9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

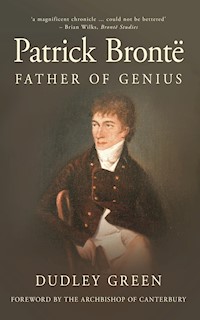

- Herausgeber: Nonsuch Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Patrick Bronte (1777-1861) was the father of the famous Bronte Sisters; Anne, Charlotte and Emily, three of Victorian England's greatest novelists, but he was a fascinating man in his own right and not nearly such an unsympathetic character as Elizabeth Gaskell's Life of Charlotte Bronte would have us believe. Born into poverty in Ireland, he won a scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge, and was ordained into the Church of England. He was perpetual curate of Haworth in Yorkshire for forty-one years, bringing up four children, founding a school and campaigning for a proper water supply. Although often portrayed as a somewhat forbidding figure, he was an opponent of capital punishment and the Poor Law Amendment Act, a supporter of limited Catholic emancipation and a writer of poetry. This is the first serious biography of Patrick Bronte for more than forty years.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

For my sister Rosemary, my brother Stephen, and in memory of my father the Revd Edgar Green, Incumbent of St James’ Church, Ryde, Isle of Wight, 1934–1974, my mother Isobel, and my brother Hugh

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword by the Archbishop of Canterbury

Preface

Acknowledgements and Thanks

Format and Conventions

PART ONE: From Ireland to Haworth, 1777–1820

1. ‘Ireland … Ah! “Dulce Domum”’, 1777–1802

2. ‘I have been educated at Cambridge’, 1802–1806

3. ‘Two Curacies in the South’, 1806–1809

4. ‘I came to Yorkshire’, 1809–1811

5. ‘My dear saucy Pat’, 1811–1815

6. ‘At Thornton … happy with our wives and children’, 1815–1820

7. ‘Providence has called me to labour … at Haworth’, 1819–1820

PART TWO: Faithfulness and Sorrow, 1820–1846

8. ‘The greatest load of sorrows’, 1820–1825

9. ‘Always … at my post’, 1824–1841

10. ‘Intelligent companionship and intense family affection’, 1824–1841

11. ‘I went to Brussells’, 1841–1846

PART THREE: A Varied Ministry

12. ‘Employment … full of real, indescribable pleasure’

13. ‘An advocate for temperate reform’

14. ‘I never was friendly to Church Rates’

15. ‘My aim has been … to preach Christ’

16. ‘Our School has commenced’

17. ‘There is now a great want of pure water’

PART FOUR: Grief and Determination, 1847–1861

18. ‘My Son! My Son!’, 1847–1849

19. ‘I can, yet … take two Services on the Sundays’, 1849–1852

20. ‘His union with my Daughter was a happy one’, 1852–1854

21. ‘My Daughter is indeed dead’, 1854–1855

22. ‘No quailing Mrs Gaskell! No drawing back!’, 1855–1857

23. ‘I wish to live in unnoticed and quiet retirement’, 1857–1861

Epilogue

Patrick Brontë: a Chronology, 1777–1861

APPENDICES

I. The Published Writings of Patrick Brontë

II. Mrs Brontë’s Nurse

III. Three Letters from Patrick Brontë to the Master-General of the Ordnance

IV. The Ecclesiastical Census: Sunday 30 March 1851

V. Servants at the Parsonage

VI. Patrick Brontë’s Curates

VII. Two Letters of Patrick Brontë which have Recently come to Light

VIII. The Article in Sharpe’s London Magazine June 1855

(i) Extract from the article

(ii) Extracts from Mrs Gaskell’s letter to Catherine Winkworth,25 August 1850

(iii) Extract from Charles Dickens’ letter to Frank Smedley, 5 May 1855

IX. Mrs Gaskell’s Portrayal of Patrick Brontë in her Life of Charlotte Brontë

Select Bibliography

Copyright

Foreword by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The Most Revd and Rt Hon. Dr Rowan Williams

Thanks to Mrs Gaskell, the world still has a vivid but pretty misleading picture of Haworth parsonage and its incumbent. This excellent biography, making use of extensive archival material and written by a scholar who has already produced a first-class edition of Patrick Brontë’s correspondence, gives us for the first time a really three-dimensional portrait of a man remarkable in his own right as well as remarkable for being the parent of one of the most gifted families in the history of English literature, a man whose gifts took him from early poverty to acquaintance with some of the leading figures of his generation.

We learn in these pages something that is often forgotten: that the difficulties of travel in the early nineteenth century did not in the least prevent people from enjoying a cosmopolitan experience and perspective. The Brontës were never prisoners in remote Yorkshire, but shared in the intellectual and imaginative currents of the day; they may have been in important senses ‘local’ voices, giving unforgettable shape to a particular landscape. But they were also Europeans, absorbing the challenge of a wider world.

We see also, though, what the conditions of life were in rural Yorkshire at the time, what kinds of poverty and vulnerability to disease were the daily accompaniments of life, not only for the poor but for the professional classes, too. This book shows us not just a remarkable man in the setting of his remarkable family, but an ordinary, devoted parish priest, at the service of a community, struggling with their irregularities, ministering in their needs and taking responsibility for their education, painfully conscious of and angry about the practical help that was denied them in times of economic hardship or epidemic. Here is early nineteenth-century rural society in miniature, neither romanticised nor made impossibly remote from us.

This is a very welcome book indeed, which will illuminate the background of that endlessly fascinating family, but will also tell us all sorts of things we did not know about Church and society in a period of dramatic change, the period of a life spanning the long Hanoverian afternoon, the French wars and the beginnings of the Victorian age. It is a study full of detail, energy and insight, and it is a delight to be able to commend it to the reader.

Rowan Cantuar:

Preface

Patrick Brontë was a clergyman of the Church of England for fifty-five years. His career is remarkable, both for his emergence from a poor and humble background in the north of Ireland to take his degree at St John’s College, Cambridge, and proceed to ordination, and also for his long clerical ministry, forty years of which were spent in Yorkshire as the incumbent of Haworth during a period of great social and ecclesiastical change in the country. As the son and grandson of clergymen my interest in the Brontë family has always centred on Patrick and on the details of his clerical life. When I retired from teaching in 1995, in an effort to discover more about his ministry, I decided to make a collection of his letters. During the next ten years I managed to identify around 250 letters. These showed a wide variety of content. Some were personal, relating to the members of his family and to the sad bereavements which he suffered. Others dealt with the many concerns of a busy incumbent in his parish. A significant number were written to the local press and showed his interest in the wider issues of the day, while others revealed him to be a resolute campaigner on a variety of local matters. My edition of The Letters of Patrick Brontë was published in 2005.

It is unfortunate that, in the century and a half since Mrs Gaskell published her famous Life of Charlotte Brontë in 1857, Patrick Brontë has been a much maligned man. In an effort to clear Charlotte and her sisters of the charges of coarseness and insensitivity in their novels, Mrs Gaskell portrayed them as living in a wild and remote area cut off from the normal decencies of civilised society, and their family background as lonely and austere. She also depicted Patrick as a remote father given to eccentric behaviour and strange fits of passion. The justifiably great success of her biography has meant that her unfavourable portrait of him has remained etched in the public mind ever since. In this, the first biography of Patrick to be published for over forty years, I have made an attempt to redress the balance. It has been my aim to present a fair and accurate account of Patrick’s life and ministry, based on the considerable documentary evidence which is available. I hope that the picture here presented reveals a kindly and loving father who took a keen interest in his children’s development and an able and faithful clergyman, who was ever sensitive to the pastoral needs of his parishioners.

Dudley Green Clitheroe January 2008

Acknowledgements and Thanks

I should like to express my thanks to Dr Rowan Williams for the honour he has done me by writing the Foreword to this work. In the midst of the very busy schedule of a Lambeth Conference year it was an act of kindness which I deeply appreciate. I think his action would have brought great pleasure to Patrick Brontë. For much of Patrick’s time at Haworth his diocesan was Dr Charles Longley, the first Bishop of Ripon, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury and founded the Lambeth Conference. Among the new items in my book is a moving letter from Patrick Brontë thanking Dr Longley for his expression of sympathy at the time of Charlotte’s death. This letter has only recently been discovered among the Longley Papers in Lambeth Palace Library. I am very grateful to the Right Rev’d George Cassidy, Bishop of Southwell & Nottingham, for putting me in touch with Dr Williams, and for the kind assistance given to me by members of the Lambeth Palace staff, especially by Jana Edmunds.

In my edition of The Letters of Patrick Brontë I expressed my gratitude to those who had assisted me in my research during the previous ten years. I should again like to thank Robert and Louise Barnard for their continued support and encouragement and for making available information from their Brontë Encyclopaedia prior to its publication last year. Robert also read my MS in draft form and made many helpful suggestions. A great debt is also due to my brother Stephen who has once again proved to be a mine of information on ecclesiastical matters and, although not an inveterate Brontë lover, read my draft MS through on two occasions and gave much useful advice. I am grateful to Wendy Smith for kindly reading through my proofs. My thanks are due to Ann Dinsdale for her expert help and advice and for the warm welcome which I received on my visits to the library at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. I am also grateful to Sarah Laycock for her work on the illustrations.

Once again I acknowledge my great debt to Juliet Barker’s The Brontës, a monumental work which, with its detailed notes of reference, is an indispensable aid to all those who engage in research on the Brontë family. I have also made frequent use of Margaret Smith’s meticulous three-volume edition of The Letters of Charlotte Bronte and I have gained much information from A Man of Sorrow by John Lock and W.T. Dixon, who had access to some details about the life of Patrick which sadly have since been lost.

I am grateful to my friends in the Irish Section of the Brontë Society for their help over the details of Patrick’s childhood and youth: to Margaret Livingston for arranging my visits to Northern Ireland, to Ivan and Roberta McAulay for kindly providing hospitality and to Finny O’Sullivan for reading my Irish chapter and giving me historical advice. I should like to thank Malcolm Underwood, the Archivist of St John’s College, Cambridge, for his assistance over the details of Patrick’s scholarships at the college. I am grateful to Richard Middleton, the Archivist of the Minster Church of All Saints, Dewsbury, for supplying me with his history of the church, to Robin Greenwood for once again allowing me to profit from his detailed knowledge of the nineteenth-century history of Haworth and to Ruth Battye for her kind hospitality on my visits there. I am indebted to Mr W. R. Mitchell for his permission to use the photograph of Dr William Cartman, his great-great-grandfather and Patrick’s life-long friend. I am grateful to the late Geoffrey Sharps for his assistance over the date of the third edition of Mrs Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë and for sharing with me his knowledge of the background to the article on Charlotte Brontë in Sharpe’s London Magazine. I also wish to thank Brian Wilks for informing me of the recently discovered letter which Patrick wrote to the Bishop of Ripon after Charlotte’s death. I am grateful to Andrew McCarthy for his information on publicity and to Joan Leach, Professor John Chapple and Alan Shelston for their assistance and encouragement.

I should like to record my particular thanks to Simon Hamlet of Nonsuch Publishing for his constant support and encouragement. He has been patient in dealing with my many queries and I am grateful for all his help and advice. I should also like to thank his editorial assistant, Joanna Howe.

Finally, I wish to pay tribute to the memory of three friends in the Brontë Society who have greatly influenced me in my knowledge and understanding of Patrick Brontë’s the life and ministry: Chris Sumner, for many years Chairman of the Membership Committee who inspired all who knew her with her enthusiasm for the study of the Brontës; Muriel Greene, formerly the Secretary of the Irish Section, who was the first to take me round the places associated with Patrick’s early life in County Down; and Charles Lemon, member of Council and editor of Transactions, whose record of seventy years unbroken membership of the Society was an indication of his life-long devotion to the Brontë family.

Format and Conventions

Quotations in the text

The MS spelling and punctuation has been followed in all cases. Obvious misspellings have been left without comment, less obvious ones are marked [sic]. For greater clarity, authorial deletions have been omitted except where they are relevant to the subject-matter.

Rendering of the name Brontë

Although Patrick Brontë almost invariably accentuated the final syllable of his surname, he was not consistent in his method. The first appearance of the diaeresis in his surname was on the title page of The Cottage in the Wood, published in 1815. Since Patrick did not use it at this time in his signatures on letters and in the church registers, it seems that this was a printer’s error. It was not until December 1849 that he began to use the diaeresis in his letters. Prior to that date he usually signed himself Brontē or Bronté. For the sake of consistency, in this work his name is always written Brontë.

Symbols used in quotations from original MSS

I have no objection whatever to your representing me as a Little eccentric, since you and your learned friends would have it so; only don’t set me on in my fury to burning hearthrugs, sawing the backs off chairs, and tearing my wife’s silk gowns … Had I been numbered amongst the calm, concentric men of the world, I should not have been as I now am, and I should in all probability never have had such children as mine have been.

Patrick Brontë to Mrs Gaskell, 30 July 1857

I have not the honour of knowing you personally, and yet I have a feeling of profound admiration for you, for in judging the father of a family by his children one cannot be mistaken and in this respect the education and sentiments that we have found in your daughters can only give us a very high idea of your worth and of your character.

Monsieur Heger to Patrick Brontë, 5 November 1842

PART ONE

From Ireland to Haworth, 1777–1820

1

‘Ireland … Ah! “Dulce Domum”’ 1777–1802

I had a letter lately from Ireland, They are all well. Have you heard, since I saw you, from America? And how are your relations there? Ah! “Dulce Domum”.1

Patrick Brontë to the Rev’d John Campbell,212 November 1808

‘My father’s name was Hugh Brontë. He was a native of the south of Ireland.’ So wrote the seventy-eight-year-old Patrick Brontë to the novelist Mrs Gaskell on 20 June 1855, eleven weeks after the death of his daughter, Charlotte. After hearing that Mrs Gaskell was agreeable to his request that she should write an account of his daughter’s ‘life and works’3 and, feeling that it would be necessary to gratify curiosity about Charlotte’s family background, he proceeded to give her some further information about his father and about his own early life in Ireland:

He was left an orphan at an early age. It was said that he was of ancient family. Whether this was or was not so I never gave myself the trouble to inquire, since his lot in life as well as mine depended, under providence, not on family descent but our own exertions. He came to the north of Ireland and made an early but suitable marriage. His pecuniary means were small – but renting a few acres of land, he and my mother by dint of application and industry managed to bring up a family of ten children in a respectable manner. I shew’d an early fondness for books, and continued at school for several years. At the age of sixteen – knowing that my father could afford me no pecuniary aid – I began to think of doing something for myself. I therefore opened a public school – and in this line I continued five or six years. I was then a tutor in a gentleman’s family – From which situation I removed to Cambridge and enter’d St John’s College.4

This statement, tantalisingly brief though it is, represents the only account we have in Patrick’s own words of his Irish origins. It may be regarded as the irreducible minimum of what is known of his boyhood and early life.

The only other account of Patrick’s Irish background to be given in any detail during his lifetime was in an article which appeared in the Belfast Mercury under the heading ‘Currer Bell’a few weeks after Charlotte’s death:

We recently quoted from the Daily News an interesting article on this gifted authoress, or rather on the person known to the reading public by that pseudonym. We have since learnt some particulars respecting her father’s family which will be more especially interesting to our readers, when they learn, probably for the first time, that they were natives of the county Down. The father of the authoress was Mr Patrick Prunty, of the parish of Ahaderg, near Loughbrickland. His parents were of humble origin, but their large family were remarkable for physical strength and personal beauty. The natural quickness and intelligence of Patrick Prunty attracted the attention of the Rev Mr Tighe, rector of Drumgooland parish, who gave him a good education in England and finally procured him a curacy in —. In his new sphere he was not unmindful of the family claims, for he settled £20 per annum on his mother.5

The publication of Mrs Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë in March 1857 focused attention on the lives and background of the Brontë family, and after Patrick’s death in March 1861 this interest continued to grow. In 1893 the Revd Dr William Wright (a native of Finard, near Rathfriland, County Down, and a former Presbyterian missionary with the British and Foreign Bible Society in Damascus) published an exhaustive study of the Brontë family’s Irish background. Based on his interest in the family from his student days at Queen’s College, Belfast, in the 1850s, and also on several visits to Ireland after his return from the Middle East in 1875, it is at once a fascinating but also an exasperating work.6

Many of Dr Wright’s informants were able men of integrity, who had a good knowledge of the Brontë homeland in the 1840s and whose family connections went back to the time of Patrick Brontë’s boyhood. Chief among them was the Presbyterian minister of Finard, the Revd William McAlister, who had been Wright’s classics master in the 1850s. He told Wright that Patrick’s father, Hugh, had a considerable local reputation as a storyteller. He said that as a child he had heard his father’s account of Hugh Brontë’s fireside tales, and he even claimed to have heard the aged Hugh himself. In his tuition of the young Wright, McAlister had shown himself to be an imaginative teacher. He had sometimes given his pupil the plot of a Greek play and left him to fill in the details in his own words, and occasionally he had treated the stories told by Hugh in the same way. This creative method of teaching may be admirable for developing a pupil’s imagination, but it is hardly calculated to produce a desire for scholarly precision. Much of Wright’s account of the Brontë family is couched in this folk-tale style of writing, where the essential feature seems to be the quality of the story rather than the accuracy of the facts.

The uniformly Presbyterian connection of Wright’s informants has given rise in the minds of some critics to the suspicion that it was one of Dr Wright’s aims to stress the influence of Presbyterianism on the Brontë family. It was also his declared intention to emphasise the hitherto-neglected Irish contribution to the Brontë story. We have, therefore, to be on our guard when we see claims for an Irish origin for the plot of Wuthering Heights, and an Irish venue cited for Patrick’s famous encounter with a drunken bully on the Sunday School walk.7 We also have to remember that Wright’s book was published over ninety years after Patrick left Ireland, at a time when myths about the Brontë family were proliferating. The comprehensive nature of Wright’s study, however, makes it the only source available for much of his narrative. There are very few written sources for that time in Ireland and verification of Wright’s account is in most cases not possible. Moreover, it was an age when oral tradition was seriously regarded and any attempt to provide a narrative of Patrick’s early life must take account of Wright’s work, although we have to realise that for much of the time we are not in the field of serious historical writing.

Patrick Brontë was born on 17 March 1777 (St Patrick’s Day), the eldest of the ten children of Hugh and Alice Brontë’. At the time of his birth his parents were living in a small two-roomed cottage at Emdale in the parish of Drumballyroney. While Patrick’s own description of his father’s origins in his letter to Mrs Gaskell was excessively brief, Wright gives an elaborate account of Hugh Brontë’s family background and of the struggles of his early life. Hugh’s grandfather is said to have been a prosperous farmer on the banks of the River Boyne, near Drogheda in the south of Ireland. In the course of his work he made frequent voyages to Liverpool to sell cattle. After one of these journeys, he agreed, on the promptings of his wife, to adopt a strange child who had been found abandoned on the ship after its return to Ireland. The adopted child, who was given the name of Welsh, soon became Mr Brontë’s favourite in the family. Welsh took a great interest in the cattle-dealing business and Mr Brontë came to depend on him. This aroused the jealousy of the rest of the family and, after Mr Brontë’s death, Welsh was thrown out of the house. He later got his revenge. After securing the post of sub-agent of the estate, he deceived and married Mary, one of the Brontë daughters, and, after evicting the family from their holding, he took possession of the farm himself. But he then suffered a change of fortune. A fire destroyed the farmhouse and he fell into poverty. Having no son and heir, he went to visit one of his wife’s brothers, now a prosperous farmer in a distant part of Ireland. After expressing penitence for the wrongs he had brought on the family and a desire to make amends, Welsh persuaded his brother-in-law to agree that he should adopt one of his sons, named Hugh. The young boy, aged seven or eight at the time, was taken on a long and exhausting journey to the old Brontë farm on the banks of the River Boyne. Here he was brought up in appalling conditions. He received cruel treatment from his uncle and was expected to work all day on the farm. Several years passed until eventually, at the age of fifteen, Hugh managed to escape and make his way north.

The links between Wright’s account and the story of Wuthering Heights are obvious. Even some of the details are similar. Welsh had a sanctimonious servant called Gallagher who reported on Hugh’s shortcomings and gloated over his sufferings. It should also be noted that the dog which befriended the young Hugh on Welsh’s farm was called Keeper.8 Wright’s account is said to be based on the story Hugh himself told of his early life, but it must be remembered that it first appeared in print over forty years after the publication of Wuthering Heights. We have to take seriously the possibility that it may reflect a desire to show an Irish origin for the structure of Emily’s plot. None of the participants in this strange story were alive at the time of Wright’s investigations and it is not possible to check the authenticity of his account. Moreover, he tells the story in a highly dramatic manner and in a style which seems more appropriate to a folk-tale. Edward Chitham, who in his examination of Wright’s account shows himself to be the most sympathetic of his critics, is forced to conclude:

We do not find in Wright’s record any intense or close study of a scholarly kind: his method used intuition, charm, lengthy and capacious but perhaps inaccurate memory, and elegant language.9

In his description of the circumstances leading to Hugh Brontë’s marriage, Wright seems to be on slightly firmer ground. After travelling north from the Boyne, Hugh secured work at some lime-kilns at Mount Pleasant, near Dundalk in County Louth. He did so well there that he was promoted to be overseer. His work eventually brought him into contact with Paddy McClory, a red-haired Catholic youth, who regularly came south from Ballynaskeagh in County Down to obtain lime. A friendship developed between the two young men and Hugh was invited to visit the McClory household, where he rapidly fell in love with Paddy’s sister, Alice (who seems also to have been known as Eleanor). As a Catholic family, however, the McClorys strongly opposed any possibility of Alice entering into a marriage with the Protestant Hugh Brontë. Plans were made for her to marry a Catholic farmer who lived nearby, but on the day appointed for the wedding Alice eloped with Hugh. After their marriage in Magherally parish church, near Banbridge, they set up home in a small cottage in Emdale in Drumballyroney parish. Patrick Brontë was born in the following year. Although once again the details of this account cannot be substantiated, there is nothing in the essentials of Wright’s story that runs contrary to Patrick’s own laconic statements about his father. The places mentioned may still be visited today, and Catholic descendants of the McClory family still live in the neighbourhood of Emdale.

The early days of Hugh and Alice’s married life must have been very difficult. The small cottage had two rooms. At the back was their bedroom and the front room served as a kitchen and as a reception room. It also seems to have been used as a primitive sort of kiln, so that Hugh could earn a living by drying his neighbours’ corn. He is later said to have been a ditcher and maker of fences and, according to Patrick, he rented a few acres of land. Hugh must have prospered to some extent, however, for the baptismal record of his third son, also called Hugh, shows that by May 1781 he had moved his family to a more substantial house in nearby Lisnacreevy. By the time of the birth of his last daughter, Alice, the family had moved again to a large house at Ballynaskeagh, just uphill from the McClory cottage where Hugh had first set eyes on his future wife.

Hugh Brontë’s greatest claim to fame in his locality, according to Wright, was as a storyteller in the old Irish tradition, a role similar to that of the Homeric bard. During long winter nights he would sit beside the fire telling stories to an audience of rapt visitors. He only learned to read late in life and his favourite books were the Bible, The Pilgrim’s Progress and the poems of Robert Burns. He also had a reputation as a passionate supporter of the rights of tenant farmers against their unscrupulous landlords. The only first-hand account we have of him was given by Patrick’s sister Alice a few days before her death in 1891 at the age of ninety-five. Speaking to the Revd J. B. Lusk, the Presbyterian minister at Glascar, she said:

My father came originally from Drogheda. He was not very tall, but purty [sic] stout; he was sandy-haired, and my mother fair-haired. He was very fond of his children and worked to the last for them.10

No baptismal records were kept in the parish of Drumballyroney until after 1778, when the Revd Thomas Tighe became the vicar, so there is no record of Patrick’s baptism in the parish register. When, in 1806, at the time of his ordination, Patrick needed to prove his age, he had to ask his father to sign a certificate. The signature ‘Hugh Bronté’ on the document which was then drawn up is the only written record we have of Patrick’s father.11

By his own account the young Patrick showed an early interest in books. We have no knowledge of the school he attended, although the account of his sister Alice’s funeral in the Banbridge Chronicle in January 1891 stated that he ‘was educated at a school near Glascar’. It seems that as a lad he frequented the blacksmith’s forge in Emdale and at some stage received training in weaving. According to Wright’s account the critical moment in his intellectual development occurred when the Revd Andrew Harshaw, a Presbyterian minister who ran a small school at nearby Ballynafern, overheard Patrick reading aloud from Milton’s Paradise Lost. Realising the young man’s intellectual potential, Harshaw agreed to give him free tuition in the early hours of the morning, leaving him free to continue his weaving during the daytime.

Eventually, through Harshaw’s influence, Patrick was appointed schoolmaster of the Glascar Hill Presbyterian church school. Here he showed himself to be an enlightened teacher, carefully matching his pupils’ tasks to their intellectual capabilities. During the summer holidays he also took parties of senior pupils on walking expeditions in the Mourne mountains. In support of his account, Wright cites the evidence of the Revd John McCracken, minister of Ballyeaston Presbyterian church, Belfast. McCracken had been baptised at Glascar in January 1836 and he had often heard his mother tell how, as a very young girl, she had been a pupil at the school in Patrick’s time. Wright also claims that it was at this time that Patrick started writing poetry. He even goes so far as to say that most of the poems published in 1811 in Patrick’s collection of Cottage Poems were written during his time at Glascar.12

Patrick’s appointment as schoolmaster at Glascar Hill came to an abrupt end when he was detected among the corn-stacks kissing one of his older pupils, a red-haired girl called Helen. She was the daughter of a prosperous farmer who was also a senior officer of the Glascar Presbyterian church. The family were outraged and Patrick was dismissed from his post, and it seems that the school was disbanded. After an interval of some months, again through the influence of Andrew Harshaw, Patrick secured the post of teacher at the Drumballyroney parish school and also tutor to the children of the vicar, the Revd Thomas Tighe.

Any assessment of Wright’s description of Patrick’s time at Glascar has to take into account the two tendencies which are inherent throughout Wright’s work. The first is to stress the influence of the Presbyterian Church over the early years of Patrick’s life, seen here in the advice given him by the Revd Andrew Harshaw.13 The second, even more prevalent, is Wright’s frequent claim to have discovered an Irish origin for the flowering of the Brontë genius, here seen in his assertion that much of Patrick’s poetry was written during his time as schoolmaster at Glascar.

In his own brief description of his time as a teacher, Patrick told Mrs Gaskell:

At the age of sixteen … I opened a public school – and in this line I continued for five or six years; I was then a tutor in a gentleman’s family.14

If Wright’s account is authentic, Patrick’s statement must refer to his time at Glascar Hill school, but there are difficulties in accepting this. By an odd quirk of historical fate, Patrick’s statement is supported by a piece of documentary evidence. In a letter to the Belfast Newsletter of 23 February 1937, a local historian, C. Johnston Robb, revealed the existence of an account book belonging to John Lindsay of Bangrove, a large house near Hilltown. In this book there is an intriguing entry:

November 1793 Paid Pat Prunty, one pound, David’s school bill.15

Patrick Brontë was sixteen in 1793 and by his own account this was the year he opened a public school. The schoolboy David Lindsay must have been about fourteen at the time, for he was commissioned in the Royal Downshire Militia in 1796. He later served in the 18th Regiment of Foot and died in the West Indies. David’s father would clearly have been a member of the minor gentry and it is hard to reconcile his paying a considerable sum of money and sending his son some eight miles to be educated by Patrick Brontë with Wright’s account of Patrick teaching the children of farmers and labourers in a village school. Unfortunately, the brevity of Patrick’s reference to his time as a teacher and the absence of any evidence to support Wright’s account mean that the details of Patrick’s first teaching post can not be established with any certainty.16

According to Patrick’s statement to Mrs Gaskell, it was in 1798 or 1799 that he took up his post at Drumballyroney. The year 1798 was a significant one in Irish history. Spurred on by the example of the French Revolution, the movement of the United Irishmen, led by Theobald Wolfe Tone, sought to break Ireland’s connection with England and to establish a republic on similar principles. When the government responded with a policy of repression, open rebellion broke out. In the north, County Down was the main centre of rebellion and the revolt was supported by many Presbyterians. Several thousand men gathered on Windmill Hill, Ballynahinch, and in the battle which took place on 12–13 June they were defeated by government forces. One of those who took part was Patrick’s brother William, aged nineteen at the time. William later told his grandchildren how he fled for his life after the battle, taking refuge in County Armagh before making his way home. Government reprisals were savage and William was lucky to escape with his life. Patrick does not appear to have taken any active part in the rebellion. Although in later life he was always fervent in his opposition to any instance of injustice, he had a constant horror of revolution and was a strong supporter of Ireland’s union with England. Many years later, in a letter written to the Halifax Guardian in July 1843, he referred to ‘the insane but fearful project of the repeal of the Union, in the Emerald Isle’.17 And, in a letter to his brother Hugh in November that year, he wrote:

As I learn from the newspapers, Ireland, is at present, in a very precarious situation, and circumstances there must, I should think – lead to civil war – Which in its consequences, is the worst of all wars … But, whatever … be done, should be in strict accordance with the Laws.18

The exact nature of Patrick’s teaching position at Drumballyroney is hard to define. He himself told Mrs Gaskell that he was ‘a tutor in a gentleman’s family’, but there seems some doubt over whether he was appointed to be a tutor to the vicar’s sons or as a teacher in the parish school. A great-nephew of Thomas Tighe, writing in 1879, recalled hearing one of Tighe’s sons claim that ‘Paddy Prunty had a school in one of my father’s parishes’, and that his father had recognised Patrick’s ability and had taken great pains to teach him, although he denied that Patrick had ever been a tutor to the family.19 The church at Drumballyroney was rebuilt in 1800 and it seems that the school was renovated at the same time. It may be that, while he was himself receiving instruction from Thomas Tighe, Patrick was employed by him to teach the country children in the church school. Whatever the nature of Patrick’s appointment at Drumballyroney, however, the friendship and patronage of Mr Tighe was to change the whole course of his life.

The Revd Thomas Tighe was a Justice of the Peace and a man of considerable ability and influence. The fourth son in a rich Irish family, he had been educated at Harrow and St John’s College, Cambridge. After graduating in 1775, he had been a fellow of Peterhouse for three years before returning to Ireland in 1778 to take up the appointment of vicar of Drumballyroney and rector of Drumgooland. He served in this united parish for forty-three years. Tighe was a committed evangelical and his family had entertained John Wesley at their home at Rosanna in County Wicklow during Wesley’s last visit to Ireland in June 1789. As his vicar, Thomas Tighe must have known the young Patrick well, and it seems that he came to recognise his potential as a future minister of the church.

If Patrick was to offer himself as a candidate for ordination, it would be necessary for him to graduate from one of the three Anglican universities of that time: Oxford, Cambridge or Trinity College, Dublin. For university entrance he would need a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin and it is probable that Thomas Tighe provided the necessary tuition. When he had made sufficient progress to be able to consider university entrance it must have seemed obvious that he should apply to St John’s College, Cambridge. Not only was it Tighe’s own college, but it was where other members of his family had been educated. St John’s was also well known for its close connections with the evangelical movement in the Church of England. Moreover, for a man in Patrick’s straitened financial circumstances, it had the added advantage of possessing the largest funds of any Cambridge college for assisting poor but able men to gain a university education. In 1802, on Thomas Tighe’s recommendation, Patrick Brontë, at the age of twenty-five, was admitted to a place at St John’s. In July that year he took the momentous step of leaving his home in County Down and sailing to England to start a new career at Cambridge.

Notes

1. The Latin may be translated ‘how sweet is one’s home’.

2. The Rev’d John Campbell was the curate of St Peter’s, Glenfield. He came from South Carolina, U.S.A., and had been a contemporary of Patrick at Cambridge.

3. PB to ECG, 16 June 1855.

4. PB to ECG, 20 June 1855.

5. The Belfast Mercury, April 1855, quoted in SHB Letters IV, p. 184.

6. Wright, The Brontës in Ireland. Originally published in 1893, it was reissued by the Brontë Society Irish Section in 2004.

7. For this incident see chapter 4.

8. Keeper was the name of Emily Brontë’s dog.

9. Chitham, The Brontës’ Irish Background (Macmillan, 1986), p. 8.

10. Wright, pp. 157–158.

11. The two certificates signed by his father are in the Guildhall Library, London (10326/137).

12. For Patrick’s writings see chapter 12.

13. Wright even goes so far as to claim that it was David Harshaw who was responsible for Patrick considering a career as an ordained minister in the Church of England. Harshaw apparently pointed out to Patrick that in the Church of England he would be able to seek ordination after a university course of three or four years, instead of the eight required by the Presbyterian Church.

14. PB to ECG, 20 June 1855.

15. Chitham, p. 78.

16. One possible link with this time is an arithmetic book by Voster, printed in Dublin in 1789, which bears the inscription ‘Patrick Prunty’s book bought in the year 1795’. This came into the possession of Dr Wright and is now in the Brontë Parsonage Museum. Although the inscription would date the book to Patrick’s time at Glascar, it has no established Brontë provenance and the authenticity of the signature has been called into question.

17. PB to editor of the Halifax Guardian, 29 July 1843.

18. PB to Hugh Brontë, 20 November 1843.

19. Chitham, p. 90.

2

‘I have been educated at Cambridge’ 1802–1806

‘I have been educated at Cambridge, and taken my degree at that first of Universities.’

Patrick Brontë to Stephen Taylor, 8 July 1819

Patrick arrived in England several weeks before the start of the university term. In a footnote to his letter to Mrs Gaskell of 20 June 1855 he said that he entered St John’s College in July 1802. His early arrival in Cambridge is supported by a letter to William Wilberforce, the anti-slavery campaigner and a Yorkshire M.P., written some eighteen months later by Henry Martyn, a fellow of St John’s. Thanking Wilberforce for his offer to give financial assistance to Patrick, Martyn told him:

He left his native Ireland at the age of 22 [sic] with seven pounds, having been able to lay by no more after superintending a school some years. He reached Cambridge before that was expended, and then received an unexpected supply of £5 from a distant friend. On this he subsisted some weeks before entering St John’s.1

Presumably Patrick occupied this time in reading to prepare himself for his degree course. The identity of the ‘distant’, presumably Irish, friend who sent him £5 is not known.

Patrick was formally admitted to St John’s College on 1 October 1802 at the age of twenty-five. The Admissions Register of the college has the following entry for that date:

1235 Patrick Branty Ireland Sizar Tutors: Wood & Smith2

It seems that in his case the college was content with the minimum of information. The columns for Father’s name and address, Mother’s, Birthplace, Age and School or Schoolmaster are left blank. The mistake over his surname was presumably due to his strong Irish accent. When he took up residence two days later, his surname was again written as ‘Branty’, but this time Patrick took pains to have the entry amended to read: ‘Patrick <Branty> Bronte’.3

Patrick’s status is recorded as that of a sizar. Undergraduates at that time were classified in three groups: fellow commoners, pensioners and sizars. Fellow commoners were noblemen, of whom there were seven entering St John’s that year. They dined separately with the fellows of the college. Pensioners consisted of the younger sons of the aristocracy, and also the sons of gentlemen and the professional classes: thirty-four of them entered the college in 1802. Patrick was one of four sizars. Sizars were undergraduates who received financial assistance from the college in the form of a reduction of expenses and the provision of rooms free of charge. In return, he was expected to do some form of domestic service and to undertake certain duties, one of which was to record the names of those who failed to attend the compulsory university sermon.

Life at St John’s must have presented Patrick with many financial problems, despite the assistance he received from his status as a sizar. On entry to the college he would be required to pay the sizar’s reduced admission fee of £10 and thereafter 6/4d (32p) a quarter. In addition, there were fees to be paid to the university on matriculation and graduation. He would also be responsible for providing wood and coals to heat his rooms and candles for lighting. An interesting commentary on Patrick’s situation is provided by the evidence of Henry Kirke White, later well known as the author of the hymn ‘Oft in danger, oft in woe’. He was admitted as a sizar to St John’s in April 1804. He was the son of a Nottingham butcher and while at Cambridge had many financial problems. In a letter to his mother of 26 October 1805 he expressed his admiration for the way in which Patrick was coping:

I have got the bills of Mr — [Bronte], a Sizar of this college, now before me, and from them and his own account, I will give you a statement of what my college bills will amount to … 12£ or 15£ a-year at the most … The Mr [Bronte] whose bills I have borrowed, has been at college three years. He came over from [Ireland], with 10£ in his pocket, and has no friends or income or emolument whatever, except what he receives from his Sizarship; yet he does support himself, and that, too, very genteelly.

All the sizars dined in hall, where as White explained, the provision of food was generous:

Our dinners and suppers cost us nothing; and if a man chooses to eat milk-breakfasts, and go without tea, he may live absolutely for nothing; for his college emoluments will cover the rest of his expenses. Tea is indeed almost superfluous, since we do not rise from dinner until half-past three, and the supper-bell rings a quarter before nine. Our mode of living is not to be complained of, for the table is covered with all possible variety; and on feast-days, which our fellows take care are pretty frequent, we have wine.4

One wonders what Patrick’s feelings were as he regularly passed through the great Tudor gateway of St John’s. Fifteen years earlier William Wordsworth had entered the college. He was well aware of its distinguished history and looking back on his experience a few years later he wrote in The Prelude:

I could not print Ground where the grass had yielded to the steps of generations of illustrious men, Unmoved.

And yet he did not take advantage of his time at St John’s. It was not a formative period in his life.

From the first crude days of settling time in this untried abode,

I was disturbed at times by a strangeness in the mind,

A feeling that I was not for that hour,

Nor for that place.5

For Patrick Brontë the opposite was true. He knew that his time at Cambridge provided him with an exceptional opportunity for advancement and he was determined to make the most of his chances. He was fortunate in having an outstanding tutor in James Wood. Wood came from Bury in Lancashire and was the son of a weaver. He had entered the college as a sizar in 1778, and in his early days as a student had known great poverty. Unable to afford the cost of lighting, he had studied by the light of the rush candles on the staircase to his rooms, keeping himself warm by wrapping his feet in straw. He was an able mathematician who later became a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Doctor of Divinity. In 1815 he was elected Master of St John’s and in the following year served as Vice-Chancellor of the University. As a sizar who himself had made the most of his opportunities, he clearly gave great encouragement to Patrick, who devoted himself to his studies with resolute determination.

In December 1802 the half-yearly class lists based on college examinations contain twenty-one names in the first class, followed by four other names, the last of which is that of Patrick Brontë, prefaced by the comment: ‘Inferior to the above but entitled to prizes if in the 1st class at the next examination.’6

In June 1803 Patrick’s name was one of nineteen listed in the first class and he maintained this position for the rest of his time at Cambridge. He was one of only five in his year to achieve this distinction. Those placed in the first class in both annual examinations were entitled to prizes. Two of the books which were awarded to Patrick are now in the Brontë Parsonage Museum.7 One is a copy of The Works of Horace edited by Richard Bentley, 1728, with Patrick’s fly leaf entry: ‘Prize obtained by the Rev. Patrick Bronte, St John’s College.’ The other, Homer’s Iliad edited by Samuel Clark, 1729, bears the proud inscription:

My prize book for having always kept in the first class, at St John’s College – Cambridge – P Bronte, A.B. To be retained semper-7

There were several awards available at St John’s for able scholars of limited means. At Christmas 1802 Patrick’s hard work and dedication was rewarded by his election to a Robson Exhibition. William Robson was a citizen of London who had left a benefaction to be awarded to two sizars, who were to be chosen in their first year and to retain their exhibition until they took their degree. Under this award Patrick received a half-yearly payment at midsummer and in December of £2-10-0 (£2.50), a valuable source of additional income. In February 1803 he was also awarded a Hare Exhibition, which he continued to hold until March 1806. This award, endowed by Sir Ralph Hare, was valued at £64 a year, the income of the rectory of Cherry Marham in Norfolk. It was intended for ‘the maintenance of 30 of the poorest and best disposed scholars of the foundation’ and was worth about £2 to each exhibitioner. At Christmas 1803 Patrick was also elected to a Suffolk Exhibition. This was a benefaction endowed by the Dowager Duchess of Suffolk for the assistance of four poor scholars. It gave Patrick a half-yearly payment of 16/8 (about 83p), which he continued to receive for the rest of his time at Cambridge. In midsummer 1805 he was also elected for one half-year to a Goodman Exhibition, which provided him with 14/-(70p). The Goodman Exhibition arose from a benefaction of lands and money endowed in 1579 for the benefit of two scholars by a former Dean of Westminster. These awards gave Patrick an income of between £6 and £7 a year for most of his time at Cambridge.8 He also seems to have earned a little money by tutoring other students. Amongst his books at the Brontë Parsonage Museum there is a copy of Lempriere’s Bibliotheca Classica which bears the inscription: ‘The gift of Mr Toulmen pupil – Cambridge. Price 12s/. [60p].’9

Despite all his efforts at stringent economy, however, Patrick found it very difficult to make ends meet. It seems that he had already taken the decision to be ordained and early in 1804 he approached Henry Martyn, a fellow of the college and a leading evangelical, and asked him whether he knew of any sources of financial assistance for those intending to enter the ordained ministry. Martyn wrote to an evangelical friend of his, the Revd John Sargent, the vicar of Graffham in Sussex:

An Irishman, of the name of Bronte entered St John’s a year & a half ago as a sizar. During this time he has received no assistance from his friends who are incapable of affording him any – Yet he has been able to get on pretty well by help of Exhibitions &c which are given to our sizars. Now however, he finds himself reduced to great straits & applied to me just before I left Cambridge to know if assistance could be procured for him from any of those societies, whose object is to maintain pious young men designed for the ministry.10

On receipt of this letter Sargent contacted Henry Thornton, M.P., a banker and a member of the famous evangelical group known as the Clapham Sect. Thornton was the treasurer of the recently founded Church Missionary Society and also a cousin of William Wilberforce, another member of the Clapham Sect and a former student at St John’s. Wilberforce and Thornton agreed to supplement Patrick’s income for the rest of his time at Cambridge. On 14 February 1804 Martyn wrote to Wilberforce thanking him for his offer of assistance:

I availed myself as soon as possible of your generous offer to Mr Bronte and left it without hesitation to himself to fix the limits … There is reason to hope that he will be an instrument of good to the church, as a desire for usefulness in the ministry seems to have influenced him hitherto in no small degree. I desire to unite with him in thanks to yourself and the directors of the Society.11

This letter is endorsed in Wilberforce’s hand: ‘Marytn abt Mr Bronte Henry & I to allow him 10L each anny’. It says much for Patrick Brontë’s commitment and dedication that men of the calibre of Henry Martyn, Henry Thornton and William Wilberforce were prepared to support him financially during his time at St John’s.

Cambridge was a stronghold of the growing evangelical movement in the Church of England. One of its foremost leaders was Charles Simeon, a fellow of King’s College and the incumbent of Holy Trinity church, Cambridge. He had been one of the founders of the Church Missionary Society in 1799 and he was also a prominent supporter of the British and Foreign Bible Society. He exercised a strong influence in the university and there were regular gatherings of students in his rooms. One of his aims was to recruit dedicated young men for service in the mission field. During his brilliant academic career at St John’s, Henry Martyn had come under Simeon’s influence and, after his ordination in 1803, he served as Simeon’s curate at Holy Trinity church before going to India in 1805 as a chaplain to the East India Company.

Patrick seems to have attached himself to this evangelical circle and may have attended the student gatherings in Simeon’s rooms. When over forty years later his daughter Charlotte wrote to her friend Ellen Nussey thanking her for her offer of a recently published life of Simeon, she told her:

Your offer of Simeon’s ‘Life’ is a very kind one, and I thank you for it. I dare say papa would like to see the work very much, as he knew Mr Simeon.

Three months later she wrote again:

Papa has been very much interested in reading the book. There is frequent mention made in it of persons and places formerly well known to him; he thanks you for lending it.12

Apart from his academic work very little is known of the way in which Patrick spent his time at Cambridge. A close friend was a fellow sizar, John Nunn. They entered the college in the same year and may have shared rooms. We know few details of their friendship at Cambridge but years later Nunn’s niece, while staying at her uncle’s rectory at Thorndon in Suffolk, heard him say of Patrick: ‘He was once my greatest friend.’13

Patrick’s first years at Cambridge coincided with renewed fears of a French invasion of England. Napoleon’s Grand Army was drawn up across the Channel waiting for France to gain control of the sea. Volunteers were recruited for the local militia and by December 1803 over 460,000 men had enrolled. At Cambridge a separate university volunteer corps was formed, which by February 1804 had 154 members, and the university authorities reluctantly gave permission for all lay members of the university to be allowed one hour a day for military drill. The students paraded in the market place and were instructed in the use of arms by Captain Bircham of the 30th Regiment. The St John’s contingent, which was led by the eighteen-year old John Henry Temple, later better known as Lord Palmerston, numbered thirty-five and included Patrick Brontë and John Nunn in its ranks. For the rest of his life Patrick remained proud of his military association at Cambridge with Lord Palmerston, who was destined for an outstanding political career in the highest offices of state. In her Life of Charlotte Brontë Mrs Gaskell noted:

I have heard him allude, in late years, to Lord Palmerston as one who had often been associated with him in the mimic military duties which they had to perform.14

Towards the end of 1805 Patrick took the decision to proceed to his degree after the minimum residence qualification of four years. Since he was unable to submit the required baptism certificate, he secured a statement from his old mentor, Thomas Tighe, certifying his age:

I hereby certify that by the Registers of this Parish it appears that William Bronte, Son of Hugh and Elinor Bronte, was baptized on 16th March 1779 – & I further certify that Patrick Bronte, now of St John’s College, Cambridge, is the elder brother of the said William – & that no Register was kept of Baptisms in this Parish from time immemorial till after Sept 1778 – when I became minister. –

30 Decr 1805

T. Tighe

Minister of Drumballeyroney15

Patrick also obtained a certificate from Dr Fawcett, the Norrington Professor of Divinity, stating that he had attended forty-seven of his lectures. He had missed only three, ‘one omission was occasioned by indisposition, two by necessary business in the country’.16 Patrick graduated Bachelor of Arts on 23 April 1806 at the age of twenty-nine. It was the custom of St John’s to give £4 to all students on obtaining their degree. Patrick must have thought the occasion worthy of a special celebration for he bought a copy of Walter Scott’s Lay of the Last Minstrel which had been published that year. On the flyleaf he proudly wrote: ‘P Bronte. B.A. St John’s College.’17 Oddly enough, Patrick left his name on the college books for two years after taking his degree, despite the fact that this would make him liable for various fees and college bills. It seems that for a time he entertained the faint hope that he might become a fellow of the college.

Patrick now turned his attention to preparations for his ordination as deacon. His friends in the evangelical world clearly gave him support. By 28 June he had secured the nomination of the Revd Dr Joseph Jowett, Regius Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge and vicar of Wethersfield in Essex, to be his curate at a salary of £60 a year.18 Joseph Jowett, who was a fellow of Trinity Hall, the patron of the living of Wethersfield, was a friend of Charles Simeon and a leading evangelical. His sermons at St Edward’s church, Cambridge, drew large congregations and his appointment of Patrick Brontë as his curate was a sign of Patrick’s good standing in evangelical circles.

On 29 June the curate of All Saints’ church, Cambridge, publicly gave notice: ‘that Mr Patrick Bronte intended to offer himself a Candidate for Holy Orders’.19 Three days later the Master and senior fellows of St John’s College signed Letters Testimonial to the fact that:

the said Patrick Bronte hath behaved himself studiously & regularly during the time of his residence amongst us. … Nor do we know that he hath believed or maintained any opinion contrary to the doctrine or discipline of the Church of England.20

Patrick sent these documents to the Secretary of the Bishop of London on 4 July, together with an accompanying letter:

I beg leave to offer myself a candidate for Holy Orders, at his Lordship’s next Ordination. If I be admitted by his Lordship, be so kind as to let me know as soon as convenient, when and where his Lordship will hold his Ordination; and (if customary) what books I shall be examined in; with whatever directions you may judge necessary.21

He was ordained deacon on 10 August by the bishop, Dr Beilby Porteous, in his chapel at Fulham Palace.

Since Dr Jowett would reside in the parish and perform all the duties during the long vacation, Patrick was not required to take up his curacy in Wethersfield until the beginning of October. It seems that he used this time to pay his first visit back to Ireland. In her old age Alice Brontë, Patrick’s youngest sister, told the Revd J. B. Lusk that Patrick returned to Ireland shortly after his ordination and preached at Drumballyroney church: