12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

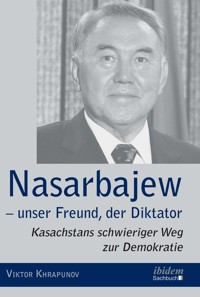

"Like David, I am battling against a Goliath that has almost immeasurable means and powerful allies. I don´t think I can win, I just want to be heard. No dictatorship lasts forever, and if my contribution can sooner or later bring about its downfall, then I will have achieved what I set out to do." The man waging this unequal war is Viktor Khrapunov. He used to be mayor of Almaty, Kazakhstan´s largest city, and the country´s Energy Minister before he was forced into exile. From Switzerland, where he now lives with his family, he brings charges against the rule of Nursultan Nazarbayev, which will soon reach its twenty-fifth year. Nazarbayev, initially welcomed as a young, dynamic president, has become a reckless and unpredictable dictator over the years. From the abusive privatization of the country´s mineral resources and thriving corruption to personal intrigues and the stone-cold elimination of political opponents—Khrapunov´s account of the criminal wheeling and dealing of this self-styled ´ruler of the nation´ tells it how it is. Based on Khrapunov´s insider knowledge from the hallways of global power, his story is also a revelation of Western apathy towards a brutal dictatorial regime. This gripping autobiographical narrative helps the reader understand how Kazakhstan has developed politically from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the modern day, and how it can blossom into a democratic state.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

I write to you far from my homeland

A childhood in Kazakhstan

My years of education

In the Ministry of Energy

Developing Almaty

Years of farewell to Kazakhstan

In exile

What does the future of Kazakhstan look like?

Annex A number of reflections on the future of Kazakhstan

Copyright

I write to you far from my homeland

Just a few years ago, I was a high official in Kazakhstan. Now I'm under threat from the very government I served for so long and have to live in exile.

I sacrificed my whole life working for my country, although I was increasingly disappointed by the drifting of our President Nursultan Nazarbayev into autocracy and by the greed of his family, who little by little took Kazakhstan’s riches for themselves. As a specialist in energy issues and a skilled manager, I hoped to be able to use the strength of my office to block the institutionalized plundering and make life at least a little easier for the people. I was so naive that I even had aspirations of becoming prime minister and cleaning out the muck in the Augean stables which house the highest ranks of Kazakh state leadership. But after several disturbing incidents, in particular after the murder of two well-known people who dared to criticize the regime, I finally started to open my eyes.

Nursultan Nazarbayev guessed this. Within a few years, I had become a disruptive element. The marriage of my son to the daughter of the oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov, who had fallen from grace and been declared a criminal, made the situation even worse. In 2007 I had to resign from my official roles, leave Kazakhstan and move to Switzerland. When the President found out that I was neither planning on returning nor intending to get down on my knees and beg him for forgiveness, the persecution of me, my wife Leila, our parents and our children and even more distant members of our family started. The Kazakhstan’s Prosecutor General brought around twenty indictments against us, each more absurd than the next, and made us out in the press to be a gang of organized criminals.

Since my arrival in Switzerland, my family and I have been undergoing a psychological ordeal. I want to make one thing clear: I was never a politician. All of my roles—as Mayor of Almaty, as Energy Minister and later as Minister of Emergency Situations—were those of a high official working to benefit his fellow citizens. The fact that I was suddenly indicted as a criminal several years after my supposed offences is an insult to my dignity and is an attempt to drag my name through the mud and obliterate my actions from the history of my country.

What is there to be done in a situation like that? I'm not holding out any hope that I will be able to defend myself properly before a court: there is no independent justice system in Kazakhstan. That's why I decided to go on the counter-attack. For almost two decades, I was part of the highest circles of power in the Republic of Kazakhstan. As an eyewitness to the scandalous deeds carried out by this regime, I can reveal the mechanisms which were used to "privatize" the country. I've now been doing this for two years through various interviews that I have given in the international press and through the articles that I publish on my website1.

I also think that it's time for me to report on my tumultuous life, which is closely linked to the recent history of Kazakhstan. This need to defend my honor, and above all to record everything I've done in my life, is pushed me to write this book. I can use this book to bring charges against the "Nazarbayev phenomenon", because, despite the corruption and dictatorship, this man continues to enjoy international respect.

Like David, I am battling against a Goliath that has almost immeasurable means and powerful allies. I don't think I can win; I just want to be heard. No dictatorship lasts for ever, and if my contribution can sooner or later bring about its downfall then I will have achieved what I set out to do.

11.http://www.viktor-khrapunov.com/en/

A childhood in Kazakhstan

How can I explain my deep connection to my homeland of Kazakhstan when I am actually ethnically Russian? Maybe simply by saying that this multi-ethnic state with its harsh climate and warm-hearted population is the country in which I was born and raised and which I only left for the first time when as an adult.

My family has lived in Kazakhstan for generations. My ancestors on my mother's side settled here at the start of the 20th century, driven to Kazakhstan by the Stolypin agrarian reforms, which enabled the allocation of small plots of land to farmers who wanted to settle in Siberia and other peripheral areas of the kingdom. My grandfather on my father's side, on the other hand, was a count who had owned an estate near Perm in the Ural Mountains and fled to China after the Bolshevik Revolution while his family, decimated by typhoid, were stuck in East Kazakhstan. His wife and his five children heard nothing more from him after the day he fled. Nobody knew how he was or whether something had happened to him. Decades later, my father hoped in vain that one day my grandfather would come back to Kazakhstan. My father, the youngest of the five children, lived with his mother until she died and then went to the Front. He first fought in Finland, in 1940, and later against the Nazis. In 1943, he was severely injured in the Battle of Stalingrad when he as the machine gunner covered his unit as it retreated. He returned home a war hero, and shortly afterwards met his future wife, my mother. She was a 17-year-old orphan whose father had been shot during Stalin's purges because he had served in the tsar's army.

I was one of seven siblings, and life was hard for our parents, both of whom had very modest employment. My father worked as an accountant and was Head of the Control Commission of the Communist Party in the Glubokovski District in East Kazakhstan; my mother was a secretary at the Zagotskot, a government body that managed livestock. In 1951, when I was three years old, my father was arrested for being part of a political circle. In his book Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman writes "those who have been at war dreamed of a free country, but they quickly collided with Stalin's power apparatus which forbade any intellectual activity that could not be controlled by the party." My father was condemned to twelve years in a labor camp in a grim trial which is still deeply burned into my young memory. I can still remember how my parents were saying goodbye once the ruling had been pronounced. My father was taken away by the guards immediately and my mother was pulled into a side room. I was left behind in the empty hearing room in front of the three chairs with the high backrests on which the judges had sat shortly beforehand.

My mother raised us alone. Because she often had to work late—Stalin was a night owl and all of the officials had to do as he did—we were left to our own devices. One day, when I was four, my eight-year-old brother, my six-year-old sister, and I set light to a newspaper for fun. The flames jumped over to the mattress lying on the floor. The smoke almost choked us and it seemed as if there was no escape because my mother had locked the door when she went to work. My brother tried to drag the burning mattress into another room and got badly burned. Fortunately, our neighbors rang the fire brigade in time: when they arrived all three of us had already lost consciousness. The doctors had to amputate my brother's right arm.

When Stalin died in 1953, everything changed. Several hundred thousand prisoners were released from the camps and rehabilitated. My father returned home, but refused to rejoin the party and take up office again. "The party didn't protect me when I needed it to", he told the officials who wanted him to return. From that day forward he never again said anything else about the party, either positive or negative.

I am lucky to have been born into an inclusive, loving family. My parents were very well educated and had a high level of moral integrity, so were unable to understand injustice. They raised us with correspondingly high values. We received unending respect from them and always spoke to them using the polite form. I could never have used the informal form of address to my father! We lived very harmoniously with no tension whatsoever. If there were any problems, we talked about them and came up with an amicable solution in a peaceful manner. Since the family was large and everyday life was hard, everybody did their bit. In summer, my eldest brother worked as an educator in a pioneers' camp, and the other children had little temporary jobs too. We lived on the land and owned chickens and pigs, and we grew potatoes and vegetables for us to eat in a vegetable garden. At that time, almost nobody had enough money to buy books, but our father had a subscription to the monthly magazine Roman-Gazeta, in which novels were published in series form. In the evenings, he read to us from the magazine, and afterwards we discussed what he had read. I was able to read by the time I was five, and was registered with the district library. I was probably their youngest user. As soon I was able, I put together my own library: Dumas, London, Tolstoy, Soviet authors—basically everything I could find. Unfortunately the libraries in the province were very poorly stocked.

After returning from the concentration camp, my father accepted the role of chief accountant and controller at the officer where my mother had worked at the state livestock procurement office (Zagotskot). By this point, she was working at the local river port. My father often took me with him on his missions. It is then that I discovered the Kazakh people and their exceptional hospitality. My father had an excellent grasp of the language and traditions of the country. Perhaps that was why we were welcomed with open arms everywhere we went. The Kazakh livestock farmers were still living a very traditional life: large patriarchal families, absolute respect of the elderly, traditional, moderate Islam. Kazakh women were respectful of their husbands and families, but were much more emancipated than the women in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, or Tajikistan. Unlike the latter—and I am referring here to elderly women in particular—they did not wear a hijab. Later, when the Zagotskot was dissolved, my father found a job in a butter factory, where he worked until he retired. Unfortunately he wasn't really able to enjoy his retirement—he died when he was just 66. The injuries he sustained in the war and the prison term had ruined his health.

Although I'm mentioning it here, I by no means want to complain about it. One grandfather who emigrated, another who was shot, a father in prison during the purges—is there anything more usual and banal in the tragic history of the Soviet people? I can count myself lucky that neither my grandmother nor my mother was arrested as a "wife of an enemy of the people" like the tens of thousands of other women, and that as children we weren't stuck in an orphanage or a labor camp for minors. It's also lucky that my father survived a war in which more than 20 million people died.

The tragic history of the Kazakhs

The revelations of Stalin's crimes by Nikita Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union only disclosed some of the thick veil of lies and things which remain unsaid that lay over the history of my country. It took the time of perestroika and the start of the post-Communist era to bring the truth to light. The history of Kazakhstan proved to be particularly tragic, even in comparison to that of the other Soviet republics.

In the 17th century, the Russian Cossacks located in Siberia started to colonize Kazakhstan. At that point, there were nomadic tribes living here who were part of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz ethnicities and formed various different Khanates. For three centuries, the uprisings of the local khans were suppressed, and their winter settlements intentionally destroyed and resettled with Russian farmers, including my grandparents on my mother's side. Between 1906 and 1912 alone, 500,000 farming families moved from the central regions in Russia to Kazakhstan, while the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyzs were driven from the fertile land in the steppes.

After the October Revolution, the people of Central Asia hoped that it would be the dawn of a new era and they would be free from the yoke of colonial masters. But the autonomy inspired by the Mensheviks and proclaimed by the local people was annihilated by the Red Army, and its leaders were shot in the early 1920s. Thus began a new chapter in the somber history of this region. During the 1920s and up to around 1935, Stalin reorganized the territory several times to create the Central Asian Republics. He established artificial borders to prevent the founding of monoethnic republics—history would later show that in reality this mix of peoples who were hostile to one another was a real ticking time bomb. Kazakhstan was founded as a Federal Republic in 1936, and the borders were narrowed around 30 years later by the temperamental Khrushchev. With one hand he gave Russian Crimea to Ukraine, and with the other he gave part of the territory of Kazakhstan to the Russian Federation and two further regions to Uzbekistan.

Under the recent presidency of Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine was able to draw the attention of the entire world to the crime of Holodomor, the artificial famine triggered by Stalin in 1932 and 1933 with the aim of breaking Ukrainian farmers’ resistance to forced collectivization. Only relatively few people are aware that a similar procedure was used against the Kazakh population, which had already been decimated by the terrible famine of 1919-1022 that claimed almost a million victims. Since it was impossible to create kolkhozy [collective farms] with nomadic tribes and their wandering herds, the Soviet government forced them to lead a settled life. This abrupt change in livestock farming lead to a massive outbreak of an epizootic disease in the animals, the meat from which was the main source of food for these livestock farmers. Within a year and a half, around 1.5 million Kazakhs had starved and several hundred thousand had fled to China. According to the census carried out in 1939, there were just 3.1 million Kazakhs left in the country.

Stalin tried to dilute the population even further by sending millions of exiles to Kazakhstan. The Kazakh steppes that make up almost half of the territory have a harsh, continental climate. In winter, temperatures can drop to 50 degrees below zero centigrade (58 degrees below zero Fahrenheit), and in summer they can hit 50 degrees centigrade (122 degrees Fahrenheit). It is here that between 1936 and 1944 entire peoples who were deemed to be "dangerous" or "treacherous" were deported on the orders of Stalin: Poles, Koreans, Volga Germans, Greeks, several Caucasian people including Chechens and Ingush people and Crimean Tatars. They were left to their fate in zones which were under surveillance and forced to build their houses themselves and farm almost entirely infertile land to survive. Half of them died. At the same time, millions of prisoners were brought to Kazakhstan from the camps in Siberia which were too full. The sinister names of ALJIR1, Karlag and Steplag, these offshoots of the gulag, were immortalized by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his novel TheGulag Archipelago. In this way, Kazakhstan became a sad rendezvous for peoples who had been exiled and oppressed by Stalin.

Another stage of the colonization of Kazakhstan is associated with the name Nikita Khrushchev. Since the agriculture practiced in the kolkhozy was not particularly productive, from 1954 Khrushchev decided to clear several million hectares of uncultivated land in the Kazakh steppes to improve the wheat harvest and reduce the amount of cereals purchased from abroad. The clearing was declared the "building site of the Komsomol"2 and millions of young people, almost all from the three Slavic republics of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, were dispatched to carry out construction and agricultural work. The students often only came for two or three months in the summer holidays, but almost a million Slavs were seduced by the high salaries and ultimately settled in Kazakhstan. In 1959, just 50% of the 9.3 million inhabitants of the country were ethnic Kazakhs.

The language policy also discriminated against the Kazakhs. Although literacy among the population was massively promoted after the end of the civil war, in 1929 the Latin alphabet was chosen over the traditional Arabic alphabet, and this in turn was replaced by Cyrillic script in 1940. This meant that Kazakhs were unable to read either their own classical literature or that of the other Turkic peoples, let alone the Qur'an. Over time, the heavily diluted Kazakh people lost their national identity and their language. By 1957, there was only one school left in the capital of Alma-Ata where lessons were carried out in Kazakh, and across the country there was just a single higher education institution, which taught primary school teachers who were going to work in rural areas.

The curse of the military and industrial complex

The insidious Soviet colonization which was carried out under the guise of "friendship among peoples" can primarily be explained by the extraordinary mineral resources in Kazakhstan. Gas and petroleum, uranium and zinc, titanium and chromium, gold and copper, silver and molybdenum ... practically all of the elements in the periodic table can be found in Kazakhstan. The major industrialization of the country in the 1930s received a boost during the Second World War when hundreds of important factories in the European part of the USSR, partially occupied by the Germans, were evacuated to Kazakhstan. Cities and workers' estates, factories and mines, roads and bridges were all built using a workforce of half a million refugees and deportees who worked like slaves. Within just a few decades, my country had turned into a kind of branch office which supplied the entire gigantic Soviet military and industrial complex with raw materials.

Stalin decided to create the Semipalatinsk3 nuclear weapons test site (18,000 km² (6,950 square miles)) to the south of the Irtysh River. This is where the tests on the first Soviet atomic bombs were carried out in 1949, and in 1953 on the first thermonuclear bomb. The entire region was seriously contaminated, as strength of the nuclear charges which exploded below the ground and in the air between 1949 and 1953 exceeded those at Hiroshima by 2,500 times. The health consequences of these explosions were never officially recognized, although hundreds of thousands of people in Kazakhstan developed cancer and malformations in newborns have become the norm. The harm caused to the genetic heritage of the local population is likely to last for several centuries more.

The Soviet military and industrial complex used the strategic location of the Kazakh steppes and set up additional important military facilities there. The military facility in Baikonur, which was originally to be used for tests with ballistic missiles, particularly intercontinental missiles, became the first cosmodrome in the world. Several military bases and airports were built in the country, and the secret city of Stepnogorsk, which did not appear on any geographical maps, housed two combines where enriched uranium and biological weapons were manufactured. Between 1942 and 1992, in other words for almost 50 years, secret tests with biological weapons which had been forbidden by international agreements were carried out on Renaissance Island (oh the irony!) on the Aral Sea.

This uninhibited militarization caused immeasurable ecological damage. In order to provide the Soviet army with intercontinental ballistic missiles, Moscow ordered a drastic increase in the production of cotton since cotton is an important component of rocket fuel. This could only be achieved by means of intensive irrigation of the fields in the south of Kazakhstan and in Uzbekistan, where cotton became a monoculture, to the detriment of the vital interests of the two countries. Almost all of the water in the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, which flowed into the Aral Sea, was diverted to enable irrigation. Within around 20 years, the majority of this inland sea, once one of the largest lakes in the world, became a desert-like landscape, and the entire region around the dried-out sea was destroyed. It was not just the shipping and fishing that disappeared. Pesticides and other toxic substances had collected at the bottom of the lake and now became dust. Sandstorms spread these toxic substances hundreds of miles around the lake. Renaissance Island has now joined up with the mainland, and nobody knows whether the rodents in the region will one day be infected by pathogens which cause severe diseases, such as anthrax, the plague, Malta fever or botulinum toxin, all of which are found in the soil. It's an absolutely catastrophic scenario. Regardless of whether it is possible to prevent a disaster like this, one thing is certain: the climate in the region has become more continental, many species of plants and animals have died out and the population is suffering from both unemployment and massive health problems. These include the aforementioned malformations in newborns and a high level of child mortality. Around ten years ago, our national writer Abdizhamil Nurpeisov dedicated an enthralling novel entitled There was a Day and there was a Night to this subject.

1.Camp at Akmolinsk for the wives of "traitors to the Fatherland"

23.Soviet Communist Youth

34."Semeï" in Kazakh.

My years of education

But I only found out about all of that much later. As a teenager, I had no idea about my country's past or the state of its natural resources. In 1964, I was 16 years old and had come to the end of compulsory schooling. My family decided to send me to a technical grammar school so that I would learn a profession as quickly as possible, without going to the comprehensive school. I chose the industrial school in Ust-Kamenogorsk and passed the entrance exam with flying colors. I wanted to study the automation of production lines, and really enjoyed studying. But six months before completing my education, an incident changed the course of my youth.

It was December 31st, 1967. I was celebrating New Year's Eve with my friends in a hall of residence. We wanted to preserve the memory of the evening, so we knocked on a neighbor’s door and asked to borrow his camera. But he refused and insulted me. I got angry and hit him. Since I boxed on a regular basis, it wasn't just a harmless skirmish. The man complained to the school authorities. The Director decided that I wasn't to be excluded as I was a very good student, but he revoked the exemption from military service which was granted to students. That meant I had to serve in the army for two years before I would be able to continue my education.

I was called up on January 5th, 1968. My parents were furious. I remember that my father bought a bottle of wine before I left and we drank together for the first time. I initially trained in Irkutsk, then I went to Krasnoyarsk and was later deployed in the Tomsk region with the strategic missile troops. Here I served in a secret unit in the middle of the Taiga surrounded by a barbed wire fence. That winter was the coldest of the century, and the temperatures dropped to 52 degrees below zero centigrade (62 degrees below zero Fahrenheit). We cut masks out of old coats to cover our faces. I'll never forget the first night I kept watch. It was pitch black, the snow crunched underfoot, and at one point a birch tree cracked suddenly and loudly and broke into two because of the frost. At that time all of the young people were crazy about spy novels, and I was no exception. At first I pictured myself in the stories, always scanning the surroundings to see whether there was a spy hiding behind a tree who had decided to penetrate our base.

The following episode clearly illustrates the degree of our indoctrination at that point. There was a territorial conflict going on between the USSR and China over the island of Domanski1 on the Ussuri River on the border between Russia and China. In our unit, there was one soldier who had lost an arm in the battle for Domanski, a "hero" who told us all about his adventure. Entirely unexpectedly, one day we had to line up and our commanding officer said: "any volunteers for deployment to Domanski take one step forwards!" Without a word, all of the soldiers took one step forwards. I was 18 years old and willing to fight the Chinese and even die for this piece of land that was less than half a square mile! Fortunately they were only testing our fighting spirit, as we were part of a special unit and were indispensable to the protection of a top secret complex, the closed town of Tomsk-7, 12 km away from Tomsk, where combines that produced both enriched uranium and military-grade plutonium and missile defense systems were housed. This town and its combines, built in the 1930s by prisoners in the gulags, still exist to this day. The town is called Seversk.

On arrival in the regiment, I had to complete the usual initiations, but my boxing experience meant I was quickly able to earn respect. But my impulsive nature got the better of me again. There was a difference of opinion during a volleyball game, and a sergeant on the opposing team called me an idiot. I asked him to apologize. He refused, so I hit him in the face. He collapsed and had to be taken to hospital. I had breached army regulations—no soldier is allowed to hit a senior officer under any circumstances. For that action, I risked being sentenced to a further three years in a disciplinary battalion. Fortunately, the commanding officer of the regiment decided not to bring the case before the military court, as the sergeant in question was known for his brutality. But I had learned my lesson, and from that moment onwards I kept my emotions under control.

When I returned home in 1969, I completed my studies at the technical grammar school and received a very good grade. As a reward, I was sent to Almaty to work in the thermoelectric power station which had been built there in 1935. Alongside my job (I started as an automatic systems mechanic and then became a foreman), I enrolled in the distance learning university. In 1977, I received my diploma with a grade of "very good", and as a result I was quickly promoted to head of the turbine workshop. Like everywhere in the facility, the equipment there was outdated, but all of the staff worked really hard. The management imposed harsh working conditions on us and pushed us our very limits.

These professional successes, however, were not the slightest bit of use to me when it came to solving my biggest problem: my living arrangements. On arrival in Almaty, I was given accommodation in a workers' residence, where I had set up home with my wife, who I had met at the technical grammar school. Even the birth of our two daughters in 1971 and 1975 did nothing to change our situation. We had a single room in a residence for couples in which dozens of families shared the sanitary facilities and one communal kitchen.

The story of how I got an apartment is a particularly good illustration of the general state of the industry and the infrastructure at the end of the Soviet Era. On the night of the 4th into the 5th of February 1984, the large boiling water pipe in my workshop exploded. I came running; an ambulance was already there. Somebody had been badly burned. I put some boots on immediately and fought my way into the workshop. For four hours I desperately tried to mend the leak and was rescued in the nick of time. I was taken to hospital at dawn in a terrible condition. I was burned from the waist down, and when they took my boots and trousers off the skin came with them.

When I came round, I wasn't given great chances of survival: 43% of the surface of my skin was severely burned. But I was lucky: I was treated by Professor Konstantin Palgov, a well-known traumatologist. After my stay in intensive care, he prescribed six sessions in the "barometric chamber". In this procedure, the patient is placed in a diving suit made of glass, into which oxygen is pumped at high pressure. The oxygen penetrates the tissue, preventing necrosis and promoting healing. The first five sessions were perfectly normal, but during the sixth I had hallucinations. Through my glass cover I saw flames and smoke, and when I was brought back to my room I had an attack of tachycardia and was clinically dead. At that moment, I saw myself from the outside. I was in a tunnel, surrounded by people in grey, semi-transparent clothing. An invisible force then pulled me from this procession of the dead and put me in a peaceful scene: an azure blue river, green meadows, grazing animals. I wanted to talk to the people in white tunics, but they didn't understand me. They prevented me from approaching the table on which lay a person whose head was surrounded by a halo. I suddenly wanted to visit the place were I was born, Prigorodnoye. And in an instant I was there. I saw the village, our house and my family sat around the table. But an inner voice ordered me to go back to the hospital. These visions, which are described in academic literature as near-death experiences, were the most impressive experience of my life, a sort of "flight in the sky".

When I came round, they had already removed part of my heel, which had necrosed. There was a risk that the bone would come under attack next. After the miracle of the near-death experience, however, the healing process started very quickly and was complete nine months later. During this time, another small miracle happened. The accident, which could have cost me my life, achieved something for me that I had been waiting many years for: the Mayor of Almaty ordered that I be given the first apartment that became free.

When I resurrect these memories of the Soviet Era, I am aware of how hard our lives were at the time. But our upbringing had drummed into us pride in our great Fatherland, the USSR, and our Republic of Kazakhstan. I should also say that the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, Dinmukhamed Konayev, was highly regarded. He was appointed in 1964 and managed to double the industrial potential of the country within just a few years, mostly thanks to his personal friendship with Leonid Brezhnev. At that time, the first secretaries were all fighting for the decisions made by the party headquarters to be to the benefit of their respective republics, and they were constantly competing with one another for this. The battle between Konayev and Rashidov, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, was hard fought. It was also about the important issue of which Central Asian city was the most beautiful, Tashkent or Almaty. At the end of the 1960s, Tashkent appeared to have won: the old, traditional buildings which had been made from cob collapsed in the major earthquake in 1966 and the city had to be rebuilt from scratch. As the underground was being opened in Tashkent, Konayev received permission from Brezhnev to build a metro in Almaty too. Later, a very high television tower was built on Kok-Tube Hill in Almaty. Tashkent soon followed suit. The battle for fame and glory stimulated the development of both cities.

The residents of Almaty admired Konayev in particular for modernizing the city. He had created a jewel, the most beautiful city in Kazakhstan. I personally saw Almaty for the first time in 1968 when our unit was returning to Tomsk after carrying out maneuvers on Lake Balkhash. The cattle truck we were traveling in remained on the platforms near Almaty for a long time, and I was enchanted by the view of this city, which climbed high up the slopes at the foot of the Trans-Ili Alatau massif. It was the end of July, and the apple trees were covered with giant fruits. When the carriage continued that night, I held on to the window hatch and was fascinated by the gigantic beam of light that this city formed with its sparkling lights against the background of the dark mountains. I got to know the city properly two years later when I settled there. I was really impressed by the clear, rectangular network of streets and by the original architecture. I will always carry this love for Almaty with me. An important part of my life is linked to this city. But how was I to know, when I moved here as a simple mechanic, that I would one day be mayor?

Perestroika

My own promotion coincided with Mikhail Gorbachev coming to power. In 1985, after 14 years of impeccable work in the power station (I was named best workshop official in the city), I became chief engineer of the Almaty heating network. This post brought with it a great degree of responsibility, as the heating system in the former Kazakh capital was probably the most complicated in the entire USSR. This was due to the geographical location of the city, which was on four plateaus of different heights, necessitating complex settings in terms of water pressure. Shortly after I was appointed, I tried to convince the authorities that the outdated pipes needed to be changed as soon as possible in order to prevent tragic consequences. Within a year, we had built 13.8 kilometers (8.6 miles) of central pipes to ensure the correct distribution of heat, thereby complying with the regulations. By January 1986, the city was equipped to deal with harsh winters. This is what drew the attention of the city's Party Committee.

I joined the party in the 1970s after years of doubt and hesitation. In school, I had enjoyed higher mathematics and the study of material resistance, but the social sciences lessons in which the teacher drilled it into us that our system was the best I found deadly boring, and I didn't want to join the Young Communist League and attend the dreary meetings. I preferred spending my free time boxing.

So I completed my military service without being a member of the Komsomol, which seemed strange. But an incident in the army ultimately convinced me to join the youth organization. When I was being threatened with the disciplinary battalion because I had hit a sergeant, the zampolit, the person responsible for ideological work in the regiment, promised to get me out of the fix if I joined the Komsomol. He wanted to improve his statistics, because in theory all young people from the age of 15 or 16 had to be members. I had no choice. The zampolit was true to his word and ultimately convinced the commanding officer of the regiment not to take the matter to court.

On August 21st, 1968, we all were instructed to assemble around the loudspeaker which was broadcasting the state radio in a barracks in our base. Our unit comprised almost 350 soldiers and almost as many officers because we were a special military unit. This order at 10 o'clock in the morning was so unusual that it caused panic. I remember the faces of my comrades, who were otherwise happy and prone to mischief, which were suddenly serious and reserved. Everyone had the same thought: had war broken out? At 11 o'clock, the government announced the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. They reported that German tanks were about to infiltrate our brother nation.

Shortly after that, the officer responsible for ideological work—the same zampolit who had convinced me to join the Komsomol—told us that all Czechoslovak villages had also been occupied by Warsaw Pact troops. He turned to a young Kazakh boy who came from a far away village and said "tell me, Private Yumagulov, are the units of ours which have marched into the Czechoslovak villages now occupying forces or not?" The soldier answered "yes, they're occupying forces." The zampolit leapt up. "No they're not! They are internationalists! They are fulfilling their international obligation to ensure that Czechoslovakia remains socialist. This country took part in the revolution, and the working classes around the world, the entire progressive international community, is now obliged to defend the revolution everywhere in the world.

This story made me think. The rumor quickly spread among the soldiers that there was no threat from Germany. Why, I asked myself, should we send troops, put the lives of our young soldiers on the line, shoot at people, kill them? Was this really an international obligation and not merely the policy of a small group of people who used internationalism as a pretext?

That was why I didn't enroll in the local Komsomol cell when I returned to school. I didn't go to the meetings either, even though my attendance would be been recorded in my personal file. However, when I arrived in Almaty after finishing school, I was very impressed by Evgeni Volkov, the Director of the thermoelectric power plant. Alongside his job, he had made a career for himself in the Komsomol and later in the party. This happy, warm-hearted man was a born leader who people enjoyed following. Under his influence, I reconciled myself with the Komsomol. But I didn't stay long: in 1973 the head of the party cell in the power plant called me to him and said "I see that you work well, you're highly qualified and you don't shirk away from unpleasant tasks. You never say no to overtime. I want you to join the Party." The workshop manager also put pressure on me. The Party urgently needed well educated, skilled workers. Finally I agreed.

But back to 1986 and the period of thawing which started under Gorbachev. The Party leadership wanted to get people from industry to join in order to breathe new life into the Party. After the heating system had been renewed, I received an urgent call to come to the Committee of the Almaty region. I hurried there in a jacket that was still wet because I had been in a heater cell carrying out tests when the order came through. The First Secretary of the Committee, Mendybaev, welcomed me like a close relative. He asked a few questions and then said "prepare yourself, you're going to be called to the Central Committee." His prediction was confirmed that afternoon. I was batted around like a ball from one office to another. The officials asked me questions and then I was told: "tomorrow you're going the meet the Second Secretary of the Central Committee of Kazakhstan." The next day I was received by Oleg Miroshkin. He spent an hour asking me for details about my life and my career, then he solemnly declared that he was recommending me for the office of President of the Soviet Executive Committee in the Lenin district, a region of Almaty. In short, he was proposing me for mayor.

On October 21st, 1986, the President of the Executive Committee of the city, Mayor Zamanbek Nurkadilov, signed my interim nomination. A month later, this was confirmed by a vote of the district representatives. I was to hold this position until 1989.

And so began my friendship with Nurkadilov, who was murdered in November 2005 on the orders of Nazarbayev or someone close to him. But we'll come back to that later.

Times of trouble

When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he wanted to draw fresh blood as soon as possible, not only by redesigning the base of the party, but also by replacing some members of the Politburo—bigwigs who had been in office for decades and wanted to hinder his policy of reform. In particular, he wanted to get rid of Konayev, who was close to Brezhnev, had ruled Kazakhstan for 22 years and exerted great influence over the Politburo. In the best of Soviet traditions, Gorbachev asked Nursultan Nazarbayev, then head of government in Kazakhstan, to expose Konayev to public criticism at the 26th Party Congress of Kazakhstan in February 1986, in order to force him to resign.

By that point, Konayev had already lost a lot of his former popularity. Like Brezhnev, he had been in power too long, surrounded himself by courtiers and kept managing to eliminate his competitors. For example, the high dignitary Erkin Auelbekov, who was thought to be a potential successor to Konayev, was sent into "golden exile" in Kyzylorda in 1985. Discontent grew among the elite. People were tired of the fact that there was no competition and that it wasn't possible to work your way up through the ranks unless you belonged to the "club". Offices were passed from father to son, even in the middle levels of the nomenclature. Under the influence of his wife, an ethnic Tatar, Konayev also favored the Tatars to the detriment of the Kazakhs. The atmosphere became more and more suffocating.

Nazarbayev found it difficult to speak ill of Konayev, because he had him to thank for his rapid ascension. In 1977, Nazarbayev, who was only 37 years old, became Secretary of the Communist Party cell in the metal industry combine in the city of Karaganda. At the time, the Karmet combine was the second largest combine in the USSR after the one in Magnitogorsk. On the face of it, Nazarbayev did not have any chance of being promoted quickly, and he was also not very well educated and had no training other than an evening course in the factory, while those occupying higher roles in the nomenclature had generally graduated from a Party high school.

He had some unexpected luck. An influential local journalist called Mikhail Poltoranin2