11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Jim Fraser has been at the forefront of forensic science in the UK for decades... A superb story of real-life CSI.' Dr Richard Shepherd, bestselling author of Unnatural Causes 'Powerful... Fascinating' Independent Most murders are not difficult to solve. People are usually killed by someone they know, there is usually abundant evidence and the police methods used to investigate this type of crime are highly effective. But what about the more difficult cases, where the investigation involves an unusual death, an unusual killer, or is complex or politically charged? In these cases, bringing the accused before the courts can take many years, even then, the outcome may be contentious or unresolved. In this compelling and chilling memoir, Jim Fraser draws on his personal experience as a forensic scientist and cold case reviewer to give a unique insight into some of the most notable cases that he has investigated during his forty-year career, including the deaths of Rachel Nickell, Damilola Taylor and Gareth Williams, the GCHQ code breaker. Inviting the reader into the forensic scientist's micro-world, Murder Under the Microscope reveals not only how each of these cases unfolded as a human, investigative and scientific puzzle, but also why some were solved and why others remain unsolved or controversial even to this day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

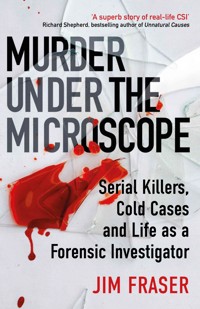

Murder Under the Microscope

Jim Fraser is a Research Professor in Forensic Science at the University of Strathclyde and a Commissioner of the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission. He has over forty years’ experience in forensic science and has worked on many high-profile cases as an expert witness and case reviewer. He has advised many public agencies including police organisations in the UK and abroad, the Home Office, the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament.

‘Jim Fraser has been at the forefront of forensic science in the UK for decades... A fascinating insight into complexities of real-life criminal investigations from their start, often at a blood-stained scene, through the complex laboratory processes to their conclusion in the court room... Totally enthralling.’

Dr Richard Shepherd, bestselling author of Unnatural Causes

‘In this fascinating account of what really went on behind the scenes of Britain’s most famous murder cases, Fraser slides not just the evidence, but the whole criminal legal system, squarely under his forensic microscope. Everyone interested in justice – how it works, and how it fails – should read this compelling book.’

Sarah Langford, bestselling author of In Your Defence

‘In this engrossing and accessible professional memoir, Jim Fraser opens his forensic files and offers the reader a fascinating insight into some of the most notorious cases that he has worked on during his lifetime.’

David Wilson, Emeritus Professor of CriminologyBirmingham City University

‘Absolutely fascinating… Murder Under the Microscope should be on every crime writer’s shelf.’

Sam Blake, bestselling author of The Dark Room

‘This is a page-turning read but also an educational resource: the public, police, lawyers, judges, scientists should all read it. It is a raw account of the fragility of justice: a concept many talk about but few understand. And it is about truth: the limitations of our own judgments, science and the law. It is probably one of the most important criminal justice texts of our time... For those working in the criminal justice system, it should be mandatory reading.’

Simon McKay, Barrister

‘This memoir from a forensic scientist and cold case reviewer makes for absolutely fascinating, and rather chilling reading… Jim Fraser is at times damning, highlighting the downfalls of the system. It is quite obvious that with financial restraints, different systems, and human foibles, mistakes will be made, and when a life is at stake it is hard to swallow. Murder Under the Microscope offers a compelling window into a world that most know little about.’

Liz Robinson, LoveReading

‘This “personal history of homicide” is the latest in a recent spate of excellent books from the forensic profession… Fraser microscopes in on the information contained in tiny details, explains the correct way to handle it, and shows how it can affect an investigation’s outcome.’

Strong Words

By the same author

Forensic Science: A Very Short Introduction

Handbook of Forensic Science (with Robin Williams)

Murder Underthe Microscope

Serial Killers, Cold Cases and Life as a Forensic Investigator

Jim Fraser

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © James Fraser, 2020

The moral right of James Fraser to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-596-9

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-595-2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ralph Skinner

12 October 1965–24 August 2017

History (hi.stori), sb. [Ad. L.historia narrative of past events, an account, tale, story, a. Gr.ἱστορία] a learning or knowing by inquiry, an account of one’s inquiries … 1. A relation of incidents … narrative, tale, story.

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Preface

Introduction

1. Robert Black, the Killer of Childhood

2. The Many Roads to Justice

3. The Chillenden Murders

4. The Trials of Michael Stone

5. The Murder of Wendy Sewell

6. The Murder of Damilola Taylor

7. Silent Testimony – ‘Every Contact Leaves a Trace’

8. The Mystery Sweatshirt

9. On Wimbledon Common – the Murder of Rachel Nickell

10. Operations Edzell and Ecclestone

11. Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

12. The Cryptic Death of Gareth Williams

13. If In Doubt, Think Murder

Conclusion: The Killer of Little Shepherds

Afterword

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

Author’s Note

This book melds recollection with reflection and, with the passing of time, the accumulation of richer experience and of course the benefit of hindsight. My memory has been supplemented with research, including publicly available material, an unsystematic collection of notes, diaries and documents accumulated over the years and conversations with individuals. I have made every effort to check facts, but any errors that remain are mine. In most instances I have altered the names of individuals to preserve anonymity. I have used real names when the person is readily identifiable or has given permission. Most of the dialogue is re-created from memory, but some comes directly from notes or transcripts. My aim is to reproduce the character and content of dialogue rather than the literal words.

According to Janet Malcolm, the writer and journalist, ‘Every journalist [when writing about murder] who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.’1 I am not a journalist but it seems to me that there must be an element of truth in Malcolm’s view; many accounts of murders appear to be inherently gratuitous and problematic. This raises for me a gnawing question, arguably a duty to justify my work. This is all the more acute because my experience is so indirect that I cannot do justice to the many victims in these cases. Nor is this something that I feel able to clarify with any richness; I simply felt that these were stories that needed to be told. I have written about these cases because I believe they are experiences that ought to be shared, and in a manner that explicates, clarifies and counters the superficial, technophilic simplicity of the many institutionally curated accounts of murder investigation. I firmly believe that only by weeding the forested thickets of myths and ignorance around the topic can we learn from these experiences.

Preface

‘Working on an interesting case?’ I asked my colleague sitting opposite me.

She looked up from her microscope. ‘Not really,’ she replied. ‘There’s blood on the knife matching the victim and cuts in the victim’s shirt that the knife could have made. The suspect denies it but his fingerprints are on the knife. It’s the usual murder stuff.’ She smiled and went back to what she was doing.

I have worked as a forensic scientist for over forty years, during which I have dealt with some of the most terrible murders. The murder detection rate in the UK is about 85 per cent and most murders are not difficult to solve. There are three reasons for this. First, most people are killed by someone they know; the killer will be found within a small group of family, friends and acquaintances. Second, the crime is the end point of an escalating series of events that usually leaves behind abundant evidence. Finally, the police methods used to investigate this type of murder are highly effective.

Most of the murders I have worked on were pushed from memory to be replaced by others in my busy operational role. I gave evidence in only a small proportion of cases and it was rare for me to get to know the outcome of any trial. Apart from my memories, my only record of these cases, if I have one, is a line in a notebook or diary recording the date I attended the crime scene or court. My involvement was, in the end, relatively superficial, as was my knowledge of the case. The public profile of these cases also diminished, leaving the individuals directly involved to deal with their impact and loss. The cases in this book are different, for many reasons; they involve serial killers (very rare), child victims, miscarriages of justice, poor investigations or police misconduct, or they remain unresolved or contentious. All have attracted a great deal of attention from the media. My level of involvement was also very different. I was much more closely engaged, sometimes over a very long period, and I had extensive and detailed information about the investigation. I knew these cases intimately and had some sense of their often tangled trajectories.

A common theme in all of these inquiries is that they are multi-layered; small stories are enclosed in bigger stories that in turn are enclosed in yet bigger stories, like a set of Matryoshka dolls. In this book, I deal with three layers. The outermost layer could be called ‘societal’. These are the biggest stories; public stories of expectations and beliefs, right and wrong, good and evil, justice and injustice. I do not spend much time on this layer, but all of the cases have some element of it.

The middle layer is what we might call ‘institutional’; the systems that deal with murder investigation – for our purposes primarily the criminal justice system (CJS).* The CJS generally presents us with an image of procedural rectitude, but these cases reveal a different reality under this polished veneer. Although the CJS produces a binary output of guilt or innocence,* this does not come from a mechanical or algorithmic calculus, but from something more organic and gelatinous. Component parts collide and merge in a loosely linked, constantly moving network, like distributed ganglia in some vast primitive organism. The CJS is all periphery and no centre, a system that is not a system,1 a system that no single individual fully understands. Organisations cooperate or clash, muddle along or fail. My viewpoint of the CJS is narrow, framed by science and technology, a peripheral domain that is sometimes valorised, sometimes condemned. Science and technology in this context does not stand alone; it relies on human action, knowledge, imagination and fairness. It can also be attenuated by human inaction, ignorance, failure or prejudice.

The innermost layer of this book is the individual perspective; my individual perspective from my direct involvement in these cases. I have spent much of my working life looking down microscopes: low-power microscopes, high-power microscopes, polarising microscopes, comparison microscopes and microscopes connected to other scientific instruments that analyse colour or chemical structure. Looking at everyday things under a low-power microscope reveals an extraordinary micro-world. The surface of clothing yields an exotic array of particles: fibres from the clothing itself and the items it has been in contact with, such as other clothing, furniture, bedding; hairs from you, your family and acquaintances; fibres and hairs from seats in your car; hairs from animals; minute quantities of skin or dust; sparkling fragments of minerals and crystals from domestic products, such as sugar or salt; glass fragments, particles of foodstuffs, plants and insects.

But low magnification only takes you so far. Like scanning the horizon with binoculars, it shows the trees and other features but does not identify them individually. Increase magnification a level and some of the debris can be more clearly seen. It becomes possible to distinguish different types of fibres and hairs, although it is hard to keep things in focus; they tremble and disappear when you try to pick them up with forceps. They are also more difficult to find. It’s rather like trying to locate a star in the night sky with binoculars. At higher magnifications, the Petri dish containing the debris takes on the proportions of an airport long-stay car park, with vast areas to search. Sometimes you look straight at the thing you are hunting for but don’t realise it because it completely fills the field in front of your eyes, like a giant cinema screen. You can’t see the trees for the wood. In this world of higher magnification, it is easy to get lost. And if you don’t know what you are looking for, you can’t operate. You can’t search for fibres when you don’t know what colour they are.

The cases in this book are under the microscope. For most murders, those that are quickly resolved, low magnification suffices. But when the police investigate the more difficult homicides, or unexplained deaths, they enter the equivalent of the forensic scientist’s micro-world. The more closely they look, the more they find, and the more detail they see. It becomes harder to stay focused and what they discover becomes more complicated and contradictory. Sometimes they don’t know what they are looking for; but not looking is not an option. These cases can become so saturated with information, so fogged with detail that sometimes no sense can be made of them. There is so much inchoate data that logic and reason are overwhelmed.

These are cases that have puzzled me for many years, and I have written about them in an effort to understand them and see what they tell us about the business of homicide investigation. The book moves constantly between the institutional and individual perspectives. We shift from one lens to a second and occasionally a third. Having worked on these cases, I thought I knew their stories. I was wrong.

_____________________

* There are many important elements to the criminal justice system – social work, prisons, parole boards – but I confine myself to those I have had some involvement with; primarily the police and the courts.

* Strictly speaking, not guilty. And of course in Scotland there is the unique verdict of not proven.

Introduction

I crouched over the body of the man lying in the doorway and slowly scanned around his head with the soft bright light from my lamp. Bloodstain spatters radiated outwards onto the wall and the pavement. The congruence between the bloodstain patterns and the position of the body was unmistakable; he had been repeatedly attacked where he lay. I turned to look at the trail of blood along the pavement and saw the crime scene manager walking towards me. I had just arrived; we hadn’t spoken yet.

‘What do you think?’ he asked.

‘I think I’m going to be here for a while examining the blood patterns,’ I replied.

‘The DI thinks he fell.’ He pointed to a first-floor window above where the body lay.

‘Maybe.’ I nodded. ‘But then somebody gave him a good kicking.’

The analogy of an unassembled jigsaw puzzle as a crime investigation is as inaccurate as it is clichéd. Even a straightforward investigation is an unfolding drama in time and space. You never have all the pieces, nor do you need them. Instead you must decide what is likely to be important and find those pieces – witnesses, or items of evidence such as drugs or weapons. From this evidence you need to construct a picture; more accurately, a story. Even then, the pieces may not give you the image you expect. An emerging picture that resembles one thing can change to something else as other pieces are added. And the picture that does explain the case will look different to different people: like the Necker cube or the ‘old wife/young mistress’ illusion.

A cryptic crossword puzzle is a better analogy; you have to solve individual clues, not just assemble them, and there is more scope for error and misinterpretation. Sometimes incorrect answers can falsely corroborate each other. But even this analogy breaks down, because the aim with a crossword puzzle is to answer every clue, to achieve a perfect solution. There is no need for a perfect solution to a murder investigation, no need to find every clue; just enough to present a credible prosecution and eliminate reasonable alternative explanations. Nor does the crossword analogy capture the sense of binary choices that an investigation can present; things not done that once forgone can never be recovered, the choice of bifurcations in a road that are lost once the alternative is chosen.

Crouching over the body that morning, I was presented with the clearest of evidence that the death was a murder. The man may have had some hidden pathology in his body that I couldn’t know of that was connected with his death, but when he was being kicked, he was still alive, his heart was beating, his blood was flowing; otherwise I would not have seen the bloodstain patterns that were around him. If I had packed up my stuff and left, this evidence would have been lost.1 Some hours after I had completed my scene examination, news filtered back from the autopsy that the man had multiple head injuries that could not have been caused by a fall.

At the start of a death investigation it is essential to balance all the possible explanations until one emerges as dominant: accident, suicide, homicide, murder. A forensic strategy identifies the central questions in an investigation and links them to forensic examinations that might resolve them. In most cases, like the example above, many of the questions are obvious. How did the person die? How did they come to be where they were found? Is there anything that makes the circumstances immediately suspicious? The questions are obvious but the answers may not be. At the outset, in the so-called ‘golden hour’,* much depends on the experience, knowledge and attitude of those addressing them. The person dealing with the investigation at that stage could be an inexperienced on-call detective. We are fed the solo investigator myth so widely that even those who do the job sometimes forget that they are part of a system where support and advice are available. One wrong decision can take an investigation down a road from which it may never recover and murder is written off as an accident or suicide. A Home Office study in 20152 identified a worrying number of cases that had been identified as murders after they had initially been categorised as non-suspicious. The main reason for the wrong decision was a lack of knowledge and bias of those first attending the scene.

Even a delay in the early stages of the investigation can be a problem; witnesses vanish and forensic evidence is lost, leaving important questions impossible to answer. There is still scope for error once an investigation is stabilised, but there are more opportunities for fatal error at the outset.

Much of what we believe about murder investigation has been shaped by history and mythology. Around 1850, at the height of the public frenzy about the new individuals called ‘detectives’, Charles Dickens wrote about the ‘science of detection’ and the special skills that the detective was assumed to possess.3 Are detectives exceptional individuals with skills and procedures that no one else has? Few believe this now, but a great deal of mythology shrouds these issues, much of which is created by those involved. Only a tiny proportion of people, mainly those with direct experience, get to know what actually goes on in an investigation. How many people have been to a courtroom or a crime scene? How many to a forensic science lab? Our information comes second-hand, filtered, presented and represented, partial; continually reinforcing the mythology. From the time of Dickens until now, little has changed. How murder is investigated comes to us more from imagination than from experience or fact.

The modern extension of the detective myth is best exemplified by the TV series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. CSI makes such good TV because of its stories, characters and puzzles, and perhaps above all the style and visuals that accompany them.4 It blends the detective myth with the mythology of science: objectivity, logical reasoning and truth; truth that cannot be seen by the eye, that can only be revealed by technology, that requires an expert for it to be found and understood. This, of course, is artistic licence, entertaining but oversimplified gloss, sometimes nonsense. CSI gives us a science that benevolently serves criminal justice – a belief-based science.

It’s not only fiction that deals in stereotypes. I’ll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara5 is a detailed account of the investigations into the Golden State Killer,* who was active in California between 1974 and 1986. It is well written and researched and reads more like a thriller. But even here, light and shade is lost and Day-Glo colours are used when the author compares detectives and forensic scientists: ‘Cops thrive on action. They are knee jigglers … The crime lab is arid … there’s no hard-edged banter … Cops wrestle up close with life’s messiness; criminalists† quantify it.’ These are matchstick figures, a convenient shorthand but lacking in nuance. Such stereotypes also feed the mythology; it thrives still.

I spent the first 18 years of my career as a laboratory-based forensic scientist, scene investigator and expert witness in London and Edinburgh. I spent eight years as head of forensic investigation for Kent Police, running a large department, advising senior investigating officers (SIOs), reviewing cases and working on national projects. I spent 12 years as an academic, researching, teaching, reviewing cases and advising police organisations and governments. I have been involved in hundreds of murder investigations. Am I a ‘quantifier’ or a ‘knee jiggler’? Neither is accurate, it seems to me.

‘You don’t talk like a scientist, you talk like an investigator,’ said an Australian police officer I met when I was reviewing a case in Melbourne. I thought it was a compliment. Some forensic scientists would think not. Some detectives would be appalled at the idea of anyone other than a police officer being considered an investigator. Others would agree, because they are not confused by the artificial boundaries, the stereotypes. I want to cut through these stereotypes and mythologies, because only by doing so can the world I want to describe be understood.

This is neither a systematic nor a scholarly work, although it does have a logical rationale. Most murders are solved quickly and go through the courts speedily. When there is a guilty plea, or plenty of evidence, as there usually is, the full details rarely leave the courtroom. These are tragic events for a small group of individuals, but publicly we hear little more about them. The drama, pain, twists and turns of the story remain buried. When such details are left untold, at least to those not directly involved, it is difficult to know what aspects of the trial were salient. I want to explore these investigations in order to better understand them. I also want to enable the reader to draw their own conclusions about what these cases tell us; to achieve this, I need to point out some recurrent features of significance that will aid understanding. There is a difference between what an institution – for example, the police* – says it does and what it actually does. We need to apply this sense of actualité to the three domains involved in murder investigation: forensic science, the police, and the criminal law and courtroom. How much weight is given to each of these domains varies from case to case, determined by the individual story.

Forensic science, our first domain, is a term that cloaks a ragged patchwork of assertions and beliefs. It covers activities that are unquestionably scientific as well as those that are unquestionably subjective or entirely intuitive. There is no single thing that can be straightforwardly categorised as forensic science. It is an ill-defined collective. If we consider ‘real’ science to be the stuff that qualified, professional scientists do in laboratories using specialist equipment and procedures,* this leaves a large number of individuals in other roles commonly tagged under ‘forensic science’ who are neither scientists nor do any scientific work: fingerprints experts, crime-scene investigators, crime-scene managers and others. Nor is all of the work done by the people in white coats entirely scientific.

A good example of the kind of quasi-scientific work carried out by some forensic scientists (including me) is bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA), which crops up in several cases in this book. BPA has a scientific foundation and some elements of it can be considered to be objective. But a great deal of the BPA work done at crime scenes is completely reliant on subjective information, without which there can be no interpretation and therefore no evidence. Why does this matter? It matters because the courts and others accord science a higher, perhaps the highest, status as a source of knowledge (and therefore evidence). Deciding what is and what is not science is important.

There is a myth that scientific evidence speaks for itself; that it is somehow free from the frailties of human agency, and that it occupies a special and incontestable place in the evidential canon. The modern origins of this idea can be traced back to nineteenth-century France, although it could have arisen earlier. Dr Alexandre Lacassagne, professor of legal medicine at the University of Lyon,* was amongst the first to see the potential of scientific and medical evidence to overcome some of the weaknesses of witness testimony: poor memory, prejudice and mendacity. He introduced a rational approach to homicide investigations that took into account observations and findings from crime scenes and post-mortem examinations. He coined the term ‘silent testimony’ to describe this new type of evidence.

One of his students, Dr Edmond Locard, nowadays more famous than his master, supplemented Lacassagne’s idea with what is now widely referred to as Locard’s exchange principle: ‘Every contact leaves a trace.’† In 1953, Paul Kirk, an American forensic scientist, took Lacassagne’s idea of silent testimony and Locard’s principle of exchange and stretched them into one of the most pervasive myths of modern forensic science: that forensic science has all the answers, always.

Wherever [the criminal] steps, whatever he touches, whatever he leaves, even unconsciously, will serve as a silent witness against him. Not only his fingerprints or his footprints, but his hair, the fibres from his clothes, the glass he breaks, the tool mark he leaves, the paint he scratches, the blood or semen he deposits or collects. All of these, and more, bear mute witness against him. This is evidence that does not forget. It is not confused by the excitement of the moment. It is not absent because human witnesses are. It is factual evidence. Physical evidence cannot be wrong, it cannot perjure itself, it cannot be wholly absent. Only human failure to find it, study and understand it can diminish its value.6

This is not science, or rationality for that matter, but mythical dogma portraying forensic science as a utopian project that can only be corrupted by humans. Yet whatever forensic science is, it can only be fulfilled by humans. It is true that humans can mess things up. But it is also true that it is humans that make forensic science and investigations work. It makes no sense to describe what might be achieved if it were not for humans.

Our second domain is the institution of the police. There are many myths about how the police operate, which can be grouped under the heading of ‘police culture’. One of these is procedural integrity or thoroughness; following the rules. However, the police, although very good at producing documented procedures, are actually quite poor at following them, even their own.7 There are many practice manuals and policies in existence throughout the police service in the UK, but their role is often symbolic, or at best a rough guide to what might get done. The police delight in improvisation. For example, what was going through the minds of the detectives in the Jill Dando case (see p.215) when they opened the sealed packaging of a critical exhibit and compromised the forensic evidence in a case of great public interest and significance? I find it impossible to believe that they did not know what they were doing, and equally impossible to understand why they did it. If you find this surprising, you will come across even more extraordinary lapses in procedure in more than one case in this book.

Another aspect of police culture that is not widely appreciated is the preference for action over reflection. Action and being seen to act can be an end in itself; it relieves anxieties, avoids deliberation and is a visible signal that something is being done.

Finally, how the police use science and technology is an ongoing theme. Counterintuitive though it may seem, the police have quite a limited understanding of science and technology generally, and forensic science in particular. Furthermore, how they choose what technologies to employ and how they then use them is heavily influenced, even distorted, by police culture. If you can accept this, the mist will disperse. The current debate about real-time facial identification – how effective it is and whether it is ethical or legal to use it – is a good illustration of these issues.

Our third domain is the criminal trial, those ‘great reckonings in little rooms’8 that are such a dominant feature in the work of a forensic scientist. In my experience, the courts are theatres where the rational and the absurd compete for attention. If health and safety rules allowed it, I feel sure forensic scientists would be expected to wear white lab coats in the witness box; the symbolism and rhetorical power of such an image would be too much for the advocates to resist. Although it is rare for forensic scientists to appear in court, even as operational experts, the courtroom is a constant presence. All prior activities and considerations are framed with reference to this imagined future event. In the mind of an expert witness, it provides a continuous stream of narrative and counter-narrative, argument and counter-argument, guess and second-guess, determining choices, actions and judgements. This is also a significant feature of detective work; a recurrent theme of investigations is deciding what is to be attended to, what is to be chosen, prioritised, acted on or rejected on the route to resolving a case, with the trial in mind.

These three domains influence how police investigations, forensic work and trials are imagined, structured and operate. They interact, sometimes productively, sometimes destructively, in terms of the procedures, beliefs and epistemologies of the institutions involved.

—

The small selection of cases in this book are a snapshot from the thousands I have worked on, and are arguably exceptional. All have a public face and profile and have engaged and continue to engage a broader audience. They have been the subject of books, TV dramas and documentaries. There are websites and web forums about some of them. They have been pored over, picked apart and argued about. Their stories and their main characters have become public knowledge; they have an additional dimension. This information and the detail they reveal is rarely available; these cases can tell us in a direct way about how murder investigations happen, a way that can be reflected upon and from which we can learn.

The reasons for the public face of these cases vary but include the particular nature of the crime, the characteristics of the victim or the offender, the effectiveness or otherwise of the investigation and the fairness of the conviction. But none of these bland words captures the public emotion or drama involved when a crime is so horrific that its details can only be hinted at by media, when women and children are murdered, when a serial killer, whose mind is so different from our own that we can scarcely conceive of it, is on the loose, when errors are made that allow the guilty to escape justice, when the evidence for conviction appears so thin that views are divided as to its significance.

My direct experience of these cases was deep but narrow, exposing a particular view that sometimes made sense but more often did not. In this book, I explore them from the near distance, from shifting viewpoints and from the lived experience; what I recall and have established actually took place. Having undertaken this work, I am much better informed; still fascinated, yet still a bit puzzled.

_____________________

* This is a much-used cliché but one that holds some truth. It means the early stages of a homicide investigation, before key evidence might be lost. No one seems to agree how long this period is, but I have seen suggestions that it is as long as 72 hours.

* Also known as the Eastern Area Rapist, the perpetrator is believed to have committed at least 13 murders, 50 rapes and over 100 burglaries.

† A common term in the USA that in this instance means a forensic scientist.

* For clarity, this notion applies to all institutions, from the military to the Church.

* This is, of course, a huge oversimplification of what science is but is fine for our purposes.

* Lacassagne’s school in Lyon operated from 1855 to 1914.

† What Locard actually wrote was ‘Any action of an individual, and obviously the violent action constituting a crime, cannot occur without leaving a trace.’

CHAPTER ONE

Robert Black, the Killer of Childhood

[Each attack was] accomplished in the same circumstances, executed in the same way, and showed an identical operating procedure.

Alexandre Lacassagne1

As a child back in the sixties, I used to walk to primary school on my own. It was safe, and no one worried. Fewer than half of today’s kids walk to school, and almost all of them are accompanied by an adult. The main reason parents give for accompanying children is dangerous traffic. The second most common reason, cited by almost one third of parents, is fear of assault or molestation; ‘stranger danger’. Robert Black, a man now largely forgotten, is possibly more responsible for this change in parental behaviour than any other single person.

In July 1990, Black had attempted to abduct a six-year-old girl in broad daylight in the Borders village of Stow. A local man saw a blue Ford Transit van slowing to a stop on the roadside opposite him, its wheels partly on the pavement. He saw the girl’s legs disappear as she walked past the van; she didn’t reappear. The van then pulled away violently onto the correct side of the road and drove off north, towards Edinburgh. This witness called the police.

Constable John Wilson was one of the officers who responded to the alert and was by the roadside when he saw a blue van travelling south back into the village. He stepped out into the road and flagged it down. The driver of the van was aged about 40, bearded and balding. Wilson opened the side door and found the missing child in two overlapped sleeping bags. Her head had been pushed towards the bottom of the outer bag and the drawstring of the inner bag was tightened around her neck. Her hands were bound and she had sticking plaster over her mouth. As the child gasped for air, he recognised his own daughter.

In August 1990, Black was convicted of the abduction of Mandy Wilson and sentenced to life imprisonment at the High Court in Edinburgh. His arrest and conviction led to a child murder investigation on an unprecedented scale. He was suspected of abducting and murdering 11 children; seven in the UK and four in continental Europe. There were also a number of other abductions and assaults that fitted his modus operandi. A meeting was convened in Edinburgh for those UK police forces that believed he might be a suspect in any of their cases. By the end of the meeting, four cases were identified as being the main priorities of the investigation: the murders of Susan Maxwell, Caroline Hogg and Sarah Harper, and the attempted kidnap of Teresa Thornhill.

In July 1982, eight years before Black’s arrest, 11-year-old Susan Maxwell went missing on her way home from playing tennis. She lived in Cornhill-on-Tweed, near the border between Scotland and England. Her body was found 12 days later, 250 miles away in Staffordshire. She had been raped and strangled. Her tennis racket and ball, blue plastic thermos flask and one of her shoes were missing.

Five-year-old Caroline Hogg went missing one evening in July 1983 from Portobello, near Edinburgh. Her naked body was found 10 days later in a ditch in Leicestershire, almost 300 miles away. She was so badly decomposed that the cause of death could not be established. Her lilac and white gingham dress, underskirt, pants, socks and trainers were never found.

In March 1986, 10-year-old Sarah Harper disappeared after going to buy a loaf of bread from her corner shop in Leeds. Her body was found a month later in the River Trent near Nottingham. Her pale blue anorak, pink skirt, shoes and socks were missing.

In April 1988, a man tried to kidnap 15-year-old Teresa Thornhill and force her into a blue van. Teresa was older than the murdered girls but was slightly built and looked younger. She managed to fight off her attacker with the help of her boyfriend.

All these cases had striking similarities to the abduction of Mandy Wilson. Black’s snatch of the young girl in broad daylight had been meticulously planned. He carried equipment – sleeping bags, duct tape and other items – for this purpose. The three murdered children had vanished without trace, and two of their bodies had been found in similar locations. Six police forces were now involved in the investigation: Lothian and Borders, West Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and Northumbria.

I had joined Lothian and Borders Police* in Edinburgh in 1989, after 11 years with the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science laboratory in London. At the time, the Met lab was one of the largest in the world, with more than 300 staff. My notebook records my first murder case in 1981, and a total of 62 by the time I left London eight years later. A crude analysis of these cases shows the most common method of killing as stabbing (22), with shooting and strangulation in joint second place (six each). Some of the cases are still unsolved, but there were no child murders recorded, and no serial murder cases.

Lothian and Borders was the second largest force in Scotland but was small by UK standards. I wasn’t anticipating new opportunities in Edinburgh, but I needed a change. Although London was an exciting environment to operate in professionally, the management in the lab I worked in was stifling. The people in Edinburgh would be different and the problems would be different. I was head of biology in one of the smallest forensic science laboratories in the UK, with only 15 staff. The biology section had four full-time scientists, including me.

When I learned of Black’s modus operandi, I thought about my own young children. How could I protect them from a man like that? My impulse was to jump in the car, drive to their school, take them home and lock them in. Only then would they be safe.

—