9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

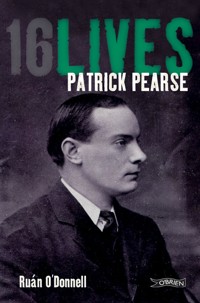

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

On 24 April 1916, as President of the Provisional Government, Patrick Pearse appeared under the GPO Grand Portico on Dublin's O'Connell Street and read aloud the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Nine days later, he was the first of the rebel leaders to be executed. Pearse was born in Dublin on 11 November 1879, to an English father and an Irish mother. Considered the face of the 1916 Easter Rising, for many he was also its heart. In this definitive biography, using a wealth of primary sources, Dr Ruán O'Donnell establishes as never before the significance of Pearse's activism all across Ireland, as well as his dual roles as Director of Military Operations for the Irish Volunteers and member of the clandestine Military Council of the IRB. On 3 May 1916, Pearse was executed in the Stonebreakers Yard at Kilmainham Gaol, at the age of thirty-six.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

JAMES CONNOLLY Lorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALY Helen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTON John Gibney

ROGER CASEMENT Angus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADA Brian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKE Helen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNT Mary Gallagher

THOMAS MACDONAGH Shane Kenna

WILLIE PEARSE Róisín Ní Ghairbhí

CON COLBERT John O’Callaghan

JOHN MACBRIDE Donal Fallon

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN Conor Kostick

THOMAS KENT Meda Ryan

PATRICK PEARSE Ruán O’Donnell

LORCAN COLLINS – SERIES EDITOR

Lorcan Collins was born and raised in Dublin. A lifelong interest in Irish history led to the foundation of his hugely popular 1916 Rebellion Walking Tour in 1996. He co-authored The Easter Rising – A Guide to Dublin in 1916 (O’Brien Press, 2000) with Conor Kostick. His biography of James Connolly was published in the 16 Lives series in 2012, and his most recent book is 1916: The Rising Handbook. He is a regular contributor to radio, television and historical journals. 16 Lives is Lorcan’s concept, and he is co-editor of the series.

DR RUÁN O’DONNELL – SERIES EDITOR AND AUTHOR OF 16LIVES: PATRICK PEARSE

Dr Ruán O’Donnell is a senior lecturer at the University of Limerick. A graduate of UCD and the Australian National University, O’Donnell has published extensively on Irish Republicanism. His titles include Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803; The Impact of the 1916 Rising (editor); Special Category: The IRA in English Prisons, 1968–1978 and 1978–1985; and The O’Brien Pocket History of the Irish Famine. He is a director of the Irish Manuscripts Commission and a frequent contributor to the national and international media on the subject of Irish revolutionary history.

DEDICATION

In memory of Al O’Donnell (1943–2015)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the encouragement of Criostóir de Baróid, Mary Elizebeth Bartholomew, Ken Bergin, Rory and Patsy Buckley, Lorcan Collins, Tony Coughlan, Finbar Cullen, Jim Cullen, Dan Dennehy, Eamon Dillon, Eoin Dougan, Rita Edwards, Seamus Fitzpatrick, Jeff Leddin, Marcas and Leonora McCoinnaigh, Sean McKillen, Ger Maher, Patrick Miller, Dermot Moore, Mary Holt Moore, Brian Murphy, Róisín Ní Ghairbhí, Michael O’Brien, Dick O’Carroll, Labhras O Donnaile, Deasun O Loingain, Seamus O’Mathuna, Owen Rodgers, Charlene Vizzacherro, and Mary Webb (RIP). Thanks also to Maeve, Ruairi, Fiachra, Cormac and Saoirse O’Donnell.

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, 17 March. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, 1 November. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, 31 July. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September. Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07. Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland), a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, 31 August. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, 23 November. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, 25 November. The Irish Volunteers are founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, 20 March. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British Army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, 2 April. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, 24 April. A shipment of 25,000 rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, 26 July. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, 4 August. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, 9 September. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eoin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, 1 August. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, 19–22 January. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, 20 April, 4.15 p.m. The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, 21 April, 2.15 a.m. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand in Kerry. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30 p.m. The Aud is captured by the British Navy and forced to sail towards Cork harbour.

1916, 22 April, 9.30 a.m. The Aud is scuttled by its captain off Daunt Rock.

10 p.m. Eoin MacNeill as Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, 23 April, 9 a.m., Easter Sunday. The Military Council of the IRB meets to discuss the situation, since MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, 24 April, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment, and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: The Young Pearse

Chapter 2: Republican Politics

Chapter 3: Prelude to Insurrection

Chapter 4: Momentum

Chapter 5: Countdown to the Rising

Chapter 6: President and Commander-in-Chief

Chapter 7: Court Martial and Execution

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Chapter 1

The Young Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse was born on 11 November 1879 into a family of English, probably Anglo-Norman, stock and pre-modern Gaelic Irish heritage. His father James was born in London in 1839 and lived for many years in Birmingham where he worked as a stone-carver. The boom in church-building and Gothic decoration brought James Pearse to Dublin, and, by the early 1860s, he was a foreman for Charles Harrison at 178 Great Brunswick Street. From 1864, he sculpted for Earley & Powells of 1 Camden Street.

He had married Emily Fox in Birmingham the previous year. Mary Emily was born in 1864 and James Vincent in 1866. Agnes Maud followed in 1869. Both Agnes and her sister Catherine, who was born in 1871, died in early childhood. Such tragedies contributed to an inharmonious marriage, which ended with the death in 1876 of Emily from a spinal infection. She was just thirty years of age.1

A short time later, on 24 October 1877, James married Margaret Brady in the Church of St Agatha, North William Street, Dublin, and they set up home at 27 Great Brunswick Street, modern-day Pearse Street. James operated his stone-cutting business from this address. Great Brunswick Street was a major thoroughfare leading to College Green and fashionable Grafton Street, with easy access to O’Connell Bridge and the north side of the river Liffey. They faced the substantial campus of Trinity College Dublin and were adjacent to Tara Street Fire Brigade Station.

James’s second family produced daughter Margaret (‘Maggie’) in 1878, Patrick in 1879, William in 1881 and Mary Brigid in 1884. Living conditions were far from salubrious but were vastly superior to the city’s notorious tenements where tuberculosis (TB) wreaked havoc.

Margaret Brady’s extended clan had farming interests, which provided the city-born Pearse children with a modicum of rural exposure. Contact with their great-aunt Margaret was especially significant. In 1913, Pearse wrote:

I had heard in childhood of the Fenians from one who, although a woman, had shared their hopes and disappointment. The names of Stephens and O’Donovan Rossa were familiar to me, and they seemed to me the most gallant of all names; names which should be put into songs and sung proudly to tramping music. Indeed my mother (although she was not old enough to remember the Fenians) used to sing of them in words learned, I daresay, from that other who had known them; one of her songs had the lines ‘Because he was O’Donovan Rossa, and a son of Grainne Mhaol.’2

Pearse’s maternal grandfather, Patrick, had left the Nobber district of Co. Meath in the 1840s to escape the worst years of the Great Irish Famine and had settled in Dublin city. A supporter of the radical Young Ireland movement in 1848, he was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB, aka ‘Fenians’), who, from 1858, revived the revolutionary agenda.3

Pearse recalled a visiting ballad singer performing ‘Bold Robert Emmet’ and other favourites in the republican repertoire, songs that moved him to explore the locality after dark, hoping to find ‘armed men wheeling and marching’. Upon finding none, he sadly declared to his grandfather that ‘the Fenians are all dead’.

Certainly, the family into which Patrick Pearse was born was steeped in Irish cultural inheritance, a tradition of political engagement and a sense of the diaspora.4 At least two Bradys had fought as United Irishmen during the 1798 Rebellion, one of whom was reputedly interred in the ‘Croppies Grave’ on the Tara Hill battle site. Walter Brady, Pearse’s great-grandfather, survived the bloody summer and qualified for the Amnesty Act that enabled the vast bulk of combatants to resume private life. Pearse’s maternal granduncle, James Savage, was a veteran of the American Civil War of 1860–5 in which approximately 200,000 Irish-born soldiers participated. It is unknown whether Savage was one of the tens of thousands who simultaneously joined the Fenian Brotherhood, sister organisation of the IRB, who were reorganised as Clan na Gael. When facing execution in 1916, Pearse claimed, ‘when I was a child of ten I went down on my bare knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I would devote my life to an effort to free my country. I have kept that promise.’5

James Pearse thrived as an independent ecclesiastical sculptor and occasional partner of Edmund Sharp in the late 1870s and 1880s. The firm produced altars, pulpits, railings and expensive features for churches the length and breadth of the country. A healthy volume of contracts brought prosperity, and in 1884 the family relocated to a house at 3 Newbridge Avenue in the coastal suburb of Sandymount.6

Not only a respected craftsman and an independent thinker, James Pearse was also a man versed in English literature. His library included books on the plight of Native Americans, history, legal tracts, language primers and modern classics. Significantly, he possessed republican tendencies and admired Charles Bradlaugh, a radical polemicist with the Freethought Publishing Company. In 1886, James published a pro-Home Rule pamphlet in which he stressed his English ancestry to underline the innate justice of the proposed devolution of local government to Dublin. Raised in a household where aesthetic, philosophical and cultural values were prized, Pearse cherished his ‘freedom-loving’ parents from ‘two traditions’ who ‘worked in me and fused together by a certain fire proper to myself … made me the strange thing I am’.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!