13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

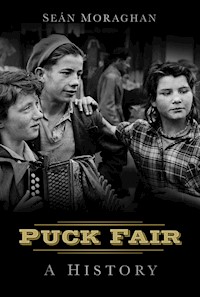

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Puck Fair, Ireland's oldest festival, was established by a royal patent in October 1613, granted to the Welsh planter, Jenkyn Conway, of Killorglin. It first became a famous, however, as a result of the parading and display of a male goat, which is awarded a crown and named as the King of the Town. 2013 saw the celebration of Puck Fair's 400 year anniversary, which was promoted and celebrated as part of The Gathering. This book was launched in August of that year, as part of these festivities.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

1.

The Origins of Puck Fair

2.

Puck Fair during the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries

3.

Puck Fair and the National Questions

4.

Puck Fair after Irish Independence

5.

Puck Fair in the Tourist Age

6.

Puck Fair in Modern Times

Appendix I

Early Origin Stories about the Puck Ceremony

Appendix II

Later Origin Stories about the Puck Ceremony

Appendix III

Report of the Fair from the Cork Examiner, 1846

Select Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks are due to Tommy O’Connor, county librarian, and the staff of the Local History Section at Kerry County Library, Tralee; to the librarian and staff of the Central Library, Grand Parade, Cork; to the librarian and staff of Trinity College Library, Dublin, particularly Martin Whelan who provided a lot of material remotely which otherwise would have been difficult to access; to the Librarian and staff of the National Library of Ireland, Dublin; to the librarian and staff of the Gilbert Library, Dublin; to the keeper and staff of Marsh’s Library, Dublin; to the director and staff of the Irish Traditional Music Archive, Dublin.

Among the most useful books of local history, which went towards the creation of the present volume, and which I appreciated greatly, were Kieran Foley’s History of Killorglin, Patrick Houlihan’s Cast a Laune Shadow, and Michael Houlihan’s Puck Fair History and Traditions. Past issues of the Kerryman newspaper also formed a wonderful repository of details for Puck Fairs over the years which otherwise would have gone unrecorded.

The following people read and commented helpfully on parts of the draft text: Anne Barrett, Marie Duffy, Cayte Else, Joan Greene, Dr Andrew Kelly, Sinéad Kelly, Kieran McNulty, and Perla Moraghan. Thanks also to Julie Gill, who planted the seed, and to David Grant, who helped me to clarify the picture.

Any errors or omissions remain my own. I remain interested in receiving further historical details to do with the fair, and may be contacted at [email protected].

1

THE ORIGINSOF PUCK FAIR

THE CONWAYS

Killorglin’s August fair owes its establishment to Jenkin Conway junior, of Killorglin Castle. In 1613, Jenkin sought official permission to hold a fair in the town, and under a patent granted by King James I, dated 10 October, he was granted the right ‘to hold a faire in Killorgan on Lammas Day and the day after’.1 Such grants permitted the holder to collect tolls on every animal sold at the event. Lammas was the name for the Anglican Church’s August service, held every 1 August, and fairs held in summer were often granted for that day.

Jenkin’s father, also called Jenkin, had been a Welsh settler who was granted Killorglin Castle and the surrounding lands in 1587. Previously, the estate had been a property of the Norman family the Fitzgeralds, Earls of Desmond, who were the lords of north Kerry. Between 1579 and 1583, Gerald Fitzgerald, members of his extended family, and other allies, engaged in a long and bloody rebellion against the imposition of central government control over their extensive territories. In the aftermath the Desmond lands were seized by the Crown, and, under the scheme of the Munster Plantation, they were then rented to English and Welsh members of the nobility, country gentlemen, merchants and soldiers. All the grantees were expected to plant their new estates with further settlers as tenants.

Conway senior had been a captain in Queen Elizabeth I’s army during the Desmond Rebellion. He may have had a hand in attacking Killorglin Castle, and he seems thereafter to have been given the temporary custody of it, along with a garrison of soldiers. He subsequently requested that the lands and castle be bestowed upon him under the terms of the plantation.

The castle had been damaged during the war, and Conway was instructed to build a new castle as part of his grant, with a large ‘bawn’, or boundary wall.2 He named the new building Castle Conway, by which name it, and the town of Killorglin, sometimes continued to be known – doing so was typical of a fashion by planters for naming Irish castles or towns after themselves.

Conway’s grant was confirmed in 1592, and he was subsequently asked to build houses for eight families. He brought over three of his brothers,3 and these may have formed some of the quota. He married and had Jenkin, along with two daughters.

THE LAMMAS FAIR

It has been suggested that Jenkin senior died in October 1612.4 After taking over, perhaps Jenkin junior felt that a fair needed to be established in Killorglin as a way of developing the estate, and applied for the patent to hold one.

The first fair was held in August 1614. If the fair thrived under the Conways, we have no account of it, nor whether the native Irish participated in it. Afterwards, the fair was retained as a valuable revenue-gathering asset by the later landlords of Killorglin, the Blennerhassetts, who married into the Conway family around 1662.5

The fair itself was held at the top of the hill behind the castle, where the ground levels off into a large triangular space; a shape that was typical of fair fields established during the 1600s in planter communities.6 The shape can still be recognised on maps of Killorglin town, and today it is defined by Market Road, Mill Road, and Upper Bridge Street/Main Street. The line of Market Road was probably first formed by the boundary wall surrounding Castle Conway. Until modern times this field continued to be used for the display of livestock at the fair.

It is not known when Jenkin junior died, but he and his son Edward were buried within the castle grounds, apparently in a family chapel built there.7 Antiquarian Charles Smith saw the tomb and read the inscription upon it sometime during the 1750s. Since then, all trace of this structure has vanished and only part of a single wall of the castle remains. Jenkin junior, the founder of Killorglin’s August fair, still lies somewhere in the grounds behind the buildings of Lower Bridge Street, unremembered, as crowds throng the streets around him every August.

The fair appears to have continued long after its foundation and it certainly took place during the eighteenth century. The Gentleman and Citizen’s Almanack for 1734 listed a fair at ‘Kilorgland’, County Kerry, for 1 August.8 After the calendar change of 1752, when Britain and Ireland adopted the Gregorian calendar, fairs and markets became transferred eleven days or so from their original dates, and the Killorglin fair became listed for 12 August, unless the day fell on a Sunday in which case it was scheduled for the following day.9 The fair is known to have taken place in 1786, when the Dublin Evening Post reported an assembly there of agrarian agitators, known as Rightboys.10 At no time was the fair referred to as ‘Puck Fair’.

THE FOLEYS, NEW BARONSOFTHE FAIR

It is the author’s belief that the introduction of the goat parade and display dates from after 1795, and that it came about after local family, the Foleys, bought the right to hold the fair. The author of a letter which appeared in the Kerry Sentinel in 1898 said that the first fair with the goat that he could remember was in 1819.11 In 1837 the first printed reference to the ritual was made, in Samuel Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary of Ireland; the description of Killorglin referred to ‘Puck Fair, at which unbroken Kerry ponies, goats, &c., are sold, and a male goat is sometimes ornamented and paraded about the fair.’12 A goat display was not remarked upon during the 1700s. Charles Smith did not mention it in his comprehensive study of the county, published in 1756.

Smith toured Kerry in 1751 and in the years beforehand. He visited Killorglin, saw Castle Conway, described the settlement as a village consisting of several houses which looked ‘tolerably well for these parts’, and he pointed to its location as an important route into the Iveragh Peninsula. He noted the salmon fishery of the Laune River.13 Of the fair, or of a goat ceremony, he said nothing. Smith was a tireless researcher; he talked to landlords and common folk alike in his search for information; and both he and the circle of his fellows were particularly attracted to the unusual. Given all of that, it is hard to imagine that he would have not heard about, been told about, or repeated the story of the parade and display of a goat. A fair he may have ignored, but not a goat ceremony.

In the summer of 1758, Englishman Richard Pococke, Anglican Bishop of Ossory, toured the south of Ireland, including Kerry, and visited Killorglin. On 21 August he wrote a letter detailing his most recent journeys, mentioning that he had crossed the Laune by boat to see the town, and that one of the Blennerhassetts lived there; but, like Smith, he made no mention of the fair or of a goat display.14

The custom may have been introduced some time after 1795, when Harman Blennerhassett (1764–1831) decided to sell off his Killorglin mansion and lands. He was a cultured, learned gentleman, who had studied at Trinity College Dublin and had trained as a lawyer. However, in 1793 he had joined the United Irishmen, a secret organisation dedicated to the overthrow of British rule. Even more problematically, he also wished to marry his young niece, Margaret Agnew (b.1779). Both of these factors encouraged him to dispose of his estate and emmigrate to America. He sold his estate to the 1st Baron Ventry, Thomas Mullins (1736–1824), of Burnham, Dingle, to whom the Blennerhassetts were related through marriage. Mullins did not reside at his Killorglin purchase, and the old Blennerhassett house was allowed to gradually fall into disrepair.

Landlords possessed several other property rights, which they could use to gain revenue, sell off, or rent to others for a fee. Harman had possessed not only the mansion and lands but also several other benefits, including the right to hold the August fair. Such subsidiary benefits appear to have been disposed of after he left. In 1797, Thomas Mullins purchased from the Blennerhassetts the right to hold a manorial court, a court for the recovery of debts within Killorglin parish, an old right that had first been granted to Jenkin Conway senior.15 Mullins also appears to have bought the right of collecting some of the tithes – monies due from tenant farmers to the Church of Ireland. His descendant, the 3rd Baron Ventry, leased the right to these monies to two other individuals in 1834.16

The Foleys (originally strong farmers of Anglont, 3km from Killorglin), also benefited from the disposal of Harman’s assets. In 1994, Valerie Bary reported that the Foleys had been at Anglont for nine generations, while the family of ‘O’Fowlue’ was listed in the Killorglin area in a census of Ireland carried out in 1659. ‘Sometime around the last quarter of the eighteenth century, it appears that the Foleys became freeholders – unusual at that time’, Bary wrote.17 She believed that the family had bought out their land from MacCarthy of Dungeel, a Catholic landowner who had avoided the land confiscations that had befallen his peers, but who had fallen into debt and had to sell off his estate. The Foleys built an impressive house at Anglont, a large Georgian building which still stands and remains in the family.

In 1798 they bought the fishing rights to the Carha River from Richard Blennerhassett.18 The Foleys were strongly allied to the Blennerhassetts: Michael James Foley (1783–1867)19 also known as ‘Big Mick’, campaigned successfully for candidate Arthur Blennerhassett (1799–1843) of Ballyseedy, Tralee, in the 1837 general election. At some point, around 1800, they appear to have also purchased from the Blennerhassetts the right to hold the fair. One of the Foley men was then entitled to style himself the Baron of the Fair, with the privilege of levying the tolls at the event: the first of these may have been Michael himself, who was certainly called by the title.20

THE GOAT PARADEAND DISPLAY

In 1837, Lewis’s Topographical Dictionaryof Ireland indicated that the goat was at first simply paraded around Killorglin. From 1841 it was displayed from a height.21 In the years afterwards, the goat was raised upon the battlements of the old Conway/Blennerhasset mansion which was no longer occupied by the landlords, and the last tenant of which, Father James Louney (or Luony), had died in 1844. Reports from the mid-1800s indicate that the goat was ornamented with coloured ribbons and this simple decoration is likely to have taken place from the beginning years of the display.22 By 1870, the castle structure had deteriorated so much that the goat was mounted instead upon a tall wooden platform in the town; this was the precursor of the goat stand used today.

THE GOATAS MASCOT

All of this suggests that the goat may have been a sort of mascot, a figurehead, or a symbol for the fair. An account of the event, by the Cork Examiner in 1846,23 described the goat as being decorated with gingerbread and salmon, both products that were offered for sale at the event,24 reinforcing suspicions that the goat display and decoration were intended as emblems of the fair. The use of an animal as a mascot was not a unique one; the fair at Greencastle, County Down, featured a ram placed on the castle walls, and historian of Irish fairs Patrick Logan heard of a custom of decorating the rams at the fair of Dungarvan, County Waterford.25 More significantly, at Mullinavat, County Kilkenny, a fair used to be held which was also called ‘Puck Fair’: ‘he-goats decorated with ribbons were brought to the fair, the best one amongst them was chosen and set up on a cart, drawn through the fair and set up on high in a field in which the fair was held and the owner of which collected tolls’.26

Alternatively, if it was not a mascot for the fair it may have been a mascot for the Foleys themselves, or rather for their faction. The Foleys, in particular ‘Big Mick’ Foley, were famous faction fighters, leading bands of men into street fights with others.27 A puck goat would seem to be a suitable symbol for such aggressive activity, as goats are traditionally associated with butting and kicking. If the origin of the goat display lay in the tradition of faction fighting, once that practice was successfully suppressed it may no longer have seemed savoury to refer to it, and different explanations for the origin of the goat display may have been offered instead.

It is impossible to assert with absolute confidence what the origin of the goat ceremony was. It may have had a much older source as a folk custom, which was unique to Killorglin, the nature of which remains unknown or unknowable. A wide range of different stories have been advanced over the years to account for the ceremony, some of which are more believable than others, and these are listed in the appendices at the end of this book.

Notes

1 Richard Hayward, In TheKingdom of Kerry (Dundalgan Press, Dundalk, 1946) page 230.

2 Valerie Bary, Houses of Kerry (Ballinakella Press, County Clare, 1994) page 155.

3 Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County of Kerry: A New Reader’s Edition (Bona Books, Killorglin, 2010) page 15.

4 M.J. de C Dodd, ‘The Manor and Fishery of Killorglin, Co Kerry’, Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 21, 1944-45, page 167.

5 Bill Jehan, ‘Blennerhassett Family of Castle Conway, Killorglin and Rossbeigh in Co Kerry’, viewed at www.BlennerhassettFamilyTree.com.

6 Patrick J. O’Connor, Fairs and Markets of Ireland: A Cultural Geography (Oireacht na Mumhan, Newcastle West, 2003) page 31.

7 Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County of Kerry: A New Reader’s Edition (Bona Books, Killorglin, 2010) page 67.

8 Watson, John, The Gentleman and Citizen’s Almanack (Dublin, 1734) page 74.

9 See The Gentleman and Citizen’s Almanack for 1764, 1770.

10 Kieran Foley, History of Killorglin (1988) page 34.

11 Quoted in Michael Houlihan, Puck Fair History and Traditions (Treaty Press, Limerick, 1999) page 89.

12 Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland Vol. II (S. Lewis and Co., London, 1837) page 152.

13 Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County of Kerry: A New Reader’s Edition (Bona Books, Killorglin, 2010) page 67.

14Pádraig Ó’Maidín, ‘Pococke’s Tour of South and Southwest Ireland in 1758’, Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Journal, LXIV, Jan-Jun 1959 pages 35-36.

15 Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland Vol. II (S. Lewis & Co., London, 1837) page 152.

16 Kieran Foley, History of Killorglin (1988) page 37.

17 Valerie Bary, Houses of Kerry (Ballinakella Press, County Clare, 1994) page 6; Census of Ireland,1659 (Stationery office, Dublin, 1939) page 247.

18 ‘The humble Petition of Michael James Foley, Philip James Foley, and John Maurice Foley, of Anglont, in the county of Kerry, on their own behalf, and others interested in the weir and fishery of Carha, in the county of Kerry’, in House of Commons Papers, Parts 1-2 (HMSO, London, 1845) pages 80-81.

19 ‘Ireland. Death of Mr Michael James Foley, of Killorglin’, Dorset Chronicle, 31 January 1867. (Reprinted from the Kerry Evening Post.) ‘On the 10th instant, at Anglont, the residence of his son, died this remarkable patriarch, at the advanced age of 84 years … so well known in this county as “Big Mick’’’.

20 ‘Puck Fair’, Tralee Chronicle, 14 August 1857.

21 ‘Puck Fair’, Kerry Evening Post, 11 August 1841.

22 ‘Puck Fair’, Kerry Evening Post, 11 August 1841; ‘Puck Fair’, Tralee Chronicle, 16 August 1851.

23 ‘Puck Fair’, Cork Examiner, 17 August 1846.

24 Lady Gordon, The Winds of Time (John Murray, London, 1934) page 125; ‘Puck Fair’, Tralee Chronicle, 17 August 1850.

25 Patrick Logan, Fair Day: The Story of Irish Fairs and Markets (Appletree Press, Belfast, 1986) page 20.

26 Máire MacNeill, The Festival of Lughnasa (Oxford University Press, 1962) page 292.

27 Kieran Foley, History of Killorglin (1988) page 41.

2

PUCK FAIRDURINGTHE NINETEENTHANDEARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES

For most of the nineteenth century, Puck Fair was held in what was a small, poor village. Most of Killorglin’s population consisted of partially employed agricultural labourers, followed by pub keepers and shopkeepers, and craftsmen such as blacksmiths and harness makers. In 1837 there were 163 houses, with a population of 893 people.1 Access to the town for patrons and livestock from the far side of the Laune River was via an old bridge, built some time in the second half of the eighteenth century and was described in 1869 as ‘a crazy and patched-up, many-arched structure’.2

The goat stand, c. 1900. (From the Lawrence Collection. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Market Road, packed with people and animals, c. 1900. (From the Lawrence Collection. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

A visitor in 1822 said, ‘For dirt and dreariness, Killorglin may vie with any inhabited place in the universe’.3 The fair provided an opportunity to give the town a makeover: the houses were decorated with evergreens,4 and, as the Killorglin correspondent of the Tralee Chronicle observed in 1863:

For some days previous in our good town, for our great annual ‘Blow-out’ Killorglin threw off its sombre look, and assumed a very pale face, by reason of the application of the seldom-used white-wash brush. Carrying out the old aphorism … ‘Were it not for Christmas and Puck Fair, Killorglin would rot.’5

The town began to develop from the second half of the nineteenth century. The Ventry Arms Hotel was established from 1865.6 It stood at the top of Lower Bridge Street, opposite the entrance to Market Road (the building is now Mulvihill’s Chemist). A branch of the National Bank of Ireland was established in Killorglin by 1874, which assisted the commercial side of the fair.7 The old Laune Bridge was acknowledged to be unsafe and a new bridge was completed in 1885, which is the structure still seen today. Most importantly, the Farranfore to Killorglin railway line was opened by the Great Southern and Western Railway Company in January 1885. It entered the town across a viaduct situated towards the seaward side of the town, and the station lay near the present Fexco building on Iveragh Road. The line was later extended west to Valentia Island in 1893, allowing visitors to travel from the town of Cahersiveen. The railway represented a vital improvement to the town, and to the fair. Regular trains were supplemented by special services, which brought visitors in and transported sold animal stock out. (In 1912, it was reported that between 5,000 and 6,000 people arrived and departed by train during the days of the fair, while in the following year a remarkable 200 wagons of stock were despatched.)8 A second hotel, the Railway Hotel, situated opposite the station, was opened in 1887.

THE DAYSOFTHE FAIR

Although the fair is familiar to modern visitors as a three-day event, for most of the nineteenth century it appears to have consisted of two days, 11 and 12 August – the Freeman’s Journal listed the fair for these two days in 1840.9

It later came to be held over three days, starting on the 10 August. This may have arisen for two reasons. It may have been that, as the fame of the fair spread, farmers from further afield brought animals along the roads from greater and greater distances, and a Gathering Day, as it came to be called, gave them time to make the journey for the following day of sale. The 10 August also happened to be the feast day of St Lawrence, for whom the church of Killorglin may have been named (Cill Lorcain, the Church of Lawrence). A church is known to have existed there from at least since 1215, although its precise location is unclear. The 10 August was the day of the patron saint, or the ‘pattern day’, and it brought people into the town for religious devotions. The two events may have coincided; so much so that Puck Fair was later termed as a fair and a pattern.10

Fair Day was always the 11 August, even though buying and selling also took place, although to a lesser extent, on the other two days. Pigs and horses generally seem to have been disposed of by this day, with cattle being sold on 11 August. Scattering Day, the following day, was more for sightseers, for children and young adults, and one less for business than for entertainment.11 These names for the days do not appear in press reports until the late 1890s.

Occasionally, when the fair day proper fell on a Sunday, the event was extended, beginning a day earlier or, more usually, finishing a day later. Generally, no business was done on the holy day.

THE ORGANISERS

The general organisers of the business aspects of the fair were the Foley family. Michael ‘Big Mick’ Foley was noted as the Baron of the Fair in 1857, the Baron being the officer who benefited from the tolls and who organised men to see that they were collected.12 The family more than likely sponsored the bellman, or town crier, who announced important sales and conveyed information to the public; such an official was observed in this duty in 1912.13 As stated earlier, it is the author’s belief that the Foleys also initiated or encouraged the goat parade and display, and this continued to be done in association with the young men of the town; in 1857, ‘The young blood of Killorglin did not neglect to elevate the “Puck Goat”’, and in 1861, ‘The young blood of Killorglin did not forget the time-honoured picture of elevating high above the crowd, and in the most prominent place in our good town, a formidable he-goat’.14

From 1908 until approximately 1919 the presentation of the goat was organised by the members of the Killorglin branch of the Total Abstinence Society. The temperance society had been formed in Cork in 1838 by Father Theobald Mathew, and was committed to eliminating alcohol consumption in Ireland, chiefly by administering The Pledge, a personal commitment to abstain from alcohol for life, to thousands of Irish people at monster gatherings throughout the country. Alcohol was the refuge of the poor and quite often led to public drunkenness, fights and domestic abuse, as well as inflaming episodes of violent political action against the police or agents of the landlords.

From the early 1900s the goats were supplied for the event by Michael Houlihan (1878–1968) who also erected the wooden platform and hoisted the goat up for display.15

POLICE

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) policed the fair, and would usually draft in other officers from surrounding areas to assist them. There would often be approximately fifty men marshalling crowds that could reach thousands in number.16 A police station was situated at Killorglin since at least the late 1830s.17

At the fair of 1862:

As Mr Christopher Harold, of Lissataggle,18 was standing in the very centre of the fair, at about one o’clock, talking to Mr Jonathan Walpole, of Clydane,19 an athletic young man crept up behind him, and, without the slightest warning, gave him a desperate blow of a heavy iron loaded blackthorn stick on the side of the head. Mr Walpole at once, with great presence of mind, pursued the intended murderer, and laid hold of him, and a policeman coming up promptly he was at once secured and conveyed to the police barracks. The constable got possession of the murderous weapon used on the occasion, which was marked with blood.20

After having been attacked on fair day, Mr Harold was again confronted five days afterwards, when a farm labourer who had worked for him threatened him with a pike.21 It was supposed that Mr Harold’s father had ‘rendered himself obnoxious to the Roman Catholic clergy of his neighbourhood by holding prayer meetings in his house and rearing in the Protestant faith two children, offsprings of a mixed marriage, intrusted to his care by a deceased friend’.22

Along with these random acts of crime, the police had plenty to deal with during the fair, from such common assaults to public drunkenness, faction fighting and Traveller rows.