Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

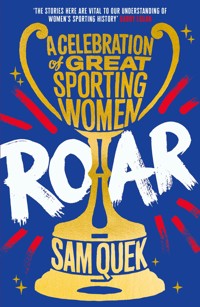

*SHORTLISTED for the Vikki Orvice Award for Women's Sports Writing at The British Sports Book Awards 2024* 'The stories here are vital to our understanding of women's sporting history' GABBY LOGAN From the tennis court to the boxing ring, the athletics track to the football pitch, the visibility of women in sport has been gathering pace. Women's competitions are increasingly popular. In Roar Sam takes a deep dive into the experiences of some of sport's most high-profile female athletes - some have overcome heartbreaking adversity to reach the top of their game; others have succeeded in the face of prejudice. Like Sam, all have been propelled by sheer grit and determination to succeed. Many now campaign for women's equality and acceptance in sport, knowing the confidence it can bring young girls and the message that they can achieve anything. Featuring a series of candid interviews from some of sport's most successful women, Sam lifts the lid on what it takes to reach those heights: from coping with puberty to foregoing teenage fun to pursue a dream; from the punishing physical training schedule to the mental power needed to win or bounce back from defeat; and coping with the pressure of the media spotlight. And, what it feels like in that magical moment when you step up to the podium knowing every sacrifice has been worth it. Roar is a celebration of the bold and fearless - the women empowering future generations to follow in their footsteps - but it is also an inspiring look at how sport can change lives and challenge society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 367

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sam Quek MBE is an internationally successful field hockey player who was a vital member of Great Britain’s women’s hockey team that won the gold medal at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. This was the first ever Olympic gold medal for Great Britain’s women’s hockey. Sam is now a full-time presenter of the BBC’s daytime

TV show Morning Live and in 2021 presented the Tokyo Olympics live on the BBC. Also in 2021,

Sam became the first ever female team captain on Question of Sport.

Sam lives with her husband and their two children.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Sam Quek, 2023

The moral right of Sam Quek to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 917 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 916 6

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my daughter Molly, I dedicate this book to you with hope that the tenacity and dedication of the amazing women noted within its pages inspire you to do great things.

May their trailblazing make your own sporting path, should you choose to take it, that much smoother.

(And to my son Zac, I love you just as much as Molly, but I dedicated this book to her specifically, as you were born at a time when women’s sport still struggles to achieve parity with men’s sport. Hopefully by the time you are old enough to read this book, things will be on a much more level playing field.)

Contents

Foreword: Gabby Logan MBE

Introduction: Sam Quek MBE

1 Making History – Paula Radcliffe MBE

2 Into the Unknown – Amy Williams MBE

3 Unlocking Potential – Dame Katherine Grainger

4 Never Give Up – Dame Sarah Storey

5 Strength and Power – Fatima Whitbread MBE

6 In the Moment – Sky Brown

7 Breaking Down Barriers – Shaunagh Brown

8 For the Love of Sport – Sheila Parker MBE

9 Trust and Responsibility – Kate Richardson-Walsh OBE

10 Digging Deep – Rebecca Adlington OBE

11 Conquering Expectations – Christine Ohuruogu MBE

12 Building a Legacy – Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson DBE

Afterword: Sam Quek MBE

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

Gabby Logan MBE

TV presenter

When Sam asked me to write the foreword for Roar: a Celebration of Great Sporting Women I was delighted. I’ll never forget travelling to work at the athletics stadium at the Rio Olympics in 2016. We were all glued to our phones watching Team GB winning that women’s hockey final. It pushed the News at Ten back – very little manages to do that – and I remember saying to my colleague Denise Lewis that it felt like one of those big seminal occasions in women’s sport. Feeling the enormity of that powerful national moment and witnessing the infectious team spirit of which Sam was a part was really something special.

It’s achievements like that which have incredible resonance in all sport, but it’s been brilliant for me to have witnessed throughout my career the rise of more of those awe-inspiring moments in women’s sport. As a schoolgirl I was a competitive gymnast before moving into broadcasting full-time after I graduated from university in 1995. To say the landscape was different back then would be an understatement. We watched women playing tennis, competing on the athletics track and playing golf at a high level with some of the attention their male counterparts enjoyed, but equal visibility across a wider range of sports was a long way off.

Even in my profession, there was a prevailing idea that sport and sports presenting was a largely male space. If women weren’t seen competing then why would we want to talk about sport? I guess I was lucky that when I debuted on Sky Sports it was at a time when the door was opening for women, if only slightly. I wanted to show viewers that not only could I do my job well, but also that women could have an interest and a passion for sport and that door could be opened further.

Yet as I write this foreword in 2023, I doubt even I could have imagined that I’d ever witness the Lionesses storm to victory in the 2022 Women’s European Championship with the top peak TV audience of the year – a record 17.4 million in the UK. Or, that only last week I’d be standing on a freezing-cold touchline at the women’s Six Nations rugby tournament in front of a sell-out crowd. A decade ago women’s teams would have played to a handful of spectators – one man and his dog, I joke. Now the atmosphere is electric, the quality of play is fierce and the momentum behind women’s sport is accelerating fast.

None of this has come easily. It wasn’t until I began presenting women’s football in 2007, for example, that I started to educate myself fully about why, when I was growing up, girls weren’t seen playing football. A fifty-year ban – more of which you’ll read about in this book – prevented us from doing so. Yet the more the game has received coverage, plus the support and investment that has been channelled into it, the more it has flourished. This model for success is now trickling down to other sports, whether it’s team games or individual categories. Admittedly progress has felt like a giant tanker turning, but thankfully a sea change is happening.

Positive action has underpinned that change. The introduction of National Lottery funding in 1997 for elite sport was a game-changer for women. On the back of that investment, the London 2012 Olympics created many female role models and highlighted sports – such as cycling and rowing – where traditionally women were not celebrated. The impressive female medal haul that followed meant women could no longer be ignored. Women’s sport was no longer the poor relation. Instead, it was a force for good. Investing in women could no longer be a box-ticking exercise. Instead, it was a huge opportunity for governing bodies, sponsors, broadcasters and fans to champion women – it’s an opportunity I believe will be unlocked further in the future.

I’ve also experienced a cultural shift. Sport is tough and elite sport is really tough. There’s no easy way to the top. Arguably society has protected girls from the rough and tumble of sport – the highs and lows of competition involve getting hurt both physically and emotionally. Yet what the world is starting to see is that women can inhabit that space, but do it in their own unique way and on their own terms.

Moreover, questions are being asked over access to sport which has more commonly been better for boys, whether that’s at school or within the local community. Inspired by national successes in a range of disciplines and the ensuing enthusiasm of daughters, grand-daughters, nieces and sisters, more people are asking what’s available for girls.

Every woman featured in this book, including me and Sam, started out by simply loving sport. And, as you’ll read, sport isn’t all about the elite level. Although the stories in this book provide an honest, at times gritty yet exhilarating insight into elite competition, each woman’s experience is about so much more than that. Sport is about being mentally fit and healthy. It’s about overcoming hardships; it’s about developing self-confidence and self-esteem. It gives us the best life lessons about how to work in a team, how to cope with failure, and how to bounce back and achieve success. It’s about knowing that when we put the effort in, we get so much out.

Having got to know Sam since her 2016 Olympic success, I understand how she found her own confidence through sport, and how passionate she is about being a positive role model and an ambassador for women’s sport. The stories she has gathered here are vital to our understanding of women’s sporting history – where we’ve come from and where we are going – and will resonate way beyond these pages.

Gabby Logan

INTRODUCTION

We Can Do Anything

Sam Quek MBE

HOCKEY PLAYER

In 2016 I stood on an Olympic podium with fifteen teammates united in one crazy, unbelievable moment. As a member of the British women’s hockey team, we had just won a historic victory again the Dutch to take the gold medal at the Rio Olympics. The nerve-shredding adrenalin of a match decided on penalties was still coursing through me as the noise of the thousands-strong crowd exploded around the stadium.

At the game’s climax it was our defender Hollie Webb who stepped up to take the final penalty shot. Everything we had worked for as a team, everything we had practised time and again in training, rested on eight short seconds. It felt like a lifetime. As she dribbled right, then left towards the Dutch keeper, finally landing the ball in the back of the net, disbelief, joy and relief flooded through me. With my arms wide open, I ran towards my teammates and we hugged and jumped and danced. Afterwards, when I scanned the stands to find my mum, dad and my now-husband Tom, they were standing with tears streaming down their cheeks.

For the fans at the Deodoro Stadium that day, plus the ten million people watching on TV around the world, it was a tournament that became the defining event of UK women’s hockey. Only two years before, we had come eleventh in the World Cup. We were ranked seventh in the world. We had beaten the Dutch previously but they were seen as the dominant, invincible force. Plus, the GB women’s squad had never brought home a gold medal from an Olympic final.

Yet from the outset everything had clicked into place. Not long after we touched down in Brazil we found ourselves playing in perfect harmony. ‘Shall we just call it a day now?’ our coach Danny Kerry had joked after he blew the whistle on our first practice session. Normally in pre-tournament warm-ups, your body feels heavy and your lungs ache from the flight. Play feels stodgy and the ball clumsily pings off your stick as you try to trap it. Not this time. This time the ball moved smoothly. We moved smoothly. Something weird was in the air and we knew it. Danny knew it, too. We were a winning team before our gold medals were ever placed around our necks.

Fast-forward six years and I was sitting in the stands at Wembley waiting to watch the England Women’s football team file on to the pitch. I’d travelled to see the Lionesses’ final against Germany in Euro 2022 with my friend Kirsty – a fellow Rio Olympics squad member and someone I’d known since we were teenagers, working our way up through the junior ranks in international hockey.

On the way there, we’d paused to take in the sweep of Wembley Way and watch the crowds swarming towards the stadium to the backdrop of car horns beeping and flags proudly displaying the St George’s Cross.

‘Can you believe it?’ we said to one another. We knew the game was a sell-out – with England in the final it had become one of the hottest tickets in town – but there was something about being slap bang in the middle of it, noticing young girls smiling and laughing with their families and dressed in their England strips that stopped us in our tracks.

Once inside the stadium, that feeling only got stronger: ‘Wow! All of these people are here to see women’s football? Oh. My. God. This is amazing,’ we said. In fact, the 87,000 fans poised to watch one of the most thrilling games of the season turned out to be the most to witness any men’s or women’s European Championship final in the UK’s sporting history. As for the game itself, at times it left us both speechless. The entire tournament had already been marked out by its breathtaking quality of play, but this felt like women’s football had reached another stratosphere. The Lionesses played with an effortlessness, confidence and freedom that reminded me of how we felt during our Rio final. Similarly, the match came down to the wire with forward Chloe Kelly stabbing home the final goal in the 110th minute in extra time. Everything clicked. It sounds cheesy, but it really is the stuff that dreams are made of.

For me, it was Chloe’s winning-goal celebration that summed up everything, and not just for women’s football, but for the whole of women’s sport. As she turned and ran into the penalty area, she tore off her jersey to reveal her sports bra, swinging her strip around her head as she ran. One moment of unstoppable, irrepressible joy that got her a yellow card, but in my view it was a stroke of genius. I’d be surprised if there was a woman watching who didn’t think, ‘Go on, girl!’ Overnight, it became the defining image of a new era. To me it said, ‘I’m a woman. We’re women doing great things and this is the female body achieving great things.’

Women’s sport has never looked or felt so good as it does now, in 2023. In the past decade or so, individual successes and team victories have taken centre stage in ways I couldn’t have imagined at the start of my career. Following the introduction of National Lottery funding for elite sport in 1997, the London 2012 Olympics saw a roster of women become household names. Heroines like heptathlete Jess Ennis-Hill, rower Katherine Grainger, boxer Nicola Adams and cyclist Laura Kenny were all elevated to gold-medal superstars. Two years later, England’s triumph at the 2014 Rugby World Cup became a catalyst that has led to the Roses dominating the leaderboard in the Six Nations Championship. In tennis, the sight of an eighteen-year-old Emma Raducanu smashing it at the US Open in 2021 is another history- making moment imprinted on my brain – the line-up of stellar achievements is just too long to list here.

But the reality that women caught up in the sheer exhilaration of loving their sport has not always been embraced may surprise many of those young girls that Kirsty and I watched as we made our way down Wembley Way. Women’s sport as we are enjoying it now is only the result of many, many women breaking down the barriers that have either prevented them from participating in sport or stopped them from being visible.

Sadly, history is littered with so many stories of women being banned from sports such as boxing, football or running, or having to meet in secret just to compete together. In the past, sport for women has been labelled unfeminine, socially unacceptable or too dangerous. I only need to look to my own sport – hockey. A match report from the first ever league game in 1890 says it all: ‘When the teams took up their positions they made a pretty scene… the spectacle was quite animating, not to say charming.’ Today, I dare any pundit to write that about the truly awe-inspiring women who have sweated, bled and beamed their way into the history books.

But while our changing landscape feels far more positive, some hangovers from that outdated era still exist. In 2022, the Northern Ireland women’s football manager Kenny Shiels attributed his side’s loss to women being ‘more emotional’ than men. In other words, women are still not seen as strong enough for the cut and thrust of competitive sport. Judging by archaic comments like that, we still have a long way to go.

There are other challenges, too. Fears that any gains made in achieving parity in women’s sport may have been wiped out by the Covid-19 pandemic are real. Cancelled seasons for women’s sports resumed long after men started playing again. Lack of access to training equipment and space to train during lockdowns also put a disproportionate number of women on the back foot, given that more female teams lack dedicated training facilities. And funding and sponsorship that existed pre-pandemic is not guaranteed going forward.

Elite sportswomen are also demanding more attention is given to issues that uniquely affect them. Many more now want to train and compete during pregnancy and after childbirth, yet only a handful of governing bodies have woken up to how this might be achievable. Scientific study around women’s physiology is also only just scratching the surface about how periods or menopause can affect women athletes throughout their careers.

Debate about the inclusion of transgender athletes alongside balancing fairness and safety in sport for biologically female athletes is also a live issue. It’s a conversation that has become polarized in the media, yet deserves open, nuanced and ongoing discussion. Like many of the female athletes I talk to, I want to guard against the risk of unfair advantage when it comes to athletic ability. However, I believe both inclusion and fairness at all levels of sport are possible.

Away from elite competition, participation of schoolgirls in sport remains significantly lower than that of boys. In so many of the schools I visit, girls tell me that being judged and lack of confidence are reasons why many lose interest in sport as they become teenagers. That sport is still not considered cool for girls is a real bugbear of mine, especially when there’s so much raw talent out there turning outdated stereotypes on their head.

Girls being denied access to certain sports at school, such as contact games like rugby or football, is also holding us back. As I write, the UK government has pledged to make the same sports available to both boys and girls in schools, wherever wanted. It’s an encouraging move and it will be interesting to see how much take-up there is. But a historic lack of visible female role models in those sports may also be another reason why progress has been slow. To me, it’s not rocket science. After the Lionesses’ Euro 2022 win and the coverage it received, there was a dramatic increase in sporty girls dreaming of their own successes in years to come. The phrase ‘If you can’t see it, you can’t be it’ has never rung so true. And role models aren’t always found at the elite level. All of the amazing women interviewed for this book got inspired by teachers, family members, coaches or women they competed with in their local clubs. Participation and enjoyment always begin at the grassroots.

Thankfully, the appetite for watching women’s sport is growing. In 2022, broadcast audiences doubled from 17 million the previous year to 36 million. Pre-pandemic levels were even higher. In 2019 an estimated 59 per cent of viewers had watched women’s sport on three or more occasions compared to 57 per cent in 2022. A constantly improving standard of play, the knock-on effect of which is often increased viewing figures and growing sponsorship interest, is in part down to sustained investment and it’s made women’s sport more exciting than ever. That said, worldwide print and broadcast coverage still averages a pitiful 4 per cent.

Sponsorship deals are also improving but progress is slow. Similarly, the number of women moving into leadership positions in governing bodies and sports associations is increasing, but not fast enough. As for what we know about the journeys of many of Britain’s sportswomen, there is still a frustrating lack of exposure. Mainstream sports media is awash with stories of men’s sports. Fans know their favourite competitor’s histories and the twists and turns of their careers. They root for their heroes because they feel they understand them and know their backstories.

The same cannot be said for most sporting women. Flick through the pages of most newspapers and you’ll still find reports on how women look while they are playing sport, not their actual performance. As for women’s stories, there are so many tales of bravery and determination, hardship and personal sacrifice. It’s the reason why I wanted to put together this book. Most sports fans see and remember athletes clutching medals or trophies, laughing, crying or singing the national anthem. While those snapshots are a vital part of the experience for any athlete reaching the top of their game, success stories are never simply about those moments.

Behind every elite sportswoman’s success or gut-wrenching loss is years of hard graft: there’s the marginal gains built from season to season; the intense periods of self-doubt; the setbacks due to physical injury or mental health; the overwhelming pressure of being thrust into a media spotlight. Everyone has a compelling story to tell, and I believe it’s more important than ever that women from many different backgrounds and with a variety of experiences share these stories to inspire every girl out there who may want to take up sport as a profession or as a lifelong hobby.

In sitting down with some of the most influential women in sport, I wanted to show elite sport’s gritty reality alongside its triumphs. I’ve learned so much through these conversations. Javelin thrower Fatima Whitbread tells the story of how sport saved her from a devastating childhood. Marathon champion Paula Radcliffe sheds light on the agony of the long-distance runner. Hockey captain Kate Richardson-Walsh speaks about how coming out as gay informed her approach to leadership and building teams. Para-athlete Sarah Storey discusses balancing a medal-winning career with being a mum. And, my youngest interviewee skateboarder Sky Brown gave me so much hope for the future. Her mantra of ‘girls can do anything’ is infectious. Each one of the sportswomen featured here has helped women’s sport evolve to where it is today.

I only have to look back at how I came to be on that podium in Rio in 2016 to understand how some of those personal battles and wider prejudices discussed in this book have affected me. My own passion for sport didn’t begin in hockey at all, but in football. Growing up in the shadow of Liverpool Football Club in the 1990s, I was handed my first Reds strip at the age of seven. That year, a 23-year-old Steve McManaman lifted the Football League Cup with two goals in the 2-1 win over Bolton at Wembley. Glued to the TV with my family, I was hooked.

Back then, footballing heroines didn’t exist. Of course, they were out there and my interview in this book with the first ever England captain Sheila Parker was a truly humbling experience. But girls like me didn’t know about women like Sheila and we certainly didn’t see them on TV. Truly, I would have loved a Lioness to idolize. As for seeing role models who were mixed-race Chinese-British like me, that would have been off the scale. Instead, I had to make do with the lads catapulted from my home-town streets of Toxteth and Bootle into first-league legend.

I guess I was fortunate in that my twin brother Shaun shared my passion. We had goalposts set up in the garden and as I played with him and his mates I pretended to be ‘Macca’, shouting a running commentary as I raced down the wing: ‘McManaman crosses for Fowler, who shoots and scores!’ When I was nine, I started going with him to play for my local team, the West Kirby Panthers. The fact that it was a boys’ league meant nothing to me. I played a couple of times in midfield and had the time of my life. But it wasn’t long before I discovered that I wasn’t welcomed by everyone.

When I showed up with my dad and joined in the pre-match practice, no one cared, but the minute I got my kit on ready to play, the comments started. From the sidelines I heard things like ‘Oh my God, there’s a girl playing football!’ A few weeks went by before my mum got a message from the local FA saying that complaints had been made about a girl playing football. From then on I was banned from the children’s league.

Naturally, my mum wasn’t going to accept that and complained to the national FA, but by the time I was given a temporary reprieve until I reached eleven – at that time the age at which girls were allowed to play in boys’ teams under official FA rules – it came too late in the season. Stubbornly, it didn’t stop me turning up every week and warming up with the boys. But before each match I was forced to slide my tracksuit bottoms back on and watch from the sidelines with my dad. Even now, I remember that feeling of being gutted I was stopped from participating in a sport that I loved.

Eventually, I joined Tranmere Rovers girls’ team, one of only two girls’ teams in my area. By then I was also excelling at hockey. And like many of the women featured in this book, such as the swimmer Rebecca Adlington who as a kid just loved the water, my career did not start by my thinking it was going to be a career at all. I thrived at sport and I just wanted to play.

Why hockey? I got into it purely because during school lunchtimes there were clubs for all sorts of sports. Mum had always instilled in me the ethos that while winning in sport was the main goal, enjoying myself was just as important and when I tried hockey, I naturally slotted in. I began in centre midfield and loved the pivotal role of helping with defence and setting up attacks. By the age of fourteen, I was playing in the women’s league, running practice alongside football plus juggling my studies.

But for every successful sportswoman, there are people who have spotted your potential often when you couldn’t. These unsung heroines and heroes fill these pages. For ex-England rugby player Shaunagh Brown it was the teachers who told her she was special. For wheelchair athlete Tanni Grey-Thompson it was her first coach. For me, one was a PE teacher called Mrs Concannon. She took me aside when I was twelve and told me I could go places with my hockey but I needed to join a club. As an ex-Scottish hockey international, she had some good advice. She also directed me towards a club that was in the national league rather than one local to me. She saw a pathway into competition for me a good four years before I made the decision to quit football and concentrate on the game that would end up defining my life.

That sport was not cool for girls was also a constant theme when I was growing up. While I was fortunate to have teachers who understood the progress I was making and helped me balance sport with my studies, peer-group pressure made life more difficult. I was Sam the sports geek who couldn’t hang out in town with my mates or stay out late at parties even when I wanted to. Aside from a handful of girlfriends whom I’m still in touch with today, kids at school didn’t understand what I was doing or to what level. Shaunagh Brown and Sarah Storey also speak eloquently about being ‘different’ at school and having to navigate the bullies.

Playing in a team was also challenging at times. Although now I believe that sport is one of the best ways to break down any barriers, at football practice I was teased for being the only girl who attended a private school. ‘Here’s the posh girl,’ some would say. At hockey, it was my mixed-race heritage that sometimes became the focus for ridicule. Yet when we were all on the pitch we had one goal: to win. Even if you are under-confident and shy, sport forces you to communicate and work together, to win together and to lose together – it’s a crucial element of success that I also discuss with England hockey captain Kate Richardson-Walsh.

And let’s not forget the uncontrollable nerves of turning up to a club or to trials or to your first international call-up to play with a team you’ve never met. Sprinter Christine Ohuruogu describes that experience perfectly, as do other women in this book who remember those nerve-wracking milestones like they were yesterday. I am no different.

Having trialled for the England Under-18s team, I performed well enough to play for the Under-21s, and it was off the back of that that I was first earmarked for the Women’s GB team. Oh. My. God. That’s when reality hit. Before training at the National Sports Centre in Bisham Abbey in Berkshire, after a three-hour journey, I could barely eat breakfast. Instead, I arrived one hour early and sat with my dad in the car park feeling waves of nausea washing over me. When I eventually entered as the newbie, I worried about everything: from what I was going to eat for lunch to how quickly I was going to put my kit on – never wanting to seem too keen. Then, of course, the question became how I was going to impress the coaches when everyone looked so much more experienced than me.

But for the nervous excitement and elation of every call-up there are as many crushing disappointments. Some are played out behind the scenes and some in the full glare of the international media. Second chances don’t always arrive, but what I’ve found astonishing about all the women I’ve talked to has been their persistence, determination and unflinching self-discipline to go back and try again, even when failure has been so agonizing. Athletes such as rower Katherine Grainger, who lost out on gold by the finest of margins but came back to make history, have great stories to tell. Confidence and toughness are always learned along the way, but I, like so many others, understand what it’s like to come back from the point of giving up.

That year for me was 2009. I had already been selected for the London 2012 Ambition Programme, which gave young hopefuls a taste of what an Olympics looked and felt like, but everyone knew that if you got picked it was almost guaranteed you were one of the top two in the talent coming through to be selected to go on to be in the London 2012 Olympic squad. Yet, for me, that didn’t happen. It being a home Olympics just rubbed salt into the wound. On that day in 2009 when I found out I hadn’t made the team, I spent the whole day buried under a duvet. The embarrassment was crippling. But it was a feeling I was to get used to. Not only did selection not happen for me then, it didn’t happen for me seven consecutive times throughout my career. And what most people don’t realize is that even in the face of failure, you still have to train with team members who are going to the Olympics or to other major championships. ‘Why am I here? I’m not even a reserve!’ I kept asking myself. By 2012 I knew I was good enough to be in the GB squad, so why couldn’t I get selected? After one gruelling training session I remember breaking down in uncontrollable tears.

What keeps sportswomen going back? It’s a question I’ve asked every woman, and the answers are different for every athlete. For example, long-distance runner Paula Radcliffe talks brilliantly about the need to keep racing, even when your body is screaming that you should give up. For me, it was pure stubbornness. I’d worked so hard that I wanted a shot at an Olympics. Every woman also has imprinted on her brain an image of an Olympic hero or heroine and mine was Kelly Holmes. Watching her eyes almost pop out of her head with shock at winning the dream double 800 and 1500 metres in Athens in 2004 was the one moment when I thought, ‘Wow. That’s exactly where I want to be.’ Those images really matter. For Fatima Whitbread it took twelve years to win her first major title in the 1970s. Nowadays, an athlete’s access to support and knowledge aided by technology means that that process is often speeded up. That said, it took me eight years to reach an Olympics. When I did, it was because I’d been through every emotion possible to believe that I still had what it took. After years of setbacks I also needed confirmation from my coach Danny Kerry. In one rather heated showdown he let me know: ‘Sam, I rate you as one of the best defenders. You are an integral part of this team,’ he said. It’s all I needed to know to propel me to the next level.

Yet periods of self-doubt can take athletes way off course. Skeleton champion Amy Williams and Rebecca Adlington open up in this book about how impostor syndrome plagued them during parts of their careers. Looking back on my own, I probably let it define me far more than it should have done. Yet it is all part of the roller coaster of elite competition. Even now I can suffer from agonizing self-doubt – when I stepped up to be the first woman captain of Question of Sport, or when I’m presenting live television programmes. It’s learning how to push through it that counts.

And when my big moment came, I grasped it with both hands. This time, my mum had the champagne on ice, confident I would be successful. I was but team sport is never about one person. It’s about everyone coming together to play at the top of their game. Yet that confidence and freedom that we played with and the Lionesses played with in Euro 2022 doesn’t happen in that one moment. It’s built over years.

Understanding your opponent is also key. Whether an athlete competes in an individual discipline or as part of a team, any psychological gains that can give you the advantage really matter. On the day we walked out on to that pitch for our final in Rio, a calmness and composure we had never felt before washed over every single woman in our team. We were there to do a job, and to win. But when we turned to face our Dutch rivals, they were banging their hockey sticks against the corrugated iron stadium wall. ‘They’re nervous,’ we thought. No doubt, it gave us the winning edge.

And winning does matter. I think it’s a word that British female athletes were maybe uncomfortable believing before London 2012, but a change in mindset has been pivotal to how women’s sport has grown in confidence and quality over the past decade. Before Rio 2016 we became unashamed winners – a culture shift that felt unnatural and difficult but which was vital to our success. And let’s face it, no one wants to watch a sport when the home team isn’t pushing their way through to semi-finals and finals, or sportswomen aren’t racing, throwing or skateboarding their way to podium places. Simply put: winners create winners.

Now I see that growing confidence everywhere I look in women’s sport. Whether it’s football, rugby, swimming or cycling. You name it, there’s a raft of world-beating talent out there who will inspire a generation into the next Olympics and Paralympics, just like the women in this book have inspired me. Certainly I hope my own daughter Molly, who is two years old at the time of writing, will never have to go through the serious hard graft that women have endured simply to be accepted in sport, if it’s a path she ever chooses.

Most of all, I see women becoming comfortable in their own skins playing sport, being competitive and wanting to reach the top of their game, whether that’s at school, at club level or at national or international competition. That more of us can be role models for others fills me with so much hope. I love sport. I love hearing the stories of women in sport, and I hope you will find these conversations as interesting and poignant, uplifting and joyful as I did having them.

Sam Quek, September 2023

CHAPTER 1

Making History

Paula Radcliffe MBE

LONG-DISTANCE RUNNER

‘I couldn’t run because I was crying. I couldn’t breathe properly, but I sat on a rock and thought, “I’m not carrying on like this. I think I can do it.”’

Fifty-one years ago, six women staged a sit-down protest at the start of the New York Marathon. It was 1972 and the first year that women had been allowed to race in the event. Conventional wisdom until that point was that long-distance running wasn’t just unfeminine but physically damaging to women, especially their reproductive health. Astonishing now that doctors claimed it could make a woman’s uterus fall out. When the US’s Amateur Athletic Union lifted its ban, it insisted on the women’s race beginning ten minutes ahead of the men’s. But for female runners fighting for equality, its ‘separate but equal’ ruling was unacceptable. When the starting gun sounded, ‘The Six Who Sat’ waited out the imposed head start cross-legged on the tarmac clutching handwritten banners before running with the men.

For me, born sixteen years later, it’s hard to imagine just how far the acceptance of women in sport has come. One of those six women, Nina Kuscsik, gave a flavour of that time in a recent interview recalling how if she ever trained on roads, police persistently pulled her over. ‘They always assumed I was running away from something. It didn’t cross their mind I could just be out running,’ she told reporters.

And it’s these steps that I also retrace with the legendary Paula Radcliffe when we speak. Her 2003 women’s marathon record – a blistering 2 hours, 15 minutes and 25 seconds – remained unbroken for sixteen years. Now most major city marathons have reverted to staggered starts, but Paula – who has fought a fair few of her own sporting battles – tells me how important that legacy was in paving the way.

Now there are separate starts to showcase the women’s event, and it’s how the women’s world record has evolved. It’s not to belittle women or get them out of the way before the proper race comes. It’s also to allow the media to show it properly and for people to watch it properly. It’s for a different reason and it’s a respectful reason.

What I hadn’t appreciated is just how much Paula’s own achievements are rooted in that same era – the 1970s and 1980s were the decades when women’s long-distance icons emerged. She reels off names like Grete Waitz, who in 1979 became the first woman to run the New York Marathon in under two and a half hours; Joan Benoit Samuelson, who in 1984 became the first female marathon Olympic champion; and 1980s former world record holder Ingrid Kristiansen – one of the most formidable runners of her generation whom Paula, aged just twelve, came within touching distance of.

One of my earliest memories was meeting my dad at the London Marathon. We were waiting for him at different points to give him his mini Mars bar and carton of orange juice. It was 1985 and I saw Ingrid Kristiansen setting the world record. Then, the women ran with the men so she was among the top 100 men, but it felt like she was really close to the front. I was in awe of how quick she was running and how well she was running. She was so iconic wearing her trademark white gloves with her short hair and she ran in men’s kit surrounded by TV cameras. Men ran with her just to be running with the leading female in the race. I remember thinking it was really cool that she was beating so many of them and she looked so strong. I was also captivated by the atmosphere of the marathon – it has an energy that if you are a runner you really pick up on. It inspired me.

But marathon runners like Paula aren’t made, they’re built. No one starts out fully formed or even necessarily wanting to run marathons. Instead athletes take incremental steps. Having been blessed with the perfect physique for her sport, Paula was first introduced to cross-country running, where many long-distance champions of both sexes have earned their stripes. A hearty breakfast of cheese and tomatoes on toast before getting filthy muddy are some of her fondest memories, but she also explains that cross-country taught her everything about her body’s strengths and weaknesses and the tactics of the long-distance race.

I was lucky that I found the sport that I loved early on. From the beginning I enjoyed how running made me feel. There were times when I didn’t want to train but I liked that battle between my body and my mind. And it’s probably why I drifted towards marathon in the end because that’s the ultimate challenge against your mind. I also felt really alive. When you’re running fast and the wind is in your hair and the trees are going by it feels like all your senses are on alert.

Cross-country was the way I got started and it’s brilliant. There’s no clock so time doesn’t matter, and you learn what type of course you run well on. You learn how to get a fast start which is really important. And it teaches you that fine line between the maximum effort you can sustain for the duration of the race and doing too much too soon. Too many athletes look at their heart rate, or look at their split times and that’s not relevant in cross-country. You need to be looking at the course and where you are putting your feet. It stood me in really good stead for the marathon because you have to red-line it. You have to know what your body is capable of because if you go too fast you can’t get over the finish. You run out of fuel.

I was also really lucky that when girls hit puberty their body shape can completely change, but mine didn’t. My hips didn’t grow massively. I didn’t get boobs – not great for a teenager, but great for a runner.

That said, Paula may never have realized her potential had it not been for the support of her parents, especially her dad who had been a keen runner at school. Sadly, Peter passed away in 2020 but the way Paula describes him, he sounds like a legend. Just before she was born he took up marathon running to lose weight after giving up smoking. Living in Cheshire, the Mersey Marathon became a prominent date on the Radcliffe family calendar, as did the London Marathon. Later, in Paula’s early teens when her parents relocated to Bedford, Peter spent time researching the best running club for Paula to join. That was Bedford and County Athletic Club where the coach Alex Stanton soon spotted her talent.