Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Sima Samar has been fighting for justice all her life. Born into a polygamous family, Samar agreed to an arranged marriage to continue her own education. Once she had qualified as a doctor, she took off into rural areas – on horse, donkey, even on foot – to treat people who had never received medical help before. As the situation worsened, Samar found herself working in increasingly adverse circumstances, and in grave personal danger. After Samar's husband was disappeared by the regime, she faced a choice: to accept the injustices she saw around her or to keep driving for a better Afghanistan. From selling her own hand embroidered bed quilt to pay for her degree, to becoming Vice President in an office with no heating and only beach chairs, Samar has worked tirelessly for human rights in Afghanistan – the worst country in the world to be a woman. In Outspoken, Samar writes unapologetically and unflinchingly about the colossal internal and international political failures that have engulfed Afghanistan over the past five decades – the corruption, tribal tensions and hijacking of religion. But it is also a powerful story of loyalty, diplomacy and integrity; a vision for a brighter dawn.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

OUTSPOKEN

“Afghanistan, often referred to as ‘the graveyard of empires,’ has been described and explained at length by foreigners, usually men. This book provides an illuminating view of contemporary— I hesitate to say modern—Afghanistan, from a woman who weaves the personal and the political into the story of her successes and dreams, but who never gives in to despair. Sima Samar’s life and work stand in defiance to the dark rule of the Taliban, as a promise for a better future for all Afghans, even when the whole world seems to have abandoned them.” Louise Arbour, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

“Outspoken is a book of miracles, large and small. It’s a history book, an adventure story, a deeply personal memoir and an inspiring work that propels you from your couch into action. Dr. Sima Samar gives bravery a face, from the night she saw her first husband taken away to be killed, to the many nights she risked her own life to save others. Illuminating the darkness in Afghanistan’s recent history, Outspoken provides astonishing insights and analysis. Honestly, I couldn’t put it down.” Lisa LaFlamme, Journalists for Human Rights

“Outspoken invites the reader into the heart of a country, to witness its people’s resilience and their strength. Despite the many treacherous paths Afghans have traveled over more than forty years of war, Sima Samar shows us the beauty of the Afghan soul and the wonder of Afghanistan. The very definition of courage, Sima Samar has fought tirelessly, through personal pain and tragedy, facing down successive repressive regimes—and even a few allied to the West—in her quest for justice. She is a hero indeed.” Kathy Gannon, author of I Is for Infidel, former Associated Press news director

“For two decades, Sima Samar was the conscience of democratic Afghanistan—a physician, human rights advocate, institution-builder, and justice-seeker. She embodied the ideals of her country’s revival after 2001 but paid a heavy price. Her story is essential and inspiring reading for all Americans, complicit as we are in a tragedy from which we must not turn away.” Steve Coll, author of Ghost Wars

“In Outspoken, Sima Samar relates her lifelong struggles against patriarchy: as an Afghan girl, a medical doctor, a refugee in Pakistan who built hospitals and schools, a government official, and a human rights defender. Her story trenchantly illuminates what we must all learn from interventions in Afghanistan and serves as a warning to the world at a time when women’s rights are under siege.” Emma Bonino, former EU commissioner and former foreign minister of Italy

“Outspoken is a must read for every woman—indeed for every person— who supports equality and human rights, especially for women and girls. Dr. Samar’s life is an inspiration; she speaks truth to power and has repeatedly risked her life for doing so. Feminists worldwide can and must learn from her experiences.” Eleanor Smeal, president, Feminist Majority Foundation and publisher, Ms. Magazine

“Afghanistan’s unsurpassably sad last half century ranks among the most dismal and disastrous episodes in all of human history. Sima Samar lived at the epicenter of this evil storm and has spent her life working tirelessly to improve the lives of her fellow Afghans, always holding on tenaciously to the hope for a better future. Outspoken is a book that is sobering, necessary—and absolutely riveting.” Paul Kennedy, former host of CBCIdeas

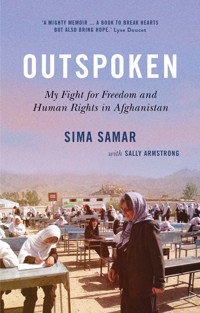

OUTSPOKEN

My Fight for Freedom and Human Rights in Afghanistan

SIMA SAMAR

withSALLY ARMSTRONG

SAQI BOOKS

Gable House, 18–24 Turnham Green Terrace

London W4 1QP

www.saqibooks.com

Published in Great Britain 2024 by Saqi Books

Copyright © Sima Samar 2024

Sima Samar has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Text design: Matthew Flute

Jacket design: Matthew Flute

Image credits: courtesy of the author; (sky) Guillaume Galtier / Unsplash

All rights reserved.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-0-86356-898-5

eISBN 978-0-86356-884-8

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

To the people who lost their lives and whose graves remain unmarked as a result of forty-five years of war in Afghanistan.

To the women of my country who live under a regime of gender apartheid.

To all those who suffer from patriarchy and gender-based violence worldwide.

CONTENTS

Map

Prologue by Sally Armstrong

OneEYEWITNESS

TwoGIRL CHILD

ThreeSTORM WARNINGS

FourTHE DOCTOR IS IN

FiveA FUNDAMENTAL THREAT

SixACCUSED

SevenNO PEACE WITHOUT JUSTICE

EightTHEY THOUGHT THEY COULD BURY US

NineTRUMP AND THE TALIBAN

TenTHE IDES OF AUGUST

ElevenGETTING TO NEXT

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Index

AFGHANISTAN

PROLOGUE

by Sally Armstrong

IT BEGAN AS A QUEST and turned into an odyssey. The Taliban had taken over Afghanistan in late September 1996 and forbidden education for girls and working outside the home for women— basically putting women and girls under house arrest. During that time, I was the editor in chief of the Canadian magazine Homemaker’s, and we covered many important issues of the day. I heard about a woman who was defying the Taliban edicts, keeping her schools for girls open and her medical clinics for women running. I wanted to interview her for a story I was writing about this incomprehensible return to the Dark Ages. But first I had to find her.

My quest included dozens of phone calls and scouring the news for the name of this woman. At last, I talked to human rights expert Farida Shaheed in Lahore, Pakistan, who said, “Come over here and we’ll discuss this.” Despite an editorial budget seriously strained by the cost of a flight, I left immediately.

I met Shaheed at her office, where women were being educated about the duplicity of their religious-political leaders. Shaheed was a fountain of information, teaching me the ABCs of militant fundamentalism. But then she told me, “I can’t give you the name of the woman you seek—she’s in danger of being killed.” At about 5 p.m., when I was despairing my decision to fly across the world, Shaheed said, “There’s a flight to Quetta tomorrow at 9 a.m. You should be on it. Someone will meet you in the arrivals lounge.”

It was an easy flight to this city about 700 kilometers west of Lahore. By the time the plane landed my curiosity was thoroughly piqued. When I walked into the arrivals lounge a woman approached me, smiling. She extended her hand and said, “You must be Sally. I’m Sima Samar. I believe you’ve been looking for me.”

And that’s when the odyssey began. For the next week, I followed Sima around the hospitals and schools she was operating for women and girls. I discovered that she is the quintessential Afghan woman: she’s strong, she adores her country, and she’s had to fight for everything she’s ever had. Sima Samar was only twelve years old when she learned the meaning of the words author Rohinton Mistry would later write that life was poised as “a fine balance between hope and despair.” At that tender age she began to fight to alter the status of women and girls in her country. She fought the traditional rules for girls in her own family. She fought the Soviets, the mujahideen, the Taliban. She fought every step of the way to get an education and become a physician, to open her hospitals and schools for girls, and to raise her children according to her own values.

The article I wrote resulted in more than twelve thousand letters to the editor from women demanding action for the women and girls of Afghanistan. Some of the letter-writers started Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan, and similar associations sprang up around the world. They all asked Sima to come and speak. After 9/11 and the subsequent defeat of the Taliban, US president George W. Bush invited her to the State of the Union address in 2002 and introduced her as the face of the future of Afghanistan. At every podium in Europe, in Asia, in North America, she told her heart-wrenching story and was received with standing ovations, cheers and promises. She was a journalist’s dream, sharing her stories with authenticity, passion and even humor. Little did I know that when my journalistic quest was finished the odyssey would continue for more than two decades.

As our friendship grew, I became her witness—when the Taliban threatened to kill her; when the government that formed after the Taliban was defeated in 2001 tried to sideline her; when she defied the naysayers and became the first-ever Minister of Women’s Affairs; and when she started the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC). I traveled to the central highlands with her to see her far-flung schools in action, and I was with her family when suicide bombers struck at the meeting she was attending at the Serena Hotel in Kabul.

When Sima visited Canada, she met my family and even swaddled my first grandchild. And when I visited her country, I sat on the floor cross-legged around the dastarkhan at dinner with her family and learned more about Afghanistan and Afghans than I ever could have imagined.

I watched her fight back, bristled at the threats she received and grinned at her audacity. When it comes to justice and equality, she simply does not take no for an answer. I remember one occasion when the Taliban demanded she close her schools for girls and said if she did not, they would kill her. She replied, “Go ahead and hang me in the public square and tell the people my crime: giving paper and pencils to girls.”

I urged her to tell her own story when the Taliban, following on disgraceful backroom deals made with the United States, returned to power. While the world saw the twenty-year international intervention in Afghanistan as a failure, the truth is that during those twenty years, life expectancy in Afghanistan went from forty-seven years to sixty-three years, the boys and the girls went back to school, and nation-building began. That isn’t a failure—it’s a miracle. Sima was one of the leaders behind those remarkable changes, and I told her that the future of her country might depend on the honest telling of the chronicle of women, tradition, human rights and justice. What’s more, she was in a position to know exactly why the government eventually collapsed. I saw her life of resistance and resilience as a cautionary tale to others who allow deception and misinformation about culture and religion and gender to overrule the history and ultimately the will of the people. This is her story.

One

EYEWITNESS

“I have three strikes against me. I’m a woman,I speak for women and I’m Hazara—the mostpersecuted ethnic group in Afghanistan.”

IT BEGAN AS A SPARKLING MAY MORNING on an otherwise ordinary day. The weather was perfect, sunny and warm with a light breeze blowing springtime into Kabul. The blossoms had drifted off the trees, making way for leaves to burst onto the branches. It was approaching the end of Ramadan, the holy ritual that requires prayers and fasting for thirty days, so the anticipation of Eid, the celebration that marks the end of fasting, was on everyone’s mind. Families and friends would gather to pray and give thanks and to savor traditional foods like steaming platters of Kabuli pulao, ashak, bolani, lamb kabobs, delicious sheer pira and, of course, each other’s company. For a country that had experienced so much bloodshed and so many setbacks, this rebirth season of spring could have been seen as a sign of deliverance. But on that day—May 8, 2021—at 4:27 p.m., when the first explosion tore into the Sayed Al-Shuhada school in Dasht-e-Barchi, a neighborhood in West Kabul where members of the Hazara ethnic minority live, my hopes for the future were dashed and my heart broke—again.

Although I could not have predicted it at the time, this was in fact the beginning of the end of the Afghanistan I had helped to rebuild. The events of May 8—the who, the why and the what—go a long way to describing the wrongs that need to be righted if my country is to see a new beginning.

The warning that day came by way of a beeping from my cell phone. I was in the midst of a meeting at Gawharshad University, where we were discussing a hopeful future, including a new research department and the enhancement of the program for women’s empowerment. A horribly familiar chill crept up my spine when I saw the message that flashed on my screen—explosion Dasht-e-Barchi. In such a crowded part of the city I knew there would be bloodshed, but I hoped that the casualties would be few and the wounds minor. Still, it was impossible to forget the terrible attacks Dasht-e-Barchi had already experienced: at the education center, the sports club, the wedding hall, the maternity hospital, and several mosques. Casualties had been high.

The discussion at the table blurred as I kept checking my phone. The second text appeared minutes later with words that struck me like shrapnel: girls, school, death. By now everyone at the table was staring at their phones. Dasht-e-Barchi is the district where the Hazaras live, where men work menial jobs as laborers so they can scrape together the funds needed to bring their families from the central highlands of Afghanistan, which is the traditional home of the Hazaras, to the city and the promise of education for their children.

When the third text hit my screen, it felt as if the story was unraveling like Afghanistan itself. The first report was that it was a rocket attack on the Sayed Al-Shuhada school. Then a car bomb exploded at the scene as bystanders ran to help the injured. A third and fourth explosion followed, and casualties mounted.

Of course, I wanted to race to the scene—I’m a medical doctor, I’m a mother. But I knew the chaotic traffic and intense security checks in Kabul would hold up the rescue and I wouldn’t be able to get there in time to help. I called a halt to the meeting and went home, where I turned on the television to try to comprehend the causes and consequences of this horrific act of violence on blameless schoolgirls.

The coverage was hard to watch. The street in front of the school was crowded with carnage—the bodies of little girls, their schoolbooks and backpacks and shoes strewn about. Limbs left at incomprehensible angles. People screaming, searching, panicking. Blood ran down the road like rainwater. Every means of transportation was being used to get the girls to medical facilities—cars, motorcycles, bicycles and rickshaws were pressed into action. The wounded were even being hoisted onto shoulders and carried away. Survivors were torn between running for their lives and staying to help classmates. Others called to onlookers to run to clinics to give blood. The injured were crying out for their mothers and begging for help while fires continued to burn all over the street. Journals of poetry and scrapbooks of artwork were consumed in flames. The notebooks held the dreams of becoming “a somebody,” as the kids here like to say: a doctor, a police officer, an engineer or a teacher who could improve the life of the family and the future of the country.

I knew that poverty would prevent the wounded from being treated with the most advanced techniques. The father of a girl who suffered multiple fractures later said he had no money to buy the pins to rebuild his daughter’s arm. As with everything else in their hardscrabble lives, they would have to put up with less. And for those who now had to deal with complicated injuries and disabilities, it meant more debt and hardship; for all of them, it would mark the beginning of an enduring trauma born from barbarity.

The school, which boys attend in the mornings and girls in the afternoons, stretches over a few city blocks backing onto a hill covered with small mudbrick houses where many of these families live. The girls, dressed in the ubiquitous black-dress-and-whitescarf uniform, had come to this place to learn. For the Hazaras who arrived here from the Waras district of Bamiyan in the central highlands, this neighborhood is stuffed with hopes. There’s a mural on the wall at Sayed Al-Shuhada school with words that read: “Your dreams are limited only by your imagination.”

They already know hardship. As is true for so many kids in this poor part of the city, their daily lives include a shift of carpet weaving to supplement the family income. The owners of the carpet companies have shrugged off the severe criticism for using child labor because they know it’s the small fingers of a child that can weave the threads rapidly and follow the intricate patterns precisely. (While I have lobbied for a stop to child labor, I do not pass judgment on poor people who are trying to educate their children in a country that has no social security.) The children earn a meager amount, maybe ten to fifteen dollars a month, while they sit on benches just centimeters from the loom. Their fingernails are broken and split; the skin beside the nails is torn from threading the tough wool fibers through the apparatus. Because they are confined to a closed room, often working in tiers stacked on top of one another, they inhale the fluff from the wool and develop chronic lung disorders. They get few breaks, often falling asleep at the loom, and are forbidden to make conversation lest it distract them from the pattern. Silence at the loom is broken only by the sound of children coughing and the rhythmic tone of the shana, the comb used to pull the knots they make into the weaving.

Still, at school, these youngsters chased their dreams, even trying their hand at activism to fulfill them. Only a week before the attack a group of them went to the media to let the government know that the school didn’t have enough books to go around. In their seriously overcrowded building, the children didn’t mind sitting on the floor and out in the halls, but books were a priority they decided to fight for.

My thoughts were swirling around the events unfolding on the television screen when I glanced out the window and noticed a bird building a nest. I was immediately struck by how carefully the bird was weaving the tiny bits of twigs and dirt and string to build this nest where she would bring new life into this world, and how she was doing so without destroying any part of the environment. I watched that little bird working feverishly to prepare the nest and considered how easily a heavy rain or a fierce wind could destroy it. I remembered a woman from Kandahar coming to me and saying, “What have I done wrong in my life? Three times I built a nest and storms came and destroyed my nests, but the storms were man-made.” So many in my country have suffered because somebody else wanted their land or their lives or to have power over them.

It had taken forty-five minutes for ambulances, fire trucks and police to get through the streets of Kabul to this west-end neighborhood at the height of afternoon traffic. The sounds of the sirens mixed with the shouting of parents and the pleas of the victims and the physical gore on the street to create a heart-stopping tableau of a people under attack—my people.

While no terrorist group took responsibility for this horrible strike, everyone here knows that trouble begins with the Taliban. If they didn’t do it, they know who did.

Most of the world sees us as a people at war. And war has a way of coloring a country various shade of gray; the guns, tanks, dust, mud and rubble blur into a single hue. To most of the world Afghanistan has been presented in the recent past as nearly colorless, a sepia image of treeless mountains and endless deserts populated by beige-blanketed, bearded men with dashes of periwinkle blue provided by burka-covered women. The overall impression is of a place that is dreary, oppressive, backward and dangerous. But there is so much more to our country—from the legacy of the Persian cultural and linguistic sphere to the acclaimed lattice Jali woodwork and the celebrated Nuristani (chip-carving) techniques. Our Istalifi pottery and ceramics and calligraphy, even our beautiful carpets on display at the famous Turquoise Mountain in Kabul, are often missed by the masses of soldiers, politicians and diplomats who come here because of continued conflict. The best of us is overshadowed by the fabled stories of the British invasion in 1839 and the Russian occupation that began in 1979 and the 9/11 attacks in America that brought the world to our door.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the United States acted on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) Article 5 on collective defense, which calls on all members to rally to the side of the one who has been attacked—in this case the United States—and prepare to make war on the aggressor, in this case the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

The invasion on October 7, 2001, named Operation Enduring Freedom, was welcomed by most Afghans. People were tired of conflict, of the violation of their rights, particularly women’s rights; they were fed up with the lack of accountability and justice. But with rare exceptions, the story became a story of their soldiers and our poverty, of their sacrifices and our ethnic strife. There is so much more to this landlocked country on the ancient Silk Road: Both the spectacular Nuristan and Panjshir Valleys, with stunning landscapes of mountain peaks and a rushing river that by turns roars and gurgles through the provinces; the spiritual meadows of Bamiyan; the gentle Shomali Plain, our fertile breadbasket that contrasts with the deserts and stand-alone rock mountains and the endless dust of Kandahar and the brilliant colors of the historic mosques of Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif. As for the people—loyalty, friendship, protection and hospitality are in the DNA of Afghans. We are so much more than our quarrels.

There are four major ethnic groups in my country. While there are no clear boundaries and there is much overlap, each one is powerful in its own right. (A proper census has not been conducted since 1979, so population numbers and the precise ethnic makeup of the country are inexact.) Pashtuns, who make up about 40 percent of the population, are the largest ethnic group and the most influential in business and politics. Originating in southern Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan, they follow Pashtunwali, a traditional and cultural code based on honor, revenge and hospitality—and that is rooted in a strict patriarchy. Pashtuns were among the ranks of the mujahideen (guerrilla fighters) during the Soviet occupation. The recent presidents Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani are Pashtun. So are the majority of the Taliban.

Tajiks, at about 25 percent of the population, form the second-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and speak Dari as opposed to the Pashto language spoken by Pashtuns. Tajiks are one of the most ancient of the surviving Central Asian people. While they live in Herat, next to the border with Iran, and in Kabul, where they are successful merchants and craftsmen, they also have strongholds is northern Afghanistan and in the Panjshir Valley north of Kabul. Ahmad Shah Massoud, who was assassinated in 2001, was a native son of this valley. Ismail Khan, who ruled Herat for years, is also Tajik.

Hazaras are the third-largest ethnic group, at 20 percent of the population. We come from the central highlands and call our area, where we have lived for centuries, Hazarajat. We consider ourselves to be the originals—the native population of the country. We have always played a role in defending the country, including against the British and USSR invasions. After the withdrawal of the USSR and the collapse of the regime supported by them, the Hazara leader Abdul Ali Mazari called for equal rights for the people and inclusion of the Hazaras in government. But in the mid-1990s the Taliban declared war on the Hazaras, and the conflict has continued to this day.

The Uzbeks are the fourth-largest ethnic group, at about 10 percent of the population, and are often grouped with the Turkmen ethnic group. They live in the northern regions and developed a reputation as defenders of the country when, along with the Hazaras and Tajiks, they joined Ahmad Shah Massoud and the Northern Alliance and fought against the Taliban regime. When the Taliban was defeated, the Uzbeks took their place as some of the influential military and political leaders in Kabul.

A collection of about a dozen other ethnic groups make up the remaining 5 percent.

The Pashtuns, Tajiks and Uzbeks are all Sunni Muslims. We Hazaras, who make up one-fifth of the 38 to 40 million Afghans, are mostly Shi’ite Muslims, but some are also Sunni. (The Shi’ite religion was not officially recognized until the adoption of the nation’s new constitution in 2004.)

The rich historical past of the Hazaras has contributed so much to Afghanistan. The capital of our region, Bamiyan, is a mystical place of shimmering poplar groves, babbling brooks and majestic copper-toned mountains where the ancient Buddha statues that were hewn out of the sandstone cliffs stood watch for more than fifteen hundred years. There were two statues: one was 38 meters tall and built around 570 CE; the other was 52 meters tall and built around 618 CE, when the Hephthalites ruled the region. There were many other smaller Buddhas in sitting positions located nearby, as well as in other valleys. In March 2001, the Taliban blew them all up in an act of cultural erasure. The act was perpetrated as theater to appease their hardline foreign supporters and distract from their inability to govern. It was also a convenient way to hide the mass graves that held the remains of those Hazaras who were executed by the Taliban during their takeover of Bamiyan.

During the five long years from 1996 to 2001 when the Taliban was in power, they failed to repair a single road or remove the heaps of rubble that had accumulated in the cities after the nine-year civil war that followed the collapse of the regime supported by the USSR. Nor did they implement any civic improvements such as garbage removal or clean water sources, or basic social services such as health care and education. However, there was one project to which they devoted incredible energy: destroying the ancient Buddha statues.

At first, they used army tanks to fire artillery shells at the icons, but that hardly caused a dent in these enormous structures. Then they planted explosives to bring them down, but that was also to no avail. Finally, the Taliban rounded up Hazara men who they considered to be infidels—and therefore disposable—and strapped bombs to their bodies. The men were forced to climb the Buddhas and plant the munitions in crevices; some of them were even hung from the top of the statues by their feet to make sure the bombs were strategically placed. The detonators from the bombs were wired and laid all the way to the mosque where the Taliban activated them, bringing more than fifteen hundred years of history to a thundering end while the onlookers shouted “Allahu Akbar.” These were the actions of the men who were ruling my country while the world looked the other way.

Whenever I visit Bamiyan, the rhythm of life plays like the sound of a lute. When the sun sets, a quietude takes over that whispers of an enduring past. Frescoes discovered around the Buddha statues suggest Hazaras descended from the people who built them. The entire Bamiyan city was declared a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site in 2003. The declaration was to represent the artistic and religious developments from the first century to the thirteenth century and to mark the tragic destruction of the Buddha statues.

Bamiyan is located on the Silk Road, the network of ancient trade routes that linked China to western Asia. In fact, the route was so well-known for its role in carrying messages as well as goods that the United States Postal Service referenced it in their slogan. The Greek writer Herodotus, referring to the Silk Road noted:

There is nothing in the worldthat travels faster than these Persian couriers.

Neither snow, nor rain, norheat, nor darkness of nightprevents these couriersfrom completing their designated stages with utmost speed.

In recent years, the pride I’ve always felt in the heritage of my homeland has been stained by events that foretell a bleak future. To understand how we got here, we need to look at the root causes of Afghanistan’s struggles. Chief among them may be the conflict between the two separate arms of Islam—Sunni and Shi’ite. The Sunnis make up the majority of the world’s Muslims; the rest are Shi’ite. The differences between the two are like the differences between Catholics and Protestants, or even the differences within each group itself, such as the Roman Catholics and the Eastern Catholics or the Protestant Anglicans and Presbyterians. Or, for that matter, the various sects or branches of Buddhism, Judaism and Hinduism. It’s all about minor interpretations of a religion that has a basic creed for everyone. We all worship the same god. We all believe in the doctrines of goodness, honesty, humility, generosity and service. How we express those beliefs is a personal and spiritual journey each of us takes or decides not to take. And yet religion is used as an excuse to discriminate, to punish and even to kill. Rather than bringing us together in service, one to the other, it drives us apart. Religion is used as a political tool to control people; this happens not just here in Afghanistan but in many parts of the world where strife is tearing civil society apart.

For example, the Taliban are adamant that their version of Islam is the real one, and all those who practice other versions, particularly the Shi’ite, are infidels and better dead. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)—or the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP), as they’re known here—believe in Wahhabism, a strict, puritanical form of Sunni Islam known for its harsh intolerance and ferocity and for its quick judgment of Hazaras as infidels. In fact, as in so many conflicts, various factions use religion to separate and divide people, to isolate and accuse others who choose to be different.

If you examine our history, you can see that our downfall began with the role assigned to women. By creating a culture that excluded women, politicians barred the way to sustainable peace. While the first girls’ school was started by King Amanullah Khan in 1920, later, during King Mohammad Zahir Shah’s reign, schools for girls were established in different parts of the country. And although numbers were small, there was a female presence on the police force and women were part of the government, even serving as cabinet ministers. I am a product of that time: I studied in a coeducational school in the country’s southern province of Helmand, where I spent my childhood in the sixties and seventies.

In 1973, Mohammad Daoud Khan seized power from the longtime monarch and the country began to change. Although Daoud was ultimately tossed out in 1978 by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), a Marxist-Leninist group that paved the way to the Soviet invasion in 1979, the government had already started violating our human rights and restricting our freedom. For example, the pro-Soviet PDPA regime set a limit of just three hundred Afghanis (about ten dollars in US currency at that time, or about 11 percent of an average monthly salary in Afghanistan) for a woman’s maher, an amount that is paid to the bride (the maher is not the same as the bride price, which is paid to the family). The maher, which had previously been as high as four thousand or even five thousand Afghanis, had provided some economic security for a woman getting married, since she didn’t receive much from family wealth. The regime’s new law exacerbated women’s insecurity, and became a source of insult. I experienced it personally as a student at Kabul University’s Faculty of Medicine; male peers would offer lewd jokes suggesting they could purchase each Afghan woman for about three hundred Afghanis. And some would say, “Look, I have six hundred Afghanis—I can buy two of you.” The new law objectified women and further eroded their status. However, that was only the start.

It took a troika to entrap the women of my country: the mujahideen, the Americans and the Saudi Arabians. First, mujahideen factions, which were the main resistance to the communists, chose Islamism as their political ideology, probably because the Islamic ideals of the Muslim Brotherhood were spreading rapidly throughout the Middle East, and because Iran had already chosen a religious national leader. As well, in neighboring Pakistan, President Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq had turned to Islamization.

Second, the Americans got involved. Zbigniew Brzezinski, the national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter, made use of Islam as a weapon of war in Afghanistan to create a counter force to defeat the occupying government of the USSR. He instructed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to provide military supplies and humanitarian aid to the mujahideen, who were now branded as Afghan freedom fighters. In fact, although the West was taken up with the romantic notion of freedom fighters, the aid being sent was tailored toward militarizing the mujahideen to fight what would become a proxy war between the US and USSR. Ignoring Pakistani president Zia’s dismal human rights record and his Islamization policy, the Americans entered a close political relationship with Zia. By January 1980, the month Ronald Reagan became the US president, lethal arms began arriving in Pakistan for use in Afghanistan. Financial and military support to the mujahideen increased dramatically.

Third, Saudi Arabia was brought into the picture because it was willing to match American funds for the mujahideen. For the Saudis, this was a unique opportunity to gain influence in the region and import Wahhabism, their anti-woman brand of ultraconservative Islam.

The mujahideen, who received funds funneled through Pakistan from the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, China and several Arab countries, employed a politicized Islam as a means of fighting communism and selling their vision of Afghanistan to the broader population. How did they do this? Easily, by insisting they would ensure the safety of Afghan women. Under the guise of protecting women from foreign thugs, they wanted us cloistered behind purdah and walls that restricted our participation in society. This so-called protection of Afghan women is an argument that has been used by different regimes during forty-five years of war and continues to be used by the Taliban today.

After the Soviets ended their ten-year military occupation of the country in 1989, the international community assumed the Cold War was over and took off like a school of minnows. The result was a power vacuum contested by seven different factions of mujahideen, whose headquarters were in Pakistan—as well as the other groups in Iran. A fratricidal bloodbath erupted.

The mujahideen vowed they would return Afghanistan to its rich past by honoring Islam; they recalled how pro-Soviet occupiers had desecrated our culture by walking inside mosques with their shoes on or by beating a mullah and telling him to call on his God to come and save him. To gain public support, each faction one-upped the other when it came to how strictly the religion would be followed and how true to the ancient cultural traditions they would be. The result was that the status of women steadily declined as the mujahideen stripped their rights one by one, all the while claiming they were ridding the country of Soviet influence.

In fact, their goal wasn’t to restore honor but rather to seek power in an internecine battle for control characterized by extraordinary brutality and lawlessness. It was a battle that brought the country to its knees and scorched the emotional earth of its citizens. For example, in 1993, not far from the neighborhood where the Hazara school girls were murdered at the Sayed Al-Shuhada school, the mujahideen were on a rampage. Warlords and their militia from different groups led raids on houses, looking for money and gold and kidnapping young men for ransom. The militia beat people to death, stole whatever they wanted, and even killed babies; they, too, demanded money, gold and jewelry. One woman was told to give them her gold wedding ring, and when she struggled to get the ring off her finger, even licking the skin around the ring to urge it away, the wretched brutes watching became peeved with the wait. They splayed her fingers apart and chopped one of her fingers off with a bayonet. When the ring tumbled to the ground, they scooped up their piece of gold and left. These atrocities were happening across the country, but the Hazaras got the worst of it. The fighting and the destruction, especially in the west part of Kabul, was brutal for all sides, and international laws of war were ignored.

Of the mujahideen groups vying for power, it was the extremist Taliban who came out on top. It began with their takeover of Kandahar in 1994 and continued with a march across the country; they defeated other factions along the way and arrived victorious in Kabul on September 27, 1996. These young men had been schooled in madrassas opened for Afghan refugee children in Pakistan—Taliban means “students”—but the curriculum was misinformation and hatred, and they were otherwise mostly illiterate. They promised peace, but in reality they hijacked Islam for political opportunism to deliver a toxic mix of misogyny and misery, all in the name of God.

Before the Taliban—and, in fact, before the civil war began—a tactic known as the night letter had begun to be employed. The original purpose of the letters had been to increase awareness, and to call on people to join protests. But the Taliban used night letters to intimidate and spread fear. Usually unsigned and distributed by hand in the dead of night, the letters would be nailed to a household door, a tree, a mosque, or simply tossed over a boundary wall. The letters invariably contained instructions or demands, with threats of dire consequences for failing to obey. News of the threat invariably traveled rapidly to the whole community—an efficient way of spreading terror and exerting control.

After their defeat in 2001, the Taliban continued their nocturnal postal activities, sending letters to anyone seen as supporting the government or the international community. In the face of such unwelcome threats, people rarely went to the police. In most cases, individuals assessed the seriousness of the threat themselves and took precautionary measures on their own, such as relocating.

These night letters are a microcosm of my country—a country in which hidden puppeteers hold the strings of the people and make them dance with fear: first this way, then that way, swaying in whatever direction the puppet master chooses. Some night letters, like the ones delivered during the pro-Soviet regime, succeeded in ridding the country of people who didn’t respect our culture and religion. Others, like the ones from the Taliban, have prevented the elected government from taking our country into the twenty-first century. Plain as it is, just a scribble on a scrap of paper, the letter carries a mighty message. This underground networking is woven into the fabric of this land as a history of intimidation, a threat, and a way of reaching an entire village with one piece of paper nailed to a door. Violence is therefore predictable and recurs.

In fact, the same community where the attack on the school occurred in 2021 has also been the site of horrendous atrocities. Almost exactly a year before the attack, on May 12, 2020, a gang of assailants stormed into a maternity ward run by Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) at the Dasht-e-Barchi Hospital and killed twenty-four people, deliberately targeting newborn babies, mothers, and women in labor. Among those killed were fifteen mothers and an MSF midwife, Maryam Noorzad. The attackers also killed two young children and six other individuals who happened to be in the hallway.

Because these terrorist attacks are not new to our people, many public buildings have created what we call safe rooms where people can hide. On that day, about one hundred people found shelter in the safe rooms of the hospital, including one woman who gave birth to a healthy baby in the midst of the terror attack. Others weren’t so lucky. MSF sent out a press release that said, “Mothers, babies, and health staff were deliberately targeted. While the identities of the assailants remain unknown, this horrific crime appears to be part of a larger pattern of attacks targeting the ethnic Hazara community living in the area.”

I wondered about the men who committed this crime and how they would celebrate their victory against women with their feet in stirrups on the delivery table and an army of newborn babies wrapped in blankets. To murder women while they deliver babies in a maternity ward and claim they are doing so to serve Allah is, for civilized people, an incomprehensible stretch.

Just a year later it was schoolgirls who were singled out for death. Several days would pass before the police and the media pieced together the awful events that resulted in the death of ninety-five schoolgirls, and the injury of more than two hundred. My heart ached for the mothers who were running from one hospital to another, checking every injured child, every dead body, one by one, hoping against hope to find their own girl alive. The hospitals and clinics were so overwhelmed that it was several days before they had lists of the wounded or the names of the dead.

Those bright-eyed little girls had made such an easy target because the school was so crowded, often having between fifty-two and sixty children in a class. And because security had been such a problem in the district, they dismissed the students in batches, the youngest first, then the middle grades and finally the seniors. The four explosions were carefully planned and executed to coincide with the hour the middle-grade girls—most aged twelve to seventeen— were dismissed.

I often ask myself what these men who target the poor, who seek to improve their lot in life at the expense of others—especially women and girls—are afraid of. Is it change? A man once said to me, “If I give women human rights, I have to give away my human rights.” I tried to explain the concepts of equality and fairness and justice to him. I tried to help him understand that dozens of studies have shown that human rights are for all people and are a key to prosperity, to better outcomes for everyone. But he could process only the “giving away” part and stubbornly clung to his point of view. Eventually, I seemed to get through to him.

As day became night on May 8, the horrific scenes kept replaying in my mind. The same questions circled my brain like the whir of a wheel: When will this end? What can we do to tame the terrorists? When night came, I turned out the light hoping for relief, but those girls stayed with me; their faces played on the back of my eyelids and came to me in nightmares that left me weeping until the dawn.

Conflict in Afghanistan reveals a lot about governments and militaries around the world. Old concepts like the Geneva Conventions are no longer followed. What exactly is “the war on terror”? What do we actually mean when we speak of “endless war” and “perpetual war”? Humanitarian law and war are a contradiction in terms, and yet we pursue both.

And what happens to people during this period? We know conflict destroys buildings and bridges and that it kills mothers and fathers and children. But it also damages the way we act as citizens. Our behavior is shaped by the fear and anger and unpredictability that war brings. How can we imagine that forty-five years of war, and in particular the last eighteen years of suicide bombings and improvised explosive devices and attacks on our public institutions, will not contribute to emotional instability in Afghanistan?

The people are caught between the extreme left (communism) and the extreme right (Islamic fundamentalism). They’re in the middle, with justice and peace up for grabs. I’m fascinated by how much we study war, analyze war, make movies about war and write about war, and yet never find the formula to stop it. That suggests to me that we’ve been looking for peace in the wrong places. Most wars today are civil wars. They are about insurgents and terrorists, usually rogue leaders and people who follow them blindly.

Historians say war has become easier to start and harder to stop. They also say Afghanistan will likely be the last international intervention that includes foreign boots on the ground. This is a possibility that all of us, not just Afghans, need to examine, because there are consequences for everyone. War is so destructive to human relationships; it makes even ordinary people resort to violence. In Afghanistan, and in every other war-torn country, poverty increases, and it is children, people with disabilities and women who get the worst of it. I remember seeing a child on the street during the first Taliban takeover; he was screaming his head off and all alone. The smoke from a bomb in his village was still rising. It was just one of many stark examples of how the suffering of children is part of the tapestry of conflict.

In war’s aftermath the people are yoked to its consequences. Most suffer from the psychological trauma that comes with insecurity; others—the homeless ones, the orphans, the wounded, the malnourished—suffer no less grievously. All of them are paying the price for someone else’s feud, and without help they grow up and keep the war kettle boiling, carrying the quarrel to the next generation.

And where does it end? It ends in places like the Hills of the Martyrs, a field with mudbrick houses scattered about that has become the resting place of the girls from Sayed Al-Shuhada school, the moms and babies from the Dasht-e-Barchi Hospital, and so many more from different attacks. I often ask myself why grandiose cast-iron statues of men on horseback with guns raised triumphantly are the monuments of war in the city centers of the world, while the blameless victims are buried together in cemeteries far away. Traditionally, when people died in the city their families took them back to the region they’d come from to bury them with their ancestors. But the increase in terrorist attacks in the west end of Kabul has moved people to claim the two rock-strewn dusty hills behind the school as a cemetery.

The cemetery came to be in July 2016, after an attack on people who were peacefully marching to demand a newly built electricity line to supply their neighborhood. Suddenly, the government had soldiers and barriers on the road that blocked the marchers’ way to the city. Hundreds of men, women and even children were stopped and trapped in the middle of the road—a perfect target for the suicide bomber looking to strike. More than three hundred were injured, and eighty-six people died, most of them young boys and girls. It was decided to honor them as martyrs and to bury them on the hills not far from where they died. The government tried to stop this, but the voice of the people rang out louder than the grumbling of the politicians.

Suicide attacks had been rare in Afghanistan until 2006 but have since increased every year, influenced by jihadis outside of our country who began targeting mosques, sports clubs, wedding celebrations and election centers—wherever people gathered in large numbers. And the victims were mostly children dreaming to build a civilized, democratic Afghanistan. They found peace on those two little hills on the west side of Kabul.

While there had been other attacks, and children had been killed before, the May 2021 assault on girls leaving their school was like a rumbling coming from the core of the earth. It told all of us that inhumane terrorist killings were picking up speed. Even religion wasn’t slowing the attackers down—the Taliban spokesman had warned: “Jihad during Ramadan is more valuable in the eyes of God the Almighty!” Although the Taliban claimed not to be responsible for the attack, the terrorist factions are interconnected: the Taliban, ISKP, and other bloodthirsty groups—all know what the other is up to.

The truly perplexing thing about all of them is that women and education are their Achilles’ heel. Consider this: Between 1996 and 2001, women, who represent 50 percent of the population, were treated like slaves and like baby-making machines (and the more male babies, the better). Women could not speak out or talk back—they had no rights and lived obediently and submissively at home, suffering no end of violence. In 2001, when the Taliban was defeated, a lot of that changed; for the next twenty years, girls could go to school and become lawyers, journalists, governors, ministers, members of parliament, senators, teachers, doctors, entrepreneurs, artists and sportswomen. The universities were crammed with girls and boys who were reaching for the stars and imagining lives of fulfillment and success.

The young women had been joining the workforce as executives, and the government as ministers, and the judiciary as judges. In August 2021, they were even on the negotiating team that went to Doha, Qatar, for discussions with the Taliban to find a way to end the years of conflict. What’s more, today 64 percent of Afghans are under the age of twenty-five. The Taliban may try to take their rights away, but they cannot erase the knowledge of the majority of its young citizens.

As summer began in 2021, many here were very afraid. So was I. We had stopped trusting the foundation on which the progress of the last two decades had been built. I kept reminding myself to look at what we’d accomplished: the institutions we built, the human rights record that’s in progress, women taking their rightful place beside men in government and business, a flourishing media. After all that, after building and facilitating a democracy, imagine losing it all again. That is a loss not only for Afghans but for all people and countries who believe in human rights and democratic values.

I know the inside story of my country––the hijacking of the religion, the dishonesty, the collusion, the corruption, the self-serving leaders. I know the courageous women and men who have lifted the country to heights we had only imagined. And I know the blameless ones who simply want peace and a chance for their children’s future. I have been an eyewitness to the US effort, to NATO’s work, to the UN, the international community, and our own military. I know the players in this chess game called Afghanistan.

As a woman and physician, as a politician and activist, as a human being who has spent a lifetime witnessing one paroxysm of violence after another, I can say this: The hopes and dreams of the girls at Sayed Al-Shuhada school were the same as mine. Those girls perished simply because they were girls, because they dared to go to school to learn to think for themselves. They are my story. And I was their age—twelve—when I became aware that my country needed change.

Two

GIRL CHILD

THE SCENT OF FRESHLY BAKED BREAD wafting through a room has a way of tying each of us indelibly to a place. For me, that place is my home in the central highlands of Afghanistan, in a village called See Paya, in the district of Jaghori, in the province of Ghazni. Every nook and cranny is stored in my memory like a time capsule. We referred to dwellings like ours as muddy houses, as they are made from mud with straw, twigs and bits of small tree branches mixed in that is then packed around wooden poles. In the tunnels built under the floor and attached to the underside of the oven my mother used to bake what we call naan bread every single day. The smoke from the fire would spread, along with the scrumptious scent of the baking bread, through the tunnels that brought heat and a sense of sanctuary to the rest of the house.

An Afghan house is like an Afghan family—extended and sometimes complicated. Our house was attached by a corridor to my uncle Ali Asgher’s house. It was a bigger house than his and more modern, with a few more windows and a second floor, which I presumed was because my father had worked outside the village and had seen other homes built this way before he built our house on the side of his brother’s place. The flat roof was used during the summer months to dry apricots, mulberries, and almonds and to drain the yogurt and shape it into balls of qurut, used to thicken soups and other dishes. Most muddy houses had one small window to let the light into the main room and keep the winter cold and the summer heat out of the other rooms. Ours had three large windows facing south, which served both requirements—the heat of the sun poured into those rooms when it was cold, and we could read and do our stitching by its light all day long. The cooking room that my mother used in the winter months had a small alcove off to the side that we used as a private and warm place to bathe. In the summer, the cooking was done outdoors; whether inside or out, vegetables and meat were cooked over an open fire and milk was gathered from the livestock to be boiled into yogurt, butter and cheese. But no matter the season or the weather, the daily aroma of baking bread lingered— summer, winter, all day—and that memory stays with me and nourishes my soul.

The main room in the house where the family gathered was lined with mattresses and cushions and had no furniture. We sat on these pads on the floor around the dastarkhan—a large rectangular oil cloth—to eat our meals. The food was served on heaping platters and in bowls in the center of the dastarkhan, and everyone helped themselves to a meal that we ate with our hands. We also slept on the floor; there was not a lot of furniture in an Afghan house where I grew up. The mattresses, pillows and quilts were piled up in one corner of the house during the day in a stack called the bars. We each had our own bedding, but there were always extras for any guests.

Although we didn’t have anything in the way of riches, I somehow knew we were a little better off than the others, partly because most muddy houses were smaller than ours and didn’t have large windows, but also because the whole village used the services of one shepherd to graze the goats and sheep, but our family had a shepherd of our own. Aside from the kitchen and sitting room that made up the main part of the house, two stables were attached to the back: one for the cows and donkeys and another for the sheep. Those rooms, which brought welcome warmth to the house in the winter months, led to the courtyard, and that’s where the shepherd would be every day at dawn to care for the animals. As soon as the weather allowed, he would collect a lunch of yogurt and naan bread from my mother and herd the animals into the hills for grazing. I loved watching them, especially during the first days of spring when they would lift their heads high and make snorting noises in anticipation and nearly run to the trodden paths, knowing that the sweet green grasses had pushed through the earth and were waiting for them after a long winter spent cooped up in the yard with only dried grains to eat. The shepherd brought the animals back down to the courtyard in time for the women to milk them before the evening meal. Day in and day out, these were the rituals that marked my early years.

Our house had no running water or electricity. What’s more, it didn’t have my father. That’s the complicated part. My father, Qadim Ali Yaqubi, lived in a modern house about 550 kilometers away in Lashkar Gah in Helmand Province, with his second wife, Halima, and their children. He had a job as an accountant at Helmand Valley Development, which was a project funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to better manage the availability of water in the valley. Although my father never had formal schooling and learned to read and write with the mullah in Jaghori, I always thought his success as a respected accountant spoke a lot about his intellect as well as his ability.

When I was very small, we’d all lived together in Jaghori: my sister, Aziza, nine years older than me; my brother, Abdul Wahid, six years older; and two children my father had with Halima at that time. They eventually had seven more for a total of nine children, which, when added to the three from my mother, made us a very large family. I was a toddler when my father moved away with Halima, so I don’t remember the details. But it wasn’t particularly unusual, as it was common for the male member of the family to be out of our district to find work. Aziza and Abdul Wahid left with them; Abdul Wahid would have more educational opportunities outside of Jaghori. One of the reasons my mother and I stayed behind was a matter of family business. My father and his brother owned the land, the livestock and the business they did in Jaghori together. My mother needed to manage and assert ownership of my father’s side of the properties while he took a new job in Lashkar Gah.