Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

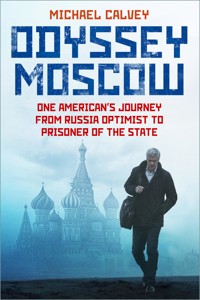

'A riveting tale of betrayal and lawlessness by the Russian Government, told by the most successful US investor in Russia' – Ambassador John Sullivan, US Ambassador to Russia 2020–22 It is dawn on Thursday, 14 February 2019, and armed FSB agents are raiding Michael Calvey's Moscow apartment. He is being arrested for a crime that never happened. Twenty-eight years earlier, Calvey – a newly graduated, aspiring Wall Street hotshot – made a short trip from America to the recently collapsed USSR to look at potential investments. Sensing huge opportunity, he soon based himself in Moscow, where he lived through the 'Wild East' years and went on to build several billion-dollar funds – earning enormous returns for Western investors as Russia opened up to international business. He gained a reputation that would lead to Bloomberg describing him as 'a legend in the Russian market, with a reputed aversion to any kind of foul play'. But now, he finds himself thrown into Moscow's notorious Matrosskaya Tishina prison on charges trumped up by local business rivals. As the White House and Kremlin argue about his incarceration, Calvey is caught in a Kafka-esque trap, denied access to evidence proving his innocence. Odyssey Moscow is the story not just of Michael Calvey, but of how Russia's era of hope and aspiration finally died, and how light can be found in the darkest of places.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For the men of cell 604. Your courage and decency during the darkest of times was, and remains, an inspiration.

Jacket illustrations: Michael Calvey arrives for his hearing, 29 October 2019 (Maxim Shipenkov/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock); Red Square at sunrise (Mordolff/iStockphoto).

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Michael Calvey, 2025

The right of Michael Calvey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 731 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Preface

SECTION 1: February 2019

1 The Accused

2 Welcome to Alcatraz

3 Genesis

4 Cell 604

5 Brothers in Arms

6 Trailblazer

SECTION 2: March 2019

7 No End in Sight

8 The Labyrinth

9 Opportunity and Turbulence

10 Levelling Up

11 The Good Times

12 Man Grows Accustomed to Anything

13 Dark and Light

SECTION 3: 1–12 April 2019

14 The Bad Deal

15 Red Flags

16 Dropped Keys

17 Day of Reckoning

SECTION 4: 13 April 2019–14 January 2022

18 House Arrest

19 Chess

20 The Trial

21 Home

SECTION 5: Aftermath

22 Lessons Learned

Epilogue: Brave New World

Acknowledgements

Preface

Thursday, 14 February 2019. Moscow

It is almost dawn when I hear the dull thudding through my earplugs. I have only recently arrived from London and the noise comes at me through a fog of semi-sleep. Thud. Thud. THUD. On it goes. I assume it is the neighbours. What the hell are they doing at this hour?

I sit up in bed and adjust my earplugs. That’s when I work out that the noise is not coming through the wall. It is too clear and crisp for that. With growing anxiety, I realise it’s coming from my front door. I get out of bed to investigate, wearing just a pair of shorts, but the view through the peephole in my front door is blocked by someone, or something. Then there is a new round of pounding from the other side, shaking the door with its force. I hear the muffled voices of several men directly beyond, standing just a few feet away. Holy shit, they are here for me. Now panicking, I rush to my bedroom to get dressed. Before I can get there, the door bursts open and ten or twelve men charge through, some with weapons drawn, screaming at me to freeze and raise my hands in the air. Shocked and disoriented, my hands shake with adrenaline.

When I went to bed just a few hours ago in my rented apartment in a 1990s block just off Moscow’s central Tverskaya Street, my only concern was to be ready for my meeting later today. There has been an ongoing business dispute and the hope is we can negotiate some sort of resolution. Now I find myself literally staring down the barrel of a gun. A collection of them. The men wielding the firearms, I grasp, are operatives from Russia’s FSB – the successor organisation to the old Soviet secret police, the KGB – and from the Investigative Committee, roughly equivalent to the American Federal Bureau of Investigation.

I grab yesterday’s clothes from the floor – jeans and a button-up shirt – and try to put them on as one of the invaders shouts at me to keep my hands visible. He holds his gun with tension in both hands, pointed at the floor. Dazed, I do up the buttons of my shirt all wrong. When they can see that I am going to try to neither fight nor flee, they holster their weapons but keep their hands on them, just in case. From their muscular frames and abrasive commands, it is clear that these are hardened operativniki trained in combat. Two of them stand either side of me, one holding on to my arm, while the others fan out through the apartment to secure the location. They push me towards the sofa to sit down, while they remain standing.

With the search in full flow, one of the investigators engages with me. He is in his late 30s or early 40s, the only one who has no weapon. He also wears a different uniform from the black or camouflage outfits the others sport. He is passively aggressive and warily confident, rarely making eye contact as he takes in the apartment and considers his next steps. He presents me with a paper indicating the criminal accusations made against me. They relate to the business disagreement I have come here to try to settle. My company, Baring Vostok, includes in its portfolio a bank, the Vostochny Bank. Vostochny recently acquired shares in a group of promising fintech companies in lieu of a debt, but two minority shareholders at Vostochny recently raised questions about the deal. I immediately understand that this search must have been initiated by these shareholders, Artem Avetisyan and Sherzod Yusupov. I know their accusations are bogus and without substance. Yusupov even admitted a few months earlier that he had only raised questions about the deal because of a wider shareholder conflict in which his own actions were being investigated. But negotiations to resolve the dispute have been heated and recently reached an impasse. It was my hope that this evening’s scheduled meeting might help us all find a new path through. A hope that now seems distant, to say the least.

My first impulse as my apartment is ransacked is to try to bring my racing heart rate down. The logical side of my mind dismisses the idea that this is the first step in a genuine criminal investigation, since there has been no crime. It is, I conclude, surely just a business tactic – a brutally delivered message from Avetisyan and Yusupov intended to intimidate me and to sway the flow of negotiations in their favour. I try to remain stoic and keep a poker face. I want to avoid showing any outward sign of the fear gnawing deep in my core.

They search my apartment for about four hours, during which time they confiscate my phone, iPad, and laptop, as well as old personal papers. I have no idea what they hope to find. They even carefully flip through a pile of business cards and very old photos – dating from pre-digital days when we still had film cameras – as if they think they might find some evidence of espionage. Mr Passive-Aggressive pauses at one photo in particular. It’s of my first child, Mishuta, when he was about 4 years old. He has a black eye in the picture, the result of his typical rambunctiousness. The investigator gestures at it and gives me an accusatory look. He asks something like ‘Are you also guilty of child abuse?’ Like all my interactions with them, it is barked at me in Russian. I am so stunned that I can’t tell if the question is a joke. ‘Are you serious?!’ I demand to know. He ultimately decides not to seize that photo and discards it, but he keeps several others for ‘further investigation’ – old family snaps and pictures from a friend’s wedding, presumably to check out if I am in touch with American officials or any Russian opposition figures.

About halfway through the search, an advocate, Dmitry Kletochkin, arrives. I haven’t met Dmitry before but his firm has done some work for Baring Vostok previously, and he has been scrambled on short notice to come and support me during the search. I have been forbidden to use my phone, but it turns out my office is also being raided, so the news has quickly got back to my colleagues and they immediately engaged Dmitry to come to my aid. Having lived in Moscow since the ’90s, I can speak Russian fluently, which is how I have been able to communicate with my interrogators. But Dmitry speaks English. One of the first things he does is to pull me aside for a private word. ‘Imagine that this is like the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor,’ he says. ‘It seems devastating right now, and we are obviously at a disadvantage since we weren’t prepared for it. But there is a system to fight back, and in the end we can win.’ I think that this simile is an apt one. In any event I take comfort from it.

After they finish their search, the lead investigator settles down weightily at my kitchen table to write up a report. As this takes him a couple of hours, the six or seven remaining FSB operatives mostly sprawl out on my sofas and take naps while I pace nervously around my kitchen. Once the report is printed and signed, everyone puts on their warm coats and I am led downstairs past the stunned concierge, a typical 70-year-old Russian grandmother, who still hasn’t recovered from the shock of the morning raid. She watches on as I am stuffed into an unmarked car with a few FSB operatives flanking me closely on both sides. The engine revs up and I am driven away to the headquarters of Russia’s Investigative Committee, a roughly fifteen-storey building set amid mostly Soviet-era residential apartments in the Basmanny district, just outside Moscow’s Garden Ring Road.

In the course of a few surreal, terrifying hours I have morphed from one of the most successful Western businessmen in Russia into a prisoner of the state. Like Odysseus setting off to return to Ithaca after the long Trojan War, I have no idea what now awaits me. Or when I’ll be back home.

SECTION 1

FEBRUARY 2019

1

The Accused

The Russian Investigative Committee headquarters are a cheaply constructed relic of the 1990s. Before we are allowed to enter, we have to pass through a temporary security checkpoint – a tiny, windowless kiosk outside the main entrance. Today the checkpoint is jam-packed with witnesses or detainees like me: about ten people, including a few FSB minders, standing shoulder-to-shoulder in the dim space while paperwork is checked. No one makes eye contact; the tension is palpable, and the suffocating room reeks with sweat. After fifteen or twenty minutes, my documents are approved and I am led inside the investigators’ fortified compound, surrounded by high, concrete walls topped with barbed wire.

The main building is a dreary place, with long corridors of closed, silent offices. It reminds me of Orwell’s Ministry of Truth. There is an atmosphere of plodding but irresistible force, the kind that can slowly grind a stone into powder. It’s the sort of place that instils not exactly fear, but hopelessness.

By the time our arrival is ‘processed’, it is about 2 or 3 p.m. I am left with my advocates (Dmitry has now been joined by a colleague) in the office of a major – the same investigator who has led the search of my apartment – while he goes for a long lunch. It is a small, typically cluttered office of a mid-level bureaucrat, with dusty wooden filing cabinets stuffed with towering stacks of official papers, accented with random personal knick-knacks including, incongruously, miniature gnomes and tiny mammoth tusks.

I learn from Dmitry that the investigators have been busy this morning. Several of my Baring Vostok colleagues – Vagan Abgaryan, Philippe Delpal and Ivan Zyuzin – have also endured house searches, as have Maxim Vladimirov, the CEO of PKB (another company involved in the dispute), and Alexey Kordichev, the former CEO of Vostochny. They are now all being questioned elsewhere in this same Investigative Committee building.

I am told that, when the major returns, I will be interrogated and a formal statement taken. My advocates remind me of some facts around the business deal in question, which is helpful as it all happened a couple of years ago and I don’t have access to any files. The major appears and I give my statement, explaining that I wasn’t involved personally in the deal since our funds had no relationship with IFTG, the company at its centre, but that I knew that it was profitable for Vostochny. I also lay out how our accuser, Sherzod Yusupov, had himself personally negotiated the transaction and approved it. I name two or three people and companies who I am sure have all of the relevant documentation and can prove that no crime was committed. We are allowed to check the statement for mistakes before it is printed and signed by all sides. By now, it is about 7 p.m.

In a rare gesture of humanity, I am allowed to make a single phone call using my advocate’s mobile phone. I call my wife, Julia, who is back at home in the UK, where we have lived for the last ten years. She answers hesitatingly, no doubt nervous of a call from a phone number she doesn’t recognise. I can tell immediately from her voice that she already knows what is going on. She must have been under incredible strain today, but she is an unbelievably strong woman – truly the foundation stone of my life. We both almost lose it during the call but when I start to cry, she quickly regains her composure. She tells me exactly what I need to hear: that our family depends on me staying strong. It is tough love at its best, sobering and true. We discuss how to explain what is happening to our three kids and agree to wait to see what tomorrow brings – it is still unclear whether we are being subjected to a savage negotiating tactic or whether they actually intend to charge and convict us. I tell her, of course, that she shouldn’t come to Moscow, even though she wants to support me. I feel much stronger knowing that she and the kids are safe and out of reach of our enemies.

I have another couple of hours to wait before I am sent to an overnight detention centre. While I wait, a new investigator approaches me: a young man in his mid-30s dressed in a fashionable three-piece suit. Unlike the other officials I have met so far, he speaks very good English. Catching me in the corridor by the elevators, he asks how I am doing in these difficult circumstances. The question strikes me as odd and I suspect this is no chance encounter; he seems to be fishing for information. We have a brief and light conversation about some of the differences between America and Russia. He asks me, ‘How much salary do American police investigators earn?’ This is typical of the sort of question I often get in Russia, but I still find it ironic to hear in the corridors of Russia’s Investigative Committee. I know what he is angling at, trying to show that his salary is a pittance compared to Americans in the same job. I tell him I don’t know the figures, since I have never been directly in contact with America’s criminal justice system, but I lowball a guess at $3,000 per month. He looks at me suspiciously, saying, ‘Well, if that’s all they get as salary, they probably get a lot of other benefits for free, like housing.’ I realise there is no point trying to debate the subject as he clearly only wants his own prejudices confirmed. So, instead I simply change the subject.

Before long, I am put into handcuffs on the orders of the major, loaded into a cage in the back of a convoy truck and driven around Moscow for what seems like several hours, stopping occasionally to drop off or pick up other detainees. The cage, which I have to myself, is dark and it is impossible to see anyone else, though I can hear noises of at least three or four other prisoners locked in their own spaces. A wave of exhaustion from the stress of the day’s events sweeps over me, so I try to close my eyes and rest, but it’s impossible to find a comfortable position as the truck lurches and stops and starts abruptly, again and again. It is overheated too, as is often the case in Russian vehicles, so I swelter in my winter down jacket that I can’t remove because of my handcuffs. Whenever someone is dropped off or picked up, the door opens for a few minutes, ushering in a swoosh of freezing Moscow air, initially refreshing but quickly leaving me shivering. Veering between sweltering and freezing for hours on end feels like another intentional punishment.

Finally, the truck stops and it is my turn to be led outside. We have arrived at a temporary detention centre for those awaiting trial. There are apparently several such facilities in Moscow, each about three or four storeys high and with space for between fifty and seventy-five cells. I have no watch and my sense of time is off, but I gather it is well after midnight. I am ordered to take off my clothes and I’m searched from head to toe. They confiscate anything that might be either useful to me (like a pen and paper) or dangerous (my shoelaces and belt). When I have redressed, they lead me to a small cell, no more than 3m by 4m and containing three beds. Apart from that, there is one small shelf, an ancient metal teapot for boiling water, a sink, and a toilet area in the corner – in fact, just a filthy hole in the floor with a metre-high cardboard screen on two sides.

There are already two prisoners in the cell. I am initially apprehensive about how they’ll receive me but I don’t have to worry for long. One of them, Sasha, a barrel-chested Russian bear about 40 years old, immediately introduces himself. The other, Ildar, is a short, wiry Chechen in his early 20s. He is more reticent, not moving from his bed and only nodding vaguely to acknowledge me. When I tell them my name, Sasha asks where I am from. ‘No way!’ he says when I tell him. ‘A real American? That’s amazing!’ They ask how I have ended up here. I decide to give them the short version. Then Sasha asks, ‘Kakaya u tebya beda?’, which literally means ‘What is the source of your trouble?’ (The closest expression in America would be ‘What are you in for?’) It is the first of many times I am asked this question in the prison system. I check the paperwork given to me by the investigator, then tell Sasha I’m here on a charge of 159.4, ‘fraud of large scale’. ‘That’s really cool!’ he replies. He wants to know how much money is involved. I decide to downplay the figures so as not to appear too wealthy or grand. I tell him it’s a dispute over a loan of 2.5 million roubles ($33,000), a factor of 1,000 times less than the real number. Sasha nevertheless strokes his chin and nods his head gravely, as if to acknowledge what a huge sum this is.

Sasha goes on to tell me his life story. He is a gregarious companion and takes pride in being able to show a foreigner the ropes of life inside. I learn that he’s been married three times, in prison five times previously, and has been arrested this time for stealing someone’s mobile phone. In between spells in prison, he works in the building trade installing windows. But, he tells me, it is hard to make a living this way, what with bills to pay and wives and everything else – you just can’t get ahead. In comparison with life on the outside, he reassures me, prison isn’t so bad. You don’t have any bills to pay and you get to watch TV most of the day. But of course, he says, it all depends on which prison you are sent to. According to his own insider ratings of Russia’s most famous prisons, he considers the nineteenth-century Moscow jail Lefortovo as the best he has experienced so far. He ought to post this stuff on a Prison TripAdvisor, I think to myself.

Ildar is much more reserved than Sasha. I never learn what he’s been arrested for. Occasionally he yells out the window in Chechen, responding to shouts from some other Chechen prisoners in different cells. He spends most of his time exercising, forever doing press-ups. I tell him about a recent bestselling book in America called Convict Conditioning. That immediately gets his interest. We spend an hour comparing ideas on fitness training regimes, and Sasha joins in enthusiastically, too. He shows off his biceps that look like cannonballs. It’s just the way he was born, he insists, and the same with his giant beer belly.

Eventually, I lie on my bed and try to sleep but with little success. The cell is stuffy and hot, an oppressive stench hanging in the air as if from accumulated decades of human sweat mixed with the indescribable horrors emanating from the toilet hole area. The lights are left on, presumably so the guards can look in on us periodically. The squeaky iron gates in the corridor clang open and shut all night long. Adrenaline continues to flow around my body as I try to process what is happening and what to expect next. I wonder if my case has gone public yet or if it’s being kept quiet. And what about my colleagues from Baring Vostok? How are they coping in their cells wherever they might be? I’m still struggling to believe that this is a genuine attempt to arrest me. I just can’t imagine that anyone can seriously try to construct a criminal allegation around a transaction from which we have derived no personal benefit and which had proven genuinely profitable and valuable to the bank. I figure that once a few senior people in the Russian government learn what’s happening, there’ll be a backlash against my accusers – perhaps even prompting an investigation into their historic investments, some of which really are suspicious.

I think about the reaction of the wider investment community to my arrest. I am well known for promoting Russia and defending the country’s image as an attractive place to work and invest. But if word is out about my arrest, anti-Russian commentators in America are probably on TV right now, saying that my detention is yet more proof that no one is safe investing in Russia. I reckon this situation will cause damage to the Russian investment climate by a factor many hundreds of times larger than the amount at dispute with the shareholders. Surely there will be an appetite among the nation’s intelligent and powerful to avoid such harm. As I lapse into brief and fitful sleep, I convince myself that I am merely being sent a message, and that tomorrow I’ll be released back home.

* * *

It’s about seven o’clock and I am sitting in my cell, struggling through my first prison breakfast: black tea with a cube of sugar, a slice of dark bread, and a strange glutenous substance that alleges to be oatmeal. It reminds me of the gruel eaten by Morpheus’ crew in The Matrix, thin and tasteless but just about enough to keep you alive. When I’m done, I roll up my bedding and mattress and place it on top of my small bed, just as it had been left for me. Then I get dressed and await whatever fate has in store for me today. When the guards arrive to collect me, Sasha gives me some of his stash of pryaniki, a sort of Russian molasses cookie. It’s his parting gift, along with a bear hug and a hearty ‘God be with you!’ A reminder of the decency and generosity of ordinary Russians that I have experienced so often in my twenty-five years here.

I am handcuffed and loaded into another convoy truck, this time heading for the Basmanny District Court. I will discover that this is the preferred court for Russia’s Investigative Committee, as it approves almost 100 per cent of their recommendations. In fact, my advocates can’t recall a single occasion when it has opposed the Committee’s wishes. Over the years, it has been the setting for some of Russia’s most controversial trials, like that of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. While I wait for my hearing, I am kept in a holding cell under the court. There are about ten of these cells, each around 3 sq m in size, with no windows. On the walls are scribbled messages, most referencing God or Allah. Each one is signed with the criminal statute number of the accused. One reads: ‘God be with you! Mitya, 201.1’. Another takes a more defiant tone: ‘Fuck them all! Ivan 160.2’. Last night’s lack of sleep is catching up with me. I take my ‘Dolomiti’ black down jacket, roll it into a pillow and curl up on the rough wooden bench at the back of the cell. Before long, my eyes close.

When I rouse, I have lost all sense of time again. Have I been in this dungeon for an hour? Three? Five? Not knowing the time is, I realise, a special kind of torture for those of us used to modern, constantly connected lifestyles. Occasionally I hear someone being escorted into or out of the adjacent cells. Someone is brought into the cell next to me and knocks on the wall three times. I am not sure whether this is some kind of secret messaging system but I can see no downside to sending a return message. I knock back three times on my own wall. This is repeated a few times with the inhabitants of other cells and I find it oddly reassuring, providing confirmation that I am not alone.

Eventually, two guards open my door, put my handcuffs back on, and lead me out of the holding area. One of them gives me a heads-up, telling me that there are a lot of journalists upstairs, so I can cover my face if I want to avoid the cameras. I have always thought that is about the dumbest thing any person can do. A quick way to make yourself look guilty. I have nothing to hide or to be embarrassed about; I have done nothing wrong and I know who the real guilty parties of this piece are, so I determine to hold my head high as I walk into the court. I am not going to give those bastards the satisfaction of seeing me look afraid.

Even so, I am unprepared for the level of attention. Unless you have ever been the subject of intense media or paparazzi scrutiny, you can’t really imagine what it is like to be exposed to the bright glare of a dozen video cameras and the snapping of throngs of photographers, each of them shouting at you in unison. There must be more than 200 people crowded outside the courtroom, but it is such a blur amid the flash of cameras that I cannot make out individual faces. It is a disconcerting assault on my senses. However, I do hear the unmistakable voice of my old driver and friend, Valera, shouting ‘We are with you, Mike!’

The hearing is not about the merits of the case against me, but solely to determine what method of detention I will face during the planned investigation. The best result would be to be released on bail, but I might be detained under house arrest, or assigned to a ‘prison isolation centre’ (SIZO). The judge is Artur Karpov, whom I would later learn has adjudicated in several other notorious Russian criminal cases, including the infamous and tragic Magnitsky case during which Sergei Magnitsky, a lawyer who exposed corruption by state officials, died while in custody. In the courtroom I am put in a cage with glass walls, familiar to anyone who watches Russian TV. There are about twenty people allowed in court at any one time, and most of them seem to be journalists, although I am relieved to spot a few friends and colleagues, too. My advocates deliver a series of character reference letters from a host of my Russian friends (including the cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, entrepreneur Oleg Tinkov, the businessman and politician Ruben Vardanyan, and the internet pioneer Leonid Boguslavsky), as well as bail guarantees from influential Russian business figures, including Kirill Dmitriev and Peter Aven. There is even a letter in my support from the legendary Russian Olympic wrestler Alexander Karelin – a man I have never met! At least, I think to myself, I have not been abandoned.

Then the investigator reads the charges – the first time I am able to hear the details of the accusations against me. According to Yusupov, my colleagues and I have defrauded Vostochny by settling a 2.5 billion-rouble ($33 million) loan to PKB with shares in a technology company, IFTG, that they say are worth only $3,500. My advocates respond on a number of technical and procedural grounds as to why I should not be detained. Then, finally, it is my turn to speak. ‘Almost everything you just heard from the investigator and from my accuser is false,’ I begin. Then I briefly explain the real reason for our arrests, driven by the shareholder conflict in Vostochny. These commercial disputes are in the process of being addressed in the London Court of International Arbitration, I explain, where our accusers face potential liabilities of 17.5 billion roubles ($231 million). My belief that I have done nothing wrong is validated by the conclusions of the Russian Central Bank in a detailed audit report. I tell the court that I believe the accusations I face today are intended to help our accusers gain control of Vostochny and so avoid liabilities for their own actions. I also note several points in the accusation that are simply false.

My arguments seem to be making an impression on Judge Karpov, who visibly winces upon hearing my forthright description of the facts. His weary expression indicates that he understands he is now embroiled in a mess, rather than the clear-cut case that was probably presented to him. The support I have from figures influential in Russian society is doubtless food for thought as he ponders how best to proceed with this charade. He asks for a recess to run until tomorrow. I feel this is a hopeful sign.

I am kept in my cage while the press and other observers file out of the courtroom. I spot my assistant, Sasha, among them, and reach out to make a fist bump against the cage’s glass wall as she walks by. She smiles and raises her fist to bump mine from the other side of the glass, before she is hustled away and scolded by the court security guards. Then I too am led out and loaded back into a convoy truck with several other prisoners. I am the last to be dropped off, and by the time we have made it round several different detention centres, it has been a couple of hours. Arriving at my new temporary detention facility, I am put in a cell with only one other prisoner. Mitya is a tall, wiry man with a shaven head in the classic Russian prison style. He has been arrested for theft. As he chain smokes, he tells me with pride about his early days in the ‘business’ in the 1990s, when he once ‘persuaded’ some railway officials to ‘lose’ a train car full of copper, which he managed to sell on very profitably. After he has regaled me with tales of his adventures, we are joined by a third prisoner, Alexander. I guess he is in his late thirties and his clothes suggest he is a prosperous man. I find out that he owns a business in the aviation equipment sector, and that he is accused of selling important technology and secrets to foreigners. With his broken English, he tells me he knows who I am because he saw me on yesterday’s news. Like me, he is clearly new to this whole system of Russian prison life and is visibly shaken up, breathing hard, moaning, and looking altogether miserable. Mitya, on the other hand, wants to ask me about Trump. ‘What’s he really like?’ he says, assuming that I know him, since we are both Americans. I tell him that I have no personal knowledge of the man and then give my usual balanced assessment of the president, including his pluses and minuses. I can tell it’s not the simple answer Mitya is after. He pauses briefly and says: ‘Well … anyway … tell him hello from us! … And to get rid of the sanctions!’

Time is pressing on and I try to get some sleep but a telephone in the corridor rings through the night at intervals of fifteen or twenty minutes. Just enough that I can’t fall asleep. I close my eyes and try to rest at least, knowing that tomorrow will be another hard day. I breathe deeply, drifting eventually into a sleepless, trance-like state, visualising myself in a suit of armour that I wear to tomorrow’s court hearing, and beyond.

Before I know it, I am eating breakfast again. It feels like Groundhog Day as I consume the same uninspiring food, put on my same jacket and hat, get handcuffed and loaded on to a convoy truck just like yesterday’s. Back at the Basmanny court, I am stuffed once more into one of the same dreary holding cells. At least the wait is shorter today. After extensive press interest in my comments yesterday, this time journalists with video cameras are forbidden in the courtroom, at the request of my accusers. They obviously want to prevent anyone from publicising the real facts of the case. My advocates supply another wedge of character references from even more impressive Russian business figures, some of whom I don’t know personally, but whom I know and admire by reputation. I am moved and encouraged by their courageous support.

Any expectations I have are tempered by my advocates, however, who tell me that my arrested colleagues have already been ordered to be detained for at least the next two months in special prison isolation centres. The chances that I will receive a different decision are remote. I imagine the many phone calls and meetings held by my supporters since yesterday, advocating on our behalf, but no doubt countered with lies being spread by my opponents. I recall Winston Churchill’s description of Soviet politics as a fight between two bulldogs under a carpet; an outsider hears just the growling, and it’s only clear who has won when the bones fly out from beneath the carpet.

I am canny enough to know that one can have many influential friends in Russia, but when factions are competing, it is the FSB who generally have the decisive voice. Clearly they are siding with my opponents, unmoved by the threat of reputational damage to Russia and its system resulting from the unjust arrests of myself and my colleagues. Judge Karpov, who seems fractious today, announces his decision that I should be detained in ‘SIZO’ for a further two months.

One of the witnesses at today’s hearing has been the head of security at Vostochny Bank, and a henchman of Yusupov and Avetisyan, depicting himself as a ‘victim’. He waits until after my sentencing and for all the journalists to leave and then starts filming me in my cage on his phone. I have the sense that he is getting a kick out of seeing me suffer. From his sadistic giggle, I gather he is livestreaming. I suspect Yusupov and Avetisyan are watching, perhaps popping the champagne corks. I try to remain expressionless and refrain from doing what I really want to, which is to shout at them all to fuck off and go to hell. It is one thing to fiercely defend your business interests, but what kind of person gets enjoyment out of seeing another human being suffer? If there really is karma in this universe, this security guy deserves to be reborn in the next life as a worm.

Eventually, I am taken back to the convoy truck. As I am shoved back inside the iron cage and the engine begins to turn, my mind races with images of the kind of misery that awaits me. I expect they will put me under increasing pressure to try to break me and make me confess to non-existent crimes. I imagine sharing a cell with a band of veteran ‘thieves in law’ notorious in the Russian prison system – the sort of organised criminals who have the status of ‘made men’ in jail. How will I cope? I have devoted almost my entire adult life to championing investment in Russia, and convincing other foreigners to share my optimism for the country. I have been notably successful in this, in large part because I genuinely believed it. Now I feel deeply betrayed, bewildered that I could be rewarded with such a fate.

I lean wearily against the wall of the cage, scrunched up in a ball with my handcuffs over my knees, trying to buck up my spirits and stay warm as two days of accumulated sweat begins to freeze on my skin. At last, the convoy truck grinds slowly to a stop. The guard, stretching stiffly after the long ride, opens the creaky metal door to go outside. It is a bone-chillingly cold Russian winter day, about -20° Celsius. After a few moments, I hear the footsteps of the guard, striding back towards the truck. He steps purposefully inside, unlocks my cage and leads me out. The truck is parked in what initially looks like the inner courtyard of a normal Moscow apartment building, except without the usual parked cars, or the customary aluminium ‘rakushki’ storage sheds, and other signs of residential life. But now I notice that this courtyard has no visible exit, and the windows of the surrounding buildings are all barred.

This, I discover, is Investigative Isolation Unit #1 at the notorious Matrosskaya Tishina prison – my new home for the foreseeable future.

2

Welcome to Alcatraz

I spot another guard standing outside the truck and wearing a different uniform, his arms folded across his chest. He says something in awkward English. With his thick accent and odd intonation, it takes me a few seconds to process and understand him: ‘Welcome … to Alcatraz.’ From the grim smile on his face, he is clearly delighting in the arrival of his new American prisoner. He doesn’t intend forhis greeting to be reassuring and it isn’t.

Still handcuffed, I am led through a heavy steel door and up some stairs. I am not yet familiar with the prison rules so ‘Hands behind your back!’ is barked at me at intervals. Every 30ft or so is an iron gate, each requiring keys about 6in long which must be given two or three rusty turns to unlock. As we enter the stairwell, one of the guards presses a button, triggering a wailing siren louder and scarier than anything I have ever heard before. It brings to mind the infamous shower scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho, but slowed down to make it even creepier. Truly spine chilling. I wonder if this is all part of some psychological game, but I realise there is a practical purpose. It alerts other guards to the presence of a prisoner in the stairwell so that the isolation for which this place is designed can be preserved.

When we reach the second floor, there are three more guards waiting for me – a sort of ‘induction committee’, who search me from head to toe. They are all young guys, in their 30s, wearing camouflage uniforms. Since my shoelaces and belt have already been confiscated, there’s nothing else for them to take. They ask a few questions for their forms and welcome me to Matrosskaya Tishina. I know it by reputation as an institution that has housed several famous and infamous prisoners; a place synonymous with misery and despair. In my mind, I see the image of a candle being snuffed out.

I am sent to a small room where a doctor makes a quick check of my temperature and blood pressure. I am surprised to see that my levels are normal, given the stress I am feeling. He also takes blood and urine samples and tells me I will be quarantined for three days while they are tested. I am taken to a cell and it is only now I realise that I haven’t seen any other prisoners in this huge building full of cells. Prisoners mixing, I quickly learn, is considered to pose a risk of information sharing or witness tampering that might thwart investigations.

Compared with my cells from the last two nights, at least this one is clean and comfortable. There is a larger side table to sit at and write or eat, a proper toilet with full walls almost to the ceiling for privacy, and even an old TV. On the wall is a security camera, which recalls to me the Eye of Sauron in The Lord of the Rings. There is a small hole in the door (a shnift) for observation from the corridor, and a speaker through which commands are given. A list of the prison’s rules, along with the rights and daily regime of prisoners, are also displayed. Although my spoken Russian is good, my reading is less so, so it takes a few days to get to grips with what it all says. But I do learn that if I have any complaints, I can contact the Ombudsman, Boris Titov. This is good news as I know Boris from business circles in Moscow. He has a reputation for honesty as well as forging good relationships within ‘the system’. Useful to know.

A guard brings me to the shower room, and I take a hot shower by myself. After two and a half days of intermittently sweating and freezing, I need it badly. I am given just one bar of soap, which is for both washing and shampooing. The floor tiles have that slippery-filmy feel of a locker room shower just after it’s been used by an entire football team. My allotted towel is the size and thickness of a small kitchen rag. But I stand under the hot water for twenty minutes, luxuriating and swearing that I will never again take for granted such a glorious indulgence.

The lights, it is quickly apparent, are kept on in the cells twenty-four hours a day. From around 10.30 p.m. until 6.30 a.m., they are slightly dimmed but never low enough to prevent the Sauron eye from watching and monitoring you even in your sleep. Feeling like a laboratory mouse under constant observation, I lie awake thinking of my colleagues who have also been arrested – all honest men and top professionals who have always acted with total integrity, and who have done nothing wrong. Now they too are in prison, all of them with young families, even younger than mine. It must be especially frightening for Philippe Delpal, a Frenchman who doesn’t speak Russian. I feel responsible for them all.

In the morning I am given an iron bowl, a spoon, and a large iron teacup. The breakfast round is heralded by three metallic raps on the cell’s steel door and the opening of a small square opening, about 12in across. I stick my bowl through, as I have been instructed. I can vaguely hear but not fully see the kitchen ladies who ladle oatmeal into my bowl, along with a big lump of sugar and a slice of black bread. The portions here are larger than in the temporary detention centres, and with the addition of the sugar the oatmeal is even edible. I find out that my bar of soap also has to do for washing up my bowl and cup after meals. This is all far from my accustomed lifestyle, but I realise that I can survive this. As I contemplate my bowl, I am reminded of a promise Mao Zedong made to his followers: having the Communist Party, he said, is like having an ‘iron bowl’, a symbol that you will be fed amply and reliably. Of course, millions of Chinese later starved to death during the Great Leap Forward. I am at least confident I won’t die here because of lack of calories.

It is 8.30 a.m. and the guard comes to my cell as per his regular daily routine. This is the only time a prisoner is allowed to request anything. I ask if he can bring me any English books or newspapers. He explains that every request needs to be submitted in writing on an official request form (a zayavlenie) but, since this is my first day, he’ll make an exception and check. When he comes back, he helps me fill out a zayavlenie for a Russian–English phrase book from the prison library. It is an ancient and well-worn copy, and the guard advises me to use it to decipher the rules on the wall.

I ask if it’s possible to send a letter to my family. He says that normally it is but just now the prison censor is away on holiday. The censor has to check all post in and out of the prison to make sure no hidden, prohibited messages are getting through. ‘When will he back?’ I ask. The guard tells me it will be March or April. I suspect he’s telling me a lie, messing with me. But, no, it turns out to be true. There is only one censor and he gets an eight-week holiday each year. The guard tells me that it is not possible for me to have any newspapers either. I am desperate to know what is being said about my case. He says I can subscribe to certain Russian daily newspapers but only once I have been assigned a permanent cell and have set up a ‘personal money account’ with the prison. This, he informs me, normally takes a couple of weeks to process and can only be done with a zayavlenie.

Late morning, I am taken by the guards up the Psycho-siren stairs to the top floor of the prison for my daily progulka, a one-hour period when all prisoners have the right to walk in the open air. Since this is a SIZO and not a normal prison, this occurs in small open-roof cells where no prisoner comes into contact with any other. These progulka cells have walls about 5m high, then an opening of about 1.5m (covered by barbed wire, but open to the air), topped with a corrugated metal roof. They are only about 20 sq m, with a small wooden bench fixed in the middle of the stone floor. Being mid-February in Moscow, it is bitterly cold. I’m guessing -20 degrees. I ask how I am supposed to avoid freezing. The guard circles his hand in the air and helpfully tells me to walk around until I heat up. Then he locks the heavy metal door behind me and I am left to my own devices. I jog briskly in tiny circles around the wooden bench, and, sure enough, after about ten minutes, I am feeling warm enough to unzip my coat. Music from the Retro FM radio station warbles from loudspeakers, a surreal soundtrack to the pair of machine-gun-toting guards who walk on a gangplank up above charged with surveilling the ten or so open cells up here.

When my hour is up, I feel refreshed and renewed as I return to my cell for the rest of the day. I fiddle with the cell window, which is lined with an opaque film to prevent you from being able to see anything out. At least it provides a little light and I discover it can be opened about 6in to let in some fresh air and offer a fleeting glimpse of what lies beyond. I stick my face into the gap and inhale deeply. Moscow’s winter air and the sounds of normal life in the distance transport me in my imagination to a time when I am walking the streets again as a free man.

Dinner that evening is a bowl of soup and half a fish – overboiled, tasteless and full of bones. But I need the protein and eat the whole thing. I think how amazed my wife would be to see her husband, an Oklahoma boy raised in cattle country, devour it. But with a lot of free time and few distractions, I figure it’s worth the effort to take that fish apart bit by bit with my bare hands. I treat it like a project. I guess I probably look like Tom Hanks in Cast Away, stranded alone on a remote island, slowly sucking on the legs of a crab while staring silently at the horizon. When I am finished, I switch on the TV in my cell, which shows all the main Russian channels. I watch a dubbed Hollywood movie, Law Abiding Citizen, starring Jamie Foxx and Gerard Butler. It’s about a corrupt American prosecutor who lets a vicious killer free, and then the victim’s husband comes back years later to gain revenge on them all. Mentally, I drift off into my own ridiculous revenge fantasies before coming back to reality.

When I try to get some sleep, I am relieved to find that Matrosskaya Tishina is quieter than the temporary detention centres. The Psycho-siren stairs are, thankfully, used only infrequently throughout the night. But there is something other-worldly about the place. I hear an assortment of strange sounds wailing periodically from outside in the courtyards. They make me think of phasers in Star Trek, zapping for about ten seconds, falling silent for minutes at a time, then zapping again. My sleep is further disturbed by my having to get up several times with a bad stomach. Must have been that fish. My volatile American stomach has not taken long to succumb to the combination of balanda (prison food) and my own questionable washing-up skills.