Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

We called him a devil and quarantined him behind such labels as 'the most dangerous man alive.' But Charles Manson remains a shocking reminder of our own humanity gone awry. This astonishing book lays bare the life and the mind of a man whose acts left us horrified. His story provides an enormous amount of information about his life and how it led to the Tate-LaBianca murders, and reminds us of the complexity of the human condition. Born in the middle of the Depression to an unmarried fifteen-year-old, Manson lived through a bewildering succession of changing homes and substitute parents, until his mother finally asked the state authorities to assume his care when he was twelve. Regimented and often brutalized in juvenile homes, Manson became immersed in a life of petty theft, pimping, jail terms and court appearances that culminated in seven years of prison. Released in 1967, he suddenly found himself in the world of hippies and flower children, a world that not only accepted him, but even glorified his anti-establishment values. It was a combination that led, for reasons only Charles Manson can fully explain, to tragedy. Manson's story, distilled from seven years of interviews and examinations of his correspondence, provides sobering insight into the making of a criminal mind, and a fascinating picture of the last years of the sixties. No one who wants to understand that time, and the man who helped to bring it to a horrifying conclusion, can miss reading this book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 496

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

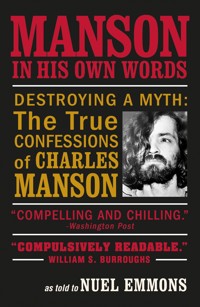

MANSON IN HIS OWN WORDS

MANSON IN HIS OWN WORDS

AS TOLD TO

Nuel Emmons

First published in the United States of America and Canada in 1986 by Grove Atlantic

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2019 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 1986 by Nuel Emmons

The moral right of Nuel Emmons to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 478 7

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 909 6

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Dedicated to destroying a myth

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART ONE

The Education of an Outlaw

PART TWO

A Circle of One

PART THREE

Without Conscience

Conclusion

MANSON IN HIS OWN WORDS

Introductionby Nuel Emmons

In late July and early August of 1969, eight of the most bizarre murders in the annals of crime surfaced. The murders were committed with the savagery of wild animals, but animals do not kill with knives and guns, nor do they scrawl out messages with their victims’ blood.

On July 31, 1969, homicide officers from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office were summoned to 946 Old Topanga Canyon Road. When they entered the premises, the officers were assailed by swarming flies and the pungent stench of decaying human flesh. They found one male body, marked by multiple stab wounds, that they established had been dead for several days. On the living room wall a short distance from the body the words “POLITICAL PIGGY” were scrawled in the victim’s blood. Also on the wall were blood smudges as though a panther had left its paw print.

The victim was Gary Hinman. Thirty-two years old, Hinman had been attending UCLA in pursuit of a Ph.D. in sociology, supporting himself by teaching music. It was later discovered that for additional income he manufactured and sold a form of mescaline.

On Saturday, August 9th at 10050 Cielo Drive in the plush residential area of Bel Air, adjacent to Beverly Hills and Hollywood, officers from the Los Angeles Police Department arrived at a second crime scene so gory it might well have come from a Hollywood horror film. There, sprawled throughout the house and grounds, were five viciously slain victims, all of whom had been in the prime of their lives. They were Sharon Tate Polanski, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, Jay Sebring and Steven Parent. And as in the Hinman house there was a bloody message. On the door of the home where the five had lost their lives, in what was later established as Miss Tate’s blood, was the word “PIG.”

The shocking massacre brought droves of reporters and photographers who surrounded the restricted area of home and grounds where police investigators sought clues. Nothing but the deaths was certain, yet. when the reporters filed their stories, speculation filled the newspapers. Some described the deaths as “ritual slayings,” others stated the killings were the result of a wild sex party, still others declared the five had died in retaliation for a drug burn. Jealousy and love triangles were also mentioned as motives. Some reporters simply stated what was known at the time; that the police were baffled about the motives for the crime and were still searching for clues in the most bizarre multiple murders ever committed in the Los Angeles area. But this was just the beginning.

On Sunday, August 10th, hardly more than twenty-four hours after the initial call summoning police to the Cielo address, the LAPD was summoned to yet another ghastly death scene: 3301 Waverly Drive in the Los Feliz district of Los Angeles, the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca.

Leno, forty-four, was dead as the result of twenty-six stab wounds, some of which were administered with a carving fork. When his body was discovered, the fork still protruded from his stomach, as did a knife from his throat. His thirty-eight-year-old wife Rosemary had been stabbed forty-one times. Again the slain victims’ home held messages boldly printed in the victims’ blood: “DEATH TO PIGS” and “RISE” on a wall, and the misspelled words “HEALTER SKELTER” on the refrigerator door. District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi would ultimately theorize that Helter Skelter explained the motive for the slayings, but for the present, everything but the nights of horror and the eight brutally assaulted bodies was a baffling mystery.

As news of the murders swept the country, newspapers, radio and television were quick to report anything associated with what soon became known to the world as “The Tate-LaBianca Slayings.” The crimes and the news coverage had a chilling effect in and around the Hollywood area. Fear and suspicion gripped the homes, hearts and streets throughout southern California. Guns and weapons were purchased for self-defense in record numbers. Police investigators, pushed to find a suspect, worked long hard hours checking clues and following leads. Although several days after Hinman’s death a suspect named Robert Beausoleil had been arrested, no one linked him to the slayings in the heart of Hollywood. It was not until months later, when a second suspect in the Hinman case was arrested, that some light would be shed on the Tate-LaBianca slayings.

That second suspect was Susan Denise Atkins, who would eventually be convicted for the previously mentioned deaths, as well as the death of one Donald Jerome (Shorty) Shea, a ninth victim whose murder did not surface until the killers were apprehended. (His body, a mystery during the trial, was not discovered until several years later.) Atkins flamboyantly confided her participation in the deaths to jail-house acquaintances, and described Charles Man-son as a charismatic cult leader, a living Jesus, a guru possessing mystical powers strong enough to entice his followers to kill for him. Atkins’ jail confidants relayed the disclosure to the police, who announced in a press conference at the beginning of December that the grisly murders of five months past were at last solved.

With Manson and several other suspects in custody, Atkins sold a copyrighted story, “Two Nights of Murder,” to The Los Angeles Times and several foreign newspapers, and before Christmas, 1969, the world read the sensational story. It, and similar stories that followed, made Manson the most publicized and discussed villain of our time, even before he went to trial. During the trial, under the persistent attention of the media, Charles Milles Manson and his followers (now described as the “Manson Family”), would gain worldwide notoriety.

Manson was charged with being the mastermind that unleashed the animal savagery in his followers. As motive for the slaughters, prosecuting attorney Bugliosi established that Manson believed, and convinced his followers, that there would eventually be an uprising by blacks against whites which Manson referred to as “Helter Skelter,” from the Beatles song of the same name. Manson was said to have ordered his followers to commit bizarre murders to accelerate this conflict, leaving false evidence to indicate that the violent acts had been committed by blacks. There was also the suggestion that Manson had chosen the Cielo Drive residence because it had formerly been occupied by Terry Melcher, a recording company executive who had failed to promote Manson’s recording efforts. When Manson initiated the killings he remembered Melcher’s “rejection” and the secluded location of his former home, making it an ideal place for murder.

The prosecution further contended that Manson had convinced his followers a pit existed in Death Valley where he and his group would be safe during the conflict between the races. Manson predicted the blacks would emerge victorious, but would not have the mental capacity to govern properly. Once the turmoil subsided, Manson and his chosen people, having grown to 144,000, would emerge from their haven and begin building a new society more in keeping with Manson’s views.

From arrest to conviction, the investigations and trials of Manson and members of the Manson Family lasted well over a year-and-a-half. Those convicted and sentenced to be executed in San Quentin’s gas chamber were: Charles Manson, Susan Atkins, Charles (Tex) Watson, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel (for the Tate-LaBianca murders), Bruce Davis and Steve Grogan (for their participation in the murder of Shorty Shea), and Bobby Beausoleil (for the murder of Gary Hinman). However, within a year after the group was sentenced to death, the State of California abolished capital punishment and the sentences were automatically commuted to life imprisonment. With the commutation the eight were eligible for parole consideration as early as 1978. In the fall of 1985, after sixteen years of confinement, Steve Grogan was released under stringent parole conditions by the California Board of Parole. To date, all others have been refused parole.

Most people see Manson and his co-defendants as callous, cold-blooded, dope-crazed killers. But others accept Manson as a leader and a guru with mystical powers. They champion Manson, defend him, and try to imitate the life he led before the murders. He has received thousands of letters and numerous visitors during his confinement: letters from teenagers and adults of both sexes; visits from women wanting Manson’s love and attention, from seekers of advice, from would-be followers. They even offer to commit crimes for him—or rather, for the myth that has grown up around him. But the myth is very different from the reality.

It happens that I knew Manson years ago, long before there were flower children and hippies. We weren’t what convicts call “joint partners,” but we did share some time and space in the same institution; Terminal Island in 1956 and 1957, where I had been sentenced on a charge of interstate transportation of a stolen vehicle. At the time, he had just turned twenty-one and I was twenty-eight. The extent of our prison association was mostly based on our mutual interest in the athletic program. However, I did see in him then what I myself had been at twenty years of age: a youth among older convicts, listening to every word the hard-core, accomplished criminals said, not yet old enough to realize the agony of a life of crime.

I was released in 1957 and shortly after opened an auto repair shop in Hollywood. Manson was released in 1958. We had mutual friends in the area and because of a problem Manson was having due to an automobile accident, one of those friends told him where I was located. Though the accident was a civil matter, it was creating other problems for Manson. “My parole officer is giving me a lot of static,” he said. “Either I fix the guy’s car I hit, or he is going to have my parole violated and send me back to the joint. Will you help me out?” I did the repairs, fixing Manson’s car as well. This incident, coupled with our having been in the same institution together, became my opportunity to record Manson’s story in his own words. For, as he has often said over the past six years, “You kept me from going to jail, Emmons. I owe you. And if anyone can explain how things came to be, maybe, because you’ve been inside, you’re the person.”

I didn’t see Manson again until 1960. We met at the McNeil Island penitentiary, where I was serving a sentence for conspiracy to import narcotics. Our relationship was much the same as it had been at Terminal Island—our contact was limited to the prison athletic programs, except for a few casual exchanges. I remember Manson once asking me if I knew about L. Ron Hubbard and Dianetics. I didn’t and had little interest in learning, so the conversation was a short one. The time served at McNeil was time that would change my life—for the better. As you will see in the following pages, it was also time that would change Manson’s life.

On my release in 1964, I wanted only to take a responsible and honest part in society. Since that time I have never infringed on the rights of others, nor have I jeopardized my personal freedom. I resumed my trade, auto repair, and later started a second career as a free-lance writer.

In 1969 I hardly noticed the Gary Hinman murder, but like the rest of the world I became very familiar with the Tate-LaBianca slayings. When Manson’s name surfaced in December of 1969, I was astonished—not because he was involved, but because this man supposed to have powers to manipulate others into carrying out his every whim bore little resemblance to the man I remembered.

By 1979 I had forgotten almost entirely about him, until one day a local publication carried a feature story on him. The writer had journeyed to Vacaville, where Manson was then confined, with the intention of interviewing him. Manson refused to permit the interview. The story was finally published using information from prison personnel, and it mentioned that Manson seldom responded to requests for interviews. I was then writing for a newspaper, and I felt that my past association with Manson might give me the opportunity to see him that had been denied others.

My first letter was answered by one of his inmate friends, who said, “Charlie gets letters all the time from assholes like you wanting to interview him. He ain’t interested in talking to you and having it all turned around and some more lies printed. But if you want to write about a wild, crazy motherfucker, send me a television and I’ll talk to you.” Enclosed in the letter were two clippings identifying the person and the murders he was serving time for. Other than returning the clippings as the writer requested, I ignored the letter.

In a second letter to Manson I identified myself enough to be certain he would remember me. I then explained that if he did not want to talk to me as a writer I would come over for just a routine visit. His reply was almost immediate, if barely legible. The essence was, “Yeah, I remember you. You should have told me who you were in your first letter and I wouldn’t have passed you off to Butch. I haven’t been having any visitors, so don’t expect too much, they say I’m crazy. But if you want to come—do what you will.” When I showed Manson’s letter to my wife, her reaction was, “Are you really going to see him? Doesn’t the thought of it give you an eerie feeling?” She, like so many others, had read the book Helter Skelter and believed very strongly that Manson had the power to lure people into his fold.

The California Medical Facility in Vacaville was only a two-hour drive from where I lived. I made the drive with thousands of thoughts racing through my mind, and several questions for each thought. I wondered which personality I would be dealing with: the young, soft-eyed, not-very-aggressive kid I remembered in prison, or the hard, wild-eyed villain the media always seemed to capture. But for all the thinking, I signed in at the institution with a complete blank on a line of conversation. Hell, I was wondering if I was in my right mind for even being there.

Signing in was an experience for me. Being at a prison again, even as a visitor, stirred memories of my days in confinement. My heart beat rapidly, and my hands trembled so badly I could hardly fill out the necessary visitor forms. Once inside, I had the urge to retrieve my pass, to head back out the gate and forget anything that was even remotely connected with a prison. Instead, I took a deep breath and took a seat among other waiting visitors.

After about forty-five minutes, the guard announced, “Visitor for Charles Manson.” At the mention of Manson, heads turned. I started toward the visiting room. Those that weren’t looking at me were craning their necks for the appearance of Manson himself. As I neared the door a guard intercepted me, saying, “No, you’ll have to come this way.” He escorted me to an area known as “between gates.” On the way, he allowed me to stop at a vending machine for some cigarettes, cokes and candy bars.

Between gates is a highly secured area that separates the front of the institution and the administrative offices from where the convicts are housed. Two electronically controlled, barred gates face each other at either end of a twenty-five foot corridor. On one side of the corridor is a room enclosed with bullet-proof glass where at least two officers control the operation of the gates and check the identification of every individual who enters or departs. Never are the two gates open at the same time. Across the corridor from the control room are two or three rooms with barred fronts. Each room is about eight feet by eight feet with a table and four stools bolted to the center of the room.

Manson had already been escorted to and locked in the room we were to use for our visit, and while the guard unlocked the door to let me in, Manson peered out, looking me over carefully. He was dressed in standard, loose-fitting blue denim prison garb with a blue and white bandana tied around his forehead to keep his long hair in place. He had a full, Christ-like beard. At that time he was forty-four years old, but other than a strand or two of grey in his beard and hair, he didn’t look much older than when I had last seen him in 1964. As the guard locked the door behind me, Man-son backtracked to the far corner of the room. He looked like a frightened, distrustful animal. With his body in a slight crouch, head a little bit forward and cocked to one side, he gave me a nod and said, “What’s up, man?” “Nothing,” I said, “I’m just here like my letter said I’d be.” With that, I placed the soft drinks and candy on the table and extended my hand for a greeting. Manson straightened his slight body, stepped toward me and took my hand. A faint smile was visible through his beard. “Yeah, Emmons,” he said, “I’d have recognized you anywhere. How’s your handball game?” “Hell, I haven’t played since I left McNeil. How’s yours?” “Fuck, are you kiddin’, that Mizz Winters [then chief psychiatrist at Vacaville] and her black boyfriends have had me locked down so tight, I don’t get to do nothin’. It took me nine years to get out of S Wing.” S Wing is a segregated unit that confines those who are still under intensive psychological observation. “They got me in W Wing now,” he added, “and that ain’t much better.”

The ice had been broken, but the room was filled with tension. Manson wouldn’t allow me within arm’s length of him, and never placed himself in a vulnerable position. He was always geared to defend himself instantly. His paranoia was even more evident when I first offered him a cigarette. “You light it!” he said. I handed him the lit cigarette, but before taking a drag, he carefully fingered the entire length of it and asked, “How far down is the bomb?” He wouldn’t touch the soft drinks or candy bars I had placed in front of him until I drank from one or took a bite of candy. He would then reach for the one I had tasted, eating or drinking only after my example had assured him that it wasn’t poisoned. “Are you putting on an act,” I asked, “or are you really so paranoid you think I’m here to poison you?” His eyes met mine in an unblinking stare as he said, “Hey look, I ain’t seen you in fifteen or twenty years. When we were in the joint together, you didn’t have the time of day for me. Now all of a sudden you show up. How do I know what you got in mind? I been alive this long ’cause I’m on top of people’s thoughts. You don’t know how bad these motherfuckers want to get rid of me. I been livin’ in their shit for ten years, and every day they send in somebody to do a number on me. I been alive this long ’cause I’m aware. I don’t trust you or anyone!”

At that moment, trying to change his opinion of me would have been wasted effort, but I did feel it necessary to explain why I hadn’t had the time of day for him when we were doing time together. “You were eight years younger than me; I had already been through all you were going through. You and the guys you lined up with in the joint were playing games and trying to impress everyone. All I wanted was to do my time and get out. It wasn’t a question of liking or disliking you.” My words seemed to calm him. The intimidating anger that had been mounting in his voice vanished and he began asking about some of our former mutual friends. As it turned out, he was much more up-to-date on their lives and whereabouts than I was. Jails have a hell of a grapevine on alumni, especially if the guy has taken another fall or is still wheeling and dealing. On the other hand, if he straightens himself out, it seems the line ends and the person might as well be dead as far as other convicts are concerned.

After about thirty minutes, the guard informed us we had five minutes remaining. During that five minutes Manson brought up what I had decided not to mention on this first visit. He said, “So you’re a writer now, huh? You know I’ve been burned by all you bastards, and I don’t trust any of you fuckers to tell the truth. Whatta you think about that?” I didn’t know if he was telling me to get lost, or if it was just his way of checking out my reaction. I answered, “That’s all right, Charlie, I don’t trust a lot of writers either. So forget I came over here looking for a story—I’m here because we’ve done some time together, and if a visit or two breaks up the monotony for you, I’ll come back. If you’d rather I didn’t, I won’t.” He didn’t give me a direct answer, but said, “Hey, I could use some stamps and writing pads, can you handle that?” “Sure,” I told him, “and if you need a few dollars on the books, I can do that too.”

Our time was up, and as we said our goodbyes he stood closer to me. We exchanged a parting handshake that held a little warmth. Neither of us had mentioned the crimes. Though he hadn’t said so, I felt he wanted me to continue visiting. Given time, I thought, some trust and confidence could develop between us.

I sent the writing material he asked for, along with some money for commissary items. We exchanged a letter or two and I began visiting almost weekly. The next couple of visits were pretty much like the first. He didn’t talk much about the outside or the past, but had plenty to say about how the prisons had changed. For a sentence or two he would be coherent—if not logical—but then he would suddenly switch subjects without completing the thought.

I wasn’t aware during the six or seven visits that first couple of months that Manson had been receiving medication until one day he said, “Maybe you’re some kind of therapy for me, ’cause they are cutting down on jabbing me with that needle.” After that, our visits became more constructive. We began talking more about the crimes. He was evasive in response to direct questions about his actual involvement, but talked freely about “his girls,” life at the Spahn Ranch, the Mojave Desert and his dune buggies. He volunteered some information about Lynette (Squeaky) Fromme and the assassination attempt on President Ford. One day, he unexpectedly asked, “You heard about Red being in Alderson, didn’t you?” (“Red” was his “color name” for Fromme; several of the main girls in the family were identified by various colors.) “I have to carry that load too. I didn’t tell her to take no shot at Ford. That was her trip, but like everything else, it’s Charlie’s fault. Hey, Charlie’s Angels on TV is even a take-off on me and my girls. By the way, do you think I sent those kids to Melcher’s house?” It was the first time he had asked outright if I thought he was guilty or not.

“You’re here, Charlie,” I said, “I have to believe some of it.” He exploded and I got my first look at those sharp, penetrating eyes that appeared so often in newspapers and on the covers of magazines during the court proceedings in 1970. He came at me, not in a physical attack, but shouting, his face inches from mine. “You motherfucker, you ain’t no friend, you’re just another victim of Sadie’s [Susan Atkins] and Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter bullshit! Fuck you, get your ass on down the road.” The guard had his keys out and was about to open the door to break up the fight he thought would surely happen, but I told the guard, “It’s all right, we’re just having a little disagreement.” The guard hesitated and Charlie backed off and glared at both of us. He was trembling with anger. Then I saw him relax, and he said to the guard, “Yeah, it’s all right, everything’s under control.” The flare of temper subsided as quickly as it had surfaced. Manson picked up the conversation in a quiet, calm tone of voice. “You know, I been around long enough to know that if you do the crime you gotta pay, but I ain’t guilty the way those pricks convicted me. So I ain’t supposed to be here! At least not under the gun the way they got me. They might have made me on conspiracy, an accessory before or after the fact; that would have carried the same sentence, and I’d be doing my time without crying.” Then quickly, for fear I might think he was showing weakness, “I ain’t crying, understand, but these fuckers are doing me wrong.” There was a moment or two of silence as his eyes bored through me in an effort to read whether I believed him or not. I broke the silence by saying, “If that’s the way it is, Charlie, let me write the book the way you say it was.” He smiled and said, “You cagey mother. After two months you finally got it out. But man, I don’t know if I can trust you.” “What’s to trust, Charlie?” I asked. “Everything bad has been said about you. But your life represents all the ills in our society and, properly illustrated, it could be an example for society. You’ve always said, Those parents sent their kids to me.’ Your life as it really was, without all that Helter Skelter bullshit that went down during your trials, could show why those kids came to you, and make parents take a look at themselves and their kids. There is a lot to be learned from the life you have lived. And besides, you have your own version of what happened to bring about the slayings. Let me write it.”

“You know what, Emmons, I don’t give a fuck about those kids out there! It’s up to their parents to take care of them. Those kids and their one-way parents are what got me here. Let them take care of themselves. No—fuck it! I ain’t into being no part of no book! Especially a book that makes me look like some do-gooder. Fuck ’em, they built the image, let them live with all these kids writing me letters wanting to visit me and join my ‘Family.’ Fuck, there was no family! Some reporter stuck that on us one time when they hassled us out at the ranch. Besides, ain’t nobody out there wants to read something they might learn from. Blood ’n guts and sex is the only trip they get behind when they’re spending their dollars.”

I left the visiting room that day feeling discouraged. I realized I’d used the wrong approach when suggesting he allow me to use his life as an example. He hated everyone in conventional society so much that he didn’t want to contribute anything that might, even remotely, be of value to society.

Several days after that particular visit, I received a letter from Manson that included two letters from publications requesting interviews with him. In his letter to me he asked if I thought he should do the interviews. Instead of writing back, I went to see him the next day. No mention of the book was made, but I told him if he was allowing interviews, let me be the first. “You got it!” he replied. “But one of these letters is from a girl from a local newspaper who has been hounding me for a long time to let her come in, so why don’t you check her out and maybe bring her with you.” We agreed that the woman and I would interview Manson together. I spoke with her and she, in turn, agreed to certain restrictions.

During the interview the reporter asked Manson, “Why do you have so much confidence in Emmons? I mean, you have refused so many interviews, but you have allowed him to interview you.” Charlie’s answer held a pleasant surprise for me. “Well, me and Emmons go back a long way. He understands me. Actually he’s one of my fathers, he helped raise me and he’s doing a book on my life.” For Manson to suggest that I had been like a father to him and had helped raise him was anything but flattering, but he had mentioned the book and I wasn’t going to press him as to why or when he had changed his mind. Perhaps he appreciated my regular visits, perhaps he recalled the favor I’d done him; whatever the case, he was willing to cooperate.

In addition to the publication I was working for, I had made arrangements with UPI to furnish their wire service with some pictures and a release on the interview. My story did not mention that Manson had agreed to furnish me information for a book, but UPI’s release said that I was writing a book on Charles Manson. I immediately began receiving letters about him. Though his crimes had been history for over a decade, Manson still attracted a startling amount of attention and interest. Most of the mail came from the United States, but there were also letters from Canada, England, Germany, Spain, Italy, and Australia. Many of them offered information for a book about Manson, all such letters suggesting that he be allowed to tell his version of his life and the chain of events that led to the slayings of 1969.

The material for this first-person narrative has been assembled from many interviews, corroborated by his correspondence with me and with others, despite numerous obstacles. Even after Man-son had agreed to cooperate, he was not always willing to do so, and I listened to hours upon hours of repetitive complaints about how rotten the prisons and the prison system were. I was allowed the use of a tape recorder only when interviewing Manson for a commissioned article for publication. On such occasions, the institution furnished me with a tape recorder because some years earlier, after an escape attempt at San Quentin, it was believed that an attorney had used his tape recorder to smuggle a gun inside. With the exception of these limited occasions, I had to make mental notes until I could record them on tape or in writing. I spent many hours in the prison parking lot, writing down names and specific phrases that typified Manson’s speech and his ideas. I frequently had to go over events with Manson several times to confirm details and correct the misperceptions created by other accounts. In some cases it was impossible to corroborate Manson’s version of the facts, but the purpose of this book is, above all, to record that version.

I pieced his childhood together with help from many sources. In addition to what he told me, which contained many gaps, I journeyed across the United States to where he was born and the places he spent the first sixteen years of his life. In Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky I talked to those who could fill in gaps and verify what Manson said. When there was new information, I would return to Manson and repeat what I had been told, to hear his words and sense his feelings about it.

What I have recorded here as a continuous chronological narrative is therefore actually the result of a long process of discussion and re-examination of the events, checking and cross-checking of details, and re-organization of the frequent, frustrating leaps of Manson’s conversation. Nevertheless, it represents Manson’s recollections of his life and his attitudes toward it as accurately, consistently, and coherently as is humanly possible.

Since my first visit with Manson, more than six years have passed. During those six years, and hundreds of hours of conversation, I have experienced his hate and contempt—and he mine. I have seen tenderness, a soft side that may well have been his strength in attracting those involved with him. But never has he demonstrated any remorse or uttered a word of compassion for those lives taken in the madness he and his group shared.

When questioned about his lack of remorse, Manson abruptly changes his attitude and aggressively defends himself: “Remorse for what? I didn’t kill those people! Ask the DA and all the media people if they have any remorse for sending all these kids to me, kids wanting to pick up knives and guns for me because the DA and the money-hungry writers pumped the public into believing I’m something I’m not. Shit, they built the image—and they keep feeding the myth.”

The myth of Charles Manson, the publicity that made him seem intriguing, the current concern about child abuse and where the use of drugs can lead all seemed important reasons to tell his story. It seems to me the myth of Charles Manson is not likely to survive the impact of his own words. They are important testimony to the consequences of the continued use of drugs, and the account they give of his early life shows once again that all children must have love and understanding. Failing to find it at home, they will search for it elsewhere. Enticed into accepting the myth of Charles Manson as reality, many people have turned to him for help.

Manson does not exaggerate the mail, visitors and potential followers who seek his attention. I have met many of them. He has forwarded to me almost two hundred pounds of mail, and sent similar quantities to others for safekeeping and review. His statement that “some are offering to pick up knives and guns” or willing to “off some pigs” for him is verified in many letters I have read addressed to Manson.

It is frightening, and most of us wonder why they do it. Manson stated, “Look at yourselves! It isn’t me or any power I have. It’s the way they were treated when they were small and their parents tried to play God. All the propaganda laid out by someone wanting to feel important and get rich gave them someone to turn to in their frustration.” He said it as clearly as it might ever be said.

With the exception of the introduction and conclusion, my opinion of Manson is not represented in this book. In letting him tell his story, I have edited it to eliminate repetition and digression, and standardized many irregularities of speech. Some names have been changed, even those mentioned elsewhere, out of consideration for those involved. But the ideas and opinions expressed here are entirely his. I have simply tried to record his story as coherently as possible, to convey his meaning as he presented it to me in his own words. And although it is his story, Charles Manson receives no royalties or any other remuneration from this book. His only recompense will be the chance to have his story heard. Although he has heard or read most of the manuscript, the final decision about what would be included and what would not has been entirely mine.

I would like to express my gratitude to Grove Press, especially Fred Jordan and Walt Bode, who dared, and helped, when others turned their backs.

Finally, to the Tates, LaBiancas, Folgers and other surviving family and friends, I apologize for opening wounds and stirring thoughts of those horrifying days in August 1969.

CHAPTER 1

ON APRIL 19, 1971, in Los Angeles, California, Charles Milles Manson heard Superior Court fudge Charles H. Older say, “It is my considered judgment that not only is the death penalty appropriate, but it is almost compelled by the circumstances. I must agree with the prosecutor that if this is not a proper case for the death penalty, what should be? The Department of Corrections is ordered to deliver you to the custody of the Warden of the State Prison of the State of California at San Quentin to be by him put to death in the manner prescribed by law of the State of California.”

In the courtroom with Manson were three co-defendants, Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten, and Patricia Krenwinkel. On March 29, 1971, a jury had found them guilty of the murders of Sharon Tate Polanski, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, fay Sebring, Steven Parent, Leno LaBianca and Rosemary LaBianca. At a later date, Manson received the same sentence for two additional murders, as did four more co-defendants: Robert Beausoleil, Charles Watson, Bruce Davis and Steve Grogan. Beausoleil was convicted for the murder of Gary Hinman, Davis and Grogan for their participation in the death of Donald (Shorty) Shea. Watson was a member of the group that did the Tate-LaBianca slayings.

—N. E.

JAILS, COURTROOMS AND PRISONS had been my life since I was twelve years old. By the time I was sixteen, I had lost all fear of anything the administration of the prison system could dish out. But convicts, being unpredictable, made it a real possibility that dying in prison would be my fate, especially when the prosecuting attorney, the media and some department of corrections officials planted seeds in the minds of other convicts by statements such as, “Due to the nature of Manson’s crimes he will be a marked man for other convicts seeking attention and notoriety.” In hearing Older pronounce the death sentence, I realized he was doing so with the full authority of the California Judicial System, yet I knew I would never be executed by the State of California. Die in prison, perhaps. But executed by the State, no!

I was right: within a year after being placed on Death Row, the existing capital punishment law was abolished in the state of California. All those awaiting execution were automatically given life terms. For most of those on the Row, it was a new lease on life. For me there was no particular elation, only the thought of, “Now what will I have to contend with?”

My paranoia has been well-founded, for due to the nature of the crimes, the amount of publicity about my arrest and the lengthy court proceedings, the name of Charles Manson has become the most hated and feared epithet of the current generation; a cross I have had to bear since my arrest in 1969. Because of the heavy security and my isolation from the general convict population, the time spent on Death Row was the most comfortable and relaxed I have spent in the last seventeen years. But since then I have been a special case in the California penal system, and because of that I’ve spent my ordinary confinement dodging spears, knives and death threats from other convicts as well as having to watch every guard who gets near me.

The latest, most newsworthy threat to my life happened in the arts and crafts room at the California Medical Facility. I was sitting on a stool facing a table, working on a clay sculpture. It was one of my first efforts at any form of sculpture and I was totally engrossed with the project—so engrossed it was one of the few times since being locked up that I relaxed my constant vigil on everything that was going on around me. I didn’t hear footsteps, nor was I conscious of anyone being near me until a cold liquid was poured over my head, soaking my hair, face and most of my clothing. Startled, I leaped to my feet and faced the direction from which the liquid came. My eyes were already burning from the substance (a highly inflammable paint thinner), so it was with blurred sight that I saw the assailant, a long-haired, bearded Krishna bastard, throw a burning match at my face. My hands weren’t quick enough to prevent the flame from making contact with the thinner, and like a bomb exploding, I was instantly a human torch. My hair, face and clothing on fire, I lunged toward my assailant. He eluded me. Pain from the flames and instinct for self-preservation didn’t allow me to continue pursuing him.

I hit the floor and pulled my burning jacket over my head in an effort to smother the ignited paint thinner. Though there was a guard and several inmates in the room, I had long ago learned not to expect help or sympathy from anyone. Not that I was thinking about what others might be doing, for at the moment my head was buzzing with what to do to extinguish the flames. I realized how vulnerable I was if the Krishna bastard decided to attack me again. But first things first, I had to get the fire out. Fortunately the guy didn’t come at me but just stood back and watched me struggle. I was aflame for forty-five seconds to a minute, long enough to have all the hair burned from my head and face. My scalp, face, neck, left shoulder, arm and hand suffered third-degree burns. I spent a few days in the hospital, a couple of them on the critical list.

The attack had nothing to do with who I am or what I am accused of. It was the result of a discussion on religion that took place the day before I became a human torch. The guy who threw the match is as flaky and disoriented about the laws of society as most people believe I am. Yet he, like myself, doesn’t see himself as some freak with a demented personality, but as a person who was dealt a hand that couldn’t be played by the rules and values of your society.

My name is Charles Milles Manson. At this writing I am fifty-one years old. If I stretch to my fullest height and cheat a little by slightly lifting my heels from the floor, I can achieve a height of five-foot-five. I think at one time I weighed a healthy hundred forty pounds, but a time or two during my confinement I have dropped as low as one-fifteen. A bulky bruising hulk I am not. But my voice can be as big and loud as the largest of men. In 1970, prior to and during the court proceedings that resulted in my conviction, I made more magazine covers and news headlines than Coca-Cola has advertisements. Most of the stories and articles written painted me as having fangs and horns from birth. They say my mother was a whore, my nose was snotty from birth and my diapers, when I had any on, were full of shit which was often seen running down my dirty legs. They would have one believe that before I was five I was a beggar on the streets, scrounging for food to feed my dirty face and fill my empty stomach. By the time I was seven, my first followers were stealing and bringing me the spoils. Before reaching nine, I had a gun in my hand and was robbing the old and feeble. Still under the age of twelve, I had raped the preacher’s daughter and choked her little brother to keep him from snitching on me. At thirteen, I had a police record that would qualify me to be on Nixon’s staff or head the Mafia. The dope I distributed had the choir boys strung out and stealing from the collection plate. In my string of brainwashed broads were the ten-and twelve-year-old girls of the neighborhood. To prove their love for me, they brought me the money they earned from turning tricks and making porno movies.

Isn’t that the way you have me framed in your thoughts? Haven’t the famed prosecuting attorney, the judges, my alleged followers, and the news media given you that picture?

Would it change things to say I had no choice in selecting my mother? Or that, being a bastard child, I was an outlaw from birth? That during those so-called formative years, I was not in control of my life? Hey listen, by the time I was old enough to think or remember, I had been shoved around and left with people who were strangers even to those I knew. Rejection, more than love and acceptance, has been a part of my life since birth. Can you relate to that? I doubt it. And this late in life, I could’nt care less! But I’ve been asked where my philosophy, bitterness, and anti-social behavior came from. So without searching to change public opinion, I’ll relate some of my life as I lived and remember it through the guy who is writing this book. You’ve read everyone else’s “Charlie’s this, Manson’s that,” and their version of the Family’s history, but nobody is ever totally all that is said or believed about him.

Books have been written, more are being written; movies made, and, undoubtedly, more in the making. The media have had a puppet to dangle and a dummy in which to plunge their swords. All have taken my words and thoughts, rephrased them, and published them with twisted meaning. Distortion, sensationalism and fabricated quotes were printed daily—so much so that life on earth no longer held valid meaning for me. Nor does it now. My body remains trapped and imprisoned by a society that creates people like me, but my mind has entered a chamber of thought that is not of this earth. I have learned that to be one’s self, one must never utter a word, make a sound or motion, or even bat an eye, for by doing so in the presence of another, an opinion will be formed. A self-styled psychologist will analyze you and describe you to others so that you become something other than what you are.

As I said, the media have had their day. Nobodies have become rich and influential. So-called “Manson Family” members have purged and turned, testifying for the State, lying in the courts. They have written books and sold interviews playing down their role, putting it all on Charlie. Lawyers on both sides of the fence have made fortunes through their association with the “Manson Family” trials. My feeling is, I’ve been raped and ravaged by society. Fucked by attorney and friends. Sucked dry by the courts. Beaten by the guards and exhibited by the prisons. Yet my words have never been printed or presented as they were said. So at this point, I have nothing to gain, or lose, by telling it the way I feel it was.

To date, thirty-seven of my fifty-one years of life have been spent in reformatories, foster homes or prisons. For the past seventeen years I have been living like a caged animal in a zoo. The cage is very much the same, concrete and steel. I am fed just as the animals are, through the bars and on schedule. I have guards patrolling my cage, making certain it is still locked and that I still live. People come to visit the institution and no matter what their other interest, all want to know, “Where is Charles Manson kept? Can we go by his cell?” And like good zoo attendants, the guards accommodate. Seeing Charles Manson in his cage, like seeing the rarest of wild animals, has made their visit complete. To satisfy my personal curiosity, I look into a mirror to see if perhaps horns are growing from my head or fangs protruding from my mouth. Unless the mirror lies, I see no horns or fangs. I check the rest of my body to see how it differs from those who stop and stare. With eyes that see, blink and stare like those who have just stopped to view, I see a body, two arms, hands and feet, and a head that grows hair in the customary places, complete with eyes, nose, ears and mouth. I’m no different from those who stopped by to give me their hated glare. Or you, who are interested in what I have to say.

If writers and other media people had stuck to the facts as disclosed by investigating law officers from the beginning, Charles Manson would not have been remembered. But with each writer, each book, or each television personality exaggerating, fabricating, reaching for sensationalism and adding hostilities of their own, myself and those who lived with me became more than what we were. Or had ever intended to be.

Most stories depicted me and those arrested with me as dope-crazed sickies. A June, 1970, issue of Rolling Stone captioned an article “A Special Report: Charles Manson—the incredible story of the most dangerous man alive.” However, there were publications that speculated that the crimes weren’t without underlying principles. For example, a February 1970 issue of Tuesday’s Child said I might be more of a revolutionary martyr than a callous killer. Naturally I, and some who shared in the madness, were quick to pick up on anything that was even remotely sympathetic.

I didn’t read either of the articles at the time although I heard much about them, but since late 1969 I have been reading similar headlines and seeing pictures of myself almost daily. All refer to me as the “hippie cult leader who programmed people to kill for him—the man responsible for the Tate-LaBianca slayings.” They established me as some kind of mystical super-being that could look into the eyes of another and make him or her carry out my every whim. I was portrayed as a regular Pied Piper who lured kids into crime and violence.

Knowing what I am, how I was raised, and all that I’ve ever been, I see those stories as ridiculous. I am dismayed at the readers who lap up the lies and believe them like the Bible, but I have to hand it to the guys who created the image—the skillful writers who can suck the most out of anything and build mountains from mole hills. I really shouldn’t blame the readers ’cause I kind of get caught up in the stories myself. But when I start believing I might really possess all the powers attributed to me and I try to work a whammy on my prison guard—he or she shuts the prison door in my face. Back to reality. I realize I am only what I’ve always been, “a half-assed nothing.”

The reason for this book is not to fight the case of “the most dangerous man alive,” if I am that (or was), but just to give the other side of an individual that has been compared with the Devil. And even the Devil, if there is a Devil, had a beginning.

I can’t remember ever hearing about old Lucifer’s mother, so I don’t know if he was born or just created as a means of putting fear in the lives of children. If he did have a mother, we have two things in common. If not, our link is that we are both used to put fear in kids’ minds. Anyway, I had a mother.

Her name was Kathleen Maddox, born in Ashland, Kentucky, and the youngest of three children from the marriage of Nancy and Charles Maddox. Mom’s parents loved her and meant well by her, but they were fanatical in their religious beliefs. Especially Grandma, who dominated the household. She was stern and unwavering in her interpretation of God’s Will, and demanded that those within her home abide by her views of God’s wishes.

According to Grandma, the display of an ankle or even an over-friendly smile to one of the opposite sex was sinful. Drinking and smoking were forbidden. Make-up was evil and only used by women of the streets. Cursing would put you in hell as quickly as stealing or committing adultery.

My grandfather worked for the B&O Railroad. He worked long hard hours, a dedicated slave to the company and his bosses. He, like Grandma, lived and preached the word of God. He was not the disciplinarian Grandma was, but, like his children, he was under his wife’s thumb. If he tried to comfort Mom with a display of affection, such as a pat on the knee or an arm around her shoulder, Grandma was quick to insinuate he was vulgar. To keep harmony between them, Grandpa let his wife rule their home. Poor man. In later years he was taken away from the home he supported and died in an asylum.

For Mom life was filled with a never-ending list of denials. From awakening in the morning until going to bed at night it was, “No Kathleen, that dress is too short. Braid your hair, don’t comb it like some hussy. Come directly home from school, don’t let me catch you talking to any boys. No, you can’t go to the school dance, we are going to church. Kathleen, you say grace. Don’t forget to say your prayers before going to bed and ask forgiveness for your sins.”

In 1933, at age fifteen, my mother ran away from home. “Was driven” might be a better description.

Other writers have portrayed Mom as a teenage whore. Because she happened to be the mother of Charles Manson, she is down-graded. I prefer to think of her as a flower-child of the 30s, thirty years ahead of the times. Her reasons for leaving home were no different than those of the kids I became involved with in the 60s. And like those kids, she chose to be homeless on the streets instead of catering to the one-sided demands of parents who view things only as they believe they should be. Some day parents will wake up. Children are not dummies; a home life is a multi-directioned street, and all ways of life should be considered and understood. As for Mom being a whore, those early teachings at home prevented her from selling her body. She did have the vanity of a whore, though, and while she was never a raging beauty, she was a pretty girl—her red hair and fair complexion made her noticed in most any surrounding. She was barely five feet in height and would consider herself fat if she got over a hundred pounds. Yet despite her vanity, physical attractiveness and display of confidence, Mom was searching for her own identity and for acceptance by others. In her search for acceptance she may have fallen in love too easily and too often, but a whore at that time? No!

In later years, because of hard knocks and tough times, she may have sold her body some. I am not about to knock her. Knowing the things I know now, I wish my mother had been smart enough to start out as a prostitute. You can sit back and say, “A statement like that is about what is expected out of Manson’s mouth,” but to me a class whore is about as honest a person as there is on earth. She has a commodity that is hers alone. She asks a price for it. If the price is agreeable, the customer is happy, the girl has her rent and grocery money and the little teenager down the street hasn’t been raped by a stiff dick without a conscience. The teenager’s parents don’t have a molested child going through life trying to live down a traumatic experience. The police don’t have a case, and the taxpayers aren’t supporting some guy in prison for umpteen years. Yes, an honest prostitute does more than help herself. She is good for the community.

On November 12, 1934, while living in Cincinnati, Ohio, unwed and only sixteen, my mother gave birth to a bastard son. Hospital records list the child as “no name Maddox.” The child—me, Charles Milles Manson—was an outlaw from birth. The guy who planted the seed was a young drugstore cowboy who called himself Colonel Scott. He was a transient laborer working on a nearby dam project, and he didn’t stick around long enough to even watch the belly rise. Father, my ass! I saw the man once or twice, so I’m told, but don’t remember his face.

The name Manson came from William Manson, a fellow Mom lived with shortly after my birth. William was considerably older than Mom, and because of his persistence they eventually got married. I don’t know if it was his way of trying to lock Mom down or if it was a moral thing because there was a kid in the house. So through him I got the name Manson. But a father—no! The marriage wasn’t one of those long-term things and I don’t remember him. Whether the divorce was his fault or Mom’s, I never did know. Probably Mom’s, she was always a pretty promiscuous little broad.

When Mom ran away from a home that had completely dominated her, she exploded into a newfound freedom. She drank a lot, loved freely, answered to no one and gave life her best shot. When I was born she had not experienced enough of life—or that newfound freedom—to take on the responsibilities of being a mother. I won’t say I was an unwanted child, but it was long before “the pill” and, like many young mothers, she was not ready to make the sacrifices required to raise a child. With or without me, Mom still had some living to do. I would be left with a relative or a hired sitter, and if things got good for her, she wouldn’t return to pick me up. Often my grandparents or other family members would have to rescue the sitter until Mom showed up. Naturally I don’t remember a lot of these things, but you know how it is; even in a family if there is something disagreeable about someone it always gets told. One of Mom’s relatives delighted in telling the story of how my mother once sold me for a pitcher of beer. Mom was in a café one afternoon with me in her lap. The waitress, a would-be mother without a child of her own, jokingly told my Mom she’d buy me from her. Mom replied, “A pitcher of beer and he’s yours.” The waitress set up the beer, Mom stuck around long enough to finish it off and left the place without me. Several days later my uncle had to search the town for the waitress and take me home.

In saying these things about my mother, I may sound as though I am selling her short, and by society’s standards her measurements aren’t up to par. But hey, I liked my mom, loved her, and if I could have picked her, I would have. She was perfect! In doing nothing for me, she made me do things for myself.