Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In July 1940, Desmond Ibbotson joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve hoping to fly Spitfires. He achieved his dream aged just 19, eventually completing 650 flying hours in seven types of Spitfire. He did two tours of operations with three of the RAF's elite squadrons in the skies over France, North Africa and Italy, was credited with eleven confirmed victories and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar. After a dramatic active service that saw him shot down during the Battle of El Alamein, captured by Rommel's forces and making a daring escape, in 1944 he was promoted and moved to instructor duties at Perugia, Italy, where he trained experienced pilots returning to the front line or converting to a new fighter type. Tragically, just over three months later, Desmond was killed during a routine test flight that November. He was buried in a military cemetery, but serious questions would remain about his death. How had such an experienced pilot crashed while undertaking such a simple flight? And, given that he had a marked grave, when a Spitfire was excavated from an Italian field sixty-two years later, why were Desmond's remains still inside? The product of over twenty years of meticulous research, On Silver Wings is a detailed study that respectfully relays the events of Desmond's short but eventful life, investigating what happened on his tragic final flight and exactly how he came to have two graves.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This colour portrait of Desmond, recreated on a commemorative plate, began the search. (Ibbotson family album)

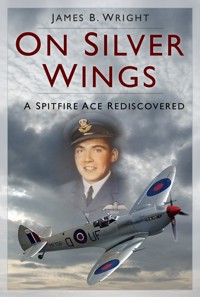

Cover illustrations: Front: Desmond Ibbotson (Ibbotson family archive), Spitfire MK IXe MK356 (Wikimedia Commons/Tony Hisgett); Back: Desmond Ibbotson (Ibbotson family archive).

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© James B. Wright, 2025

The right of James B. Wright to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 921 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

PART 1: The Unofficial Eyewitness: A Chance Meeting and New Questions

An Introduction

1 The Unknown Eyewitness

PART 2: What Happened to Desmond: The Man, the Ace and the Woman He Taught to Fly

2 From Yorkshire to New Zealand and Back

3 No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School

4 No. 8 Service Flying Training School

5 53 Operational Training Unit

6 129 Squadron

7 54 Squadron

8 54 Squadron – French Rhubarbs and Scottish Hail

9 112 Squadron – The Western Desert

10 112 Squadron – The Great Retreat

11 601 Squadron – El Alamein and Escape

12 601 Squadron – The Advance to Tunis

13 The Interlude Between Tours

14 Central Gunnery School

15 103 Maintenance Unit – Test and Delivery Duties

16 601 Squadron – Spitfires Over Anzio

17 601 Squadron – Final Victories

18 601 Squadron and the WAAFs

19 No. 5 Refresher Flying Unit

20 5 RFU – Final Flight

PART 3: The Aftermath: The Family and Two Burial Sites for One Man

21 The Aftermath

22 Sarah Remembers Desmond – The Way to the Stars

23 Sarah Visits Desmond’s Grave

24 Muriel Remembers Desmond’s Death

25 The Re-Excavation of Desmond’s Spitfire

26 Digging for the Truth

27 Desmond’s Story Emerges

28 Desmond is Laid to Rest

29 The Knowns and Unknowns

Notes

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

For June, our family, and in memory ofSqn Ldr Mark Long of the BBMF

Acknowledgements

I first began researching this story over twenty years ago, and I am very grateful to a wide number and variety of people whose contribution deserves recognition. Muriel’s husband, Jim, unwittingly started the whole thing off when he kindly agreed to my interviewing him in the autumn of 2003 about his army days in Italy when he took part in the landings at Salerno, crossing a beach under enemy fire some sixty years earlier. Jim was an ideal interviewee because of the clarity and detail with which he remembered his experiences. A true gentleman, he was always patient with my questions and interesting to talk to. Like many others, Jim served his country faithfully and faced the same dangers as those alongside him who did not come home. After a long life, he died in 2004.

Muriel, understandably, never forgot her brother and made sure her children knew about their Uncle Desmond, the Spitfire pilot. It is thanks to them – Muriel, John, David, Judy and Barbara – who, along with Molly’s daughter, Jayne, all very kindly helped me understand Desmond and research his life. Without their kindness, generosity, support and assistance as a family, none of this would have been possible. After a long and happy marriage to Jim, Muriel died in 2012.

Similarly, I’d like to give a special thank you to Patsy’s son Rob, who very kindly allowed me to discuss his mum’s memoir and reproduce some of that material to give another, previously unheard, side to Desmond’s story and a glimpse of a life he could have enjoyed if he had made it home. Patsy died in 2015.

In addition, I am grateful for the unstinting help, advice, encouragement, patience, humour and forbearance of my (now sadly deceased) parents, my wife, June, and stepdaughters, Caz and Jose, who together did so much in the background that enabled me to complete this work.

Then there are the veterans and their families. Ray Sherk, one of Desmond’s fellow Spitfire pilots, both in training and on No. 129 Squadron, who lived in Ontario, Canada, kindly replied to my letters and sent me a rare photo he took of Norm Peat, Jimmy Whalen and Desmond with a Spitfire. Of these four friends, only Ray survived the war. He clarified an inaccuracy in the official records too regarding his time on 601 Squadron in the desert. Ray continued to fly until the age of 91 and died in 2016 aged 94.

Jamie Ivers put me in touch with 601 Squadron’s biographer, Tom Moulson, who also kindly helped with background information and answered some thorny questions on Desmond’s alleged meeting with Rommel. I am indebted to Rob Brown, who runs the 112 Squadron tribute website – an impressively detailed database – through which I have been able to request help in verifying information from that period of the war. Through contact with his son, G. Howe, D.J. Howe, a Canadian flight sergeant who joined 112 Squadron as a pilot, was able to put names to a previously unidentified group photo. ‘Tex’ Phillips’s daughter, Sarah, kindly passed my questions on to her father, who flew with Billy Drake and Desmond in the summer of 1942. Sadly, her father died not long after, at the age of 93. To have had the chance to communicate with some of Desmond’s wartime friends has been much appreciated.

Gp Capt Steve Lloyd of the Ministry of Defence Air Historical Branch, based at Bentley Priory, provided unique information on Perugia airfield in the early stages of my research and a summary of Desmond’s career from sources not readily available to me at the time.

Sue Raftree of the Joint Casualty Clearing Centre, part of the RAF Personnel Management Agency at Imjin Barracks (since renamed the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre Commemorations team, and informally known as the ‘MoD War Detectives’) in Gloucestershire, helped with background information on the identification process when Desmond’s remains were found.

David Hirst and cameraman Martin of Yorkshire Television very kindly allowed me to tag along with them in Italy for the memorial services.

Leo Venieri and Marco Maiani of Romagna Air Finders helped me to learn more about the team’s work. I thank them for their very kind assistance and their dedicated work in recovering and preserving the memory of many young airmen from all sides who lost their lives in the war.

John Purtell, a Foreign and Commonwealth Office official based at the British Embassy in Rome, very kindly translated for me, both out in Italy when questioning the eyewitnesses and later when translating letters to the witnesses and passages from an Italian book regarding Perugia airfield. Much would still be a mystery, were it not for his efforts.

Thanks to Bruno Cavallucci, Antonio Cavallucci and Eugenio Pennacchi because without them, there would be no chance of ever having an idea about what happened in November 1944. When the ceremonies ended, at the edge of that field in Umbria, this kind and humble gentleman, Eugenio, finally told Desmond’s family his story about that final flight and the recovery efforts he was part of at the time.

Thank you to the staff of The National Archives, Royal Air Force Museum Hendon, Imperial War Museum (Department of Documents and Department of Photographs) and the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King’s College London, who all kindly fielded my numerous queries with much patience and efficiency.

Oreste Martini kindly flew Bruno, Eugenio and me over the crash site at low level and over the Rivotorto cemetery. He was proud to have flown with his small display team, ‘Walter’s Bad’, over the cemetery on the day Desmond was reburied. He and his colleague Claudio Munalli, the secretary of Perugia Aeroclub, kindly provided contemporary photos of St Egidio airfield and a book about the airfield’s history. Claudio’s father, Luigi, was actually a sergeant in the Italian Air Force based at the airfield when the Allies captured it and was given special dispensation to work with the British at the airfield for the time they were there.

More recently, as research led to writing, meeting Shelley Harris, Helen Fields and Diccon Bewes in 2012 at West Dean near Chichester in West Sussex proved both inspirational and motivational. Seeing them go on from early success to release more titles and flourish, sometimes in the face of very difficult challenges along the way, has kept me going and given me many happy memories too. I’d also like to express my deep gratitude for Stephanie Butland and her professional oversight and expertise in managing both me and my writing, through various rewrites to completion. To conclude the journey to the finished article has taken the very kind assistance and expertise of Amy Rigg and the fantastic team at The History Press to bring this book to life.

Lastly my thanks goes to Desmond and Patsy, because his logbooks and memorabilia (now in the Yorkshire Air Museum) and her memoirs (now in the RAF Museum) are precious artefacts through which we understand what happened. Desmond’s logbooks evolved into a diary which, with typical understatement, reveal the enjoyment, frustration, fun, courage, hope and danger he experienced. Like so many others, Desmond did not live to see the end of the war itself. It is, therefore, to the young men and women of that generation that the final thanks of all must go. I hope this story does them justice.

Every effort has been made to ascertain copyright throughout, but in the event of any omission, please contact the author, care of the publisher.

PART 1

The Unofficial Eyewitness

A Chance Meeting and New Questions

An Introduction

Hotel GiottoAssisi, Umbria, Italy, 8 June 2007

The press conference ended. People, some in uniform, others in smart civilian clothes, shuffled and pardoned their way past each other and fought their way to refreshment: a cooling drink from the bar or a waft of air from the gentle, cool breeze drifting up the side of the valley, over the medieval rooftops.

A small cluster of people remained inside the function room for the time being, gathered round those who were involved in the story and the journalists who wanted more details from them.

I wanted to talk to one of them myself – the official eyewitness. I had travelled a long way, from the north of England to central Italy, to attend the press conference that would precede the ceremony of reinterment for Desmond Ibbotson scheduled for the following day. I had journeyed into Desmond’s life and death and grown to admire him enormously. What had started out as researching a few additional facts to add to the family’s knowledge and understanding of what their relative had done had turned into a personal quest to find the truth behind his untimely death and reveal the full extent of his daring exploits.

Desmond had lived the kind of life I had only imagined or seen pictured in comics when I was a boy – characters who faced their ‘death or glory’ destinies with resolute determination, often in the face of overwhelming odds. Duty called and decent men did as they must. As Churchill said in 1940, ‘We will defend our island, whatever the cost may be.’1 That same man, Desmond Ibbotson, whose ceremony I had come to attend, had been a Spitfire pilot and a decorated ace in November 1944.

In my view, Desmond Ibbotson was much more than a comic strip hero; he had, in fact, been one of the best fighter pilots of his generation until he had been killed flying a Spitfire in November 1944. His sister Muriel, four years his junior, had grown up with him until she was almost 14. Then he joined the RAF and was later posted overseas. She did not see him after the spring of 1942 and was certain he had died in an accident – the records said so, and he had a marked grave that the family had visited in the years since.

These were the established facts that formed the basis of Muriel’s family story. Strangely, Desmond was not the reason I initially met Muriel. Four years before flying to Italy, in 2003, I had gone round to her house to interview her husband, Jim, about his experiences from the landings at Salerno through to the prelude to the Battle of Monte Cassino. As I made to leave at the end of our last meeting, Muriel arrived home. I asked her whose face was on the picture-plate that hung on the white wallpapered wall of their front lounge. Muriel replied that it was her brother, Desmond, a Spitfire pilot who had been killed on a test flight. The sense of mystery about the death of a Spitfire pilot and my deep interest in RAF history drew me in. I wanted to find out more about what had happened. Desmond had never been forgotten by his family. Aside from the picture, Muriel had named her eldest son after him: John Desmond. Now, at this afternoon’s press conference, Desmond’s nephew had sat at the long table on a small stage with officials from the British Embassy in Rome.

Fourteen months earlier, a story about Desmond had hit the national press, both in the UK and Italy. Now he was hitting the headlines for a second time. Desmond had been in the papers a couple of times when he was alive, and he had enjoyed the recognition. Despite the upset the recent media attention had brought, we all agreed he would have loved to have been here and heard us talking about him. I would have given my eye-teeth to have shared a bottle of whisky with him and hear his stories about his time flying Spitfires over Yorkshire, France, Libya, Tunisia, Egypt and Italy. I had been in touch with some of the pilots he had flown with, and all it had done was fire me up to hear more.

It was in this very hotel, the Hotel Giotto, almost certainly this very room, nearly sixty-three years to the day that Desmond had been partying with his fellow pilots, drinking and carousing late into the night, dancing to a swing band until last orders, then drunkenly swaying down the newly liberated streets of Assisi singing a well-known anthem of the Third Reich – Horst Wessel’s ‘The Flag Raised High’ – and laughing like drains. So, when the reporters in the conference asked John what kind of man Desmond was, I wanted to call out from the back row, like someone interrupting a wedding ceremony, and tell them what I knew.

‘He was a dashing Spitfire ace, an accomplished pilot, but he was also someone who loved fast cars and had an eye for the ladies,’ John informed the audience. All of which was true if leaning towards a caricature straight out of those 1970s comics. There was more to Desmond’s life and death than had previously been reported though.

As the meeting closed, I headed for the official eyewitness. He was a distinguished-looking gentleman, around 70 years of age, with a full head of silver hair neatly clipped at the sides and brushed back. He was clean shaven and wore an expensive-looking dark suit with a light-pink shirt that was open at the neck. To one side of him were a couple of British Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials, one of whom, Francesca, was also a fluent Italian speaker. She introduced us – his name was Bruno – and he agreed we could talk outside later.

Out on the veranda, I joined the Yorkshire Television crew I had met the previous evening. They were interviewing a stout Italian gentleman called Leo Venieri who had been one of the four panel members on stage and who had led the team of aviation archaeologists who had found Desmond’s remains. David, the reporter, put me to use holding a fold-out reflector screen while Martin, the cameraman, began filming David interviewing Leo. I did as I was told until the interview was over.

As we were packing away and making polite chit-chat, I fell into conversation with a young English-speaking Italian man called Dario, who I guessed to be in his late twenties or early thirties, with long dark hair and slender features. He also had an interest in the story, and he agreed to translate for me, so I approached Leo and asked if I could interview him.

I introduced myself and explained that I was researching Desmond’s story. I thanked Leo for his email informing me that Bruno would be attending the event today as the official eyewitness and asked if he could join us at some stage. He agreed, and I hastily drew up a list of questions for Bruno. Dario and his girlfriend, who sat diagonally across from me, were making a documentary about the story. Dario leant back against the railing, took a long draw on a Camel Light cigarette and, in a well-practised exhalation, cocked his head back slightly and directed the smoke upwards.

After asking Leo a few questions, I turned to the details of the crash itself. How had it happened? What did the eyewitness see? He answered them in a proficient but considered manner. Part way through, Bruno appeared to one side of Leo. He drew up a chair and listened to Leo’s introduction.

The officer who had led the press conference, Cdr Shawn Steeds, the naval and air attaché based in Rome, had mentioned Bruno but only to a limited extent. Bruno was only 7 years old at the time. He had been standing in the kitchen of his house when he heard an explosion outside. I asked Bruno more about what had happened. Although only very young, he remembered it vividly. He described what he thought had been a bomb going off and had been too frightened to go outside. As he talked, I took notes and went over some of the same questions I had asked Leo separately just a few moments before, in an effort to judge the consistency of their answers and see if Bruno would reveal any other morsels of information – something that would explain not just the ‘what’ but the ‘how’ and perhaps even the ‘why’ Desmond had been killed.

With the interviews over, a short time later, I drove David and Martin to the crash site. John and his brother, Dave, and sister, Judy – the other members of Desmond’s family attending – were going to be there, and they wanted to film the family’s reaction to visiting the spot where Desmond’s Spitfire came down.

We made our way through the narrow streets of the old town, emerged in a small cavalcade from one of the old stone-walled gateways over the street, onto the main highway and snaked our way down the hill to the valley floor once more. I had failed to find the place earlier. Now, with an embassy official in the lead, there would be no trouble.

Heading parallel to the north side of the railway line and round the hairpin, visible only at the last minute, is a small junction. We turned right, following the road under a railway bridge, and turned left at the junction immediately on exiting from under the bridge. Parallel to the railway once more and past a factory was another, hidden, junction. This road was narrower still. Only wide enough for one vehicle and, with fields on either side, I understood now why I had not found it. This little lane meandered off round field boundaries, past isolated farmhouses and dirt tracks for another 2 miles or so before hitting a straight stretch. The road was now hidden from view by a field of tall sunflowers to one side and, behind a tree line, level fields full of ripening wheat on the other. Only a local would have known this area, or indeed have had any reason to come down here at all.

Our little convoy slowed and began to park up. Opposite the slight embankment that bordered the field of sunflowers, and between a gap in the old trees lining the opposite side of the road, was the memorial. One or two of the locals had been tending the site, making sure all was ready for the ceremony the next day. As we arrived, they took the cover off the stone and stepped back from the flower bed at the front.

There, in a little white gravel bay offset from the road, at a point where the ditch was crossed by a concrete land drain, was a large stone. It looked about the same size and rough shape as an aeroplane’s tailfin. On its polished, white marble-like face was black engraving and a black and white photo of Desmond in an oval surround. I recognised it immediately; I had seen the image in Muriel’s photo album several years before. It was a full-faced, sepia-toned portrait of him in RAF battledress, laughing. It had been taken on the afternoon of 8 November 1942, following his safe return to his squadron. Written records suggested Desmond had been shot down while on a patrol, possibly seeking to kill the very man it was said he had escaped from – Erwin Rommel, the legendary Desert Fox. Desmond had survived a crash-landing, escaped from the Germans and walked home – just like that. No wonder he was laughing about it – he couldn’t believe it himself. Two years later he had been killed, here in Italy, in another Spitfire crash.

This was it then. The actual field in which Desmond’s Spitfire had come down. It was noticeably silent, peaceful in the approaching summer evening. Everyone had retreated into their own thoughts and was taking in the scene. A minute or two went by, then John stepped forward and leant out to touch the picture to the left side of the stone face. I surreptitiously took a photo, conscious of the fact this was the first time anyone from Desmond’s family had actually been here. Everyone believed he had been buried in 1944 in the Rivotorto military cemetery that lay a few miles to the north-east. So, when Leo’s team of archaeologists found Desmond’s remains in this field, inside the remnants of his Spitfire, it begged the question: just who was buried in the grave marked with Desmond’s name?

David and Martin slipped quietly into news mode again. Martin raised his TV camera onto his shoulder and began recording some footage while David waited for the right moment to approach the family. I walked to a position about 50m away and tried to work out which way Desmond’s Spitfire had been flying to end up in this particular field, and where it was in relation to the nearest village, Castelnuovo. When I looked again, I noticed Martin now had a digital camera in his hand. He stood in the road, taking photos. One of them would be on a newspaper’s front page the next day.

I climbed the small embankment and stood in front of the regimented rows of sunflowers facing Desmond’s memorial. The sunflowers were each 6ft tall and had, in unison, tracked the sun across the sky through the day. Now every one of their large dark faces stared silently and directly towards the west as the day’s end approached. Every inch of land had been used in cultivating this densely packed crop, and I stood unsteadily at the top of the 3ft-high slope trying to keep my balance on the loose soil. Assisi was still visible in the distance. I recalled the photos Romagna Air Finders (RoAF) had taken from the actual excavation site, and everything now fell into place. The background and orientation of the photos made sense at last. They had not been digging between the military cemetery and the Assisi ridge, as I had first thought; they had been digging over to the west and a few miles further south.

I looked back to the stone and saw Desmond’s relatives – John, Dave, Liz and Judy – in a group embrace. They were no doubt thinking not only about Desmond, but of their mum, Muriel, who had been unable to make the long journey. After half an hour or so, we all returned to the Hotel Giotto. In the hotel foyer we made informal plans for the evening. I had already agreed to meet up again with Dario and Leo that evening. Dario had asked for some help in understanding what Desmond had been doing in Assisi before his accident. I returned to my hotel in Santa Maria degli Angeli briefly before setting out again to meet Dario and Leo at their hotel by the railway station at 7.30 p.m. On arriving, though, I found they had left a note at reception to say they planned to go to the crash site separately and would meet me there. I set off again in fear of missing them altogether.

There were no other cars at the crash site when I arrived, and it was still pleasantly warm. This time, I stood in the road for a moment. The silence emphasised the fact I was alone here. I checked my watch and cursed under my breath. It was 7.35 p.m. now. I resigned myself to the fact I had missed Dario and Leo, or perhaps they had decided not to come at all. I looked across the fields. The only sounds were a dog barking in the distance and the odd ripple of birdsong drifting from the trees. I sighed and decided instead to use the time here as best I could to make a few notes and take photos.

I took out my camera and positioned it so the sun was just visible behind the memorial. The way the memorial stone had been placed, facing towards the lane, meant the sun would now set directly behind it every day. I recalled Laurence Binyon’s famous line from the poem ‘For the Fallen’, which is recited every Remembrance Sunday: ‘At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember them.’ At this time of year, looking east towards the field of sunflowers, it appeared as though each of them were lined up on parade in front of the memorial.

After a few minutes I replaced the camera and unfolded my notepad. Finding it was difficult to write properly kneeling down with the pad balanced on one knee, I put the pad on the ground, knelt on the gravel facing the memorial and started making notes, trying to picture the field as it might have been way back in November 1944. A car pulled up in the lane. It must have looked as though I was praying. I expected it was just Dario and Leo arriving at last so did not look up initially.

I heard a car door close and glanced behind to see someone slowly walking across the tree-lined road towards the memorial. As the figure drew closer to me, I looked up to see an elderly man wearing a checked shirt and brown trousers fastened with a belt standing there, hands behind his back watching me curiously. He had not been at the press conference that afternoon. From his casual appearance and gentle, inquisitive demeanour, I took him to be a resident from one of the farmhouses that were dotted around the area. He looked at me, then at the memorial. He moved forward to touch it and started saying something in Italian, but I had no idea what. He smiled at my confusion, fixed my gaze with his soft brown eyes, pointed at my notepad and started talking slowly. Then he made a diving gesture with his hand and a whistling sound as his hand swept down. He finished with a ‘whooshing’ sound and the use of both hands to then indicate an explosion.

Now the penny dropped, and the hairs stood up on the back of my neck. I looked towards the centre of the wheat field directly in front of us, beyond which, to the far west, the sun was now setting, its rays giving a warm golden hue to the feathered ears of wheat that swayed gently as eddies of warm breeze danced across them. I fumbled for words to ensure I had understood what he was indicating. I turned to face the memorial. One Italian word stood out etched in black upon the white marble-like stone of the memorial, pilote, and the surname alongside it, ‘Ibbotson’. I repeated his gestures back to him and pointed to the centre of the field. The elderly gentleman smiled and, looking in my eyes, said simply, ‘Si.’ The hairs on my neck refused to lie flat. In the stillness of a warm summer evening with the sun about to fade, I stood somewhere in the middle of the Umbrian countryside next to an unknown gentleman who seemed to be trying to tell me he knew something about Desmond’s crash. I spoke no Italian, he spoke no English, and there was no one to translate.

The sceptic in me began to question my initial thoughts. I tried to work out his background. He looked the right age, mid-seventies to eighties. His face was naturally lined and though not pale, neither was it red and weather beaten like that of a typical farmer. Who was he? Where had he come from? And where was an Italian speaker when I needed one?

I tried again to understand what he was saying. He ventured a few words in French. I replied in my very limited French to say simply that I was writing about Desmond and offered a few basic details about him. Then another idea came to me. I took out a pencil and flipped the paper on the pad over to a new page. I sketched a couple of tall trees and the field in front of us. I added a couple of artillery guns and a Spitfire diving down towards the ground with flames behind it. Using the sketch, a few hand gestures and words in French, I tried to communicate my thoughts more effectively. The elderly gentleman watched what I was doing intently. We sensed each other’s frustration at not being able to completely understand each other, but I felt we were on the verge of a breakthrough. I showed him the sketch and asked him in French, ‘Did you see the accident of the pilot Ibbotson in 1944?’

He turned and held my gaze with his now misty eyes. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘I saw everything.’

CHAPTER 1

The Unknown Eyewitnes

A field near Castelnuovo8 June 2007

I looked out across the field in front of us and tried to picture the scene sixty-two and a half years ago. Where had this man been standing, and what might he have seen? I knew only that the Spitfire had been on an air test, Assisi was in Allied hands and the front-line troops were 300km further north by that stage of the war. Bruno had described an explosion. This stranger next to me indicated that he had seen the same explosion.

Above my sketch of a Spitfire, I drew the mushroom shape of an open parachute with lines focusing to a body underneath. From the tail section I drew sharp zigzags as though a fire had taken hold and caused a pilot’s worst nightmare – trapped in a burning aeroplane as it fell to earth.

Surely, if he had been shot down and the aircraft was on fire, Desmond would have tried to escape. I pointed to the parachute and asked the gentleman beside me if he had seen one. He looked, pointed to the stick man on the end of my pencil parachute then turned to face me and said simply, ‘Non.’ I looked again at the memorial in front of me. The face was white marble with faint veins running across it. On the left side of the stone, just next to Desmond’s picture, was a large semicircular grey gouge. What could simply have been the result of a machining process, where the cutter had struck a hidden fault line beneath the surface causing it to shatter and break off, had revealed a subtle, graduated depth. It looked as though the stone had been shot. The rough-edged white stone with its bullet-like wound reminded me of the many times Desmond had himself been shot at.

We talked a little more in French as I added some other potential hazards Desmond could have faced, but each one was met with an emphatic ‘Non.’ The sun was casting soft golden hues across the wheat tops, and the shadows were lengthening. As we drifted slowly back to the roadside, I asked the gentleman if he was going to the memorial service tomorrow. There was his favourite word again: ‘Non.’

‘Would you like to come to the service tomorrow?’ I asked.

He smiled and nodded.

I showed him the timetable of events the RAF and Italian authorities had lined up. He agreed to go to the cemetery but did not look keen about going back to the Hotel Giotto afterwards, so I didn’t press the matter.

Before we parted, I introduced myself and asked him his name. ‘Pannacchi,’ he said, ‘Eugenio Pannacchi.’ With a final farewell, he got in his car, a beaten-up Fiat with creaky doors and no power steering, and drove down the lane heading south towards the tiny village of Castelnuovo.

PART 2

What Happened to Desmond

The Man, the Ace and the Woman He Taught to Fly

CHAPTER 2

From Yorkshire to New Zealand and Back

1921–1940

In the first twelve-month period of Desmond’s logbooks, there is no indication that he was an exceptional pilot. Indeed, he had hinted at having doubts himself. Yet the photos of his early childhood do not suggest he lacked confidence. Desmond was Horace and Sarah’s first child and only son, born on 25 October 1921. Of all the pictures the family have of him, there was only one in which he was not grinning. It was taken on a visit to Albert Park in Auckland, New Zealand and, within the family group, only Sarah is managing to smile. Fifteen-year-old Desmond is on the far right of the picture, Horace the far left. Desmond bears a strong resemblance to his dad.

Desmond, loved by both parents, was adored by his mother. His dark hair, cheeky smile, happy disposition and blue eyes meant he could easily turn on the charm and get away with things that both his younger sisters, Muriel and Molly, would not, such as stealing sweets from the jars behind the till in his maternal grandma Ada’s village post office when he thought no one was looking.

His family was tight knit and well known in the West Yorkshire village of Harewood. The house they lived in was tied accommodation: built and owned by the Earl of Harewood, whose family seat is the stately home Harewood House. Many of its residents, including Sarah, were employed by the estate. As a young man, Horace had joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in the First World War. After the war, he left the Army and took a job as the village postman. Ada ran the post office in Harewood.

Desmond preferred not to be called Desmond and was always known as ‘Des’ to his family. His school friends nicknamed him ‘Dibby’. His RAF mates called him ‘Ibby’. During his time at school and beyond, Desmond took after his father in enjoying sport – playing football and cricket for the school and village teams – but by playing to win and tackling others willingly, he developed a reputation for being a ‘hard’ footballer. Yet these were traits that would prove useful in the long run.

Desmond left Harrogate Grammar School in 1935. That same year, Sarah’s father, Wilson McKie, came to stay with them at Harewood while on a trip around the world.1 This wealthy, opinionated stranger from a distant land was also a communist. In talking about his life in New Zealand and the prospects for new immigrants, Wilson perhaps sensed his daughter was struggling and wanted to provide for her. His visit forced Horace and Sarah to think about their own lives and what sort of future they wanted for their children.

With a population of only just over 1.6 million people in 19352 that was overwhelmingly anglicised in both language and culture, Wilson assured the Ibbotsons they would be able to settle, afford a larger house and secure employment with a higher income.

At the time of his visit, a few of the milestones that would lead to war had passed. Hitler had become Chancellor in 1933, then Führer in 1934. In 1935, the existence of the Luftwaffe was revealed, and the Italians invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Within six months, having already returned the Saarland to Germany, troops of the Wehrmacht occupied the Rhineland. Then, in 1936, the Nazis declared their support for General Franco’s fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War.

After Wilson returned to New Zealand, the Ibbotsons considered the move. Perhaps fears of war persuaded them, or perhaps they saw the opportunity for a fresh start. Yet it was almost a year after Wilson’s visit that Horace and Sarah and their three children finally left Harewood for New Zealand. They boarded the ocean liner MV Rangitata at the Port of London on 13 October 19363 and sailed westwards via the Panama Canal and Pitcairn Island to start a completely new life. They arrived in Auckland a month later, during the early Antipodean summer.

Wilson not only paid for the family’s passage to New Zealand but, in line with government entry requirements, agreed to sponsor the family from their arrival into the country, which meant he was committed to finding them employment as assisted immigrants. He gave Horace and Sarah some money to buy a property in one of the city’s leafy suburbs, which they converted to a bed-and-breakfast guest house.

Desmond had turned 15 while at sea, at just about the time they were passing through Panama, and soon after arriving in Auckland, he enrolled at Seddon Memorial Technical College to learn a trade; working in a B&B clearly did not appeal to him. Although the country lacked a significant industrial base, there was a demand for skilled tradesmen, and the college offered courses in engineering and the building trades, including plumbing, carpentry and joinery.4

As the country’s second city, Auckland offered the best opportunity for the family to establish themselves. Yet, as Desmond was finding his feet, Horace found it a struggle to settle down. Whether it was down to homesickness, a lack of prospects for him personally or that he resented the family being bankrolled by his father-in-law is unclear. Ultimately, it was Horace’s decision to return to the UK, and if the family were to stay together, they would have to go with him. So, just six months later, on 6 May 1937, the Ibbotsons boarded the MV Rangitane and set sail for London.5 After almost five weeks of travelling, the family arrived back in Harewood. Horace returned to work as a postman. Sarah took a job as a housekeeper at Harewood House. Muriel enrolled at Harrogate Grammar School to resume her education and Desmond, having taken carpentry and joinery classes in New Zealand, resumed his courses at night school. After completing his exams, Desmond managed to secure a job as an apprentice draughtsman at Cyril Stubbs & Co. Ltd near Leeds. The firm also had a sideline in coffin making. One evening, while having tea with the family, Desmond commented how much money he believed there was to be made in undertaking. Then, in front of his churchgoing parents, added, ‘Though, if I had my way, I’d nail ’em all in face down!’ Muriel thought this comment typical of Desmond’s ‘wicked, devilish sense of humour’.

As Desmond improved his skills in joinery and carpentry, in his spare time he made a beautiful sideboard for his parents. The craft also developed his judgement and patience, imbuing him with another sense that only comes with time and practice: ‘a feel’. That sensory link between hand and eye improves the judgement of how much pressure to apply where and when.

These skills may not seem relevant at first, but an aeroplane is the tool with which the fighter pilot practises his craft and which requires that same intuitive feel. A pilot develops a balance between movement, muscle pressure and hand-eye coordination: left hand on the throttle, right hand on the control column while looking outside of the cockpit to judge the aeroplane’s position relative to the ground or another aeroplane. With practice, as with a joiner’s ability to cut and shape wood, a pilot’s movements on the controls become instinctive, precise and smooth. A Spitfire especially required a delicate touch when handling it. The skills Desmond acquired in the classrooms and workshops of New Zealand and Yorkshire provided a unique grounding in ways that enabled him to fly a fighter plane instinctively when the time came.

In 1939, Desmond turned 18 and the stories in the press about the RAF’s early exploits caught his attention. The night after war broke out, a Bomber Command squadron based at Leconfield in East Yorkshire became the first unit to conduct a raid on Germany, albeit to drop leaflets. After the Nazis invaded Norway and the Benelux countries in spring 1940, the newspapers and newsreels covered the desperate scraps the RAF fighter squadrons found themselves in as they tried to stop the Blitzkrieg rolling on through France. Then came the retreat from Dunkirk and, from mid-July as the RAF began to experience the first large-scale air raids on its airfields and radar stations, the imminent threat of invasion during the Battle of Britain.

During the First World War, pilots in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) were exclusively officers. Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were allowed to fly only as gunners and observers. The services reflected both the societal structure from which the men were drawn and the attitudes of the senior officers. The RFC recruited volunteer pilots from the Army, many of whom were drawn from the cavalry regiments; the adage being that if they could ride a horse, they could fly an aeroplane. The RFC merged with the RNAS to form the RAF on 1 April 1918, and the preference to draw officers from public schools with the right background and money prevailed into the Second World War. Yet the RAF was arguably more forward looking in some areas than its forebears; it also encouraged recruits from non-public school backgrounds with technical skills.

It was at this point that Desmond decided to apply to join the RAF and took the bus into Leeds to sign up. He was successful at the interview and was sent to attend No. 9 Recruit Centre, Blackpool on 2 May 1940. Muriel said Desmond was inspired to join up after hearing about the exploits of RAF fighter pilots in the Battle of Britain, although this took place after he had signed up. One likely role model was Ginger Lacey. He was certainly the ‘local hero’ type, having seen action in France. Lacey was a fellow Yorkshireman, born in Wetherby, educated at Knaresborough Grammar School, who spent his early career as a sergeant pilot. Men such as Lacey showed Desmond that if he had the aptitude, social class might not be the barrier it had once been. And if recent history was anything to go by, compulsory conscription for every man of fighting age beckoned eventually.

Desmond was enlisted into the RAF Volunteer Reserve on 22 July 1940 at No. 3 Recruit Centre at RAF Padgate near Warrington where he attended No. 10 Aviation Candidates Selection Board for further aptitude tests, medical assessment and interviews. He passed these and was selected for training as a pilot/observer – a continuation of the First World War classification of aircrew. Desmond was then sent to RAF North Weald, a front-line airfield, on 17 August just at the height of the Battle of Britain. Glimpsing what may lie ahead for him, Desmond could see and hear the Hurricanes of 56 Squadron taking off to join other fighter formations as they tried to prevent the Luftwaffe attacking targets both in and surrounding London. After North Weald, he was ordered to attend No. 1 Receiving Wing at Babbacombe, near Torquay, in Devon, on 6 September for two weeks. During this time, he swapped his civilian clothes for an RAF uniform, learnt the basics of RAF discipline (how to march and salute) and was issued with his ‘dog tags’, or identity tokens, to be worn around the neck: one fireproof, one waterproof. These were hand-stamped with the wearer’s initials, surname, service number, religion and the service (i.e. RAF) and would be used to identify him in the event of his death.6

Desmond was next posted to No. 2 Initial Training Wing (ITW) near Cambridge on 20 September 1940, to undergo six to ten weeks of training, including more drill and physical training (PT). The ITW trained aircrew of all trades (not just pilots but observers, flight engineers, bomb aimers and others too). Pilots were issued with their ‘Sidcot’ flying suits and studied navigation, meteorology, Morse code, RAF law and theory of flight.7 Desmond did not record his experiences of basic training. Instead, it is only when he began flying training that his personal record starts, as he made notes in his logbook alongside the official record of each flight, despite uniformed personnel being forbidden from keeping journals or diaries while in service.

After finishing his basic service training, Desmond was sent back to Yorkshire to begin flying Tiger Moths at No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) based at Brough in East Yorkshire, on the north side of the river Humber, a few miles west of the city of Hull.

CHAPTER 3

No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School

Brough, Yorkshire7 December 1940–26 February 1941

Here the student pilots had their first real contact with the RAF’s aeroplanes as the focus switched to learning to fly, and they continued their ground school studies. Desmond took his first flight in a de Havilland Tiger Moth DH-82A biplane on 10 December 1940. Exposed as he was to the draught from the propellor on a winter’s day, his first flight was very chilly despite the thick overalls, fleece-lined boots and gauntlets and leather helmet he wore.

The Tiger Moth had a single engine, two-bladed wooden propellor, tandem open cockpit and was constructed of doped fabric stretched over a wooden airframe. Slow, stable and manoeuvrable, it was an ideal airframe on which to learn the basics; it would forgive most ham-fisted pilots their errors. The instructors were not just assessing their students’ ability to coordinate their hands and feet on the controls and fly the aeroplane in the right attitude at precise speeds and altitudes; they were also looking for their student’s ability to follow instructions and understand what was happening around them. Desmond had been both a Boy Scout and an altar boy in his pre-teenage years and was good at sports, so he had the latent qualities needed: the capacity to obey instruction, confidence and coordination. War now brought a purpose and aroused many young men’s sense of adventure and duty. Importantly too, he now wanted to fly the most advanced fighter of its day, an aeroplane that would become a British icon. He wanted to fly a Spitfire.

Desmond’s home life had been turbulent of late, following the family’s short-lived emigration to New Zealand and the emerging distance between his parents, whose marriage was vacillating between loving success and argumentative failure. As he began his first training course, he could be forgiven if he felt relief at being away from Harewood for the next ten weeks.

As a trainee, Desmond would watch the demonstration of a manoeuvre, listen to the instructions, then repeat the exercise exactly as the instructor had shown him – watch, listen, repeat. Did it wrong? Do it again. Not precise enough? Do it again. And so it went on until either Desmond failed the exercise (and therefore possibly the entire course) or the instructor declared it a ‘pass’ and moved straight on to the next exercise. After ten days of training, Desmond noted his first rising doubts in his logbook: ‘I don’t know if I’ll make a pilot yet.’ Student pilots were expected to go from their first flight with an instructor to taking the aircraft up solo in around 10 hours, and the twenty or so flights in the run-up to that goal were demanding given the variety of things to monitor and skills to master. The feeling of public failure and humiliation in front of your colleagues was ever present, as was the feeling of letting down your instructor.

Three days after his note of self-doubt, with 10 hours and 50 minutes of training under his belt and a successful ‘check ride’ with his instructor, Sgt Hewlett, Desmond went solo on Christmas Eve. ‘Hooray!’ he wrote. His skill as a pilot thus far was rated ‘average’ and he remained on course.

As part of their ground training, Desmond and his course mates also completed several sessions in the Link Trainer, the RAF’s first real simulator.1 Here too, Desmond was rated ‘average’, and his instructor stated he was ‘inclined to overcontrol’– in pilot slang, known as ‘chasing the instruments’ – as he tried to achieve, then maintain the required readings on the dials.

Following three more weeks of training and having accumulated a total of 45 hours and 50 minutes flying time (dual and solo), Desmond, now a leading aircraftman (LAC), had completed his first flying course. To top it off, his superior officer rated his character as ‘Very Good’ in his end of year assessment.

Desmond felt more optimistic this time as he wrote, ‘Posted onto single engined aircraft. I might make a fighter pilot yet.’

CHAPTER 4

No. 8 Service Flying Training School

Montrose, Scotland8 March–20 May 1941

Desmond spent three months learning to fly the Miles Master, a single-engined, low-wing monoplane that was closer in appearance and performance to the front-line fighters it served as a bridge to. For the first two years of the war, pilot training was still mainly carried out in the UK. Eventually, the Empire Air Training Scheme and its companion, the British Flying Training Scheme, enabled the RAF to send trainee pilots overseas to certain members of the empire or the USA respectively, to carry out their training in safety. In the meantime, the safest places in the UK were the north of England, Wales and Scotland.

Although it too had a wooden airframe, the Master had a top speed of 300mph, which meant it was only between 30 and 70mph (depending on the engine type fitted) slower than the Hurricane fighter, which the successful trainees would progress to next. ‘Jerry’ Jarrold, who was also learning on the Master in early 1941, recalled:

The Master II was an excellent training aircraft and after the Tiger Moth it seemed to us to be like a fighter and had the same exhilaration when you flew it solo – which of course was the whole point. It seemed a massive aircraft and far more solid after the Tiger and very fast. We always made 3-point landings and you had to settle it in, which was good training for a Spitfire as the technique was the same; by the end of my Spitfire period I could drop the aircraft down on a spot. There were a few Hurricanes at the School and in the latter stages of the Course some chaps got to fly these, which, as we all thought we were heading for fighters, would have been a nice end to the Course.1

Montrose was not just a training base. Located on the Scottish east coast between Dundee and Aberdeen, the airfield faced the North Sea across which lay Nazi-occupied Norway. It was, therefore, within flying range of the Luftwaffe’s fighter and bomber squadrons. As one of several airfields that guarded the approaches to Edinburgh, the Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons based there were responsible for defending the city and the naval bases at Rosyth and Cromarty from enemy raiders, conducting patrols and providing air cover for convoys passing through the North Sea.

The destinations of the trainees on the course that preceded Desmond’s were varied. Of the forty-two successfully posted out, seventeen were officers, twenty-five were sergeants and all of them went off to join their respective operational training units (OTUs). There were thirteen ‘wastage cases’: five were killed, five transferred to twin-engine types, one was re-coursed to No. 28 course, one was rejected as unsuitable and the last individual, LAC P. Mitchell, was sentenced to 112 days’ detention by the district court martial for committing a low-flying offence on 24 February 1941.2

The trainees on these courses were expected to follow exactly the same syllabus as they had on their Elementary Flying Training course, just more quickly because, while consolidating their flying skills on a new type, they also had to learn advanced skills, such as night flying. The Master was, therefore, an appropriately named aircraft. Pilots had to sharpen their instincts, refine their judgement and become more confident and precise in their decision making. A failure to do so may not just mean failing the course but could cost them their life.

Desmond went solo three days after his first flight in a Master and with just 4 hours’ training ‘on type’. His next flight was an introduction to low flying, which came with strict rules about what was and was not allowed. As they progressed, the temptation for trainees to ‘buzz’ or ‘beat up’ a building or ground feature by flying very low over it at speed could prove too much. If caught, it meant a court martial and potential dismissal, but if they misjudged their pass, the consequences could be fatal.

Despite the steady rate and tally of accidents on other courses around the same time, up to that point, in nearly six weeks of training, no one had been injured or killed on Desmond’s own course, but unfortunately this did not last. On 25 April, LAC Nelson entered a spin just after completing a turn. The aircraft crashed and caught fire, killing the pilot. This accident was found to be due to pilot error rather than a technical malfunction.3

Desmond progressed without incident and completed exercises in navigation, slow flying, instrument flying and aerobatics, before finishing his course at the end of April. He made no further notes on his progress through this course, in part because of the intensity of the training. On the days they were not flying, the student pilots were either in the classroom learning the theories and principles of the various aspects of flying or were in the Link Trainer undergoing simulator training. On 1 May, Desmond wrote of his success, ‘At last I am allowed to fly a fighter plane,’ and kept his eye on one of the Hurricanes attached to the training school.

In mid-1941, all trainee fighter pilots had to practise the manoeuvres in the Master, then learn to fly the Hurricane before they could fly a Spitfire because the RAF had no two-seat trainer versions of either the Spitfire or Hurricane. The Hurricane was almost as fast as a Spitfire, partly because it used the same Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 engine but was more forgiving thanks to its wider undercarriage. Its (mainly) wood and canvas airframe meant it could absorb damage and be returned to airworthiness more quickly, efficiently and cheaply than the more delicate and expensive Spitfire with its aluminium airframe and stressed metal panelling.

Desmond made his first solo flight in a Hurricane on 6 May 1941, then flew exercises in the Master, followed by the Hurricane, including night landings. After a further 15 hours and 10 minutes of flying over ten days, Desmond took his ‘wings test’, an intense flight with his instructor, Fg Off Nichols, that lasted 1 hour and 20 minutes. The flight, a practical airborne examination, included various scenarios, manoeuvres and emergencies to test the students’ decision-making skills as well as their flying ability. Desmond’s only note about this flight on 16 May was a single word: ‘Pass’. On 18 May, he flew again with the chief flying instructor (CFI), who agreed with Nichols’ assessment and also granted Desmond a ‘Pass’.

The instructors at Montrose had also judged Desmond’s character and suitability to squadron life. The RAF Volunteer Reserve, in which Desmond had enlisted, looked for leadership qualities among its pilots. Overwhelmingly, most of those who were commissioned as officers across the RAF Regular, Volunteer Reserve and Auxiliary branches had been to public school and/or were university educated, which Desmond was not.

There was a notorious snobbery that pervaded the senior officer ranks. They judged a candidate’s suitability for a commission, and their attitude towards ‘grammar school boys’, who were seen as cocky young men who did not know their place, meant those who were not recommended (the majority) became NCO pilots instead. As it strove to forge its own identity and prove its worth as an independent fighting arm, the RAF would become more meritocratic in time. Some of this progression was forced upon its squadrons as a result of the losses suffered during operations, but some of it was also rooted in the RAF’s experience overseas, where front-line conditions were very different from those in the UK. In the years ahead, Desmond would see those enlightened leaders promote men under them who had not just proven themselves in battle but could also lead others into battle. Given the choice between flying Spitfires or being an officer though, Desmond would have preferred to fly Spitfires.

The next few days left Desmond on a high. Aged 19, he graduated from advanced training and, although his proficiency as a pilot after a total of 118 hours basic and advanced training was still only marked as ‘average’, he was selected to fly Spitfires. He scribbled a simple hurried note in his logbook: ‘SPITs!’ His income almost doubled from 5s 6d as an LAC to 9s 6d as he was promoted through two ranks – senior aircraftman (SAC) and corporal – up to sergeant (service no. 1107760).

The fact aircrew started their operational flying careers with the rank of sergeant, irrespective of their length of service, caused some degree of consternation and friction with the other time-served sergeants in ground trades. The rationale stemmed from the belief that aircrew of sergeant rank or above would receive better treatment from the enemy if they were to end up as prisoners of war (PoWs).