Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

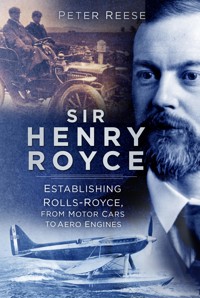

It's hard to imagine a history of British engineering without Rolls-Royce: there would be no Silver Ghost, no Merlin for the Spitfire, no Alcock and Brown. Rolls-Royce is one of the most recognisable brands in the world. But what of the man who designed them? The youngest of five children, Frederick Henry Royce was born into almost Dickensian circumstances: the family business failed by the time he was 4, his father died in a Greenwich poorhouse when he was 9, and he only managed two fragmented years of formal schooling. But he made all of it count. In Sir Henry Royce: Establishing Rolls-Royce, from Motor Cars to Aero Engines, acclaimed aeronautical historian Peter Reese explores the life of an almost forgotten genius, from his humble beginnings to his greatest achievements. Impeccably researched and featuring almost 100 illustrations, this is the remarkable story of British success on a global stage.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The thirteenth Silver Ghost in a lovely English setting near its birthplace. (Rolls-Royce)

To Dr Joanne Shannon,with thanks

Cover illustrations all courtesy of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust

Front: (from top) The first Royce car on the road; Henry Royce in 1907; 1931 Supermarine S6B, outright winner of the Schneider Trophy.

Back: A connecting rod, big ends and piston assembly for the Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Peter Reese, 2022

The right of Peter Reese to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9081 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Contents

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Preface

PART 1: EMERGENT ENGINEER

1 Early Struggles

2 Royce and Claremont – Branching Out

3 Royce and His Motor Car

PART 2: OF WHEELS AND WINGS

4 Rolls and Royce

5 Johnson, Royce and the Silver Ghost

6 The Silver Ghost in Peace and War

7 Royce’s Move to Aero Engines

PART 3: POST-WAR CHALLENGES

8 The 1920s: Automobiles versus Aero Engines

9 Royce’s Aero Engine and the Schneider Trophy Contest of 1929

PART 4: MASTER DESIGNER

10 Automobiles – Preserving the Marque

11 Winning the Schneider Trophy Contest of 1931

12 Royce: The Man and His Achievements

Notes

Select Bibliography

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Further detailed consideration of the renowned engineer Sir Henry Royce is surely long overdue.

It is some eighty-five years since Sir Max Pemberton’s original biography, which he himself called a plain story of the man and his most able associates, notably C.S. Rolls and Claude Johnson, whom Pemberton regarded as being jointly responsible with Royce for the Silver Ghost, his famous motor car, and for the Rolls-Royce Company.

Pemberton spent time considering the lives of Rolls and Johnson (through Johnson’s autobiography) as well as Royce, and made no attempt whatsoever to deal with what he referred to as ‘the vast technicalities of Royce’s engineering achievements’.

He sought information on Royce from some of his closest entourage, including Royce’s medical friend Dr Campbell Thomson; his wife Lady Royce; his solicitor Mr G.H.R. Tildesley; another close friend, Mr G.R.N. Minchin; racing driver Captain Percy Northey; Mr A.F. Sidgreaves, Rolls-Royce’s one-time Managing Director; and Royce’s faithful nurse Ethel Aubin.

Reliance on the knowledge of such individuals was partly due to the fact that Royce – the most private of men – left no personal papers, a situation compounded by the decision made by Rolls-Royce during the Second World War to consign most of its historical documents to pulping during a campaign to accumulate such material.

My decision to write a second biography after so long was made in the knowledge that I could no longer consult people with personal knowledge of him, although fortunately, in the period between Royce’s death and the present, a number of books and articles have been published on Rolls-Royce concerns – many through the auspices of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. These include reminiscences by such individuals as Donald Bastow, Donald Eyre and H. Massac Buist. Other books that have proved of especial value from a comprehensive list are as follows:

H. Nockolds, The Magic of a Name,

R. Schlaifer and S.D. Heron, The Development of Aircraft Engines and Fuels,

Derek S. Taulbut, Eagle: Henry Royce’s First Aero-Engine,

Peter Pugh, The Magic of a Name: The Rolls-Royce Story, The First Forty Years,

W.A. Robotham, Silver Ghosts and Silver Dawn,

Anthony Bird and Ian Hallows, The Rolls-Royce Motor Car,

Ralph Barker, The Schneider Trophy Races,

George Purvis Bulman, An Account of Partnership: Industry, Government and the Aero Engine: The Memoirs of George Purvis Bulman,

Ian Lloyd, Rolls-Royce: The Growth of a Firm and Rolls-Royce: The Years of Endeavour.

As with any book, I owe immense debts to both organisations and individuals. I have been most fortunate in obtaining a copy of the large number of letters and instructions which Henry Royce sent to Derby from 1914 to 1916 during the construction of his first aero-engine. (For this I am indebted to John Baker, Business Manager of the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation, for having them scanned on my behalf.) These have helped me undertake a first-hand study of his methods and high technical accomplishments.

I am also much indebted to the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust and its Chief Executive, Neil Chattle, and Sandra Freeman, Editor of The Journal of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, for supplying me with a quite magnificent selection of pictures at such a uniquely difficult time.

With regard to learned institutions, the National Aerospace Library at Farnborough has once again played a pivotal role with its superb aviation collection. Librarians Brian Riddle and Tony Pilmer have, day in and day out, fielded my many queries, with rare thoroughness and unfailing courtesy that made it a pleasure to work there. The British Library’s facilities were as magnificent as ever, especially as I was able to beat the Covid-19 shutdown. I also acknowledge the help given by the Prince Consort’s Library at Aldershot with its librarian Diane Payne and the access to the aeronautical collection afforded me by the Hampshire Public lending Library at Farnborough.

I fully acknowledge invaluable support from The History Press without which the book would not appear, particularly Commissioning Editor Amy Rigg and Project Editor Jezz Palmer.

With regard to individuals, I am most grateful to Rob Cooke for his painstaking reading of the book’s first draft and his valued amendments; to Mike Stanberry for his valued professional assessment and comments on it; to Paul Vickers for outstanding help with taking, identifying and processing the book’s images and inspiration with its title; to Shally Lopes for her indefatigable and accurate work on the computer in producing repeated versions of the script; to Tony Pilmer for so many further significant contributions and for compiling an excellent index; to Brian Riddle for his historical assessment; to my friend Tony Hodgson for chasing up sources for the book; to Dave Evans for personal support to Barbara and myself; to my son, Martin, for his help when visiting the British Library; to Arthur Webb for his patience, humour and authoritative responses to my endless queries about aviation matters; to Rob Perry for the loan of fine books from his own collection; to my good friends among the Aerospace Library’s volunteers, Katrina Sudell, Beryl James and David Potter for their support on many occasions; and to my long-standing friends at FAST (Farnborough Air Sciences Trust), notably Richard Gardner, Veronica Graham-Green, Graham Rood and Anne and David Wilson with particular thanks to Paul and Marie Collins for their continuing kindness and their amazing support at lecture times.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders but, in the event of any omission please contact me, care of the publishers.

Finally, as on so many occasions over the years, I thank my dear wife, Barbara, for her inestimable and lovingly given encouragement which through the trauma of Covid-19 has meant repeated feeding and watering of a pre-occupied partner and responding again and again to his partly formed ideas and early drafts.

As ever, any shortcomings are the author’s responsibility.

Peter Reese,

Ash Vale

Preface

In 1866 a small boy, yet to reach his fourth birthday, stood on a hummock in a Lincolnshire field with his eyes upturned to the sky. His appointed task to assist with his family’s hard-pressed budget was to wave his little arms to deter birds from eating corn in the field adjoining his home, for which service the farmer paid his diminutive bird scarer the sum of 6d a week (2½ new pence).

For so young a child the task was immense. The field stretched in all directions and his only accompaniment was the sounds of horse-drawn traffic moving along the nearby lane, while the opportunity to see a frail aircraft disputing the illimitable fenland skies was still half a lifetime away. The advent of both automobiles and aircraft would depend on liquid petroleum engines fired by electric ignition, technology that would not be developed until the later years of the nineteenth century.

Our young bird scarer’s subsequent education was scant with just two years’ formal schooling, but although he suffered ill health during his last twenty years, he was responsible for notable advances in both British automobile and aero engines. From 1906 onwards came his superlative 40/50hp Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost – long considered the best car in the world – followed in 1915 by his Eagle aero engine, which offered unrivalled levels of power and reliability for British pilots during the First World War.

Over the next two decades his contributions would continue undiminished with other first-rate cars to succeed the Silver Ghost, although his premier advances would be in aero engines. In 1926 he produced the Kestrel, a revolutionary compact engine, whose twelve cylinders were set in a single block of aluminium alloy. This was the forerunner of the ‘R’ engine that in 1929 and 1931 won the final two Schneider Trophy air speed contests for Britain, during which it achieved by far the highest power-to-weight ratio of any engine so far. Its development in turn led to the brilliant V12 water-cooled engine, which became known as the Merlin, that performed spectacularly in virtually every notable British aircraft during the Second World War.

In 1933, at the age of 70, Henry Royce succumbed to the ill health that had dogged him for so much of a career spent in ‘the steadfast pursuit and attainment of perfection’.1 He had continued designing until the very eve of his death.

This book examines the glorious harvest of a premier British engineer whose achievements owed so much to his prevailing drive, uncompromising standards and extraordinary work ethic, although, as we discover, he could never have succeeded without the support of other able folk, who helped him both create and sustain his superlative contributions.

1

Early Struggles

Like Henry Royce, a proportion of Britain’s most eminent engineers came from humble, if not unpromising, backgrounds and commenced their working lives at impossibly early ages.

The great George Stephenson (1781–1848), whose father was the fireman of the colliery engine at Wylam near Newcastle upon Tyne, began his working life as a boy herding cows and leading horses at the plough. He then became a ‘picker’, clearing out stones from coal, before driving the horses working the gin at Black Callerton colliery.1 At 14 he was appointed assistant fireman to his father at nearby Derby Colliery before becoming an engineman, from which point he embarked on his astounding career concerned with steam railways. Even so, he was 18 before he learned to read and write.

Likewise, entrepreneur Edward (Ted) Hillman (1889–1934) was involved in both motoring and aviation. Following the sketchiest education, at 12 years of age he enlisted as a drummer boy in the British Army. By the outbreak of the First World War he had risen to the rank of Warrant Officer and his military career seemed assured, but in 1914 he was seriously wounded during the British Army’s retreat from Mons.

As a consequence, he was invalided out of the Army with a marked limp and a small gratuity, which he used to purchase a taxi. Such was his diligence and thrift that he soon bought his first motor coach, which by 1928 he had turned into a fleet of some 300. In 1934 his plans were thwarted when his coaches were compulsorily purchased as part of the Government’s plans to rationalise public transport. Undaunted, Hillman used the proceeds to set up the original no-frills airline in the later tradition of Freddie Laker and Ryanair.2

Whatever the triumphs of such men against the odds, their early struggles could never exceed those of Henry Royce, about which, according to his early biographer, Sir Max Pemberton, he loathed to speak,3 although Donald Bastow, who subsequently enjoyed a close working relationship with him in his final years, had no doubts about his unquestioned pride in his family’s previous achievements. Henry’s birth certificate shows that, in fact, he was born at Alwalton on 27 March 1863 to James Royce, a miller, and his wife Mary. The birth was registered at Peterborough, Huntingdonshire’s county town.

As a result of Royce’s subsequent enquiries, he came to believe he was descended from ‘a Welsh master bowman called Rhys or Ryce’4 who reputedly fought with Henry Tudor at Bosworth Field, for which he received an appropriate reward. Whatever the veracity of the legendary bowman’s feats, succeeding generations of the Royce family undoubtedly prospered, and we are indebted to Donald Bastow for the following Family Tree.

Henry Royce’s birth certificate. (Author’s collection)

Royce Family Tree

As Bastow points out, while the family tree incorporates only the essentials, the first entry of Anne Royce, a widow, was from the Elizabethan times and it shows a line of successful farmers and millers, some of whom acted as churchwardens. Henry’s grandfather, Henry William Royce, was certainly a miller/engineer who pioneered the installation of steam power in water mills.

Some of the family crossed the Atlantic. Following the emigration of Robert Royce – a shoemaker – to Connecticut during the reign of Charles II, two of Robert’s sons, Nehemiah and Nathaniel, became planters at Wallingford, Connecticut. Nehemiah married a member of the Morgan family that later became famous for its banking activities, while Nathaniel built a fine house at Wallingford. This was commonly called ‘The Washington Elm House’ due to a huge elm tree standing at its front, under whose wide branches General Washington had said farewell to the townspeople before going to war against the British.5

Another branch of the family under William Cooper and his wife Elizabeth (née Royce) was one of the first to be established in the West Toronto district of Canada, to where during the nineteenth century Royce’s grandfather Henry William Royce – who, during a long adventurous life, married three times – would choose to emigrate.

Henry William Royce, Sir Henry’s grandfather. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

It is feasible that he would have played a major role in his grandson’s affairs had he not decided in 1866 – when Henry was only 3 – to join his cousin in Canada, where George Cooper and his brother William had been born some half a century before. William subsequently died from blood poisoning following a scratch from a bear that, according to legend, was kept to entertain customers at his public house, but George bought the 400-acre plot that they had earlier decided to acquire jointly and after an interval married his brother’s widow. Timber from the plot was sold to help buy a farm. This prospered and Henry William – along with most of his family – joined George on his farm.

Later, a significant connection would occur between the Rolls-Royce Company and another member of the family who had emigrated to America under the leadership of Royce’s grandfather. This was professional engineer James Charles Royce (Henry’s cousin). When in 1911 Henry Royce became so seriously ill that he was likely to die, Claude Johnson attempted to safeguard the Royce connection by offering James Charles work at Derby. Henry’s recovery made this much less important but during the First World War, James Charles Royce became the representative engineer for Rolls-Royce in the US and Canada and was heavily involved in the campaign for the Eagle engine to be made in the US under licence.6

As for the Royce family’s exodus from England in 1866, the only two family members who stayed behind in Britain were in fact Henry’s father, James, whose business was failing and who by now was not strong enough to make the journey across the Atlantic, and Henry’s great uncle, John Charles Royce, who would subsequently marry and have six children in England.

Royce’s Canadian relatives. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

Whatever the positive achievements of many of Royce’s ancestors, his father enjoyed no comparable successes, being referred to by Pemberton as ‘bustling, hearty, florid but wholly unreliable’.7 Royce himself devastatingly described his father as unsteady but clever, someone lacking the determination to apply himself single-mindedly to a task.8

Mindful of the Royce family’s accomplishments, Pemberton sought other reasons for James’ failure. Initially, he suspected that he might have been ‘a little too fond of the bottle’ but later discovered he had contracted Hodgkin’s disease, which in its later stages – together with behavioural changes – was generally accompanied by anaemia and intermittent fevers, although this in no way explained his earlier failings. In fact, James followed family tradition with his agricultural training before he moved on to milling and in 1852, rented the mill at Castor, Northamptonshire.9 In that year he appeared to make a good marriage to Mary King, whose father had a large-scale farm at Luffenham. They had three daughters, Emily (born in 1853), Fanny Elizabeth (born in 1854) and Mary Anne (born in 1856), followed by James Allen (born in 1857) and finally, more than five years later, their last child, Frederick Henry. By then James’ business affairs were already taking a serious downturn following an earlier move from the family mill at Castor to another at Alwalton, in nearby Huntingdonshire, for which he took out a lease from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. This had both steam and water power, with the former almost certainly installed by James.

James Royce, Sir Henry’s father, with Sir Henry’s sister Emily. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

Whatever the circumstances, by 1863 James had been compelled to mortgage his lease to the London Flour Company, but in 1867, when Henry Royce was four, the business failed completely. With most of the immediate family in Canada, no help could be expected from that quarter and there is no record of aid coming from Mary’s family – with the notable exception of her sister, Miss Betsy King, whose assistance would come considerably later.

As a consequence, they faced the heartbreaking prospect of dividing the family. It was decided that the three girls, the eldest of whom was already 14, should be boarded for a time at Alwalton’s Inn with a Mrs Clarke, while their mother sought employment as a housekeeper with private families, with most of her modest earnings likely to have been used to help with their keep.

As for the boys, it was agreed that they should accompany their father to London where, due to his knowledge of steam power, he had succeeded in finding work with the recently established London Steam Flour Company at its newly founded mill in Southwark.

Whatever James’ employment, with his disposition and fast-deteriorating health there could be no happy outcome and when Royce turned 9, his father expired in a public poorhouse at Greenwich when just 41 years of age.

Despite the meagre details of Royce’s early years, we have the strong impression not only of physical privation but of him being largely left to his own devices in a world ‘which had but little use for him’.10 A written account by L.F.R. Ramsay, for instance, maintained that due to his relative isolation as a child Royce was late to walk and speak and did not utter his first word until he was 4.11 Whether Ramsay was correct or not, Royce’s early family commission as a human scarecrow was hardly likely to help him develop social skills and during his father’s final illness, money was bound to be short, although his mother Mary found work closer to him in order to help with food and shelter.

There was never any question of Henry being able to live with her, although he apparently stayed for a while at the London address of an old couple who had been with his father at Alwalton. When one of them died, this arrangement ended and his subsequent memories of lodgings were predominantly of hunger and cold. Many years later he remarked that, in one, ‘My food for the day was often two thick slices of bread soaked in milk’12 and on a particular evening, faced with the prospect of an empty, cold house, he apparently chose the greater comfort of an outside dog kennel complete with its canine occupant. (His affection for dogs would remain with him throughout his life.)

As for schooling, by the time of his father’s death he had spent just one year at the Croydon British School. Between the ages of 9 and 14, Royce needed all his innate resolve and pronounced work ethic to survive the harsh environment of late Victorian London with its unforgiving attitude towards the aspiring poor. His mother was able to give only limited help, although there was a great-aunt Catherine on his mother’s side who lived at Fletton near Peterborough whom he was accustomed to visit for some days at a time. At 10 he began selling newspapers for W.H. Smith at Clapton and Bishopsgate railway stations and as a result was able to attend school for a further year from 11 to 12 years of age, but in 1876, when he reached 13, he became a full-time telegraph boy. He delivered telegrams, where his favourable attitude and appearance had him selected to take them to homes in prosperous Mayfair. Even so, such work was no bed of roses. As he explained, ‘I had no regular wages … They believed in payment by results in the Post Office in those days. Telegrams cost only six pence, as you know, and the boy who delivered them got a half penny, irrespective of distance, you didn’t get much in a day.’13

Against the odds, at 14 Royce’s life changed dramatically for the better. During one of his short holidays at Fletton, his great-aunt must have realised that work as a messenger was quite inadequate for him. She thereupon went to the Great Northern Railway Works at nearby Peterborough, where for the sum of ‘£20 per annum’14 she arranged for him to become an indentured apprentice with hopes of becoming a skilled engineering worker. This was the equivalent of some £2,896 at today’s valuation (2020) and given her limited capital, it represented a massively generous initiative. Royce’s belated good fortune was further helped by the nature of his Peterborough lodgings with a Mr Yarrow and his family, including his son Havelock, who also worked at the railway works as an apprentice.

Havelock recalled being sent in 1878 to the village of Fletton to bring Fred – as Royce was always known at that time – to their house at Peterborough. ‘He was a very earnest lad at that time some six years younger than myself, as interested as he could be in all that concerned the great machinery in Mr. Rouse’s charge.’15 In fact, Havelock proved far from generous about their young lodger’s practical skills and he was convinced about the family’s crucial contributions to Royce’s subsequent successes.‘In the course of time he began to make himself quite a good mechanic, though I would not say he was over-quick at the mastery of tools. He learned by degrees, but what he learned he learned thoroughly.’16

Frederick Henry Royce as an apprentice with the Great Northern Railway, Peterborough. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

Whatever the Yarrow family’s contribution, Havelock did acknowledge Royce’s rare intellectual appetite and industry:

He was a very quiet lad at that time and rarely went out at night. You couldn’t keep him away from books. Although he had hardly any schooling he managed to teach himself quite a lot about electricity and algebra and something also about foreign languages … But electricity was the thing that interested him most. Not very much was known about electric currents in those days and everything was in a primitive stage, batteries and generators particularly, although electric light was beginning to be heard of and some of the companies, I believe, were actually using arc lights for the illuminations of their sidings …17

Whatever additional knowledge Royce acquired through long hours of study after a full day in the workshop and continuing to sell newspapers, Havelock had absolutely no doubt about his father’s contribution to his mechanical skills.

My father, I should let you know, had quite a nice little workshop out in our back garden at Peterborough. He had a 6 inch lathe there and a carpenter’s bench, a shaping machine and grindstone and it was always his idea to do every bit of work that had to be done about the house. He was a clever workman and he was very interested in Fred’s first endeavours to use the tools. I think it was the instruction he received with us that made him a master at the lathe and taught him a lot about fitting and filing. When he left the works he was a very capable mechanic, and Mr. Rouse had come to think highly of him, in fact he carried away testimonials which should have got new employment anywhere.18

Havelock Yarrow’s reference to Royce’s testimonials was timely because in November 1880, after just three years’ apprenticeship, his great-aunt’s money was needed for another emergency and he had to leave. However glowing his testimonials at this time, British industry was suffering from one of its periodic depressions and many firms were laying off men, including fully trained ones.

His hunt for work involved him walking from Peterborough to Leeds to join his middle sister Fanny Elizabeth and her husband, where Royce’s mother was by this time an additional member of the household (whom the 1881 census listed as being 52 years of age).

Although not fully qualified, within a fortnight Royce had found work – if at the parsimonious rate of 11s for a fifty-four-hour week – with toolmakers Greenwood and Batley, who had landed a contract with the Italian arsenal then being built to help equip the Italian Army.

At Greenwood and Batley, Royce adopted the practice of working many days from 6 a.m. till 10 p.m. and all through Friday night in a likely attempt to save some money, which after paying his board was not likely to have been that easy. In spite of such long hours, he continued to learn as much as he could about electrics and other subjects, most likely at evening classes following his ‘short’ days.

Within a year Royce returned to North London with the aim of using his knowledge of electrics to join what was unquestionably an aspiring industry. In 1881, when still only 18 years of age, and in spite of having no practical experience, he was accepted by the Electric Lighting and Power Generating Company as a tester at 22s a week (double his previous earnings). The company went on to acquire patents on incandescent lamps from the American inventor Hiram S. Maxim and on arc lamps from Edward Weston (which had earlier been used at the Peterborough Railway Works) and it accordingly changed its name to the Maxim-Weston Company. By March 1883, it had spent no less than £14,000 on patents compared with £2,000 on plant and £20,000 on stock and work in progress.19 The results were only too predictable. In May 1884 it registered a loss of £32,000 and by 1888 the firm was in liquidation.

For its new employee such concerns were not yet a worry and he took lodgings in Kentish Town before rapidly enlisting for a course of evening studies at the City and Guilds Institute for the Advancement of Technical Education at Finsbury under legendary Professor William E. Ayrton, whom he apparently impressed. This course of study might actually have been suggested to Royce by Hiram Maxim or some of the eminent specialists associated with him,20 although he would doubtless have needed little persuasion to take it up. Royce’s work must have satisfied his employers for in late 1882 they posted him from London to Liverpool, where at the age of 19 he was appointed Chief Electrician of their subsidiary, the Lancashire Maxim-Weston Electric Company Limited at Peter’s Lane Liverpool, which, in fact, was seriously undercapitalised.

In his biography, Pemberton related how the company was committed to lighting a number of streets and theatres in Liverpool, where Royce made significant investigations into the three-wire system of conducting electricity, sparkless commutation and the drum-wound armature for continuous-current dynamos. He confessed to Pemberton that at this time he used to wait in his office in as critical a state of suspense as those people in the theatre who were looking for the death of the villain or the salvation of the heroine. ‘From time to time I sent a small boy round to see if the lights were still burning. Happily the tale of casualties was slight and in the main we managed to light their darkness. But it was the devil of a business.’21

Royce was not to enjoy such uncertain successes for long. Although on 30 October 1883, Liverpool Council accepted his company’s tender for lighting the streets and theatres – and continuous lighting had actually commenced on 24 March 1884 – just two months later, on 24 May 1884, everything was brought to an end. The Lancashire Maxim-Weston Electric Company was liquidated and it was announced that ‘from and after the 24 instant (May) the Company will cease to light the streets at present being lit by their Weston System of electric light’.22

Council proceedings of the City of Liverpool, 25 March 1884. (Liverpool Central Library and Archives)

Due to its early successes, the parent company decided it was worth buying out their insolvent subsidiary. In May 1884 their offer was accepted, following which fresh negotiations were opened with Liverpool City Council for new lighting schemes where the Town Clerk ‘expressed himself very favourably with respect to the electrician and engineer’.

In the event Royce found himself in a most difficult situation. Despite the Town Clerk’s endorsement of his work, final agreement on the new contract was bound to take time, during which he would be unpaid, and he had by now apparently received encouragement from some of his colleagues about setting up on his own. The extent of his dilemma about whether he should stay with the reborn company or take the massive step of striking out on his own with his hard-earned but diminutive capital of just £20 needs no emphasis.

In favour of the latter course, he had recently become 21 – the age of majority and a significant landmark at the time. Another positive in going it alone was that although he lacked education, he had already discovered whatever information he could about electrics, supplemented by some theoretical knowledge acquired at evening classes. In fact, he later attributed his phenomenal memory to his night-school education (which was uncertain in duration and for which he had sacrificed much of his limited leisure time) that made it imperative – ‘I should never forget anything worth remembering.’23 However limited such knowledge, he had already demonstrated his ability as a practising electrical engineer.

Most important of all was his inherent sense of independence and self-assurance; he was happy in himself and never doubted his abilities. Over 6ft tall with a gaze that betokened his determination, already tempered by adversity and buoyed by his recent achievements, he drew up plans to make novel products of his own design.

To further his ambitions, Royce decided to leave Liverpool for Manchester. He was likely to have chosen Manchester over London or Liverpool, cities also well known to him, because its basic costs appeared more favourable to set up a small backstreet company. There he would shortly be joined by another young man – Ernest Claremont – in what would be a joint enterprise. However much he realised he needed a partner, it was a further measure of Royce’s confidence that he decided to put the embryonic business in his own name.24

His early deprivations and the insecurity of working for firms that were either not well funded or unprepared to pay just rates for skilled and conscientious working men weighed on him. He sought the opportunity to see how his own skills and ferocious working practices could make commercial sense, however modest his first workplace and joint capital resources. Despite his high ambitions, dedication and rare engineering acumen, Royce could hardly have anticipated the monumental struggles the two would meet with over the next twenty years, nor when, after they were joined by a young, blue-blooded motor-car salesman, their products would come to symbolise a new standard of excellence not only for British but for world engineering. In the firm’s early stages such progress must have seemed beyond belief.

2

Royce and Claremont – Branching Out

F.H. Royce and Company began its small-scale activities in Blake Street, Manchester, an unprepossessing area containing stables, a Temperance Hotel and a cabinetmaker’s workshop. The Poor Rate Records for 1885 refer to F.H. Royce and Co. sharing premises with a salesman, W. Sergeant, at an annual rate of £17.1 Royce would not have been able to pay his rent in advance and in spite of his ability to live sparely, his scant capital would never have been enough to buy the materials, along with the necessary machinery and tools, for an industrial undertaking. He required a partner and Ernest Claremont almost certainly joined him during the firm’s first six months, bringing a further capital sum of £50, which he was likely to have borrowed from his father.

Ernest Alexander Claremont. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

Although their joint application some twelve years later (in October 1897) for membership of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers confirmed their continuing partnership, it also demonstrated that after more than a decade, the company stayed firmly in Royce’s name. Even so, in Claremont, Royce found the first among a succession of colleagues who not only recognised his exceptional attributes but without whom he could never have fulfilled his ambitions.

Royce’s application for membership of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. (Institution of Mechanical Engineers)

Where Royce and Claremont met is uncertain, although author Paul Tritton believed it was likely to have been in London, possibly when attending Professor William Ayrton’s evening classes in Finsbury.2

Like his other relationships, that with Claremont would be long-standing and it continued, in fact, until Claremont’s death on 4 April 1922.

Due to their different social backgrounds, it appeared an unlikely association, for as the son of a surgeon Claremont was born into an affluent and large family of intellectually and artistically gifted individuals.3 He was educated privately before attending University College London, although he did not graduate for during the second year of his degree course he took up an apprenticeship with the Anglo-American Brush Electric Light Corporation in London, where he was likely to have worked with the firm on lamps or dynamos. Like Royce he failed to complete his full apprenticeship, which in Claremont’s case was the outcome of a major dispute with his foreman.

Although Royce and Claremont shared a common enthusiasm for electric lighting and commerce, they were very different individuals. Claremont was small and dapper with a wide number of outside interests compared with the tall undeviating Royce. Claremont prided himself on his deportment and fitness while Royce showed little interest in his appearance or even his food when he was intent on their latest engineering assignment. Claremont later became an officer in the Yeomanry with its demanding military commitments and high standards of horsemanship, although during the firm’s initial development he came close to matching Royce’s fearsome dedication.

By necessity their early priorities were directed towards acquiring equipment and materials rather than meeting their personal needs, and being unable to afford lodgings they shared a room over the works where they both ate and slept (in hammocks). Their staple food was sandwiches and any cooking – often of sausages – was carried out in an enamelling oven, which Claremont held responsible for their later digestive problems. Apparently their main diversion from the grinding regimen of work was a wild card game called ‘grab’ that culminated into a form of all-in wrestling, which often ended with them rolling round the floor in their boiler suits.

With such limited resources, their early output was bound to be modest. In fact, Royce’s first successful product was a domestic electric bell consisting of a bell and push, with wire and a Le Clanché cell battery, that apparently sold for just 7s 6d. Royce drew up the plans, made the simple jigs required and set about producing it while Claremont was responsible for everything else: sales, contracts, payments and deliveries – although if needed he would also help at the bench.4

Their firm at this time was described as electrical and mechanical engineers for, to make ends meet, they apparently accepted any engineering task placed before them, including the repair of sewing machines. In the electrical field it manufactured lamps, filaments (for Edison–Swan) and holders for incandescent bulbs, with the early employees remembering broken glass lying everywhere.

Throughout the first three years, things remained on a knife edge as the partners took on their first employees. They started by engaging a freelance worker with sales experience, Thomas Weston Searle (whose employment could easily be terminated), and then six young women, before in 1887 ‘Old Tom’ Jones, their first journeyman, arrived.5 He received the doubtful honour of being allocated a vice next to the irascible perfectionist Royce. The young women assembled the bells and the filaments for light sockets, while the rest undertook all the other commitments.

Even so, with his unmatched ability and drive for perfection, no one else approached Royce’s work rate. It was customary at this time for him to frequently work through the night and when the others came in the next morning they would find him catnapping at his bench. As he commented in later years to the News Chronicle:

For many years I worked hard to keep the company going through its very difficult days of pioneering, personally working on Saturday afternoons when men did not want to work and I remember many times our position was so precarious that it seemed hopeless to continue. Then owing to the great demand for the lighting dynamos we made for cotton mills, ships, and other lighting plants, we enjoyed a period of prosperity.6

Along with his bench work, Royce was responsible for designing all the firm’s products, including the dynamos made to his own specification and his first patent, the bayonet-cap lamp socket, which was granted on 24 July 1897. His dynamos were superlative and he was subsequently to acknowledge his own contributions:

Blake Street premises. (P.H. Vickers)

The last photo of the doorway of 1A Cooke Street. (Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust)

In dynamo work, in spite of insufficient ordinary and technical education, I managed to conceive the importance of sparkless commutation, the superiority of the drum-wound armature for continuous current dynamos and [the company] became famous for continuous current dynamos which had sparkless commutation in the days before carbon brushes. While at Liverpool from 1882 to 1883, I conceived the value of the three-wire system of conduction in efficiency and economy of distribution of electricity …7

Royce was, however, not alone in his appreciation of the three-wire system for in 1882 it had also been developed by Edison.

Given their leaders’ vision and skills, and the loyal support of their small workforce, it seemed only a matter of time before progress would be made. Sure enough, at some time before 1888 the partners felt able to take lodgings with John and Elizabeth Pollard at 24 Talbot Street, Moss Side, although there was no question of them easing the throttle, for they were accustomed to continue discussing current problems as they walked together between their lodgings and Blake Street after finishing work.8