Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jonathan Ball

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

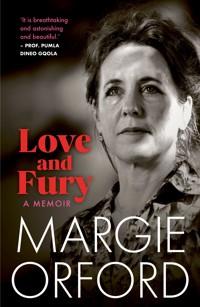

Love and Fury traces a woman's fierce love and righteous rage, unravelling entanglements that are at once tender and traumatic. Renowned South African crime writer Margie Orford offers candid revelations, both political and personal, which have shaped her life and influenced her writing. Surviving marriage, divorce, depression, personal loss and sexual assault, Orford recounts memories of what she has experienced as a woman, a wife, a mother – and particularly as a writer. Love and Fury demonstrates the enduring, debilitating effects of hurt and harm, but at the same time it exemplifies the power of love, self-belief and self-reflection, ultimately offering a message of hope. This book is for every person who has experienced passion and wrath – and who looks beyond this to the light. 'This book kept me alive.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 465

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Jonathan Ball Publishers

JOHANNESBURG & CAPE TOWN

For my daughters

To Unravel a Torment You Must Begin Somewhere

– Louise Bourgeois

CONTENTS

LONDON

one

The flat at the top of a Dickensian house I moved into in the autumn of 2018 had two poky bedrooms – one for me; a rotation of daughters would share the other – but the living room had a panoramic view of Hampstead Heath, the only wild place left in London. Other writers had stayed there before me, my elderly landlords told me when I went to lunch with them. Famous writers wrote famous books at the very table they had decked with a bowl of olives, a salad and a basket of stale bread.

‘You’ll be happy here,’ they said, gesturing towards the serene Heath where the leaves were turning russet and gold.

I agreed. I looked forward to settling. To making their home mine. To finishing a book at their table. It was arranged. Money was exchanged for keys to the eighth place I had lived in during the three vagrant years since I packed the clothes I could fit into a large red suitcase and fled Cape Town in 2015.

The next day I dragged that case up four flights of narrow stairs and put it next to my books and bin bags stuffed with bedding. I set about scouring a decade of other people’s grime from carpets, windows and walls. I washed the mismatched crockery, cutlery, pots and pans crammed into the kitchen cupboards. I scrubbed floors, stripped walls of the landlords’ looming pictures, packed away their ornaments and winnowed the furniture down to the bare minimum.

I rearranged plants, books, cushions, furniture. I hung the three small oils I had brought from South Africa – a landscape with aloes in vivid red bloom, a portrait of my Granny Margaret as a cherubic baby and one of me as a fat-cheeked toddler in blue dungarees. Those paintings had hung in all twelve houses I had lived in as a child, and they made yet another place that wasn’t mine home.

I threw out the old bills and takeaway menus jamming the drawer in the dining table to make space for the papers one needs to prove to the authorities that one is who one says one is – my passports, my daughters’ too, our birth certificates, my divorce papers, tax records.

A photograph fell out. London, 1988, scrawled on the back. I picked it up and turned it over and there we were, me and my ex-husband, my children’s father, in a photo booth. I am wearing a neon-pink scarf and black-and-silver starburst earrings that always got tangled in my hair, I’m looking straight at the camera, and at myself thirty years later transfixed by the remembered sensation of Aidan nuzzling my ear. His eyes, laughter in them, are also turned towards the camera. Seeing us looking at me gave me vertigo.

It had been taken the year before we married. I was twenty-four then, too young to know a wedding is as much a beginning as it is an ending. That marriage is the institution in which, generation after generation, women are forged. That it is both sanctuary and prison. That success can look like failure and failure like success. That marriage can be a place where loneliness hides in plain sight. I shoved that picture containing our optimism and naivety to the back of the drawer.

That first night in my new bed with its freshly laundered sheets, I could not sleep. When the blackbirds called the dawn, I got up, made coffee, and looked out at the Heath. The clouds were pink and the sky orange above a slender spire surrounded by tall trees. My first wedding in the hot June of 1989 took place under one of those trees, on one of those lawns. Had that been my first step in the direction leading to where I was now, looking for a way to disappear?

For months, I’d been trying to write a suicide note, but my ‘writing’, which I regard as separate from me – something life- and death-giving, beneficent and tyrannical as the Furies, those ancient goddesses of life, death and vengeance – vetoed me.

Now I see their tactics, the Furies’ and the writing’s. But then I could not, so it bewildered me when I sat down to draft my farewell note – calm because I was doing something – that questions of form would swirl. What would it say? What reasons does one give? What reasons does one need to put a stop to things, this thing that is oneself, one’s self, my self? I wished to set her/me free – to turn to air. To escape. But I could not find the right words. Writing was the one thing I knew how to do, but when I needed it most it abandoned me. It made me desperate. And mad.

‘Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again … ’ Virginia Woolf wrote in the suicide note addressed to her husband. I did not hear voices like she did; I heard muffled silence; felt my lack of ballast.

I tried copying hers, but I had no ‘dearest’ to address. Must one stay alive simply because there is no one to write to? There was a void, and I was falling, but try as I might, try as I did, over and over, I could not write my own note and it seemed unethical to plagiarise someone else’s death.

So, I cast about for a way to leave life in a manner that would not disturb anyone, as a mother tiptoes away from a sleeping baby. But babies wake and cry for the mother’s return. I knew because I have had three, all grown and nest-flown now, but still my babies.

I considered giving my life away. Donating it as if it were a spare organ – a kidney, say. But what (here the doubt crept in) would I be donating? This worried me. Would the recipient be able to make something of the extra time (my time) or would they become as mad as I have been?

To know, I would have to better understand this tenacious life of mine. I would have to go out into the world again and look for what I had not been able to see before. It was a raw November day and in the grip of this lucid insanity, I put on my coat and gloves, spiralled down the stairs and stepped into the street.

A hundred paces ahead was a path onto the Heath. I took it, and plunged into the trees, searching for the place where we had eaten our optimistic wedding feast. Looking for the grassy slope where we’d sipped champagne under a gnarled oak. But the trees had grown or died back, and I could not find the place. I could not find myself either.

The rain started, scudding over the muddy ground, driving me away. Once inside, I retrieved my pen and notebooks, tearing out pages of ‘To whom it may concern’ death notes.

I have had to be quiet and patient long enough for the shy night creatures of the mind to slip out of their shadows so I could befriend them.

This book kept me alive; I will give it that.

two

‘How can you two not have met?’ asked Karen, introducing me to Aidan in the noisy university cafeteria five minutes before our first lecture. ‘You know all the same people.’ She dashed off to class, but I lingered. Aidan tore his doughnut in two, and his copper bangles jangled as he held half out to me. When I took it, his warm, sugary fingers touched mine and I could imagine wanting more.

‘Do you want to see Battleship Potemkin?’ I asked. ‘I’m doing English and Film Honours, so we’re watching Hitchcock and all these old silent Russian movies.’

‘I do,’ said Aidan. He walked down University Avenue with me while I explained my theories about the male gaze, acquired from that week’s reading list.

‘I love film,’ he said. How I wanted his eyes on me.

That was 1987 and Aidan was studying architecture, which was how we worked out he knew my sister – her boyfriend was doing the same degree. Aidan met Melle when she stopped her car on the highway below the university at rush hour, blocking the traffic in both directions because a golden mole was trying to cross. Aidan ensured that Melle was not run over as she shepherded the panicked animal across four lanes of traffic. I could picture her – fearless, protective, her blonde hair whipping about in the southeaster.

‘That’s my sister for you,’ I whispered as I smuggled him into the darkened projection room. The film had already started so we broke off, but there was electricity where our forearms, laid casually on the armrests, touched.

The first night we spent together we had gone to a fancy dress party – me as Cyndi Lauper’s ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’, him as Godzilla. The morning after, we went to Camps Bay as the sun rose, and it was decided, in that wordless way of the Eighties, that we were together.

I loved having someone to meet after lectures, go to the beach with, make breakfast for on Sundays. The routine of romance steadied me and gave me a sense of belonging. A year later, after we graduated – him an architect; me whatever it is people with English Literature degrees are – he was called up. He had done his two years of conscripted military service on the Namibian border, but all white men were being summoned to do what were euphemistically called ‘camps’. The South African army had invaded the black townships that ringed South African cities. There, from their armoured vehicles, they shot to kill, intent on crushing the insurrection against the apartheid state. There was no political fence to sit on. To avoid the army, Aidan, like many of the men of his generation, left the country.

He wrote to me from London, his elegant handwriting filling aerogrammes with his longing for me, for the softness of my skin and my funny stories, describing a Grace Jones concert, the friends he’d seen there. He filled the margins with witty sketches, all rendered with a few sure strokes of black ink – cavorting dogs, a tiny drawing of St Paul’s, children in a park. Those miniatures, his glimpses, made me long for him and for the tranquillity of the London he captured in his drawings. Our correspondence was more intimate and eloquent than any conversations we’d had. I found it easier to love people when I was not with them – something I’d learned from boarding school.

His invitation to join him was the promise of a life elsewhere. South Africa’s hold on me was strong, but it was impossible in 1988 to imagine an end to its undeclared civil war. The leaden heaviness lifted when I resigned from my job as a salesgirl in a dress shop, giving away everything except the clothes I could fit into a single suitcase, and fled to London where, in the accidental city of my birth, together with a tall, sheltering man, I was sure to belong.

Aidan was waiting for me at the station in Kensal Rise in west London on the wet evening of my arrival in November 1988. Our kiss was awkward. It had been three months and I had forgotten how tall he was, but he took my bag and I fell into step beside him. Our conversation went in fits and starts as if we were improvising our lines. He told me about his job at an architectural firm, that he’d made plans to meet up with some people I knew at the pub on Friday after work. I said a pub sounded nice. I told him his family was well when Melle and I visited them on their apple farm outside Cape Town. We’d driven along the N2. There were bulldozers crushing the zinc shacks along the highway. I saw a little boy with a red toy truck clutched to his chest running across a stretch of sand between pyres of black smoke rising from a razed settlement. We closed the windows, but still we choked on the stench of burning rubber, I told him as we turned into Bathurst Gardens.

The house where Aidan rented a room was halfway down the street. It had stained glass in the front door, which cast lozenges of yellow light on the path. There was a phone in the hallway, a book next to it for recording calls so that the monthly bill could be tallied and shared. The people we would be sharing with were in the kitchen. ‘Hey,’ said one, an American, pointing to Aidan, ‘that dude has been looking forward to having you here!’ The other two, English, offered tea. ‘Maybe a bit later,’ I smiled, and followed Aidan up the narrow stairs.

He opened the door into his bedroom, now ours. It was the front room on the first floor, and it had a bay window. In the middle of it was the bed. A huge futon on the floor, with duvet and pillows covered in bachelor-pad black. At the foot was a small television set. I walked over to the window, opened the curtains, and looked down the desolate ribbon of street lined with identical houses. Aidan came and put his arms around me, and we went to bed to find a way back to each other.

That Christmas, the trees were skeletons against the ashen sky, while the snow shone on Hampstead Heath. We threw snowballs, laughing because we could not feel our fingers. New Year 1989 the water froze, but we bundled up and walked along the canals from Kensal Rise to Camden Town where, among the cheap punk T-shirts, tartan miniskirts and fishnets, we ducked into a photobooth and took pictures of us clowning. I snipped up the set of four photographs, posting one to my parents, one to Aidan’s, and one to my sister. Those photo-booth pictures were a rite of relationship passage, a tacit announcement we were no longer two but one. Aidan-and-Margie to his friends and relations; Margie-and-Aidan to mine.

Among the reasons Aidan had fallen for me were the stories I told, especially my travel tales from 1986: hitchhiking from Lake Van in the far east of Turkey to Amsterdam, where I crashed my bicycle in front of a gay S&M club and had Mercurochrome dabbed on my wounds by musclemen in leather shorts and gimp masks; having my palm read in Marrakesh. He wanted to travel with me, and we’d had every intention to do so, but we were marooned.

Somehow, together, we had fallen into an inertia of coupledom. Our far-flung plans vanished into pubs on Fridays, art galleries on Saturdays, and Sunday lunches in large homes in the leafy parts of London with friends of our parents. It was as if the M25, the city’s ring road, was a cordon we could not escape.

three

In January 1989 my savings ran out, so I registered with an employment agency. The man who took my details told me South Africans were popular. We were hard-working and self-reliant, he said. Not nannied by the state, like in Britain. I did not disagree with him. He whipped through the records and references I had given him. He was glad to see I had a first-class degree. He would send off my CV and samples of my writing to advertisers, publishers and magazines.

Sure enough, there was interest. An advertising agency or a publisher or a magazine – exactly which, I am no longer sure – shortlisted me for a position so junior there was nothing beneath it. The interview would be at the grand building on the Thames where the company had its offices.

I was ushered into the boardroom where two women in suits sat at an oval table. They had their backs to the window, so I could not read their faces, and they had my CV in front of them.

‘You have a good turn of phrase,’ one said, pointing a manicured finger at photocopies of my student articles. They asked me questions about the research I had done, the interviews, the writing. It was like an exam, and I thrived, drilled from childhood to debate my father, to hold my own, to listen and to respond to the facts. They seemed impressed. I was pleased. The one on the left made notes in the folder with my name on it. The one on the right leaned forward and said she’d been to Oxford and read the Romantics. ‘What do you think of them?’ she asked.

‘I love “Daffodils” and “Westminster Bridge”, but the “caverns measureless to man” is my favourite,’ I said. ‘I was studying Coleridge when I was arrested.’

‘Arrested?’ The notetaker riffled through my transcripts, as if looking for something she had missed. ‘What for?’

Fool that I was, I rushed on, not for a moment thinking she might think I was a criminal. ‘Protesting against the State of Emergency. You see, the police had the power to arrest anyone, to detain without trial. By that time thousands of people were in detention; I was nothing special.’

The interview woman put her pen down. I saw the ice in her eyes, but it was too late for me to stop.

‘I was studying for my final exams when a friend came by and told me to come to campus with her. There’s no arguing with Miriam, so I went. When we got there, we joined the others and faced off the riot police across the road. I remember the loudhailer: “You’ve got five minutes to disperse!” But we didn’t move, cops surged towards us, and we ran. I turned and saw four coming at me, one pulling ahead of the others, and then I passed out. When I came round a cop was telling me to get up. But my legs didn’t work, so he pulled me up and walked me as if I were his drunk girlfriend. Other students were being loaded into a van, but he put me into a car. I remember a policeman drumming his fingers on the steering wheel. They took me to the police station, and from there we were all taken to Pollsmoor.’

They both looked blank.

‘That’s the maximum-security prison where Mandela was taken after Robben Island.’

The two women exchanged glances. ‘And what was it like in there?’

‘A nightmare,’ I said. ‘The police shouted at us to get out. There were floodlights, six-metre walls with razor wire, guards with Alsatians straining at their leads. The prison services didn’t know what to do with a bunch of white girls, but they soon figured this out. We were in solitary for a few days, and then all of us, twenty-one or more, were in a cell for eight people.’

‘That’s where you wrote your finals?’ said the one with my transcripts.

‘I did,’ I said. ‘There was such a fuss about us white students getting arrested that the Minister of the Interior granted us permission to write exams. Only three of us gave it a go, but at least we were given our books. The Romantics – the daffodils, and Blake’s rose with the worm.’

The Oxford woman didn’t smile.

‘So, you don’t have a criminal record?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘They charged us with crazy things, but the judge dismissed these.’

The way they looked at me, they would never call me back, I knew that, but we said goodbye as if they might.

Out on the street, fighting its tide of rushing people, buffeted by passers-by, I burned with shame. Thousands were in detention and the police were shooting people in the townships every day. There was no heroism in an accidental arrest. I had made a story of it, but had been unable to convey to the two women, shoulder pads as crisp as if they were soldiers in a firing squad, the terror I’d felt as the door of the cell slammed shut. The sound a bullet in my back. My cell was two paces long, its width that of my outstretched arms. My trousers sagged, the belt taken so I would not be able to hang myself.

This was not something I had considered before, but the thought of suicide, now that it was there, was alluring – a silver flash, a fish diving for freedom in dark water.

Feeling insubstantial, I turned down another busy road. I understood that the law, and what is right, are two separate things. I had been shaped by a place where they were in opposition to each other. Unlike those two women, I thought. By then I did not know where I was and I was desperate to get home, but when I tried to read the street signs the letters jumbled, and I could not decipher the names of any of the streets. I pulled my coat closer as I hurried down another street I did not recognise.

My cell had been colder than this, and empty apart from a bulb behind a metal grille, a toilet without a lid, and a bed with a folded grey blanket on it. I had wrapped the blanket around my shoulders. It released the smell of the woman who had been there before me. I lay on her bed and closed my eyes, but it had been impossible to sleep.

A bag arrived with my name on it in Miriam’s handwriting. I hugged it close as if it were my friend herself. Inside was a pair of new sheepskin slippers, a size too big but so soft, and a froth of white lace. A party dress for a party girl. I put it on and, Madonna’s ‘Like a Virgin’ playing in my head, pirouetted. There was also soap, face cream, shampoo, tampons and lipstick. I didn’t have a mirror in my cell, but I applied the red lipstick, and, for a moment, felt defiant. I dropped to the floor and tried to do push-ups the way real political prisoners did, but my arms, not seeing the sense of what I was making them do, refused to lift me.

I made a jaunty tale of those failed exercises and of the whack-whack-whack of our guard-invigilator’s rifle butt on the desks when we wrote exams. That was at the party friends had organised to celebrate my release – beers, hugs, cigarettes, compliments on how great I looked, on how thin I was. ‘I couldn’t eat,’ I said with a laugh. ‘I threw everything up.’

‘It makes a good story, doesn’t it, Margs?’ said a friend, the expression in his eyes speculative – or bored. That shut me up. I did not know how else to make sense of what had happened, except by fashioning my terror and fury into a tale. Fortunately, there was dancing and I could escape with the The Clash thrashing out ‘London’s Calling’.

Everything was over as if it had never happened. Except it had not been a jaunt and it wasn’t over. The girl who went through those prison gates was different to the woman who came out, and I did not always recognise her.

The doctor who checked my pulse and blood pressure said I was in perfect physical nick, but was I coping mentally? He was the only person who asked that question. I wanted to fling myself into his arms and tell him how I struggled with time, with making it pass. Tell him it was as if I was caught in invisible quicksand. That ever since those two security policemen had interrogated me, one standing so close that I could feel his hot breath on my neck, I’d had nightmares in which men, grim-faced and skeletal as Giacometti sculptures, chased me – so I did not, could not, sleep, and I was so tired I thought I would go insane. I opened my mouth to say this, but all that came out was, ‘I’m fine.’

I could not speak to this worried-looking man. His niece had been in solitary confinement for months. We prisoners had talked to her when filing past her window on our way to the exercise yard, but the wardens told us that was forbidden. The next day we sang to her, our voices soaring above the concrete walls. When we went past the next day, workmen were welding a metal sheet over her window. Because of our singing, she was immured in darkness. So what could I possibly have to complain about mentally?

Afterwards, whenever our digs were empty, I’d lie on my bed and stare at the ceiling. When my last exam came round I intended to get up, get to work, but instead I watched motes of dust glide up and down the afternoon rays that shone through a slit in the curtains. Which I was doing when a motorbike pulled up outside. I opened the front door, and a friend was standing there with a helmet in his hands. He held it out to me and said, ‘I’ve come to take you for a ride.’

The houses of Cape Town soon vanished as we rode through fynbos and blooming proteas. At Cape Point the waves pitched at the jagged black rocks where the continent knifed into the southern Atlantic. My eyes narrowed against the tormenting wind, and as we sat looking, we passed each other the half-jack of whiskey he had brought with him.

It was dark when we left, the moon a gleaming crescent bobbing in the churning sea beside us. I felt better. All I needed to make time pass was to keep moving because then I felt alive. A week later, I left South Africa, and for a year I did not stop moving. I did not mean to return, but by the end of 1986 I was adrift in a sea of homesickness – the name I then gave to the despair I felt – and so I returned, met Aidan in 1987, and followed him to London.

All this circularity, this restless movement without purpose, had resulted in me interviewing for a job I wanted but could not really imagine doing. Lobbing that hand grenade of a tale across that boardroom table foreclosed a particular kind of future for myself. I had ensured that whatever it was I was doing in London would be temporary.

That cold, frantic girl turning down wrong London street after wrong London street in 1989 did not know why she seemed unable to settle in England. It is only now, after moving myself half to death, that I understand I did not know how to feel at home in a what seemed like a safe place with a predictable future. Nothing felt familiar. Nothing felt like home. I could not attach. The safety felt dangerous. The predictability made me want to die.

four

February 1989 brought astonishing drifts of snowdrops. In March the daffodils gleamed yellow in the exposed earth skirting the path where Aidan and I were walking. We had visited an English friend and her baby earlier. I felt at home in the busy, friendly mayhem of my friend’s house – her mother, brothers and sisters coming and going. I loved the tumult and how a baby made the family and the house busy and purposeful. When I held the little girl in my arms, my loneliness receded and my heart stilled, but for all the words I was capable of marshalling about any topic flung at me, I could not acknowledge, let alone articulate, the yearning I felt for a baby of my own.

There was no feminist language then, or none that I knew of, which accommodated the desire for maternity. I had been so determined not to be dragged down among the women, where I would lose myself in the invisible labour of cooking, cleaning, caring, that attending to my desire for a child was like looking at one of the Gorgons. It turned me to stone, so I looked away and pretended it wasn’t there.

There is no way to say something out loud that you can’t say to yourself first. And so I was silent. But the body knows what the mind doesn’t, and it has its own ways of getting what it wants, and I had gone off the pill. I told Aidan it made me nauseous and that my breasts hurt, which was the truth. I said hormones made me blue and that was true too. I was blue. The tears I had not shed in South Africa had risen to the surface since I had been in London. They would appear when I rattled along on the Underground to work. Come when I drifted through the crowds in St James’s Park, an invisible foreigner in the strange and ordered country where I had been born but which was as unfamiliar to me as the moon.

Up ahead was the entrance to London Zoo. Flocks of children, women with prams and men with them because it was Sunday were buying tickets and King Cones. On a whim we bought tickets and ice creams and went in. Arm in arm, we walked past the reptile house, the zebras and their soggy faux savannah, the cage where the big baboons glowered at a group of boys who leapt about grunting. People clustered around the chilly elephants, but on we went towards the rhinoceros racing up and down her enclosure. Spectators leaned over the metal paling protecting her from them, teenage boys shouting how ugly she was, how big, how clumsy, such a dinosaur, such a fat slag. I leaned against the paling too, but I said nothing, as if my silence would set me apart from those others.

Thud-thud-thud she went; not so much a sound as a tremor in the earth. My heart thudded in unison with the rhino as she charged down the narrow concrete culvert, oblivious to the taunts and catcalls from the watching crowd. Oblivious to the Coke can bouncing off her rump.

Her flanks were bleeding – her hipbones and shoulders rubbed raw where she knocked the concrete barrier as she ran. Fifty paces north, turn, the same fifty paces south: the length and breadth of her shrunken world. When she turned, I locked eyes with her, but she did not see me, she did not see anyone. Her small fierce eyes were fixed, her gaze turned towards the immense distance within herself where she retreated because there was no escape. The crowd found it hilarious. They laughed at how she ran, their lumbering prisoner, and curled their cruel pink tongues around their ice creams.

Sorrow for this tortured animal filled my throat, but I could not turn away from the sight of her suffering. Aidan folded me against his chest and his heartbeat drowned out the din of the world. He led me out of the zoo. We walked back along Regent’s Canal, and the sunlight danced on the dirty water where a pair of swans made elegant turns.

five

Don’t throw up on him, I commanded myself. The morning tube into Central London was packed. The man wedged in next to me smelled of aftershave, toothpaste, fried eggs and deodorant sprayed onto unwashed armpits. It turned my stomach. I gripped The Satanic Verses, wrapped in a brown paper bag because of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, my knuckles white. If the sweaty man next to me did not move soon, I would need the bag. The train stopped. The doors opened, the man left and I could breathe.

Another man approached. ‘I’ll be sick on you if you sit here,’ I hissed. He backed away from me, as people do from the mad. Thank god, because that pocket of air got me to the next stop.

I eddied along the stream of people flowing up into the fresh April air. The nausea receded as I walked across Trafalgar Square, past the anti-apartheid protestors encamped outside South Africa House since 1986, the bronze lions, Nelson on his column, before turning into Spring Gardens. I pushed open the heavy brass doors of the British Council and took the lift to the top floor, where I was temping in the Press Office. I picked up a pile of newspapers from the mailroom. They rustled when I opened them, with their traces of faraway.

Those newspapers made me yearn for the thrill of living by my wits in foreign tongues. For the freedom I had felt when I slipped the traces of South Africa for the first time. When it got cold in Northern Europe, I had gone south and fallen for a blond Italian in Lisbon. We’d gone to Morocco together. He’d said, ‘Come to Merano with me’, but I lost my travelling nerve at the Algerian border and returned to South Africa. We wrote to each other for a while but that had petered out. Reaching for my razor-sharp scissors with my right hand, I felt a pang for that abandoned future.

Mine was the most junior of junior positions, but I loved it. I was a human search engine. My task was to read all English-language newspapers, from the Far East to the West. I started with the Hong Kong papers, then the rest of Asia, Australia, New Zealand. After Pakistan and India came the Soviet Union and the Middle East. When Africa was done, I turned to Europe. After that I skipped to the Americas, parsing those papers, only a day or two out of date, for the British Council’s small glories and its efforts at winning hearts and minds in former colonies and other places where influence mattered. I clipped out stories that mentioned the British Council in a world changing as the Cold War thawed. I snipped out the stories mentioning English books, art, films and television.

Why aren’t you doing this? a voice in my head whispered as I read the journalists’ bylines. Why are you cutting out other people’s stories?Why aren’t you writing?

I’d written before. At sixteen, I wrote to Fairlady magazine, prompted by a scene in An Officer and a Gentleman, a film where white World War II soldiers who tried to stop a black officer from dancing with a white woman were roughed up and thrown out. When the couple resumed their turn on the dance floor, the Cape Town audience clapped. It gave me hope to see those on-screen racists sent packing. So, I wrote and was published on the Letters page. I felt a swell of joy when I saw my words in print.

At university, I wrote for the student newspaper. By the time I was in second year, every article was vetted by lawyers to get it past the ever-present censors, which showed me the power of words to unsettle tyranny.

Small commissions came my way after I graduated, and while they all engaged my intellect, none captured my heart. These were the pieces in the portfolio that the navy-blue women in the fancy office had looked at and liked. It had not included my short fiction and poetry. That was work I showed no one because it frightened me.

I tried, without yet having read Angela Carter, Kathy Acker or Tsitsi Dangarembga, who would one day show me how, to capture the turbulence of the body. I tried to write its desires, excesses and subjugations, but I could not think of this intimate woman’s writing as political. I had written love stories that acknowledged cruelty and fear. I had put the body at the centre of a tale and tried to express the passions that had gripped me. But I had failed. The savage censor in me tore up my pages, revolted by the self that appeared on the page – naked, wild, vulnerable.

Writing, like sex, carries with it disruption, furtiveness, shame and power, but I vowed not to write until I could write about things other than myself. But what else did I know? So, instead of finding out, I stopped, losing my writing nerve before I began. I felt that self-inflicted loss as an impotence, but instead I had cut something off. It was a castration. There is no word for female impotence or castration. Women are, if one goes along with Freud, a wound, but I was not sure I agreed. Writing and sex, creativity and love should be entwined, but I did not yet know how to weave them together. It felt then as if it had to be one at the expense of the other: writing or sex, creativity or love.

I put my scissors down and took my pile of clippings over to my pink-shirted boss. He thanked me without looking up and so, my work done, I returned to my desk and looked out of the seventh-floor window, waiting out the end of the working day. Looking out over the slate roofs I saw a flock of pigeons swirl in the wind. The unpredictable movement made me think of the man I had fallen in love with at nineteen.

He had blown me off course when he caught my eye at a nightclub. He sat opposite me, and I lit a cigarette. He had taken the box of matches from me, struck a match, and put it back into the box. It burst into flame, but he grabbed my hands to stop me from putting out the conflagration. I never wanted to let him go, so I took him home and put myself in his hands. When he slept, I caressed his shoulder, mesmerised by the tattoo of a scorpion, its tensile tail poised in readiness to strike.

He stayed for a year. It was thrilling, but I was off-kilter with a falling that never seemed to stop. I could not think, not with that tumult of feeling, and I could not work properly. Mind or body – that was the choice because I did not know how to inhabit the middle ground. I chose the body, a wild leap that made me afraid, as did the intensity of my desire to lose myself, to give myself over to him. He liked the ‘click’ that his new flick-knife made. He persuaded me to stand with my back to our bedroom door. He took the measure of me through dark, narrowed eyes.

‘Don’t move,’ he said. The blade whizzed past the top of my head. He took it out of the wood. It flew past my arms, my waist and my hips. A deft, daft game, but I trusted him. I had no fear, standing there with my arms spread out against the door. He never harmed me, but still, I cannot explain why I stood there; why I believed that the knife would not pierce me; why I did not care if it did. I relinquished myself because he asked me to. I would have done anything for him, which is why I broke it off in the end.

I was not able to tolerate being that trusting, so I ended things. It was love that undid me. Love stole a woman from herself. I could not bear how love unravelled logic, undid controls, made me abject. He slipped past my defences, disarmed me, made me stand before him, undefended. When I lost the studded leather belt he made for me, as narrow as an asp around my waist, I cried, though by then I was with someone safer, less savagely transformative, whom I could live alongside intact, separate, myself.

The five o’clock flurry signalled the end of that working day. Everybody downed pens, picked up bags, put on coats, jammed into lifts, and scattered across Trafalgar Square. By then my nausea had returned. Despite having had sex for weeks without contraception, I had not thought about conception, but the evidence was stacking up; so I went into the chemist at the entrance to the Underground, asked for a pregnancy test, and blushed as I paid. I shoved it into my coat pocket as I took the escalator down to the crowded platform. More people arrived, jostling me along until there was nowhere further to go.

‘Train’s late,’ a voice announced over the public address system. ‘Body on tracks.’

Around me, tongues clicked in annoyance at the inconvenience. An accident or a suicide, no one knew. We shifted and muttered on the platform, trying to work out how to make our onward journeys to circumnavigate this inconvenient corpse.

six

It was after eight when I reached the pub where I was meeting Aidan and some friends. ‘Sorry I’m late,’ I said. ‘Body on tracks.’ Everyone laughed at my imitation of the cold, calm voice. I slipped in next to Aidan and he placed a warm hand at the base of my back. Somebody poured me a glass of white wine, but I did not drink it.

It was past eleven when we paid our portion of the bill and we left. I said nothing about the test in my coat pocket as we walked home, but that did not stop me from feeling that I was about to float away.

Night was tilting towards the dawn when I eased myself out of the bed so as not to wake Aidan. I felt my way to the grubby communal bathroom. Half asleep, bladder full, I unwrapped the pregnancy test and read the instructions: Urinate on stick. Wait.

I urinated. I waited. And, as if by magic, a line materialised on the plastic strip. One blue line appeared, then another. I was pregnant. My unquiet heart was no longer alone. I turned my mind’s ear inwards, listening. The numbness inside me fled. I had a companion – a tiny accumulation of cells doubling and folding into a new person. My body was a sanctuary, providing protection and shelter. I ran my hands over my breasts, my still-narrow waist, my rounded hips, grateful to the potent body that had thrown me a lifeline.

What about your life, asked my mind’s chilly voice, your career, your writing?

I will do all of that later, my exultant body replied, I can do anything. I will do everything. I will come back to you.

Never in my life had I felt such certainty. The drift was gone. The doubt was gone. The future was now. I knew what it would be. I was so certain. I would have this baby. This comrade-in-arms. I would not be like all the women who had gone before me. Women whose lives had been subsumed by men and children and their demands. Lives deferred and lost. I was a free woman. I would find a new way. I did not have to be dependent. I could choose what to do. I could choose who to be. I could circumvent the tyranny of biology. I felt as if I had robbed a bank and got away with it. I was elated. My body knew what it wanted, so it had rebelled and taken charge.

I made tea and took two mugs upstairs, setting Aidan’s down with a sharp little click on his bedside table. He did not wake, so I opened the curtains and flooded our bedroom with spring sunshine. I waited until he had taken a sip of tea before I told him. I told him how certain I was about this baby. Certain in a way I had never been before. He looked at me with an expression of bewildered tenderness and asked what I thought we should do.

‘Have the baby,’ I said. ‘There’s no point talking about it. We could talk about it, but I can’t make a different decision.’

I was going to have the baby. I had to. The certainty was in my body. In my cells. I could not argue with it. It was decided in a way that I, who usually thought so much, found strange. He was free to choose to be part of this or not, I told him. I could not bear the idea of coercing someone. I could only value love – only believe it was love – if it was freely given, without obligation.

He opened his arms to me. I went over and got into bed with him and it was such a relief to stop talking, to stop standing to attention, and to lie against his chest listening to his familiar heartbeat.

When Aidan got home at the end of that strange and secret day when it was only the two of us who knew we had made a new person, he told me he had ridden his bike straight into the back of a stationary truck on his way to work that morning. I laughed at the harmless accident. Laughter confirmed what had been decided that morning when he said he would be part of it all. I knew then, for all my bravado, that I would not have to do this alone, and I was happy.

I dreamed of my baby, and in the dream, one whose vividness has never faded, she appeared beside the bed I shared with Aidan. Until then, I had not thought of the embryo as separate from me, but there she was, beside my bed, gazing at me. When, in my dream, I opened my eyes and saw her face, the beautiful face – high, wide cheekbones and slanting eyes – that she has to this day, I smiled. ‘Don’t worry,’ she said, ‘I’m a girl and we’ll do this together.’ My fear of not being up to the task dissipated. Her dream words gave me confidence in our capacity to be mother and daughter.

seven

After I had been to the clinic, had proper tests done and told the kind-faced nurse I knew what my choices were and having this baby was decided, I phoned my parents in Windhoek, Namibia. ‘Dr Orford’s home.’ My mother’s doctor’s-wife voice always startled me.

‘Mum,’ I said. ‘It’s me.’

‘Darling! How lovely to hear you.’ She switched to her mother-voice and shouted to my father, ‘It’s Margie! She’s on the phone.’

I was so nervous I didn’t say hello when he joined her on the line. ‘I think you should sit down,’ I said. ‘I’ve got something to tell you.’

‘You’re pregnant,’ said my mother.

‘How did you know?’ I asked, the wind taken out of my sails.

‘You’ve done everything else.’ My father laughed ruefully. I laughed with him, even though twenty-four was far too young to have ‘done everything’. I didn’t know what to say after that, but my mother must have said something because the conversation fitted-and-started back to life. When it found its way back onto a medical track, things steadied. My father would phone his old gynae professor at St Mary’s Hospital in London. He took care of the Queen. Now he would take care of me.

My parents had never met Aidan. I had not taken him, or any other boyfriend, to Windhoek, but Melle would vouch for him; he’d helped her save that mole. I handed the phone to Aidan, and the three of them spoke. When that was over, he was going to phone his parents, but I was exhausted by the relentless morning sickness so I went to lie down.

I closed my eyes, turning my gaze inwards so I could see the little alien who now inhabited me. I clasped my hands over my flat belly. The small creature whose life depended on mine needed all my love, time and attention. She made sense of things. We were a team.

Aidan came in. ‘My mother says if men aren’t married to the mothers, they can lose touch with their children.’ He sat next to me on the bed. ‘She says I should ask you to marry me.’

I liked Aidan’s mother. My own mother said the reason she agreed to marry my father was because of his wonderful mother, Margaret. I adored my grandmother. She and my grandfather’s ordered marriage and their farm, Bosworth, the place I thought of as home even though I only visited there, was a world entire of itself.

The gentle way Aidan stroked my face reassured me. What he was offering me seemed to be a sanctuary. I held out my hand to him, and stepped into it.

Our wedding, to be held in June in a registry office, was hastily arranged. It did not enter my head to have a bridesmaid. I did not think to invite my sister and brother. My friends – lawyers and journalists – were in South Africa, busy with the struggle against apartheid. It seemed frivolous to invite them. So far to fly. So expensive. But Aidan’s parents and my mother would come over. My father could not make it. His surgery list was already set; it was impossible to cancel those operations.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I assured him, although my throat was tight with tears. ‘Ours isn’t going to be the kind of wedding where there’ll be walking down aisles. I’m keeping my name. I’m a feminist, Dad, I don’t believe in one man giving me to another.’

Since I was twelve, I had rebelled against the idea of being a good girl, a good woman. Lives that seemed small, drab and narrow. I had given no thought to husbands or children, even though it was marriage which, in my then unexamined experience, made familial meaning. Looking back on that strange sleep-walking interregnum, all I can think is that I did not really take in what I was doing. What I was getting myself into.

The couples that made up my clannish family went everywhere together. More accurately, the women went where the men wanted them to go. It was a segregated world. There were strict, if unstated, rules about who provided what. The men made the money, and the women made the homes from which those family men went into the world in the morning and to which they returned at night. The making of the money was lauded. The making of the homes and of everything those homes made possible was rendered invisible in that process; the working men and their money appeared as if by magic.

Conflict and unfulfilled female desires were sequestered – or ridiculed. Ruptures in marital harmony were turned into oft-repeated jokes. My favourite was about the night my grandfather threatened to leave my grandmother. Granny Margaret rose from her chair in the sitting room, stalked through to the bedroom and returned with two suitcases, one in each hand. She held them out in front of her.

‘Right, Jack,’ she said, ‘which one shall I pack – the red one or the blue one?’

He slid back into his rocking chair – and that was the end of his insurrection.

It took me decades to decipher the mix of desperation in my grandmother’s brandishing of those two suitcases and the aggression in my grandfather’s capitulation. I had no comprehension of how the institution of marriage, filled as it is with the ghosts of every bride there ever was, would bend me to its will.

eight

On a sunny weekday morning in May I went in search of a wedding dress, meandering down Portobello Market on my own. Caught up in the solipsism of pregnancy, I was not lonely, and my nausea abated. For the first time in weeks I was hungry, and there ahead of me was an Italian café with tables in the sun. I sat down and the waiter brought me sparkling water and a basket of bread. I dipped the bread into the olive oil, which slid down my chin. It was delicious and my empty stomach growled for more. I scanned the items on the one-page menu. I didn’t know any of them – the only Italian food I knew was spaghetti bolognaise or lasagna drowned in white sauce topped with grated cheddar cheese burned to a crisp.

The waiter returned, his pad in one hand and a pen in the other, as if this customer was to be taken seriously. He arched an eyebrow in anticipation. I looked down at the menu, too shy to ask what the dishes were. My attention was caught by ‘Caprese tricolore’. The name made me think of revolution – the tricolour being, as I remembered, a kind of French revolutionary hat.

‘I’ll have this,’ I said.

The waiter wrote it down and went away. He would bring me what I asked for; I would give him money, and that would be that. The tricky question of eating was made simple by the transaction that takes place in a restaurant, which strips food of emotion and disentangles it from desire, obligation and shame. I could eat there by myself and for myself, not with or for anybody else – a realisation that was a gift. I would not be afraid, as I usually was, as I suspect my father was, that if I spent money on something fleeting and pleasurable – a meal and a frock instead of property or shares – money would be finished, never to return, and I would be instantaneously so poor I would be homeless and starving to death the next day.

No. On that day, I experienced a rare feeling of peace, plenitude and competence, so I did not care how much the food cost. I felt at home sitting in a café watching tourists turn trinkets over, asking ‘How much?’ and ‘Where from?’. I had the feeling I could belong in London because of the tiny seed of a baby making itself human around its giant fish-eyes and pulling me, its mother, into its orbit. That was enough.

The waiter brought a white platter and set it down in front of me with a flourish. It was a work of art. A colour wheel of food – swirls of red, white and green. The tomatoes, the cheese – the first time I met mozzarella – sliced avocado, arranged in a fan. Basil leaves, torn to release their summery smell, scattered across it all. The nausea was gone. The waiter picked up the thick linen napkin and draped it across my lap. I felt grown up enough to be a mother with such sophisticated food in front of me.

My mouth watered. I had not known I was starving. I ate every illicit expensive thing on my plate. I ordered an espresso. It was bitter but delicious.

Replete, I made my way through the market, pausing outside a shop, cloche hats draped with black netting in the window. A crocodile-skin handbag with a gold clasp brought to mind the evening bag I coveted, which my grandmother kept beside a box of brass-tipped bullets on top of the gun safe inside her bedroom cupboard.