Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

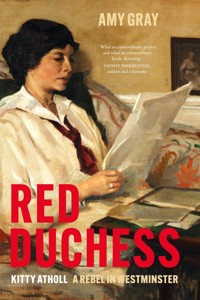

A pioneering female politician who thought women didn't need the vote; a conservative who shared platforms with communists; a shy public speaker who travelled the world speaking for Spanish refugees: the formidable Duchess of Atholl was full of contradictions. Born into an ancient Scottish family and married to a philandering duke, Kitty rose above the constraints of class and convention to become a tireless advocate for women and children. By her election as the first Scottish female MP in 1923, she was one of the most prominent women in Scotland – and that was well before she shocked Westminster with outspoken rebellions against her own government. She stood with Spanish refugees and challenged fascism, visited war zones and campaigned with her political opponents, criticised tyrants and wrote her own political playbook. In Red Duchess Kitty Atholl's extraordinary life is brought to the spotlight she has long deserved – a compelling story of courage, conviction and a woman who refused to play by the rules.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 440

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Amy Gray, 2025

The right of Amy Gray to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 646 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Introduction

1 Thoroughness in All Her Undertakings

2 The One Thought of Her Life

3 A Duchess and a Dame

4 Irrespective of Sex

5 Days of New and Endless Responsibility

6 So Much Bigger and Wider a Life

7 A Sort of Giant Panda

8 Diehards with a Duchess

9 La Duquesa Inglesa

10 Her Views Frighten Me Somewhat

11 Send Hitler Your Answer

12 Every Warning She Has Given Us Came True

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

It is three days before Christmas, 1938. In the Scottish Highlands, it has snowed for weeks and it is bitterly cold. In the dark winter night, a tiny, birdlike 64-year-old woman sits down at her piano, face drawn with exhaustion, heart sick with disappointment. She reaches decades back into her memory for the music embedded in her fingers by thousands of hours of practice, and she turns to the German composers she loves. First she plays Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata, then his Appassionata, and she feels better for it.

She is the Duchess of Atholl, one of the most famous women in the country, and she has just lost the biggest gamble of her political career. Elected Scotland’s first female MP and appointed the first Conservative woman minister, she has become one of the most unlikely rebels in the history of the British Parliament. The prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, has used the full might of his party to crush her. But in just nine months’ time she will be proved right and a war she has tried desperately to avert will change the world forever.

Seventy years after her death, she is far from a household name. The more I learned about her, the more I wondered why not. And when I learned that she had been anti-suffrage before her own election, I was hooked. That, I thought, is an interesting journey.

The duchess trained to be a pianist before a secret engagement led to a marriage scarred by infidelity and money troubles. She was a friend of Winston Churchill who, unlike him, put her views on appeasement to the electorate – and lost. A loyal minister who became a serial rebel against her own party. Ahead of her time on issues like the importance of nursery education and the need to eradicate what was then called female circumcision, but a reactionary on the governance of India and the school leaving age. A shy public speaker who spoke to audiences of thousands, an aristocrat derided for dressing like a governess, ‘Red Duchess’ turned ‘Fascist Beast’. How had all of this existed in the same life?

I turned immediately to the index of every book I picked up and found always Astor, seldom Atholl, always Attlee. In that gap between Britain’s first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons and Britain’s transforming post-war prime minister, the duchess often disappeared. Fragments of her story were told in academic books on the period, but the only biography was long out of print. When I mentioned her to political friends, and on several occasions to extremely senior politicians, I mostly got blank looks. Yet when there were forty male MPs for every female MP, she was one of Parliament’s most frequent speakers. She drew audiences of thousands to her meetings; ‘Anything that the duchess does is news’, reported one newspaper in 1938.1 I set out to understand why her – fascinating, moving, unexpected – story was not better known. How was it that even her own political party had no space to remember Atholl alongside Nancy Astor and Margaret Thatcher?

As I followed her trail through archives in Blair Atholl, Perth, Edinburgh, Cambridge and London, I found her memory cherished by the people who had known her and in the communities where she had lived, but deliberately obscured by many of her own contemporaries. I recognised the woman I found in the women I have known in fifteen years of working in and around politics. Deeply earnest, committed to argument based on facts, crashing constantly up against men who belittle, ignore and dismiss them, putting the concerns of women and children into arenas where they are not otherwise heard. Here, too, were the women I grew up around in military families: unpaid welfare workers following their husbands’ careers, holding the home front together. And here were the squabbles of local political associations I knew all too well, and the perpetual argument about whether MPs are delegates or representatives, which had again become so present during the aftermath of Brexit. Here was a story of pianos, passion – and politics.

Kitty, as I came to think of her, was brave, compassionate and talented, and also stubborn, sometimes blinkered and flawed. She was an inadvertent pioneer, who followed the causes that interested her rather than those that might advance her career. Thirty years before the National Health Service was founded, she endorsed a public health service for the Highlands and Islands; forty years before Margaret Thatcher climbed into a tank turret, Kitty was taking on Communist hecklers from a Cromwell tank.

In other ways she was very much of, or even slightly behind, her time, believing that women’s primary sphere should be motherhood. Devastated by her own inability to have children, she found a maternal role in caring for her husband’s soldiers, and then in bringing 4,000 Spanish refugee children to safety in Britain. After an event at the Scottish Parliament to mark the centenary of her first election, I met the descendants of some of the children she helped, whose families have never forgotten the woman without whom they would have been stranded in a war zone. By retelling her story, I hope to ensure that she is not forgotten again.

1

Thoroughness in All Her Undertakings

1874–1899

‘There is nothing that I love more than Scotland, + life there.’Kitty, August 18971

Kitty Ramsay’s family had lived in the same part of east Perthshire for seven centuries. Her ancestor Neis de Ramsay saved King Alexander II’s life in 1232 with pioneering abdominal surgery to remove a hairball and was granted the estate by the grateful king. Twenty miles north-west of Dundee, Bamff House had started as a medieval tower, before being expanded into a comfortable, if slightly forbidding, home typical of the Scottish gentry. In 1666 the Ramsays were given a baronetcy, and by the late nineteenth century the men of the family were well established as historians, classicists and philosophers. In 1871 Sir James Ramsay became the 10th baronet, following an education at Rugby School and Oxford, before making a half-hearted attempt at a legal career. He settled into life as a gentleman academic and would spend the rest of his life researching and writing a detailed history of England. He was also a keen climber who had made one of the early ascents of Mont Blanc in the French Alps, and enjoyed ‘wooding’ on his 16,000 acres. This love of both serious study and outdoor exercise would shape the interests of all eight of his children. His first wife, Mary, died in 1868, leaving him with three young daughters, Mary (known as Dolly), Lilias (known as Lily) and Agnata.

His second wife, Charlotte Fanning Stewart, was from another ancient Perthshire family, descendants of Robert the Bruce, with a home 50 miles from Bamff on the shores of Loch Earn which had inspired a Walter Scott novel. Charlotte was born in India, where her father was a captain serving with the East India Company at Gwalior. In a single night in 1857, when local soldiers rebelled against British rule, he was seriously wounded, his wife Jane was shot dead and their 2-year-old son Robert was killed in her arms. The next morning, after being told of the death of his wife and child, William was killed. Four-year-old Charlotte only survived by being hidden along with three other children by a family servant. She was brought home by the governor-general’s wife and grew up with family between London and Perthshire. Unsurprisingly, given the events of her childhood, she had frequent nightmares and always had to sleep with a light on in her bedroom, but she grew into ‘a beautiful woman of rare charm, with a [singing] voice of exceptional range and expressiveness’.2 Just 18 when she married Sir James in 1873, ‘Sharlie’ deployed her musical talent to bond with the stepdaughters who were not much younger than her.

Their eldest child, Katharine, known always to her family and friends as Kitty, was born on 6 November 1874, in Edinburgh, seven years after her half-sister Agnata. Queen Victoria had been on the throne for nearly forty years, and would shortly be proclaimed Empress of India by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Britain was the most powerful nation in the world, and Scots were a vital part of its government and the administration of its Empire. Women who were not the empress were not yet equal partners in this Empire, though campaigns for women’s right to vote were beginning to gain momentum. Some women in Scotland were able to stand and vote for school boards, and eighteen had been elected by 1874. Beyond Perthshire, the world was changing fast.

Kitty was followed in the next twelve years by Nigel, Douglas, Ferelith (known as Fairy) and Imogen (known as Baba). The number of children he had to educate and the demands of the estate meant that Sir James had little money to spare, and the children were brought up with few luxuries. In many ways it was a typical Victorian childhood, with physical contact between the sexes carefully restricted, and strict rules about proper behaviour. When he was not prescribing improving reading, Sir James was encouraging lengthy walks and leading ice skating on the pond in the winter. The two brothers, unsurprisingly with six sisters, were close. Fairy and Baba formed another pair as the babies of the family, and Kitty was left isolated, and not always happy, in the middle. She was often ill, ‘handicapped by sore throats, ultimately found to be due to the antiquated drainage system of our old Scots home’.3 The lonely and bedbound young Kitty escaped into books, finding escape and moral instruction in codmedieval romances and tales of the Jacobite rebellions. When combined with the discipline imposed by her father, these formative years shaped a lifelong reserve and shyness. Kitty found it hard to be physically demonstrative, even to her closest family, or to speak about her emotions. It must have been a relief to find one way of expressing herself when she showed a talent for the piano aged 6, starting formal lessons at 11.

Bamff was often let to shooting tenants, so there were regular visits to the extended Stewart and Ramsay families around Perthshire and every summer the children spent two months at St Andrews, 30 miles away on the coast. Kitty’s strongest memories of these holidays were of fiercely contested tennis and golf tournaments with her brothers. While the children’s competitive instincts were developed, their parents were often guests of the Marquess of Breadalbane at Taymouth Castle, where Sharlie’s singing was admired by other guests like the King of Sweden, the Duchess of Montrose and the rising politician George Curzon. Sir James had had a brief flirtation with politics when he stood unsuccessfully for election to Parliament as the Liberal candidate in Forfarshire. He had, however, left the Liberal Party in 1886 when William Gladstone adopted a policy of Home Rule for Ireland, and gradually found his political home as a Unionist (the name the Conservative Party used in Scotland to make its views on Home Rule clear).

Although his thrift and strictness were typical of his peers, unlike most of them Sir James believed strongly in educating girls. His Irish mother and her sisters had been well educated and he took the same approach with his six daughters. Kitty’s older sisters were among the first students to attend St Leonard’s in St Andrews, one of the pioneering schools for girls which aimed to give them an education as good as their brothers received at the traditional public schools. Agnata won a scholarship to Girton College at Cambridge just three years after women students were allowed to enter the university’s examinations. She made national headlines in 1887 when she came top of the final year in Classics, beating all her male contemporaries. It was Kitty who took her the congratulatory telegram from her tutor when the family were on holiday in Brighton – which Agnata made her open and read, too nervous to do so herself.

Kitty first visited London aged 8 so that doctors could assess her sore throat, and when she was a teenager the family moved to The Old House in Wimbledon, which Kitty remembered as having ‘a large drawingroom, admirable for sound, and a nice lawn tennis court’, two crucial things for the musical and sporty Ramsays.4 While Sir James enjoyed the proximity to London’s archives, and Sharlie the busier social life of the capital, Kitty was enrolled as one of the early pupils at Wimbledon High School (founded in 1880). Educated at home until then by Dolly and Lily, between the ages of 13 and 17 Kitty enjoyed the small classes and earnestly dedicated teaching characteristic of these early girls’ schools. She was popular with staff and pupils, and her ‘gaiety and quick sense of humour that went with thoroughness in all her undertakings’ were long remembered.5 Even though she was always the youngest in her form, she was tennis champion, secretary and treasurer to the school library, took part in debating, played Cordelia in a performance of the first act of King Lear, and enjoyed regular trips to museums and the Houses of Parliament. She adored Emma Mundella, the school’s head of music, whose uncle had been an education minister under Gladstone, and who was a gifted teacher and occasional composer. Under Mundella’s careful tuition, Kitty began to master the classical repertoire, playing Schumann and Chopin sonatas at school concerts. Although she had a sweet singing voice, she preferred to shelter behind the keyboard, accompanying the hymns at school prayers. Mundella also began to teach her composition, and Kitty wrote the tune for the school song which is still sung on special occasions today.

Twenty years later, returning as the eminent guest at Speech Day, Kitty would tell the girls that ‘Wimbledon held a very unique place in her heart’.6 She ‘counselled them to get all they could out of their games, friendships, traditions and school societies, and, above all, out of those who taught them’, as she undoubtedly did, making lifelong friends there.7 Combined with the academic atmosphere at home, Kitty’s brain was being well trained to interrogate facts and develop a broad range of interests in a way she would apply throughout her political career. When she was 16, she was offered a scholarship to Somerville Hall at the University of Oxford – but turned it down. She and her brothers had decided that they could not hope to compete academically with Agnata. Kitty chose instead to apply to another young institution, the nine-year-old Royal College of Music, where Mundella had been one of the first to receive a diploma.

In May 1892, aged 17, Kitty entered the Royal College, with piano as her principal study and harmony and composition as her second. Hubert Parry, the celebrated composer now best remembered for his coronation anthem ‘I Was Glad’, was her composition tutor. He was a novel personality for Kitty, with ‘more exuberant vitality than anyone I ever met – he literally exploded with it’, and he and his wife remained good friends of Kitty’s for the rest of his life.8 She worked hard – possibly too hard – and her piano playing improved rapidly; her tutor thought that ‘by a little systematic order she might succeed in getting a large repertory, for she is blessed with an excellent & generally retentive memory’.9 That summer she won one of two college scholarships available to second years. However, when the college principal told her that one of the students she had beaten was going to have to leave without additional financial support, she resigned from the scholarship so that he could have it. She became an honorary scholar, and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the illegitimate son of a Sierra Leonean medical student, was awarded the scholarship. Without it he might not have gone on to become a highly regarded composer, famous for his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast.

Sharlie insisted that Kitty also carry out the social obligations of a baronet’s daughter, and she made her official debut at the Perth Hunt Balls in September 1892. Fitting the social activities of the season around her studies was an ordeal. Sixty years later she recalled her official presentation at Court in London as ‘the right thing to do and quite interesting, but very fatiguing’ for someone as shy as she was.10 She remembered waiting for three hours at Buckingham Palace in her long white dress to be called into the ballroom for her curtsey to Queen Victoria’s daughter Helena, the wife of Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, the old queen herself having long since retired to bed. ‘You couldn’t run away from a curtsey with a train. It gave you something to hold on to … But it was no wonder the presentations took so long. One has to walk so slowly with a train’, she wryly reflected.11

Her mother’s expectations of her eldest daughter increasingly came into conflict with Kitty’s desire to commit herself to music. There were house parties Sharlie wanted her to attend, Kitty must arrange a performance of a piece she had composed, and they often went to the theatre and the opera. Sharlie liked to attend the Ladies’ Gallery in the House of Commons, and occasionally took Kitty along to hear speeches by the likes of Arthur Balfour and Joseph Chamberlain, both famed debaters and leading ministers in the Unionist government elected in 1895. It must have been disappointing when Kitty’s very real hopes of a professional music career were definitively squashed by an aunt, enlisted by her mother to advise that ‘as a professional pianist I should have to concentrate so much on technique that it would have a narrowing influence on my life’.12 Whilst playing the piano was a common and largely decorative accomplishment for Victorian women, pursuing it as a career was not the course expected of the daughter of a baronet. She would also have needed to spend many more years training, probably abroad, which would have been a significant financial commitment for Sir James.

Kitty missed the 1894 Christmas term, spending the time on country house visits and practising at home, and at the end of March 1895 she left the Royal College. The family’s concerns were probably not just about the piano. Kitty’s health was never especially strong and her mother, like her later doctors, worried about her tendency to overwork. She was petite, at slightly over 5 feet tall, and strikingly pretty, with thick dark curly hair. One family friend described how Kitty had ‘the most beautiful eyes I think I ever saw. They were navy blue, and they sparkled.’13 She was talented, well read and from a good family. She might make someone a good match.

The year after Agnata’s stellar exam results, she had met the new Master of Trinity College, Henry Montagu Butler, at a performance of Oedipus Rex in Cambridge. A widower with two sons and three daughters, he was 55 when he married the 21-year-old Agnata, with twenty-six years as the headmaster of Harrow already behind him. Agnata settled into her new role as Cambridge’s leading academic hostess, and Cambridge was added to the rota of places the Ramsays visited regularly.

Kitty enjoyed ‘delightful weekends’ at Trinity Lodge, accompanying Butler’s musical sons Ted and Hugh on the piano.14 Ted was eight years older than Kitty and was not only a fine singer, but a Cambridge cricket blue and racquets champion who was starting his teaching career at Harrow. With shared interests in music and sport, it is unsurprising that they formed an attachment to each other. But she was only 20, he was her half-sister’s stepson, and it is likely that Sir James thought it too close a family connection. Perhaps Sharlie did not think a schoolmaster, even from an illustrious academic family, was ambitious enough for Kitty. By summer 1896, they had been told to break it off. It was painful for both of them; at the annual Eton vs Harrow cricket match at Lords, Ted remembered, ‘You cannot have looked at me. I kept my eyes away from you.’15 Kitty never talked about exactly how it had been made clear that their relationship could not progress, but she nursed an uncharacteristic and lifelong bitterness about it. She returned to Scotland to spend the summer safely away from amorous Old Harrovians, and Ted married someone else less than a year later.

Although life as a professional musician was now out of the question, Kitty continued to work at her composition, publishing settings of the poems in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verses. They were well received, suggesting that she had some promise as a composer. She also found a small amount of freedom when she started riding a bicycle. Within recent memory they had been a peculiar novelty in Scotland; by the 1890s, they were seen as particularly liberating for young women, allowing her to spend more time seeing friends on her own.

Kitty may have had other reasons for trying to escape from home: around this time her mother embraced a new religion. Sir James was a member of the Episcopal Church, the sister denomination to the Church of England, which used a formal liturgy and a lot of music, unlike the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Kitty loved church music and had fond memories of decorating the church in the nearby town of Alyth for Christmas together under her father’s careful direction. Christian Science was very different. The American founder, Mary Baker Eddy, taught that physical illness was a manifestation of mental error and better treated with prayer than medicine. Dolly had seen a ‘spiritual healing’ and had shared one of Baker Eddy’s books with Sharlie, who credited its methods with curing her chronic insomnia. All three of Kitty’s older sisters joined their stepmother and Baba as Christian Scientists, with Agnata becoming one of its leading members in Cambridge, and Dolly and Lily both training as healers under its doctrines. The rest of the family remained committed to the Episcopal Church, and arguments over religion became an unfortunate feature of Ramsay life over the next decade.

Sharlie continued to pursue socially advantageous connections. After meeting the 7th Duke of Atholl, who was known to appreciate a pretty face, at yet another house party, she secured an invitation to visit Blair Castle for the annual Atholl Gathering in August 1897. Kitty was not enthusiastic about going. One of her historical romances, The Bondman by bestselling Victorian novelist Hall Caine, featured the 4th duke as a tyrannical and unjust landlord in the days when the Atholls had owned the Isle of Man. She was still young enough that her impressions of the world were shaped more by books than by experience, and so she was ‘not sure how much I should find in common’ with the family.16

The historian’s daughter was more excited by the prospect of seeing the castle, just 30 miles by road from Bamff. The Atholl family, chiefs of Clan Murray, had played an even greater part in Scottish history than the Ramsays. One ancestor had shared command of the Scottish army at the Battle of Stirling with William Wallace in 1297; another was killed at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. The eldest son of the 1st duke was charged with treason after taking part in the 1715 Jacobite rising, and his younger brother George was one of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s generals during its 1745 successor. Queen Victoria was inspired by a happy stay at Blair to buy her own Highland retreat at Balmoral, and granted the duke the right to raise Europe’s only remaining private army; the current dowager duchess remained a close friend. The family’s national influence had waned since controlling the road to Inverness from Edinburgh was no longer the key to power in Scotland. But the duke still held nineteen titles, more than any other British peer, and the Atholls were semi-feudal lords on their 200,000-acre estate.

Anticipating boring company, Kitty packed a book, some Beethoven scores and her bicycle, and cycled up the long avenue from the railway station. She was met at the door by the duke’s oldest son, Lord John Stewart-Murray, the Marquis of Tullibardine, always known as Bardie. He too had three older sisters, Dorothea (known as Dertha, who was married to the army officer Harold Ruggles-Brise), Helen and Evelyn, and two younger brothers he was close to, George and James (known as Hamish). The children had all been brought up speaking Gaelic and the boys always wore Highland dress when in Scotland. Unlike Kitty and her sisters, the girls had not been allowed to go to school, let alone university, but the boys had all been educated at Eton. Bardie was now a cavalry officer whose ambition to be deployed overseas had been temporarily thwarted by an injury while fencing on horseback, and he was hoping to join General Kitchener on his next campaign in Africa.

Bardie’s parents were semi-estranged and rarely present at Blair Castle together. Duchess Louisa spent much of her time on the continent, while the duke had a succession of mistresses whom his amused children observed as they passed through the castle. Like Sir James, the duke was bored by high society and preferred to spend his time out on the hills or in his archives, working on family histories. Helen remained at home, while her parents saw Evelyn as something of a black sheep: she had been an enthusiastic collector of Gaelic folk stories who chafed at the social niceties expected of a duke’s daughter. Suffering a mental health breakdown after a bad bout of diphtheria, she was now settled in Belgium after refusing to return to Scotland – or ever see her parents again.

Bardie thought that Kitty was the Ramsay daughter with the first-class degree and was unimpressed by the prospect of a bluestocking joining the party. ‘When he saw me on a bicycle and wearing a bright cerise bow in my hat he had felt somewhat happier’, remembered Kitty.17 She had seen him before at a ball in Perth, and remembered his ‘enigmatic’ face, ‘quiet grey eyes, well-cut features, but with sandy eyebrows and moustache’.18 He noted her petite figure and was struck by her reserve. She was not like the girls he was used to; she in turn was relieved not to be sitting next to him at dinner. She cheered up after finding that a piano had been placed in her bedroom, and was asked to play for the party after dinner.

The next day the Atholl Highlanders, the duke’s private army made up of tenants and neighbours, were on full display in their impressive regalia, and Bardie invited Kitty to join him and another girl for a walk round the castle grounds. Feeling shy and a little annoyed at being left to trail behind the other two, Kitty walked off. Bardie was both offended and intrigued by her independent manner, and sought her out again. They danced much together at the Atholl Arms that evening, discovering that they had had the same teacher, and she found that he was, like her, a beautiful dancer.

Over the next few days, they rowed together on the loch, danced together again in the castle ballroom and went for a long walk up Craig Urrard, a hill near the castle. It was Bardie’s turn to surprise her by sharing ‘his love for the people on the estate and his burning desire to be of service to his country’.19 Kitty’s aims in life had been ‘to continue to work at music, to be well read, to see beautiful works of art’.20 She had had no thought of public service. She left Blair with her book and Beethoven unopened, and feeling that ‘where I had expected to find arrogance, I had found homeliness and kindness, and that in particular I had met a novel and arresting personality’.21

Bardie turned up unexpectedly at the second Perth Hunt Ball a few weeks later and they danced together again. They engineered a meeting at Crewe station while Kitty waited to change trains to go and see friends in Shropshire. In the spring they met occasionally in London, where Sharlie had rented a house at 20 Egerton Gardens, less than a mile from the Atholls’ London home. Bardie was debonair and gregarious, five years older than Kitty and much more worldly than her – and he was smitten. They started to write to each other. He was a gifted cartoonist, who often illustrated his chatty and amusing letters about military life with comic drawings of himself falling off a horse. His flirtatious teasing was not something Kitty had encountered before, and it sometimes led to hasty apologies on his part.

Gradually they became closer, making plans around occasions where they could meet again. Knowing where his pursuit was probably headed, Kitty was uncertain. She wrote frankly in an early draft of her later memoir that ‘it was a time of great indecision for me. A very strong personality was asserting itself in my life, but music was pulling against it, for I feared that if personality gained the day, I should not have as much opportunity for music as I wished.’22 His interests were quite different from hers: she joked that she would not invite Bardie to join her party for a concert at the Royal Albert Hall because ‘I might not be able to keep off musical talk, which I know is tabooed!’23

On the afternoon of Sunday, 27 June 1897, perching on the arm of a sofa at Egerton Gardens, Bardie surprised Kitty by proposing. That evening she wrote to him, ‘I do so want you to understand how frightfully happy you have made me today. It seems so wonderful and beautiful that you should care for me as you do. I can’t understand how it has all come about, and feel quite dazed with happiness.’24 They could only tell the immediate relatives whom they trusted not to spread the news. Bardie was set on joining Kitchener’s campaign in Africa, and the unmarried general would not allow engaged or married men on his staff. Bardie told his mother months before his father, knowing the duke had hoped his heir would marry someone rich – perhaps an American, as the heir to the Duke of Marlborough had done. Bardie reassured Kitty that:

You have nearly a year to think over it, + if any time before it is over you want to say ‘no’ – you can say so, + I won’t be at all nasty about it … I mean to do my best, + I hope you will bear with me, as I know I will be ‘trying’ sometimes, but as I know I really am fond of you, you may trust me to do all I can to make you happy – + I feel I am a very lucky man to be engaged (even tentatively) to you.25

In the dozens of passionate letters which now flew between them, he said more than once that he thought he cared for her more than she did for him, trying to nudge her into being more demonstrative. She told him that ‘most people find me difficult to know, but I don’t think you will, very, as you are so sympathetic’.26 She admitted that ‘I am stupidly incapable of saying what I want to, generally’ and filled her letters with the words she found difficult to speak out loud, especially given they had to be chaperoned by her mother.27 She fell more and more in love, writing:

On the surface we seem to come from the opposite poles of everything – it does show me what a powerful force love is – + how it can sweep away everything – Doesn’t it seem to you very extraordinary that you should care for me of all people? … All the same, I have not a doubt as to the happiness + rightness of the step we have taken – + the more I see of you the more certain I feel. I wish I weren’t so shy of you sometimes … I’m afraid there is a good deal of me that you don’t know – you have taken a very brave step. I hope you may never repent it.28

He received his ‘first scolding’ (of many) for not writing to her often enough, as she wrote almost daily notes to him, filled with what she called ‘drivel’ about her doings and her thoughts. She had been shocked by his first kiss, but looked forward more and more to getting married – and found the idea of waiting a year less and less appealing.

Conscious of the need to maintain the fiction of his single status, Bardie ensured that he was seen talking to other young women at social occasions, teasing Kitty with the rumours he enjoyed nurturing about his attachment to various heiresses. Even so, Sharlie had to issue denials about an engagement to newspapers, and Kitty sometimes felt uncomfortable that the secret made ‘such a barrier between me + everybody, preventing me from feeling quite at my ease with people whom I know well’.29 There were snatched moments alone together in a hansom cab and she slept with one of his letters under her pillow and always had another in her pocket.

Further meetings were interrupted by a long-planned trip to Bayreuth that summer with her mother, to much teasing from Bardie about ‘the Wagner craze [being] the worst type of lunacy.’30 Kitty loved Germany and German music and was ‘thankful to be able to say Wagner did manage to secure my attention during the performance this afternoon, for it is rather silly to come all these hundreds of miles, + then really care most about getting a letter from you at the end of it all!’31 She was careful to tell Bardie that some passers-by stopped to listen to her playing the piano in their hotel and asked where she had studied, keen to make him understand how talented she was.

After a brief stop in London, and another encounter with Bardie in a hansom cab, she was ‘so longing to get home. I hate missing any days of August in Scotland, don’t you?’32 Finding her own expertise in music, and growing out of her illness, had helped Kitty feel much happier within her family. After Fairy noticed a new bracelet and saw Kitty locking away letters in a tin box in their shared bedroom, she had the secret out of her in less than a week, and there was much affectionate teasing from her younger siblings.

The summer was spent in strenuous physical activity to work off the frustration of keeping such a big secret, playing tennis with Douglas and going for long bike rides and walks in the rain. Ever conscientious, she also started to prepare for the responsibilities of being a wife. Bardie admitted that he had lived as if he was to be a bachelor for years yet; there had been at least one incident where he had gambled too much on horses, and he avoided the temptation of racecourses for the rest of his life. He acknowledged ‘how much bigger a step too [marriage] is for you than for me, as it means coming into a new life altogether + giving up all your old habits + associations’, though she did not understand yet quite how different it would be.33 Knowing horses were an important part of Bardie’s life, she took riding lessons as well, though she ruefully admitted she was never likely to be good enough to join him hunting. She also began to show hints of a much more independent streak. ‘I am not always going to be left behind, though I know it is a convenient idea of a wife, that she should be there when you want her, + that you can leave her behind when you don’t! Thank you, that billet won’t suit me’, she wrote to him.34

In January 1898 the call which Kitty had been dreading came. Bardie was summoned to Sudan. She rushed to Folkestone to say goodbye, giving him a sprig of lily of the valley for luck, which he would keep for the rest of his life. Kitty kept herself busy with music, composing settings of more Stevenson poems, which were praised highly by The Times’s music critic, and arranging for their performance and publication. At Sharlie’s suggestion, she returned to the Royal College of Music for the summer term in 1898 to complete her diploma. Perhaps her mother realised that Kitty needed to be kept occupied, and that it might be easier to avoid questions about the engagement if she appeared to be recommitting to music.

Most mornings, Kitty was up early to start work before breakfast, but on Sundays she allowed herself to lie in and think of her secret fiancé. Kitty also spent time with Bardie’s mother and sisters. Louisa was one of the eight beautiful Moncreiffe sisters, daughters of a Perthshire baronet, who – like Kitty – had not had a substantial fortune to bring to the heavily indebted estate. ‘It made me realise how very well your Father has behaved to me, seeing that I suppose money is even more wanted now than then, isn’t it?’ Kitty mused, although she had no idea how much money would be a struggle in the decades to come.35

At the time, Bardie’s war was seen as one of liberation, to free the Sudan from the rule of the Khalifa (self-proclaimed caliph Abdullahi ibn Muhammed). It was really a colonial war to thwart French ambitions in east Africa, defend British-ruled Egypt from the ambitions of the Mahdist state to its south and avenge Britain’s notorious defeat at Khartoum thirteen years earlier. The tracking skills Bardie had learned deerstalking in the Perthshire hills were used to guide the army by night across the desert to make a surprise attack on an enemy camp.

Bardie gained a reputation for bravery and leading from the front (too much so for Kitty, who kept nervously asking him to take fewer risks in the twice-weekly letters which pursued him across Africa). He rescued a young boy from a village that had been massacred, later reuniting him with his mother, and brought home a turquoise ring he was given by one of the Khalifa’s wives in gratitude for sharing food and water. In the final battle at Omdurman, his horse was shot from under him, and he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his bravery in rescuing an Egyptian trooper. A young soldier-journalist called Winston Churchill, who was just two weeks younger than Kitty, wrote home to his mother afterwards that ‘I am just off with Lord Tullibardine to ride over the field. It will smell I expect as there are 7,000 bodies lying there. I hope to get some spears etc.’36

The duke was impressed by Kitty’s ‘pluck and good sense’ and how she had ‘put nothing in the way of preventing [Bardie’s] going out and doing his duty as a soldier’, but the most testing part of their engagement was still to come.37 Bardie was so ill with a combination of dysentery, malaria and typhoid that he immediately collapsed on returning to Eaton Place and nearly died. They were desperate to see each other, frustrated at having to wait until doctors and his mother agreed. It turned out that the many months of elaborate secrecy had been pointless: Kitchener had known all along.

Once the formal announcement was made, the newspapers praised the ‘pretty, clever, and accomplished girl’ about to marry into one of Scotland’s leading peerages.38 With the wedding date set, Kitty was now introduced to Bardie’s friends, including, for the first time, Churchill. While their fathers’ lawyers haggled over the marriage settlement and she arranged the wedding music, Kitty found time to write to Dolly and Lily, who were in Boston meeting Mary Baker Eddy, only by ‘indulging in a sore throat [which was] almost a relief ’.39 She insisted that ‘I am very happy, though too busy to think much about the future.’40

Sharlie was worried about how the Ramsays would host the expected reception in suitable style, but the Atholls’ neighbours lent their house at 82 Eaton Place. The 600 wedding presents were put on display as was customary, guarded by a detective who slept in the house. Kitty was most excited about the tiaras, but there was also ‘such a heap of lovely books … practically all things I wanted, + had not got’, as well as – she counted – ‘a distinct embarrass … a fannery’ of seventeen fans.41

On 20 July 1899, after an engagement of just over two years, Kitty and Bardie’s wedding took place at St Margaret’s Westminster, where Agnata had also been married. The duke (a lifelong member of the Church of Scotland who thought organs in church were practically debauched and who refused to celebrate Christmas) had insisted that it must be a Presbyterian ceremony; the Episcopal Sir James said that in that case he would not be able to give Kitty away. A compromise was reached and her brother-in-law Butler officiated, assisted by the minister of their home church in Alyth. Kitty took a full page to describe her ‘gown of pure white satin trimmed with silver sequined net … the bodice being trimmed with old Brussels lace with sleeves of the same’, and she wore an Atholl emerald tiara.42 It was so hot that at least one of the eight bridesmaids nearly fainted on arrival at the packed church. Parry could not be there in person to hear his Wedding March being played, but the 800 guests included most of the extended Ramsay and Stewart families, many of Scotland’s leading aristocrats, George Curzon and Lord Kitchener.

Everyone returned to 82 Eaton Place afterwards for the wedding breakfast. Even though there was a ‘huge crowd’, and it was desperately hot, Kitty wished she could have stayed longer before setting off on honeymoon. The Tullibardines first took a quiet week in the Ardennes, where they played some ‘fierce’ tennis against each other and enjoyed ‘the most complete + delicious holiday’.43 Kitty continued her education in all things Atholl when they visited the grave of the Jacobite Lord George Murray in the Netherlands, and they went to visit Evelyn in Belgium, although she refused to come out of her room to see them. ‘I leave you to imagine my chief piece of news,’ Kitty wrote to Dolly and Lily, ‘which is that I am very very happy.’44

2

The One Thought of Her Life

1899–1914

‘Lady Tullibardine herself is a living example ofwhat a woman can do without a vote.’Lord Curzon, November 19121

On return from honeymoon, the Tullibardines were given a real Highland welcome and had to stop at every village to be celebrated by the Atholls’ tenants. ‘I could never have believed in such loyalty & devotion in this 19th century, if I had not seen it’, marvelled Kitty, perhaps only now appreciating the influence of her new in-laws.2 At one stop the village poet recited a poem in which ‘he surpassed himself in scansion by managing to get the words “The Marquis and Marchioness of Tullibardine” into the last line!! It was very difficult to sit & listen to him without laughing outright!’3 Kitty accumulated eight bouquets of flowers from children while reporters followed them on bicycles from Perth, and as their carriage came up the castle drive the horses were replaced with teams of young men. ‘Then came the ceremony I had been dreading the most’, she wrote to her family, as the two oldest tenants lifted her over the threshold of the castle and ‘carried me in most comfortably as if I had been a child, with my arms around their necks!!’4 Her ‘winning smiles, pleasant face, and gracious manner’ were remarked on at each stage.5

Although she was ‘gloriously happy’ to be married, getting used to a new and much grander life was not easy. Among the extensive castle and estate staff of footmen and ghillies, the duke kept his own piper, who summoned the family and their guests to dinner every evening, and Kitty now had her own maid for the first time, ‘not a smart alarming maid, which is a mercy!’6 They lived in rooms at Blair Castle, to save money on running a separate establishment, where Helen ran her father’s household. Bardie had strong views on domestic arrangements and interior design, arranging their rooms and ensuring the spears and shirts he had brought home as war trophies (which Kitty did not like) were displayed appropriately. She had no control over their life, but the novelty of being married and deeply in love carried her through the social events at which she was much scrutinised. She felt she could cope with anything if Bardie was at her side. He, however, was already getting restless.

The British Cape Colony in South Africa had long existed uneasily alongside the Boer community descended from earlier Dutch settlers. The discovery of gold and diamonds in Boer territory eventually led to demands for British military intervention against the two Boer republics and Bardie’s patron Kitchener was preparing a huge expeditionary force. One of Kitty’s friends remembered that in a debate about ‘whether a newly-married man should volunteer Bardie took the line that he should not. Whereupon you exclaimed, “Oh! Bardie, you know you have been 4 times to the War Office about it!”’7

He was serious about his military career, which allowed him some independence from his domineering father, and Kitty was determined to be a supportive wife. After only three months of marriage, Bardie joined the Royal Dragoons as they embarked at Tilbury. He wrote to her from the converted cattle ship he sailed on, conscious of the possibility that he might not return, that ‘We have been very happy together + whatever happens nothing will ever part us now either in heaven or earth. God bless you little woman.’8 Within weeks her favourite brother, Nigel, and both of Bardie’s brothers were also deployed, as was Dertha’s husband, Harry Ruggles-Brise.

Kitty initially remained at Blair and, trying to keep herself occupied, became one of the most energetic supporters of the local Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association. The whole country was gripped by the conflict, and Kitty was, like many people, aghast at how ‘it has turned out such a much more serious thing than people seemed to expect + I certainly never thought there would be so much fighting left to do by the time you + Nigel got there’.9 But in December, the Ramsays received the worst possible news: Nigel had been killed in the disastrous Battle of Magersfontein, when the Boers halted British forces from relieving a siege at the mining town of Kimberley. Helen broke the news to Kitty in the waiting room at Perth station. Kitty immediately rushed to Bamff to be with her devastated family, where she found Sharlie ‘wonderfully brave’, drawing solace from her faith, and poor Douglas devastated because, she wrote to Bardie, ‘you know how devoted two brothers, near in age, in a family of girls, must be’.10

Grieving, and worried about Bardie, Kitty made the most of her music and found more committees happy to have the help of a new marchioness. With Duchess Louisa, she organised a series of concerts to raise money for the Scottish National Red Cross Hospital. At each of these her piano playing was the much-admired highlight (and an excuse for her to spend time on her own practising). She endured more society events too, being formally presented at Court again on her marriage, organising a ‘Grand Scotch Concert’ at the National Bazaar in Kensington, and presenting prizes at the London Highland Games.

Philanthropy and committees could have been her entire life, but she was already looking for something more meaningful, while trying to decide if they could afford for her to join Bardie in South Africa. She heard of the relief of Mafeking, which had been besieged for seven months, while she was at the theatre in London with friends. ‘At the end of the Act the whole audience got up + cheered + sang “God Save the Queen” + “Rule Britannia”. Then the streets coming home were swimming with people, marching about waving Union Jacks + cheering + singing’, she wrote to Bardie.11

Kitty finally unpacked her books at Blair and enjoyed placing them next to Bardie’s childhood books ‘+ oh how I pray there may be someone some day to read them again’, she fondly wrote, knowing that she was expected to produce an heir to continue the Atholl line.12 But their hopes of starting a family quickly were dashed, as Kitty revealed to her husband that she ‘had a great disappointment about a month after Bardie left – I think something went a little wrong, and I was rather seedy’.13 Talking about miscarriage was difficult given her character and upbringing, and she felt she needed to apologise for telling him. Becoming a mother was, she told him, ‘the one thought of [her] life, after her Bards’.14

Several weeks later, she received a tender and reassuring response: ‘Poor darling it would have been nice to think there really was some one, but it is perhaps better as it is until this worry is over. Anyhow Kit, it shows there probably will be some one some day.’15 He insisted that she come out to join him, as he ‘longed to commence our real married life together’, in their own house.16 They had barely eaten a meal on their own since their honeymoon. The duke tried to dissuade her, having become fond of his daughter-in-law, but she wanted to be with her husband and hoped to volunteer for the military hospital.

The voyage to South Africa was ‘perfectly heavenly in some ways, + horrible in others’.17 The weather was beautiful, the sea flat, and Kitty was able to play the piano in the dining saloon every morning after breakfast – but she thought that if ‘there were half the number of passengers, or rather nicer ones, it would be perfect’.18 She spent hours reading on deck, wearing a blue veil so the sun’s glare did not hurt her eyes. After six months apart, she was delighted to be reunited with Bardie at Durban. Kitty was then left on her own for two months in Natal, staying with the provincial governor, when Bardie returned to his regiment. Although she had a piano, and was trying to compose again, she struggled to escape another officer’s clinging wife and grew extremely bored by the company.