions and the impact they were having on the economy. Over the next year or so – as curbs were imposed, lifted and then reintroduced – the dissent spread to the Cabinet. Sunak was on the side of easing the rules, while others were persuaded by the need to lock down hard, as expressed by Chris Whitty.

‘People like Rishi, [and Cabinet members] Alok Sharma and Jacob Rees-Mogg were pushing back on Covid restrictions,’ said one senior government figure. They argued that ministers should ‘give people information and let them take their own choice. The government shouldn’t be locking down, it shouldn’t be restricting freedom. It shouldn’t be killing off the economy.’3

But the reality of the medical emergency gripping the country was horrifying – as was the government’s apparently poor record at dealing with it. In November 2020, the UK passed the landmark of 50,000 Covid deaths (a figure which would eventually rise well above 200,000). Only the US, Brazil, Mexico and India had passed 50,000 deaths by the same point – all countries with far larger populations than the UK.

12As a classic libertarian himself, Johnson wrestled with the arguments for and against lockdown, changing his mind frequently on policy and earning from the acerbic Cummings (and apparently others) the contemptuous nickname of ‘Trolley’, a reference to the fact that he would change direction unpredictably, like a shopping trolley with a wonky wheel.

In one sense, the turmoil within the PM’s own mind embodied the party’s wider divisions over the right way to run the country in general. One striking thing about the way the Tories went to war with themselves over Covid was how closely the factions mirrored the groups that fought each other on Brexit. ‘The issues that blew the party apart over Covid were exactly the same,’ a senior official recalled. ‘The ERG [the hardline Eurosceptic European Research Group of Tory MPs] just turned into the Covid Recovery Group.’4

For Steve Baker, who was a driving force behind the Brexit campaign in Parliament and within the Covid Recovery Group, lockdowns offended the animating philosophy of his politics: ‘If the Conservative Party does not stand for freedom, it stands for nothing.’5

KING BORIS

Only a few months after Johnson won his eighty-seat majority, his authority suddenly seemed to be on shaky ground. Rebellion was in fashion. Splits, negative briefings and backbiting were rife. ‘They had about six months when King Boris was able to unite the warring tribes,’ the same senior official said. ‘But the pandemic comes along and just creates another lightning rod for these quite fundamentally different views in the Conservative Party of how you’re supposed to govern this country.’6

13Some who were working closely with Johnson’s top team at the time blame the cruel timing of the pandemic lockdown for robbing new MPs of the chance to feel part of a bigger party in Parliament. If the 2019 intake of Tory MPs had been able to rub along together in the bars of Westminster, the Tories in the Commons might have gelled into more of a team. ‘I don’t think that sense of unity ever existed,’ one former Cabinet aide recalls. ‘The 2019 intake arrived and all of a sudden the pandemic hit and they all dispersed around the country. It was never really a single party – they were all on their separate WhatsApp groups winding each other up.’7

Even while tens of thousands were dying in care homes and hospitals, Johnson displayed at best an ambivalent attitude toward Covid restrictions. On 27 March 2020, it was announced that he had caught the disease himself. Colleagues in No. 10 at the time privately blamed Johnson’s reluctance to follow doctors’ advice – he had carried on working, refusing to give an inch to the virus, and became progressively more unwell, they said.

Ten days later, Johnson was in hospital in intensive care, from where news filtered out to a shocked country that the PM was on oxygen to help him breathe. Inside No. 10, some officials began to panic, genuinely believing he would die. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, grey-faced and worried, was asked to step in and deputise.

Johnson survived and credited the NHS with saving his life. Clearly weak and still short of breath, he gradually returned to work, praising the healthcare he had received and renewing his calls for the public to obey lockdown and follow social distancing rules when taking exercise outside once a day or buying food or medical supplies.

On 13 April 2020, a day after Johnson left hospital, YouGov polling gave him the highest rating of his entire premiership, with 66 14per cent of adults saying they believed he was doing ‘well’ as PM. This frightening virus had made the public want to believe in their leaders, to put their trust in the figures of authority responsible for keeping them safe and follow the rules.

Six weeks later, that faith was shattered.

On 22 May, the DailyMirrorand TheGuardianreported that Cummings had been investigated by police for allegedly breaking lockdown after he was seen at his parents’ home in Durham, some 260 miles from his normal place of residence in London. He was also spotted on his wife’s birthday at Barnard Castle, a beauty spot.

At the time, during the UK’s first national lockdown, the government was telling the public to stay at home and all non-essential travel was banned. On the face of it, this was an appalling betrayal, the most grotesque hypocrisy by a powerful official who seemed not to believe that the usual rules applied to him.

Two days after the first reports, Cummings held a press conference in the Downing Street garden to explain himself to the country. He feared he and his wife were becoming ill, he said, and worried how their four-year-old son would be cared for, so went in search of a childcare back-up plan to stay at his parents’ property. Cummings was ridiculed after he tried to explain the trip to Barnard Castle as necessary to test his eyesight. BrewDog produced a new IPA beer called ‘Barnard Castle Eye Test’ to mark the scandal, while one well-known high street optician recorded a 6,000 per cent increase in online mentions of their advertising slogan: ‘Should have gone to Specsavers.’ The firm also placed a free eye-test voucher on the back of parking tickets in the County Durham town.

Johnson himself defended Cummings, saying he ‘at all times behaved responsibly and legally’ and had followed the instincts of every parent. But the relationship between the Prime Minister and 15his aide did not recover after the Barnard Castle incident, according to Downing Street colleagues. Later in the summer of 2020, Cummings urged Johnson privately to carry out a radical Cabinet reshuffle to focus minds amid headlines suggesting the government had no grip on the Covid crisis. Johnson, he said, looked like he was happy to have a Cabinet of ‘useless fuckpigs’ in charge, identifying Gavin Williamson, the Education Secretary, and Matt Hancock, the Health Secretary, as among the least capable ministers who were letting the country down. Johnson rejected Cummings’s plan. It was a sign that the two were no longer on the same page.

One senior Tory still cannot believe how much political capital Johnson blew on defending his adviser:

When you win a big mandate like Boris did, with 43 per cent of the vote, you feel it on the ground. Everyone who wins that big a vote share gets one ‘mea culpa’ moment. He used his defending Dominic Cummings’s hypocrisy. He burnt all his capital on Cummings. It was absurd.8

Johnson himself recovered from his illness, but it took time. During his repeated defences of Cummings, he would occasionally be hit by a bout of coughing. On his birthday in June, his wife Carrie – herself a former Tory Party adviser and a powerful influence on his decisions – organised a celebration in the office with a cake. Up to thirty guests sang him happy birthday. There was just one flaw in the plan: such gatherings were prohibited under Johnson’s own Covid rules at the time.

Conor Burns, a longstanding ally of the Prime Minister, tried to explain that the event was not a ‘premeditated’ party, though his choice of analogy didn’t help. ‘He was, in a sense, ambushed with a 16cake,’ Burns suggested. The idea of the British Prime Minister falling victim to a stealth attack by an aggressive teatime treat piled ridicule on top of the government’s attempts to explain Johnson’s actions, further undermining his credibility.

Although the gathering was reported soon after it happened, the story was merely tucked away in an article in TheTimesand no mention of lockdown-breaching scandal was made. It wasn’t until two years later that the country came to understand the full scale of rule-breaking behaviour that went on inside Johnson’s Downing Street. The so-called Partygate news reporting – led by the DailyMirror’s political editor Pippa Crerar and added to by others across the media, including ITV’s Paul Brand – revealed a sordid portrait of debauchery in Downing Street.

One celebration in April 2021, in which two leaving parties – for one of Johnson’s photographers and for James Slack, who had been the PM’s communications director – joined up later in the night in the No. 10 garden was particularly wild. According to one witness, a staff member was sent out to a local shop to return with a suitcase full of wine. The event happened on the eve of the Duke of Edinburgh’s funeral. The next day, the Queen was seen mourning her husband of seventy-three years at Windsor Chapel alone.

According to a senior Labour strategist, it was this event above all others that destroyed voters’ faith in Johnson. Partygate had been ‘a slow-burn’ issue for voters, even though the Westminster bubble was ‘way more excited about it’. However, images of ‘the Queen sitting on her own’ at Prince Philip’s funeral, just as No. 10 staffers were nursing their illegal hangovers from the night before, was ‘the thing that really hit home’, the source said. ‘People still talk about it now.’9

Helen MacNamara, a top civil servant who worked as Deputy Cabinet Secretary and as a senior ethics official, even brought a 17karaoke machine to a leaving party for a No. 10 staffer at an event held in the Cabinet Office next door. ‘There was quite clearly stuff going on in No. 10 that was completely fucking unacceptable,’ one senior Tory recalls.10

As the torrent of revelations continued, the police launched an investigation – as did Sue Gray, the civil service’s go-to ethics guru. Her inquiry dealt with a succession of gatherings that took place over a twenty-month period, a number of which should never have been allowed to happen, she said. ‘There were failures of leadership and judgement,’ Gray wrote in her report.

At least some of the gatherings in question represent a serious failure to observe not just the high standards expected of those working at the heart of Government but also of the standards expected of the entire British population at the time … The excessive consumption of alcohol is not appropriate in a professional workplace at any time.11

Johnson, his wife, Carrie, and Sunak were among those who received fines in April 2022 for attending lockdown-breaking parties in Downing Street. Sunak thought seriously about resigning but was talked out of it, surprisingly for some, on the basis that quitting would put Johnson in an impossible position and potentially force the PM to go too. At that point, at least, Sunak didn’t want to bring down the Prime Minister.

LOYALTY

In an interview with Laura Kuenssberg, Sajid Javid spoke about how Johnson is incredibly loyal but that loyalty is conditional: ‘Do you 18back him in everything that he says and does? That’s the basis that you win that loyalty.’12

Johnson is unusually vulnerable to criticism. His thin skin, combined with an apparently uncontrollable impulse to try to charm anyone and everyone he meets, made life difficult in government for those whose job it was to implement policy. Civil servants and political advisers alike complained that he would change his mind, often repeatedly, and didn’t like to say ‘No’ to people. According to Cummings, Johnson once remarked that he liked the chaos that engulfed Downing Street because if nobody knew what they were doing, everyone would have to look to him for the answers.

Often, Johnson’s inconsistency was the trigger for relationships breaking up in his personal life. Carrie is his third wife and he has at least eight known children (four from his second marriage, one from an affair and three from his third marriage to Carrie. He declines to tell interviewers how many others there might be). In his political alliances, too, the pattern for Johnson has been one in which his allies often walk away, unable to tolerate the stress of working for him any longer. Those breakups are often kept quiet but sometimes burst spectacularly into the open.

One famous example is Michael Gove, who was Johnson’s campaign manager for the Tory leadership election in 2016. On the morning Boris was due to hold his launch event for the campaign, Gove announced he was running himself because he had concluded Boris was not up to the job. Years later, Johnson appointed Gove to the Cabinet, but when Gove joined the chorus of ministers advising Johnson to quit in July 2022, the Prime Minister angrily fired him instead.

When Dominic Cummings was thrown out of No. 10 in November 2020 after losing an ill-judged power struggle with Carrie over 19the appointment of an adviser, it was the final straw. After leaving government, Cummings made lurid claims about the scale of the dysfunction within Johnson’s Downing Street, turning from the PM’s chief ally to his most powerful and damaging enemy in the process. In one famous select committee hearing in May 2021, lasting more than six hours, Cummings called Johnson ‘unfit for the job’ and alleged that he had treated the pandemic as a ‘scare story’. In an interview with BBC journalist Laura Kuenssberg, Cummings disclosed that he and other former colleagues from the Vote Leave Brexit campaign had begun plotting to remove Johnson within days of winning the 2019 election. ‘He doesn’t know how to be Prime Minister, and we’d only got him in there because we had to solve a certain problem, not because we thought that he was the right person to be running the country,’ Cummings said.13

BETRAYAL

Johnson’s relationship with his party followed a similar trajectory, from veneration to repulsion. After the 2019 election victory, Tories feted him as the greatest political campaigner of the age, with even his one-time leadership rival George Osborne declaring that politics was entering the Johnson era.

By the first half of 2022, however, what little faith Conservative MPs had left in his leadership was evaporating in the heat of the spiralling scandal over lockdown-breaking parties in Downing Street. In June, he survived the test of a confidence vote, but it was a close call: 148 Tory MPs voted that they had no confidence in his leadership of the party, with 211 supporting him to stay on.

A month later, when Johnson could not get his story straight about what he knew of allegations of sexual misconduct against 20Chris Pincher, a government colleague and ally, a tipping point was reached. First, the civil service launched an attack, via Simon McDonald, the former top mandarin at the Foreign Office, who said No. 10 had not been telling the truth. For a former civil servant boss to accuse the Prime Minister of lying was an extraordinary moment. Some in Whitehall cheered McDonald, but others worried that a line had been crossed and reprisals against officials would follow. Then the resignations began.

At 6.02 p.m. on 5 July 2022, Health Secretary Sajid Javid quit, telling Johnson he’d lost confidence in his leadership. ‘I am instinctively a team player,’ Javid wrote in his resignation letter. ‘But the British people also rightly expect integrity from their Government.’ Later, in an interview with Laura Kuenssberg for the TV programme StateofChaos, Javid added, ‘I knew someone at No. 10 has been lying, again.’14

At 6.11 p.m., Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced on Twitter that he was also leaving, delivering a hammer blow to the PM’s authority. ‘The public rightly expect government to be conducted properly, competently and seriously,’ Sunak wrote in his resignation letter. ‘I recognise this may be my last ministerial job, but I believe these standards are worth fighting for and that is why I am resigning.’

At the time, Sunak’s shock decision was overshadowed by the drama of a government in disarray. But later it would be held against him by embittered Johnson fans in the party and the country, who blamed him for deposing their hero.

One after another, a succession of ministers followed Javid and Sunak out of government, most urging the PM to quit for the sake of the party and the country. For two days he refused, but the stream of resignations became a tsunami, with ministers quitting faster than Johnson could replace them.

During the messy, drawn-out endgame of his premiership, aides 21toyed with the idea of calling a snap election, to bully rebellious MPs back into line with the threat of punishment at the ballot box. But Cabinet Secretary Simon Case made clear to them that the Queen would be within her rights to refuse any request to dissolve Parliament to prolong the career of a Prime Minister who has lost the confidence of the House of Commons. The election threat melted away.

Reluctantly, on 7 July 2022, Johnson faced up to defeat and announced he would stand down, in a classically belligerent statement outside No. 10. ‘In the last few days, I have tried to persuade my colleagues that it would be eccentric to change governments when we are delivering so much,’ Johnson said. ‘But as we’ve seen at Westminster, the herd is powerful and when the herd moves, it moves.’ He added, ‘To you the British people, I know that there will be many who are relieved but perhaps quite a few who will be disappointed, and I want you to know how sad I am to give up the best job in the world. But them’s the breaks.’

For the third time in six years, the Conservative Party was thrown into the upheaval of a leadership election, while the country looked on once again at a government in chaos.

Four years and three Prime Ministers after the pandemic struck, it is clear that the Conservatives were never able to put themselves back together again and regain that elusive unity of spirit or the discipline required to deliver on a shared agenda for the country. Civil war inside the ruling Tory tribe had become a way of life.

Boris Johnson could have been Prime Minister for a long time. After winning a majority of eighty, he and his team were eyeing up at least a decade in power. But led by him, the Conservative government earned an unwanted reputation for callous hypocrisy during the pandemic, as well as for infighting and, perhaps most damagingly of all, for telling lies.22

Notes

1 Tim Ross, ‘Sajid Javid holds Boris Johnson’s fate, and the torch of Thatcherism, in his hands’, New Statesman, 15 September 2021, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/conservatives/2021/09/sajid-javid-holds-boris-johnsons-fate-and-the-torch-of-thatcherism-in-his-hands

2Laura Kuenssberg: State of Chaos, ‘Johnson’, series 1, episode 2, BBC Two, 18 September 2023

3 Interview, government source

4 Interview, senior official

5 Interview, Steve Baker

6 Interview, senior official

7 Interview, Tory aide

8 Interview, Tory source

9 Interview, senior Labour strategist

10 Interview, senior Tory

11 ‘Findings of second permanent secretary’s investigation into alleged gatherings on government premises during Covid restrictions’, Cabinet Office, 25 May 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1078404/2022-05-25_FINAL_FINDINGS_OF_SECOND_PERMANENT_SECRETARY_INTO_ALLEGED_GATHERINGS.pdf

12Laura Kuenssberg: State of Chaos, ‘Johnson’, series 1, episode 2, BBC Two, 18 September 2023

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

Chapter 2

Trussonomics

BALI

Liz Truss was on the beach.

The Foreign Secretary had not joined in the rush of resignations that triggered Johnson’s exit. She was staying at a villa in Bali, preparing for a G20 meeting that was expected to feature a showdown with her Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov. Walking up and down the shore, she held anguished phone calls with allies in London about whether to return to the UK or stay to finish the meeting. Eventually, her adviser Adam Jones had to tell her, ‘Liz, wake the fuck up and get back here.’1

In the leadership campaign that followed Johnson’s resignation, MPs whittled down a long list of candidates to a final two who would go to a run-off vote among Conservative Party members. After a slow start, Truss made it through to take on the ex-Chancellor, and the man seen to have ‘knifed’ Johnson, Rishi Sunak. She was an early favourite and consciously encouraged comparisons with Margaret Thatcher, both in her presentational style – including the white blouses and blue jackets she wore – and her agenda 24for unleashing growth with a slash-and-burn approach to taxes and regulation.

Up against that, Sunak – who is, in reality, a classic, small-state Thatcherite Tory by instinct – was always likely to seem cautiously centrist. Such was the transformation of the Truss brand since the 2016 EU referendum that she appeared the more strident Brexiteer, despite having campaigned for Remain. Sunak looked like a product of the pro-European elite, even though he had voted Leave. ‘Rishi didn’t offer anything to the membership for the future, except for credibility,’ according to one person who worked on his campaign. Credibility, it would turn out, can be an underrated quality, until it’s gone.

The summer leadership campaign was hot-tempered. Both sides traded insults and played dirty as they competed for the votes of thousands of Conservative Party grassroots members. Sunak repeatedly interrupted Truss during televised debates and was hit with the toxic charge of ‘mansplaining’ by her allies as a result. Polling, always a tricky business among the Tory membership, predicted a two-to-one victory for Truss, overturning the preference of Conservative MPs, who had backed Sunak.* In the end it was much closer than that, at 57 per cent to Sunak’s 43 per cent.

When Graham Brady, the chair of the backbench 1922 Committee of MPs, and the party’s chief election officer, declared Truss the new leader at an event on 5 September, she displayed what was to become a trademark of her short time in office and its aftermath: a blunt and stubborn refusal to accommodate those who see the world differently, including her defeated rival. Although Rishi Sunak was sitting only two seats away from her, separated by a single empty 25chair, Truss didn’t even acknowledge him, never mind shake hands for the cameras, as she strode up to the stage to claim her crown.

Truss’s decision in the days that followed to appoint a Cabinet drawn largely from her long-trusted loyalists and backers did nothing to win her new friends in the parliamentary party – which had preferred Sunak, after all – or to heal the divisions of a particularly nasty contest. ‘Liz only won 57–43 and yet she picked people for jobs only from her side,’ one MP recalls.2 When she needed their support a few short weeks later, it wasn’t available.

The calibre of those who found themselves around the Cabinet table was also questionable, Conservative MPs felt. One MP says, ‘She got in and appointed a whole load of people with minimal or no experience.’ Other senior politicians who had been top ministers suddenly found themselves out of a job, feeling isolated and disgruntled on the back benches.

Inside No. 10, Truss’s approach to hiring and firing and her combative, uncompromising style were given free rein. These qualities, which she had long displayed, contributed to her most devastating mistake: the so-called ‘mini-Budget’ package of unfunded tax cuts, which caused a market crash that almost brought the economy to its knees.

MORE HASTE

‘She is always in such a rush.’ If Liz Truss is one thing, it is ‘impatient’, according to one person who has worked closely with her: ‘She has always been like that. Everyone always says that about her.’3 Even the Queen advised Truss to pace herself, a suggestion the former PM has said she should have taken on board.

Truss’s fundamental economic analysis was that the UK, since the financial crisis of 2007–08, had suffered a decade and a half of 26anaemic growth. She came into office believing, according to aides, that the nation needed aggressive and potentially unpopular measures to revive stagnant growth rates and put the economy back on the right track. These included dramatically scaling back fiscal policy, with cuts to both taxes and spending on public services, and liberalising planning laws to get the country building again. Such medicine would not be popular, but the payoff, Truss believed, would be to recharge economic activity, return people to work and deliver what she promised during her leadership campaign: ‘Growth, growth, growth.’

It didn’t matter to Truss or her aides that she had no mandate from the wider electorate to deliver such a radical economic revolution. She’d won the party leadership; this was her chance and she had been planning to take it for some time.

CHEVENING

In the late 1950s, the 7th Earl Stanhope, who lacked an heir, was contemplating what he would leave behind at the end of his life. He resolved to make a gift to the nation of Chevening House, the estate near Sevenoaks in Kent that had been in his family’s ownership since 1717. Set in 3,500 acres of parkland, the 115-room stately home was built in 1630, reputedly to a design by Inigo Jones, and is now a Grade I listed building.

For the past forty years or so, the house has become the de facto country residence of the Foreign Secretary.† Truss had use of Chevening for government business and she chose to base herself there 27as she finalised her plans for power. In the three weeks before entering Downing Street, she gathered her team of advisers to plan a fiscal event, which quickly became known as the ‘mini-Budget’, that would serve as the big-bang moment to supercharge her growth strategy. Along with her political advisers, senior civil servants, including Cabinet Secretary Simon Case, were regular visitors, as Chevening became the Truss transition headquarters.4

Among the economic brains brought in to give the soon-to-be premier advice on her fiscal statement were veterans of the Vote Leave Brexit campaign and right-wing academics in the orbit of the Thatcherite think tank, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA). They included IEA fellows Julian Jessop and Andrew Lilico, as well as Gerard Lyons, who was Boris Johnson’s former economic adviser. Matt Sinclair, who cut his teeth at the Taxpayers’ Alliance, another free-market campaign group in Westminster, had become Truss’s principal economic adviser.

Lyons and Jessop wrote a paper for Truss aimed at supporting her growth agenda. It also contained a warning that would come to look prescient. ‘The markets are nervous about the UK and about policy options,’ they wrote. ‘If immediate economic policy announcements are handled badly then a market crash is possible.’5

THE STORM

On 6 September, Truss met the Queen and ‘kissed hands’ in front of a roaring log fire in Balmoral, the monarch’s estate in Scotland. Truss flew back to London and spent some time being driven around in her prime ministerial Jaguar, waiting for a break in the rain in order to arrive dry at Downing Street and make her first statement to the nation.

28When the moment came, she declared her mission to deliver ‘growth’ via tax cuts and reform – her slogan during the campaign. ‘I am confident that together we can ride out the storm, we can rebuild our economy, and we can become the modern, brilliant Britain that I know we can be,’ she said. ‘I am determined to deliver.’

Two days later, she unveiled the biggest state intervention in the energy market ever seen in the UK. With prices skyrocketing due to the war in Ukraine and global economic aftershocks from the pandemic, household bills were forecast to reach punitive levels the following month. Ofgem, the energy regulator, was preparing to raise the level of the energy price cap by 80 per cent from 1 October. It had already pushed the cap up by 54 per cent in April. Truss said she had to act, with typical household costs forecast to be £5,000 to £6,000 a year. On 8 September, the government announced the Energy Price Guarantee, worth an estimated £120 billion over the next two years. It was a vast commitment that would put a significant drain on public finances.

The energy policy was almost instantly forgotten. Later that day, Queen Elizabeth II died at the age of ninety-six.

It is hard to overstate the impact of the death of the Queen, after seventy years on the throne, on the functioning of the British state. While formally the sovereign has no power to determine the policies enacted by the government in their name, they remain the focal point of leadership for both elected members of Parliament and the permanent civil service, not to mention the criminal justice system and the armed forces.

It is central to the UK’s constitution, which relies largely on politicians behaving honourably, for there to be a figurehead at the top of it all to set the tone. The Queen was – and had to be – above politics. Politicians could never afford to try to be above the Queen. 29Johnson and Cummings, at various points, tried to play fast and loose with the convention that the sovereign must not be dragged into political games and found that the established way of doing things still had enough buy-in from MPs, and within the structures of Whitehall and the courts, to defeat them.

In the period of national mourning that followed the Queen’s death, all politics ceased, along with any discussion of economic policy. Whatever political dividend Truss might have hoped for from her truly radical measures to help families pay their energy bills was stifled at birth.

Truss has admitted struggling to meet the moment as a national leader. (Boris Johnson chipped in with his own video address to the nation via social media.) She has described feeling an overwhelming sense of grief at the death of the Queen and recalled asking herself, ‘Why me, why now?’

• • •

Truss always disliked big meetings. She preferred to hold working sessions with small groups of trusted aides. In her view, larger meetings tended to degenerate into performance art, with individuals taking their time to grandstand. When she took office, she tended to shut out most of her team, including some advisers she’d worked with for a long time. She did not even want to have a formal morning meeting each day, something that had been a Downing Street fixture for as long as anyone could remember. ‘After things went wrong, the meetings got bigger,’ one adviser recalls.6

Some of those around Truss believe the combined effect of her jetting around the country during the period of national mourning and preparing for the funeral, with the Queen lying in state, added 30to her isolation, leaving key advisers in the dark about the full extent of her mini-Budget plans.7

One person who felt invincible was Kwasi Kwarteng. He and Truss had been the closest of political friends and allies for more than a decade, ever since they both entered Parliament together in 2010. They had a shared economic outlook as free-market libertarians and had both been members of the Free Enterprise Group of Tory MPs during the Cameron–Clegg coalition. Neither had made much of a secret of their pro-growth, tax-cutting desires. But they did hold different views about how far to go and how fast.

TREASURY ORTHODOXY

One of Truss’s first acts, via her new Chancellor Kwarteng, was to fire the most senior civil servant in the Treasury, permanent secretary Tom Scholar. A highly experienced and respected official, Scholar found himself the wrong fit for Truss’s new agenda. Kwarteng immediately began looking for a replacement to deliver on her plan to rip up decades of what was disparagingly termed ‘Treasury orthodoxy’.

Scholar’s exit, which later saw him rewarded with a £335,000 payoff, robbed the Treasury of experienced leadership at a critical moment. Not only had the government just pledged a £120 billion intervention in the energy market but Kwarteng and Truss were at that very moment writing their ‘mini-Budget’. In preparation for their big-bang, go-for-growth moment, Truss also decided to shun the services of the Treasury’s independent forecasters, the Office for Budget Responsibility – another move that raised eyebrows (and government borrowing costs) in the City of London.

One person involved in the plan at the time describes the Energy 31