Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

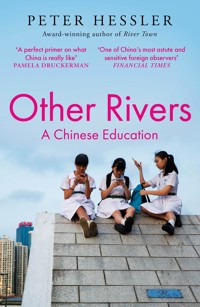

'Memorable... One of [China's] most astute and sensitive foreign observers' Financial Times 'Compassionate... full of warmth' Guardian More than twenty years after teaching English to China's first boom generation at a small college in Sichuan Province, Peter Hessler returned to teach the next generation. At the same time, Hessler's twin daughters became the only Westerners in a student body of about two thousand in their local primary school. Through reconnecting with his previous students now in their forties - members of China's "Reform generation" - and teaching his current undergraduates, Hessler is able to tell an intimately unique story about China's incredible transformation over the past quarter-century. In the late 1990s, almost all of Hessler's students were the first of their families to enrol in higher education, sons and daughters of subsistence farmers who could offer little guidance as their children entered a brand-new world. By 2019, when Hessler arrived at Sichuan University, he found a very different China and a new kind of student - an only child whose schooling was the object of intense focus from a much more ambitious and sophisticated cohort of parents. Hessler's new students have a sense of irony about the regime but mostly navigate its restrictions with equanimity, and embrace the astonishing new opportunities China's boom affords. But the pressures of this system of extreme 'meritocracy' at scale can be gruesome, even for much younger children, including his own daughters, who give him a first-hand view of raising a child in China. In Peter Hessler's hands, China's education system is the perfect vehicle for examining what's happened to the country, where it's going, and what we can learn from it. At a time when relations between the UK and China fracture, Other Rivers is a tremendous, indeed an essential gift, a work of enormous human empathy that rejects cheap stereotypes and shows us China from the inside out and the bottom up, using as a measuring stick this most universally relatable set of experiences. As both a window onto China and a distant mirror onto our own education system, Other Rivers is a classic, a book of tremendous value and compelling human interest.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 731

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Peter Hessler

The Buried

Strange Stones

Country Driving

Oracle Bones

River Town

First published in the United States in 2024 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Peter Hessler, 2024

The moral right of Peter Hessler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 287 3

Map artwork by Angela Hessler

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

for Ariel and Natasha

献给采采和柔柔

Contents

Part I

1. Rejection

2. The Old Campus

3. The New Campus

4. Chengdu Experimental

Part II

5. Earthquake

6. The City Suspended

7. Children of the Corona

8. The Sealed City

9. Involution

10. Common Sense

11. Generation Xi

Epilogue: The Uncompahgre River

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

CHAPTER ONE

Rejection

September 2019

THE VERY LAST THING THAT ANY TEACHER WANTS TO DO—AND the very first thing that I did at Sichuan University, even before I set foot on campus—is to inform students that they cannot take a class. Of course, some would say that rejection is a normal experience for young Chinese. From the start of elementary school, through a constant series of examinations, rankings, and cutoffs, children are trained to handle failure and disappointment. At a place like Sichuan University, it’s simply a matter of numbers: eighty-one million in the province, sixteen million in the city, seventy thousand at the university. Thirty spots in my classroom. The course title was Introduction to Journalism and Nonfiction, and I had chosen those words because, in addition to being simple and direct, they did not promise too much. Given China’s current political climate, I wasn’t sure what would be possible in such a class.

Some applicants considered the same issue. During the first semester that I taught, a literature major picked out one of the words in the title—nonfiction—and gave an introduction of her own:

In China, you will see a lot of things, but [often] you can’t say them. If you post something sensitive on social platforms, it will be deleted. . . . In many events, Non-Fiction description has disappeared. Although I am a student of literature, I don’t know how to express facts in words now.

Two years ago, on November 18th, 2017, a fire broke out in Beijing, killing 19 people. After the fire, the Beijing Municipal Government began a 40-day urban low-end population clean-up operation. At the same time, the “low-end population clean-up” became a forbidden word in China, and all Chinese media were not allowed to report it. I have not written an article related to this event, and it will always exist only in my memory.

As a student of Chinese literature, I have a hard time writing what I want to write because I am afraid what I write will probably be deleted.

Applicants handled this issue in different ways. I requested a writing sample in English, and most students sent papers that they had researched for other courses. Some titles suggested that the topics had been chosen because, by virtue of distance or obscurity, they were unlikely to be controversial: “Neoliberal Institutionalism in the Resolution of Yom Kippur War,” “The Motive of Life Writing for Aboriginal Women Writers in Australia.” Other students took the opposite approach, finding subjects close to home but following the government line; one applicant’s essay was titled “The Necessity of Internet Censorship.” There was also safety in ideology. A student from the College of Literature and Journalism submitted a Marxist interpretation of Madame Bovary. (“Capitalism has cleaned up the establishment of the old French society, and to some extent deconstructed various resistances that limit economic and social development.”) Another student abandoned every traditional subject—politics, business, culture, literature—and instead produced, in prose that was vaguely biblical, a five-hundred-word description of a pretty girl he had seen on campus:

She was a garden—her shoots are orchards of pomegranates, henna, saffron, calamus and cinnamon, frankincense and myrrh. She was a fountain in the garden—she was all the streams flowing from Lebanon, limpid and emerald, pacific and shimmering. . . .

My first impressions were literary: I saw the words before I met the students. Their English tended to be slightly formal, but it wasn’t stiff; there were moments of emotion and exuberance. Sometimes they made a comment that pushed against the establishment. (“I am still under eighteen years old now, living in an ivory tower isolated from the world outside. I’m expecting to change it.”) All of them were undergraduates, and for the most part they had been born around the turn of the millennium. They had been middle school students in 2012, when Xi Jinping had risen to become China’s leader. Since then, Xi had consolidated power to a degree not seen since the days of Mao Zedong, and in 2018, the constitution was changed to abolish term limits. These college students were members of the first generation to come of age in a system in which Xi could be leader for life.

The last time I had arrived in Sichuan as a teacher was in 1996, when Deng Xiaoping was still alive. While reading applications, I imagined how it would feel to return to the classroom, and I copied sentences that caught my eye:

Only when a nation knows its own history and recognizes its own culture can it gain identity.

Just as Sartre said, men are condemned to be free. We are left with too many choices to struggle with, yet little guidance.

Actually, all of us are like screws in a big machine, small but indispensable. Only when everyone works hard will our country have a brighter future.

The range of topics made it virtually impossible to compare applications, but I did my best. I had to limit the enrollment to thirty, which was already too many for an intensive writing course. After selecting the students, I sent a note to everybody else, inviting them to apply again the following semester. But one rejected girl showed up on the first day of class. She sat near the front, which may have been why I didn’t notice; I assumed that anybody trying to sneak in would position herself near the last row. At the end of the second week, when she sent a long email, I still had no idea who she was or what she looked like.

Dear teacher,

My name is Serena, an English major at Sichuan University, and I am writing in hope of your permission for me to attend, as an auditor, your Wednesday night class.

I failed to be selected. I have been in the class since the first week, and I sensed and figured my presence permissible.

I want to write. As Virginia Woolf thought, only life written is real life. I wish to be a skilled observer to present life or idealized images on paper, like resurrection or “in eternal lines to time thou growest.” . . . I started to appreciate writers’ diction not as a natural flow of expression but careful strategies and efforts, I began to put myself in the writers’ shoes, and set out to sharpen my ear as a way to hear the sound of writing—consonance or dissonance, jazz, chord, and finally symphony.

Perhaps I am being paranoid and no one will drag me out. If you can’t give me permission, I’ll still come to class in disguise until I am forced to leave.

Happy Mid-autumn Festival!

Thank you for your time.

Yours cordially,

Serena

I composed an email, explaining that I couldn’t accept auditors. But I hesitated before pressing “send.” I read Serena’s note once more, and then I erased my message. I wrote:

The college is concerned about auditing students, because the course needs to focus on those who are enrolled. But I much appreciate your enthusiasm, and I want to ask if you are willing to take the class as a full student, doing all of the coursework.

I was violating my own rules, but I sent the email anyway. It took her exactly three minutes to respond.

When I told other China specialists that I planned to return to Sichuan as a teacher, and that my wife, Leslie, and I hoped to enroll our daughters in a public school, some people responded: Why would you go back there now? Under Xi Jinping, there had been a steady tightening of the nation’s public life, and a number of activists and dissidents had been arrested. In Hong Kong, the Communist Party was reducing the former British colony’s already limited political freedoms. On the other side of the country, in the far western region of Xinjiang, the government was carrying out a policy of forced internment camps for more than a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities. And all of this was happening against the backdrop of the Trump administration’s trade war against the People’s Republic.

It was different from the last time I had moved to Sichuan. In 1996, I knew virtually nothing about China, and almost all basic terms of my job were decided by somebody else. The Peace Corps sent me and another young volunteer, Adam Meier, to Fuling, a remote city at the juncture of the Yangtze and the Wu Rivers, in a region that would someday be partially flooded by the Three Gorges Dam. At the local teachers college, officials provided us with apartments, and they told us which classes to teach. I had no input on course titles or textbooks. The notion of selecting a class from student applications would have been unthinkable. Every course I taught was mandatory, and usually there were forty or fifty kids packed in the classroom. Most of my students had been born in 1974 or 1975, during the waning years of the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong’s reign.

In 1996, only one out of every twelve young Chinese was able to enter any kind of tertiary educational institution. Most of my Fuling students had been the first from their extended families to attend college, and in many cases their parents were illiterate. They typically had grown up on farms, which was true for the vast majority of Chinese. In 1974, the year many of my senior students were born, China’s population was 83 percent rural. By the mid-1990s, that percentage was falling fast, and my students were part of this change. During the college-enrollment process, the hukou, or household registration, of any young Chinese automatically switched from rural to urban. The moment my students entered college, they were transformed, legally speaking, into city people.

But inside the classroom it was obvious that they still had a long way to go. Most students were small, with sun-darkened skin, and they dressed in cheap clothes that they had to wash by hand. I learned to associate certain students with certain outfits, because their wardrobes were so limited. I also learned to recognize a chilblain—during winter, students often had the red-purple sores on their fingers and ears, the result of poor nutrition and cold living conditions. Much of my early information about these young people was physical. In that sense, it was the opposite of what I would later experience at Sichuan University. In Fuling, my students’ bodies and faces initially told me more than their words.

It took a long time to draw them out. They tended to be shy, and often they were overwhelmed by the transition to campus life. We were similar in age—at twenty-seven, I was only a few years older than my senior students—but none of them had ever met an American before. They had studied English for seven or more years, although many of them had trouble carrying on a basic conversation, because of lack of contact with native speakers. Their written English was much stronger, and in literature class I assigned Wordsworth poems, Shakespeare plays, stories by Mark Twain. In essays, they described themselves as “peasants,” and they wrote beautifully about their families and their villages:

In China, passing an entrance examination to college isn’t easy for the children of peasants. . . . The day before I came to Fuling, my parents urged me again and again. “Now you are college student,” my father said. . . . “The generation isn’t the same with the previous generation, when everyone fished in troubled waters. We have to make a living by our abilities nowadays. The advancement of a country depend on science and technology.”

My mother was a peasant, what she cared for wasn’t the future of China, just how to support the family. She didn’t know politics, either. In her eyes, so long as all of us lived better, she thought the nation was right. . . . But I see many rotten phenomenons in the society. I find there is a distance between the reality and the ideal, which I can’t shorten because I’m too tiny. Perhaps someday I’ll grow up.

I felt like we had just gotten to know one another well when my Peace Corps service ended, in the summer of 1998. Before leaving Fuling, I collected the mailing addresses of everybody in my classes, although I doubted that we would be able to stay in touch. Postage to the United States was prohibitively expensive for Chinese in the countryside, and none of the students had cell phones or access to the internet. After graduating, most of them would accept government-assigned positions as teachers in rural middle schools.

Before we parted, students gathered keepsakes: copies of class materials, photographs with me and Adam. They prepared memory books with pictures and farewell messages. During my last week on campus, one boy named Jimmy approached me with a cassette tape and asked if I would make a recording of all the poetry we had studied.

“Especially I want you to read ‘The Raven,’ and anything by Shakespeare,” he said. “This is so I can remember your literature class.”

Jimmy had grown up in the Three Gorges, where he would now return. The government had assigned him to a middle school on the banks of a small, fast-flowing tributary of the Yangtze. In the memory book, Jimmy had pasted a photograph of him standing on campus with a serious expression, dressed in a red Chicago Bulls jersey. The Bulls jersey was one of the outfits I associated with Jimmy. This was the era of Michael Jordan, and a number of boys wore cheap knockoff versions of Bulls paraphernalia. My pre-graduation gift to Jimmy and his classmates had been to change the schedule of their final exam, in June 1998. By pushing the exam back a few hours, I made it possible for all of us to watch live while Jordan hit a jumper with 5.2 seconds left, winning his sixth and last NBA title.

Jimmy had never been a particularly diligent student, but he had some Jordanesque qualities: he was a good athlete, and naturally bright, and things always seemed to go well for him. In the memory book, he wrote a message in neat Chinese calligraphy:

Keep Climbing All the WayFarewell, Farewell, Dear Friend

When Jimmy asked me to record the poetry on the cassette, I was touched, and I promised to do it that evening.

“Also, after you finish the poems,” he said, grinning, “I want you to say all of the bad words you know in English and put them on the tape.”

When I returned to the United States, I often wondered how things would turn out for my students. For months, I received no updates; all I had were the photographs in the memory book and the characters on my address list. I imagined Jimmy in his Bulls jersey, surrounded by the cliffs of the Three Gorges, listening to the poems of Edgar Allan Poe and William Shakespeare punctuated by strings of curse words.

In 1999, I moved to Beijing as a freelance journalist. I no longer taught, but part of my life continued to operate on the Chinese academic schedule. At the beginning of every semester, in September and in February, I sent out a batch of letters that were hand-addressed to dozens of villages in Sichuan and Chongqing. Now that I was living in China again, it was easy for former students to write back. Their replies arrived in cheap brown paper envelopes postmarked with the names of places I had never heard of: Lanjiang, Yingye, Chayuan. Most students had beautiful handwriting—at the college, they had been forced to spend hours practicing with a traditional Chinese brush. Their graceful script contrasted with the harsh world they described:

The children show no interest in their studies. Poverty, foolishness are involved in the farmers in our hometown which is far from modern society. Several generations live with working by hand and using animals as labour force instead of tractors. The less they know, the poorer they become.

I often tell the students you must study or you won’t change your stupidness. . . . Most of the government cadres are incapable, most of them know little. In your America, that can’t be imagined. They only know eating, gambling, drinking, looking for official relations, whoring.

Over time, I was able to stay in touch with more than a hundred former students. Jimmy’s brown paper envelopes proved to be among the ones that arrived most regularly at my Beijing office. His postmark read Jiangkou—“mouth of the river” in Chinese. Jiangkou had always been poor and isolated, but soon Jimmy’s letters began to describe a life that he had never imagined possible:

In 1999, a charming girl came into my world, who worked in a restaurant then. In my eyes, she was so attractive that I fell in love with her, I promised I would love her forever. On March 15th, 2000, I married her eventually. Before we got married, she started to run a grand restaurant of her own. In my opinion, it is a hard work to do business, but she thinks it is a good job, which can develop her ability. At the beginning, we owed our relatives and friends much money. Now we also run a hotel, which cost us 170,000 yuan. To our joy, both restaurant and hotel are going very well. . . . On Sep. 5th, 2001, a baby called Chen Xi (means the rising sun) came into my family, who brought in much pleasure to us.

It was remarkable how quickly the letters changed. By the early 2000s, there were fewer descriptions of poverty, and writers referred to new highways and railroads that were being constructed in their hometowns. Details about money became common: loans, investments, side businesses. Occasionally, a former student sent a message from the factory towns of southeastern China, where so many rural people had migrated:

I am now going to Fujian. One of my cousins is working in Fujian’s Fuding city. He was injured in a toy factory there, so he is having a guansi [lawsuit]. And these days we are talking with the boss about the money he should pay for my cousin. I find this place interesting and much richer than Chongqing. And it’s easier to find a job with good salary.

Almost none of them had been born with any advantages in terms of family, finances, or geography. But their luck was historical—they couldn’t have had better timing. In 1978, when they were a few years old, Deng Xiaoping had initiated his Reform and Opening policy. My Fuling students had grown up alongside these economic and social changes, and they were part of what I came to think of as the Reform generation. Members of this cohort had participated in the largest internal migration in human history, with more than a quarter of a billion rural Chinese moving to the cities. In 2011, China’s population officially became majority urban. Since the beginning of the Reform era, an even greater number of citizens—nearly eight hundred million—had been lifted out of poverty.

From a distance, it was hard to grasp what these statistics meant at the human level. But the letters gave me a different perspective. In 2016, a man named David wrote and apologized because back in the 1990s, he had not been a particularly attentive student. It was true—in literature class, David had often slumped over his desk, half asleep. Two decades later, he finally explained the reasons for his malaise:

For three years, I did not eat and sleep well. I remember in 1996, for half a year, I just had one meal a day. I was a sad man. But now I am happy about my life.

_______

Eventually, the brown envelopes gave way to emails and text messages. My own life moved on: for a while, Leslie and I lived in southwestern Colorado, where our twin daughters, Ariel and Natasha, were born in 2010. The following year, we moved to Egypt, where Leslie and I worked for half a decade as foreign correspondents. No matter where I was, I kept the old schedule of sending out a long message at the start of every Chinese semester. I always had a notion that someday, after twenty years or so, I would return to live at the familiar juncture of the Yangtze and the Wu. I liked the idea of teaching again at the Fuling college, and I was curious about the next generation of students.

In 2017, I inquired about a teaching job. Some of my old colleagues still served on the faculty, and they reported that the college wanted to hire me. I submitted an application, which was sent to be approved by educational authorities in Chongqing, the municipality that administers Fuling. And then—nothing.

There are many kinds of rejection in China. The simplest is financial: in the business world, a denial tends to be direct and blunt. Academics can also be straightforward, especially in the exam-driven culture of Chinese schools. But if the reason for rejection is political, and if a foreigner is involved, there may be no response at all. Nobody mentions a decision, and nobody gives an explanation. The absence of communication effectively means that there is neither a problem nor a solution. It’s as if the original application never happened.

After months of silence, I knew that the only chance of clarity was through a personal visit. I made the long journey from Colorado to Fuling, where I met with a well-connected friend. I asked if there was a problem with my writing—in 2001, I had published River Town, a book about my two years at the college. But he assured me that this wasn’t the reason.

“It’s because of Xi Jinping and Bo Xilai,” he said. Bo Xilai had been the highest Communist Party official in Chongqing until 2012, when he was involved in an explosive scandal that included, among other crimes, the murder of a British businessman at the command of Bo’s wife. Before Bo’s fall, he had been seen as a figure with national aspirations and as a potential rival to Xi Jinping. In 2013, shortly after Xi rose to power, Bo was sentenced to life in prison.

My Fuling friend explained that ever since the scandal, Chongqing officials had been under close watch by the national leadership. They were unlikely to approve anything that could be seen as a potential liability, including the appointment of a foreign writer to a teaching job.

“As long as Xi Jinping is in power,” my friend said, “you will never teach in Fuling.”

His tone was slightly dramatic, as if this were a command that had been issued by the Politburo itself. For a moment we sat in silence. Then I said, “So how is Xi Jinping’s health?”

“Hen hao!” he laughed. “Very good!”

During the 1990s, in an undeveloped place like Fuling, people had a distinctive way of discussing the country’s most powerful leaders. A former student named Emily, who had spent part of her childhood in a village not far from the city, once described the experience of listening to casual conversations:

They talked about big people and big events in a way that fascinated me. The big people and big events seemed both remote and near. They were remote because they had nothing to do with the villagers’ lives; they were near because the villagers seemed to know every detail.

This combination of distance and intimacy was especially true of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Fuling residents spoke about these two figures all the time, and they quoted their sayings as casually as if remembering a conversation from last week. To a foreigner, it felt like living in a new land and learning about the gods that were worshipped there.

But Xi Jinping seemed to represent a new type of god. Early in his tenure, he initiated a strict crackdown on corruption, which appealed to many citizens, including my former students. Over time, as we settled into the rhythm of the semester letters, I started sending periodic surveys, in order to get a better understanding of their lives and their opinions. In 2017, I asked former students to name a political figure whom they admired, and Xi was by far the most popular choice:

Of course, Xi Jinping is the one I admire. I admire because he has let us benefit a lot, especially the farmers.

Honestly speaking, Xi is the first political figure in China that I admire. Under his leadership, the officials in the government are having much better service.

He is the best president in the history. He is strict with the leaders, and the leaders are behaving better now.

While praising Xi, they never mentioned personal characteristics. The old intimacy was gone; now they emphasized the ways in which the system functioned. This was part of what distinguished Xi from Mao and Deng, whose personalities and physical appearances had been central to their appeal. Mao—handsome and aloof, with a poet’s sensibility—had made Chinese people feel proud and capable of standing up to the outside world. And Deng, with his diminutive stature and Sichuanese toughness, had tapped into another part of the Chinese mindset, one that valued humility, pragmatism, and hard work. Both men had risen during the revolution, but now, after nearly seventy years of Communist Party rule, the country had reached another stage. The most powerful figure who emerged in this era was essentially bureaucratic—a god of the system.

When I met with my well-connected friend, he reminded me about this aspect of life in China. “You should try Sichuan,” he said. “They aren’t as nervous as officials in Chongqing.”

Originally, Chongqing had been part of Sichuan, but in 1997, the city and its surrounding region, including Fuling, had been designated as a separate political entity. And that was my friend’s suggestion: if you’re having trouble with Chongqing cadres, just cross the border. After our conversation, I abandoned my dream of living at the juncture of the Yangtze and the Wu. I went west: I applied to teach at an American-affiliated institute at Sichuan University. This time, the application was quickly approved, and in August 2019, I moved with my family to Chengdu.

We rented an apartment downtown, in a building that was situated on the eastern bank of the Fu River. Alongside the Fu, pleasant bike paths were shaded by century-old paper mulberry and white fig trees. The Fu was one branch of a network of small rivers and canals that, in modern times, had been given a lovely name: Jin Jiang, the Brocade River. The various streams of the Jin braided throughout downtown Chengdu, eventually continuing south to join the great rivers of lower Sichuan: first the Min, then the Yangtze. When I looked down from my Chengdu balcony onto the river, it made me happy to think that eventually, after nearly four hundred miles, that same water would flow past the city of Fuling.

Those were among my first lessons from the Xi Jinping era. Along with the new god, a new fear had permeated the government, and cadres were even more cautious than they had been in the past. But Xi remained a god of the system, which meant that the bureaucracy often operated with its own logic and momentum. If a request was rejected, it was worth trying a different office, a different cadre; in a country of such size, there were always other rivers.

At Sichuan University, I taught nonfiction in a section of campus that was still under construction. Our classroom window overlooked a stretch of mud and rubble that had yet to be landscaped, and there was often a pounding sound from workers who were installing cobblestones in a nearby courtyard. Next door, a brand-new building featured a four-story glass facade that was decorated with golden characters that read “College of Marxism.” The college had been designed with a large parking garage in the basement. Once, before an evening class, I wandered through the garage to see what the Marxists were driving to campus. Most of the cars were mid-level foreign brands, although I also saw one BMW and five Mercedes sedans.

The campus itself was enormous. From north to south, it spanned more than a mile, and the grounds were full of yellow and green rideshare bikes, to help the students cope with the distance. In the 1990s, this had all been farmland; back then, Sichuan University occupied a relatively small site on the banks of the Jin River. But the university had expanded into this rural area, which they called the Jiang’an Campus. From my downtown home, it took more than an hour by bus to get to Jiang’an. Suburban campuses had become common in Chinese cities, and Fuling had also constructed a brand-new complex, about ten miles upstream along the Yangtze.

In nonfiction class, there wasn’t a single student from the countryside. During the early weeks, I found it hard to identify physical markers among the people in my classroom. It wasn’t like the old days, when I could pick out Jimmy by his Bulls jersey, or a boy named Roger by his trademark tattered blue suit jacket, the tailor’s label still on the sleeve. At Sichuan University, there was a certain uniformity to students’ appearances. They dressed neatly, but not too well; nobody looked obviously poor and nobody looked obviously rich. The girls generally wore baggy jeans or loose skirts, and they almost never dressed in anything that was revealing or form-fitting. Few of them dyed their hair or used much makeup.

The boys’ shoes represented one of the few outward signs of prosperity. I never saw girls with flashy jewelry, but some boys wore the kind of high-top sneakers that are prized by aficionados. In every class that I taught, there was at least one student who collected throwback Nike Air Jordans. Often they wore styles that dated to the era of Jimmy and the Bulls knockoffs. But now the gear in a Chinese classroom was authentic: when I asked one first-year about his retro 1985 Air Jordans, he told me proudly that he had bought the shoes for the equivalent of $450. In nonfiction class, a sneaker-head student used “AJ” as his English name, in homage to Air Jordans.

There were a few other foreign celebrity names in that class. Some were oxymorons: a gentle kid in glasses who called himself Giroud, after Olivier Giroud, the great French footballer; and an owlish boy named Kawhi, after Kawhi Leonard, the preternaturally gifted guard for the San Antonio Spurs. A girl who called herself Giselle, after the Brazilian supermodel, was in fact very tall, very thin, and very pretty. But even Giselle dressed in an understated way. I came to think of the name as an alternative life—perhaps she would have been the glamorous Giselle in a different place, at a different time.

On the surface, the narrow range of appearance suggested a middle-class sameness. But in truth these students had arrived in my classroom from all directions. For our first unit, I assigned personal essays, and many students wrote about mothers and fathers who had migrated from the countryside. Their parents were roughly the same age as the people I had taught in the 1990s; in fact, one of my former Fuling students had a son who was currently a sophomore at Sichuan University. Those Reform-generation parents had worked hard to assimilate to city life, so it wasn’t surprising that their children dressed in unobtrusive ways. It reminded me of the United States in the 1950s, when young people had grown up amid a new prosperity. Perhaps the next generation would be more interested in exploring distinctive styles and appearances.

None of my nonfiction students had attended rural high schools, but some had spent parts of their early childhoods in the countryside. These children had often shifted back and forth between rural grandparents and parents who were trying to find their footing in new urban jobs. In some cases, the parents had been separated, not because of discord but because of the demands of a society in flux. Giselle wrote about how, at the age of six, she was sent to live with her army officer father on a military base, because her mother’s job required her to be in a different place. Giselle described the day that she arrived at her father’s apartment:

I had no idea about the man who stood in front of me. The only thing I knew about his identity was that he is my father. If you wanted me to talk more about him, I knew his bed was small and hard and his temper was not good.

In Fuling, I had also taught the children of men and women who had been caught up in immense national changes. Those events had been political in nature, with overwhelmingly tragic outcomes: the Great Leap Forward, in which as many as fifty-five million starved to death, from 1958 to 1962; and the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and lasted until Mao’s death in 1976. My Fuling students rarely wrote much about their parents’ younger lives, because the older people didn’t like to talk about it. And most of that history was either censored or glossed over in official texts. There was a blankness to the recent past—the Fuling students could only look ahead.

But family memories seemed different nowadays. The experiences of the Reform generation had been shaped by economics rather than politics, and there was a high degree of agency. People liked to tell stories, and they lingered on details. In one of the composition classes that I taught at Sichuan University, a student named Steve wrote about the experience of eating hot pot with his father. In the story, the older man took a long time in choosing a restaurant, and then, after the food arrived, he insisted on a specific order to the way it was cooked: fatty meat before lean, lean meat before vegetables. This was important, the father explained to Steve, in order to properly flavor the broth. When a waiter arrived with a plate of thin-sliced raw mutton, the father turned it upside down. He told Steve that fresh mutton should stick to the plate.

In the essay, Steve described these meticulous rituals, and he concluded:

My father was born in 1972, when the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was going to end soon. The economy of China began to rise again, but was not still good enough. Therefore, he was never starving in his childhood or adolescence, but he seldom felt full in that period of time. He told me that his family could barely eat meat once a week, and there were only a few dishes. In 1990, he started his college life and got his first part-time job. When he got his first salary, he decided to spend half of it to have an excellent meal, which brought him great pleasure.

A student named Fenton compared his parents’ stories to superhero films. He used the word fight, but not in the Maoist sense of a conflict between social classes or groups. For Fenton’s parents, the fight had been to become city people:

My parents were born in rural Shandong in the mid-1970s. Although [they] only have high school education, they didn’t want to stay in their hometown and become the next generation of farmers, so they come to the city to fight.

Before I left home and went to college, I had such an interest in listening to my parents’ stories about their childhood. Before they graduated from high school and left the countryside, as they said, it was the hardest and happiest time. When my dad was at my age, he worked as a taxi driver and my mother was a woman worker in a state-owned flour factory. I was born in the crossroad of two centuries. Taking advantage of the rapid development of market economy in the coming century, they decided to devote themselves to industry. It can be said that they are [two] of those people who have received the dividend of Reform and Opening.

But these are the stories [from] when they grew up and what I like is that they are the stories of their childhood in the countryside. These stories have a fairly fixed and smooth pattern, which can be said to be similar to the current [superhero] genre films. “Our childhood living conditions were not good” is always the beginning of this kind of story. In the middle is something that seems to be easy to realize now but was difficult to achieve at that time. And “you must cherish everything you have now” is always the end of these stories.

_______

Fenton was a friendly kid with round glasses and a crew cut, and he majored in journalism. Like many of my students, he hoped to continue his education abroad, and he had chosen the name Fenton because it sounded vaguely like his Chinese name, Huidong. After entering the private economy, Fenton’s parents had started a small factory that manufactured plastic bags. The bag money allowed them to supplement Fenton’s education with outside tutors, and he had tested into his city’s best public high school. The bags also must have fed the boy well: Fenton stood over six feet tall, with a stocky frame.

Most of the boys in the class were taller than me, and so were a few girls, including Giselle. During our first session, I showed a class photograph from the early months of 1997, when my senior students and I had stood in front of the Fuling college library. The library had been one of the most distinctive structures on campus, with bright yellow paint, and it was often used as a backdrop for photos. In the 1997 picture, I towered over my students, almost as if they were middle school kids. The image made the Sichuan University students burst out laughing—I was only five feet, nine inches tall.

Of all the characteristics of today’s young people, their height struck me at the most visceral level. I felt it in the city, too. In the old days, on crowded buses, I had been half a head taller than most people around me; now in a packed Chengdu subway I often found myself looking into some kid’s armpit. In 2020, a study in The Lancet reported that out of two hundred countries, China had seen the largest increase in boys’ height, and the third largest in girls’, since 1985. The average Chinese nineteenyear-old male was now more than three and a half inches taller, because of improved nutrition.

They were also far more likely to go to college. My students frequently referred to “985 universities” and “211 universities,” classifications that hadn’t been used when I taught in Fuling. The numbers 985 refer to a date: the fifth month of 1998, when Jiang Zemin, the leader at the time, had delivered a speech about Chinese education at Peking University. That was near the end of my Fuling years, although I didn’t remember any colleagues or students taking notice of Jiang’s speech. He was not among the Chinese leaders who were spoken of as gods, but he was shrewd about his limits. A Western-style politician would have begun such a speech by describing his own educational experiences, which, in Jiang’s case, were impressive. In 1947, he had graduated with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, a rare achievement at that time. As a young man, Jiang worked in automotive engineering in northeastern China.

But Jiang undoubtedly knew that it was risky to elevate details from his own life. And so his speech followed another Chinese narrative genre: the non-personal non-story of a Party man who knows that the system matters much more than any individual. Rather than talk about himself, Jiang connected his message to a god from the past:

Comrade Deng Xiaoping has repeatedly taught us that science and technology are the primary productive forces. We must respect knowledge and talent. These important thoughts are the theoretical basis of our strategy of rejuvenating the country through science and education. . . . In order to realize modernization, our country should have a number of world-class universities.

This campaign eventually became known as Project 985. Logically, it should have been named after Jiang—he was the first general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party with a proper university degree, and no other leader did more to advance the cause of higher education. But personifying the campaign would have made it vulnerable to politics, which was probably one reason why it was named with a string of numbers. Sichuan University was one of thirty-nine upper-tier institutions that eventually benefited from Project 985, which provided increased funding from the central government. Another campaign was called Project 211, whose numerology was even more obscure: during the twenty-first century, one hundred Chinese institutions would be granted extra support. Along with these national-level programs, there were countless other efforts to improve and expand institutions. When I taught in Fuling, the college had been relatively low on the spectrum of Chinese higher education. But even such a school was highly selective, because there were so few students who tested into any kind of tertiary institution. Since then, the nation’s low figure for college entrance—one out of every twelve young Chinese, or 8.3 percent, in 1996—had risen, in the span of little more than two decades, to 51.6 percent. Most people now made it into college, which was why China had constructed so many new campuses.

In nonfiction class, we occasionally looked back at the earlier era. During the unit on personal essays, I assigned a few pages from the beginning of River Town. In the excerpt, I described my arrival in Fuling, in September 1996. That month, the college had hosted a series of events and activities to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the Long March, the five-thousand-mile trek that Mao and the rest of the Red Army had made across China as part of their struggle to win the civil war.

The Long March had ended in 1935, but Fuling celebrated the sixtieth anniversary a year late. Some students and professors had engaged in a commemorative trek, which took longer than expected; in a remote place, everything seemed to lag a step or two behind the major cities. But the delay had no effect on the enthusiasm of the various Long March commemorations. At every event, Communist Party leaders addressed the crowd with rousing speeches, exhorting the students to love the revolution and the Motherland. One evening, there was a Long March Singing Contest, which Adam and I attended. I described the contest in my book:

For the Long March Singing Contest, all of the departments practiced their songs for weeks and then performed in the auditorium. Many of the songs were the same, because the musical potential of the Long March is limited, which made the judging difficult. It was also confusing because costumes were in short supply and so they were shared, like the songs. The history department would perform, resplendent in clean white shirts and red ties, and then they would go offstage and quickly give their shirts and ties to the politics department, who would get dressed, rush onstage, and sing the same song that had just been sung. By the end of the evening the shirts were stained with sweat and everybody in the audience knew all the songs. The music department won, as they always did, and English was near the back. The English department never won any of the college’s contests. There aren’t any English songs about the Long March.

At Sichuan University, we read this excerpt in the middle of September. I showed some old photographs from the Long March Singing Contest, and I asked the class if there was anything that struck them. Somebody from the College of Literature and Journalism raised his hand.

“We just did this last week,” he said. He explained that Sichuan University had held a singing competition in honor of the upcoming National Day. October 1 would mark seventy years since the founding of the People’s Republic, and this year’s celebration was planned to be especially elaborate. It would be the first major political anniversary under Xi Jinping.

“It was the same as in your book,” he continued. “They also sang only a few songs, because there aren’t many songs about it.” Some students laughed, and he said, “But actually it’s not correct that this makes the judging difficult. If all the songs are the same, then it’s easier to tell who is doing a better job. It’s easier to compare.”

I had never considered that possibility, but it made sense. I told him that maybe I should go back and edit that part of the book. After class, somebody sent a link to a story on the university’s website:

PRAISE THE NEW CHINA AND SING THE NEW ERA

Celebrating the 70th Anniversary of theFounding of the People’s Republic of China,

Sichuan University Holds a Faculty and Staff Choral Competition

A series of photographs looked exactly like the old days in Fuling: long rows of singers, all dressed identically, standing against a backdrop of red Communist flags. There was a picture of a stern-faced Party official standing before a podium. The report quoted her speech:

I hope that in the next choral competition, everyone will integrate their love for the Motherland into their beautiful singing, sing praises for the glorious history of the great Motherland, cherish the historical footprints of the revolutionary martyrs, reflect the character of Sichuan University faculty and staff, and gather together to realize the majestic national rejuvenation.

According to the story, more than twenty-six hundred faculty members had participated. The winners were listed, along with song titles: “My Motherland and Me,” “I Love You, China,” and “The Motherland Will Not Forget.”

In my new life as a teacher, the city was bigger, the campus was bigger—even the students were bigger. Young Chinese were now more than six times as likely to attend college than the students of their parents’ generation. Universities had been expanded or rebuilt on a scale that was almost unimaginable, and the per capita GDP was sixty-five times higher than it had been at the start of the Reform era. More than a quarter of a billion farmers had been transformed into urban citizens. But I still taught next door to the College of Marxism, and the university still hosted old-school Communist rallies. The fact that the anniversary numbers were getting higher only underscored how much had stayed the same. Same rallies, same images, same songs—“The Motherland Will Not Forget.” Of course it won’t forget, not with the same things happening over and over. Even the cadres of the same Party wore the same expressions while giving the same speeches with the same words. For a returning teacher, this was a mystery: How could a country experience so much social, economic, and educational change, while the politics remained stagnant or even regressive?

In nonfiction class, Serena was one of the students who seemed to have missed out on improved nutrition. She stood barely over five feet, and she was small-boned, with a quick smile. Like most of her classmates, she dressed in an informal, nondescript manner: jeans, T-shirts, plain skirts. She had chosen her English name after Serena van der Woodsen, the protagonist of the American teen television drama Gossip Girl. In Serena’s hometown of Nanchong, a fourth-tier city in northeastern Sichuan, she had studied English by watching Gossip Girl episodes online. Now the name embarrassed Serena, who believed that it marked her as a bumpkin, but she felt it was too late to change.

In one essay, she described herself as “low-income class.” Neither of her parents had attended university, and they worked middling jobs in Nanchong, which had a reputation for being inward-looking. Online, people mocked it as “Yuzhou-chong,” which means, roughly, “Universechong,” because citizens were so wrapped up in the petty issues of their provincial town. Serena’s admission to Sichuan University had been a stroke of great fortune for the family. Anybody who tested into a 985 university paid much less than she would at a lower-tier institution, which was one of many motivations for high school kids to study hard. It was the opposite of the American system, in which elite universities are typically more expensive. Serena’s tuition at Sichuan University cost about seven hundred dollars per year.

Admission to the college was one of many ways in which Serena had started to escape the Nanchong universe. Her attitude toward gender issues was another point of departure. Years ago, Serena’s mother had temporarily quit working in order to help support her daughter’s studies. As far as Serena was concerned, this had been a waste of the woman’s talents. She wrote in an essay:

My mother used to hand in all her money to my dad, stopped working, and became very dependent. She has realized it, regretted it, so there is not much I could say. Sometimes I feel sorry for them because they haven’t learned much, sometimes I feel sorry for us [college students] that we are in this “gilded cage.”

Chinese college students tend to be cloistered, and the Jiang’an Campus was surrounded by a high wall that ran for more than four miles—twice the length of the famous wall around the Forbidden City in Beijing. Serena was among the students who chafed at the campus restrictions, and she was outspoken in class discussions. Every week, she positioned herself at the front of the room, and she immediately established herself as perhaps the best writer in the group. Her presence as the only rejected student was a constant reminder of my own poor judgment.

One of my goals was to have students undertake reporting projects beyond the campus walls. I had never attempted such a thing in Fuling, and I wasn’t sure if it would cause problems at Sichuan University. Fenton told me that even the journalism majors rarely did much reporting. Their coursework focused primarily on theory, and on the few occasions when students researched off-campus, they invariably worked in groups under close supervision. In the current political climate, Chinese journalists were strictly limited in terms of what they were allowed to cover, and many young people were fleeing the field. On the Jiang’an Campus, it seemed symbolic that the journalism department was in the same building as the College of Marxism.

By week four of the semester, the grounds outside my window had been landscaped with freshly laid sod and a network of cement paths. One day, workers arrived with dozens of trees in flatbed trucks, and by the afternoon the paths were shaded. Working in such an environment made me impatient, and I decided that the students were ready to start reporting. I introduced some techniques for interviewing, and students practiced by talking to workers on campus. When I asked them to submit research proposals, they were more adventurous than I had expected:

[I want to research] a gay bathroom near the Dongmen Daqiao. I know it sounds like a crazy and bold idea, but I also think it has some value. It reflects the living of this sexual minority group and problems that cannot be ignored.

Chengdu Jiuyuan Bridge and bar street. There are many stories happen there, for love, freedom, and sex. I want to talk about the Chengdu bar culture. I like drinking, so I have some experience there, and I heard some stories.

I was in hospital for a long time in my childhood. I changed from hospital to hospital. I met doctors who were irresponsible and left lifelong pain on their patients, and also those devoted and friendly. Hospital is a great place [for research], where you can see how people deal with death, the relationship between patients and doctors, and even, we can see a very small part of China’s medical care system.

In Serena’s proposal, she wrote:

I want to write about a previous Protestant and now Catholic woman who volunteered to work in church. Depending on the information I can gather, my topic will probably be how religion works in China, like how non-religious people view religious groups, especially inside a family.

_______

At the end of every day, my family ate dinner on our balcony. We lived on the nineteenth floor of a forty-three-story building, and our view looked south and east to the Jin River. In late afternoon, the autumn temperature was pleasant, and a soft light reflected silver on the water. It was rare to see more than a few miles into the distance. Chengdu is situated at the western edge of a deep basin, bordered by the high massif of the Himalayas, whose peaks often shed a heavy fog onto the city. On a typical evening, when we ate dinner, the far end of the Jin vanished into the mist, and the great cities of China felt a world away: eight hundred miles to Hong Kong, twelve hundred to Shanghai. We were closer to Hanoi than to Beijing.

Like many parts of Sichuan, Chengdu has a reputation for being self-contained—a city of the basin. There has always been a strong community of artists, poets, and novelists, and during our first month, a group of writers and other literary people invited Leslie and me to dinner. We met in a restaurant that was perched high on a covered bridge above the Jin. At dinner, the hosts complained about the political climate.

“This is the worst it’s been for many years,” said one man who was involved in publishing.

“You’re lucky that your books were already published,” another writer said to me. “They couldn’t be published now.”

My first book to be translated on the mainland had appeared in 2011, the year before Xi Jinping came to power. Leslie’s book, Factory Girls, had been published in Chinese two years later, when the climate had already started to tighten. Once a book was published, it was rarely yanked from the shelves, but nowadays editors had become more cautious about putting out new material. Earlier in 2019, I had published a book in the U.S. about Egypt, but my Shanghai publisher decided that it was impossible to put out a Chinese translation.

At dinner, I explained that the censors were wary of anything about the Arab Spring. “They don’t want the word zhengbian in a book, even if it’s about another country,” I said. In Chinese, the term means “coup d’état.”

“I’m not surprised,” one writer said. “Especially with the protests in Hong Kong.”

The writers were still working on new projects, but they planned to wait for a better moment to publish. It was a common experience for Chinese intellectuals, who were forced to negotiate the ebbs and flows of Party control.

One writer teased Leslie and me about our timing. He noted that we had moved to Cairo in 2011, during the first year of the Arab Spring; we had witnessed the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood, the subsequent military coup, and the massacres that were carried out by the Egyptian security forces. In 2016, we had returned to America shortly before Donald Trump was elected.

“Everywhere you go, something bad happens,” the writer said. “And now you’ve come to China. So something bad is probably going to happen here, too!” All of us laughed, and somebody raised a toast; the conversation moved on. There was wood all over the restaurant and I should have knocked it, but that wasn’t something people did in Sichuan.

CHAPTER TWO

The Old Campus

October 2019

IN THE 1990S, FULING TEACHERS COLLEGE OCCUPIED A LUSH, GARDEN-like campus, which was situated on the steep eastern bank of the Wu River, about a mile from where the tributary emptied into the Yangtze. Back then, the college was a three-year institution that awarded only associate’s degrees. It was home to around two thousand students, a figure that, in the years since, had increased to more than twenty thousand. Such growth was common among Chinese institutions of higher education. Many universities in Sichuan and Chongqing had increased their enrollments tenfold, and a number of teachers colleges, including the one in Fuling, had been upgraded to four-year institutions that awarded bachelor’s degrees. In 2005, as part of this transition, the Fuling college was relocated to a stretch of previously undeveloped farmland on the Yangtze’s northern bank. This move followed the lines of the local rivers—one mile downstream on the Wu, five miles upstream on the Yangtze—as if the entire institution had been picked up and hauled away atop some massive ship. Once the college had been reassembled on the brand-new campus, it was also given a brand-new name: Yangtze Normal University.

Afterward, a small section of the old campus was sold to developers. They tore down the gymnasium, the auditorium, and a few other buildings, replacing them with high-rise apartment blocks. A middle school opened at one end of the site. But there was a long delay in demolishing the majority of the old campus. Locals told me that private developers had expressed interest, but college administrators set a high price. After developers refused to meet the offer, the administrators responded with one of the classic moves in Reform-era bargaining.