9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Sayed Kashua has been lauded by the New York Times as "a master of subtle nuance in dealing with both Arab and Jewish society." A Palestinian-Israeli who lived in Jerusalem for most of his life, Kashua started writing with the hope of creating one story that both sides could relate to. He devoted his novels and his satirical column in Haaretz to exploring the contradictions of modern Israel while also capturing the nuances of everyday family life in all its tenderness and chaos. Over the last decade, his humorous essays have been among the most widely read in Israel. He writes about fatherhood and marriage, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and encounters with prejudice, as well as his love of literature. With an intimate tone fueled by deep-seated apprehension and razor-sharp wit, he has documented his own life as well as that of society at large - from instructing his daughter on when it's appropriate to speak Arabic (everywhere, anytime, except at the entrance to a mall) to opening a Facebook account during the Arab Spring (so that he wouldn't miss the next revolution).From the events of his everyday life, Kashua brings forth a series of brilliant, caustic, wry, and fearless reflections on social and cultural dynamics as experienced by someone who straddles two societies. Amusing and sincere, Native - a selection of his popular columns - is comprised of unrestrained, profoundly thoughtful personal dispatches.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

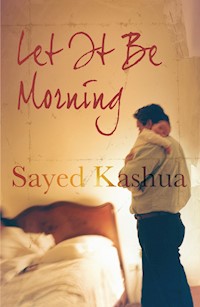

SAYED KASHUA is the author of the novels Dancing Arabs, Let It Be Morning, which was shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and Exposure, winner of the prestigious Bernstein Prize. He is a columnist for Haaretz and the creator of the popular, prizewinning sitcom, Arab Labor. Kashua has received numerous awards for his journalism including the Lessing Prize for Critic (Germany) and the SFJFF Freedom of Expression Award (USA). Now living in the United States with his family, he teaches at the University of Illinois.

“Being a Palestinian who was born and raised in Israel, Kashua is an embodiment of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. If he only was a little less sincere, perceptive, and talented he would have probably been able to coexist with himself. Native is a book that will make you lose most hope in the power of national processes but, at the same time, will leave you in awe of the incredible force of humanity, humor, and some damn good writing.”ETGAR KERET, author of THE SEVEN GOOD YEARS

“Kashua’s columns are conversational, confiding, anecdotal, centered on the rituals and trials of bourgeois life . . . While his writing is rarely explicitly political, a sense of uprootedness lurks.”NEW YORKER

“By turns funny, angry, and moving, Kashua’s ‘dispatches’ offer revealing glimpses into the meanings of family and fatherhood and provide keen insight into the deeply rooted complexities of a tragic conflict. A wickedly ironic but humane collection.”KIRKUS REVIEWS

“Startling and insightful . . . Kashua’s subtly shaded, necessarily complex, and ultimately despairing account of the tensions within his homeland, ‘so beloved and so cursed,’ is bound to open the eyes and awaken the sympathies of a new swath of loyal readers.”PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“Just when you think everything that can be said about the Middle East has been said, Sayed Kashua brings us this remarkable book. At once hilarious and tragic, rueful and sweet, absurd and insightful, it should be required reading for anyone who thinks they know anything at all about Palestine and Israel.”AYELET WALDMAN, author of LOVE AND TREASURE

“Kashua simply narrates, column after column, the impossibility of living as an Arab in the Jewish state. . . . This is among the most justified collections of newspaper columns ever published.”HAARETZ

“The writer’s new collection of personal essays and newspaper columns will make you laugh until you cry. . . . funny, tragic, illuminating. . . . [Kashua] is a humorist, writing about the small change of everyday life in a spirit of amused resignation. . . . His comedy is a kind of humanism, based on the principle that people all basically have the same weaknesses and foibles.”ADAM KIRSCH, TABLET MAGAZINE

“Bone-dry, understated . . . Kashua strikes me more like Jerusalem’s version of Charles Bukowski. A chain-smoking, drunk, constipated cataloger of life’s daily ills, illustrating through the simplest of social transactions how complicated a life can become when the threads of it start slipping away from you.”JASON SHEEHAN, NPR.COM

NATIVE

Dispatches from a Palestinian-Israeli Life

SAYED KASHUA

Translated from the Hebrew by Ralph Mandel

SAQI

Published in Great Britain 2016 by Saqi Books

Copyright © 2016 Sayed Kashua

Translation © 2014 Haaretz

Sayed Kashua has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The author owes a great debt of thanks to Haaretz, which published the columns in this collection in their original form.

First published as Ben Haaretz by Keter Publishing House in 2015.

ISBN 978-0-86356-196-2

eISBN 978-0-86356-186-3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

SAQI BOOKS

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

To my wife, Najat; and my kids: Nai, Emil, and Neil

CONTENTS

Introduction

Part I: Warning Signs (2006–2007)

Warning Signs

High Tech

Head Start

I, the Jury

Happy Birthday

Holiday in Tel Aviv

I Stand Accused

Unseamly

Happy Holiday

Instead of a Story

Stage Fright

Do You Love Me?

Nouveau Riche

My Investment Advice

A Room of My Own

The Next Big Thing

Yes, I Don’t Want To

The Bicycle

Vox Populi

Part II: Foreign Passports (2008–2010)

Foreign Passports

Sayed’s Theater

Rabbit Monster

Home Again

New Deal

Taking Notice

Land of Unlimited Possibilities

Good Morning, Israel

Superman and Me

Bar-Side Banter

Cry Me a River

Kashua’s Complaint

Part III: Antihero (2010–2012)

Antihero

Castles in the Air

The Writers Festival

Meet the Author

Night Conversation

The Bypass

Good-Bye, Dad

That Burning Feeling

A Friend in Need

Pilgrims’ Progress

Dishing it Out

A Lesson in Arabic

Holy Work

Car Noir

The Bigger Picture

And Then the Police Arrived

What’s in a Name?

Loving One’s Son Just as Nature Made Him—Uncircumcised

Still Small Voices in the Night

Homework

Dutch Treat. Or Not.

Part IV: The Stories That I Don’t Dare Tell (2012–2014)

The Stories That I Don’t Dare Tell

Pride and Prejudice

Splash Back

The Heavens Will Weep

Without Parents

Love Therapist

Bibi Does

Old Man

Quest for Another Homeland

The Court!

Electricity in the Air

Is There a Future?

An Open Letter from the Piece of Shrapnel in the Rear End of an IDF Soldier

A Revolutionary Peace Plan

America

Good-Bye Cigarettes, Hello Yoga

Farewell

INTRODUCTION

It’s been about a year since I left Jerusalem and came to Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, with my wife and three children. We celebrated the anniversary by preparing homemade hummus and frying falafel. By now we know where to buy the right products for making food that approximates the taste of home. My younger son, who arrived here at the age of three without knowing a word of English, asked for another portion of falafel. I sliced a pita in half, stuffed it with a few falafel balls, added a slice of tomato and cucumber, and dampened the contents with some tahini sauce. “Wow, Daddy,” he said after biting into the pita avidly, and added, in English, with a midwestern accent, “This taco is really good.” And I knew I had an idea for my weekly column.

When I started to write a weekly column in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, more than ten years ago, I was still living in Beit Safafa, a Palestinian neighborhood of Jerusalem, with my wife and my firstborn daughter. Since then, I have become the father of two more children; I moved from the eastern to the western part of the city; governments have come and gone; wars have broken out, died down, and erupted anew; and I churned out a column every week.

Writing a weekly column can be a real nightmare. Some days I found myself wandering the streets of Jerusalem and mulling aloud, “What will I write about this week?” If I was apprehensive that I had nothing to write about, or felt that the last column I’d written was not very good, I sank into depression. When I knew I’d written a good piece I was delighted, even if it was about missiles being fired into the country.

Writing the column became a way of life for me. As soon as I sent one column to my editor at the newspaper, I started to think about the next one. I didn’t look for a thought or an idea; I looked for a feeling. The method I adopted was to write about what had moved me most that week. I honed my senses and pursued emotions—fear, pain, hope, desire, anger, happiness. My promise to myself was that I would convey those feelings to the reader by means of personal stories. I tried to be honest and to tell the truth as I perceived it, even though what I wrote was sometimes complete fiction.

During the past decade I’ve written about almost everyone I know. I have very few friends left: people started to keep their distance from me or went silent in my company, for fear that what they said would end up in the paper. I made my wife’s life a misery, and the lives of others in my family, by exploiting them shamelessly if I thought it would help me write a better column.

Mostly, though, I think I tried to survive the reality around me through words, to create order out of the swirling chaos and find an inner logic in what I saw and experienced. The column gave me space to apologize, cry out, be afraid, implore, hate, and love—but above all to look for hope and make my life a little more bearable. That’s why I went on writing it: in the hope that in the end all would be well and that all one has to do is write one’s life as a story—and find a happy ending.

Sayed KashuaJune 2015

NATIVE

PART I

WARNING SIGNS

2006–2007

WARNING SIGNS

April 7, 2006

To: Editor, Haaretz magazine

Re: Sayed Kashua’s column

Dear Sir,

Well now. This is of course not the first time I’ve had occasion to send a letter to the editor of a newspaper on which my husband, who goes by the name Sayed Kashua, is employed. And like the letters that came before, this one, too, is a formal warning. If my demands are not met, I will have no choice but to resort to legal measures.

Your correspondent, my husband, is a chronic liar, gossip, and cheat who unfortunately makes a living by distorting the truth and creating a highly unreliable picture of reality. I am astounded that a newspaper that is considered respectable, like Haaretz, goes ahead and publishes my husband’s abusive articles without bothering to check the accuracy of the material. How can you not have a system, even minimal, that checks whether the columns of your esteemed correspondent might be libelous and constitute grounds for a whole slew of lawsuits?

The law firm I’ve contacted assures me that 90 percent of my husband’s columns that were published in your paper contain grounds for lawsuits whose favorable outcomes are not in doubt. Until now I have avoided filing such suits, as I am not greedy like my husband, your correspondent, who has proved beyond a doubt that he will balk at nothing to make a living. Knowing my husband’s character as well as I do, I am not surprised at his behavior. However, I am amazed that your paper’s many worthy editors are unaware of the gravity of the situation.

As a condition for terminating legal procedures, I demand that your distinguished newspaper publish a crystal clear apology in a place that’s at least as respectable as the one you provide for your immoral correspondent. The paper’s readers need to be aware beyond any doubt that the picture my husband paints of his family life is a crude lie and has no basis in reality.

Almost every week, my husband impertinently, and with your backing, creates a monstrous picture in which I usually play the lead. This abuse has to end, and because there is no way to communicate with the nutcase who has hospitalized himself in my home, I am asking you, who bear exclusive responsibility, to put a stop to this vile smear campaign.

As his readers realize, my husband suffers from a serious addiction problem—by which I do not necessarily mean alcohol and other substances, but an addiction to lies and fabrications that have become an inseparable part of his daily life.

He reached new peaks in his last column, when he described me as an irritable, grumpy woman who wishes him dead and says things like “May worms eat his lungs.” Of course, I never spoke any such words. It’s all the product of the hallucinations and perversions of his feverish mind. Not to mention the other aspersions he casts on me—but this is not the place to repeat them, in order not to offend the public’s sensibilities.

It’s altogether baffling that my husband uses swear words as a regular tool in his writing. The only conclusion is that your editors don’t bat an eyelash at the unbroken string of obscenities.

His descriptions of me cause me no end of grief and trouble. I find myself being forced to provide answers and explanations to my circle of acquaintances, at work, in the neighborhood, and within the family. I am bombarded day and night with questions about groundless accusations that are published in your serious newspaper. As long as I alone was the target of his barbs, I bit my lip and decided to restrain myself in order to keep up an appearance of domestic harmony. Lately, though, my husband has been undermining his children’s routine as well: his daughter and firstborn child is also having to come up with answers and explanations to the parents of the other children in her kindergarten. Last Purim, tears welled up in my eyes when one of the mothers wanted to know—based on material published in your paper—whether my mother, whom your correspondent calls “my mother-in-law,” is really a witch whose only goal in life is to get me away from my husband.

I don’t understand why family matters, irrespective of whether they are reliable, have to be published in newspapers, still less in a newspaper like Haaretz. By the way, I want to take this opportunity to inform you that I am joining the list of those who are canceling their subscription to your paper, and I call on everyone with common sense to follow my example and that of many others who do not allow this defective product into their home.

I am not one of those people who like to go public with family disputes, but in this case, and in the light of past experience, I am well aware that this is the only way to stop the malicious smear campaign. It is my fervent hope that you will follow the path of previous newspapers that received formal warnings and acceded to my request to fire my husband instantly.

The reading public needs to know that my husband—and I am speaking here as a professional with many years of work experience in a psychiatric hospital—is afflicted with any number of personality disorders. In jargon, his condition is officially described as a borderline personality who suffers from a number of behavioral disorders, of which the most serious, perhaps, are paranoid personality disorder, induced delusional disorder, and severe narcissistic damage. The reading public needs to know that my husband suffers from recurrent attacks of delusions—graded as level 4 on a scale of 5—which are becoming increasingly grimmer as he grows older.

Here’s one small example out of many, just to illustrate what I mean. Recently, my husband has convinced himself that he is an Ashkenazi of Polish descent whose parents—both of whom are in fact still alive and living in the village of Tira—are Holocaust survivors who came to this country on an illegal immigrant ship in 1945. Esteemed editors and readers, my husband, your correspondent, has been wandering the streets of Beit Safafa, the Palestinian neighborhood of Jerusalem where we live, telling passersby that he’s the only Ashkenazi in the neighborhood. He gives his address, when requested, as “Beit Safafa Heights.”

I very much regret having been dragged into this series of verbal abuses in the pages of the newspaper. It is unnatural, but in view of the deteriorating situation I am left with no choice. I ask the readers’ pardon.

Yours sincerely,

Sayed Kashua’s wife

P.S. Please publish my letter anonymously.

HIGH TECH

June 1, 2006

“So, what are you going to do today?” my wife asked when I woke up.

“What do you mean?” I replied, not getting her drift. “Go to work, as usual.”

“Don’t tell me you forgot.”

“What?”

“I don’t believe it. For the past week I’ve been telling you that there’s a holiday in the kindergarten today. You never listen. Do you know how many times I told you?”

“What holiday is that?”

“I don’t know, the school’s announcement says Aliyah Day.”

They’re overdoing it in school, I thought. Bilingual, all right, ‘ala rasi, my choice, respect all the religions, the two languages, the two narratives of the two peoples. I respect all that, despite the endless holidays in the school. But Aliyah Day, rabak, for heaven’s sake?

“Who celebrates Aliyah Day?” I shouted. “What kind of cynicism is it to celebrate Jewish immigration?”

“Daddy,” my daughter cut in, “the kindergarten teacher said it’s the day when Jesus went up to heaven.”

“Ah, yes?” I calmed down. “Well, we have to respect that.”

Fine. It’s been a while since I spent quality time with my daughter, and Ascension Day can be a terrific opportunity for bridge building. “We’ll have a fun day,” I said to my daughter. “We’ll celebrate the ascension right.”

So I could have the car, we all left together: first we dropped off the baby at his crèche, which thank God is not bi-anything and follows the Muslim calendar for holidays, and then we took Mom to work.

“Are you hungry?” I asked my daughter when we were alone in the car, and drove to the restaurant in the Botanical Garden on the Hebrew University’s campus. “You see?” I explained to my daughter, brimming with pride at the education I was giving her as we attacked a salad and cheeses. “This garden is filled with flowers, trees, and plants from the whole world.”

“I want to walk around in the garden. Can we, Daddy?”

“Uh,” I said. The thought of a hike wasn’t especially appealing. “Isn’t what you can see from here enough? Look, there are ducks in the pond.”

“No, Daddy, let’s walk a little.”

“All right, finish eating.”

After five minutes of walking, I was cursing myself for the dumb idea of eating in the Botanical Garden. “And what’s this, Daddy?” my daughter asked, stopping next to every explanatory sign.

“Aren’t you tired?” I asked her.

“No, this is really fun. Look at this, Daddy, so pretty and yellow. What does it say?”

“Maybe we’ll go to the mall? I’ll buy you ice cream.”

“Yummy, ice cream.”

I drove to the mall. There’s actually something I have to buy, maybe at long last I’ll change the fluorescent lamp in the bathroom. It hasn’t been working for a year, and I moved the reading light there.

“Daddy,” my daughter said as we waited in the line of cars that were queued for the security check, “can I speak Arabic now?”

“What do you mean?”—I turned around to her—“Of course. You can speak Arabic whenever you want and wherever you want. What are you talking about, anyway?”

The security guard looked through the window and I smiled at him. “What’s happening? Everything all right?” he asked, so he could check my accent. Before I could say, “Good, thanks”—two words without the telltale letters “p” and “r”—my daughter chimed in with “Alhamdulillah”—everything’s fine.

“ID card, please,” the security guard said.

“You hear, sweetie,” I explained to my daughter as we entered a do-it-yourself store, “it’s fine to speak Arabic everywhere, anytime you want, but not at the entrance to a mall, okay, sweetie?”

I bought a fluorescent lamp, a wastebasket for my office, and a shoe rack. “We’ll surprise Mommy,” I said to my daughter, who was thrilled by the shoe rack. She knows as well as I that Mom has wanted a shoe rack since she was born. I received a large carton. The salesman said that assembling it was not a problem. You don’t need any equipment, he added, except a Phillips screwdriver. I hope I have one on my penknife, I thought, because that’s the only tool I have in the house.

Excuse my French, but kus shel ha’ima of the do-it-yourself store and the same to that salesman’s mother. They’re sons of bitches and so is their shoe rack. Who needs a shoe rack, anyway? A million years we got along without it, so what for? I’ll show my wife what for. Two hours I’ve been fighting my Swiss Army knife and their crappy screws, totally baffled by the instructions page, it’s all coming out ass-backward, I’m sweating like a mule, and my fingers are blistered. “Very simple assembly,” ‘alek, you believe it. My back has seized up and I’m broiling with irritation.

I try to remember that my daughter is next to me and not swear too much. And they have the nerve to take money for it. I’ll sue them, the shits. And this Ascension Day, too, where did they dredge that up?

Okay, I have to relax, start from the beginning. There’s still three hours to go before I pick up my wife from work. Inhale deeply, one step at a time. I spread a newspaper on the floor and on it put the different-size screws, the nails, and the pieces of plastic, according to the instructions, according to the numbers.

Perspiration drips from my nose straight onto the forehead of Olmert addressing congress. I actually saw him on TV—it was on all the news channels, live, emotional—extending a hand to peace, and all the Americans giving him a standing ovation. So what if at the same time he killed four Arabs in Ramallah? But what do I care about Olmert now? Shoe rack; three hours.

That’s the good thing about the Jews, that’s what I like about them—promises. They’re good talkers. “Half an hour to assemble it, of course it’s not complicated?”

At 3 P.M. I drove with my daughter to pick up my wife. “Well, how was it, fun?” she asked. I said nothing.

“Daddy got you a surprise.”

“Really? What?”

“It’s a secret,” my daughter said.

At home the shoe rack was fully assembled: handsome, cognac colored, standing in the correct corner. The carpenter cost me 100 shekels for a quarter of an hour.

“Did you do it?” my wife asked. I nodded my head affirmatively. She gave me a kiss.

“But, Daddy,” my daughter said, “you said it’s wrong to . . .”

I lifted her up in the air to make her stop talking, and whispered in her ear, “Today it’s allowed, today is Aliyah Day.”

HEAD START

July 7, 2006

The telephone jangles me out of sleep. My head is pounding and I almost trip and fall when I get up to answer.

“Are you still sleeping?”

“No, I’m working,” I reply to my wife. “Is anything wrong?”

“No. I just wanted to tell you that the battery in my cell is dead, so don’t be alarmed if I don’t answer.”

Wow, what a headache. What time is it, anyway? I check the wall clock: 10 A.M. What day is it? Sunday. Yes, Sunday. What did I do last night? I try to do a mental replay, to make sure, like after every evening of drinking, that I didn’t do anything really bad. It seems to me that I did do something, based on what I manage to remember.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: