Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

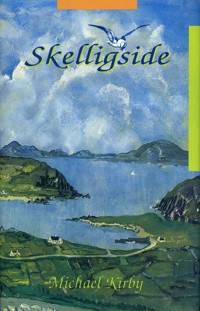

This is the remarkable folk autobiography of a small famer, fisherman and poet from from the South Iveragh peninsula of Co. Kerry, part of Ireland's western sea-board, a region bounded by mountains and unique inits cultural inheritance. Kirby's writing combines description with narrative, anecdote and poetry, and gives a vivid pen-picture of the locality of Ballinskelligs – its famed island and birds, its fishing, husbandry, crafts, old customes, migrant experience, local history and folklore – in testimony to a vanishing way of life. Kirby's voice – akin to that of the Blasket writers – is one of the last authentic expressions of a Gaelic tradition, imaginatively fusing worlds of flesh and spirit. He writesd with all the artlessness and freshness of a man departing from his native language. By gathering one small area into the net of memory, personal and inherited, Michael Kirby celebrates and commemorates the place where he was born.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 236

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1989

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Skelligside

Michael Kirby

for Nancy and Max

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

I My Own Place

An Early Schooling

The Riches of the Sea

The Skelligs

II Seed-Time and Harvest

Kelp and Potatoes

Growing Flax

Cutting the Turf

Oats and Hay

The Gentleman at Home

III Making and Mending

Building and Thatching

The Basket-Weaver

The Cooper

The Blacksmith

Tailors

The Village Cobbler

IV The Living Voice

Our House

The Journeyworkers

Ghosts

Some Poets and a Storyteller

The Island of the Fair Women

An Elizabethan Tale

The Red-Haired Friar of Scariff

The Wreck of The Hercules

Famine and America

The Lady of Horse Island

The Great Snowstorm

In Quest of Happiness: A Traveller’s Tale

V Customs and Beliefs

A Family Wake

Old Medicines

Matchmaking

Penance and Grace

Copyright

PREFACE

Whether by desire, design, or accident on the part of my good parents, I squawked and squalled my way in 1906 into the Gaeltacht of Ballinskelligs on the southern shore of the beautiful Iveragh peninsula. Sleeping and crying as a child, laughing and talking as a boy, the constant music of the Gaelic tongue fell softly on my ear. The language of the Sasanach was seldom used in our family or among the neighbours.

At national school I experienced a new set of growing pains, pains of a physical as well as a mental nature. The master was a stickler for accuracy, and when English was in session he would growl and wield his hazel wand, shouting ‘Watch your grammar!’ I learned English not through curiosity or love, but in fear and trembling.

I have tried to write with honesty and from the heart, presenting to the reader a picture in story of rural life in Ballinskelligs during the first half of the twentieth century. Many of the little things which fitted into the jigsaw of our daily lives have now, alas, become only a memory. Therefore I give you Skelligside, a glimpse into the simple life once lived by our ancestors.

Michael Kirby

I

My Own Place

AN EARLY SCHOOLING

My mother, Mary Cremin, told me that no professional medical aid was available on the night I was born. A local woman, who knew the traditional skills of midwifery given to her from generations, gently directed and delivered me over the threshold of the womb into this world. I drew my first breath on 31 May 1906. I was the last of the little clutch of five boys and two girls.

At the age of five I was sent to school. I remember being neatly dressed in a skirt of blue frieze, and a frilled pinafore tied with white tape across my back. Few wore boots and trousers in my class. The master, Cornelius Shanahan, entered my name in the school roll and kindly presented me with a penny. But alas, on that same day I came to grief. While playing in the school yard I fell across a shallow pool and lost that first penny. My sister Sheila took my hand in hers and led me home with soothing words. Thus ended my first day at school.

As time went by I got used to school routine, though I was not in love with learning yet. The master’s snake-like hazel rod was eternally busy. Because of my slow rate of progress in arithmetic, the portion of my anatomy between rib-cage and buttocks was massaged by that same rod. I would rather see the devil himself than the long tot on the blackboard: I often reached the top figure helped by several applications of hazel.

Everything about my schooldays now seems to belong to the Stone Age, even the blue-black slates we used instead of copybooks, with pencils of the same material. Pupils had to stand back-to-back in twos to prevent copying, though we would sometimes whisper words or figures to each other when the teacher was not looking.

The grown boys played football in the little field attached to the school. The ball was made of long cloth strips, wound solidly and hand-sewn with every conceivable kind of twine. It had a certain amount of dull bounce, and it made do. Many boys wore long flannel skirts, often pleated like the Scottish kilt. Sometimes it was impossible to differentiate between the sexes, except when the boys held up their skirts to water the lawn.

During play-hour a team was picked of ten a side. The game waxed fast and furious, no quarter given and no quarter called for, no referee, no set rules, the pupils on the sideline urging on their favourites. After the game it was not unusual to notice some of the warriors nursing minor injuries: maybe a bloody nose, or a pendant of flesh hanging from a bare foot, where a big toe had been stubbed against a jutting ground-stone. Our teacher, a kind-hearted man who missed no opportunity to perform a good deed, would immediately apply some ointments he kept stored in a cupboard for such emergencies.

Many and varied were the games played in my young days. We played games with stones, such as casting a stone from the shoulder. The cast was made from a special mark. The weight of the stone varied – light, medium or heavy, three pounds, six pounds, or eight pounds. It was usually round, clumsy, smooth and difficult to grasp. The throw had to come straight from the shoulder, and any step over the line meant disqualification for the contender. It is said that nimbleness beats strength, so a brawny contestant was sometimes defeated by a lean and scrawny opponent, much to the delight of the onlookers. I remember rounders being played when we were schoolchildren. I do not recall the rules, except that it was not unlike cricket. Several players stood in the formation of a wide ring using a crude round bat or stick. After a strike a series of runs took place before the ball was retrieved. The ball consisted of sewn leather filled with some substance like sawdust.

Another game called ‘ducks off’ was extremely dangerous to both spectators and participants. The ducks were pieces of round hard stone three or four pounds in weight. A large flat stone was placed about fifty feet from the line where each throw was made. This stone was called the ‘Granny’. The ducks were first rolled from the line towards the flat table by a team of six boys. The boy whose duck was found to be farthest away from the ‘Granny’ was obliged to place it on the table to be shot at by the other boys. After each throw, a scramble would ensue for the boys to get back to the line if the stone remained stationary on the table: those who failed to get back to line on time would be eliminated. This game was intricate, and dangerous to participate in. One of our players suffered a blow to the head which made him temporarily unconscious. Before collapsing, he put his hand to his head and exclaimed ‘Oh boys, I am dead forever!’

The teacher warned us not to loiter on our way home after school. We were fond of delaying near an old ruined house by the roadside, where we played various harmless games such as long leap, hop step and jump, and frog’s leap. One particular contest led to our undoing. This was a competition to find the boy who could piss the highest. It meant pissing over the wall of the old ruin which had different levels and was ideally suited for the purpose.

Some busybody who had seen the boys at play told the teacher of our pranks, and he punished us and informed our parents. My mother was appalled. She exhorted me to change my evil ways and to confess my sins immediately. I lived in terrible fear of God, though to me He seemed a much nicer person than the teacher or the priest. We did not consider our competition to be so sinful or obscene. It was great fun while the water lasted. I do not know if any records were broken. One boy pissed sideways, so because of his poor aim he was barred from the contest. It was not considered safe to stand near him while competing. We called him Paddy Sideways. Later on we were bombarded with hell-fire, brimstone and eternal damnation. We were labelled as young blackguards by the breast-thumping holy-water hens who were usually whispering into the ear of the village pump. They foretold we would eventually bring ruin and shame on our respectable parents.

For me there was a second fall from grace during that school year. I was coming nine years old. My mother kept a flock of Rhode Island Red hens, and with them a beautiful strutting rooster. The creature had a curved tail like a golden rainbow with a few blue-green feathers for decoration, two bright looping gills hung like rubies from his jowl, and his slender yellow legs were adorned with formidable spurs. I think he was my mother’s ‘sacred cow’. He would perform a pirouette in front of her when she fed the hens.

One evening as I arrived home from school he was standing supreme on the doorstep of our kitchen. I tried to walk past but he attacked me by flying in my face. I aimed a kick at him and blurted out, ‘Be off, or I’ll kick your bloody arse!’ My mother nearly fainted upon hearing my new language. She took me inside and started to wig my ears. My father, who was weaving a lobster pot, intervened. ‘Don’t be harsh,’ he said, ‘he is only learning.’ Looking back now, we were a group of young mischievous scallywags who were wont to break the standards of behaviour required by the strict rules of the time.

Ballinskelligs National School was built in the year 1867. A hedge school catered for the locality until then. On the first day of July 1909, the school was allowed bilingual status. The region was densely populated before the Great War of 1914, and all the people spoke the melodious and subtle Irish of the region. English Schools’ Inspectors conducted all examinations in those years – Dale, Welpley, Lehane, Alexander and Cussen. I often saw the teacher grow pale on their arrival in the classroom – he would not expect an iota of pity from these grim-faced taskmasters.

Examinations on Religious Instruction took place once a year. The inspector was usually a Catholic priest who often conducted the examination in English. Some of the senior boys were showing poetic talent by composing light religious poetry:

‘Whomadetheworld?’

‘PaddyFitzgerald

Withaspade

andashovel.’

The infant class were not slow at learning from their elders, so the Reverend Examiner was astonished to hear from the smaller children that Paddy Fitzgerald was a powerful deity, much to the consternation of the teacher, who seemed to suffer hot flushes. I remember one question put to a pupil in my class: ‘Did God create the devil, my child?’ The answer came in faltering English: ‘He warn’t any devil when He made him, Father.’ Another question: ‘When were you born, my child?’ brought the reply: ‘The night of the Biddy, Father!’ The child meant she was born on the feast of St Brigid. Nevertheless, we had a good grasp of the catechism and all aspects of the faith, and the priest usually gave us good marks.

Neither priest nor monk, father nor mother, nor even the teacher himself told us anything about the birds and the bees. It was not right for us to mention sexual matters. I did not know exactly where I came from. Now, when my body was growing and my sexual organs were awakening, I thought something very strange was happening to me.

I understood from the faint whisperings that sex was very sinful – sinful to speak of, to think of, to look at, to touch, to read about or listen to. That very same sex was swallowing souls into hell every moment. An old man I questioned about it said ‘Blind people are a great pity.’ Everything about sex was a mysterious secret in my youthful days. Those who fell victim then to the pleasures of the flesh caused a public scandal.

I remember the first time I laid my eyes on a naked young woman. She was having a swim nearby one summer’s day. Every vein in my body burst into flame. Beauty drew me to her, a beauty kept secret from me until then. Then a sudden fear possessed me. Is this original sin, the seed of all sin? Is it Satan who creates this desire in me – a deadly mortal sin in front of me? Oh, blind people are a great pity! So the old man said.

THE RICHES OF THE SEA

When I had grown a little older and my bones were stretching, the Great War broke out. What a change it brought into being! The old adage says that Death is seen on the face of the old man and on the back of the youth. Destruction and shipwreck were visited on the south coast during that time. Sudden death lurked beneath those once peaceful waters, now a hiding-place for powerful submarines of the warring nations. Many a proud merchant ship was sent without warning to the bottom of the sea – the crew unable to take to the boats before the deafening roar of the exploding torpedo. Within minutes nothing was left but little pieces of torn wood and the corpse of a sailor being borne away on the ocean stream.

All kinds of wreckage came ashore on Ballinskelligs beaches then, including empty lifeboats and dead bodies from the Lusitania. A substantial reward was offered to the person who discovered the body of Mr Vanderbilt, the American banker and millionaire who perished in the sinking of that great ship. Police and coast-watchers scoured the beaches of Cork, Kerry and Clare in search of his remains. It was rumoured that these were found on the Clare coast in an advanced stage of decomposition.

On New Year’s Eve 1916 four hundred wooden casks of white paraffin came ashore at the little beach in the creek of Boolakeel. The entire population of the little hamlet converged on the beach and rolled the casks to a place of safety above the breakers. Some took barrels home, but to no avail. Members of the Royal Irish Constabulary came and searched every house, every field and dyke, even the manure heaps. My neighbour had a few gallons stored in a tub in the cowhouse, where they were found by the sergeant. He took the tub to the doorway and spilled its contents into the drain. I do not wonder why the people rebelled against British rule in Ireland.

Fish was plentiful during those years. My father bought a small rowing boat, specially ordered to his own dimensions, for line and lobster fishing. The first I took on board myself was a pollack about eight pounds in weight, but I imagined it was as big as a horse. My father praised me on how well I handled it. I was eight years old then. By the age of ten, with constant practice, I had mastered the art of rowing with short paddles. We filled large casks with white fish, mostly pollack and cod, cured in brine and dried, and my father sold it for three pence per pound. Many a day we would row westward under the great cliffs of Bolus to the most likely places, which my father would pinpoint by getting certain landmarks on shore into line. When he reached the desired position he would order me to cast the mooring-stone and make fast. As soon as we had our hooks baited with glistening cubes of fresh mackerel or mussel and set for bottom fishing, we were kept busy hauling until the little boat was heavy with a varied catch of codling, red sea bream, large whiting, grey and red gurnard, ling and ray. Those were halcyon days of my youth, which time will never erode from the living cells of my memory.

One day while we were westward in the bay, my father took what seemed to be a heavy fish on his line. After a long struggle, he caught sight of the great creature for a fleeting moment. He knew immediately it was a large halibut. No sooner had the fish surfaced than it plunged again to the depths of the sea, taking all of thirty-five fathoms of line singing over the gunwale in its wake. My father paid out line when necessary, and also took up the slack. At one time the fish leaped clear out of the water and fell over on its back, sending a shower of white spray heavenward. But it failed to dislodge the small whiting hook stuck firmly in its jaw muscle. This exciting struggle continued for some time, with the fish slicing the water like a broad spear. It was lovely to watch the seasoned old fisherman deftly handling the pressure on the line. Only one golden rule had to be followed: not to let the fish break you when your gear was too light for the burden. After some time my father spoke urgently to me: ‘Get the gaff and look out for him!’ I knew then that the great tussle was nearly over. The noble heart of the fish had weakened, and its pulse was a mere fluttering. My father eased it gently toward the side of the boat into my reach, and I sank the barb of the gaff deeply in its side. I helped my father take the fish on board. ‘Ó,aMhuire!’ exclaimed my father, ‘Oh, Virgin, what a beautiful fish!’ It was a little short of ninety pounds, and it took only a small whiting hook and a cube of fresh mackerel to do the job.

I often listened to the old people tell of the Great Famine and how many of Ireland’s poor fled to the coast for survival. A million people are thought to have died in Munster during the Famine period. Thousands came to the rocky beaches and sandy inlets searching for shellfish – limpets, winkles, mussels, cockles, crabs, sand eels and rockling. Edible seaweed – sea dulse, miabhán, carrageen, green sleaidí – was boiled and eaten. Ballan wrasse and gunnar wrasse were very plentiful. People were seen to fish from every vantage point, even on the rocks of the most dangerous headlands. All that was needed were some small hooks, a piece of line made from home-grown flax, some lugworms for bait and a stone for a sinker. This crude fishing tackle could mean the difference between survival and death. Large hake were plentiful in the inshore waters of the south and west coast. The trawl had not yet been invented and the large foreign steam trawlers did not arrive for many a year to come. Local fishermen also brought gannets from the Great Skellig, which they salted and used as food. I heard of how the English agent who collected the land rent saw many large fish in my grandfather’s house. He warned that the rent would be increased if the landlord became aware of how well off we were.

Because of fishing, the death rate from hunger was not so high on the coast. One old woman, called the Fishing Hag, was well known in the area during the Famine. Many tales were told about her powers of attracting fish wherever she cast a hook. She always kept a supply of salted fish strapped to her back to prevent it being stolen, as hordes of people roamed the roads of Munster in quest of food. This poor old woman did not have a name and never told anyone who she was. The Fishing Hag died in the house where I was born. The neighbours and my people made her coffin, and as night was falling it was brought across the fields and buried in the old graveyard by the sea that was once St Michael’s Abbey. It was by the light of bogdeal torches that the last sod was laid on her grave.

There was a place near the old graveyard which was called Bearna na gCorp or the Gap of the Corpses. So many people died each day during the Famine that it was impossible to bury them all, and some were left near the opening in the wall until the next day.

* * *

‘Today is Rabharta Rua na hInide, the Red Tide of Lent,’ said my father. ‘Carraig an Eascú will be exposed, so bring the long holly rod from the rafters of the cow byre.’

‘But, Dad,’ I said, ‘the holly rod has neither line nor sinker this many a long day.’

‘That makes no difference, son. On certain days, you can get fish with a rod without a line or sinker.’

I did as I was bidden. I took the seasoned holly rod from the rafters and brought it along. It was all of eight feet in length and tapered to a point. ‘I’ll bring the gaff, a sack, and my knife too,’ said Dad. ‘There’s an old saying: a fisherman without a knife, a greyhound without a tail, a ship without a rudder. Come! Let’s go. You never know where lurks a lobster.’

My young heart fluttered with wings of joy as I went to search the exposed harbour reefs with a master fisherman. Standing on the shingle beach which overlooked the strand, we could see that the Rinn Dubh, the Black Reef, was entirely exposed, the Lough of the Dulce without a drop of ocean.

The sweet edible sea dulce lay in great fallen swathes like a field of ripe corn after heavy rain, losing some of its iodine content in the bleaching of the noonday sun. Because I was barefoot, Dad told me to be careful when wading in the pools lest I tread on a sea urchin. It was my first time seeing the marine anemones with their beautiful coloured fringes. I thought it odd to see things like cows’ teats growing on rounded boulders beneath the sea. I questioned Dad about what form of life they were, so very strange did they appear to me. ‘Nothing new, my boy! nothing new,’ he replied. ‘Scientists call them MetrediumDianthus. Take to the books, boy, take to the books.’ Ah! but Dad was droll.

The colours of the different anemones fascinated me. Some were ruby, some were pink and blood-red, others a mixture of green and greyish blue, their delicate feathery fringes forever opening and closing, capturing the plankton they relied on for their existence. Dad explained that many microscopic forms of life exist on both land and sea whose time has not yet arrived to be of benefit to mankind. Years later, I read some more about lesser forms of life, but I have come to the conclusion that my greatest problem is trying to understand myself.

My father showed me a narrow gravel bed between the rocks, where the cockles are found. Burrowing beneath the loose gravel, he found smooth and tiger-tooth cockles, and very soon I was able to find them on my own. We put a quantity of the choicest ones in the bag. ‘It is not so much in quest of cockles that we’re here,’ said my father, ‘so give me the holly rod, and we’ll search for lobster. Perhaps it’s yet early, after winter, but an old “Jack” may be hibernating.’

My father started to search, thoroughly and methodically, all the flat slabs of rock in the pools. He poked the slender end of the rod underneath, and explained to me what signs to look for. ‘The lobster is a hermit by nature,’ said he, ‘and will stay under a flat rock or boulder for long periods. He has usually two doors to his dwelling, an entrance and an exit. If the rock is on sand or gravel bottom, the front door will be like a rabbit burrow.’

I noticed a rock in the middle of a pool, which had about twelve inches of water around it, and because I did not have boots, Dad gave me the rod, telling me to poke underneath in the place which he indicated. When I inserted that rod I felt as if something caught hold of its tip. ‘He’s in there,’ said Dad, ‘Deal roughly with him: push the rod quickly!’ No sooner said than done: the lobster came rushing out tail first, making a clapping noise through the shallow water. I was about to grasp it, but it reached both its claws upwards menacingly. ‘I’ll show you how to lift a lobster,’ said the master. ‘Slip your open hand under his armpits from the back, and grasp it firmly; a lobster can inflict serious wounds, especially with the scissors claw.’

My father reached into the water and lifted out a nice two-pound lobster. He then sat on a rock, placed the lobster between his knees, and deftly cut the nerves of both claws with his knife, before putting him into a bag which we had for lobsters only. We found two more at the western corner of Rinn Dubh before arriving at the reef underneath the old monastery. The large boulder called Carraig an Eascú lay naked. As we approached it my father said, ‘This rock was never without a tenant underneath,’ and how right he was! He inserted the steel gaff, and hooked a large black conger eel, which he released onto the strand nearby. I watched it squirm and writhe its way snake-like towards the water after receiving only a minor wound from the gaff.

The Eel Rock yielded only two large, red edible crabs, which my father put on a string. John Shea’s house stood near the beach, so Dad asked him for the loan of his spade to dig for green-shelled razor clams, which were to be had in abundance. He dug many hundreds of them, some as thick as thole-pins. When mixed with great oval clams, these make a mouth-watering chowder. The rock pools teemed with marine life: red rockling, speckled blennys and many shrimps could be seen sheltering under the fronds of the sea kelp; rowing crabs, velvet-backs, and green soft crabs swam about in all directions. There were purple sea urchins, whose internal segments are nice to eat. I saw several blue and yellow flat-headed dragonettes in the pools. I have found them in very deep water also. The fish is not edible and their spines can be very poisonous. The sea-mouse and the little scorpion crabs were to be found beneath the sand, when we dug for the clams. Dad showed me where to find rock oysters, the flat shell cemented solidly to the smooth rock, which is always horizontal. The interior has a green-blue, mother-of-pearl glaze, and the top shell takes on the same colour as the background on which it grows, making it difficult to detect. Rock oysters have no food value. Sea cucumbers are found within the ponds and in the dense kelp as well, some brownish-black, soft and boneless, with many hundred sucking discs. Being blind, they have a compensatory sensory intelligence, and exude a white thread-like membrane as a defence. The great spider crab, with its long crooked claws and pear-shaped body, I was introduced to for the first time at the edge of low water, although I became more familiar with its freeloading habits inside my lobster pots in later life.

Queen escallops are found within the harbour on a calm day when shadow is on the water. We used to take them out with a hoop and net mounted on a long pole, and sometimes with a pitchfork. Their flesh is delicious, the orange part having a very savoury taste. Horse whelks were in plentiful supply, but only the black winkle had a commercial value. Yellow winkles, pearl winkles, striped cone winkles and miniature ear-shells shared pools with hermit crabs, showing one great claw and antenna from within an old whelk shell – a curiosity in the vast order of marine life.

The tide had now turned. As we turned our faces homewards I heard Dad murmur to himself, ‘The lower the ebb, the sooner the harbour will fill.’ I was fortunate in my tutor, who knew his environment so well, though he was hardly aware of the precious gift he was handing down to his son.

* * *

Lobsters and crayfish were very plentiful, and wherever along the rocky coast you set a pot with good fresh bait you would not look forward in vain to a black haul. The big ones could be found in the deep dark caves which were fished but seldom.