Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

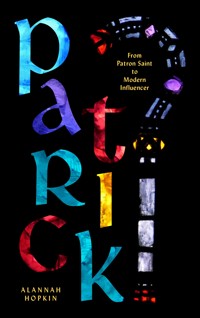

St Patrick is one of the most famous saints of all time. Thousands of people with no direct Irish connection celebrate St Patrick's Day, parading along the streets of New York, Boston, Chicago, San Antonio, Texas and Sydney, where St Patrick's Day is a national holiday. These celebrations are the latest version of the cult of St Patrick, which has persisted in different forms since his death on 17 March, 462AD. But who was St Patrick, and how much of what we know about him is fact, how much legend? This book looks at the historical man and the evidence of his writings, the myths and the apocryphal stories, and describes the social changes that led in the 18th century to his emergence as a symbol of Irish nationalism. Patrick: From Patron Saint to Modern Influencer is a fascinating and lively portrait of the man who converted pagan Ireland to Christianity – a fresh, sometimes startling examination of the folklore and traditions that have developed around the saint through the ages. First published in 1989 in the UK and USA, this fully updated edition features new photographs and illustrations and will be an indispensable companion for anyone seeking to understand the role of St Patrick in forging modern Irish identity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PATRICK

PATRICK

Second edition published in 2023 by New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

First edition published under the title The Living Legend of St Patrick in the UK by Grafton Books and in the USA by St Martin’s Press, 1989.

Copyright © Alannah Hopkin, 1989, 2023

The right of Alannah Hopkin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-888-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-889-0

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Set in Adobe Jenson Pro in 10.5 pt on 16 pt

Typeset and Cover Design by Niall McCormack, hitone.ie

Edited by Meg Walker

Indexed and Proofread by Jane Rogers

Printed by L&C, Poland, lcprinting.eu

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

1. EgoPatricius

2. The Earliest Lives and the Lecale Peninsula

3. The Tripartite Life and Croagh Patrick

4. The Norman View and Downpatrick

5. St Patrick’s Purgatory: Lough Derg

6. The Greening of St Patrick

7. St Patrick’s Day

8. Although it is the Night

9. The New Irish

Appendix I: The Writings of St Patrick

Appendix II: Muirchú’s Miracles

Notes

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements – 1989 Edition

Photography Credits

Preface

When I originally wrote this book in 1987 I had carried an Irish passport for barely ten years. Born in Singapore to an English father and an Irish mother, who, being born before 1948, carried a British passport, I was naturally considered British. We lived in London, but in my late twenties I decided to swap my British passport for an Irish one because I intended to move to Ireland, to live by the sea in my mother’s home town and make my living as a writer. I felt more at home there than I did in London, and longed for a more outdoor life than I could have in Soho, where I was living. I had a choice. In contrast, my mother left Ireland in 1931 with her sister to qualify as a nurse-midwife in London because, as she used to say plaintively, ‘There was nothing for us in Ireland.’

I made the move in 1982, and by 1985 I had published two novels, neither of which had sold well. My London publisher did not want a third novel, especially not a third novel about eighteenth-century West Cork. I was writing it anyway, while also taking on whatever journalistic work I could find in those pre-internet days. I soon realised that, having been to school in England, I did not know enough about Irish history to write the novel, and I was quickly running out of money. Even worse, I was not enjoying life in Ireland as much as I had expected. People reacted badly to my English accent, and only dropped their hostility once they learnt I had local connections. When I admitted to having an English father and an Irish mother, I was then asked, ‘But where were you born?’ as if that would clinch it. The answer – Singapore – was no help. In London, I had been ‘othered’ as ‘mad Irish’; in Ireland, I was being rejected as English. Who was I and where did I belong?

This was the point at which my agent suggested that I write a book about St Patrick. Grafton Books was offering good money, and it could probably be done in six months. My financial problems would be solved, and the research would involve a crash course in Irish history, which would help enormously with the historical novel. There had to be more to Irish history than the narrow, sectarian story of 800 years of British oppression, and I was determined to discover the wider picture. St Patrick was an excellent starting point. My plan was to follow the figure of St Patrick down the ages, and discover how the name of a humble and austere missionary had become synonymous with drunkenness, partying and disorder. Also, by finding out who St Patrick was, perhaps I would also find out who I was.

In the end, the book took eighteen months to research and write. It was well received both here and in the US, but it did not make my fortune. (Neither did the historical novel, but that is scéal eile). I had mixed feelings about the book because my working title, St Patrick and the Irish People had been rejected in favour of The Living Legend of St Patrick. I hated the fake concept ‘Living Legend’, and also disliked the book’s design and illustrations.

I continued to work as a writer and journalist, publishing several non-fiction books, a collection of stories and a memoir, and the years flew by. Then new friends, who had not read the book when it first came out, started tracking it down, finding it interesting, and asking me why it was no longer in print. I had recently had a book published by New Island Books, so I asked if they would be interested in a reissue, and the answer was yes.

The original book has been very lightly updated, as it mainly features descriptions of historical texts which have not changed. But Ireland has changed, and hugely for the better, and so have the Irish people. We have changed from a drab, repressed country with a declining population where emigration was the main option for the young, to a prosperous, self-confident, multi-racial European nation. That is not to suggest that Ireland is free of racism, at all levels of society, alas. After so long in isolation, there has inevitably been tension at the influx of new faces. But as time passes, and people get to know each other, racist behaviour is seen as the reaction of an ignorant minority and not to be tolerated. Many people who have settled in Ireland enthusiastically take up the option of full Irish citizenship, greatly enriching both the cultural and the economic landscape. I especially hope that those who have come from other countries to find their home in Ireland will find the role of St Patrick in forming the island’s identity an interesting one.

Introduction

Many volumes have been written about St Patrick and his life. This book is more concerned with the images of St Patrick held in different ages, and their significance, than with the saint himself. St Patrick has become associated with a particular national stereotype which many Irish people detest. Garrulity, sentimental religiosity, quaintness, deviousness combined with naivety – its very name is derived from the saint himself: Paddywhackery.

Rejection of this stereotype in modern Ireland has been accompanied by a decline in interest in St Patrick, which has probably never been at a lower ebb. This is, however, in a way a positive development, as it also represents the rejection of the many bogus traditions and superstitions that have become associated with the saint during the long history of his cult.

St Patrick did indeed exist, but the scant facts available about his life did not become common knowledge until the twentieth century. Many people still confuse the St Patrick of legend with the very different historical figure. Early Irish society rewrote St Patrick’s life as that of a secular hero. In medieval times his life was rewritten again, this time to conform to the continental idea of sainthood. The modern image of St Patrick started to emerge in the late eighteenth century, when he was adopted as a symbol of the nationalist movement. The various ways in which he has been presented over the centuries must be understood if the historical St Patrick and his legacy are to be disassociated from Paddywhackery.

St Patrick does not only belong to the Irish who have stayed at home. The Irish abroad and those of Irish descent around the world have made 17 March an international occasion on which the Irish and their friends celebrate his name. The way in which they do so is often criticised, particularly for its emphasis on alcohol, but even this apparently irrelevant association has a long history. In New York millions of people watch a highly organised parade lasting some six hours make its way down Fifth Avenue. In San Antonio, Texas, they dye the river green. Parades are held as far afield as Alaska, Puerto Rico, Montreal and Sydney, Australia, celebrating a kind of Irishness that would hardly be recognised in Ireland itself, and yet originated there.

The search for St Patrick is not only a geographical one, although I have described many of the sites and pilgrimages in Ireland associated with the saint. It is also a historical search, which travels down the centuries through the social, cultural, intellectual and spiritual life of the Irish people. It begins by outlining the little that is known about the historical St Patrick, a Romano-British bishop of the fifth century.

Ego Patricius

Ego Patricius peccator rusticissimus et minimus omnium fidelium et contemptibilis sum apud plurimos.

I am Patrick, a sinner, most unlearned, the least of all the faithful, and utterly despised by many.

o begins the Confession of Patricius. There is no doubt as to its authenticity. Over the years scholars have disputed just about every aspect of the story of St Patrick, but no one has ever credibly argued that his Confession was faked. It is too clumsy, too vague and too idiosyncratic to be the work of a forger.

The difference between the St Patrick of legend and the author of the Confession is so great that St Patrick will be referred to as Patricius throughout this chapter. It is hoped that this device will help to extricate the historical man from the accretions of legend.

Patricius wrote, or perhaps dictated, the Confession in Latin when he was an old man. The other surviving piece of writing by Patricius is his Letter to Coroticus and in this he tells us in no uncertain terms: ‘With my own hands have I written and composed these words.’ Taken together, the two texts provide us with a tantalising picture of the man Patricius. His firm, straightforward character lives in his words. There can be no doubt of his sincerity, his humility and his steadfastness. But, as one of those scholars who has dedicated his life to the study of these texts has written: ‘We would wish their author were as lucid as he is sincere.’

Patricius’s Latin is rough, to put it mildly, and he points out more than once that Latin was not his normal daily language. But it is the very imperfection of his writing, the feeling that he is often fumbling for words, falling back on biblical quotation when all else fails – he uses over 200 of these – and breaking into spontaneous prayer, that brings Patricius so much alive as a man. Augustine, who was writing his Confession in Hippo a generation before Patricius wrote his in Ireland, is a far more accomplished rhetorician, but we see Augustine as he wants us to see him. Patricius is incapable of manipulating his readers in that way: the man comes alive in his halting but moving prose.

The Confession was written in the middle of the fifth century. That is a remarkable feature in itself: it is the only autobiographical writing surviving from those years in British or Irish annals. A highly individual voice is speaking to us from across the centuries. And, moreover, it is the voice of one of the great saints of the early Christian church, the voice of Patricius himself.

To understand more fully the scholarly excitement generated by the Confession, it is important to appreciate just how little is known about Ireland and Britain in the fifth century. Pick up any respectable and serious (as opposed to speculative) work on early Irish history and you will find a veritable thesaurus of apologiae for ignorance: ‘nothing is known of …’, ‘… remains impenetrably obscure …’, ‘the scanty surviving evidence suggests …’, ‘hardly less obscure is …’, ‘… presents an insoluble problem …’ Professor Gearóid Mac Niocaill, who generated all the above phrases in one short chapter of his excellent standard history Ireland Before the Vikings, manages to be sure of something at least when he writes: ‘The fifth century has been very justly described as a lost century.’ Professor Charles Thomas, another authority on the period, confirms this: ‘The fifth century continues to be the most obscure in our recorded history.’ The eminent Irish historian D. A. Binchy, introducing his readers to the period, makes his point by the grand gesture of quoting the closing lines of Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’ as a metaphor for the historian faced with the task of making sense of the fifth century:

St Patrick’s Bell and Shrine

The only relic among the treasures associated with St Patrick in Dublin’s National Museum of Ireland that actually dates from the fifth century is this iron bell. Even if it is not, as is traditionally believed, the bell used by the saint, he probably carried one very like it. The beautiful artefact on the right was made to enshrine the bell in the late eleventh century. The interlacements on the front are of gold, those on the sides of silver. © National Museum of Ireland. This image is reproduced with the kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland.

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

In fact much of the little that we do know about the fifth century is due to the labours of the Patrician scholars, as those who have made a serious study of the life of St Patrick are called. That Patricius himself is a major source for the period only adds to the confusion, as there was, until very recently, little external evidence to shed light on his difficult writings. Consequently, up to about twenty years ago, historians of the fifth century in Ireland tended to concentrate largely on the Patrician texts. Mac Niocaill is understandably rather scathing about this tendency: ‘The problems of St Patrick’s chronology and mission have largely occupied the attention of the few concerned with early Irish history: not unnaturally, since they afford splendid opportunities for conjecture and abundant scope for the exercise of academic spleen.’

Irish historians refer to the fifth century in positive terms as ‘early Christian Ireland’. The British used to call the same period ‘the Dark Ages’. In Ireland the fifth century marks the end of the Iron Age, the end of centuries of isolation and the start of the island’s entry into the historical world. In Britain the fifth century is a retrograde phase permeated by the darkness which attended the fall of the Roman Empire. It was the age in which the social and political structures of Roman Britain were falling apart.

With the exception of Ireland, it was a time of turmoil for the whole of the western world. Barbarians penetrated even into Italy. In 407, Gaul was invaded by a Vandal horde and Alaric and the Goths sacked Rome. In the middle of the fifth century Attila and the Huns overran what was left of the empire. The Romano-British were at the start of what was to be a losing battle against the Saxons.

Roman Britain did not disappear overnight: it fell apart gradually. Britain had been under Roman occupation for three and a half centuries, and whatever the state of political disarray in the country, in the early fifth century people like Patricius still considered themselves to be Roman Britons, Christians, and intrinsically superior to the marauding barbarians around them.

The full text of the Confession and the Letter to Coroticus will be found in Appendix I, but, standing as they do alone among British and Irish documents of the time, they cannot simply be left to speak for themselves. A commentary is needed. In order to allow these writings to give a picture of Patricius as he presents himself, I will attempt to steer a non-controversial course through the accumulation of learned commentary on his texts.

There are about a dozen extant manuscripts of the Confession, the earliest of which is contained in the Book of Armagh. This was copied by Ferdomnach, the Scribe of Armagh, who died c.845. The other manuscripts were preserved in English and continental libraries and date from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. Problems arise because Patricius wrote the Confession and the Letter to Coroticus for reasons of his own, and those are not the same reasons why we read them today. We want to know when and where he was born and brought up, where he was ordained, what Britain was like when he left it, what Ireland was like when he arrived there, and so on.

Both the Confession and the Letter were written when Patricius was well established in his Irish mission. The Confession is a reply to certain detractors who had been suggesting that Patricius was neither learned nor competent enough to hold the office of Bishop of Hibernia. It is of a later date than the Letter to Coroticus, but probably not much later.

Patricius sent a letter to Coroticus because, although nominally a Christian, Coroticus had raided the Irish coast and slaughtered or taken captive a batch of newly baptised Christians, with ‘the chrism still gleaming on their foreheads’. Any information that Patricius gives about himself in the course of the ensuing tongue-lashing is entirely incidental.

In the Confession, Patricius is writing for people who know a great deal about him already, and only mentions his life history to stress that he was a freeman of noble birth, and to explain his lack of formal education.

More problems were caused for scholars until quite recent times by the rustic Latin that Patricius uses. It is now accepted that Patricius was not writing bad classical Latin: he was writing Latin as it was spoken at the time. His style is that of the spoken language, not that of literature – the exact opposite of the practice of his continental contemporaries. Moreover, it is not his daily spoken language: Patricius used far more Irish than Latin in his Irish mission. His Latin, besides being rustic, is also decidedly rusty.

The Book of Armagh Facsimile

There is a version of Patrick’s Confession in the Book of Armagh, one of the treasures to be found in the library of Trinity College Dublin. It was copied from the original by the scribe Ferdomnach in Armagh c.807, well after Patrick’s death c.461. In 1937 there was great excitement among the general public when the ancient manuscript was ‘debound’ and each full page photographed, and published by the Stationery Office, Dublin in an affordable edition with an introduction by Edward Gwynn.

He was, apparently, a man who did not write any more than he absolutely had to, although it is easy to gather from these two texts that he must have been a powerful preacher. He is well aware that his Latin is below the standards of the people he is addressing – ‘you men of letters on your estates’. But, time and again, he stresses that he is not being presumptuous by taking it on himself to convert the Irish. He is indeed the most unworthy of all men, but he cannot help what he is doing because God has chosen him for the mission.

Before extracting what there is in the way of biography from the Confession and the Letter, it is worth taking a few minutes to read an extract from the Confession in Ludwig Bieler’s translation, which succeeds in conveying the rather stumbling and clumsy way in which Patricius expresses his thoughts:

For this reason I long had in mind to write, but hesitated until now; I was afraid of exposing myself to the talk of men, because I have not studied like the others, who thoroughly imbibed law and Sacred Scripture, and never had to change from the language of their childhood days, but were able to make it still more perfect …

As a youth, nay, almost as a boy not able to speak, I was taken captive, before I knew what to pursue and what to avoid. Hence today I blush and fear exceedingly to reveal my lack of education; for I am unable to tell my story to those versed in the art of concise writing – in such a way, I mean, as my spirit and mind long to do, and so that the sense of my words expresses what I feel …

Whence I, once rustic, exiled, unlearned, who does not know how to provide for the future, this at least I know most certainly that before I was humiliated I was like a stone lying in the deep mire; and He that is mighty came and in His mercy lifted me up, and raised me aloft, and placed me on the top of the wall. And therefore I ought to cry out aloud and so also render something to the Lord for his great benefits here and in eternity – benefits which the mind of men is unable to appraise.

Wherefore, then, be astonished, ye great and little that fear God, and you men of letters on your estates, listen and pore over this. Who was it who roused up me, the fool that I am, from the midst of those who in the eyes of men are wise, and expert in law, powerful in word and in everything? And He inspired me – me, the outcast of this world – before others, to be the man (if only I could!) who, with fear and reverence and without blame, should faithfully serve the people to whom the love of Christ conveyed and gave me for the duration of my life, if I should be worthy; yes indeed, to serve them humbly and sincerely …

Patricius starts his Confession in a spirit of humiliation – he is a sinner, very unlearned, the least of all the faithful and despised by many. We know from contemporary continental writings that such terms were in most cases pious conventions, but with Patricius they are more than that: he does seem to believe quite sincerely that he is ‘rusticissimus’ and goes to some lengths to explain why one so rustic and unlearned is competent to be Bishop of Hibernia.

Patricius tells us that his father, Calpornius, was a deacon, the son of Potitus, a priest. There was nothing unusual at the time in his immediate ancestors being in holy orders: celibacy was not enforced in the early church. But in the Letter to Coroticus he says that his father was a decurion. This is not, however, as inconsistent as might seem. Decurions were men of property who were allocated the civic duty of collecting taxes in their district, never a pleasant task in any time or place. What made it worse for decurions was that they were personally responsible for the taxes, and what could not be collected had to be made good out of their own wealth. An excellent way of ridding oneself of a decurion’s burdensome chores was to enter holy orders and become a deacon. Hence, perhaps, the reason for Calpornius’s transformation from decurion to deacon.

Patricius then tells us that his father owned a farm or villa (villula)near the village of ‘Bannavem Taberniae’. This is the only clue to the much-disputed matter of the saint’s birthplace. As luck would have it, some scribe along the way, or several of them, miscopied the name. Some scholars reckon it should be ‘Bannaventa Taburniae’, but this is still no help in locating it. Others take the very sensible attitude that, as the village was already unknown by the year 700, when the first biographies of Patricius were being written, there is not much point in quibbling over how to spell it, and no point whatever in trying to identify it precisely until some fresh evidence comes along.

There is no such village on any map of Roman Britain, nor is there any name close to it. There is no other reference to it apart from the one in the Confession. However this has not deterred succeeding generations of Patrician scholars from doing their utmost to identify the birthplace of Patricius. Thirst for knowledge is undoubtedly a good thing, but so is the ability to admit ignorance. The majority of those who take off on a Bannavem Taberniae hunt quickly lose sight of the fact that Patricius never actually says that he was born there, merely that his father had a villa near the place, and that it was while staying at the villa that he was taken captive and sold into slavery to the Irish.

Because Patricius was captured by Irish raiders it seems logical to place Bannavem Taberniae somewhere on the west coast of Britain. The Irish would have been unlikely to raid the east coast, and it is also unlikely that they penetrated far inland. Until very recently there was no archaeological evidence for the existence of villas on or near the north-west coast of Britain at this time, and a location somewhere near the Severn estuary was considered a broadly acceptable solution to the riddle. However, in the past few years, evidence for Roman villas near Strathclyde has emerged, and academic opinion is now favouring the Strathclyde area.

This is how Patricius describes the raid:

I was then about sixteen years of age. I did not know the true God. I was taken into captivity to Ireland with many thousands of people – and deservedly so, because we turned away from God, and did not keep His commandments, and did not obey our priests, who used to remind us of our salvation. And the Lord brought over us the wrath of His anger and scattered us among many nations, even unto the utmost part of the earth, where now my littleness is placed among strangers.

It is important to understand what the move from Romanised Christian Britain to pagan Ireland must have meant for a young man like Patricius. Whatever the state of the continental Empire at that time, Britain was still enjoying the benefits of Roman civilisation. Britain had cities, roads to link them, and Roman-style buildings with the usual amenities: stone walls, paved floors, plumbing, baths and even, in some cases, central heating. We do not know exactly how luxurious Patricius’s home was. His father, being a decurion, was a reasonably wealthy man. Patricius admits to behaviour that one associates in any age with privileged children who do not need to pull themselves up the social or economic ladder by their own efforts – behaviour such as paying little attention to teachers and not obeying the priests. If Patricius’s education (or rather lack of it) was typical of what one scholar calls ‘the jeunesse dorée of his town’, then it is reasonable to assume that his home was fairly comfortable and possessed at least some of the available modern conveniences.

Imagine, then, Patricius’s dismay at being abducted to primitive, pagan Ireland and sent to mind sheep (or to herd swine, as some prefer to believe) on a hillside for an unimportant local chieftain. For a Romano-Briton like Patricius, to find himself in Ireland of the early fifth century would have been equivalent to travelling back in time some 400 years. Patricius must have found the chieftain’s own lifestyle primitive and uncomfortable: no wonder he turned to prayer and penance when he discovered the conditions he himself, as a slave, would have to put up with.

It is in some quarters the fashion in descriptions of early Irish society to emphasise those features of which modern Ireland can be proud – the well-ordered hierarchical structure, the elaborate kinship system, the complexity of the Brehon laws, the rigours of the poetry school, the stirring beauty of the myths and legends, the highly skilled ornamental metalwork, the courage of the warriors and so on.

But we are not interested in the glories of early Irish society here: we are interested in what Patricius saw when he returned to Ireland as a missionary. He saw a country inhabited by pagan barbarians, and was not impressed. He says virtually nothing about native society in his writings, except to make clear that, much as he loves his Irish Christians, he considers his ‘exile’ in Ireland as the ultimate sacrifice demanded of him by God, the price he has to pay for his glorious mission. He sums up the achievement of his mission as follows, with one of the few references to the society he found in Ireland:

Hence, how did it come to pass in Ireland that those who never had a knowledge of God, but until now always worshipped idols and things impure, have now been made a people of the Lord, and are called sons of God, that the sons and daughters of the kings of the Irish are seen to be monks and virgins of Christ?

Patricius learned enough about the Irish social system to exploit its structure for his own proselytising ends (i.e. convert the chief and the rest will follow), but nowhere does he consider the customs of these pagans worthy of detailed description.

It has been said that Irish history dates from the arrival of Patricius. ‘Since the historian depends mainly on written documents for his knowledge of the past,’ writes Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich, ‘Irish history properly speaking must begin with St Patrick, the author of the earliest documents known to have been written in Ireland.’ The use of writing (apart, of course, from ogham inscriptions) only became established in Ireland after the Christian mission had taken a strong hold, so there is no documentary evidence for the state of the country at the time of Patricius’s arrival. Archaeologists have proved that Ireland had been inhabited for at least the previous 3,000 years by an agricultural people. Metalworkers had been around for about 2,000 years, and the Iron Age was about 1,000 years old.

Ireland had been in a state of isolation ever since the (undated) arrival of the Celtic speakers. Not only had Rome left the place unmolested, it had not suffered any invasions by Picts or Germanic tribes either. Ireland was, in effect, totally out of time with continental Europe. What Patricius found was an anachronistic Iron Age society modelled on the Celtic speakers’ social order, speaking a language of which modern Irish is a direct descendant, that is to say, a Celtic language.

The basis of society was the extended family – the tribal unit known as the tuath. There were no towns. The tuath, or small kingdom, was made up of units of extended family plus retainers. They lived in isolated farmsteads defended by a ditch and bank system encircling the dwelling houses. The remains of these ringforts (raths) can be seen today all over Ireland. The buildings within the raths were mostly simple, thatched structures with little to offer in the way of comfort. Outside the ringfort the lower social orders had even simpler dwellings of wattle and turf.

Each tuath consisted of a hierarchical aristocratic community which lived under the protection of its ruler – the rí (king) or taoiseach (chief). There were strata of noblemen below the king. The literati – Brehons, druids and bards – and the craftsmen (áes dána – the gifted people), constituted a separate social class and depended on the nobles for patronage. Below the áes dána came land-owning commoners, and the social scale descended through labourers, serfs and slaves, the lowest of the low being the female slave, whose value was considered equivalent to three heifers.

The main occupation of the tribe was cattle-breeding. There was no coinage: cattle were the main currency and measure of wealth. Because of its bards, its craft traditions and its legal system, early Irish society had a strong cultural unity, but there was no form at all of political unity and certainly no central administration. Some of the tuatha gathered together under a High King, but the office of High King of Ireland was a fairly late development – perhaps fourth century – and seems to have been largely ceremonial.

The Christian monks who, in the centuries after Patricius, wrote down the heroic sagas of oral tradition from which much of our knowledge of early Irish society is gleaned seem to have drawn the line at describing pagan religious practices. This could well be because the pagan Irish did not have much organised religion at all. There are suggestions of sun-worship, and a great reverence for the dead. There were many sacred rivers, streams and wells, some of which archaeologists have identified by the discovery of votive offerings. They held certain gods in awe – Lug and Dagda for example – but we know virtually nothing about how they worshipped them, if at all.

Whether justly or through ignorance of its subtler aspects, the main impression we have of the religion of pagan Ireland is one of animism dominated by superstition – belief in omens and soothsaying, in the power of the curse, in the efficacy of magic formulae and the power of sacred places.

To suggest that the lack of a strongly organised religion among the Irish, and their susceptibility to superstition, made it relatively easy to convert them to Christianity does not necessarily disparage the achievement of Patricius and his helpers and successors. It seems quite likely that the Irish were more innately disposed to accept the doctrines and practices of Christianity than were other cultures. Whatever the reason, it cannot be denied that the people of Ireland gave Christianity an unusually enthusiastic reception. There is not a single martyrdom recorded in the whole history of the conversion of the island, although Patricius tells us that he lived in daily expectation of ‘murder, fraud or captivity’. Neither is there any record of violence erupting between the Christians and those who preferred to stay pagan.

Kenneth Neil, the historian, has drawn some interesting conclusions about the relationship between the native religion and the mission of Patricius:

No matter how great the force of Patrick’s personality, other factors must have played a part in the amazingly rapid conversion of the Irish. The fact that the indigenous religion was pantheistic and not tied to strict doctrine helped immeasurably; from the beginning the Celts seem to have been willing to accept Christ as just another divinity, thereby giving early missionaries a valuable foothold. Natural events also worked in their favour. A great plague struck Ireland during the 540s, killing up to half the population and probably convincing many of the survivors that the new religion offered their only hope for the future.

It is remarkable that those missionaries who followed Patricius showed none of the hostility to native lore and tradition which is customary in the proselytising Christian. Patricius himself seems less tolerant of pagan practices than do some of his successors. By the ninth century monks were composing poems in the vernacular and commissioning church ornaments in the ‘pagan’ (LaTène)style.

Patricius could have added immeasurably to our knowledge of pre-Christian Ireland, had that been his intention. His Confession is the only piece of writing from fifth-century Ireland to have survived. It is one of history’s great ironies that a document preserved with such care down the centuries takes for granted exactly the knowledge that we are seeking, and proceeds instead to expound on the spiritual experiences of its author:

But after I came to Ireland – every day I had to tend sheep, and many times a day I prayed – the love of God and His fear came to me more and more, and my faith was strengthened. And my spirit was moved so that in a single day I would say as many as a hundred prayers, and almost as many in the night, and this even when I was staying in the woods and on the mountain; and I used to get up for prayer before daylight, through snow, through frost, through rain, and I felt no harm, and there was no sloth in me – as I now see, because the spirit within me was then fervent.

And there one night I heard in my sleep a voice saying to me: ‘It is well that you fast, soon you will go to your own country.’ And again, after a short while, I heard a voice saying to me: ‘See, your ship is ready.’ And it was not near, but at a distance of perhaps two hundred miles, and I had never been there, nor did I know a living soul there; and then I took to flight, and I left the man with whom I had stayed for six years. And I went in the strength of God who directed my way to my good, and I feared nothing until I came to that ship.

Six years tending sheep on a mountain was enough to turn the carefree Romano-British youth into a deeply religious 22-year-old, who already has the steadfast faith in his God which characterises the elder Patricius. On a word from God he finds the courage to travel 200 miles from the place of his captivity to the place where he found the promised ship.

Patricius tells us that when he arrived at the ship he told the captain that he could pay for his journey, but the captain refused to take him on board. But as Patricius was walking away from the ship, praying desperately, one of the men shouted to him to come back, and he was taken aboard.

The man said to Patricius: ‘Come, hurry, we shall take you on in good faith; make friends with us in whatever way you like.’ And Patricius continues: ‘And so on that day I refused to suck their breasts for fear of God, but rather hoped they would come to the faith of Jesus Christ because they were pagans.’ Does the phrase ‘on that day’ imply that Patricius had previously indulged in the native rite of the sucking of breasts to symbolise the giving and receiving of protection, but desisted on this occasion because his journey had been dictated by the Lord? Whether it does or not, the casual comment certainly shows how alien Irish society of the time was to anything Patricius would have known in Roman Britain.

Patricius takes up the story again:

… we set sail at once. And after three days we reached land, and for twenty-eight days we travelled through deserted country. And they lacked food, and hunger overcame them; and the next day the captain said to me: ‘Tell me, Christian: you say that your God is great and all-powerful; why, then, do you not pray for us? As you can see, we are suffering from hunger; it is unlikely indeed that we shall ever see a human being again.’

I said to them full of confidence: ‘Be truly converted with all your heart to the Lord my God, because nothing is impossible for Him, that this day He may send you food on your way until you be satisfied; for He has abundance everywhere.’ And, with the help of God, so it came to pass: suddenly a herd of pigs appeared on the road before our eyes, and they killed many of them; and there they stopped for two nights and fully recovered their strength, and their hounds received their fill, for many of them had grown weak and were half-dead along the way. And from that day they had plenty of food. They also found wild honey, and offered some of it to me.

It has often been pointed out that it is typical of Patricius’s way of telling a story that he does not mention the hounds at the beginning of the ship episode, but only incidentally, and in the middle of the story. Irish wolfhounds, massive creatures, were greatly prized on the Continent in the fifth century, and this colourful detail of the Confession – that the ship bearing Patricius out of imprisonment was carrying a cargo of wolfhounds – is historically plausible. Symmachus, writing shortly before this time, says that Irish hounds were brought as far as Rome to be exhibited in public games. The hounds were a generally accepted part of the story until as recently as 1968, when the Anglo-Irish scholar and bishop R. P. C. Hanson pointed out that canes in the above passage, which is the one and only mention of dogs in the Confession,could be a corruption of carnes, ‘flesh’, a reading which appears in some of the manuscripts. This reading suggests that the flesh (carnes)of the pigs filled the men’s bellies, and there were never any hounds at all.

Early translations of the Confession refer to the country where Patricius landed as a ‘desert’ – ‘per disertum iter fecimus’ (‘we made a journey through a desert’). But there were no deserts within three days’ sailing of Ireland big enough to travel around in: only sandy patches of coastline. A more likely translation is ‘uninhabited (deserted) lands’. It is just about feasible, given the right winds and tides, that a large currach of the sort in which Patricius would be travelling could reach the coast of Gaul in three days, but the coast of Britain is a far more likely landing place. Patricius, of course, does not tell us where he landed.

Instead he next tells us of a dream he had on the night of the day that they found food. That he chose to include it in this relatively short Confession, written so many years after the event, indicates that it had a great significance for him. Satan, he tells us, tempted him strongly while he was asleep and he felt as if a huge rock had fallen on him and deprived his limbs of all power. He knows not why, but he cried out ‘Helias!’, and while he cried out the sun arose and its rays removed all the weight from him: ‘And I believe that I was sustained by Christ my Lord, and that His spirit was even then crying out in my behalf, and I hope it will be so on the day of my tribulation.’

Patricius himself was puzzled by the word that he chose to call out: ‘But whence came it into my mind, ignorant as I am, to call upon Helias?’ Helias is Latin for Elijah (vocative Helia), and the classical Greek for the sun is Helios. But it is still difficult to see why this dream should have made such a strong impression on Patricius, and many ingenious interpretations have been offered, most of which only serve to complicate the issue. The best explanation seems to be the suggestion that the dream-work in Patricius’s half-conscious imagination was confusing the prophet Elijah, who had a very high status in early Christian times, with the sun god Helios.

The tedious and tortuous debate about Helias is nothing compared to the amount of intellectual ingenuity that has been expended on the next two verses of the Confession:

And once again after many years, I fell into captivity. On that first night I stayed with them, I heard a divine message saying to me: ‘Two months will you be with them.’ And so it came to pass: on the sixtieth night thereafter the Lord delivered me out of their hands.

St Patrick’s Grave, Downpatrick Cathedral, County Down

Although all the authorities agree that St Patrick is not buried beside Downpatrick Cathedral, there is a persistent stream of visitors to his ‘grave’. The large granite slab that marks its supposed location was carved and placed there in 1900 to discourage the practice of removing a handful of earth from the site; so numerous were the pilgrims that there was fear that this custom would erode the hill on which the cathedral stands. © Tourism Ireland.

Also on our way God gave us food and fire and dry weather every day, until, on the tenth day, we met people. As I said above, we travelled twenty-eight days through deserted country, and the night that we met people we had no food left.

The debate that has arisen about the number of days that Patricius and the ship’s crew spent wandering in the ‘desert’ is partly due to the imprecision of his Latin. One school of thought maintains that Patricius and the crew travelled together for twenty-eight days, in the midst of which they were held captive by hostile natives for a period of sixty days, and afterwards were either released or made their escape. The other school of thought insists that the sixty days’ captivity which Patricius recalls here happened to him much later in life, during his Irish mission, and is mentioned at this point because the sensation of relief experienced in his ‘Helias’ dream reminded him of the relief he felt at his deliverance then.

Similar difficulties have been caused by Patricius’s next statement:

And again after a few years I was in Britain with my people, who received me as their son, and sincerely besought me that now at last, having suffered so many hardships, I should not leave them and go elsewhere.