Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

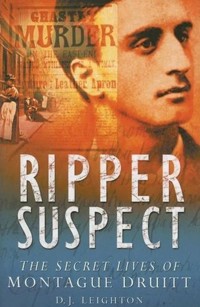

One of the most popular of all Ripper suspects, Montague Druitt appears on the surface an unlikely killer. Born into a comfortable bourgeois family, he was educated at New College, Oxford, qualified for the Bar and played cricket for a number of strong club sides. But, there was another side to the agreeable Mr Druitt. He moved in the artistic and aristocratic circles that overlapped with London's secretive homosexual culture, was summarily dismissed from his post at a boys' school, and a few weeks later was found drowned in the Thames, just months after the Jack the Ripper murders. Six years later, Chief Constable Sir Melville Macnaughten named Druitt as the murderer and gave the unhappy barrister a kind of immortality. D J Leighton has dug deep into the background to Druitt's unhappy life and uncovered a web of intriguing connections linking the eldest son of the heir to the throne, the Cambridge Apostles, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Virginia Woolf and the cricketing legend Prince Kumar Ranjitsinhji. The book is a fascinating period piece that deftly weaves together the criminal, sporting, aristocratic and homosexual worlds of late nineteenth-century London, in search of the truth behind Macnaughten's surprising allegations. This book is an excellent piece of of period crime history with a Jack the Ripper setting. It is a colourful Victorian underworld story, mixing high society with scandal, the golden age of amateur cricket and murder. It is the authoritative debunking of the case for Druitt as Jack the Ripper. This book weaves together the criminal, sporting, aristocratic and homosexual worlds of late nineteenth-century London in search of the truth behind Sir Melville Macnaughten's surprising allegations.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United Kingdom in 2006 by

Sutton Publishing Limited

This ebook edition first published in 2016 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port,

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

All rights reserved

© D.J. Leighton, 2006

The right of D.J. Leighton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8134 7

Typesetting and origination by Sutton Publishing Limited.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To Ann, with love

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

One

The Scene is Set

Two

Almost a Dynasty

Three

‘Manners Makyth Man’

Four

‘Very nice sort of place, Oxford’

Five

To Work, Rest and Play

Six

‘Modest merit but slowly makes its way’

Seven

A Happy Wanderer

Eight

A Magnificent Indulgence

Nine

Liaisons Dangereuses

Ten

Last of the Summer Wine

Eleven

The End of an Innings

Twelve

Gaylords

Thirteen

‘Curiouser and curiouser’

Fourteen

Mr Boultbee, at Your Service

Fifteen

My Uncle Knew Ranjitsinhji

Sixteen

The Judgment of Solomons

Seventeen

Joining up the Dots

Appendix

Scorecards of a Cricketer

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

So many people have helped me put together this book that it is beyond me to thank them all. However the following have indeed given me great assistance.

My thanks to

Nick Baker, Simon Berry, Marijke Booth, Peter Brown, John Carter, Peter Cattrall, Tony Connor, Susan Cornelius, Angela Crean, Ernest Crump, Ken Daldry, Caroline Dalton, Carol Ann Dickson, Steve Dingvean, David Dongworth, David Fellowes, Dave Froggatt, Robert Fyson, Brian Gibbons, Nick Gibbs, Stephen Green, Jeffrey Hancock, Stawell Heard, Bob Holmes, Neil Holmes, Clare Hopkins, Morley Howell, Jim Hunter, Trevor Jones, Margaret Knight, Bryan Lloyd, Giles Lyon, David and Pamela McCleave, James McDermott, Patrick Maclure, Prakesh Makwana, Warren Martin, Peter Nicholls, Carl Openshaw, Tim Prager, Elaine Quigley, Neil Rhind, Irving Rosenwater, Lindsay Siviter, Jeff Smith, Robert Smith, Mark Stanford, Bert Street, Sara Tutton, May Valentine, John Whittall, Richard Wileman, Murray and Myra Wrobel.

I am also indebted to individuals and organisations who allowed me to use their photographs. To anyone to whom acknowledgements are due, but who has been unintentionally overlooked, I offer my apologies and an assurance that this will be put right in later editions.

D.J. Leighton

List of Illustrations

1. Montague Druitt as a student at Oxford

2. William Druitt, Montague’s father

3. William Druitt, Montague’s brother

4. Edward Druitt and the Royal Engineers XI

5. Lionel Druitt, Montague’s cousin

6. James Druitt senior

7. Westfield House, Wimborne

8. Ridding Gate, Winchester College

9. Alfred Shaw

10. Winchester XI 1876

11. Eton XI 1876

12. Webbe Tent, Winchester College

13. Hunter Tent, Winchester College

14. Oak panelling, engraved by Montague

15. New College, Oxford

16. Alexander Webbe

17. Harold and Derman Christopherson

18. The Christopherson Brothers 1888

19. Nicholas ‘Felix’ Wanostrocht

20. The 4th Lord Harris

21. Sir Francis Lacey

22. Montague’s letter to George Street

23. Menu for the MCC Centenary Dinner

24. Duke of Clarence and friends

25. The Duke of Clarence

26. James Stephen

27. Virginia Woolf playing cricket

28. 9 King’s Bench Walk, Lincoln’s Inn

29. Thorneycroft Wharf, Chiswick

30. Montague’s gravestone

31. Sir Charles Warren

32. A sketch of the Kearley and Tonge head office

33. Entrance to Cleveland Club

34. Burgho and Barnaby

35. Amelia Lewis

ONE

The Scene is Set

In the autumn of 1888 in the Whitechapel area of east London five appalling murders took place. All the victims were prostitutes; four of them were mutilated and parts of their bodies removed. The nature of the crimes led the police to believe that they were the work of one person. Then taunting letters began to arrive, signed by someone calling himself ‘Jack the Ripper’. This was a nasty but accurate description of the murderer’s work. The killings became known as the Jack the Ripper murders, and the obloquy has helped to ensure that the case has remained high in the general public’s awareness to this day.

Since the mid-1990s, forty new books on the subject have been published. This is higher than for any other true-life crime. Patricia Cornwell’s Portrait of a Killer demonstrates the huge interest that continues to exist in the subject. The paperback edition was an international bestseller, topped the Sunday Times lists for six weeks and sold over 150,000 copies between September 2003 and the end of that year. Even today the Ripper’s frightening spectre retains its power. In May 2005 Michael Winner, writing his restaurant column also in the Sunday Times, recorded that his friend Paola Lombard disliked the small Italian village of Apricale. She thought the narrow, cobbled streets ‘were spooky’. ‘I expect to meet Jack the Ripper any moment,’ she said. Some writers and historians have listed as many as twelve victims of the Ripper, but five is the generally accepted number.

This, briefly, is a summary of those murders.

The first woman to die was Mary Ann Nichols, who was found on Friday, 31 August, at about 3.30 a.m. near a Kearley and Tonge warehouse in Bucks Row (now Durward Street), her body slashed and mutilated. Nichols had been born in 1845 in east London and by the time she was 19 she was married to William Nichols, a printer. This relationship produced five children but ended in 1880, partly because of her heavy drinking. For the rest of her life she lived mostly in workhouses, slept rough or rented the cheapest room in the worst areas of the East End. Earlier that Friday night she had boasted to a friend about her successful earnings that evening. She was drunk. Her body was identified a few hours later by her husband and the same family friend, Emily Holland. The police surgeon who carried out the post-mortem was Dr Ralph Llewellyn and the coroner was Wynne Baxter. At first Llewellyn believed the murderer was left-handed but later he became less sure. He was, however, firm in his opinion that the killer ‘must have some anatomical knowledge’. He commented, ‘I have never seen so horrible a case.’

The second victim was 47-year-old Annie Chapman, who died at about 5.30 a.m. on Saturday, 8 September, in Hanbury Street, which leads into Commercial Street. At one time she had been married, with three children, to a coachman, John Chapman, in Windsor, but they had separated in 1884 and she had moved to Whitechapel, where she sold flowers, did some sewing and worked the streets at nights. Between times she drank in local pubs. On the night of her murder she had been plying her trade to make money for her room. This time the police surgeon handling the post-mortem was Dr George Bagster Phillips. It was his view that there had been an attempt at decapitation, but in any event her body had been horribly cut up, and it was clear to Dr Phillips that the assailant had medical knowledge of anatomy and pathology. The coroner as for the first victim was Wynne Baxter and he agreed with these findings. He also drew attention to the removal of body parts.

On Sunday, 30 September, two Ripper murders took place and these became known as the ‘Double Event’. The first to die was Elizabeth Stride, who was killed at about 1.00 a.m. in Dutfield’s Yard, near the Commercial Road. Stride was born in Sweden in 1843, and became involved in prostitution at the age of 21. In 1866 she moved to London, married a John Stride three years later, and went to live in Clerkenwell. In 1878 the pleasure steamer Princess Alice sank in the River Thames and 527 lives were lost. Stride invented the story that her husband and children were among the victims, but in fact John Stride died in the Poplar Union Workhouse in 1884, three years after the marriage had ended. Elizabeth Stride now reverted to her old profession, and in the hours before her death had spent the time drinking and soliciting. Again Dr Phillips held the post-mortem and Wynne Baxter was the coroner. Death was by a cut to the throat, and Baxter believed the murderer ‘knew where to cut’. The absence of mutilation suggested to the coroner that the killer had been disturbed, but the death is still attributed to the Ripper.

On the same night about half an hour after the murder of Elizabeth Stride another woman was killed a few hundred yards away in Mitre Square. The Kearley and Tonge head office occupied two sides of the Square, so it was the second time a victim had been found near Kearley and Tonge premises. Her name was Catherine Eddowes, aged 46, and she had been brought up as an orphan in a workhouse. She settled in Whitechapel with a soldier Thomas Conway with whom she had three children, but the relationship ended in 1880 partly because of Eddowes’s alcoholism. She soon moved in with John Kelly, a labourer, and became variously known as Eddowes, Conway and Kelly. Although extremely poor, she may have been a casual, rather than a career, prostitute, and the two scraped a living doing agricultural work. The time prior to the murder is well documented as she had been in police custody until 1.00 a.m. sobering up from a drinking binge. Within an hour of her release she was dead; her throat had been cut, her body slashed and parts removed. Dr Frederick Gordon Brown carried out the post-mortem and noted: ‘I believe the perpetrator of the act must have had considerable knowledge of the position of the organs. It would have needed great knowledge.’ Eddowes’s death had all the hallmarks of an authentic Ripper murder. There is, however, a possibility that the murder was a mistake, as she may not have been a regular prostitute and could have been confused with the fifth victim.

The last of the five women to be killed was Mary Jane Kelly in the early hours of Friday, 9 November, in Miller’s Court, near Commercial Street. Her background and life were desperate. Born in Limerick in 1862, she moved to Wales and married a coal miner called Jonathan Davies when she was 16. Within months Davies was killed in a pit accident, and Kelly was introduced to prostitution in Cardiff by her aunt. In 1884 she moved to London and worked partly in a gentlemen’s gay club and partly in a West End brothel. Eventually she moved to the East End, an even more degrading environment, where she continued to ply her trade. She was last seen at about 1.00 a.m. on the Friday morning the worse for drink. Her body was found cut up almost beyond identification, and of all the murders this was the most gruesome. Dr Phillips again did the post-mortem and Mr Roderick MacDonald was the coroner.

These then are the five murders. The only motives can have been a gruesome sexual gratification, a twisted mission against prostitutes or an urge to silence certain people. All were too poor to be robbed. No one was ever charged or convicted, and, although dozens of men were interviewed, the investigation progressed no further.

There was no shortage of candidates, even claimants. The Lewisham Gazette of 7 December 1888 reported under the headline ‘Jack the Ripper in a Fish Shop’ that a John Weidon of Francis Street, Woolwich, had entered a fish shop owned by Mr and Mrs Seagain in New Cross Road. On being refused credit, Weidon began to smash up bottles and plates and threatened, ‘I am Jack the Ripper and will do for you.’ He was fined 10s (50p) with 2s costs, or seven days in prison.

Six years later the Chief Constable of the Metropolitan area, Sir Melville Macnaghten, named Montague Druitt as the murderer, but by then Druitt was dead. Nevertheless, for the last 100 years Druitt’s name has been inextricably linked with that of Jack the Ripper. This book tells the life of Montague Druitt, and the circumstances that surrounded him. It examines the validity of Macnaghten’s claim in the light of this evidence.

At the time of the murders, the East End of London had a population approaching a million, of which some 80,000 lived in the Whitechapel area. The East End as a whole was an area of abject poverty and dreadful living conditions. Charles Dickens had placed his characters Fagin and Bill Sikes in Whitechapel, the seediest part of London he knew. To see starving and dying people on the streets was not uncommon. The small squalid houses were hopelessly overcrowded, and often there was a room occupancy of six or more people. There was no large-scale industry such as mills or other manufacturing to sustain the people who would have gained such employment in the northern cities. There was some work for men in the London docks, but this was fiercely controlled so that only those perceived as being English could participate. The railways, too, provided limited work, but mostly men relied on occasional building jobs, street trading or hard manual labour, working long hours for £1 per week. Much of the population was drifting and rootless. Jewish and Eastern European enclaves were formed, and itinerant sailors up from the docks came and went. Nor did it help that gang warfare had arrived early in the nineteenth century, and by the 1880s groups of thugs such as the Old Nichol Gang, the Blind Beggar Mob, the Green Gate Gang and the Hoxton Mob were roaming the streets. Some gangs were formed along ethnic lines, and their presence added to the frightening reputation of the area.

The most common form of work for women was making or finishing cheap clothes in conditions that amounted to sweated labour. If she was lucky, a woman could earn 1s (5p) for 12 hours’ work. This would typically involve sewing on buttons, edging trousers or making buttonholes. For many their working lives began when they were still children, and inevitably these conditions led to a drift to prostitution for a large section of the society. Even married women, or those in some sort of relationship, often resorted to part-time or opportunistic prostitution. At the time of the killings the Metropolitan Police believed there were 1,200 full-time prostitutes and fifty brothels in Whitechapel alone, and many more women were casual operators. A few years earlier the medical magazine the Lancet had put the number of London prostitutes of one sort or another at 80,000. It was a figure with which the Bishop of Exeter agreed. For large sections of poverty-stricken London women it was the main industry, despite the pathetically low charges that these women made. With all this activity came high rates of venereal disease, alcoholism and early death; alcohol featured significantly in the lives of all five of the victims and the best that social security could provide was workhouses and doss houses. As there was no local mortuary, the bodies of the murdered women were taken to a shed next to the workhouse for the post-mortems, where they rapidly decomposed. Jack London, the American crime writer, called the area ‘the Abyss’. But if Whitechapel was the worst area of the East End in terms of squalor, poverty and the absence of adequate medical help, the worst street of all in Whitechapel was Flower and Dean Street. Four of the murders took place in its immediate vicinity. In 1885 it was described by James Greenwood, a social commentator, as ‘what is perhaps the foulest and most dangerous street in the whole metropolis’. Later there were some attempts to demolish it, but it took German bombers finally to remove it in 1917.

Although these conditions produced widespread crime, it was mostly petty in nature and murders were unusual. The year before the Ripper killings, there was none in Whitechapel. However, in 1888 at least seven prostitutes were killed. Something peculiar was going on, and it led the police to the view that all or most of the crimes were the work of one madman. As a community Whitechapel did not appreciate its increased notoriety. Bands of men were formed into vigilante groups, and the women raised a petition of 4,000 signatures in three days, which they succeeded in bringing to the attention of Queen Victoria. Her reply was not especially helpful. A spokesman bore the message that ‘the Queen is desirous that those interested should know how much she sympathised’. Up to now Victoria’s record for espousing women’s causes was non-existent. A few years earlier she had proclaimed: ‘Feminists ought to get a good whipping. Were women to unsex themselves by claiming equality with men, they would become the most hateful, heathen and disgusting of beings and would surely perish without more protection.’ After the fifth murder she did take matters more seriously and sent an instruction to Prime Minister Salisbury: ‘This new ghastly murder shows the absolute necessity for some very decided action.’ Earlier the Queen had acknowledged conditions in the East End. In 1883 she wrote to Prime Minister Gladstone asking him to ‘obtain more precise information as to the true state of affairs in these overcrowded, unhealthy and squalid abodes’. Public meetings, sometimes with religious overtones, defended the people of east London, whose reputation anyway was most unattractive. One gathering ended by proclaiming that the meeting had ‘no confidence in the present management of the police’. The docklands trade unions waded in with an offer to ‘place seventy trained working men on the streets of Whitechapel from 10.00 p.m. until 7.00 a.m. Such men full of courage and endurance might well prove to be the means of capturing the villain.’ The unions did expect some sort of financial reward for their members’ efforts, however, and when this was slow in materialising the offer faded away.

Despite the efforts of such groups, sometimes not entirely altruistic, to put an end to the murders and restore a vestige of self-respect to the area, the East End was and remained an area of awful social conditions. It was characterised by nasty little gas-lit streets, grim, damp tenements and uniform deprivation. This created the environment in which hundreds of women put their lives at risk every night. As a contemporary writer put it, ‘they sell themselves for thru’pence or tu’pence or a stale loaf of bread’. The October 1888 edition of the British Medical Journal thundered its condemnation of the East End’s conditions: ‘We have had the heavy fringes of a vast population packed into dark places, festering in ignorance, in dirt, in moral degradation, accustomed to violence and crime, born and bred within touch of habitual immorality and coarse obscenity.’ It was a most legitimate summary.

TWO

Almost a Dynasty

On Saturday, 8 September 1888, Montague Druitt was a worried man. He was playing cricket against the Christopherson Brothers’ team in the end-of-season inter-club match at the Rectory Field, Blackheath, and it was his turn to bat. Two wickets had gone cheaply and it was not yet midday. Opposing him was the former England opening bowler, Stanley Christopherson, who was fast and accurate, but batting had never been Montague’s main strength, and at no. 4 in the batting order he did not feel equipped to deal with the threatening pace. He was right, and Christopherson soon sent him on his way back to the pavilion. Later on Montague redeemed himself by taking 3 wickets and finishing on the winning side. His last act on a cricket field was to bowl Derman Christopherson, the father of the side. Moments later Frederick Ireland bowled the youngest son, also called Derman, and the match was over. In the usual highly convivial end-of-season celebration everyone would have forgotten Montague’s brief innings, and anyway he was a popular and respected member of one of the leading amateur sides in the land. Hopefully he enjoyed the moment, for unbeknown to him at the age of 31 his cricket career, the joy of his life, was over. He would never set foot on a cricket field again.

Meanwhile, 6 miles away in Whitechapel, Dr George Bagster Phillips, the Divisional Police surgeon, was having a much worse day. At 6.15 a.m. he had been woken by Inspector Joseph Chandler of the Metropolitan H Division summoning him to deal with the dismembered corpse of a woman. Dr Phillips, an experienced surgeon in his fifties, drew up a gruesomely anatomical account of what lay before him. His report on the dead woman Annie Chapman was presented at the inquest five days later. Dr Phillips stated that the removal of some body parts would have needed professional skills, and if he had been carrying out the surgery for an autopsy it would have taken him an hour. As if Dr Phillips’s task was not unpleasant enough, he received a reprimand for not relating even more details of the wounds.

While Montague was taking some brisk and enjoyable exercise at the Rectory Field, Dr Phillips was writing his report. Such were its contents that after twenty-six blameless years as a police surgeon he was no longer enjoying his work. But over the next three months, life for Dr Phillips was to get much worse, and by the end of the year his unenviable, if small, place in criminal history would be ensured. It was to be his grim duty to attend the inquests for four of the five victims; his findings and opinions were central to the subsequent hunt for the murderer.

Montague John Druitt was born on 15 August 1857 at Westfield House in Wimborne, Dorset. Six weeks later he was christened at the Minster by the Revd William Mayo, a brother of Montague’s grandmother. The Mayo family and its connections became of interest much later in the quest to unravel the legends and mysteries of Montague’s life and death.

Montague was the third child of William and Ann Druitt. William was a doctor and surgeon with the largest practice in Wimborne, which he had mostly taken over from his father. Both were members of the Royal College of Surgeons. Ann had been brought up close by in Shapwick also in a professional family and was well off in her own right. At the time of their marriage in June 1854 she was 27 and William ten years older. They soon set about raising a family and produced seven children in the next seventeen years. Their first child was a girl, Georgiana, followed a year later by William Harvey (Ann’s maiden name) and then Montague. Four more children soon followed – Edward, Arthur, Edith and lastly, in 1871, Ethel.

Westfield House was a fine, solid early Victorian manor set in a magnificent six-acre estate, which included stables, where the horses and carriages were kept, and two cottages for the servants. Today it still stands between Westfield Close and Redcotts Lane, divided into eight flats. Apart from the property of Lord and Lady Wimborne, it was the best house in the town.

Nearby, Wimborne Minster still bears an impressive five-lighted window presented to the church by the family of William and Ann Druitt. It is in the south transept and, appropriate to a doctor, has as its theme the treatment of the sick. St Luke, Isaiah, St Christopher, St John and Ezekiel are all depicted in various acts of healing. It was dedicated in the early 1890s and was probably the work of either John Clayton or Nathaniel Lavers, two of the best stained-glass glaziers of the time. Some years earlier a smaller window had been dedicated to William Druitt’s father, Robert. This window shows St Luke and St Cuthburga, the foundress of Wimborne Minster. Abbess Cuthburga, the sister of King Ine of Wessex, separated in mid-life from her husband, Aldfrith, King of Northumbria, to set up the community at Wimborne. Cuthburga is still the ecclesiastical name for the parish. The windows serve as a reminder of the status of the Druitts in the town and of their commitment to the church and the medical profession.

Montague was brought up in style and comfort in a gentle pastoral setting, quite unaware that not all Victorian England, especially the East End of London, was similarly privileged. William Druitt was a disciplinarian with traditional Victorian views. He was a governor of the ancient Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, which had been founded by Lady Margaret, the mother of Henry VII, in the late fifteenth century. He was a trustee or treasurer of many local charities at the Board of Guardians, was Chairman of the Governing Body of the Minster and was, according to the Wimborne Guardian, ‘a strong churchman and a conservative’. He was also a Justice of the Peace. The only story to cloud his reputation was a rumour that, when his sons had left home, he used the spare rooms as a private mental hospital for patients from the aristocracy. In keeping with the times, the four sons were duly sent to leading public schools, and an Oxford education would be expected to follow. Montague went to Winchester, Edward to Cheltenham, Arthur to Marlborough and William to Clifton. At Clifton William was a pupil of John Percival, Clifton’s founding headmaster. The girls’ education is not recorded, but, again in keeping with the times, they were probably sent to local day schools or given a governess.

Up the road at Christchurch, William Druitt’s brother Robert, also a doctor, was bringing up his own family of ten children, including a son, Lionel, who would be suspected of playing a part in the intrigue that surrounded Montague after his death. Another cousin of Montague, Herbert Druitt, became fascinated by local history and built up a huge collection of artefacts. His obsessive collection included fossils, stuffed birds, books, papers, china, paintings, drawings, photographs, fashion plates, brass rubbings and textiles. His ambition was to open a museum. Herbert died in 1943, but eight years later, when all the material had been sorted, the Red House Museum was opened and remains so to this day. It stands near Christchurch Priory on the site of the old parish workhouse. Prized among its paintings is a small oil by Henry Scott Tuke, entitled The Cabin Boy. It has always puzzled the museum’s curator Jim Hunter how a picture of such quality came into Herbert’s possession. The Christchurch public library also bears the Druitt name in large letters over its doorway.

At home at Westfield House, the main influences on Montague’s life would have been his father, mother and his elder brother William. He would also have had an interest in Edward as he grew up, mainly because of his cricketing skills, which probably exceeded his own. Edward played a full season in the Cheltenham side at the age of 16 and was the leading wicket-taker. Charles Alcock, the editor of James Lillywhite’s Cricketers’ Annual, described him as ‘a straight medium paced bowler. A fair bat; lacks energy’ – a strange comment on a man who was to spend his next thirty years in the British Army. The next year Alcock was kinder and described his batting as ‘greatly improved’ and recorded that he had the ‘best bowling analysis of the year’. At Cheltenham he was highly regarded. The school magazine, The Cheltonian, noted in its issue dated March 1876 that ‘Hayes and Druitt are going up for examination next term, so will not be available to play in all cricket matches, which will weaken the eleven’.

Like Montague at Winchester, Edward occasionally confronted a player who would prove exceptional. In 1875 in a match against Marlborough Edward bowled against A.G. Steel, who as England captain retained the Ashes. Steel also took two centuries off the Australians and served as President of MCC.

Edward was the only one of the brothers who did not go to university. From Cheltenham he went to the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and then into the Royal Engineers. Both establishments afforded great opportunities to play good cricket. Edward served with the Royal Engineers until his retirement from the army in 1909; he had reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. Afterwards he worked for several years for the Board of Trade investigating railway accidents. This must have seemed mundane after the camaraderie of an army life. However, he and his wife Christina had to endure one personal tragedy: on 9 May 1915 their only son, Edward, was killed at Ypres. He was a 2nd Lieutenant with the 2nd Royal Berkshire Regiment, and like his father he had made the army his life. His death was recorded in The Times, 17 May 1915, under the headline ‘Fallen Officers’. The same report carried details of the death, also at Ypres, of Major the Honourable Clement Mitford, of the 10th Hussars, traditionally the regiment of aristocrats and royalty. He was the uncle of Diana Mitford, later to be Lady Oswald Mosley.

Montague’s elder brother, William, was also a useful cricketer. Like Montague he played for Bournemouth and Kingston Park, and in a match at Bournemouth in 1877 he dismissed Montague. When he went up to Oxford, he was good enough to play in the Freshmen’s Match, a trial match for those in their first year at Oxford. William took 4 wickets, but it was insufficient and he played no further visible part in university cricket. Montague had already left home to become a boarder at Winchester when Ethel, his youngest sister, was born early in 1871. Movement and change characterised life at Westfield House as the seven children came and went between school, university and their careers. For Montague the new challenge of Winchester and beyond had begun.

THREE

‘Manners Makyth Man’

When Montague set off to Winchester College in January 1870, he did so as a fee-paying pupil and entered Fearon’s, the house named after William Fearon, a housemaster who later became headmaster. After two terms Montague achieved a scholarship, coming third among all scholars, and this relieved his father of paying his fees. He had been identified as one of the brightest boys, and bypassed the junior part of the school to enter College in the middle section. He progressed very well, and attained the distinction of being taught by the headmaster, Dr George Ridding, for the last three years. Academically he was a star. It was the same Dr Ridding who had given cricket at Winchester an enormous boost when, in 1869, he presented the school with a piece of ground called Lavender Meads. It became the new cricket ground, to be known as Ridding Field, and Montague was one of the lucky beneficiaries.