Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

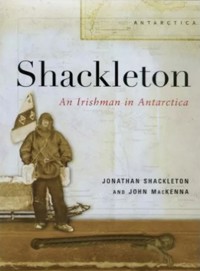

A mesmerizing new biography of explorer Ernest Shackleton, lavishly illustrated with over a hundred photographs, maps and engravings, some of them appearing in print for the first time. Eighty years after his death, the extraordinary story of Endurance South Pole expedition still holds a compelling grip on the public imagination. Trapped in drifting polar pack ice for ten months, Ernest Shackleton and his crew fought for survival against all the odds. When the Endurance was finally crushed, they were stranded on the ice for more than a year, before reaching Elephant Island. Two weeks later Shackleton and five companions embarked on the most remarkable rescue mission in maritime history, sailing to South Georgia over eight hundred miles of the roughest seas in the world in a small open boat. This book probes deep into family history to reveal the profound influence of Ernest Shackleton's Irish Quaker roots in the making of a great leader. The fruit of intensive research, Shackleton: An Irishman in Antarctica paints a vivid portrait of a man whose ambition was always tempered by his humanity and egalitarianism. Here too are the untold stories of Shackleton's upbringing in Kildare; his time in the Merchant Navy; his marriage and love affairs; his life as public man and politician; and the haunting story of his final – and fatal – expedition on the Quest. Drawing on family records, diaries and letters – and featuring hitherto unpublished photographs and archive material – this mesmerising book takes us beyond the myth to Shackleton the man, showing us a hero who eschewed imperial hierarchy and whose greatest triumph was that of life over death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2003

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Shackleton

AnIrishmaninAntarctica

JONATHAN SHACKLETON AND JOHN MACKENNA

To Daphne, David, Jane and Hannah for their support

For Eoin O’Flaithearta

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1 Irish Family Background

2 Merchant Navy Years 1890–1901

3 Antarctica and Polar Exploration

4 South with Scott 1901–1903

5 Shackleton at Home 1903–1907

6 The Nimrod 1907–1909

7 Knighthood and the Public Man 1909–1914

8 The Endurance and Aurora 1914–1917

9 Shackleton and the Great War 1917–1921

10 The Quest 1921–1922

11 The Legend

Bibliography & Recommended Reading

Acknowledgments & Illustration Credits

Index

Copyright

Shackleton

An Irishman in Antarctica

SHACKLETON FAMILY TREE

1

Irish Family Background

The man was standing at the foot of the long incline, watching seven figures on the horizon. The first was moving carefully, the other six fanning out behind across the white countryside. The group travelled in a line, edging down the side of the slope, bent low against the sun. Gradually, the last of the seven began to lose contact with the others, his pace slowing, dropping farther and farther behind, until, finally, he came to a halt and crouched in the blinding whiteness. The others went on, too intent on their own expedition to notice his loss. Only when they had reached the security of level ground at the foot of the hill did they stop to take stock. The leading figure, by far the tallest of the seven, glanced back along the track they had descended and saw the distant figure, all but lost in the whiteness of the landscape.

‘Mr Lag!’

There was no response from the distant figure.

‘Mr Lag!’

The voice was louder now.

The crouching figure looked up, disorientated and surprised at how far he had fallen behind his comrades. Rising slowly and taking his bearings, he trudged down the hill, the snow-white heads of cow parsley hanging across his path.

‘We can’t wait all day for you, kindly keep up with the rest.’

‘Yes.’

‘Now, on we go. Gertrude, you walk behind Ernest. That way we may keep from losing your brother. Again.’

And so the procession continued across the foot of Mullaghcreelan Hill. The nurse leading her charges through the long summer grasses, Amy and Frank and Ethel and Ernest and Eleanor and Gertrude Shackleton following in her footsteps.

The watching figure, Henry Shackleton, the children’s father, turned back to examine his beloved roses, smiling at the picture of his eldest son, lost among the wild flowers, living in a world of his own.

The Shackleton children making that afternoon journey across the fields near Kilkea, in the south of Co. Kildare, were the descendants, on the one hand, of a family whose roots ran back to Quaker stock and who had arrived in the area two and a half centuries earlier. On the other, the family tree was grounded in the Fitzmaurices, a wild and adventurous Kerry family.

KilkeaHouse.BuiltintheearlynineteenthcenturyfortheDukeofLeinster.LeasedbyErnest’sfatherHenryShackletonc.1872–80;sixofhischildrenwerebornthere.

The Quakers, or Religious Society of Friends as they were more formally known, were founded by George Fox in the north of England in the mid-seventeenth century. The sect, like other similar groups of the time, was intent on moving away from the structured forms of the Church of England and the Catholic Church. William Edmundson had brought the ideals of the Quakers to Ireland, establishing the first Irish Quaker meeting in Lurgan in 1654.

What marked the early Quakers out from the plethora of other sects of their time was their belief in the Inward Light, a phrase they used for the direct link they believed themselves to have to the Holy Spirit. Not for them the notion of a clerical hierarchy of middlemen through whom God might be reached.

The Quakers, who earned their colloquial name from the custom of members quaking during meetings, were non-violent in creed and practice and brought a stringency of clothing, lifestyle and business to their daily lives.

Women and men were treated equally within their fellowship, and indeed women were among the earliest preachers of Quakerism in Ireland, though by 1700 their preaching was being discouraged by the Elders and their position eroded by the late seventeenth-century influx of soldiery into the ranks of Irish Quakerism.

Not surprisingly, the Quakers in Ireland were to live paradoxical lives. Not only did they bring a new religious belief and practice into the country, they also laid the foundations for the development of a trader class that was, on the one hand, distinct from the Anglo-Irish Protestant landlords and, on the other, separate from the Irish Catholic peasant class. The more prominent early Irish Friends became known outside their own community through their involvement in business, and among the better known family names were Bewley, Jacob, Shackleton and Lamb. While both Protestant and Catholic ranks may have been envious of the newly emerging merchant group, their envy was tempered by the lack of ostentation shown by the Quakers. They had no desire to clamber into the world of the big house, nor to proselytize among their poorer Catholic neighbours.

Despite the attempts of the early Quakers to live quiet lives, they didn’t always escape the often unwelcome attentions of their fellow citizens. Their dress, religious beliefs and refusal to swear oaths, use the names of days and months or the pronoun ‘you’ or even to have images on their chinaware, made them easy targets for vilification.

One of the earliest Quaker settlements in Ireland was at Ballitore in Co. Kildare, thirty miles south-west of Dublin. The first Quakers to arrive in the village had been John Barcroft and Abel Strettel, who bought lands there in the 1690s. They arrived into an already established but poverty-ridden community. The local land was poor and poorly cared for. Barcroft and Strettel set about changing that, planting trees, orchards and hedges, putting their own kind of order on the wilder landscape that had met them on arrival.

In 1708 a Meeting House was completed in the village, with others built in the nearby towns of Carlow in 1716 and Athy in 1780 (although the first Quaker meeting here was held in 1671).

ShackletonHouse, Harden,Yorkshire.ThefamilyownedtheHardenpropertyfromthesixteenthcentury.Thehousewasdemolishedin1892,whenthedoorandlintelstonewerebroughtbytheShackletonstoLucan,CountyDublin,andin1983giventotherestoredQuakerMeetingHouseinBallitore,CountyKildare.

While most early Quakers in Ballitore made their living from industry and farming, Abraham Shackleton chose to open a boarding school in the village in 1726, beginning the Shackleton connection with Quaker life in the area.

The Shackletons came from the village of Harden in West Yorkshire, England, and Abraham had been born in 1696. The studious youngster had lost both parents before his eighth birthday but he showed a tenacity that was to stand to him in establishing his school. As a young man he became an assistant teacher in Skipton where he met his wife, Margaret Wilkinson. He then travelled to Ireland as a tutor to the Quaker Cooper and Duckett families, who lived at Coopershill, near Carlow, and at Duckett’s Grove, on the border of counties Carlow and Kildare, less than ten miles from Ballitore. Encouraged by these two families, Abraham established his school.

The initial roll for the school numbered thirty-eight pupils. Two years later the numbers had grown to sixty-three. The school became so successful in such a short time that its reputation drew students from as far afield as France, Norway and Jamaica. Many children, arriving in Ballitore at the age of four, were to remain there without seeing their parents again until they were eighteen. Some of the boys, falling prey to measles or smallpox, were never to return home, dying in the village to which they had come to be educated, far removed from parents and family. These tragedies, when they occurred through the years, cast shadows over Ballitore where everybody knew everybody else and many pupils lodged in local houses, integrating fully into village family life.

The curriculum in Ballitore School included the classics, history, maths, geography, English literature and writing and composition. Not all the teachers or pupils came from Quaker backgrounds and early alumni included the statesman Edmund Burke (1729–97), the revolutionary Napper Tandy (1737–1803) and the future Cardinal Paul Cullen (1803–78).

RichardShackleton(1726–1792)whosucceededhisfatherasmasterofBallitoreSchoolin1756until1779,wasafoundingmemberofBurke’s‘Club’atTrinityCollege(apredecessoroftheHistoricalSociety),andalifelongfriendofEdmundBurke.(CourtesyDesnaGreenhow)

Abraham and Richard Shackleton. Abraham (1696–1771), born Harden, Yorkshire, where his father was the first of the family to be a Quaker, came to Ireland in 1720 and opened a school in Ballitore, County Kildare in 1726.

ShackletonSchool,Ballitore.Openedonthefirstofthethirdmonth1726byAbrahamShackletonandclosedin1836,havinghadoverathousandpupils.Buildingdemolishedc.1940.

When Richard Shackleton, Abraham’s son, born in 1726, took over the running of the school thirty years later, he broadened the curriculum while introducing a more stringent regime, leaving little room for amusement. (His stringency led, on at least one occasion, in 1769, to the pupils locking the staff out of the school, demanding a summer holiday. Pacifist or not, the headmaster quickly broke down the school door and the boys were thrashed.) Richard had been a schoolmate and friend of Edmund Burke’s in Ballitore and an observer of their student days commented that Shackleton was ‘steadier and more settled than Burke was ever to become’.

Richard had received his first and second level education in Ballitore and had gone on to study languages at Trinity College in Dublin, the first Quaker to do so. He was an active member of the Historical Society and received a special dispensation to address the Society while wearing his hat – a Quaker practice based on the belief that all people were equal and none in particular merited the doffing of a hat. The attractions of theworld might have drawn another young man away from Ballitore and Quakerism but not Richard. He was single-minded in his commitment to his faith and his education.

Eighteenth-century Quakers were forbidden from taking degrees so Richard, having completed his studies in Trinity, returned to the quieter and more austere life of a schoolmaster in Ballitore.

At the age of twenty-three he married Elizabeth Fuller, a granddaughter of John Barcroft, one of the original settlers at Ballitore. The couple had four children. Elizabeth died in 1754 and a year later Richard married Elizabeth Carleton. They had two surviving children – Elizabeth and Mary.

Mary was to leave a legacy of history, culture and literature through her poetry and prose. Richard had insisted his daughters receive as wide an education as his sons and in Mary’s case he greatly encouraged her in her writing. When he travelled abroad, to London and Yorkshire, Mary travelled with him. While visiting cousins in Selby in Yorkshire, they were invited to tea in house after house. Typically, Mary noted in her diaries that the silver coffee-pot from the local big house was there to greet them on each tea-table in turn.

MaryandWilliamLeadbeater.Mary(1758–1826),daughterofRichardShackletonandhissecondwifeElizabeth, wasaprolificpoet,correspondentanddiarist.William(1763–1827),Mary’shusband,anorphan,attendedBallitoreSchool.TheirdaughterLydiaFisherwasasecretloveofLimerick-bornnovelistGeraldGriffin(1803–40).PlainsilhouettesweretheusualformofportraitforQuakers.

Born in 1758, Mary had developed both an academic and a personal friendship with the other pupils in Ballitore School. One of her close school friends, William Leadbeater, was to return to Ballitore as a teacher and, at the age of thirty-three, Mary married him. All the while, Ballitore School was growing in size – as many as twenty-three new pupils enrolling in one year.

Richard Shackleton died of a sudden fever in 1792, on his way to a school board meeting in the town of Mountmellick. He was sixty-six. The running of the school was now taken over by his eldest son Abraham.

Abraham was to undo many of the changes his father had made. Where Richard had widened the curriculum, Abraham narrowed its focus. Where Richard had thrown open the school doors to a multitude of denominations, Abraham restricted entry to Quakers.

As the eighteenth century drew to a close, Abraham married Lydia Mellor and set about tracing the family history, bringing to light, among other things, the family crest and motto, FortitudineVincimus–ByEnduranceWeConquer.

Whether the changes introduced by Abraham would have led to the decline that followed in Ballitore School is impossible to tell, but the rebellion of 1798 brought an immediate dip in its fortunes. That the rebellion should occur in that year was hardly surprising. Ireland in the 1790s was a country riven with dissension. It had a parliament established for its minority community, while its Catholic population was petitioning for King and Parliament to ‘relieve them from their degraded situation and no longer suffer them to continue like strangers in their native land’.

In April 1790 a meeting was held in Belfast where those attending agreed to ‘form ourselves into an association to unite all Irishmen to pledge themselves to our country’. Thus was the foundation laid for the founding of the revolutionary United Irishmen, whose first Secretary was Napper Tandy, former pupil of Ballitore. Through the 1790s the United Irishmen worked to establish their organization across the country. They drew inspiration and aid from revolutionary France and their ambition was a rebellion that would overthrow British dominance in Ireland and establish an independent state, unifying Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter against the imposition of rule, through a puppet parliament, from Britain. As the power of the United Irishmen grew, Parliamentary Acts were introduced in 1794 to outlaw their meetings, but the organization continued, underground, as a secret society. The following year a Catholic Relief Bill, designed to make daily life easier for the vast majority of the population, was defeated in Parliament.

Nor were the United Irishmen the only ones with an interest in Ireland’s political future. In 1779 the first regular Volunteer Corps was founded in Belfast. The immediate objective of the Volunteers was to defend Ireland, in the absence of sufficient British troops, against invasion by French or American marauders. The incident, which sparked panic among the citizenry, was the capture of a ship in Belfast Lough by American privateer Captain Paul Jones.

MaryLeadbeater’shouse,Ballitore.FromhereMaryrecordedmanyofthecomingsandgoingsinthevillage.Buildingrecentlyrestoredandopentothepublic.(Photographc.1890s)

Initially, the Volunteers were Protestant but they were armed, and an armed group of citizens was a frightening prospect for the government. And worse, as the Volunteers spread, Catholics were welcomed into their ranks and an organization that had started as a last line of defence quickly became a potential threat.

The drain of British soldiery from Ireland reached crisis point in the 1790s because of war with France. England’s problem was seen, by the United Irishmen, as their opportunity to push for a full rebellion and by those loyal to the Crown as a chance to establish a Yeomanry force within the country.

Arrests of suspected United Irishmen continued through 1796 and 1797. In October of that year habeascorpus was suspended to deal with trouble from both the United Irishmen and the emerging loyalist Orange Order.

Early in 1798 the United Irishmen in Leinster resolved that they ‘would not be diverted from their purpose by anything which could be done in parliament’. In May a rebellion organized by the United Irishmen broke out in many Leinster counties, including Kildare. Ballitore did not escape the bloodshed.

Parents, fearing for their children’s welfare, in a village where violence, warfare and murder had become commonplace, removed them as quickly as possible. Despite the fall in numbers, the school struggled on until in 1801 Abraham decided to close it.

Several years earlier William Leadbeater had left teaching and gone into business and Mary had opened the first Post Office in Ballitore. This allowed her to continue her writing and kept her well informed about local comings and goings. While her main concern was with local life, Mary also corresponded widely with people like Edmund Burke and the novelist Maria Edgeworth (1767–1849), as well as a wide circle of past pupils across the globe. While Burke had been an acquaintance at school, Maria Edgeworth became an epistolary friend. Their letters grew out of a shared interest in the improvement of the peasantry and in the education of women, a topic Edgeworth had used for her first publication, LetterstoLiteraryLadies, published in 1796.

It is Mary’s insatiable appetite for gossip that makes her diaries so interesting. They were published long after her death as TheAnnalsofBallitore (1862), generally called TheLeadbeaterPapers, and deal with the period 1766 to 1824. They include one of the few impartial accounts of the 1798 rebellion, which began on 23 May and continued with sporadic fighting until mid-July.

At the end of 1798 Mary noted the constant presence of the reminders of loss in her own and others’ lives.

‘Late one evening, as we leaned over the bridge, we saw a gentleman and a lady watering their horses at the river, attended by servants fully armed. They wore mourning habits, and though young and newly married, looked very serious and sorrowful. Their chastened appearance, their armed servants, the stillness of the air scarcely broken by a sound, rendered the scene very impressive … Mourning was the language – mourning was the dress of the country.’

Mary was also deeply involved in the movement to ‘improve’ the peasantry and to promote ideals of progress, abstinence, thrift and self-esteem. These were the principles evinced by her grandfather and father through Ballitore School, and she was anxious that they become part of the lives of those about her.

In 1806, five years after the school had closed its doors, Abraham Shackleton’s son-in-law James White reopened them and with the return of peace to the countryside the classrooms quickly filled with students from Ireland and elsewhere.

Abraham, however, decided not to become reinvolved and turned, instead, to milling as a second profession, running the family mill at Ballitore and continuing to work there until his death in 1818. Milling carried through to the next generation with Abraham and Lydia’s son Ebenezer, who bought a mill in the village of Moone, a couple of miles along the road from Ballitore.

Ebenezer, born in 1784, had grown up in a Quaker family but from early adulthood questioned the direction Quakerism was taking in Ireland, believing the community was straying from its original ideals. He took this as his main reason for converting to the Church of Ireland and bringing his children up in that faith. One of those children was Henry Shackleton, father of the young walkers spread out across the sunlit fields on Mullaghcreelan Hill.

JamesWhite(1778–1847),masteratBallitoreSchool(1806–36),marriedthepreviousmasterAbrahamShackleton’sdaughterLydia.TheirdaughterHannahmarriedateacherattheschool,TheodoreSuliotandtheyemigratedtoOhio.AfterLydia’sdeathWhitemarriedMaryPike.(AmbrotypecourtesyJeremyWhite)

Termsofenrolmentofschoolin1832.

On the other side of the family, the children’s mother Henrietta was the daughter of John Henry Gavan and Caroline Mary Fitzmaurice. Henrietta’s mother was the daughter of John Fitzmaurice of Carlow, himself the great-grandson of William Fitzmaurice, the twentieth Baron of Kerry.

The Fitzmaurices, through marriage into the Petty family, had inherited large tracts of the Petty estate of 270,000 acres in Kerry. (William Petty (1623–87) had been Cromwell’s physician-general and surveyor.) But their roots in the area went back much further, to Thomas Fitzmaurice who had arrived as part of the Norman force in Ireland in the twelfth century. Fitzmaurice had been styled the First Lord of Kerry. The earldoms of Kerry and Shelbourne and the title of Marquess of Lansdowne were subsequently created for members of the Fitzmaurice family.

Not that the Fitzmaurices had escaped political and military troubles in the course of Irish history. In the Geraldine rebellion of 1579 the family had much of their lands seized and sold.

In July that year James Fitzmaurice had landed at Smerwick harbour in Co. Kerry and established a base at Dún an Oir with a force of Spanish and Italian soldiers. The Papal Legate, Nicholas Sanders, accompanied him, with letters from the Pope to the Irish Lords discharging them from allegiance to Queen Elizabeth of England and urging them to rebel in support of the Catholic faith. Two months later Fizmaurice was killed in a skirmish with the Burke clan in Co. Limerick.

Ebenezer Shackleton (1784–1856), married secondly Ellen Bell, grandparents of EHS. Ebenezer took on the Moone Mill in 1824 and lived at Moone Cottage (now demolished). (Courtesy the late Betty Chinn)

In 1691 lands were again confiscated when James and Henry Fitzmaurice remained loyal to King James against King William. Later, the family returned to the safer confines of the establishment. The First Marquess was First Secretary and then Prime Minister in Britain from 1782 to 1783. The Third Marquess was Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1806 to 1807 and later Home Secretary. The Fifth Marquess was Viceroy of India from 1888 to 1894 and subsequently British Foreign Secretary.

On the Gavan side, Henrietta was descended from a family connected to church and state. Her father, Henry, had been involved, with his father Rev. John Gavan, rector of Wallstown, Doneraile, Co. Cork, in the battle of Wallstown, a tithe-assessing incident (whereby a tenth of annual produce was levied in support of the Anglican Church) which occurred in September 1832.

Rev. John Gavan was an unpopular man in the area. He and his son had gone, one afternoon, to mark tithes on a farm. Once there, an angry crowd surrounded them. The Gavans drew their pistols but were disarmed. The following day, with three magistrates and a number of policemen, they went to another farm. Some stoning of the police and magistrates, mostly by women and children, followed and, apparently, one of the magistrates, a man called Evans, panicked and ordered the soldiers to open fire on the crowd. Four of the tenants were killed, one a boy of fourteen, and many were injured. A subsequent investigation suggested that the turning points that led to the heightening of tensions and the subsequent deaths were Henry Gavan’s over-zealousness and Evans’s panic.

Henry had originally studied medicine and qualified as a doctor but his interest lay in joining the Royal Irish Constabulary. Through the political influence of Lord Cornwallis, Henry obtained a commission in the RIC, and after his marriage in 1844, to Caroline Mary Fitzmaurice of Carlow, he was appointed Inspector General of Police in Ceylon.

Henry and Caroline sailed from Falmouth for Ceylon on the Persia. Shortly after its departure, the ship was forced to return to Falmouth after a ten-day buffeting at sea. The Gavans refused to re-embark. Such was the ferocity of the experience, Henry never fully recovered and he died two years later, leaving his wife and an infant daughter, Henrietta Letitia.

Henrietta’s birth, on 28 September 1845, came just two weeks before the first reports of a widespread potato failure in Ireland. Over the following three years Ireland would go through the bleakest period of its history. Failure of the staple diet crop of potatoes through 1845, ’46, ’47 and ’48 was mirrored by trader speculation which saw the price of corn rise beyond the means of the destitute, and by government inaction. The relief measures introduced were often ill-conceived and badly organized.

Help did arrive from abroad, mainly from the United States, but distribution was haphazard. By 1848 more than a million people had died from starvation and malnutrition. Those who were healthy enough and could find the fare emigrated, leaving a devastated country. For those who stayed, eviction was a constant threat. With crops continuing to fail and no money available for rents, the poorhouses and roadsides were thronged with evicted families. By 1 July 1848, almost 840,000 people were in receipt of relief.

The Great Famine, however, was not a matter of life and death for all classes in Ireland. Caroline Gavan had lost her husband but neither she nor her daughter was in any danger of falling victim to starvation or emigration. The effects of the famine did not impinge materially on the lifestyle of the Gavans or their class.

Brought up by her mother, Henrietta grew into a bright, vivacious and good-humoured young woman. On 28 February 1872 she married Henry Shackleton and moved with him to live at Kilkea House, a large square, comfortable farmhouse. To the side, as one entered, were solidly built, slated stone outhouses which enclosed a courtyard.

Everton,Crockaun,CountyLaois,aFitzmauricehouseoutsideCarlowfromwhereEHS’sparentsweremarried.KelvinGroveandLaurelLodgewereotherFitzmauricehousesintheCarlowarea.

The house was surrounded by rolling grassland that rose along the flank of Mullaghcreelan Hill on one side, and fell to the banks of the river Griese on the other. It was rich land, good for tillage as well as cattle and sheep rearing.

Henrietta’s verve and sheer good humour were to help her create – even in difficult times – a sense of order, enjoyment and support for her children at Kilkea. Unusually in a Victorian family, both Henry and Henrietta were constantly available to their children, including them in virtually all family activities, listening and advising and, most of all, encouraging them to express themselves.

These two family lines – hardworking Quaker pacifists and hot-blooded adventurers – were to find a perfect point of fusion in Ernest.

Bent low between his rose bushes, Henry’s thoughts had moved away from the sight of Ernest, lost in wonder among the cow parsley, to the more pressing business of money. He had hoped to make a living as a farmer and find time and opportunity to develop his interest in homoeopathy, but, confronted with falling prices and a downturn in the agricultural economy, he faced the possibility of a change of career. It wouldn’t be his first.

Henry had been sent to school in Wellington College in England, carrying his mother’s hopes of an army commission, but ill health had brought him back to Ireland and to Trinity College in Dublin, where he took an Arts degree in 1868.

Four years later, when he married Henrietta, they opted for a life of farming. Land was leased from the Duke of Leinster and the couple set up home at Kilkea House. The farm, set close to the hamlet of Kilkea – built to house workers on the estate of the Duke of Leinster – was equidistant from the market towns of Athy and Carlow and close to the village of Castledermot.

With family connections on both sides, they were five miles from Henry’s birthplace and seven miles from Henrietta’s mother’s home in Carlow; there were numerous friends and relatives to visit in the area and they enjoyed the freedom that rural life allowed. Wandering the fields and the banks of the river Griese, which flowed through the farm, Henry could indulge his passion for collecting herbs. Henrietta travelled regularly to visit relatives in Carlow and the couple became part of the local social life.

Their time at Kilkea was to prove a fertile one, six of their ten children being born in the house over the following seven years. Their first, Gertrude, arrived at the end of 1872. At five o’clock on the morning of 15 February 1874 Henrietta gave birth to the couple’s second child, Ernest Henry. A year later Amy was born and a second son, Frank, was born in 1876. In 1878 the new arrival was Ethel and the last of the Kilkea children, Eleanor, was born in 1879. With six children to raise, Henry and his wife had to face the fact that farming could no longer provide them with a livelihood.

While the famine days of the 1840s were past, there were still regular crop failures due to blight. More importantly, the whole question of land ownership and reform hung over the future of farming in Ireland, and the previous two decades witnessed the cumulative and spreading force of agrarian tension.

Land and its ownership had never been far removed from Irish politics, as the Gavan family would have known. By 1858 the introduction of the Landed Estates (Ireland) Act brought the question of land ownership and control back into the domestic limelight. The 1860 Land Improvements (Ireland) Act had made provision for loans to tenants for the erection of labourers’ cottages but the issue of the ownership of land ran much deeper. The movement towards independence, which had grown out of the 1798 rebellion and the evictions following the Great Famine and led to the abortive Fenian rebellion of 1867, was inseparable from the land question.

The failure of the Fenian Rising had done little to stem the tide of demands for reform and through the 1870s there were regular calls for action by the government in England. In 1878 Michael Davitt – who would go on to found the Land League in October 1879 – was demanding ‘agrarian agitation’. His calls were met with support across the country and tenants were organising themselves in virtually every parish. This political uncertainty, coupled with a periodic downturn in agricultural prices, meant that farming looked less and less promising.

Henry was neither accountant nor politician and, despite the children’s happiness at Kilkea, he and Henrietta concluded that they must move on and find an alternative way of making a living. Medicine seemed to offer the best hope.

The sound of the children’s laughter caught Henry’s attention and he stood to watch them troop across the yard. Again, Ernest was lagging behind, Mr Lag by nickname and Mr Lag by nature. And then, at the sound of passing carriages, the boy was gone, racing along the gravelled path, out through the gate and onto the lane that ran past the house. Henry hurried to follow his son.

‘It’s just a funeral, sir,’ the nurse assured him.

Henry slowed his pace and walked to the gate where he stood watching Ernest. The young boy was trotting after the receding carriages, his short legs working to carry him closer to the hearse. At the end of the lane, where it met the main road between Castledermot and Athy, the funeral cortège picked up speed, leaving Ernest far behind. Only then did he stop running and turn again for home. His father smiled, seeing the boy idling slowly towards him, amused by his son’s fascination with funerals.

Later, when the afternoon was at its hottest, Henry took the children swimming in the nearby river and they repeated the old family joke over and over, laughing boisterously, as they plunged into the clear water.

‘You swim in the Griese and come out dripping!’

While Henry and Henrietta prepared to move to Dublin, life at Kilkea House continued as it had done. The children played in the garden, the scent of the climbing roses, which shadowed the walls of the house, blending with the perfume of the wild honeysuckle that threaded through the field hedges. Passing carts and carriages on the road between Athy and Castledermot drew them to the end of the field that fronted the house. This passing traffic and the occasional trips the family took to the surrounding towns broke the rhythm of their days at home.

On one such family visit, to their cousins at Browne’s Hill in Carlow, Ernest saw, for the first time, a penguin skin. He was fascinated by the pelt, given as a gift to the Brownes. It was unlike anything he had ever seen. He was well used to the moth-eaten fox heads mounted on the walls of many of the houses he visited, and the stuffed remains of tigers and lions brought from India and Africa, while uncommon, were not extraordinary. But this penguin skin was different. Its shape and colour and texture intrigued the young boy and set his imagination racing. There were endless questions about its origins and its habitat. He conjured up stories about where it had come from and how it had reached his corner of the globe. It remained a source of curiosity for a long time and, on subsequent visits, it was the first thing he sought out in the house.

HenriettaShackleton(1845–1926),néeGavan,marriedHenry28February1872. (AthyHeritageCentre)

HenryShackleton(1847–1921),fiftheldestsonofEbenezerandEllenShackleton’stenchildren,andfatherofEHS.Hisvigorousbeardearnedhimthenickname‘Parnell’whenhereturnedtoTrinityCollege.Appropriately,hefavouredHomeRule.(AthyHeritageCentre)

The last thing Ernest did at Kilkea House, before climbing into the carriage that would take him away from his birthplace, was to stand on the fallen tree trunk on the lawn. This had been his ship’s cabin for as long as he could remember, the place where he played on summer afternoons and lay long into the evening, watching the stars appear over Mullaghcreelan Hill, singing his favourite song quietly to himself.

‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star,

how I wonder what you are,

up above the world so high,

like a diamond in the sky.’

Only then did he join the others waiting to leave for a new life in Dublin, where his father would begin his medical studies in Trinity College.

The Shackleton family settled at 35 Marlborough Road in South Dublin and Ernest immediately requisitioned the garden frame as a replacement for the ship’s cabin he had left behind on the lawn at Kilkea House. The house in Marlborough Road was a two-storey over basement, red-bricked dwelling, with gardens back and front, built a decade before the Shackletons moved there and part of the new development of lands close to the suburban village of Donnybrook.

Life in Dublin offered fresh wonders to be explored. For the children, St Stephen’s Green, recently opened to the public, was a place of excursion with their nurse, while the newly opened manual telephone exchange in Dame Street, with its five subscribers, was a topic for comment and discussion over the dining table.

But for Ernest Marlborough Road provided another diversion. A regular procession of passing funerals meant he could more easily indulge his passion for playing chief mourner, watching for the cortèges from the front window and racing down the granite steps to follow the processions.

While Henry pursued medicine at Trinity, the family expanded with the arrival of Clara in 1881, Helen in 1882 and Kathleen in 1884. For Ernest, these additions were little more than distractions, as he had other undertakings to pursue.

The first was the excavation of a large hole in the back garden, which, he told his father, would eventually take him to Australia. The second involved borrowing one of his mother’s rings. Having liberated it from her room he buried it in the garden and arranged for his nurse to be present when he unearthed the unexpected treasure, glorying in her surprise and delight.

35 Marlborough Road, Dublin, home 1880–84 to Henry and Henrietta, their six children and three more daughters born there. A commemorative plaque was unveiled by EHS’s granddaughter, Alexandra Shackleton, in May 2000.

Evenings were spent reading and sketching. Ernest had had some lessons in sketching and, even as a child, was keen to develop this talent. The Jules Verne stories in the Boys’OwnPaper were Ernest’s favourite reading material. Indeed, as a quiet child, he often seemed most happy with his own company, not that solitary moments were frequent in a house where there were now nine children.

AberdeenHouse,12WestHill(nowWestwoodRoad),Sydenham,wheretheShackletonsmovedinJune1885,whenHenrystartedhispracticeasalocaldoctorforthenextthirty-twoyears.

EHSagedeleven,whenhewasapupilatFirLodgePreparatorySchool,Sydenham,London.

As at Kilkea, mealtimes regularly found the family playing a favourite game of capping quotations, with Henry giving the children a fragment which they would try to complete. Ernest was particularly adept at this, Tennyson being his favourite source.

In 1884 Henry qualified, with distinction, taking an M.B. and M.D. from Trinity College. Again, it was decision time. Henry and his wife discussed the possibilities of establishing a practice in Dublin but opted for the greater opportunities offered by London.

In December 1884 Henry, Henrietta and their nine children sailed on the Banshee from Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire) across the Irish Sea to Holyhead, and travelled from there to London.

The Shackletons’ first home in London was in South Croydon. Despite Henry’s best attempts, he found it impossible to establish a successful practice there and, the year after his arrival in England, he moved the family to Aberdeen House, 12 West Hill (now Westwood Road) in Sydenham. Two years later, in January 1887, Henrietta gave birth to the couple’s tenth child, Gladys.

Life as a doctor was more rewarding for Henry in Sydenham. Henrietta, however, worn out by the birth of ten children, fell victim to a mysterious illness which left her without any energy. It was a sickness that Henry might have come across in Kilkea, where the locals would have described it as themionaerach, a disease that wouldn’t kill but debilitates the sufferer with little or no energy. Henrietta, so long the vital and good-humoured heart of the family, withdrew to her sick-room and rarely left it until her death in September 1926.

Despite their mother’s illness, the children set about establishing new lives for themselves and were enrolled in schools in Sydenham. Ernest began attending Fir Lodge Preparatory School and rapidly acquired a new nickname, Micky, which also stuck at home. His new schoolmates found his Irish accent and manner an easy target for their sarcastic jibes. He had arrived a quiet and pacific boy but in his early days at the school he obviously decided it was time for a change. As a result he quickly acquired the reputation of ‘a brave little fellow, ready to fight the universe and all therein’. Among the friends he made at school the closest was Maurice Sale-Barker. They played football together and mercilessly taunted the younger Shackleton sisters.

Meanwhile, Henry was busy establishing his medical practice. The difficulty of bringing up a large family, pursuing a career in medicine and looking after an ailing wife did nothing to dent his enthusiasm for work. Among his patients was Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx. Eleanor lived just around the corner from the Shackletons, in Jew’s Walk, and it was to her house that Henry was called one afternoon in March 1898. Arriving quickly, he found that, as a reaction to the end of a love affair, she had taken an overdose of prussic acid and died before he could be of any help.

However, most of Henry’s cases were more mundane. He was hardworking, popular with his patients and as a result built up a thriving practice which continued in Sydenham for thirty-two years. He was handicapped, however, by increasing deafness, and as early as 1906 began to look to Ernest for financial support.

In 1887 Ernest was enrolled at Dulwich College as a day-boarder. The college had been founded in 1618 and, while not in the first rank of public schools, had a substantial reputation for producing businessmen and civil servants, the backbone of the middle class. It drew its boys from the locality and from families that were solvent rather than wealthy. In later years it would become known as the almamater of P.G. Wodehouse and Raymond Chandler.

While Ernest was extremely accomplished at boxing and gym, and did well at cricket and football, his academic achievements at Dulwich were marked by a succession of reports through which ran the common thread that he could apply himself more, work much harder and do a great deal better. John Quiller Rowett (later the main sponsor of Shackleton’s final Quest expedition) used to walk with him to school and wrote: ‘He was always full of life and jokes, but was never very fond of lessons … I had a friend who knew German very well, and I used to get hints from him which I passed on to Shackleton.’

Boredom rather than lack of ability was Ernest’s chief problem. He excelled at the things he enjoyed and went to great lengths to collect foreign stamps, for instance. But he found little in the way of inspiration in the droning of his masters.

However his interest in the sea and all things maritime was growing. He regularly spent schooldays playing truant with friends near the local railway line. There the boys would cook over an open fire, smoke endless cigarettes and listen to Ernest reading stories of seafaring and adventure. Their campfire talk turned, time and again, to the exciting prospect of running away and joining a ship. Eventually, words led to action and the friends made the journey to London Bridge to enlist on a ship. They queued for an interview with the Chief Steward, who took one look at the motley crew and sent them packing.