29,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

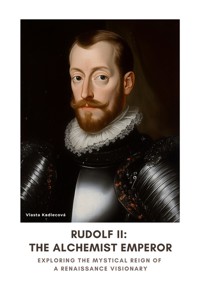

Step into the enigmatic world of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, whose reign marked a unique crossroads between mysticism, art, and emerging scientific thought. At his court in Prague, Rudolf gathered the brightest minds of his time—alchemists, astronomers, artists, and philosophers—fostering an intellectual environment that blended the empirical and the esoteric. This captivating exploration delves into Rudolf's lifelong obsession with alchemy and his pursuit of the elusive Philosopher’s Stone. From the grand ambitions of his alchemical laboratories to the celestial studies of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, Rudolf's court was a beacon of Renaissance curiosity and innovation. Yet, his reign was not without its challenges: political instability, religious strife, and personal eccentricities shaped his legacy as much as his patronage of the arts and sciences. Author Vlasta Kadlecová paints a vivid portrait of a monarch who sought to transcend the ordinary, capturing the essence of an era where boundaries between magic and science blurred. Rudolf II: The Alchemist Emperor is a compelling tale of ambition, transformation, and the enduring allure of the mysterious.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Vlasta Kadlecová

Rudolf II: The Alchemist Emperor

Exploring the Mystical Reign of a Renaissance Visionary

The Enigmatic Emperor: An Introduction to Rudolf II

The Rise to Power: Rudolf II's Early Life and Reign

Rudolf II, born on July 18, 1552, in Vienna, was a scion of the illustrious Habsburg lineage, destined to ascend the thrones of the Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia. His early life and subsequent rise to power provide a fascinating glimpse into the shaping of a monarch whose reign would be marked by both great ambition and turmoil.

From the outset, Rudolf's upbringing was a calculated affair, meticulously orchestrated to groom him for leadership. As the eldest son of Emperor Maximilian II and Maria of Spain, Rudolf was educated in an environment steeped in political intrigue and dynastic responsibility. His formative years were largely spent at the Spanish court, an experience that left an indelible mark on him. It was here that Rudolf was exposed to the strict formalities and staunch Catholicism of the Habsburg heritage under the watchful gaze of his uncle, King Philip II of Spain.

The time Rudolf spent in Spain was crucial, not just for the political education it provided but also for inculcating a mindset that would soon inform his reign. Surrounded by the grandeur of the Spanish court and the intellectual elite of Europe, Rudolf developed an early interest in the arts and sciences, influenced by the Renaissance spirit that permeated the age. This period of his life is noted by historians such as Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann who states, “His early exposure to cultural pursuits laid the groundwork for Rudolf’s later patronage of the arts.”

Upon his return to Central Europe, Rudolf was increasingly engaged in the affairs of the realm, assuming the roles and responsibilities expected of a future monarch. His official investiture as King of Hungary in 1572 marked the beginning of his political career, followed by his coronation as King of Bohemia in 1575, and finally, in 1576, as Holy Roman Emperor, succeeding his father, Maximilian II.

Rudolf’s rise to power during this period coincided with significant challenges. The Habsburg territories were a complex mosaic of various ethnic groups, languages, and religious beliefs. Maintaining cohesion within such a sprawling empire was an arduous task, compounded by the mounting tensions of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. Rudolf’s reign would consequently be characterized by his constant struggle to maintain religious and political equilibrium amidst growing dissent.

At the heart of Rudolf's early reign was his decision to relocate the imperial court from Vienna to Prague in 1583. This move not only marked a geographical shift but also symbolized a broader intellectual and cultural transformation within the empire. Prague, under Rudolf's patronage, became a vibrant center of art and science, attracting scholars, artists, and alchemists from across Europe, eager to contribute to Rudolf’s vision of a cosmopolitan court.

As a ruler, Rudolf II was an enigmatic figure, embodying the contradictions of the era. His keen interest in the esoteric arts and alchemy, alongside his commitment to fostering an environment of scientific inquiry, set him apart from his contemporaries. His reign, though punctuated by political instability and personal struggles, left an enduring legacy on the cultural and scientific landscape of Renaissance Europe.

Thus, the early years of Rudolf II’s life and reign paint a picture of a man both shaped by his dynastic obligations and driven by a personal quest for knowledge and discovery. His trajectory from a young Habsburg prince to a ruler of an empire reflects the broader narrative of late Renaissance Europe—a period marked by burgeoning intellectual curiosity amidst the backdrop of political and religious upheaval. This duality in Rudolf's early life would foreshadow the unique and complex nature of his rule, laying the groundwork for his insatiable pursuit of the philosopher’s stone.

The Habsburg Legacy: Context and Challenges

The Habsburg dynasty, to which Rudolf II belonged, was one of the most influential royal families in Europe. Their vast empire spanned numerous territories, comprising present-day Austria, Hungary, Spain, and the Netherlands, among others. The family's influence reached its zenith during the reign of Charles V, Rudolf's grandfather, who famously declared, "In my realm, the sun never sets." Such immense power came with both privileges and burdens that would have profound implications for Rudolf II’s rule.

Rudolf II was born into a family with a legacy of diplomacy, warfare, and complex dynastic politics. The Habsburgs were celebrated for their strategic marriages, which expanded their influence across the continent without the necessity of warfare. However, this strategy also entangled the dynasty in the religious wars and conflicts that plagued Europe during the 16th century. By the time Rudolf II ascended the throne in 1576, he was inheriting an empire fraught with religious divisions, particularly between Catholics and Protestants, which were exacerbated by his own Catholic inclinations.

The Treaty of Augsburg in 1555 sought to quell the religious discord within the empire by allowing rulers to choose either Catholicism or Lutheranism as the official faith of their realm. This provision, often summarized in the phrase cuius regio, eius religio—"whose realm, his religion"—provided temporary respite but left deep-seated tensions intact. As Rudolf II assumed the throne, these embers were ready to ignite, demanding tactical astuteness and diplomatic finesse from the new emperor.

Moreover, Rudolf inherited a complex web of financial responsibilities. The continuity of war and the costs of maintaining a sprawling empire had placed immense pressure on the Habsburg treasury. The economic challenges were compounded by the costly patronage of the arts and sciences, for which Rudolf II became particularly famous. Rudolf’s predecessors had cultivated powerful feudal relationships and alliances that came with obligations of land grants and military support, further straining the imperial coffers. The need for fiscal prudence would become a recurring theme throughout Rudolf’s reign, influencing many of his decisions.

Aside from political and economic constraints, Rudolf faced the vast administrative challenge of governing a multicultural and multi-lingual empire. The Habsburg dominions were not a single homogeneous entity but a tapestry of different ethnic groups, languages, and customs. Each territory presented its unique customs, laws, and expectations, and unifying these diverse lands under a single administration proved to be an ongoing challenge. This mosaic of cultures required an adept handling of regional biases and diplomacy, essential qualities for maintaining cohesion within the realm.

Rudolf II's centralization of the imperial court at Prague can be perceived as both a strategic retreat from the heartland of Habsburg power in Vienna and a calculated move to exert his influence over the diverse territories of his realm. By establishing Prague as an imperial capital, Rudolf sought to merge the cultural and intellectual currents of Europe’s center with the legacy of Habsburg might. This decision reflected his ambition to unify the empire’s multiplicity within the framework of Renaissance intellectualism and served as a backdrop for his personal obsessions, particularly alchemy and the arts.

Yet, despite the numerous challenges, the Habsburg legacy endowed Rudolf with substantial leverage. The dynasty's deep-seated connections provided him with an intellectual and political network of allies and rivals. Moreover, the considerable prestige associated with the Habsburg name offered Rudolf opportunities to pursue his own interests—whether through patronage of the arts or the esoteric pursuits that characterized his court—in ways that might have been inaccessible to a less illustrious ruler.

In summary, the Habsburg legacy presented Rudolf II with formidable challenges and unparalleled opportunities. His reign can be seen as a balancing act between maintaining the stability of an extensive, multicultural empire and indulging in the intellectual and artistic pursuits that a ruler of his stature could afford. Understanding these complexities provides crucial insights into the motivations and psyche of this enigmatic monarch, setting the stage for the subsequent chapters that delve deeper into his life and the eccentric court he cultivated in Prague.

The Court at Prague: A Hub of Knowledge and Mystery

The reign of Emperor Rudolf II, from 1576 to 1612, stands out as a period bursting with intellectual fervor, intricate courtly intrigue, and an insatiable quest for the mysteries of the natural world. This epoch, which witnessed the convergence of science, exploration, art, and magic, found a fitting epicenter in Rudolf’s court at Prague. The city, poised on the crossroads of Europe, became a magnet for the curious and the learned, the mystics and the rationalists. Under Rudolf’s patronage, Prague transcended its political role to embody a vibrant nerve center of knowledge and esoteric pursuits.

Rudolf II, a member of the Habsburg dynasty, reshaped the imperial court at Prague Castle into a hub for the greatest minds of the day. His insistent curiosity, coupled with a reputation for eccentricity, crafted an environment where discussions ranged from alchemical experiments to philosophical debates. The court teemed with scholars, alchemists, artists, and astronomers, each drawn by the emperor’s famed patronage and the chance to explore uncharted intellectual territories.

The City as a Confluence of Cultures and Ideas

Prague's strategic location made it an ideological melting pot, hosting Jewish, Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox practitioners, leading to a rich tapestry of cultural and religious dialogues. Rudolf's court, in particular, mirrored this diversity. Seventeenth-century Prague was not just a melting pot of cultures but an intellectual crucible where ideas were tested and refined. The city’s university attracted students and teachers from across the continent, eager to tap into this vibrant environment. The court housed libraries that brimmed with texts from across the known world, making it a treasure trove for researchers.

One notable resident was the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose precise measurements of the stars were integral to the later works of Johannes Kepler. Brahe’s presence symbolized the union of rigorous scientific inquiry with the emerging world of Renaissance thought, a blending of empiricism and philosophy characteristic of Rudolf’s Prague. The writings of these scholars, such as Brahe’s meticulous 'De Mundi Aetherei Recentioribus Phaenomenis Liber Secundus', served as bedrocks for future astronomical studies.

Alchemy and the Philosophical Underpinnings of the Court

Alchemy, at the heart of Rudolf’s interests, was more than the pursuit of gold-making. It represented a philosophical and spiritual journey, intertwined with the neoplatonic and hermetic traditions that Renaissance thinkers revered. The alchemical practices espoused at the court aimed at transforming not only materials but also the human soul. Rudolf saw in alchemy the potential for a cosmic balance, a way to grasp the universe's secrets, best illustrated in manuscripts like the 'Rosarium Philosophorum' which explored these transformative processes.

The Emperor attracted myriad scholars who delved deeply into these mysteries. Figures such as Edward Kelley and John Dee were frequents at his court, forming part of a secretive and often enigmatic retinue. Their works, whether legitimate science or pure quackery, were encouraged and funded, leading to a bloom of alchemical literature and experimentation that lent Prague a mystical aura.

Artistic Achievements at the Court

The same spirit of exploration extended to the arts. Rudolf was a voracious collector, amassing works that spanned styles and media. His collection provided a fertile ground for artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whose intricate and allegorical portraits became emblematic of Rudolf’s court. These artworks were not mere decorations but visual embodiments of the esoteric themes that preoccupied the Emperor, blending the seen and unseen in a tangible form.

Through the patronage of such diverse talents, Rudolf’s court mirrored his own intellectual pursuits. It served not only as a place of governance and diplomacy but also as a laboratory and museum, nurturing the interwoven paths of science, magic, and art. This courtly world, with its complex amalgamation of disciplines, played a vital role in seeding what would become a flowering of scientific thought and artistic achievement in subsequent centuries.

The Legacy of Knowledge and Mystery

The legacy of Rudolf II’s court endures as a testament to an era where the boundaries of knowledge were ever-expanding and perpetually challenged. The intellectual climate at Prague gave impetus to developments that would usher in the scientific worldview of the Enlightenment. While Rudolf himself remains an enigmatic figure, his court's contributions to the arts and sciences are indisputable.

Today, Prague stands not only as a city of historical significance but also as a symbol of the rich interplay between the known and the mysterious that defined the late Renaissance. The achievements fostered under Rudolf II's auspices played a pivotal role in setting the stage for subsequent intellectual revolutions, making the Emperor's legacy indelible in the annals of history.

The Intellectual Climate of the Late Renaissance

The late Renaissance was an era marked by dynamic intellectual transformations and an unparalleled quest for knowledge, setting the stage for the profound amalgamation of science, philosophy, art, and mysticism. Situated in the midst of this transformative period was the court of Emperor Rudolf II, whose reign from 1576 to 1612 became emblematic of the age’s intellectual prowess. This epoch was not merely an extension of the Renaissance but a distinct phase that thrived on the intersection of tradition and innovation, creating a fertile ground for the acceleration of human understanding.

The intellectual fervor of the late Renaissance was characterized by a loosening of medieval scholastic constraints and a burgeoning interest in empirical observation and scientific inquiry. This was a period where the boundaries of conventional academe were increasingly challenged. The Renaissance humanists sought to revive classical knowledge, but it was during the late Renaissance that this revival intersected with the emerging scientific methods, leading to what many historians describe as the precursor to the modern scientific revolution. In this environment of intellectual upheaval, Rudolf II's court in Prague became a convergence point for thinkers, scientists, and alchemists from all over Europe.

The city of Prague, under Rudolf’s patronage, transformed into a vibrant hub where the arts and sciences flourished in tandem. Rudolf’s fascination with the mysterious and the arcane drew numerous scholars, artists, and alchemists to his court. These thinkers were compelled by the spirit of inquiry that defined the late Renaissance. As noted by historian Peter Marshall, "Rudolf's court was intended as a microcosm of the new cosmopolitan world that he wished the Habsburgs to rule, populated by the best and most fascinating individuals Europe could offer" (Marshall, 2006).

During this period, the dichotomy between science and mysticism was not as clear-cut as it is today. Alchemy, astrology, and astronomy were bedfellows, sharing the aim of uncovering the hidden truths of the universe. The intellectual climate was one of ambiguity, where faith intertwined with reason. Alchemists, who sought not just the transmutation of metals but also the metaphysical purities of spiritual enlightenment, were entwined with the scholars who pursued empirical science. Just as John Dee, an influential figure in Rudolf's court, remarked, "Mathematics is the door and key to the sciences" (Dee, 1591), summing up the Renaissance conviction that all knowledge was interconnected.

The late Renaissance was also an era deeply invested in the dissemination of knowledge, largely facilitated by the advent of the printing press. The widespread distribution of printed works allowed for a greater democratization of knowledge and fostered a vibrant intellectual exchange across borders. The works of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo began to circulate, challenging traditional cosmological understanding and inciting debates that would ripple through the intellectual circles of Europe.

Rudolf II’s court was an epicenter of this intellectual cross-pollination. Scholars and mystics alike were given the rare opportunity to work under the Emperor's generous patronage. Art and science were closely linked, evidenced by artists like Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whose works epitomized the fusion of human anatomy with botanical forms, reflective of the period's fascination with natural sciences. The court's library burgeoned with texts covering a myriad of subjects, from ancient Greek philosophies to contemporary scientific treatises. Rudolf’s own eclectic collection included numerous esoteric and alchemical manuscripts, embodying the intellectual curiosity that was characteristic of the late Renaissance.

The late Renaissance, therefore, was not simply a bridge between the medieval past and the modern future but rather an era of intellectual ambition and cultural richness on its own terms. It synthesized diverse threads of intellectual pursuit into a unique tapestry, one where Rudolf II became a pivotal figure. Under his aegis, Prague became a crucible for ideas that would ultimately shape the course of European thought and lead humanity into new frontiers of discovery. The intellectual climate of this period is a testament to the enduring legacy of an age where epistemological boundaries were meant to be challenged, and Rudolf II stood at its very heart, championing the conquest of the unknown.

Rudolf II and the Patronage of Arts and Sciences

During the late Renaissance, an era marked by profound intellectual transition and cultural effervescence, Emperor Rudolf II emerged as a singular patron of the arts and sciences. His reign, a medley of grand pursuits and enigmatic motivations, stands as a testament to the transformative power of patronage in shaping the intellectual landscape of Europe. Rudolf's unwavering support for scholars, artists, and alchemists alike significantly influenced the trajectory of scientific and artistic endeavors during his time, earning him a distinctive place in the annals of history.

The court of Rudolf II in Prague became a vibrant nexus for creativity and inquiry, attracting a diverse array of intellectual luminaries. Not confined by the rigid categories of art or science, the environment he cultivated was one where boundaries were continually pushed and disciplines intermixed freely. This symbiotic relationship between art and science was emblematic of the Renaissance spirit, but nowhere was it more fervently embraced than in Rudolf's court.

One of the pillars of Rudolf's patronage was his support for astronomical advancements, epitomized by his relationship with the renowned astronomer Tycho Brahe. Rudolf invited Brahe to his court in 1599, providing him with the resources needed to refine astronomical instruments and enhance the accuracy of stellar observations. This collaboration laid the groundwork for the eventual work of Johannes Kepler, Brahe’s successor, whose groundbreaking laws of planetary motion emerged from the data meticulously gathered under Rudolf's auspices.

Beyond astronomy, Rudolf's fascination with collecting played a pivotal role in advancing the arts. His extensive collection of art and curiosities, known as the Kunstkammer, was one of the most comprehensive of the time, blending natural curiosities with intricate works of art. This encyclopedic collection was not only a symbol of prestige but also a source of inspiration and study for artists and scientists alike, offering a microcosm of the Renaissance's interdisciplinary approach to knowledge.

Alchemical experimentation featured prominently among Rudolf's interests. His court hosted an array of alchemists who sought both the metaphysical transformation proposed by the Philosopher’s Stone and the tangible advancements in metallurgy and chemistry that early alchemical practices promised. Figures like Michael Maier and Edward Kelley thrived under Rudolf's patronage, navigating the delicate balance between the mystical and the empirical, which characterized much of the alchemical pursuit during this period. Though the Philosopher’s Stone remained elusive, these endeavors contributed to a burgeoning understanding of substances that laid foundational insights for modern chemistry.

Rudolf’s support of the visual arts also left an indelible mark. Artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, known for his imaginative portrait busts composed of fruits, vegetables, and other objects, received commissions that reflected the emperor's penchant for both the whimsical and the intellectually stimulating. The court became a vibrant space where artistic innovation flourished, enriched by the cross-pollination of ideas from various disciplines.

Furthermore, Rudolf II’s patronage extended to innovations in medical and anatomical studies. The emperor's encouragement of figures like the anatomist Johannes Jessenius fostered progressive approaches to understanding the human body, which were crucial stepping stones toward modern anatomical science.

While Rudolf's indulgence in the arts and sciences was at times driven by personal idiosyncrasies and an intense quest for the extraordinary, the resulting cultural and intellectual milieu at the Prague court was undeniably influential. His reign came to symbolize a pivotal moment wherein the nurturance of creativity and knowledge not only celebrated the intellectual heritage of the Renaissance but also paved new pathways for the European Enlightenment.

In practical terms, Rudolf II’s impact as a patron was profound in that it established Prague as a crucial center of knowledge and creativity. While his support often drew criticism from more conservative elements of his era, the lasting contributions derived from his patronage underscore the importance of fostering environments where inquiry and imagination can thrive unchecked by convention. In this way, Rudolf II’s seemingly eccentric interests ultimately contributed to a legacy of intellectual and cultural richness that echoed far beyond his reign.

The Emperor’s Obsession: Alchemy and the Quest for the Philosopher's Stone

Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1576 until 1612, is often portrayed through the lens of his profound fascination with the mystical and the arcane. Among his many interests, alchemy stood out, embodying both a personal obsession and a broader symbolic pursuit of knowledge that intertwined with his reign. Rudolf's quest for the Philosopher's Stone—a legendary substance purported to transmute base metals into gold and bestow immortality—exemplified the intriguing blend of science, mysticism, and ambition that characterized his court.

Rudolf's enthrallment with alchemy can be attributed to his complex psyche, which sought to reconcile his roles as a ruler with his aspirations as an enlightened patron of the arts and sciences. His court in Prague became a haven for alchemists, scholars, mystics, and artists, a sanctuary where ideas could be exchanged freely across disciplines. The pursuit of the Philosopher's Stone was more than mere superstition; it was a genuine intellectual endeavor that reflected the Renaissance quest for understanding the universe's hidden truths.

Central to Rudolf’s fascination with alchemy was the allure of unlimited potential. The Philosopher's Stone, with its associated alchemical and spiritual promises, symbolized the ultimate mastery over nature—a power that must have been irresistibly alluring for an emperor striving to maintain control over a fragmented empire plagued by religious and political strife. Rudolf held firm beliefs that alchemy could uncover secrets that transcended conventional boundaries of human knowledge. In the shadow of tumultuous times, alchemy represented a beacon of hope, offering solutions not only to enrich the empire materially but also spiritually rejuvenate a civilization seeking meaning beyond dogmatic beliefs.

The emperor’s patronage drew some of the most notable alchemical figures of the era to Prague, including John Dee, Edward Kelley, Michael Maier, and Heinrich Khunrath. Each brought their unique interpretations and practices of alchemy, contributing to what became known as the 'Golden Age of Alchemy,' uniquely marked by Rudolf's eclectic interests. Rudolf's court thus served as an epicenter where the esoteric teachings of these alchemists could flourish. It was a place where practical experimentation intertwined with metaphysical exploration.

Rudolf’s investments in alchemy went beyond the mere accumulation of texts and trinkets; he commissioned laboratories and filled his castle with intricate apparatus. These acts underscored his dedication and his desire to see alchemy not just as mystical incantations, but as a legitimate form of inquiry akin to the burgeoning scientific methods of the time. As historian Bruce T. Moran notes, "Rudolf worked to position the art of alchemy as a branch of learning that could hold its own with the emerging fields of scientific study."

Despite the ambitious nature of his quests, Rudolf's alchemical ventures were not without criticism or controversy. Detractors often perceived his interests as reckless distractions from pressing political and administrative duties. His relentless pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone reflected his detachment and disengagement from matters of state, contributing to his reputation as an ineffectual monarch. Moreover, the financial expenses required to sustain such an extensive assembly of alchemical pursuits strained the imperial treasury, exacerbating tensions within the court and beyond.

Nevertheless, Rudolf's engagement with alchemy left an indelible mark on the history of science and culture. By blurring the lines between scientific study and mystical pursuit, he helped lay the groundwork for future generations to integrate scientific rigor with philosophical inquiry. This convergence paved the way for the eventual transition from alchemy to chemistry. In many ways, Rudolf’s court anticipated the Enlightenment’s emphasis on empirical evidence and reason, even as it was immersed in the enigmatic and the arcane.

Rudolf II’s obsession with alchemy epitomizes the complex interplay of power, knowledge, and mystery that defined his reign. His persistent quest for the Philosopher’s Stone, while ultimately unfulfilled in its literal sense, catalyzed an era of intellectual enthusiasm and innovative thought that echoed far beyond the labs and libraries of Prague. Indeed, his legacy as an alchemical emperor has endured, continuing to captivate historians, scientists, and alchemists alike with the rich tapestry of endeavors, aspirations, and enigmas that his life represents.

Mystics and Scholars: Influential Figures in Rudolf’s Court

Rudolf II, the reclusive Habsburg emperor who ruled over the Holy Roman Empire from 1576 to 1612, cultivated a court that was a crucible of intellectual and esoteric pursuits. His rule stands out not only for the political and religious tumult of his time but also for his insatiable interest in the mystical and the scholarly worlds, drawing to him some of the most intriguing minds of the Renaissance. Under his aegis, Prague became a melting pot of mystics, scholars, artists, and alchemists—a distinctive intellectual climate that profoundly influenced the era's cultural landscape.

One of the emperor’s most significant influences was John Dee, the illustrious mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and advisor to Queen Elizabeth I of England. Dee, along with his companion Edward Kelley, traveled to the court of Rudolf II, bringing with them the promise of uncovering secrets of the universe and, notably, the elusive Philosopher's Stone. Although Dee’s ambitions often bordered the magical and the scientific, his extensive knowledge in various fields earned him a place in the court’s inner circles. His interactions with Rudolf exemplified the period's blurred lines between science and mysticism, as both men pursued the alchemical transformation of both matter and spirit.

Edward Kelley, Dee’s enigmatic partner, deserves mention not just for his role as an alchemist but for the controversies that followed him. Known for his supposed ability to communicate with angels, Kelley’s time at Rudolf's court was marked by a blend of promise and deception. While some regarded him as a charlatan, others saw him as a genuine seeker of hidden truths. Rudolf’s fascination with Kelley perhaps illustrates the emperor’s own yearning to transcend earthly limitations and unlock the divine mysteries of creation.

The court was also home to the brilliant Tycho Brahe, a Danish nobleman famed for his precise astronomical observations. Brahe’s presence at Prague is a testament to Rudolf’s commitment to advancing scientific thought. Appointed as the imperial astronomer, Brahe brought with him decades of research and a dedication to empirical observation. His work laid the groundwork for future scientific breakthroughs, serving as a bridge between the mystical aspirations of the court and the burgeoning field of modern science.