5,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

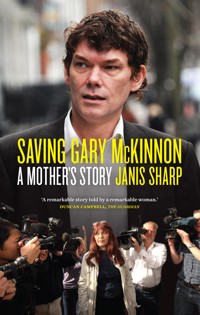

The ordinary lives of Gary McKinnon and his mother Janis changed dramatically one morning in 2002 when police interviewed Gary about hacking into US government computers. Three years later, on 7 June 2005, he was arrested. Extradition seemed certain and so, fearing that Gary would take his own life rather than be taken away, Janis began her extraordinary battle. Facing up to sixty years' incarceration, Gary was vilified by the authorities, who described his actions as 'the biggest military computer hack of all time'. The truth was rather less dramatic - Gary was searching for signs of UFOs. When he discovered that thousands of NASA and Pentagon computers had no passwords or firewalls he started to leave notes warning that their security was deeply flawed. It was only in 2008 after a TV interview that an expert in autism phoned Gary's solicitors and said he was sure that Gary was suffering from Asperger's syndrome. The stakes were now even higher. The US judiciary had all the might of the world's greatest power. But it had not reckoned on Gary's mother. This is the story of how one woman squared up not only to the Pentagon but also to the British judicial and political systems. It is a book about a mother who took on the world and won.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

To Wilson, my husband, the love of my life, whose love, care, optimism and humour kept me going through the darkest of times. Without him life would have been infinitely harder, much less interesting and much less fun.

To my son Gary, a talented and extraordinary man who I love dearly and am proud to call my son, and to Lucy, whose light and laughter shone into his life.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY JULIE CHRISTIE

When the news broke that a young man from north London called Gary McKinnon was to be extradited to the United States for hacking into computers there and leaving behind him some rude remarks, I was as puzzled as anyone. What had he done that could not be dealt with by the British courts? Why was it so serious that years after the hacking the American authorities, all the way up to their Attorney General, were still pursuing him?

It gradually became apparent that the authorities were hunting him for a crime that, as far as I know, is still not on the statute books: causing the United States government deep embarrassment. In the meantime Gary, to his bewilderment, had suddenly to fight to remain in Britain and avoid the possibility of being locked up in an American penitentiary, labelled a national security threat. And anyone who has followed what has been happening in Guantanamo Bay over the last decade will know that once ‘national security’ is involved in the United States the chances of a fair trial – or even a trial at all – become minimal.

It was Gary’s mother Janis Sharp who led the ultimately triumphant battle to halt the extradition. Without her courage and determination, Gary would undoubtedly now be behind bars – or not with us at all. In this book, Janis tells us about Gary’s childhood and his curiosity about UFOs that led to his eventual hacking of the NASA computers, how she first learned of his arrest, how he came to be diagnosed as suffering from Asperger’s, and how the efforts to save him slowly built into one of the most admired – and successful – campaigns for justice that many of us can remember.

The book paints a much fuller picture of Gary and of Janis than we have ever had before. It catalogues the highs and lows of the rollercoaster ride to halt the extradition. It also acts as a fine example of how to mount a campaign when all the odds seem stacked against you, and provides a fascinating insight into how politics, the law and the media work in Britain.

Janis Sharp is a remarkable woman. That someone should dare to take on the mighty authoritarian institutions that control our lives, with no prior experience of doing so, should be an inspiration to us all. As injustices grow in the wake of the ‘war on terror’, this book is essential reading, not only as a political thriller and a personal story, but also as an eye-opener to the way our freedoms can be threatened. Bravo, Janis!

Julie Christie

June 2013

CHAPTER 1

OUT OF THE BLUE

How did this happen? I mean, out of all the people in the world, why us?

It was 19 March 2002 when my son Gary McKinnon was arrested by the Hi-Tech Crime Unit. Ironically, I had said to my husband Wilson, Gary’s stepdad, just months before: ‘Isn’t it amazing that Gary has reached the age of thirty-five without getting into heavy drugs or into trouble of any kind?’

I should have known then – once you start patting yourself on the back something happens to make you wish you had kept quiet. Maybe we had tempted fate into deciding we’d had life too easy.

Just hours before the phone call from Gary I was snuggled up in bed next to Wilson, thinking I could happily stay there forever.

It had been the same as any other morning – being woken by our dogs barking and Wilson bounding down the stairs to let them out.

Drinking tea and gazing through the patio window as the sun filtered through, I thought how much I loved life, loved watching the dogs running around in the garden, the fish swimming in the pond and the birds eating the berries from the tree. I was blissfully unaware that these moments of peace were about to be snatched away.

‘Wilson! Let’s take the dogs out.’

‘OK, I won’t be a minute,’ said Wilson as he headed for the bathroom.

I switched on my computer, knowing that Wilson’s minute means he disappears into a black hole and emerges half an hour later, book in hand, lost in the story he’s been reading.

I’m still in awe of how via the internet I can access the most intricate details of virtually any subject from across the globe. I’ve always been good at absorbing information; having the library of the world at my fingertips is something I never take for granted.

‘I’m ready, dogs out,’ called Wilson, standing in the doorway all wrapped up and looking like a Viking Santa Claus as he absent-mindedly stroked his white beard.

‘Have you got the keys and the phone?’

‘I have,’ said Wilson, still lost in thought.

‘Then let’s go.’

Dogs in tow, we walked through the trees, their branches held out like arms for woodland creatures to perch on and to shelter in, breathing peace into the atmosphere of nature’s cathedral.

As Wilson told me in detail about the story he’d been reading, we were transported into another world, as our hounds ran like deer through the woods.

• • •

Arriving home we heard the phone ring, missed it. It rang again. It was Gary.

‘Mum.’

‘Hi Gary.’

‘Mum, don’t get upset. I’ve got something to tell you, but don’t worry.’

‘I’m worried, tell me!’

‘I was arrested.’

‘Arrested? What do you mean, arrested? Why would you be arrested?’

‘For hacking into NASA … and the Pentagon.’

‘What! NASA? The Pentagon? How could you have hacked into the Pentagon?’

I was gripping the phone so tightly the blood was draining from my hands as panic came in waves. I was wishing he would laugh and say he was joking, but Gary tells the truth – that’s just the way he is.

The sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach was pulling me deeper and deeper and I instinctively felt this was way more serious than Gary realised.

‘I was searching for information on UFOs. Don’t worry, Mum. The police from the Hi-Tech Crime Unit are really nice; they’re computer guys just like me.’

Oh Gary, they’re not like you, and you need a lawyer.

‘They told me they’d been monitoring my computer for months and as I hadn’t done any damage I was looking at six months’ community service. It’s OK.’

I wanted to ask him how he could have been so stupid. I wanted to shake him and wake him up, but most of all I wanted to wrap him up in my arms to protect him: he was my son and an innocent to the core.

That’s the thing about being a parent: your child is your child no matter what age they are. Their troubles are your troubles and you somehow find the strength to move mountains to protect them.

‘I’ll get you a lawyer, Gary.’

‘I don’t need one; I’ve told the Hi-Tech Crime Unit everything and they said they might give me a job after all this, as they need people like me.’

Oh Gary! Gary, this is America we’re dealing with, this is Goliath.

I wanted to scream and tear my hair out at his naivety.

‘I’ve always told you, if you were ever in trouble to ring me and I’d get you a lawyer. Why didn’t you?’

‘I didn’t want to worry you.’

‘You have worried me! Where are you?’

‘I’m on my way home; they said they’ll let me know when they want to speak to me again. I have to go.’

A wave of relief swept over me knowing that at least he was free: they didn’t have him, he wasn’t a prisoner, he was free.

It seemed ironic, as when Gary was younger he wanted to work for the police and I had talked him out of it. I was afraid of the violence in London and that people he knew might distance themselves from him, the way people often tend to do with the police. Now he had been arrested I started to question every bit of advice I’d ever given him. Maybe if I’d encouraged him to join the police he wouldn’t be in this position now and would be working for the Hi-Tech Crime Unit instead of being arrested by them.

‘Maybe’ this, ‘maybe’ that, could have, should have, if only…

It’s funny how when things go wrong we tend to keep going over the past, trying to work out how we could have avoided being in the place we’re in now, even though we know it’s too late to change things.

We used to say Gary was thirty going on thirteen. That annoyed him, but he’s always been naive and young for his age, although clearly intelligent.

‘What are we going to do, Wilson?’

‘There’s nothing we can do, we’ll have to wait and see what happens.’

‘We can’t wait! This is NASA and the Pentagon we’re talking about. How could Gary have hacked into the Pentagon? It’s mad. Apart from anything else, surely Pentagon security has to be the best in the world?’

‘You’re pacing, Janis.’

‘I never pace.’

‘You do now.’

‘Maybe Gary should go and live with his dad in Scotland for a while and they’ll forget about it. I want him to be somewhere safe.’

‘He can’t, he’s on bail.’

‘I don’t like this. If he got six months’ community service that would be fine but I can’t see it somehow.’

Wilson was calm. Wilson is always calm and I was glad of it at that moment as I had gone straight into panic mode. I wished my mum was still here – she always had good instincts and would have known what to do.

CHAPTER 2

LIFE BEFORE TECHNOLOGY

My mum, Mary May Macleod, was the heart of our family; and like the sun our lives revolved around her. Her eyes mirrored her soul. She had the most wonderful imagination and sense of playfulness and filled the house with music and laughter. She was half Irish and amazingly used to dream about our family’s babies before they were born and before anyone realised they were pregnant.

It’s said that many Celts have the gift of second sight and I know that in our family prophetic dreams are an accepted part of our lives. However, my dad, an engineer, had a practical approach to life and a fear of anything described as supernatural, so we were never allowed to speak about anything out of the norm when he was in earshot.

My dad was Donald John Macleod from Stornoway, the main town on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. His family lived on a croft in an area that survived by self-sufficiency. They spun their own wool, fished in the sea, grew their own food and kept their own animals to provide a source of cheese, milk and eggs. My dad spoke only Gaelic when he first arrived in the big city of Glasgow in his teens. He was a proud, hardworking man who, in true Highland fashion, would not drink a drop of alcohol on a Sunday. He enjoyed cooking us all a healthy breakfast, and tried to encourage us to eat things like kippers, which to a child were pretty unappetising.

My dad was fascinated by the moon landing and had a passion for astronomy, taking us all out onto the veranda one night to view the passage of a comet, which was a magical moment for us.

My mum didn’t know she was pregnant with me as her periods hadn’t stopped, but she then had what the doctors thought was a miscarriage. They said no baby could have survived as she had lost everything, but unbeknown to them, there was a determined little girl still in there clinging on for dear life.

I was born dead, my mum had haemorrhaged and her life was in immediate danger. She was adamant that the doctors should attend to me first but they had decided it was too late for me and were working on my mum as a priority. Hearing my mum’s pleas for her baby’s life, a young nurse held me in her arms and refused to give up as she persistently tried to breathe life into my rapidly cooling body until finally I gasped for air. The last thing my mum heard before slipping into unconsciousness was the sound of her baby, crying. She said I was meant to be.

• • •

I was born in Glasgow as Janis Thomasina Macleod, the youngest of three children. We lived in a place called Gilshochill, not far from Maryhill.

One of the earliest and most haunting memories of my childhood was standing up in a metal cot in a children’s home, holding onto the sides and crying and crying for my mum. Even now, just touching on the memory, tears well up, blurring the letters on the page.

My dad came to visit me in a children’s home he had been forced to put me into temporarily when my mum was seriously ill in hospital and there was no one at home to look after me. He had my seven-year-old sister Lorna in tow.

My memory of this is vivid. I could hear the nurse’s voice saying, ‘She won’t eat, and just stands in her cot looking at the door and won’t stop crying.’

‘Take her home, Daddy,’ Lorna said pleadingly.

‘I can’t, I’ve got to go to work.’

‘I’ll look after her, Daddy.’

‘You’re too young, and you’ve got school.’

‘But Mrs Clarke from upstairs will help me. Please, Dad. She needs to come home, we can’t leave her here.’

My sister Lorna was fighting for me; she knew I was scared and she wouldn’t give up until she had persuaded my dad, who thankfully relented and took me home.

The next memory I have of that time was when, months later, my mum, who had been seriously ill, came back home from the hospital and was standing in the darkened hall of our old ground-floor tenement flat in Glasgow. Lorna was holding me in her arms with her pigtails brushing my cheek and I remember I felt angry at my mum because she had left me and I clung to Lorna. Then I heard my mum’s voice, warm and familiar but filled with sadness, saying, ‘She doesn’t remember me.’

I reached out, to be lifted up by my mum and held in the comfort of her arms. Home was home again and at the age of one I was back with my mum where I belonged.

Who knows how I can remember that far back, but I can. Maybe it’s the memory of this traumatic childhood experience of separation from my family that led to me feeling even in adulthood that I had to be in control of certain situations.

I was incredibly attached to my mum; she was so different from anyone I’ve ever known. When my sister, brother and I were little she used to spread thick polish on the floor and then tie rags onto our feet and we would slide around on the floor, laughing and singing and falling over and getting up again and sliding around some more until we had polished the floor to a high shine while having the most amazing time. She was brilliant at inventing the most ingenious ways of doing things.

In those days television was so new that it was rare for anyone in Scotland to have one and as children we mostly played outdoors. Some of our play was quite entrepreneurial. The older children would chop up wood while we younger ones tied the wood up in bunches, selling it door-to-door to get money to buy sweets or toys.

We occasionally went into the local chapel when it was empty and, regardless of anyone’s religion, we would light candles and then ask God if we could take a few of the candles for our homemade den and some of the holy water in a small container. God always said yes, of course, and the few times the priest saw us he would tell us off gently, with a smile and sometimes with a wink. The doors of churches and chapels were always left open in those days.

The older children would boast to friends and neighbours that the holy water had spiritual powers, which we wholeheartedly believed. Some children would offer us sweets or sometimes, more appropriately, angel scraps in return for a few drops of the holy water with the magical powers.

Scraps were essentially like Victorian paintings of cherubs, children and animals printed on thin pieces of shiny paper that we’d keep in pages of books and then swap or trade with each other from our beloved den.

When it rained we played in our den and when there was thunder and lightning and the atmosphere seemed sinister, we’d sit inside our den with the candles lit, or in the enclosed stairway of the flats, and the older children would tell us ghost stories that scared the life out of us. We’d all either dissolve into fits of laughter or scream and run home as fast as our legs would carry us.

Getting caught in the rain and coming home soaking wet and sitting around the blazing coal fire while your wet clothes were drying was so comforting. Staring into the flames, I could see images of anything I cared to imagine, and I loved that.

We would put bread on the end of a very long, large metal fork and hold it over the fire until it was toasted. Before going to bed our mum would bathe us in a large tin bath in front of the fire, which was the absolute centre of our home.

In those days men in Scotland shied away from showing their affection towards their children. It was rare for dads to hug or to cuddle their children, but I used to sit at my dad’s knee and he would dry my hair with a towel and I’d never want it to end. That was his way of showing his affection.

• • •

The older children used to teach the younger ones all the skills they had learned. Lorna taught me how to make tablet, a Scottish sweet a bit like fudge, only more brittle.

Fridges were virtually unheard of then, so we’d put the tablet out on the windowsill in the cold night air and leave it to set. It tasted good even if it was sickly sweet and bad for our teeth.

We also made toffee but managing to do it without getting your fingers burned was an art and gave a sense of self-satisfaction when you got it right.

My brother Ian was the eldest of the three and the quietest. Ian could draw well and tried to teach me but I was never any good. Ian once drew an excellent portrait of our dad sitting in his chair reading the newspaper. My dad didn’t really react and didn’t praise Ian, which I thought was a shame as the drawing was so good.

Whenever the weather was fine we would wander with our friends and have picnics in the fields and make buttercup and daisy chains. When it was cold we would roast potatoes over the glowing embers of a campfire the older children made. That taste is something I remember to this day.

We’d pick and eat wild blackberries and no matter how many we ate there were always loads left over to take home for our mums to make jam. Our clothes were saturated with bramble juice but we didn’t care; it was fun and the juice washed out.

Some of the older people in the allotments would ask the children to help them with their gardening and would give the children carrots and turnips to munch on. They called the turnips tumshies, and we would eat them raw. Can you even imagine children wanting to eat raw turnips nowadays?

One day, when one of our group helped themselves to a turnip without being given permission, the man from the allotment chased us and we all had to run for our lives. It seemed exciting at the time and the relief of getting away safely made us giggle until the tears rolled down our faces.

My dad had an allotment and everything he touched seemed to grow to a huge size; he was forever winning prizes for his vegetables and flowers and we always had loads of fresh fruit and vegetables to eat. Perhaps it was because he was brought up on a croft in a pretty bleak part of the world, where unless you had such talents, survival would have been difficult.

Although I didn’t inherit his green fingers, I did inherit my dad’s love of the outdoors.

When I was little I felt like a free spirit, as much a part of nature as the deer that ran in the forest or the eagles that flew in the air. I wouldn’t have traded my upbringing for the world.

Ever since I was a child I’ve cared desperately about neglected animals. When I was three years old I was playing in the back court in Glasgow. An old lady had put a litter of kittens in the dustbin and put a large rock on top of them and I could hear them crying. Neighbours were standing around looking and shouting at the woman, who was at her window, but no one was doing anything and I couldn’t understand why the adults were all just standing there and wouldn’t save the kittens.

The older children were at school so couldn’t help me. I used every bit of strength I had to try to remove the rock but I couldn’t budge it. I ran to the house and begged my mum to come and save the kittens, but a neighbour told her that it was too late: they were beyond help.

The kittens were hurt and crying and I was too small to help them. I was heartbroken and cried myself to sleep that night. I hated feeling powerless and wanted to grow up quickly.

I felt far too young when I attended my first primary school. I was five years old and dearly missed my mum, even though she would come up to school to see me at playtime and would pass me sandwiches through the railings.

I would sit at my desk gazing out of the windows, longing for the freedom of the outside. I wanted to run in the fields with the wind in my face, instead of being trapped in a classroom wasting my days away.

I always thought it strange that young children, geared to run and jump and laugh and play, were confined to a schoolroom and made to sit still at a desk for seven hours a day. To be at an age when you are full of the joys of life and bursting with energy, and then be forced to suppress that energy seemed odd to me. It was like being put in a straitjacket.

School was a shock to my system and I became quiet and shy when I was there. When my sister Lorna started secondary school I felt so lost and alone that I walked several miles to seek out her school. I have no idea how, at five years old, I could have found my way through miles of busy streets to a school I had never seen, but by sheer luck my sister was one of only two girls out in the playground when I arrived.

In those days I would sometimes see groups of children hanging around outside pubs their parents were in, waiting for money to buy a fish supper. It was a reflection of the times that even some very young children fended for themselves, usually going around in groups with siblings and friends, the older children always looking out for the younger ones.

Times in Glasgow were changing and when the old Victorian tenements where we lived were earmarked for demolition, we moved to a flat in a newly built development on the outskirts of Glasgow. My parents loved having a modern kitchen and a bathroom with hot running water and an indoor coal bunker, but my dad missed his allotment and we all missed our friends and tight-knit community.

I remember after we moved my mum and I heard a man singing in the communal garden of our new flat. Looking out of the bedroom window we saw it was a busker who used to make a living singing in the back courts of our old tenements; as the population moved, he was searching them out in an attempt to continue to make a living. He was a proud-looking man with a strong voice, and he held his cap over his heart as he sang. It was sad, as he was a really good singer, but apart from my mum I don’t think anyone gave him money, and we never saw him again.

CHAPTER 3

THIS IS MUSIC

We had been brought up with virtually no technology apart from a radio, but about a year before we left our old house someone in the street got a TV to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth. We were all invited in, and lots of us sat in our neighbour’s house watching the magical vision of TV for the very first time.

When our old community died I felt that a part of us had died too, but life, like Glasgow, was changing – as was the music.

My sister Lorna, who was almost six years older than I was and still charged with looking after me while my mum and dad worked, took me with her to the cinema for the first screening in Glasgow of the film Rock around the Clock. When we were in the cinema Lorna asked a few of her friends to keep an eye on me, and suddenly Lorna and other people in the cinema were dancing wildly in the aisles to this new music. At the age of eight I was witnessing the beginning of rock ’n’ roll. It was incredible.

Lorna danced like a wild thing, but I wanted to learn how to play the music.

Lorna used to teach me to jive and would throw me over her back no matter how reluctant I was or how much I protested; I had no choice as she was bigger than me.

I used to skip lunch at primary school to run home and play my two favourite Elvis Presley songs, ‘Big Hunk of Love’ and ‘One Night with You’ on a Dansette record player. Headphones were unheard of then but I used to put my ear next to the little inbuilt speaker, cover my head with my coat and turn the volume up full so that I was enclosed in a world of music. I hated having to switch the music off to rush back to school again.

One day Lorna sewed the name ‘Elvis’ onto her top using sequins and rhinestones and I thought it looked amazing. She offered to do the same for me, but my mum said I was too young to go to school with ‘Elvis’ emblazoned across my chest.

I went to bed and when I got up in the morning my mum handed me my top and the large sequined words across the chest read ‘Doris Day’. I could have cried. I looked at my mum and could see how tired she was. I knew she had been up all night sewing it for me and she so wanted me to like it. She had decided that Elvis on my top wasn’t appropriate at my age and had sewed Doris Day’s name on instead. She had no concept of how humiliating this would be for me to wear in school.

I couldn’t bear to hurt my mum so I wore the top and sat mortified in school all day as my classmates teased and ridiculed me. I never wore it again.

Music wasn’t just for kids – my mum adored Frank Sinatra and Irish music, whereas my dad’s taste was more operatic in the style of Mario Lanza. He often sang in Gaelic, his native language.

Even though we sometimes got up to mischief, my mum never hit us, although smacking was common at that time. She herself had a difficult upbringing with an abusive father but she still had an amazing sense of humour and, like many people in Glasgow, possessed an optimism and a strength that carried her through the darkest of times. Even against the most daunting odds she believed that anything was possible, as do I.

I was independent and used to go out on my own and wander through the fields and the woods with my dog. One day when I was walking along the canal bank, two boys had caught a large fish from the canal and I watched it gasping for breath as it was dying in front of me. Seeing the fish struggling to live upset me so much that I gave the boys sixpence to throw it back in the water. Watching it swimming to freedom made me feel so happy.

• • •

I always felt different from other people and it was a huge relief when a new girl named Jean Connolly came to our school. We got on like wildfire and talked continuously, and both of us had an opinion on just about everything – which also caused us to argue at times.

We believed that we could change the movement of the clouds with the power of our thought. We’d cycle for miles and walk across fields barefoot with flowers in our hair, aspiring to emulate the romanticised lifestyle of a gypsy girl we had read about in story books. Our feet not being as tough as the gypsy girl’s meant going barefoot didn’t last long.

We also used to love playing in the fog that would descend on Glasgow at that time. The fog was so thick that sometimes you couldn’t see two feet in front of you. It was like another world or a spooky film and we would call each other’s names and then jump out and grab each other from behind, scaring the living daylights out of ourselves and dissolving into laughter. Coal fires were banned some years later, making thick fog a rarity.

Jean came from a big, warm family. Her dad was a lamp-lighter, who lit the gas streetlights in many areas of Glasgow.

When a fifteen-year-old boy who lived with his grandmother was rendered homeless after her death, he went to live with Jean’s family. This was Charlie McKinnon, who was destined to become a big part of my life.

Glasgow was full of warm-hearted people. Whenever you visited friends, no matter how much or how little they had, they would invite you to have dinner with them and always made you feel welcome.

From the age of eleven I attended North Kelvinside Secondary School, one of the best in the area. Although I was in the top girls’ class and passed exams with flying colours, every stage of school felt like prison to me. School holidays were a huge relief and it was on one of these holidays I found a new love that would underscore my life.

One summer I went to Butlins with my family and this is where I first heard the song ‘She Loves You’ by The Beatles. I had never heard music like this before: it was new and energetic and optimistic and I was in love with this song. My friend Jean and I started going to pop concerts, which is where I first saw and heard another legendary band, the Bee Gees. We started to dress differently from the other girls we knew, trying to look like the girls in The Ronettes, who had the hit record ‘Be My Baby’.

Some of the other girls from school said we looked ‘gallus’ in our black trousers and jackets, but we noticed at the school dance, when our parents made us wear party dresses, that it was girls who seemed prim and as though butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths who were getting up to things that their parents might have been less than happy about.

Jean and I used to stand on the table using a hairbrush as a microphone and sing our hearts out, pretending we were on stage. Eventually we acquired an old tape recorder with a real microphone and we were able to make our own recordings.

Some of Jean’s brother’s friends formed a band, and one day I asked if I could try their electric guitar. I taught myself to play the riff from ‘Peter Gunn’, an instrumental song by Duane Eddy. The boy took the guitar back from me quite abruptly. At the time I thought it was because I hadn’t played it well but when I got older I realised that it was probably because I had played it too well and too quickly.

Because I loved animals so much I wanted to be a vet and thought I would stay on at school to get the qualifications, but when I found out that part of the job would involve putting healthy animals down, I knew there was no way I could do it. So I left school just a few months before my fifteenth birthday. I decided to go out to work and earn my own money while I figured out what I’d like to do with my life.

It was 1963. Glasgow was bursting with energy and with an eclectic mix of musicians, artists, dancers, singers and writers. In May there had been anti-Vietnam War protests in Britain, and music was changing in line with the mood of the people. The world was changing and there was a sense of freedom in the air. I felt I belonged in this brave new world.

CHAPTER 4

BABY, IT’S THE FIRST TIME

One of my first jobs was at a clothes boutique in the centre of Glasgow. It was always busy and the other girls who worked there were full of fun. Occasionally, in a mischievous mood, they would drag their feet along the nylon carpet to build up a static charge in their fingertips and then touch the back of the neck of one of the unsuspecting young male customers, saying, ‘Can I help you?’ The boys would jump at the shock and then join in with our laughter. They never seemed to get annoyed at all.

I had known Charlie McKinnon since I was twelve years old and saw him regularly as he was living with my best friend’s family. We fell in love when I was fourteen years old and got engaged when I was fifteen but I think I loved Charlie from the first moment I saw him. He was and is one of the kindest and most caring people I’ve ever known. He was a huge Elvis fan and an excellent singer, performing in pubs and always working hard at whatever job he was doing.

I saved up all my wages, as did he, and we bought a flat when I was fifteen years old, which was as unusual at that time as it is now.

We were planning to get married four days after my sixteenth birthday, and visited the man from the church to organise the banns. It’s perfectly legal to marry at the age of sixteen in Scotland and no parental permission is needed, which is why for centuries many young couples fled from England to Gretna Green, just over the border, where a marriage can be conducted by a blacksmith.

Gretna Green is still one of the world’s most popular wedding destinations, hosting over 5,000 weddings each year. All the weddings are performed over an iconic blacksmith’s anvil and the blacksmiths in Gretna became known as anvil priests.

Because the church official we had visited was worried about me being so young and was afraid that my parents might not have known I was getting married, he called unexpectedly at our house. The man explained his concerns about my age and my mum told him she had advised me that because of my age the marriage had a higher chance of failure but that in the end I made my own decisions. Charlie was a good person whom my mum and dad trusted and were fond of.

Charlie and I married four days after my sixteenth birthday, as planned. It was a freezing cold December day and Charlie’s friend Jim, Jean’s brother, who was the best man, had flu and collapsed in church during the ceremony. Fortunately he soon recovered and Charlie and I were married, with Jean as my maid of honour. Seeing the photos now, I look like a little girl dressed up as a bride.

We were married the year that hundreds of students demonstrated against the Vietnam War in New York’s Times Square and twelve young men publicly burned their draft cards – the first such act of war resistance.

• • •

Gary was born just over a year later in 1966, the same year the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, refused to send British troops to Vietnam. I was seventeen years old.

My mum had worried that because of my impulsive nature and my age, I might change quite quickly and want to follow another path in life, and in a way she was right. I went into hospital as a very young girl who was in love, happy with her life and about to have a baby, and I came home almost as a stranger, with a totally different outlook.

I looked around the one-bedroom flat that was home and saw it as dark and dull. I was upset because my pet bird had died and I thought that someone had forgotten to feed it. Above all, I felt as though I didn’t belong there anymore. I felt guilty for changing but the change just happened.

When I went out to shops or to the park and saw other girls with their babies, I didn’t feel a connection with them. Many very young girls had three or four children and this scared me so much that I decided then and there that I only ever wanted to have one child.

I also knew I couldn’t live in the same place forever until I died, as many people did at that time. Just the thought of that terrified me.

When Gary was born he was healthy and well but wouldn’t feed. The nurses were concerned about it but left me to deal with it and I was panicking. I don’t remember how long it took or how I managed it but it seemed to take forever before I eventually succeeded.

I used to be fascinated just watching Gary for hours as he lay in his cot. It was amazing that this little life had come from inside me.

I initially saw Gary as a baby that I fed and cared for and was protective towards. I loved it when he gripped my fingers with his tiny hands but when Gary said his first words I was totally smitten – I realised that he was a real little person, and he was my little person.

Gary stood up in his cot one day, looked at us and said clearly, ‘Mammy, Daddy.’ He was about ten months old and from that day on his speech came on leaps and bounds.

Charlie made a brilliant dad. He had an amazing and very natural Glasgow sense of humour, like Billy Connolly, and he made everyone laugh.

Before Gary was born I had a dream about a baby with a mischievous face, auburn hair and freckles, wearing a nappy and running through puddles. I told my family about the dream but voiced doubt that any baby of mine would have auburn hair and freckles as I had dark hair.

Sometimes I feel as though life is scripted in some unfathomable way and then occasionally, just occasionally, little snatches of this great narrative are revealed in a dream or a moment of déjà vu.

When Gary was born he had downy black hair and blue eyes, but his eye colour changed from blue to green and as time passed his hair became a beautiful shade of auburn.

So gradual was the change that it was only when he was about eighteen months old that I recognised Gary as being the baby from my dream.

• • •

From the age of two or three, Gary was obsessed by space and used to lie in bed beside me, talking about the stars as we gazed up at the night sky through the bedroom window. He wanted to know the names of the planets and how far away they were, and seemed to grasp concepts of space that eluded me. He had an unusual way of seeing but often made an odd kind of sense. When he was about five years old he said, ‘Mummy, was Noah’s Ark a spaceship?’

‘Well, I suppose it might have been, I hadn’t really thought about it.’

‘Well, do you think Noah just took seeds of all the different animals so that he could grow them later? Because there wouldn’t have been enough room for all of the animals, would there?’

My marriage to Charlie drifted into friendship and it seemed that my mum was right. Many people who marry at such a young age often change so much that their lives take them down separate paths, causing the marriage to break down.

Gary was five years old when we separated but his dad, who is now happily married to Jeanna, has remained close to Gary and is a major part of his life. Jeanna and Charlie have three sons together and Charlie also has a daughter, giving Gary four siblings. Charlie was a huge part of my life and knowing he is happy makes me happy.

I met Wilson when Gary was six years old and quickly discovered that as well as being a musician, Wilson was into space, UFOs and science fiction. He used to live near Bonnybridge, a place that’s often referred to as the UFO capital of the world. Naturally, Gary liked this idea and quizzed Wilson constantly on this subject.

We moved to London in 1972, where there were more work opportunities for musicians and artists like Wilson. There was already serious interest in Wilson’s band Aegis, and a producer of note had arranged to record them in a top London studio.

We arrived in Muswell Hill in north London; a friend from Glasgow named Dougie Thomson was renting a flat there and we stayed with him for a few nights.

Fate can be quite amazing sometimes. While in Glasgow Dougie, who was a bass player, had once told us that he intended to quit his band, The Beings, and travel to London to get a job with either of his two favourite bands – The Alan Bown Set and Supertramp.

Dougie Thomson arrived in London and had been there for only weeks when he joined The Alan Bown Set; he had the advantage of knowing all their songs inside out. As if that wasn’t amazing enough, a short time later Dougie went for an audition with his other favourite band, Supertramp, and again he knew all the songs, played brilliantly, got the job and became a key member of Supertramp.

It was coming up to Christmas and Wilson and I were searching for a place to live. We were standing outside Highgate tube station when a young guy with long hair and a cockney accent came up to Wilson and said, ‘Hi man, I’m Johnnie Allen, we were at school together. What are you doing here?’

‘We’re looking for a flat.’

‘Come back to ours, everyone is away on tour and you can stay there.’

Johnnie was working as the road manager for a band named Uriah Heep. He was just about to go off to Italy on tour, so we happily accepted and went with him back to the large Edwardian flat in Muswell Hill. Johnnie was pleased I was there as he thought I could cook Christmas dinner, including a large turkey he’d bought. He looked so disappointed when I told him I was a vegetarian and couldn’t bring myself to cook the turkey.

The flat had lots of large rooms with high ceilings and French doors that led onto a beautiful garden. Johnnie told us we could stay as long as we wanted. He then left to go on tour and every time someone from one of the bands arrived home we had to explain who we were, which we dreaded as it was so embarrassing.

Eventually James Litherland, whose flat it actually was, arrived home. Jim had played and sung with the band Colosseum, and luckily he recognised Wilson as they had played at some of the same venues. Jim was kind and friendly and said it was fine for us to stay there until we found a place of our own, which we did very shortly afterwards.

Jim has remained a lifelong and very dear friend, and is one of the kindest and most caring people we have ever met, as is his wife Helen. Their son James Blake is now making his own mark on the music world.

The Vietnam War was on everyone’s mind at that time and musicians like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young played their part in exposing its brutality and helping to end it.

Through the efforts of people such as John Pilger, the photo of a nine-year-old Vietnamese girl named Phan Thi Kim Phuc running naked down the street, her body burning with napalm, was broadcast. The worldwide protests against the war and the outrage of the American people in reaction to this image were what finally led to the end of US involvement in the Vietnam War in August 1973.

• • •

In 1974 Wilson and I got married in Wood Green to the music of Pink Floyd – an edited version of ‘Us and Them’, extending the instrumental to last throughout the ceremony before David Gilmour’s voice came in on the verse.

Wilson looked every inch the musician with his long hair and d’Artagnan-style moustache. An excited Gary looked beyond cute and my mum had travelled down from Glasgow to be with us.

I love London. I’ve loved it since the day we arrived here. I love the buildings, the history and the fact that when you stand in Westminster Abbey you are surrounded by the spirit of so many great figures you were taught about in school.

We continued to live in Muswell Hill and Gary attended Muswell Hill Primary School. One day while sitting at the kitchen table Gary asked us when the world was going to end and we reassured him that it would be around for a very long time. He was obsessed with the end of the world and kept pressing us for a date, and was agitated and upset that, instead of telling him when, we were trying to reassure him that it wouldn’t be ending until long after we were all gone.

Gary then asked if I was going to die one day and I told him yes, everyone dies sometime. He dissolved into tears. He then asked if Wilson was going to die, if his dad was going to die and if his grandma was going to die, and he cried more and more when I told him again that everyone dies sometime but that it wouldn’t happen until we were very old, which would not be for a very, very long time.

No matter how much I tried to comfort him, Gary was inconsolable. He missed his dad and wanted us all to be together; Charlie eventually moved to London to work and met his new wife Jeanna, which was great for Gary as he then had everyone he loved around him.

Although Gary was only six years old he had already been taught fractions and some French at Dunard Street School in Glasgow, and had started reading at the age of three. When he started at Muswell Hill Primary School the class was being given counters to learn how to count and Jack and Jill books to read – Gary was bored as the education seemed to be years behind his previous school. Although I was surprised at this, I quickly realised that the school excelled in English and was very good at giving children confidence in themselves and encouraging them to develop good communication and social skills, something Gary needed help with.

Gary became restless and would sometimes wander out of school and come home, and I’d have to take him back again. He liked being at home, as he felt he didn’t fit in at school and was becoming more and more unhappy there. Gary preferred the company of adults. His classmates bullied him for being ‘different’ and his Scottish accent also set him apart. There were basic skills and concepts that he found difficult to grasp and this was at odds with his obvious intelligence.

Gary had difficulty opening all sorts of things, but would take toys and locks apart to see how they worked – never putting them back together again. He also had difficulty following instructions and I used to think he was having us on. He would often get the wrong end of the stick because he took everything literally. His directness could also be misconstrued as rude and could sometimes make people feel awkward.

We only holidayed abroad once because of Gary’s fear of travel and resultant meltdown when he was too far from home.

His was a literal world, a world of logic; outside of that world chaos reigned.

CHAPTER 5

FIRST LOVE

I started learning to play the guitar just before I left Glasgow and was obsessed with it. Wilson bought me a Fender Telecaster which I used to play almost every day. After I moved to London I started rehearsing in a King’s Cross studio with other girls, who played bass and drums. Jackie Badger from Islington was the bass player, but we had difficulty finding a good female drummer until a young, slim, dark-haired American girl named Holly Beth Vincent walked in and played like a pro. This was our very first band and all three of us are still in regular contact with each other.

Holly eventually formed her own band, Holly and the Italians, and Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits became her boyfriend; a few of Dire Straits’ hits were songs that Mark wrote about Holly, including ‘Romeo and Juliet’.

My friend Jackie rang me one day and asked me to join a girl band she was in named Mother Superior, as they had lost their guitarist. I joined them on a tour of the UK; I had never played a gig before, but being thrown in at the deep end improved my guitar playing and, although daunting, it was an amazing experience.

I missed Gary and Wilson when I was touring and although the band was getting great reviews, when the tour ended I decided to leave.

A few months later I answered an ad in the Melody Maker for a female guitarist. Miles Copeland rang me up and arranged for me to go to his house for an audition. Unfortunately someone told me that it wasn’t a good idea and gave me lots of reasons, with regard to the music business in general, as to why I shouldn’t go, so I didn’t.

Miles Copeland rang back the next day to ask me why I hadn’t turned up, and I was embarrassed and apologetic, and annoyed with myself. Some time afterwards Miles Copeland put the girl band the Bangles together; when the band The Police were formed, it was Miles who managed them, with his brother Stewart Copeland as their drummer.

I started writing songs and, rather than playing separately, Wilson and I decided to form a band together – named Axess, then renamed Who’s George, and finally The Walk. We advertised for a vocalist but couldn’t find one that we were happy with, so I started singing the songs I wrote.

We toured universities and played all around London – at Dingwalls, the Rock Garden, Camden Palace (now KOKO) and the Venue, among others. Our songs were played on the radio and one of my songs scraped into the charts and we had the occasional TV appearance.

At one of our Camden Palace gigs it was announced that Elvis Presley was dead. Charlie, Gary’s dad, was there and was incredibly upset by this news. Everyone in the hall was in a state of shock and disbelief. A legend had died.

Gary had always loved music but wasn’t interested in playing any instruments until he was about seven years old, when one day Wilson and I were in another room working out a song I had written. We heard Gary banging discordantly on the piano, suddenly followed by grand chords being played in a classical style. Wondering who else was there, we peeked into the room and saw Gary playing the piano with both hands, utterly absorbed.

‘God, Wilson, can you hear that? That’s Gary. Where did that come from?’

There was our little Gary sitting playing these powerful, dramatic chords that left us with our mouths open as we peeked from behind the door. We were enthralled and didn’t want to leave, but we didn’t want to stay either, or he’d become aware of us and stop.

We moved home shortly after this and didn’t have a piano until a year or two later, so Gary used to go to a neighbour’s house to practise. One day she came to our door and I invited her in.

‘You really have to send Gary for piano lessons, Janis. I’ve been having lessons for years and without any guidance Gary can play much better than I can, so just think what he could do if he had lessons.’

Little did she realise that we had enough difficulty paying for our rent, let alone for piano lessons.

A year or two later we bought a grand piano from an auction for about £300. It cost us more to have it delivered than it did to buy. We spray-painted it white as I wanted it to look like John Lennon’s piano in the ‘Imagine’ video. Gary, about nine years old at the time, taught himself to play the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata in a matter of days.

The first time we heard Gary sing was another revelation. He had just come home from a local community group he attended in Crouch End called Kids & Co. They wanted the children to learn a song to perform, so Gary asked us if we’d record him singing. I said, ‘Right, what song do you want to do?’

‘“She’s Leaving Home”,’ Gary replied.

‘The Beatles song? You know it’s not the easiest song in the world to sing if you’ve never sung before.’

‘But that’s the one I want to do.’

‘OK,’ I said, thinking that this just wasn’t going to work. Gary used to wander around with headphones on and when he sang along it sounded so awful we’d decided that as far as singing was concerned he was tone deaf. So when Gary started to sing ‘She’s Leaving Home’ we were blown away by this deep, haunting voice that flowed effortlessly.

He was so modest and unassuming that no one realised what he was capable of. Unfortunately Gary was excluded from Kids & Co. shortly after that as he apparently didn’t listen to or wouldn’t follow their instructions. Becoming excluded from things was happening too often and would be difficult for anyone to take. I knew how hard Gary had been trying to fit in, to find his place in the world, but because he felt he was failing, he was becoming more and more isolated. To be so talented yet so undervalued by people seemed so damned unfair.

What is to ‘fit in’ anyway? To try to fit in is to try to become ordinary and be conditioned not to raise your head above the parapet or stand out from the crowd. If someone is ‘different’, why should they be expected to strive to become ordinary?

Encouraging people to manage their differences and to express themselves through whatever medium they can, and encouraging others to accept and value those differences, is surely what society should strive for. Whether that medium is music, art, computing, cooking, gardening or being good with animals, all are equally valid. We are all links in a chain that make our society what it is.

Not all who are different are talented, but many are. Michelangelo was by choice a solitary figure who slept in his clothes, shunned the company of his fellow man and had no interest in food other than as a necessity.

Great thinkers such as Isaac Newton did not fit in; the suffragettes were extraordinary women who rebelled in a way that shocked society.