Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pampia Grupo Editor

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Spanisch

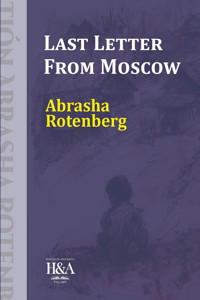

Last Letter from Moscow is a captivating narrative that combines the pace of a thriller with the depth of historical memoir. Abrasha Rotenberg, born in Teofipol, a village in Ukraine within the former Soviet Union, was a direct witness to some of the most tumultuous events of the 20th century: the Russian Revolution, communism, Nazism, and later, Peronism and the establishment of the State of Israel. His life is an emblematic journey of exile, filled with challenges and contradictions. From his childhood under the newly established Bolshevik regime, to his first migration to the city of Magnitogorsk in the Ural Mountains—where his young eyes witnessed Stalin's grand experiment in industrialization—and his experiences in Moscow, the epicenter of Soviet power, the author recreates a dizzying universe. The story of the protagonist, a de facto orphan, takes a dramatic turn when he manages to leave the Soviet Union with his mother, heading to Buenos Aires to reunite with a father he knew only through photographs. Decades later, while exiled in Spain, the author and his wife, Dina, meet a Spanish couple in a small town in the Sierra de Madrid. During this casual encounter, he shares fragments of his life, now enriched with new perspectives and challenges. Two letters shape the course of events: the first, in 1947, delivers the devastating news of the narrator's family being murdered by the Nazis. The second, twenty years later, initiates a correspondence laden with suspicion and tension. This epistolary exchange, alongside the fraught relationship between father and son, creates a tense atmosphere that culminates in an unexpected and striking conclusion. Last Letter from Moscow is a story that explores the weight of memory, the pain of uprooting, and the scars of the past, while reflecting on the complexities of identity and human relationships. A must-read for those seeking to understand the profound changes of the 20th century through the life of a singular author.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 450

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Last Letter

From Moscow

Last Letter

From Moscow

Abrasha Rotenberg

Rotenberg, Abrasha

Last letter from Moscow / Abrasha Rotenberg. - 1st. ed.

Buenos Aires : Hamlet y Asociados, 2024.

eBook

ISBN 978-631-90850-2-0

CDD A860

©2024, Abrasha Rotenberg

©2024, Hamlet & asociados

Published under the Hamlet & asociados® imprint

Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Translation supervision: Emilia Novello

Editorial coordination: Marcelo Caballero

Collection design: Maitreya Art & Design

Layout: Maitreya Art & Design

1st edition: December 2024

ISBN 978-631-90850-2-0

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, rented, transmitted, or transformed in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, digitization, or other methods, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Violation of these terms is punishable under Laws 11.723 and 25.446 of the Argentine Republic.

abrasharotenberg.com

To my grandchildren:

Martín Páez Rotenberg,

Mateo Rotenberg García de Piedra,

and Valentina Rotenberg García de Piedra,

So they may learn about one of their roots, share it, and never forget it.

Prologue

This is a book of many readings, layered one upon another. The plot recounts a singular human journey shaped by multiple exiles, uprootings, and hardships. But these splendid pages are written within a wider margin than what is printed. In that margin, the most important element is time.

The theme of Last Letter from Moscow is autobiographical, yet it is far removed from any narcissistic settling of accounts. It is a constant inquiry into being and non-being, truth and memory, life and death, the figure of the father, and the book itself. It does not merely symbolize the expulsion of the millions upon millions of people around the world who have suffered and continue to suffer persecution, hunger, poverty, discrimination, and humiliation. Instead, the author measures himself against these realities and projects the allegory of a moral conscience.

The music of the book lies in the symphonic development of several interwoven stories, in reverberations, halos, or incandescences that speak through their silences. Perhaps the best way to conceal a destiny is to recount it. The probable narrative highlights through its contours everything left unsaid, everything it cannot fully articulate—those secret movements that bear witness to the fact that silence—or oblivion—is a powerful shadow, and at the same time, a field that opens the path to sensitive memory and the truth of the heart. Something exceptional happens with this book: what has been read becomes part of the reader’s own experience.

Astute critics will highlight the aphorisms that condense vast reflections into a few lines, or the tireless scrutiny of the meaning of things by someone who knows that in life, everything has its meaning, or the Jewish humor that weaves through the text as proof that it is possible to laugh at the world, including oneself as part of it, with weary indignation. But above all, this work brings together a mastery of style and emotion over prolonged suffering, an analysis of the moral essence of the time we live in, and an exploration of identity as a rejection of servitude. That is no small feat.

Juan Gelman

Editor’s Preface

Abrasha Rotenberg presents us in Last Letter from Moscow with a work that not only recounts the crucial moments of his life but also delves deeply into the great dilemmas of his time. In these pages, we encounter a story that traverses revolutions, exiles, and reunions but, above all, explores the meaning of belonging to a world in constant transformation.

The author’s life begins in a small village in Ukraine, in the former Soviet Union, where Jewish traditions coexisted with the early stirrings of the Bolshevik Revolution. Through his eyes, we bear witness to a turbulent 20th century, from the industrialization of the Urals to his migration to Buenos Aires, a distant destination that embodied both hope and uncertainty. Each stage of his life is marked by a continuous need to adapt, reinvent himself, and build new foundations amidst overwhelming changes.

What makes this work unique is not only the intensity of the events it recounts but also how it weaves a narrative that combines the precision of testimony with the emotional depth of lived memory. At the heart of this story are two letters that forever shaped his life. The first, devastating, reveals the loss of his family at the hands of the Nazis. The second, decades later, initiates a dialogue filled with silences, tensions, and unspoken truths, where father and son confront the wounds of the past.

Beyond the historical events, Last Letter from Moscow is a reflection on the human condition, showing us the complexity of living at the crossroads of worlds: the legacy of tradition versus the demands of modernity, and the need to remember contrasted with the drive to move forward. On every page, the author questions and redefines his identity, composing a narrative that resonates with anyone who has sought a place to call home.

What motivated me to work on this anniversary edition was the extraordinary depth and authenticity with which the author tells his story. Although profoundly personal, his narrative echoes universally, masterfully connecting individual experiences with the great events that shaped the 20th century. From the first pages, I was captivated by his ability to weave together, in a single thread, daily experiences and historical tensions, exploring not only the facts but also the emotions, contradictions, and dilemmas that defined his life.

As an editor, I have always sought projects that not only tell a story but leave an indelible mark on those who read them. This anniversary edition of Last Letter from Moscow not only fulfills that expectation but enhances it. In a world as turbulent as ours, Abrasha Rotenberg’s testimony is incredibly relevant. His reflections on exile, identity, and memory engage with the challenges of our times.

Marcelo Caballero

First part: Facts

The Call (Buenos Aires, December 22nd, 1965)

The distant ringing of a telephone began to wake me. I was dreaming about a confusing episode from my childhood, and I clung to the sound as if it were a lifeline to escape the nightmare. I half-opened my eyes and made out the outlines of the room, illuminated by the dim light of dawn. My wife was asleep beside me. I felt uneasy; an early morning phone call could only bring bad news and I wasn’t in any condition to handle it.

That afternoon, our optimism had been rekindled, and we agreed to let my father undergo a shock treatment. For a week, a healing master had been encouraging us with the words we needed to hear: his health was not as broken as we had thought, and the process could be reversed if certain conditions were met. The most basic one, no professional or even family interference was allowed. In two weeks —the healer guaranteed it— my father would recover. A miracle? No: experience and knowledge. The effects would be noticeable immediately. The treatment involved a considerable financial investment, which he justified.

“It’s worth the effort,” he declared, without caring for our opinion.

A wall of skepticism stood against his predictions, starting with the opinion of the person most affected, which wasn’t based on scientific considerations. When I told my father that the healer guaranteed his recovery, he responded in Yiddish with a popular saying:

“Er vet mir helfn vi a toitn bankes.” (He’ll help me like cupping helps a dead man).

That was his only comment.

For the oncologists —even for our cousin, the doctor— my father was already sentenced, and we should spare him unnecessary suffering. Science excluded and condemned miracles.

We discovered the healer through a devoted patient who had overcome the ravages of a similar illness with his treatment. After two consultations, we found ourselves torn between anxiety and hope.

If that patient could testify to the viability of recovery, why were we having second thoughts?

We had trusted oncologists, surgeons, and specialists, accepted countless futile attempts that raised our expectations only to deepen our despair, and suddenly, fate offered us an encouraging chance: why reject it? What did we have to lose?

We decided to cling to hope because traditional medicine, with all its certainties, led to an irreversible outcome.

My cousin, the doctor, felt offended by the excessiveness of my optimism, as she interpreted it as a veiled criticism of her professionalism.

I was suspicious of this unprecedented treatment that no one had heard of; any responsible scientific discovery would reach the medical community and not be confined to a privileged circle.

Little was known about this man’s practice, and nothing about his methods. We had to act with caution because charlatans —and swindlers— were plentiful. Even in medicine.

“Your father has, with any luck, a few weeks left. I don’t believe in miracles,” she snapped, irritated, trying to mask her resentment.

I felt outraged by such certainty. My cousin’s arrogance and her death sentence stood in stark contrast to the calm the healer gave me: I was convinced he would save my father. I needed to believe in him.

We hadn’t slept in weeks. That night, I felt the need to reward us to celebrate that hopeful expectation. I chose to savor the subtle mysteries of a bottle that a friend, with whom I shared a passion for Scottish liquids, had given me.

“It’s a wonderful whisky,” he declared with the authority of experience, “a single malt: aged eighteen years. You have to drink it neat. None of that ‘on the rocks’ stuff. That’s for beginners.”

I took his advice without considering the consequences. By the second glass, I had forgotten my sorrows. By the third, even my name. I needed it.

Dina, my wife, who had shared my anxieties for months, decided to join me.

A few minutes later, we were both fast asleep. Some hours later, that ringing phone began to disturb me.

Dazed, I clumsily picked up the receiver. My head was buzzing, and I felt slightly dizzy. Before I could respond, I heard my name:

“Abrasha.”

“Yes. Who is this?”

“Mom.”

I involuntarily shuddered. It surprised me that she was speaking to me in Spanish. I answered in the same language, with feigned calm:

“What’s wrong, Mom?”

A broken voice reached me, the trembling voice of a stranger.

“I need you to come. Dad’s not feeling well.”

“Did you tell Hadassa?”

Hadassa was our cousin, the doctor. She lived in the same building, just a few floors up.

“Hadassa is here with us; she asked me to call you.”

“I don’t understand. Just this afternoon, the healer…”

“Forget about the healer and don’t waste time, come quickly.”

“And Rodo?”

Rodolfo, my younger brother, also lived in the same building.

“He’s here with me.”

“I’ll be there right away.”

“I’ll wait for you.”

Before hanging up, I heard him say, “Please, drive carefully.”

I couldn’t help but smile.

Dina was sleeping, and I decided not to wake her. We had shared so many adventures, woven together a love story that still endured, enjoyed the birth and tenderness of our children, suffered through misfortunes, unexpected falls, and gratifying achievements. I was fortunate to lean on her strength and count on her support during my downfalls, which were not few.

At that moment, I had to face the scene I had imagined so many times and always dreaded. It was about my crucial scene, the one that would inevitably come.

I turned on the light. Dina began to wake up.

“What’s going on?” she asked, surprised.

“Mom called. Dad’s not doing well. I’m going to see him.”

“I’ll go with you.”

“Not now. Stay with the kids. I’ll call you later. If necessary, I’ll ask you to come. In the meantime, rest.”

“I want to go with you.”

“Maybe later.”

“Is he very bad?”

“I don’t know.”

“I want to say goodbye.”

“I’ll call you later, I promise.”

The sun was already rising on that warm December morning. As I drove at a reckless speed, I recalled some of the conversations I had had with my father. During the long nights of his convalescence, we had spoken for the first time as adults. It was then that I began to discover him, and the more I got to know him, the more it pained me to see how his face became more transparent, and his eyes—those clear, hostile eyes that had intimidated me for years—started to fade like a sunset. I thought—felt—that those late-night conversations had illuminated the history of our bond, giving it a meaning. I needed them to understand myself and my fate, but death was getting ahead of me.

Suddenly, I remembered a poem by Chaim Nachman Bialik, that powerful Israeli poet, who described death, in Hebrew, with astonishing simplicity:

Haiá ish, veeinenu. (There was a man—and see: he is no more).

Was the perception of death really that simple? To be, and then no longer be—is that the difference? Does the pain lie in the idea of no longer being or in the there was that gave it a meaning? Because if absence were temporary, our suffering would lessen, but the word was elevates the loss to the level of the irretrievable.

How can we bear it? How can we not remember that we are condemned to the same fate?

We start from absence and to absence we return; in the brief journey, we burden ourselves with resentment, darkness, and a little love. Resentment and darkness dominated me for decades, blinding me with anger toward that stranger, my father.

And now, I was about to face his death, a fate I had wished upon him so many times for my temporary relief and later regret.

I couldn’t suppress a sob. I was crying for a man I had only begun to discover, after hating him for so long.

I sped up because I was afraid of arriving too late.

“This is the end,” I repeated as I wiped away my tears.

The dawn timidly broke. I remembered that I had also met my father during a warm early morning, during a conflict that shaped the course of my life, filling it with sorrow and, perhaps, with a dark way of loving that I only understood much later.

More than thirty years had passed since that morning. I often managed to reconstruct that encounter, to piece together all the faces, gestures, and words: a perverse exercise in memory that forced me to delve into the depths of my wounds to demonize the one who had inflicted them.

As I approached the building where my parents lived, I recalled some scenes from that November morning in 1933.

I saw myself peering from the deck of a ship at the confusing panorama of a Buenos Aires that awaited me with its mysteries. In the distance, the indistinct silhouettes of a ghostly port emerged, illuminated by the timid light of dawn. I also remember how, as the streetlights slowly went out, we began to see the true face of the city.

I both longed for —and feared— that encounter with my father.

I couldn’t have known that thirty years later, perhaps in just a few hours, I would lose him for good. I felt an immense sorrow and, at the same time, frustration: there was so much affection left to discover and unfinished conversations to complete, but we were running out of time.

Trembling, I opened the door to the apartment. No one came to greet me. I realized that I had arrived too late.

Fatherless child

Ukraine - Soviet Union, 1930

I was born in Ukraine, in a small town with two names, a toponymic schizophrenia that perhaps shaped my identity. In Russian or Ukrainian (or, to be more precise, in Greek and Latin), it is called (even today) Teofipol; in Yiddish, Chón.

A small village lost in the Slavic geography having a Greco-Roman name seems more like an enigma than a rarity. With a generous semantic investigation (Teo, God in Greek, and fipol, a combination of filius—son in Latin—and polis—city in Greek—), we could conclude that I was born in the city of the son of God. Did that fact imply a destiny for me? We’ll never know why it didn’t materialize; perhaps it was because my mother didn’t speak the classical languages and wasn’t aware of the opportunity being presented to me. Consequently, my mother didn’t prepare me for a redemptive task and was content with the early signs of genius she believed she saw in me, just after I was born. Son of God, maybe not, but “With that head? He’ll undoubtedly be a minister.”

I don’t understand why her predictions didn’t come true.

When I came into this world, Chón had fewer than a thousand inhabitants, most of them Jewish. My grandparents and ancestors had lived in the Russian Empire for centuries, although their deeper roots trace back to the domains of Charlemagne, and their ancient origins to biblical lands—if not further back to Ur of the Chaldeans. Under Slavic rule, they endured the harsh rule of the tsars, bloody pogroms, restricted residency zones, prohibitions against travel, education, or practicing a liberal profession, and countless other limitations. The tsars often honored them by conscripting them into the army for decades or even for life. In short, they were condemned to a humiliating, bleak, and unstable existence, without a future or hope.

Despite their precarious situation, they survived in small villages scattered across the empire, practicing poverty as a forced trade while longing for the arrival of the Messiah, who would redeem them by returning them to the Promised Land.

Overwhelmed, they shared with the Russian people the cruelties of an authoritarian regime and the injustices of an economy frozen within a backward social order.

The law denied them access to land ownership in an agrarian economy. With few exceptions, they had no choice but to engage in small-scale craftsmanship, bartering, or trading primary goods, to practice despised trades, or to live off nothing and practice piety by following biblical commandments and the teachings of the rabbi, who was as ignorant and unprotected as his congregation.

My grandfather had attained a privileged position in that bleak universe. I learned—according to family legend—that he had amassed “a small fortune” during the time of the tsars by trading cattle.

Years later, I found out what was left of his fortune: three cows, two horses, a house, and a tough character.

My grandfather was not beloved by his neighbors, who considered him sullen, skeptical of religion, and never a practitioner. He was fond of a good measure of vodka (or two, or more), unpredictable, and often excessive in his reactions, even in his spontaneous—though infrequent—generosity. His presence had the effect of a thunder on a clear sky. His children, besides respecting him, feared him. None could endure his gaze.

My grandmother, on the other hand, came from an educated family and was his complete opposite: tender, calm, passionate about reading and mathematics, eager to stay informed, attentive to political events, and always open to dialogue. She was an unusual character in a small-town environment that was ignorant, prejudiced, and prone to visceral reactions.

Despite their opposing personalities, they formed a solid family unit. My grandparents had six children; the youngest was born at the same time as their first grandchild.

In general, the Jews of Chón spoke Yiddish and stammered Ukrainian with their gentile neighbors, except for my grandmother, who also spoke fluent Russian. I never knew why or how she learned it, nor did I understand where her passion for literature and the exact sciences came from.

In Chón, as in all small towns, there was no lack of a church or a synagogue, but prejudice and mutual distrust loomed large. It was a hostile world that often erupted against the Jews: the gentiles would destroy (or seize) their property and their lives, but they did not dare to confront their real oppressors—the tsarist regime and its institutions.

Often, the authorities would encourage or organize pogroms to soothe the people’s anger and redirect it toward the weakest.

The political situation became untenable during the outbreak of the Great War (1914–1918). The structures of power began to collapse, and a revolutionary, justice-seeking human wave imposed its will with blood and fire.

The Messiah had arrived, though, contrary to expectations, he wasn’t born in Teofipol but in a revolutionary movement inspired by the philosophy of a descendant of converted Jews named Karl Marx. In a series of events that convulsed the world and changed the Russian history, as well as the course of mankind, the astonished inhabitants of the small town of Chón experienced a catharsis. A new order was born, bringing about a profound change in the structures of the country and its stagnant society.

In the name of the revolution, many Jews were discriminated against because, ideologically, they were seen as a hindrance due to their roles as intermediaries and small traders. Only productivity held social value, to the point where writers were considered “engineers of the soul.” Their marginalization was driven by economic and political considerations, not racial ones, since antisemitism was formally outlawed by the new laws, though never eradicated, as it was a deeply ingrained sentiment among the people. In fact, some laws that indirectly affected the Jewish population came from their own brethren—revolutionary leaders whom Stalin would later eliminate through drastic purges that culminated in anti-Semitic fabrications like the fabricated “Doctors’ Plot” conspiracy.

My grandfather and some of his sons were classified —under the new policy— as parasites, enemies of the proletariat, incapable of integrating into a revolutionary society of peasants and workers. Our family was divided between revolutionaries and parasites, and among the latter was my father.

A few versts from Teofipol (about twenty kilometers), there was a small village without any toponymic peculiarities, as it had only one name in both Ukrainian and Yiddish: Zapadenietz, my maternal family’s village.

To visually imagine a shtetl (Yiddish for small town, diminutive of shtot, city), one must turn to the pages of Sholem Aleichem and the paintings of Marc Chagall—though without including brides in the clouds or fiddlers on rooftops. Reality was much grayer and more monotonous.

I remember Chón, and I remember Zapadenietz, even though I was a child when I left them. Zapadenietz was an even smaller village than Chón, with fewer inhabitants, an island in the middle of the countryside. Along dirt roads (and mud in the winter), a few small houses stood, built of “adobe and sadness,” as the poet Itzik Manger once put it. In Chagall’s view, and in my memory, they appeared dilapidated and on the verge of collapse, but inside they were warm and welcoming. The small village abruptly and seamlessly opened up to the countryside: at dusk, we were surrounded by the songs of the peasants returning from the harvest.

Chón, on the other hand, displayed solidity: a single street divided the town into two areas, where a few houses surrounded by orchards stood out. The street ended at a small bridge, below which a stream flowed, where we used to swim in the summer. After the bridge, a road framed by wheat fields stretched out.

My grandfather’s house was on the outskirts of the town, not far from the bridge and the river. It was sturdy and surrounded by an orchard. In the stable, a cow chewed its cud next to a horse, which my grandfather cared for with tenderness—a sentiment he withheld from his fellow humans.

Across from my grandparents’ house lived a Ukrainian family: a grandfather, parents, and two children. The girl, two years older than me, was my playmate. Her brother—about ten years old—always bothered us. Should I confess that I hated him?

By the door of our family home, sitting as still as a statue, my grandmother would lose herself in the world of her books for hours (and days). I remember her with her head buried between the pages, in an act of devotion that could only be understood by her thirst for knowledge and her nearsightedness.

She had no interest in domestic chores or the demands of her husband. While chaos reigned in the house, my grandmother, unfazed, indulged in her obsession with reading. Sometimes she needed to share her perplexities, and if she lacked a suitable conversation partner, she assigned me that role. I would listen to her stories, often beyond my comprehension, but always filled with charm and mystery. I was fascinated by her style and the happiness on her face as she described the contents of a book, or a chapter, or even a single sentence. Yet often, she would simply return to her reading without offering any explanation. Frustrated, I would ask her to continue or to teach me how to read, but she would reply:

“You’re too young. You’ll read when you’re older. For now, just sit and watch how I do it; that way you’ll learn.”

Sometimes she took pity on me and taught me a few letters of the alphabet. With her, I learned to decipher words and scribble them. Those were the beginnings of my later hunger for reading.

Despite her firm demeanor, my grandmother could also give in to moments of tenderness. When she sensed my struggles or my loneliness, she would put aside her books to talk with me and protect me.

In Zapadenietz, there were no grandparents, only uncles. The grandparents had died young, leaving six unprotected orphans. The older siblings helped raise the younger ones. In difficult times, they fought for the survival of the family, and without much fuss, they managed to preserve and strengthen it.

My mother’s family came from a lineage that valued knowledge, kindness in interactions, and respect for others. There was no room for violence or authoritarianism.

When the Revolution broke out, most of the siblings, now teenagers, were able to study. Education became a top priority for the government, a monumental task aimed at transforming the mindset and habits of a rigidly structured society. However, as the revolution became institutionalized, its projects began to lose their original purpose, ultimately betraying their initial goals. The revolutionary changes had taken root in the youth, who enjoyed privileges unimaginable before the revolution; my mother was able to attend a state school that had been inaccessible to Jews during the tsarist era. She spoke Ukrainian and Russian fluently, and her education enabled her to work in what we now call the service sector. She had a basic grasp of Yiddish, and her knowledge of Judaism was limited to memories of a few holidays that the family had once celebrated.

I grew up in an environment where Russian or Ukrainian was spoken, and Jewish traditions were replaced by revolutionary fervor. I never felt different from the other children, nor did I have much awareness of my Jewish identity, though my family, especially on my father’s side, retained certain underlying characteristics.

My mother was only able to study for a short period because, as the eldest sister, she had to take care of her younger siblings. Some of them went on to attend university and later worked as educators, government officials, cooperatives members, and career military officers.

My mother’s brothers joined the Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, and later the Party. I remember them during the May Day parades, marching alongside workers and peasants or riding on horseback. They were dressed according to the revolutionary aesthetic, images of which were multiplied in propaganda posters: white shirts and red scarves fluttering in the wind. Those smiling faces represented the revolutionary youth, the owners of the future, as my uncles’ generation was often described. But the revolution was only celebrated on a few days of the year. The rest of the time required effort, fatigue, hunger, mud, and a sadness that even the exuberant celebrations couldn’t hide.

I felt proud when my uncles marched in the celebrations because they looked like the heroes on the posters: they were handsome, imposing, and spotless.

What kind of work did my family from Teofipol do, and how did they survive under the Bolshevik regime? The two older brothers—one of them my father—had only attended elementary school, had no trade, and were therefore condemned to earn a living as small intermediaries in an area with no future: commerce, which the Soviet State aimed to socialize, along with the means of production.

Teofipol was located near the Polish border, historically vague, conflict-ridden, and above all, porous. I suspect that the brothers—each on their own—often crossed it without going through the formal customs process, thus earning not only a few rubles but also a certain reputation as sharp merchants. My uncles and my mother used to mention that, by the age of seventeen, my father was already respected as a prosperous businessman. That was until the Revolution was institutionalized, and his decline began.

My uncle Israel —whom they called Srulek—, the eldest of the brothers, married a neighbor from Chón who did not meet my grandfather’s social and aesthetic expectations, which further strained their already tense family relationship. Since he lacked the means to support his family, had no prospects of finding them in the communist society, and could not turn to my grandfather for help, he decided to emigrate to Poland with the intention of settling there, but without any success. Driven by bad luck and with no future in sight, the couple decided to move to Argentina, where his brother-in-law, his wife’s brother, was living and willing to take them in. They had two daughters born during their time in Poland. Srulek left for Buenos Aires with his family.

Once private property was reduced, the means of production were socialized, political controls were strengthened, the corrupt Tsarist governmental organs were purged, and the revolutionary ones consolidated—despite the devastation caused by both external and internal wars that dragged on for years—, the Bolshevik regime managed to take root. During the shifting course of that process, my grandfather and my father managed to survive intermittently.

Habits and ways of life do not change radically just because revolutionary laws dictate it. They require time and a prolonged emotional process to adapt to new circumstances; after a period of contradictions, ups and downs, advances and retreats, a permanent balance is eventually reached.

As a consequence of the painful economic situation, the government relaxed its initial socializing policies and authorized (or tolerated) the temporary practice of private economic activities. That shift, which was implemented over several years, was called the New Economic Policy (NEP), whose supposed leniency the surviving peasants would later remember with nostalgia.

My grandfather was not stripped of his house, his cows, or his horses, and my father was able to engage in his mercantile activities with excellent results, attaining a comfortable position in an unstable world.

During one of these periods of prosperity, he met the woman who would become my mother.

I can sense the reasons that might have sparked my mother’s interest in the man who would become my father: the image of a young, successful man, full of projects and ambitions, talkative and triumphalist, made an impression on her. Could what emerged between them be defined as love? Impossible to know at their twenties; unnecessary to question later. A few months after meeting, just after turning twenty-one and despite some reservations from her maternal family, they married and enjoyed a period of circumstantial prosperity. Settled in a comfortable home, they lived as privileged people in an unreal micro-world.

Two years later, the fiction began to unravel: commercial activity was restricted, and the Criminal Code introduced some unsettling articles. The NEP fell into crisis, and Stalin began to dig its own grave, eventually burying it at a high cost paid by the peasants. Since my father lacked the skills for other trades and had no useful profession according to the State’s philosophy, it didn’t take long for him to be classified among the parasites—socially and politically undesirable individuals. My father realized that if he didn’t change his line of work, he would end up in Siberia.

Income dwindled or disappeared. The couple had to give up their house and move into my grandparents’ home. That’s where I was born, on May 4th, 1926.

A year later, my father decided to cross the porous Polish border in search of a future in that country. He arrived with empty hands and empty pockets: he had no trade, no language skills, no passport, and no means. He relied on his ambition, youth, and good luck. He wandered through Poland and other European countries, but he couldn’t settle anywhere. With no prospects, he decided to head to Buenos Aires, where his brother Srulek lived.

I remained under the care of my mother at my grandparents’ house. The country, Chón, and our situation were going through a bitter period, though I didn’t notice it. Not even the sight of hunger in my childhood helped me understand the tragedy we were living through: collective poverty acted as a great equalizer, leaving no room for comparisons. We were miserable, though we didn’t realize it because we lacked points of reference, and besides, the regime convinced us otherwise through education and propaganda: it was worth sacrificing to build the future, the glorious communist future. The future took its time to arrive, and when it did, no one could recognize it.

My father’s younger brothers were able to study up to the university level. From Chón, they moved to Kiev, Odessa, and Moscow to integrate into the new communist society. Beautiful rhetoric, which also shaped my education. But reality didn’t unfold according to ideological projections or the slogans about the future. A decade later, the latent European conflicts erupted, and the shadow of Nazi Germany darkened all plans. The future was cut short along the way.

Not all my uncles embraced the revolutionary process; there were exceptions. My father’s only sister married an Orthodox Jew who secretly held onto his religious practices, even when official policy condemned them. It was a Judeo-Ukrainian version of Iberian crypto-Judaism, daring to defy the red inquisition. Three times a day, hiding, he fulfilled the traditional rites: he prayed while simultaneously cursing the communist regime for its atheism. I remember how he overwhelmed me with his fears and tried to pass them on to me as an inheritance. Yet, in his own way, he also showered me with affection.

Only when I was almost eight, I met my father. I was raised by aunts, uncles, and grandparents who sheltered me but couldn’t replace his presence. I was a spoiled and melancholic child who grew up freely within a trap. Despite everything, I suspect I grew up privileged. I realized this years later, at the cost of loneliness and estrangements.

Family photos

Soviet Union, 1930-1933

According to family legends, when my father slipped away from Teofipol and the communist regime, he solemnly swore that, within a year, he would reunite the family, though he didn’t specify where in the world that might be, because he didn’t know.

Hugging my mother and planting loud kisses on me, he begged us to trust his promise. I don’t remember the scene—I was around a year old—but my mother and my uncles described it to me often, and it always moved me to hear it.

My father failed to keep his promise for various reasons, most of them beyond his control. For years, he maintained a long but intermittent exchange of letters with my mother, often including photographs. The irregularity of the correspondence can’t be entirely blamed on him, as there were political reasons that justified it: the frequent contact with a defector living abroad could lead to the dungeons of the GPU, the State Political Directorate. It was best to act with caution.

From an early age, I realized that any mention of my father caused tension, especially within my mother’s family. It seemed as if they were trying to erase him from my life through silence.

But I wanted to know how he was living so far away from us and when and where we would reunite. I needed to convince myself—and others—that, like all children, I had a father too.

When one of his letters arrived, my mother grew anxious, and as she read, it seemed like she was reliving a nightmare, with each paragraph foretelling misfortunes. After reading it (always accompanied by a few tears), her face would relax, while I, restless, tried to find out what it said. I suspect that my mother reworked the text for my enjoyment. She had, besides experience, a natural talent for keeping me entertained. The letters were sprinkled with anecdotes about Buenos Aires and stories about my father, whose virtues she generously highlighted. My father would insist on how much he missed us and promised that we would soon reunite. He had a surprise in store for me, though it was so often repeated that it ceased to be one: a house with a room just for me.

The dream of that room of my own, which my eagerness glorified, became the driving force behind my travel fantasies. I boasted about that room to my friends and relatives, who doubted its existence. People shared rooms with no other option than to live in overcrowded spaces. An exclusive room? Impossible.

I couldn’t understand what my father did for work in Buenos Aires, but it had to be something important if he could afford such privileges.

Sometimes I would fantasize about his image. My mother described him as robust, tall, with pleasant features, inclined to jokes, and with an excellent disposition. My maternal uncles, however, reduced his stature to more modest levels and his humor to a constant melancholy, interrupted by unpredictable bursts of festivity. I chose my mother’s version: I preferred to see myself as the son of a titan. In my games, I would draw my father with a handsome face and, above all, an athletic build. A true hero. A distant and unreachable hero. My grandfather, his father, never mentioned him. My grandmother used to write him a few letters, where — as I learned as an adult — advice and reproaches were never lacking.

One time —I must have been four years old— my mother showed me a photo.

“Do you know who this is?” she asked, trying to sound mysterious.

I didn’t hesitate to answer:

“Dad, that’s my dad.”

What had I discovered? The image of a young face, with clear, sad, and tired eyes, and an incomplete smile, hinted at to satisfy the photographer’s demands but incapable of breaking out naturally.

I’m describing with adult words the effect the photo had on me: my father didn’t resemble the giants I had drawn at all, though his face did have some features that reminded me of Uncle Arón’s, who wasn’t a titan — just an engineer.

Two years later, while staying at my aunt’s house, I stumbled upon a full-body portrait that left me bewildered. I suspect my mother had decided to hide it from me. It was a photograph taken after the first one: a stern face, with a severe gaze where resignation seemed to have replaced sadness; tightly pressed lips, as if to silence bitterness; disheveled hair, and any trace of youthfulness completely gone. But the face was just a fragment of the picture. The rest seemed surreal: over my father’s shoulders was a mound of clothes and other goods, the weight of which he appeared to carry with dignity. He wore a shirt with large sweat stains prominently showing. In the background, a cobblestone street, empty lots, and low houses could be seen, along with the silhouettes of a few children watching the scene from a distance. It was clearly a hot day. This was the first street in Buenos Aires that I ever saw, the first glimpse of the city where my father lived and waited for us.

Regarding the photo, it raised some questions for me. The main one: What was my father doing with that load on his shoulders? My mother was right—only a strong man could carry it. But it wasn’t a demonstration of strength, rather an ambiguous and mysterious situation. My aunt Brantse couldn’t find a convincing explanation for the meaning behind the strange load.

“It’s capitalist customs we don’t understand,” she remarked, repeating a cliché her husband, a Party member, had instilled in her. I wasn’t satisfied with the answer, but I didn’t press further. Years later, I was able to uncover the mystery.

My mother proudly showed me the third photo. We were in Moscow, a few months after moving to the capital. She held the photo up in front of my eyes, with a smile that betrayed her satisfaction:

“Do you recognize him?” she asked, waiting for my reaction.

I could make out, in the foreground, a man sitting on a small chair. Then, a dimly lit room; on the wall, a window was barely visible, covered with a curtain. The man was dressed in a dark suit, white shirt, and instead of a tie, he wore a bowtie. I assume, at the photographer’s direction, he was seated in a forced posture meant to highlight, through dim lighting, the features of his face and a gaze directed at the horizon. Although he seemed to be making an effort to remain still, barely breathing, his presence filled me with admiration. My joy didn’t last long.

As I looked more closely at the photograph, I discovered that my father was sitting with his legs crossed. While his left hand rested on the arm of the chair, his right hand—evidently trying to be hidden between his thighs—was revealed as a mutilated, fingerless stump.

The discovery unsettled me so deeply that I was paralyzed. My mother smiled and looked at me, waiting for a response—she needed me to share in her pride. I couldn’t utter a word. Somewhere in the pit of my stomach, I felt an unpleasant sense of rejection toward the amputated hand. It was unfair, but I couldn’t control my feelings. Finding out that part of my father’s body had been severed filled me with such horror that I didn’t dare to mention it to my mother, nor did I try to find out how, or by whom, or under what circumstances it had happened. I felt that I would never be able to bear living with a cripple, even if it was my father and even in a city like Buenos Aires. I felt ashamed of myself instead of feeling compassion for him.

“Doesn’t he look like an artist?” my mother insisted, unaware of my feelings.

“Yes, an artist,” I repeated mechanically.

My mother looked at me, puzzled. She couldn’t understand what had come over me or the reason for my reluctance. I remained silent, muttering my disappointment. At just seven years old, life had laid a trap for me—an anguish I couldn’t share with anyone, least of all my mother.

Wanderings

Ukraine, Magnitogorsk, Moscow 1930-1933

My mother refused to resign herself to the role of a guest in my paternal grandparents’ house, nor did she accept that her brothers should help her as if she were an invalid. She had turned twenty-four while her husband was trying to build an unpredictable future in far-off South America. She was determined to confront her ambiguous reality and overcome it. The likelihood of a family reunion had faded and could be postponed for years—or forever. Meanwhile, the implementation of the revolutionary process was creating job opportunities, but she was wasting them, constrained by her familial and emotional dependence.

“Even if it’s temporary, I must treat my waiting as if it’s permanent: I want and need to work,” she often reflected. Over time, this became an obsession.

My mother was willing to give up her plans if there was a chance to reunite with the father of her child. She wanted me to have a father, but due to her temperament and sense of dignity, she wasn’t prepared to wait indefinitely at her in-laws’ house for her husband to pay for the tickets or for the authorities to grant us an exit visa, which didn’t exist at that time.

Her decision to work would require significant effort and sacrifice. She was ready to face them, knowing she lacked work experience and that her chances of finding decent employment near Chón, a typical agricultural area, were virtually nonexistent. She needed to move to other regions to look for a job in industry. Steel and energy formed the backbone of the emerging socialist state. That’s where the key to the future lay, as the Party’s slogans continually emphasized.

My mother was ready to face, without fear, the reactions her decision would provoke: she had more than enough courage not to be bowed by difficulties.

The first problem: the immediate and inevitable opposition from her family. The second, a circumstantial consequence of the first: the care of her child.

If she tried on her own, she might be able to find work; with a child, it would be problematic, not to use the word “impossible,” which was excluded from her vocabulary.

The issue had to be solved in stages: if she found a job, her son could live with her when circumstances allowed. But during the attempt, who would take care of him?

When my mother hinted at her plans, my grandfather could barely conceal his irritability —he respected my mother and did not dare treat her with the same despotism he used with his children— but he didn’t hold back from making a few comments:

“Why do you need to work? Is there anything you lack in my house? As long as I’m alive, you’ll never have to worry. Neither you nor your son. I promise you.”

My grandfather was not willing to easily compromise. He found my mother’s decision not only inconceivable but also offensive to his dignity; he saw it as a ploy to cover up her true intentions.

My mother had to remember that she was a married woman, with an absent husband and a child she was obligated to care for. Out of respect for the family, it was essential that she live with them to avoid gossip.

To my grandfather, no change had occurred in the country’s mindset, so his bewilderment was genuine, despite the fact that he loved my mother as much as he loved his grandson.

From the day my father introduced Duñe (Dora) to them, my grandparents —each in their own way— loved her, charmed by her personality.

My mother was a graceful young woman, intelligent, with restrained manners, a soft-spoken nature, tolerant, respectful, and genuinely interested in others. She was also efficient in her household duties: an excellent cook, organized, energetic when facing problems, and skillful in solving them. Her presence infused the family dynamic with a newfound sense of calm and joy. By earning a privileged place in their affections, she was able to command respect and discreetly organize the daily chaos with finesse and care.

My mother was a liberating presence for my grandmother; she was able to relinquish the few tasks she handled at home and dedicate herself fully to her passion for books. My grandfather and my paternal uncles enjoyed a period of culinary well-being: they started eating at reasonable hours and no longer suffered the effects of my grandmother’s obsession with reading. It was a time of scarcity, but my mother cleverly compensated for the lack of resources; her creativity allowed my paternal family to discover, even during times of famine, the pleasure of good meals, which further deepened the affection and esteem they all felt for her.

However, it would be unfair to attribute my grandfather’s opposition merely to petty culinary desires or the fear that the efficient household structure would collapse. He loved us too much to accept the thought of us leaving. But there was nothing he could do: my mother’s stubborn determination eventually prevailed.

A few weeks later, she got a job at a factory near Dnieperpetrovsk, and I was left in the care of my grandparents, which is to say, no one, because they were not prepared to take care of me. It wasn’t long before they sent me to the house of their only daughter, Ite, who was married to Leizer, the practicing Jew I mentioned before. The couple lived not far from Chón, in a rural area. They had a son older than me, Dudek, who became my playmate.

After a long absence, my mother was finally able to visit me. I remember the scene of our first reunion. It was a winter night, and I was asleep. Somehow, by intuition, with no sound or reason, I opened my eyes. The room had a small window that was covered in a thin layer of ice from the outside. Through the window, I saw my mother’s smiling face, watching me. Instinctively, I jumped out of bed, ran to the door, and rushed outside to embrace her. Even though it was snowing, I barely felt the cold.

I was not yet four years old when my wandering began. I said goodbye to Chón, my grandparents, and uncles, and moved to Zapadenietz, to my maternal aunt and uncle’s home. A distance of twenty or thirty kilometers separated two very different worlds: my paternal side, full of tensions, and my maternal side, where peace and dialogue prevailed. I first lived in the home of my Aunt Brantse, who was married to a Communist Party member. The house was spacious, and my mother’s younger siblings often gathered or stayed there. In that home, I enjoyed the protection of family and a newfound sense of freedom. My unmarried uncles took care of me, talked to me, and treated me with affection, while my aunts, who were students at the time, showered me with tenderness, compensating for my mother’s absence. My mother visited when her duties allowed, but travel was not easy in those days; every trip required economic sacrifices and government authorizations to cross internal borders. Our reunions were marked by tears and promises. My mother always encouraged me with the hope that next time she would take me with her, but her vows were much like my father’s, as she couldn’t keep them. I was at the mercy of the family’s goodwill. When my oldest uncle got married, I lived with the new couple, then after some time returned to Aunt Brantse’s house, and later, I was sent back to Chón to stay with my grandparents, and eventually with my Aunt Ite and Uncle Leizer. I have known the confusion of exile from childhood.

I had become, despite the love they had for me, a burden. The country was enduring a deep crisis, and it took great strength to face the daily challenges. Another mouth to feed, another plate to serve, added to the difficulties, even if it was a child’s mouth. In my childhood, I witnessed —it may sound like a dreadful phrase, but it was a common sight— people wandering the streets with their bellies swollen from hunger, desperately begging for food and dying from malnutrition in the open air, in a country that proclaimed solidarity as its goal. As I’ve mentioned before, these were hard times.

I sensed certain veiled criticisms of my mother during some family conversations about her absence: they hurt me and, above all, humiliated me. I had become a burden.

Some nights I would fall into sadness and cry silently, hiding my tears. When I compared myself to other children, I felt abandoned and longed for my parents to come and rescue me. That was one of my favorite fantasies.

At last, the promises were fulfilled. While I was staying at my Aunt Ite’s house in Chón, my mother appeared unexpectedly, euphoric. She had gotten a job as an administrator in a metallurgical company in Magnitogorsk, an industrial city in the remote Ural Mountains. It was a unique opportunity that included the right to take me with her and several additional benefits: housing, a kindergarten for me, and, after a year or two, the possibility of relocating to Moscow. I was thrilled, but my grandparents opposed the plan.

“Why would you drag your son to the ends of the earth? What kind of life awaits him there? Who will take care of him if you’re working all day?” my grandfather argued. “Let him stay with us.”

My mother rejected all of his reasons. I remember her response, spoken with the firmness of a wronged heroine:

“I will never be separated from my son again. For no reason. Never again.”

Death among flowers

A stage of nomadic adventures began. We traveled by train—actually, by several trains—until we reached Magnitogorsk. First, we moved to Moscow in a rickety contraption that stopped at every station where hundreds of frustrated passengers had been waiting for days or weeks to get a seat. Sometimes, when switching trains, we had to spend the night at some station, lying down on our bundles to prevent them from being stolen. After ten days of travel, we arrived in Magnitogorsk.

The Magnitogorsk project implemented the ideological tenets of Stalinism, which emphasized the industrialization of the country as a goal following the failure of the agrarian reform.

A forest of chimneys and a polluted atmosphere filled the residents of that city with pride. It was considered the heroine of an epic whose goal was to match and surpass the economic level of capitalist states.

We were assigned a prefabricated house that we shared with several families in a makeshift residential area bordering the industrial zone. The housing complex had two communal bathrooms: one for women, and one for men. The smoke and noise never stopped. Today, Magnitogorsk is one of the most polluted cities on the planet, because the word ecology wasn’t part of the revolutionary vocabulary. The new man, by ideological determination, was supposed to enjoy excellent health amid the clamor of machines and creative chemistry. No one had to worry about environmental pollution, a phenomenon ignored by Stakhanovist socialism.

Magnitogorsk turned into the Far West of the Soviet Far East, a mirage where adventurers, dreamers, and idealists from all corners, both Asian and European, converged. This ambitious project deified statistics, idolized production, promoted technology at any cost, and prematurely canonized the creator of these miracles. I hadn’t yet turned five when I began to recite orchestrated praises in kindergarten to the genius of steel, the leader of the people, Comrade Joseph Stalin.

My mother worked all day, and I attended kindergarten until dusk. Later, with other neighborhood children, we played and engaged in “scientific research” by spying on the women’s bathrooms as they enjoyed their showers.