Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

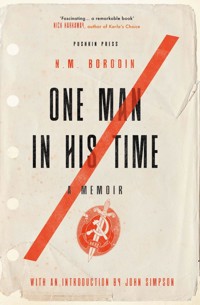

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

From humble origins, the eminent Russian scientist Nicholas Borodin forged a career in microbiology in the era of Stalin. Pragmatic and dedicated to his work, he accepted the Soviet regime, even working on several occasions with the Secret Police. But in 1948, while on a state-sponsored trip to the UK to report on the bulk manufacture of antibiotics, he could no longer ignore his rising consciousness of the suppression of independent thought in his country. It was then that he committed high treason by writing to the Soviet ambassador to renounce his citizenship.One Man in his Time is the story of a man trying to live an ordinary life in extraordinary times. Rich in incident and astonishing details, it charts Borodin's childhood during the revolution and famine through to his scientific career amidst the suspicion and violence of the purges. Unsparing and frank in its depiction of the author's collaboration with Soviet authorities, it offers unparalleled insight into the daily reality of life under totalitarian rule.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 643

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Contents

Introduction

This is a book like no other I have come across. Its simple title, bland byline (‘N. M. Borodin D. Sc.’) and opaque opening pages conceal the extraordinary story of a life-journey which leads Nikolai Michailovich Borodin from his origins in a peasant Cossack family under Tsar Nicholas II to the collapse of imperial rule and the Russian revolution, the starvation years of the Civil War, the terrifying growth of Stalin’s police state, the German invasion of Russia and Borodin’s emergence as a senior scientist entrusted with a hugely important mission abroad; and then to his decision to turn his back on the Soviet state, which he had come to detest, and defect to Britain at the end of the Second World War.

His experiences are dizzying and sometimes pretty scary. They are portrayed in a flat, unemotional style which nevertheless manages to capture the precise look of places and people: ‘Alekseev, the chief of the division of Armavir headquarters of the Political Police for the extermination of sabotage of the national economy was a man of middle height, in his late thirties, with watchful grey eyes… Only a few minutes before our first conversation started I saw an expression of a not very pleasant kind on his face. It happened that he had obviously forgotten he had appointed me to come and had ordered a guard to bring into his office a prisoner from the cellar under the building for a routine night interrogation. It also transpired that it was against the regulations of the place that arrested people should be seen by free citizens unless it was specially arranged; and Alekseev was very displeased. For a second there was confusion in the office, and then he ordered the guard to take away viiithe grey figure of a man of indefinite age whose lips were trembling as if he were ready to cry. We began our conversation as though nothing had happened.’

It’s often quite hard to work out whether you really like Borodin or not. Perhaps that’s because he’s so honest about himself and his thought-processes. Faced during the Stalinist Terror with a friend with a dodgy political record, Borodin runs through the possibilities: should he turn him away, or denounce him, or take him in and give him a job? He’s quite prepared to do the decent thing, but instead he chooses the bureaucratic option and shoves the decision off to a regional committee. None of it matters anyway, because the man simply vanishes.

Borodin’s frankness allows him to admit to reflections that you or I would probably want to suppress, in order not to show ourselves up. But he is a scientist, and a very good one: he examines his own motives in his political petri dish, and simply describes them for us. There is no posturing, no virtue-signalling; quite possibly no virtue. Or is it perhaps that he’s luxuriating in his new-found ability, as a political refugee in safe, non-judgemental Britain, to be absolutely honest, no matter how it might look to his new compatriots? He was told he had to work for what he calls the Political Police (we would call them the NKVD, or latterly the KGB and FSB, but they’re all basically the same thing) and did so reluctantly yet conscientiously: ‘I recorded with great care many cases I came across of intellectuals accused of sabotage or criminal wrecking. First I watched them with excitement and internal agitation but later I got so used to the picture that I was not troubled with any emotions and even businesslike accounts of the number of cartridges, disinfectants and protective clothes expended in mass executions did not produce any impression.’

The various cases he recorded are horribly fascinating: you can’t stop reading them even though you’d like to. Each case, inevitably, ends in execution—the head of the bacon factory who can’t give up the frank, confrontational ways of the Old Bolsheviks in these new Stalinist days ixwhen everyone has to watch what they say; the microbiologist who didn’t realise he was among informers when he said the Communists were worse than the Tsars; or Ishenko, the senior officer from the Political Police, who knew from experience how appalling the process of being executed was, and begs Borodin to give him a potassium cyanide capsule to help him die a quick death. Borodin reflects that things will be bad for himself if the poison is discovered, so he gives him a capsule containing pure soda. ‘I never saw Ishenko again,’ Borodin writes.

And yet we can’t help but sympathise with him when his mission to the US and Britain to obtain penicillin unrolls. It’s much too exciting to spoil by dropping hints, so I won’t go into any detail here—except to say that the man who sent him was Anastas Mikoyan, a comrade of Stalin’s from way back and one of the survivors of the bad days of the 1930s and 40s. Like Borodin, Mikoyan was obliged to do all sorts of terrible things, but he was basically a decent man who under other circumstances would probably have made a good politician.

For me, the question I was left with at the end of this extraordinary book was, how well would any of us behave if we were surrounded by a political system of pure evil like the one Stalin created? Borodin at least had the courage to defect, and the willpower to do what his conscience (what was left of it) told him he must do—escape to a system which was decent, free and open; a system where he could write and publish this blisteringly honest account of everything he’d done in possibly the worst half-century that any nation has been obliged to endure in human history. There but for the grace of God we and any other nation might find ourselves going.

john simpson,

Oxfordx

Foreword

“This out of all will remain—

They have lived and have tossed:

So much of the game will be gain,

Though the gold of the dice has been lost.”

Love of Life,jack london

The characters, names, incidents, events and places are genuine wherever they are given in this book, which has been written because the path I trod was vivid, full of interest and adventures. My fight for a career was also rich with impressions and exciting events. So much of the game remains to me as gain, “though the gold of the dice has been lost”.

I wrote this book in English which I have spoken only since 1945, nevertheless I like to use this tongue for thinking, speaking and writing equally well with my native Russian.

n. m. b.xii

Chapter One

Early Impressions and Experiences

“Have sent Natalie a goose. They say she is ill. Hell knows.”

These strange words I read long after they had been written by my great-grandfather in his diary, which recorded the daily happenings in his life for more than fifty years. Natalie was his daughter-in-law whom I knew as grand-aunt Natasha, a sickly woman overburdened with children. The diary was a collection of thick exercise books, their pages covered with his calligraphic handwriting and the records were laconic, some of them very emphatic.

My father, a country school teacher, died when I was too young even to be able to speak, but my great-grandfather I remember very well. He died in his eighty-seventh year when I was about seven.

I was always afraid of this old Don Cossack with his drooping moustache and unfriendly eyes set in a Mongolian type of face. Yet the old man was not unkind to me, and when I was sometimes taken to visit him by my granny I often received a sweet from him, but I was afraid to eat it. I was once told by my granny that he was a warrior and killed men. My grandmother was my first tutor and teacher who taught me to read and write.

There were many unusual things in the old man’s dark little cottage with its cold stone floors where he lived alone on his pension. Looking at the old sabres which were hanging on a wall, or at pikes in a corner, I often thought with horror that they were probably stained with human 2blood. Yet I was more frightened by the feeling that my granny, her sister and brothers were also afraid of their old father. The old man’s sons and daughters would always kiss his sturdy hand on coming to visit him or on taking their leave, and I had to do the same. There were many patriarchal traditions in the Cossack families to whom we belonged. My granny’s younger sister always addressed granny as “sister”, never calling her by her name, and granny in her turn would address her elder brother as “brother”.

I was taken to visit my great-grandfather one cold and rainy day, although I did not want to go. In the yard of his cottage were my granny’s brothers who stood silent, and as we approached them my granny knelt in front of her elder brother. “Brother, forgive my trespasses for Christ’s sake,” she said.

“God will forgive you,” was the reply. Then granny was addressed in the same manner by her younger brothers and they received the same answer. I was aghast as I watched them, and even missed the appearance of my great-grandfather at the cottage door. He supported himself on a sharp metal-tipped stick with a round silver head while his sons and daughter knelt asking forgiveness for their trespasses in the name of Christ. They all looked frightened of their old father, who remained for some time silent. Indeed I thought that he would not only refuse to forgive them, but would probably kill them with the sharp stick, and I was prepared to run away. Then abruptly the old man said, “God will forgive you, children of a bitch. I suppose, gentlefolk, you are chilled! Come in!” And so we entered the house.

On the way home I asked my grandmother what trespasses they had to forgive each other. She explained to me that it was the religious “day of forgiving” when everyone must ask forgiveness from their elders because one could always have done or said something wrong during the year.

I had many other opportunities of watching the methods of bringing up the younger generation in fear and respect for their elders.

3Once, passing the office of the local Cossack governor, whom the Cossacks called an “ataman”, I was attracted by what was going on in the big courtyard seen through the wide open gates. On a bench lay a man with his trousers pulled down. Two Cossack soldiers were sitting on the man’s shoulders and legs and a third was whipping him with a thick Cossack whip—“nagaika”—but no sound was heard from the victim. On another bench near were a group of old Cossacks sitting and smoking and watching the spectacle with obvious interest.

“Your son is a strong brave lad, Ivan Petrovich,” one old Cossack said to another, pointing his cigarette at the figure on the bench and spitting on the ground.

“He is all right,” Ivan Petrovich answered carelessly, “but he sometimes gets out of hand, the son of a bitch, and needs to be brought here to be whipped. I am too weak now to do it with my own hands…”

Then I saw the lad raise himself from the bench, pull up his trousers and bow in turn to his chastisers and to the group of old men, thanking all of them for “teaching him a lesson”. Then everybody laughed and the old man who had called him brave slapped his shoulder… “Never mind, my boy! One who has been beaten is worth two who have not. You are a real Cossack now, not a cissy. I suppose every lass from your street is dying to sleep with you, eh?” He laughed again and allowed the youth to finish the remainder of his cigarette. This was rolled with newspaper and resembled a small pipe with a long thin mouthpiece. It was called a “goat’s leg”.

These words were really high praise for the young man, and it was not considered bad for a girl’s reputation to sleep with her boy friend. It was very common for mature boys and girls from peasant families to sleep together after they all gathered outside during the long summer evenings. These gatherings were called “evenings” or “streets”. First the young people would sing and dance and then couples would go away to sleep in haylofts or sheds. The lovers often married, but sometimes they parted and each of them found a new partner to sleep with, and it was 4considered quite normal to marry a girl who had slept before with several young men. Their parents had behaved in the same way when they were young and it was said that a clever girl would never forget herself. They called this love-making “matching”.

In boyhood I learned the superstitions of my folk. The eves of Christmas, New Year and the Day of Baptism, in particular, were full of excitement, for during the night the evil Power of Hell was abroad. Crosses were marked with chalk or charcoal on window-shutters and doors before darkness fell to prevent evil spirits from entering the houses, and during the evening people would attempt to divine their fates. It was very simple. One had to pour the melted wax of Church candles into cold water where it produced peculiar shapes which cast mysterious shadows if held between a lighted candle and a wall. People would claim that they saw in these shadows exactly what would happen to them in the future. The candles, however, had to be lit for a short time in front of an icon and then snuffed out by turning them over. Without this the divining could not be true.

There was another way to cast fortune—by making shadows on a wall. It could be done by using crushed burned paper, but to get the correct results one had to burn pages of the Scriptures. This was considered too “black”, and only a few daring souls used such a method. One could also see one’s fate in a mirror, also in a wedding-ring, which was placed in a glass full of water. One had to be alone and look at the ring or the mirror for a long time, in the light of three candles, starting at midnight.

The bravest people went out at the stroke of midnight to the deserted crossroads where they threw to the four parts of the world the crumbs of their eve’s supper, asking the evil ones that wandered in the darkness what the future held for them. Their crosses had to be taken from their necks and left behind. The widow of the blacksmith Ustinov told me that her husband went out at midnight on the eve of the Day of Baptism to ask his destiny at the crossroads and came back “without his mind” and with his face as white as the snow on the roads. He told his wife 5that when he had thrown away the crumbs there immediately appeared from nowhere a swarm of black dogs with eyes like red hot coals. They surrounded him and began to whine as dogs sometimes do when they scent a dead body. The blacksmith, with all his strength, could not beat them off and fell unconscious in the snow. When he revived, the dogs had gone but Ustinov understood that it was a sign to him to be ready to depart from this temporary life to the eternal. His wife said that within three months her husband “dried up” and then died. Often, too, the wife of the miner Kudlatov would tell me that she saw in a wedding-ring her husband’s face and signs of their happy married life long before she met her husband.

When my great-grandfather died and was taken to a cemetery the floor of his cottage was immediately brushed and the dust was buried in the yard. My grand-uncle told me that this was necessary to prevent the corpse from coming back in the night from its grave. This explanation terrified me and on discovering a corner which was not very well brushed I cleaned it energetically, carefully collecting all the dust and burying it outside.

The holy water and holy oil from the lamp placed in front of the icons were useful medicines. The holy water could be drunk but the holy oil was always rubbed into one’s skin as a remedy for colds and coughs. Sometimes the holy water was considered not “strong” enough and it would be necessary to “whisper” over it. There were very many people who were specialists at “whispering”. Some, however, desired to cure their external as well as internal illnesses with something chemically stronger than water. Our neighbour, old man Sapogov, who was a cobbler, would cure himself with kerosene which he used externally and internally throughout his life and apparently with great benefit to his health. He carried in his pocket a small bottle of this medicine because he had a permanent cough. When I had a cough one winter Sapogov gave me a few drops of kerosene in water and my coughing stopped immediately. After this I decided to use kerosene myself and searched for a bottle in the 6larder but was prevented by my grandmother, who said I was too young for such medicine. I learned also that the best way to help a woman in heavy labour was to open wide the King’s Gates to the altar in Church. One night the wife of a shop-assistant, Sasonov, who lived near, was in great pain because she could not deliver her child in spite of the skill of a midwife. Her husband was advised to ask our parish priest to open the King’s Gates. When Sasonov came home he was told that his wife had given birth to a healthy baby.

Out of the unknown would sometimes appear… The Sight. Only a few had the power to see it and of these my granny was one. One evening someone knocked on the door of our cottage. Granny thought it was either my mother or myself because we were both out, but it was her brother who lived very far from our home and was dangerously ill at that time. My granny asked him in but the old man did not answer, turning and walking away. When my mother and I came home granny told us that she saw “The Sight” of her brother and that he would undoubtedly die. Next morning my grand-aunt came to tell us that her husband was dead and they established the fact that he died at the same time that my granny saw him on the doorstep. My grandmother foresaw many things in her life, she also saw her own doom and foretold her own death.

These people of Russia, when I was a boy, had a dual faith to which they gave equal credence. They believed in these things and also in the Christian faith as it was established by the Russian Orthodox Church. Their code of ethics was high, there were almost no thefts, either in the town or in the surrounding miners’ settlements, and yet there were always a lot of newcomers to the mines. I remember no murders in my home town or in the district and saw no man killed before the Civil War.

My early memories of religion are of my first confession, followed by Holy Communion. Once a year, before Easter, everyone had to fast and to visit Church every day for a week. This was called “govenie”. Then one made a secret confession before a priest, after which one was allowed to take Holy Communion. The latter, however, was dependent 7on one’s sins, for some of which it was necessary to pray and fast longer.

It was said that a pupil of an advanced class at a theological school, who confessed to adultery, was not allowed to take Holy Communion for a few weeks, after which the priest had to decide whether he could pardon this unforgivable sin. The boy became thin and pale, not because of fasting or because he was very conscience-stricken, but simply because he was the only one in his class who was not allowed to take Holy Communion. His friends regarded him as though he had committed murder or theft, and they avoided him. The despairing boy decided as a last resort to see the Archbishop, who was the rector of the school.

“What is your sin, my boy?” the Archbishop asked him and the sinner explained.

“I don’t see why the sin is unforgivable, my boy,” said the Archbishop.

“But Father Alexander said that it was, and he would not absolve my sin…”

Father Alexander and the Archbishop were not on very good terms and the boy knew it.

“I suppose Father Alexander does not understand these matters very well,” said the Archbishop as he put his hand on the boy’s head. “By the Power which I was given by God, I His humble priest, forgive and absolve thy sins in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.”

To me, at ten years of age, my sins seemed much worse than adultery. The summer before I had twice eaten cherries which were hanging over the wall from our neighbour’s garden and then… those pears! But I knew that my worst sin was that quite a few times I had secretly smoked my granny’s tobacco.

“What is thy name, boy?” I was asked by the priest to whom I came to confess my sins. “Nikolai,” I stammered. I already saw in the priest’s eyes that he would not absolve my sins.

“Confess thy sins, slave of God, Nikolai,” was the severe command, and it seemed that ages passed before I felt the priest’s warm hand kindly 8stroking the top of my head and the incense wafted from the epitrachelion over me as I heard, “By the Power which I was given by God…”

On entering a gymnasium, or secondary school, when I was eleven, I was told by my mother that unless I gained a scholarship she, on her salary of a working woman, could not afford to give me the education I wanted. I eventually did get the scholarship, but the horrible shadow of being cut off from education was always before my eyes.

A group of my school fellows were one day talking to a gymnasium tutor about their future university education and I was careless enough to say that I wanted to be a scientist.

“You had better think how to be a good shop-assistant. You have not enough money to afford a university education,” the tutor retorted and the boys laughed at my confusion. Remembering that incident I think the tutor was not a very scholarly-minded person, but at the time I was infuriated and would have set fire to any rich house if I had been convinced that it would give me any help.

Each day in the school started with a roll-call and a morning prayer. There were forty-two boys in my class at the State Gymnasium in Kamensk, a small country town on the river Donetz in the South of Russia. There were eight secondary schools at that time in this small town which only recently had been a large Cossack village.

The roll-call went on. “Avdugin?” “Here!” Avdugin’s bass voice sounded from the back of the hall. Like the majority of the boys in the first class he was about my age but looked rather older. Because he was a tall, slim, good-looking boy with a dark skin and shiny dark brown eyes his name was “Gypsy”.

“Alferov?” “Here!” answered a pock-marked, short, ginger boy whom we called “Ginger red”.

“Artemiev?” “Here!”

“Berdnikov?” “Here!”

“Besedin?” “Here!” squeaked the pale and lean “Persian Perfume”. He was unfortunately allergic to washing his feet.

9“Borodin?” “Here!” My nickname was “The Beard”, not because I had any hint of a growth of hair on my face. The root of the word “beard” is part of my name.

There was no chapel in our school and morning prayers and roll-calls were always held in the large school hall. A pupil was appointed to read a selected chapter from the Gospel in Old Slavonic and one morning this honour fell to a boy from my class. His name was Buchinsky, a funny little boy with a small snub nose set in a face rather like a pudding, but he had the manners of a very important man. His family was well-to-do and tried hard to reproduce the airs and graces of the Russian aristocracy. To appear at his best Buchinsky read the Gospel with the fashionable accent then employed by “the golden youth” of St. Petersburg’s salons. Our school priest, Father Andrei, was greatly astonished to hear such reading and turning round he looked over his spectacles at little Buchinsky.

“In what language are you reading the Scriptures?” he demanded. “In Old Slavonic,” the confused boy stuttered.

“Read it over again, and properly. One must have a proper fear of God and not be monkeyish while reading the Scriptures.” After that, Buchinsky’s nickname was “monkey”.

The summer sport of boys like myself was swimming in the river and here I spent a great part of my summer vacations. With my schoolmates I played Red Indians and I suppose our sunburnt bodies were not very much different from them in colour. The river was deep and sometimes people drowned. My old granny was always afraid that the same would happen to me. “If you are drowned, do not come home,” the simple dear one would scold.

In autumn and winter we would skate on the river but school hours were long and there were always tasks to be done at home. Then my leisure hours were devoted to reading and to my personal hobby, which was solving mathematical problems. I loved these long winter evenings, in the cosy light of the kerosene lamp.

10The half-military discipline at the school was strict, but we sometimes defied it. This frequently happened at the lessons of the Latin teacher. His name was Sergei Vassilievich but he was known among us as “Gaudeamus”.

There was something pathetic about this little old man who would peer at us through his gold-rimmed spectacles as he told us about his student life and how happy he had been. Remembering those golden days his face would change, his eyes shine and he would sing to us “Gaudeamus Igitur”, and teach us to sing it. His methods of teaching also were a little quaint. He taught us for instance that the best way to learn conjugations of Latin verbs was to sing them and we did so heartily, but I am not quite sure that it helped.

We once played a joke on “Gaudeamus”. When the old man came to give us his lesson all the class was singing in chorus a song we had composed, using Latin prepositions as if they were funny names of people or songs and dances.

“‘A’, ‘ab’, ‘e’, ‘ex’ and ‘de’,” we sang, “‘cum’ and ‘sine’; ‘pro’ and ‘pre’.”

“What is going on here?” asked “Gaudeamus” in astonishment.

“‘A’, ‘ab’, ‘e’, ‘ex’ and ‘de’,” we answered in chorus.

“Stop it immediately.”

“‘Cum’ and ‘sine’,” we yelled defiantly.

“You have gone mad, I am going to report you to the headmaster!”

“‘Pro’ and ‘pre’,” the class roared.

But old “Gaudeamus” did not go to the headmaster. He sat down at his desk, dropped his head on his arms and we understood that he was soundlessly crying as a very helpless old man sometimes cries.

After that we swore to behave at his lessons and to be well prepared for them. We vowed that anybody who failed to do this would be secretly beaten, after being captured in the cloakroom and covered with overcoats so that he could not recognise his executioners. This was a usual “capital punishment”. As far as I remember, however, we all kept the oath of honour and nobody was beaten.

11Our teacher of Russian language was Ivan Vassilievich Savin. He was a shortsighted man and always wore a stiff teacher’s uniform which gave the impression of a hard shell. His eyes were protuberant and looked through the strong lenses of his pince-nez as if they were out of their orbits. We called him “Crayfish”. He was a good teacher, but not quite just. He selected a few favourites from our class and a few whom he disliked. The former, of course, always gained good marks and the latter very few, independent of how they were prepared for his lesson. “Persian Perfume” was unfortunate enough to be amongst the number he disliked and once when he brought home bad marks his father, a Cossack peasant who was paying hard-earned money for his son’s education, whipped poor “Persian Perfume” with the horse reins, after which the poor boy could not sit down comfortably for a week.

For the teacher’s birthday we prepared a present. When “Crayfish” attended that day for a lesson we wished him a happy birthday and at the same time the school caretaker appeared carrying a huge cake box which was tied with a gay ribbon. For this solemn occasion the caretaker had put on his best suit and had oiled his hair and beard, which he would normally do only on Saturdays when attending Church. “Crayfish” was touched and flattered by our attention. The glowing teacher opened the box and peered in. Suddenly we saw him stiffen, then angrily turn to the caretaker who, in his turn, became paralysed when he saw the contents of the box. We held our breath as we waited.

“What is it?” the teacher demanded.

“It is a crayfish, sir,” stuttered the caretaker. As we knew only too well, the box contained the largest boiled crayfish we had been able to get, its fishy eyes glaring through a “pince-nez” made from wire. On a piece of white cardboard was written a “poem” about the injustice of the teacher, who on reading it, shot out of the room like a cork from a champagne bottle, followed by the confused caretaker carrying the huge crayfish in his hand. For this present the whole class was punished, but “Crayfish” never dared to be unjust again.

12The first years of the First World War saw a blaze of patriotism, and trophies, such as German helmets and bayonets, were in great demand among us schoolboys. For one German bayonet I exchanged twelve sandwiches, but on investigating the treasure I found that it was of French origin. Being very disappointed I demanded the return of my sandwiches but they had already been eaten. To console me the boy with whom I had made the exchange told me a long story that the bayonet had been captured from the French by the Germans, and from the latter by our soldiers. He also swore that he had been offered fourteen sandwiches for the bayonet but let me have it because he liked me. This I doubted.

Some boys in the more advanced classes joined the fighting Russian troops as volunteers. One morning Gypsy Avdugin did not attend his lessons as usual and it was said that he had also run away to the front to join our troops as a volunteer. I was particularly upset because we had agreed to run away to the front together as soon as I had collected some money for the journey. But next morning a confused Avdugin entered the class with the headmaster Bogaevsky who told us that Avdugin had been “captured” by the police at the nearest railway station and brought home.

We expected a storm from the headmaster but he said that he would give us a lesson in history, on the subject of the famous Roman warrior, Caligula. Bogaevsky was not only the head of our school but a teacher of history and an excellent speaker, who could keep the attention of his pupils throughout his lessons. “You can see now,” he concluded his lesson, “that when Caligula was a boy-soldier his militant appearance produced an impression even on the severe Roman soldiers, who were touched on seeing the little boy wearing ‘caligas’—the heavy soldiers’ shoes. Do not forget, however, what a monster Caligula became after his early military experience. Wars by their horrible manslaughter, corrupt even the minds of mature people, and you schoolboys would give better service to your country and to all mankind by attending normally to your lessons and by trying to be very human people in the future…” After this there were no more attempts to run away to the front, but soon the war came to us.

13Life was growing daily harder. Commodities of the first necessity became a luxury. Sugar was almost impossible to get, and the main meals in our family consisted mostly of porridge or of boiled potatoes with vegetable oil. Other foods were either too expensive or were unobtainable. On the other hand, one could see large posters in the streets, with the slogan “The War Until The Victorious End”.

“To the devil with your war,” I often heard at the homes of my relatives and friends, and by “your war” they meant the war of the Tsar and his government who were daily becoming more and more unpopular. The people were half openly saying that the Tsar was a drunkard, that the Tsarina was corrupt and a German spy and that the Court ministers appointed by the Tsar were selling Russia to the Germans.

One day the keeper of a local stationery shop appeared at the gymnasium. Textbooks, copybooks, pencils and other articles of this kind had become very scarce, but the shop had a large stock of pictures of the Tsar and his son bearing the familiar slogan, “The War Until The Victorious End”.

The little shopkeeper was sure that everyone would like to possess such a poster. It seemed, however, that business was not very good and he left a free poster in the corridor with the legend “Every schoolboy will be glad to hang in his room the picture of our beloved Emperor and his son and heir in their military uniforms”. Below this was given the address of the shop and the price of the picture. Next morning we saw that someone had pasted over the words “the picture of” with a strip of white paper.

There was even something wrong with the water which flowed very slowly from the tap in our yard, and it was said that the pump station was short of fuel. Our little house shared a yard and garden with a big two-storied house with a verandah, owned by a colonel who held a post in the office of the local governor, and both houses were supplied with water by the same tap. Water was carried to the colonel’s house by his batman or maid, and granny drew water for our household. The colonel 14was called in our family a “bloodsucker”. This was not because of his red face and short apoplectic neck, but because he sometimes brutally beat his two batmen. This he did on the verandah, slapping the faces of the batmen with his heavy hand as they stood stiffly to attention. Granny often said that the time would come when the batmen would pluck out their master’s soul.

One day the water flowed slower than ever and a long line of buckets was placed beside the water tap. The first few were ours, the others from the colonel’s house. The colonel sent out his maid to put our buckets at the end of the line as he wanted a bath, but my granny protested and immediately placed our buckets to the front. The maid reported this to her master who dashed out on to the verandah shouting a string of oaths so foul that even the miners would not utter them when they had been drinking and fighting. That evening I swore that I would personally help the batmen to pluck out the colonel’s soul when the time came. In my imagination I guillotined the colonel and laughed when the blood spurted from his neck. I had already read something about the French Revolution and it excited me greatly.

It was a surprise one morning to pray before lessons, not in the large hall but each class separately, and the rumour spread that someone had thrown red ink on the Emperor’s picture in the hall. It appeared to be the truth and when we were allowed to enter the hall the large frame was empty, but there were no investigations about the hands which had spoilt the picture and this also was unusual. We were told that the picture would be replaced in a week, but this did not happen.

One day there were endless speeches in the streets and a great number of pamphlets were distributed to the people, who were all singing the “Marseillaise” and “We fell as victims in the fatal struggle”. All the Tsar’s pictures were burned or torn. It was 1917 and the February Revolution.

The summer vacation of 1917 I spent in a village near the small town Shackty, which is in the centre of the Donetz Basin mines and near 15Kamensk, my home town. I went to stay at the home of a young teacher whose name was Borisov, a handsome fellow without family. He was a bee-keeper and very active in politics. In exchange for my help with the bees, in which I was also interested, Borisov was to keep me during the vacation.

I did not know exactly where Borisov’s house was situated and on arriving at the village I enquired where he lived. My informer was a middle-aged peasant with a stick, who looked at me suspiciously.

“What? the house of the rake who is spoiling all our lasses? Go straight up to the Church and then turn…”

“No, I don’t want the rake’s house,” I interrupted the peasant, “I want Borisov’s.”

“I am telling you about Borisov. Turn right as I said and you will see the school.”

It seemed that Borisov had the reputation of being a rake, because he was giving public lectures to the village youth advocating the freedom of sexual relations. I never attended these lectures because I was too young to be interested, but I remember that on an occasion the teacher’s gates were smeared with tar. It had been done during the night and meant that the person living behind the gates was considered a bad character from a moral point of view.

Borisov would often tell me that the time would come when the poor of the village would pluck out the beards of the rich, and he would also say that the Revolution had still not developed far enough and that the people were still being deceived by the rich, who were anxious to continue the war with Germany in order to amass more money.

“Look who are in our revolutionary administration posts! Exactly the same people who were in power before the Revolution. Has the poor peasant got his land? No! Have the miners got the right to control their mines? No! We must sweep the vermin away. We must destroy them with everything that belongs to them and on these ruins we shall build the Republic of the Poor.”

16Others said the same, mostly young peasants and miners who often visited the teacher’s house. They would sing “Arise ye wretches of the Earth”, and taught me to sing it. It sounded exciting and was called the “Internationale”. These young people called themselves Bolsheviks. I must confess that at the time I understood nothing of what was going on, but what I was told seemed very attractive as they formulated their vague dreams about a happier life.

The miners in the surrounding district lived very wretchedly. I was sent one day by the teacher to a market in Shackty to exchange some honey for nails which we needed for the apiary, and I stayed the night with a miner’s family who were friends of Borisov. Everything was black in this mining settlement, even in summer. The mud in the streets was black like liquid soot after a downpour of rain, and so deep and sticky that not only passers-by, but even horses, could hardly pull their feet out of it. The faces of the people and their children were also black because there was no soap. They lived in small and primitive huts infested with vermin. Food was very scarce because one had to exchange articles with the local peasants in return for food, and whilst I was there the family with whom I stayed ate only potatoes. The housewife complained that the potatoes “made holes in their navels and were coming out” because they were so weary of the monotonous fare.

Next day, my host and I attended a miners’ meeting. There were crowds of miners listening to the fiery speakers, who addressed them from a wooden platform. I did not understand all that they said, but one speaker attracted my attention because he stood out from the grimy crowd around him. He wore a shiny bowler hat, his plump body was clothed in a clean smart suit and his pomaded moustache was stiffened like a corkscrew. My companion told me that the man was a lawyer and the chairman of the local revolutionary committee. The lawyer spoke very well and his audience listened with attention, but when he said, “Everybody must be ready for further sacrifices in the name of the immortal ideals of the Revolution and in the name of our victory in the war with Germany”, 17the mood of the crowd changed. On to the speaker’s platform jumped a miner, his face black with coal dust. “Smell that!” he cried, shaking his fist under the nose of the speaker. “We want none of your ideals and your war to…!” There followed the recommended place of destination in very strong and colourful words.

“Right! Down to hell with this fat belly!” shouted the crowd, and the meeting broke up amidst pandemonium.

The teacher was a good bee-keeper. He had about thirty hives and there was always plenty to do. While working at the apiary I veiled my face and tied the bottoms of my sleeves and trousers to prevent the bees crawling in, but Borisov never did this. He would say that the bees knew him and I believe that they did.

As we were separating a new swarm one morning, Borisov suddenly gave the most inhuman scream. He threw a heavy smoker into an opened beehive and, jumping like an antelope, he disappeared from the apiary. A few seconds later I heard the splashing of water and what sounded like the roaring of a lion. I hurried to find out what had happened and on turning the corner of the house I could just see the top of the teacher’s head. The rest of him was immersed in a large barrel filled with rainwater. He had been badly stung by a bee and after that I worked in the apiary alone for a month. The part of his body that had been stung gave reason to the old people in the village to say that it was God’s penalty to the rake for his immoral life.

The time between the February Revolution and the October Bolshevik Revolution passed quickly away and the shots of the first battles of the Civil War were heard in the streets of my home town Kamensk. These shots were exchanged between the Reds and the Whites and all the population of the town, like the population of all Russia, was split into those who sympathised with the Reds, with the Whites, or who were “neutrals”.

The last named were inactive, but they always called one of the fighting parties “ours”. Indeed it was impossible to be neutral, because each 18family had relatives and friends who were fighting on one or the other side in the Civil War.

In our family, “ours” were the Reds. Their slogans were simple and comprehensive. They said that they were fighting for peace, daily bread for all, land for the peasants and factories for the workers, and for government of the country by the people to produce material blessings. The Reds also said that they were the last army in the world and as soon as they had defeated the Whites there would be no more armies and wars. They hated army titles, ranks and epaulets. Their chiefs were called “Comrade Commanders”.

The slogans of the Whites said nothing about peace, bread for all, land for the peasants and factories for the workers, but they did say that the war with the Germans must be continued until the victorious end. They promised that in the future Russia would be ruled by a parliament. No one, however, sincerely wanted to continue the war with the Germans, not even many of the Whites themselves, and the promise of a parliament called forth no enthusiasm. There had never been a parliament in Russia before and for the people the word had an empty sound. The Whites still clung to the Tsarist army uniform and they had the same titles and ranks as before the Revolution.

Colonel “Bloodsucker” was White, but so was our headmaster, Bogaevsky, the great teacher of history who was admired by all his pupils in the gymnasium, and whose wonderful speeches about the independent State of the Don Cossacks had won him the title of “The Don Accordion”. Another of our teachers, Gorobtsov, was Red. The pupils of our school were also split up into White and Red and neutral, just as their elders were at home.

The laws of the Civil War were hard, and pity played no part in them. During the mass exterminations of the members of the opposite camp both sides were guided more by emotions and hatred than by reason. Denunciations became a deadly weapon and a very convenient one for people who were too fastidious to dirty their own hands with the blood 19of their personal enemies. Both fighting camps encouraged denunciations and eagerly shot down the “enemies” who were pointed out to them by the finger of a “loyalist”.

The Reds shot our headmaster Bogaevsky dead, because he was White. The Whites hanged the teacher Gorobtsov because he was Red. The Reds shot my schoolmate Obukov and his six-year-old sister, because they sympathised with the Whites. The Whites shot the boy Soloviev and his old mother, because they sympathised with the Reds. Our school no longer existed. The teachers and pupils were either fighting or helping one or other of the sides, and many of them had been killed, some by stray bullets during street fighting.

There were a great many of these bullets flying about when the battles became very heated, and the people called them “bees.” It was a strange coincidence that both “Crayfish” and “Persian Perfume” were killed by “bees” in the main street of the town. Nobody knew whether they died on the same day, because there were always a lot of corpses lying in the streets for quite a few days before they were removed. “Crayfish” was lying on his back. His face bore a solemn expression and he no longer reminded me of a crayfish. “Persian Perfume” was pathetically curled up like a thin kitten, with a bullet in his right eye.

As always each fighting camp cried out against the monstrous brutalities of its enemies and called for revenge. This on the principle of two eyes for an eye and two teeth for a tooth.

One day the rebellious Red Cossacks with the Red Guard miners pulled out the local governor—the ataman—from his house and slashed him with sabres in the street, with several captured White officers. Colonel “Bloodsucker” was amongst them. The officers died hard. One of them, a handsome, tall, strong man with black hair and a haughty face, tried to cover his head with his arms, but his wrists were slashed in two. Lying with his face on the ground the officer screamed, moving his arms with the severed wrists as if he was swimming in the mixture of his blood and the road’s dust. The ataman was sitting with his back supported by 20the leaning fence of a garden in front of his house. He pressed his large hands with outstretched thick fingers to his slashed chest as if he would prevent his soul from leaving his mutilated body. His eyes in his pale face with the thick moustache were wide open. Tears were running from them like streams, and dripping from his moustache. Colonel “Bloodsucker’s” face was a mass of bloody flesh, his mouth had been slashed by a slanting stroke and it produced the impression of a horrible smile. One of the Cossacks swore, “so you are smiling, son of a bitch” and brutally struck him with the butt end of his rifle. After this blow, the colonel began to snore like a horse.

“Finish them off,” cried one of the crowd.

The reply came: “Shut up, you dirty dog! Do you want to get the same punishment? They will cough until they have coughed out all the blood they drank from us. Understand?”

When the Whites entered the town soon after this incident they shot every fifth man from the captured rebellious Cossacks and the Red Guard miners. The others were scourged. The captured men numbered about two hundred, but some of them died soon afterwards and were buried in a common grave on the outskirts of the town. They died because their genitals were gradually screwed with wire to compel them to give up their leaders. Their corpses had dark blue faces.

A crowd gathered to watch the execution of the condemned men. The morning was chilly and there were small pools on the wet ground. The common grave was already dug by the condemned men themselves. It was long like a trench but not very wide or deep. After the first layer of soil there was bright yellow clay, and a heap of it rested on the other side of the grave. It was sticky and heavy after the rain, and here and there was a trickle of yellow water running down into the grave.

There was unusual silence only broken by discharges from the rifles of the firing squad. It seemed as though both the executioners and the condemned were obliged to carry out some dirty and tiresome work and hurried to finish it as soon as possible. When their turn came, each 21condemned man quickly undressed, as soldiers do, and having put their folded clothes aside walked in their worn-out dirty underwear to their last resting place, trying not to step into the cold rain-pools with their bare feet. At the edge of the grave some of them were whispering and nobody knew whether it was their last oath or their last prayer. Some crossed themselves with the orthodox cross, then all quickly disappeared into the grave.

When the execution was over, the grave was covered with the clay, and the next day the arms and legs of the executed men could be seen and some of them moved feebly. It was said that some people in the neighbourhood pulled out a wounded man from the grave and tried to save him, but others denounced them and the Whites came and shot everyone who was mixed up in the matter, including the man from the grave.

The scourging of the rest of the captured men came three or four days later. It was carried out in the courtyard of the former governor’s office, where the old Cossacks used sometimes to bring their wayward sons to teach them a lesson with the help of the Cossacks’ whips. Now the beaten men did not thank their chastisers. They were not whipped with the “nagaika”, but scourged with the thick metal rods which were used for cleaning rifles. After a few blows of the rods the backs of the scourged men were like chopped meat and at the end of the beating each of the punished men was carried away from the bench either unconscious or dead.

There were many common and single graves of unknown people scattered about the town. During the firing intervals, I once or twice saw an unknown priest praying at the graves with groups of people, “for the peaceful rest of our perished brethren, the names of whom only Thou, O Lord, knoweth”. But then the priest disappeared and it was said that he had been denounced to the Reds for his sympathies with the Whites, and he was shot dead.

There were inscriptions over some graves and two of them remain in my memory. Both inscriptions were nailed to their unpainted wooden 22crosses which were only a few yards from each other. The first inscription was on a small sheet of thin rusted iron. It was written neatly with black oil paint… “The Colonel of the shock-officers’ Regiment Ksenofont Pavlovich Palladin. Killed in action defending against the Red bandits, the Great and Indivisible Russia. O Lord, let him rest in peace.” The other was written with tar on a wooden board. The letters were rough and there were mistakes in the spelling. It said… “Stepan Kovalev. Miner and Red Guard. Fell for Communism in the battle against the White bandits. O Lord, let him rest in peace.”

During a lull in the fighting between the advancing Reds and the retreating Whites, my two friends Grisha and Maxim and I made what we called “military reconnaissances”. During these reconnaissances we always collected a great number of cartridges, rifles and other arms which we could hide in a room in the town’s bank, at the corner of the main street, Donetz Prospect, and Starovoksalnaia Street. In the past the bank was a beautiful white two-storied building with large windows, heavy polished doors of dark oak and shiny brass handles on the doors. Now it was half destroyed and dirty and the dark emptiness of its windows and doors gaped like the eye holes of a skull. We considered our hunting for arms a very exciting sport and we gave the booty to Grisha’s father and Maxim’s uncle, who were Red Guards. They sometimes appeared in the town when it was taken by the Reds. Grisha was a year my senior and Maxim two years younger. Before the Civil War, Grisha studied at the handicraft school and was very clever with his hands. His father was a cobbler. Maxim had studied before the Revolution only in an elementary school. His mother was a widow and worked as a typist. The bold tall Grisha was the leader of our band. I was his lieutenant and short fat Maxim was called “supply column” because he always carried bread in his trouser pockets.

After taking arms one day to Grisha’s father who was a very strict man, we were told that if we continued to reconnoitre he would take off two skins from each of us the next time he came back, and we promised 23not to hunt for arms again. Our adventures, however, were too tempting, so that even the vague fear of death and the concrete fear of losing two skins could not prevent us setting off again.

Once again, we set out on our hunt. The streets were quiet. There were many corpses about but no flying bullets and only very far away two machine guns rattled.

“They are Maxims,” said Maxim nodding his head to where we heard the rattling of the guns. He was very proud that he had the same name as the machine guns.

Our destination was the small railway station—North Donetz—which was only two or three miles from Kamensk station. There were often a great number of abandoned railway trucks at North Donetz during the intervals when neither side was in power, and these carriages were loaded with the arms that we were hunting for.

That morning the station was empty as always after battles. Here and there were corpses and we saw at once that there were many locked and unlocked trucks, and even a full train of chained cargo trucks with an engine at its head. It was very tempting to investigate the cargo at once, but we decided to have a rest and some of Maxim’s bread and sat down on the ground near the railway station in the shelter of an overturned truck.

“Listen, the Maxims are getting nearer,” Maxim said. The rattling of machine guns was getting much louder as though they were moving and calling each other to meet at the station.

“Let us investigate the train and start our hunt,” Grisha ordered.

Here we found real treasure. Some trucks were loaded with rifles packed in cases, some contained cases of hand grenades, revolvers, cartridges and heaps of tapes fitted with cartridges for machine guns. Our eyes were darting about in excitement and we forgot about the firing moving nearer to the station. When we had finished plundering we looked exactly like Red Guards. Our chests and our waists were crossed with machine gun tapes. From each belt were hanging a couple of loaded 24revolvers and a few Russian hand grenades which were called “bottles” because of their shape. In addition to this, each of us carried a rifle.

“It is a nice haul but a bit too heavy to carry,” sighed Maxim. He was shorter than his rifle and looked very funny.

“Be a strong man, Maxim,” Grisha and I both laughed at him.

“Look, the bees,” Grisha cried, and then we heard the machine guns firing a very short distance from the station. The “bees” sometimes pierced the sides of the trucks, the station was under fire from both sides. A wonderful idea came to Grisha.

“Listen, pals, it is much safer to stay here than to go back. Here we are in the shelter of the buildings and trucks. Let us see what happens and then decide what to do. But while we are here we should do something to prevent the Whites taking the train away.”

“But how could we?” exclaimed Maxim and myself.

Grisha’s eyes were shining with triumph. “It’s very simple. There are plenty of cases with grenades. We will put some of them in the engine cabin and others under its wheels, then we shall throw two grenades, one into the cabin and another to…”

“But the Whites could bring another locomotive from the station Lickaia…” I interrupted.

“They would never dare, it would take too long. I am sure the Reds will be here soon. But anyhow let us take the risk.”

We liked the idea very much if only for the fun of blowing up an engine.

“We must cast lots as to who will throw the grenades, mustn’t we? If not, I shall not take part,” Maxim said, his voice trembling. He was afraid we would not let him, as the youngest, take an active part in the exploding.

We worked quickly. The heavy case with grenades was placed in the cabin near the pipings and gauges, the other one we put next to the back wheels of the engine. We were so absorbed in our work that we forgot everything in the world as we hotly discussed whether one case of grenades would be enough to damage the big wheels.

25“Get those——! Drag them to the buildings. If you Hell bastards let out any cry you are finished…!”

Everything occurred so suddenly that I understood what had happened only after all three of us were crouching with our backs close to the station building. Our hands and feet were bound tightly with the machine gun tapes we were wearing. There were five men who had captured us. They wore shoulder tapes and on their sleeves they had badges of a skull and cross bones. One man bore the insignia, officer. They were Whites, and from a detachment that did not take prisoners.

“Where are the Reds? Who sent you to explode the train? Will you answer you… or shall we kick out your brains, you bloody bastards…?” The questions were accompanied by kicks on our faces and chests. Maxim began to cry.

“Shut up you——!” and Maxim spat out blood. But what could we tell the soldiers? Had we wanted to, we could have said nothing.