Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

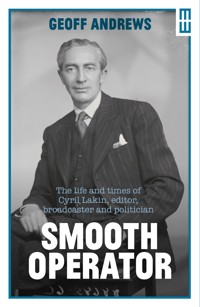

From a humble background in Barry, where his father was a butcher and local politician in the formative years of the new town, Cyril Lakin studied at Oxford, survived the First World War, and went on to become a Fleet Street editor, radio presenter and war-time member of parliament. As literary editor of both the Daily Telegraph and the Sunday Times, Lakin was at the centre of a vibrant and radical generation of writers, poets and critics, many of whom he recruited as reviewers. He gained a parliamentary seat and served in the National Government during World War II. The different worlds he inhabited, from Wales to Westminster, and across class, profession and party, were facilitated by his relaxed disposition, convivial company, and ability to cultivate influential contacts. An effective talent-spotter and catalyst for new projects, he preferred pragmatism over ideology and non-partisanship in politics: a moderate Conservative for modern times.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 436

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SMOOTH OPERATOR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Agent Molière: The Life of John Cairncross, the Fifth Man of the Cambridge Spy Circle

The Shadow Man: At the Heart of the Cambridge Spy Circle

The Slow Food Story: Politics and Pleasure

Not a Normal Country: Italy After Berlusconi

Endgames and New Times: The Final Years of British Communism 1964–1991

SMOOTH OPERATOR

The life and times of Cyril Lakin, editor, broadcaster and politician

GEOFF ANDREWS

Parthian, Cardigan SA43 1ED

www.parthianbooks.com

First published in 2021

© Geoff Andrews 2021

All Rights Reserved

Hardback ISBN 978-1-913640-18-7

eISBN 978-1-913640-85-9

Cover design by www.theundercard.co.uk

Typeset by Syncopated Pandemonium

Printed and bound by 4edge Ltd

Published with the financial support of the Welsh Books Council.

The Modern Wales series receives support from the Rhys Davies Trust

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A cataloguing record for this book is available from the British Library.

Contents

Preface

1. A Man from Somewhere

2. The Lakins: Making a Mark in Barry

3. Oxford

4. Lieutenant Lakin

5. Recuperation: New Horizons

6. The Berry Brothers

7. Vera: An English Marriage

8. Fleet Street Editor

9. Appeasement: Divided Loyalties

10. Meeting Hitler

11. BBC Broadcaster

12. The Barry By-Election

13. Politician

14. The Lost Worlds of Cyril Lakin

Endnotes

Note on Sources

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface

In 2016, while looking through George Orwell’s BBC correspondence for something else, I came across a 1943 entry for Cyril Lakin, whose surname connected me to family on my mother’s side. Orwell, who was then working in the BBC Talks department, had recommended Lakin, a politician with previous broadcasting experience, as a possible presenter for a forthcoming radio programme. At the time I had only a vague recollection that he was a distant relative (my uncle’s uncle) and that he had been an MP during the war. I began to learn more about him and embarked on the trail that took me to his daughter Bridget (then aged eighty-nine and living on the Isle of Wight), gradually assembling the disparate components of what I came to realise was an unlikely and, in many ways, extraordinary life.

Who was he? Where was he from? The very English circles in which he moved, and the culture and institutions that he thrived on and fully embraced, belied quite different origins. Born in Barry (where I spent my early years), he shared the seemingly obscure background of others from that modern port that had emerged abruptly and unannounced on the back of the South Wales coal industry. One of my first discoveries was that his father Harry, a native of Birmingham who had moved to South Wales in the early 1890s, had been one of the pioneers who helped make the new town; a butcher in Cadoxton when that district was beset by disease, poverty and crime, he served as a councillor on several of the committees that shaped Barry’s modern infrastructure.

Beyond that, there was very little to go on. An inaccurate Wikipedia item describes him as a farmer while another listing seemed to confuse him with a nephew (also called Cyril) who had been a farmer as well as a local councillor. He has no entry in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, nor has there been much written about him in secondary accounts of Welsh politics and history. I could see that the enigma was partly explained by his humble beginnings in that new Welsh urban settlement, comparable in some ways to an American frontier town. Aspirational Barry was a stepping stone for him as it was for his contemporaries and the generation that followed, among them the politicians Barnett Janner and Gwynfor Evans, composer Grace Williams, journalist Gareth Jones, the cartoonist Leslie Illingworth, the historian John Habakkuk, and United Nations diplomat Abdulrahim Abby Farah. Lakin’s journey by South Wales standards took a different route, facilitated by a doting mother, inspiring headmaster and influential High Anglican vicar who helped get him to Oxford with the prospect of a career in the Church.

As I pieced together the different fragments of his life from scattered Welsh archives, old BBC scripts, letters from the 1920s that had remained in my cousin’s attic at Highlight Farm, regular conversations with his daughter, and the editorial correspondence of the Sunday Times and the Daily Telegraph, it was evident that the life-defining connections that transported him to Fleet Street, the BBC and Westminster also had distinctive Welsh origins. The story of William and Gomer Berry (later Lords Camrose and Kemsley), the two powerful press barons from Merthyr Tydfil, has never been told in full (least of all in Wales). It was their influence (which at its peak matched that of Rothermere and Beaverbrook) that made Lakin’s rise possible and helped establish his roles in both the literary world and the appeasement debate (and an ill-judged meeting with Hitler), a wartime broadcasting career and, finally, a return to Barry as its MP.

Chapter 1

A Man from Somewhere

In common with many of the families who helped to build modern Barry, the Lakins had their origins in England. In their case it was the Midlands. Cyril Lakin’s father Henry (‘Harry’) was born in what is now the Birmingham suburb of Erdington (then classified as Warwickshire) in 1870, the son of James Lakin, a wire drawer, and Eliza Jones, born in Herefordshire to a farmer originally from Cardigan, West Wales: Farmer Jones, Cyril Lakin’s great-grandfather, was in fact his sole Welsh ancestor. James’s father Joseph was an agricultural labourer who set up home with his wife Elizabeth and their seven children in Bell Lane, then part of a hamlet where most of his neighbours worked on local farms. In the late 1860s Bell Lane was renamed after the huge orphanage built there by Josiah Mason, the self-educated industrialist and philanthropist, who also constructed almshouses nearby as a further contribution to the well-being of the poor. At the top of the orphanage was an enormous 250-foot tower, from which Sir Benjamin Stone, a notable documentary photographer and later Conservative MP, compiled his panoramic images of the surrounding area. Stone, who would become the first mayor of Sutton Coldfield, embodied the civic and entrepreneurial spirit of Victorian Birmingham that had a lasting influence on Harry Lakin.

After Joseph’s death in 1860, Elizabeth worked as a registered nurse while her children supported the family through their work as labourers and dressmakers. James found regular work in local industry and, after his marriage to Eliza, moved a couple of streets away to Easy Row, Sutton Road, a working-class thoroughfare in Erdington village where their neighbours were a mixture of skilled and semi-skilled labourers and small shopkeepers. Here Harry Lakin was born, their only son among six children. His upbringing suggests an importance given to a stable family life, with religion playing an important part in the shadow of St Barnabas Church (where he was baptized). His schooling was brief but adequate in its basic instruction to enable him to decide on a trade as a butcher. Beyond his trade he had wider ambitions, including an early interest in civic affairs inspired by the example of Joseph Chamberlain, whose tenure as Birmingham’s Liberal mayor had brought a range of municipal reforms such as slum clearance, libraries, parks and museums, and encouragement for local artisans. Nineteenth-century Birmingham was at the centre of transformations in local government, though by the time Harry Lakin had begun work Chamberlain was already an MP, representing the Liberal Unionist wing and disaffected with Gladstone and the Home Rule legislation. From Harry Lakin’s subsequent brief political career in Barry it appears that Chamberlain’s evolution from entrepreneur to civic champion had left a marked impression on him, though he did not share Chamberlain’s Nonconformity, earlier ‘gas-and-water socialism’, or support for the temperance movement. He was proud that his first apprenticeship was in the butcher’s shop patronized by the Chamberlain family, a story that he would later recount in his appeal to the Barry electorate. The Chamberlains would continue to hold significance for his family: many years later, in the turbulent years of interwar British politics, Cyril Lakin would get to know Joseph’s sons Austen and Neville, who were then on opposite sides of the appeasement debate.

Harry Lakin’s horizons were broader than Birmingham, however, while his shrewd business sense, an attribute that would bring many advantages to his family, was already evident. His decision to move to South Wales was a recognition of the transformational impact of the coal industry, and informed by both an awareness that the prosperity of the communities depended upon on the migration of new tradesmen, and an optimism for the new business opportunities presented. At the beginning of the 1890s he moved to Tredegar, South East Wales, then in the county of Monmouthshire, and one of the early centres of the Industrial Revolution. The Circle was the heart of the town, with its central core – a meeting point for businesses – leading out to adjoining streets, and it was here (at number 10) that he took up employment as an apprentice butcher for Enoch Woodward. The same building would later be a local landmark as the home of the Medical Aid Society, so inspirational for Aneurin Bevan – Tredegar’s most famous resident and the founder of the National Health Service – who served on the committee that provided health assistance to the town. When Harry Lakin moved there as a live-in servant and apprentice it had different concerns, however. The master butcher and head of the house, Enoch Woodward, was a Wesleyan Methodist, a member of Tredegar Council, a Poor Law Guardian and a strong supporter of local charities and temperance causes. He was keenly involved in the life of the town, including its literary and musical societies, and as a notable local figure and entrepreneur was likely an early mentor for Harry Lakin.

After his apprenticeship in Tredegar, Harry Lakin was ready to establish himself as a butcher. Convinced by now that the coalfields of South Wales afforded new opportunities to ambitious tradesmen, he sought to be at the heart of it. He made a very wise choice in Barry, which was already heralded as the most significant emerging industrial town in South Wales, often compared with American frontier towns where new migration settlements laid the basis for new urban communities and civic cultures. When he arrived in 1891 to live at 11 Vere Street, Cadoxton, Barry was in the process of merging its three villages – Cadoxton, Barry and Merthyr Dyfan – to form an industrial centre founded on the docks, which had been opened just two years earlier. After much parliamentary and legal wrangling, The Barry Dock and Railway Act in 1884 had finally been approved by Royal Assent on the grounds that the nearby Cardiff and Penarth docks were insufficient to meet the rising demand for coal following the construction of new pits in the Rhondda Valley. The opening of Barry Dock in 1889 was the culmination of a campaign launched by the big colliery owners, notably David Davies – or David Davies Llandinam as he was known – and John Cory, who wanted to extend the facilities for transporting and exporting their coal. Both Cory and Davies were major coal owners in the Rhondda who held other extensive business interests, and their influence extended to politics, a host of philanthropic causes, temperance and Wesleyan Methodism. They received the backing of other prominent businessmen, including Archibald Hood, another Rhondda coal owner, and J.O. Riches, the president of the Cardiff Chamber of Commerce, who had first pursued the Barry Dock scheme in 1881 (though David Davies is credited with leading the battle to get legislation through Parliament).1 Initially, they had faced local opposition from the Windsor estate, the owners of Barry Island, who were concerned about protecting their business at Penarth Dock, fearing that the island, rather than Penarth, could be the prosperous Cardiff suburb; at one point the Windsors even closed Barry Island to deter tourists. However, after Penarth was established as the retreat for the Cardiff bourgeois, and the Windsors saw increased profits in the unrelenting demand for coal, there was a volte-face and they went into business with David Davies and the other coal owners.2 Moreover, the siting of Barry Dock was enhanced by the island being situated in an area that was thought to be ideal for loading coal.

In 1881 the combined villages of Cadoxton, Barry and Merthyr Dyfan had shared a population of 478; as small agricultural communities they were isolated from each other in an area still defined by the big landowners, notably Windsor, Romilly, and Jenner. After the Barry Railway Company succeeded in achieving Royal Assent to build the docks, railway stations were opened at Cadoxton and Barry Dock in December 1888 (Barry Station was opened in February the following year) along the Cogan line, with the first coal delivered in July 1889. The opening of the docks – to great fanfare and approximately 2,000 spectators – precipitated an enormous migration into Barry from other parts of Wales, and particularly from England (including many from the West Country), with Irish and Scottish immigrants moving south. The influx of navvies to work on the docks and railways provided the strong working-class core of the town. By 1896 it had grown to a population of around 20,000, only a quarter of whom were of Welsh origin.3 As a result, the population underwent significant social and cultural transformation, with the task of building its infrastructure – including its civic and political institutions – still in its early stages when Harry Lakin arrived. Urbanization had been so rapid that the living conditions were chaotic, crime was endemic and disease common. Initially, Cadoxton was intended to be the main hub of the new town and received the majority of the first inhabitants and building work, and this may have been the reason he chose Vere Street, which together with Main Street was one of two principal centres of trade. In addition to commercial premises – butchers, drapers, chemists, confectionery and newsagents were starting up – by the mid-1890s Vere Street also accommodated two banks and the Royal, Cadoxton and Wenvoe Arms hotels as well as the Cadoxton Conservative Club.

One of the consequences of the influx of dockworkers and railway workers was that it turned previously rural Cadoxton into a working-class district. The Barry Trades Council had been founded in 1891 amid the turmoil of labour insecurity and dangerous working conditions. Inspired by the new unionism of the late 1880s (which, among others, had led to the London Dock Strike of 1889) under the leadership of J.H. Jose, a future councillor colleague of Harry Lakin, it helped organize serious campaigns for improved wages and conditions. This was strengthened by the formation of the Navvies’ Union and the proliferation of meetings and gatherings in the reading rooms, temperance halls and coffee shops of Cadoxton and Barry.4

The mixture of agitation and ambition characterized the growth of Barry in the 1890s. As a purposeful twenty-one-year-old tradesman Harry Lakin had arrived in a town that was ‘booming’ with aspiration. ‘No port in the kingdom,’ the South Wales Daily News declared in the year of his arrival, ‘exhibits a more marvellously thriving record, or views the future with more confidence than this latest protégé of fortune’.5 But it also had significant social problems in its early years that affected in one way or another all its inhabitants. In Cadoxton, unfinished roads and pathways amounted to ‘mud lakes’ and ‘quagmires’ at times of inclement weather (leading to the nicknames of ‘Mudoxton’ and ‘Slushoxton’), with open sewage causing stench, disease and sanitary problems, including an outbreak of typhus fever shortly before Harry Lakin moved in. The initial overcrowding caused by the rapid migration of dockworkers co-existed with derelict or unfinished houses and illegal drinking dens (‘shebeens’), and Cadoxton became a fertile area for speculators. Crime was a perennial problem with prostitution, petty theft and violent assaults stretching the resources of the Cadoxton police, whose limited manpower amounted to stationing one of its three police constables at each end of Vere and Main Streets to quell Saturday night revellers.6

This all contributed to a difficult settling-in period and meant an even more testing time following Harry Lakin’s marriage to Annie Palmer in 1892. They were married at Cardiff Registry Office, but they most likely met in the Midlands when he was serving his first apprenticeship. Annie had endured a tough childhood in Bewdley, Worcestershire. From a farming family, she had lost both her parents when very young after they had contracted typhoid from drinking well water, and was brought up by her elder sister Lizzie. Despite the difficulties in her early years, Annie held firm aspirations, which she took with her to Barry – ones she shared with her husband and would later invest in her eldest son. Ambitions aside, building up a butcher’s business and establishing a presence in a rapidly growing and at times hazardous environment meant long hours and constant vigilance to property and person. Not long after their marriage Harry had to appear as a witness in the ‘Cadoxton Assault and Highway Robbery’ case at Barry Dock Police Court after a woman was assaulted by a local fireman who had followed her from the nearby Wenvoe Arms Hotel. After refusing him money, the woman (in a drunken state, according to Harry Lakin’s testimony) was struck in the chest outside his butcher’s shop. After refusing the man’s demand to pick up a dropped sixpence, she was then hit again in the ribs and fainted. The charge was amended to ‘assault’ (presumably as no money was taken) and ‘the ruffian’ sentenced to a month’s imprisonment with hard labour.7

These were the conditions in Cadoxton when Cyril Henry Alfred Lakin was born on 29 December 1893. While he was not a product of the classic proletariat, his early life as the son of a young, enterprising butcher making his way in the chaotic world of Barry Dock was shaped by the class character and industrial demands of the South Wales coalfield, which was rapidly turning Barry into a major coal exporting town – a second dock was opened in 1898, with the imposing Barry Dock Offices completed by 1900. Modern Barry was founded in the years immediately prior to and following his birth and saw its biggest changes during his childhood. Some individuals continued to exercise disproportionate influence on the development of the district. These included John Cory, who as director of Cory Brothers and Co shipping and coal export business had earlier been central to the decision to build Barry Dock and subsequently became Barry’s first county councillor. As first chairman of the Barry and Cadoxton Local Board, which preceded the Barry Urban District Council, he was a prominent figure who used his status as one of the richest men in Wales to support local causes. Like many of the Liberal politicians and industrialists of that time, he was a strict Methodist and teetotaller, which clearly imbued him with a certain sense of moral and civic responsibility, though he was not a regular attender at council meetings (or a notable contributor on his rare appearances) and soon resigned his chairmanship.

Many of the founders of the new town were, like Harry Lakin, immigrants from England. Some of its members would go on to be stalwarts of the town. Its chairman in 1891, the year of Harry Lakin’s arrival, was John Claxton (J.C.) Meggitt, a timber merchant from Wolverhampton, who in 1884 was one of the first businessmen to move to Barry and had been a member of the Cadoxton Parochial Committee (until its succession by the Local Board) and a Poor Law Guardian. In the first Local Board election in 1888 he had come top of the poll and by 1891 was already a ‘dominant figure’ through his capacity to introduce new ideas and turn them into plans for action. He was ‘business-like, curt and practical’ and a man of ‘strong opinions’, but also able to compromise when necessary, if it was to the benefit of his adopted town. As a speaker he was clear and precise without the passion and oratory of some of his Welsh counterparts, but in the view of the electorate and fellow board members, any lack of imagination was made up for by his common sense and ‘sound administration’. Like many others on the board he was a ‘Progressive Liberal’ and a ‘firm congregationalist’.8 Meggitt, like the younger Harry Lakin, had also been heavily influenced by Joseph Chamberlain, while he had been impressed after hearing Prime Minister William Gladstone in Birmingham’s Bingley Hall. The two Midlanders and their families would know one another for the next half-century.

Dr Peter Joseph O’Donnell, a native of Tipperary, was another of modern Barry’s founders lured by its appeal as a land of promise, enterprise and industry. In 1886 he may have had some doubts as he first entered the town after a precarious five-hour journey from Cardiff in an old furniture cart, years before the building of the railways and properly constructed roads. At that time Barry only had Dr George Neale, its long-serving medical officer, to cater for the health requirements of its growing population, and Dr O’Donnell, as he settled into his new Cadoxton home (a former ‘navvy club’) with his young wife, quickly established himself not only as a doctor but as a forthright and outspoken figure, whose honesty and sense of purpose won him respect. The ‘Hibernian doctor’ was less inclined than Meggitt to compromise (particularly, as a Catholic, on questions of religious education), but was respected for his conscientious manner and loyalty to the town.9

The political consensus on the Barry and Cadoxton Local Board came to favour the Liberal and Progressive cause, but also influential in the early years was the Cymru Fydd (‘Young Wales’) movement, whose first branch in Wales was founded in Cadoxton, mainly due to the energies of W. Llewellyn Williams, who was then editor of the South Wales Star, the local newspaper. Founded by Tom Ellis, a Liberal Party associate of David Lloyd George, Cymru Fydd had held its first meeting in London in 1886 (attended by Welsh residents of the capital) and was partly inspired by similar gatherings of Irish nationalists. In 1892 in Cadoxton, the ‘Young Wales Society’ agreed to hold weekly classes and discussions in English and Welsh on alternate Tuesday evenings, normally in the Philadelphia Welsh Baptist chapel or the vestry of the Court Road Methodist chapel. Their founding proposals were radical and included similar objectives to those proposed by the wider movement that was then influencing Welsh Liberalism, namely disestablishment of the Church of Wales, Home Rule for Wales, reform of the land system, appointment of Welsh-speaking government officials for Wales, the use of the Welsh language in elementary schools, and a national system of education for Wales.10 Williams, as president of the society, clearly believed in the early 1890s that Barry would follow the radical directions of Welsh Liberalism under Lloyd George. The pages of his newspaper were filled with sympathetic columns and letters, and he urged Barry’s Young Wales Society to ‘organise Welsh opinion in the district’.11 That he and others had underestimated the cosmopolitan nature and aspirations of the new town would only become clear later.

Politics was some way from Harry Lakin’s mind as he and Annie struggled to build the business in Vere Street, in competition with five other butchers’ shops, including the Colonial Meat Company next door. In their first years in the shop they were always ‘exhausted’ and after a long day at work just ‘flopped’, with little time for anything else.12 It did not help that Harry and two other Cadoxton butchers were among the first to fall foul of the Barry and Urban District Council Act, which outlawed the exposure and sale of blown meat (an old practice that ‘plumped up’ the meat to give it a healthier appearance). In his defence he argued that as he had killed his own animals, he could not understand why it was wrong to have the meat blown, but along with the others was fined a nominal charge of ten shillings.13

Despite the difficulties, their efforts were rewarding and necessary as they raised a family. Cadoxton School was just a ten-minute walk away, situated on the edge of Cadoxton Common, and Cyril Lakin was first entered there in April 1898 to attend its nursery classes at the age of four years and three months.14 His admission to the school coincided almost exactly with the desperate coal strike of that year, which would last six months and leave families suffering, including all those in Barry who depended on the mines for work. By this time Barry had established some strong labour representation, with its Trades Council now prominently active in local affairs. The arrival in 1895 of John Spargo, a Cornish stonemason, further increased the political agitation in the town. Spargo, later one of the first biographers of Karl Marx and a prominent public intellectual in the US, set up the Barry branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), and this, together with his leading role in the Trades Council and his position as a prominent opponent of the Boer War, for a while made him an influential figure in Barry. The strength of the SDF in the navvies’ lockout of 1896–7 illustrated the potential power of union organization and the dissemination of socialist ideas, which extended beyond improved wage rates to the provision of medical, social and cultural resources.15

This meant that there was strong support for the strikers. In addition to the dockworkers affected, around a hundred sailors were stranded for a time at Barry Dock. Free teas were given out to hundreds of poor children in the town and Harry Lakin, mindful of the town’s dependency on the industry, regularly contributed free meat to the soup kitchens that sustained the community over the five-month duration of the strike. At the beginning of July, the Barry Dock News reported that ‘destitution in the town is becoming more and more pronounced’ and further appeals had to be made for charitable contributions, with Cadoxton School helping to distribute the proceeds to families.

Cadoxton School had opened in 1879 (with a new building added in 1887), and was housed in a typically imposing Victorian building at the top of a hill, situated in what was still an agricultural village at the time it was built. In 1898 the building was still incomplete, with school walls in need of paint, ‘badly constructed’ galleries, and with backrests missing from some of the seats, but Miss Carr, the headmistress of the infant school, was praised for her ‘intelligent grasp of the work of the school’ and for the supervision of her staff: a combination of certified teachers, trained assistants and pupil teachers. When Cyril Lakin was admitted there were in excess of 400 pupils in all, though attendance and punctuality was a matter of concern. It would have been a relief for his parents to leave him in capable hands for much of the working day, while Annie took his education very seriously even from an early age. They were attentive parents, and if in his early years their working hours meant they sometimes had to miss out on pantomimes and shows, Harry Lakin would read him stories before bed, with Aladdin, the classic rags-to-riches tale, a particular favourite in his son’s memory.16

Despite the obvious restrictions and limited resources of Victorian education as he moved through the school, he and his Cadoxton classmates were encouraged to make the most of their environment and pursue nature studies on Cadoxton Common and the surrounding area, with occasional visits to Barry Island. They were introduced to clay modelling, bead shredding and drawing, in which Thomas Ewbank, the headmaster of the main school, took a keen interest.17 Ewbank was a central presence in Cyril Lakin’s early life as an active and benevolent participant in Cadoxton activities. He was on the ward committee of the local Conservatives and a district master of the Cardiff Oddfellows, as well as a prominent promoter of many other cultural and educational initiatives in Cadoxton, presiding at lectures on astronomy and hosting musical evenings at Barry’s Theatre Royal. He was a founder member and treasurer of the Allotment Holders and Cottage Gardeners, which was instituted to encourage the ‘mutual improvement of the working man’.18 As a long-standing member of the local school board (local education authority after 1902), he was at the centre of some important decisions over school finances and staffing and sometimes embroiled in battles with religious figures such as the Baptist minister Ben Evans, the Reverend Pandy John and Dr O’Donnell. He was often asked to explain the high levels of truancy and variable attendance as well as acts of vandalism when some of his boys had been stoning trains or smashing windows. At the same time, he was proud to present to the committee examples of outstanding attendance and other school achievements. His commitment and loyalty to the school was evident to his pupils, even if at times he appeared as a strict custodian of rules and procedures. With limited resources he did his best to instil in his charges some sense of responsibility and to introduce new experiences for them, whether by establishing the Cadoxton School Fife and Drum Band or instructing them in singlestick drills. At the time of the coronation of King Edward VII, he was chief marshall at the celebration at Buttrills fields that was attended by 7,000 local schoolchildren. When Cadoxton was facing particularly difficult times of distress during the coal strike and in the early years of the new century, he supervised on the school premises the provision of food and beverages for those in most need.

The efforts of Mr Ewbank and the other teachers offered some security for Cyril Lakin as he made his way up to the school from Vere Street, through Main Street, or the slightly longer but more pleasant journey up Little Moors Hill. Here he could cast an eye at the relatively salubrious Belle Vue Terrace, a set of villas inhabited by Dr Edward Treharne, a prominent surgeon, former rugby union player (who had played in Wales’s first ever international against England in 1881) and leading Conservative; and Miss Small’s Belle Vue School for Girls, which catered for the children of Cadoxton’s more affluent residents.

Cyril Lakin’s early schooling was important, but his parents, regular churchgoers, also sent him to attend the Sunday school run by St Cadoc, Cadoxton’s ancient village church. Renowned for its architectural distinction and sheltered by yew trees, it had undergone significant restoration in the 1880s. At the time of their arrival in Barry, the rector was Ebenezer Morris, well known in Cadoxton as ‘Parson Morris’, who cut a distinctive figure around the district in his wide-brimmed black hat.19 A Cambridge graduate who married the daughter of the local ‘gentleman’ of nearby Buttrills, Morris was the father of nine children. Regarded as ‘conscientious’ and a ‘genuine friend of the poor’,20 he enjoyed the respect of his parishioners as ‘one of those Anglican clergyman whom [Thomas Babington] Macaulay must have had in mind when he declared that the Establishment was worth preserving even if only for the guarantee of the presence of one gentleman in every parish of the land’.21 Parson Morris was wise enough, however, to adapt to the needs of the new population as Cadoxton underwent transformation from a rural village to a working-class port suburb. Though St Cadoc experienced the same chaotic upheaval as other religious bodies and was barely able to accommodate the new arrivals in a church building in need of updating, his sermons would have offered some spiritual reassurance to the Lakins as they started out.

It was Morris’s successor, the Reverend John Smith Longdon, who was the main influence on Cyril Lakin’s early life. Longdon, who took up his position in December 1902, was a Welsh-speaking Oxford graduate from Clydach in the Swansea Valley who had earlier practised at Aberdare and Hirwaun. A talented sportsman who had played rugby for Oxford University, Swansea and London Welsh, he and his wife Zoe (‘a model Rector’s wife’22) brought more energy into the activities of the parish. Longdon had played a pivotal role in building the Sunday school movement among Anglicans, and in Barry his classes were often packed and in need of additional accommodation. Aware of Longdon’s background, status and influence, Annie Lakin was determined to put her son in his charge. Cyril Lakin was not only one of his young parishioners, he also delivered meat to the rectory on his bike as part of his weekly delivery run. He was a willing participant in the sports programmes, sang in the choir and was ever-present at bible-reading classes. More than that, he saw Longdon as an early mentor, whose encouragement in his education and sporting activities was crucial to his formative development. Longdon nourished Lakin with an early ambition to follow him into the Church. His interest and commitment evidently impressed, as did his amiable disposition, which many of his elders took as indicative of his personal charm. Like her husband, Zoe Longdon saw the potential of their young protégé and kept a keen eye on the progress of this ‘dashing/beautiful young subaltern’.23

The Reverend Longdon was the last lay parson in the parish before disestablishment and disendowment of the Church in Wales, and he had to compete with the strong Nonconformist denominations that had spiralled in the new town. As a preacher he was admired for clarity and lucidity of expression rather than emotional rhetoric, though his adherence to unfamiliar rituals and ceremonial practices got him into some serious difficulties with some of his own parishioners, who found his endorsement of the Oxford High Church movement unpalatable and some divergence from what they had been accustomed to under Parson Morris.24 However, the Lakins stood by him and their involvement with the church endured, and Harry and Annie remained regular attenders at church events and functions.

By this time Harry had acquired bigger premises for his Vere Street business, directly opposite at number 53. His neighbour was newsagent Thomas Fairbairn, widely thought to be the district’s oldest resident having moved from Scotland thirty years before. As the new district emerged from the early social upheavals, a growing community helped provide mutual support. When his finances were low, Fairbairn’s son, J. Clark Fairbairn, a talented artist, would offer his paintings to Harry Lakin in lieu of cash payment for meat.25 The Lakins themselves in their early years in Cadoxton struggled to make ends meet and had a larger family to support following the arrival of brothers Stanley (1900) and Harold (1903). However, it was the firstborn who continued to receive most attention. Annie ‘doted on him and saw and nurtured his talents’,26 and Cyril formed a strong emotional attachment to his mother that extended well into his adult life. Her encouragement of him was driven by her desire to get him out of Cadoxton and move on to better things. Beyond his school and church commitments, she arranged regular singing lessons with Professor W.H. Shinn. Shinn, who would later have a distinguished career in Canada (lending his name to a conservatory of music), taught voice and piano and was an enthusiastic promoter of Barry’s musical talents, registering students for nationally recognized music awards – Cyril Lakin was among the 1903 cohort who passed London College of Music examinations – conducting local choirs and championing Barry’s case to be given the national eisteddfod. He felt it was better suited than other ‘less important and less attractive’ places that had recently hosted it and would be a ‘first-rate advertisement for the town’, as well as bringing educational and cultural benefits.27 In fact Barry would not host a national eisteddfod until 1920, by which time Shinn had emigrated to Canada. He was a well-respected figure in Barry and aspirational parents sought his services.

It was probably in this group that he first met Barnett (‘Barney’) Janner, who with his older sister Rachel (‘Ray’) also showed early musical promise under Shinn’s tutelage. The Janner family had moved to Barry from Lithuania via the United States in 1893 (when Barney was nine months old), with his father Joseph Janner opening a house furnishing store in Holton Road, the main thoroughfare in Barry Dock. The Janners were one of the first Jewish families to arrive in modern Barry, and his father gave Barney daily lessons in Hebrew. As with the Lakins, life was hard in the early years, and made worse after the Janner family was struck by tragedy in 1902 when Barney’s mother, very religious and learned like her husband, and conversant in several languages, died giving birth to twins, who also died shortly after. His father’s business acumen did not match that of Harry Lakin (he had trouble retrieving unpaid debts from sailors), and Joseph was forced to start another temporary business.28 After the Janners settled, they helped establish a very small orthodox Ashkenazi Jewish community in Barry – Cardiff by contrast had a Jewish population of approximately 1,500 and two synagogues at the turn of the century – but once the first Yamim Noraim (High Holy Days) had been held in 1904, they were at the forefront of organizing activities, with Barney involved from a young age.

The Janners and the Lakins shared the difficulties and deprivations of Barry at this time, but also saw the opportunities of making a life and improving the prospects of their children. This they shared with many others in the increasingly cosmopolitan town, which had drawn in young families from across Britain and been diversified further by the comings and goings of workers from all parts of the world, some of whom continued to live in desperate circumstances in accommodation arranged by seamen’s missions, such as The Priory in Barry Dock. In running small businesses their story was a different one from the working-class dockworkers and labourers, but there were common experiences too. By 1901 Barry was exporting more coal than Cardiff, with significant effect on the economy of the town. At the beginning of the new century the Lakins were making their mark in Barry, and other family members, encouraged by Harry’s endeavours, followed him to the town. Three of Harry’s five sisters moved from Birmingham to Barry and they were later joined by his father and mother, as well as a Bewdley nephew of Annie. Julia, the eldest of the sisters, was the first to arrive after Harry, marrying Edwin Williams, a butcher from Aberdare who ran a business in Pyke Street. Shortly after, two younger sisters, Edith and Ethel, both of whom had worked as dressmakers, married grocers in Holton Road. Edith’s husband, Frank Bee Wilkins, a native of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire, quickly absorbed the entrepreneurial ethos of the district, which he was keen to convey to his customers:

Mr Frank B Wilkins of the Central Stores 147 Holton Road, Barry Docks, is one of the most enterprising and go-ahead young tradesmen in the town. The latest addition to his already up-to-date establishment is a Raisin Seeder which stones the fruit absolutely clean. In order that the public may test the quality of his fruit, he undertakes to stone all raisins FREE OF CHARGE. Under his own personal supervision, by stocking and selling only the best quality, Mr Wilkins has worked up one of the best businesses in the town, which he conducts on the very latest and most modern principles.29

Harry Lakin, like his brother-in-law, was looking to get ahead, and by the early 1900s he had established himself as a master butcher and a leading participant in the activities of the Barry and District Butchers and Cattle Dealers Association. Each year, along with fifty or so other butchers, he attended its annual dinner at superior venues like the Barry Hotel or the Royal Hotel in Cadoxton, dressed in a dinner jacket adorned with the national emblem (leek) to enjoy a feast and musical accompaniment, and to toast ‘kindred associations’. The butchers would share their worries over infected animals, complain about the cattle inspectors, lament the Urban District Council’s continual disregard for their concerns and look forward to another year of increased trade. He was a steward on its annual competitive walk to Aberthaw and exhibited his horse and cart at the Barry May Show and Horse Parade. In future years he would become the association’s president and help promote their cause on the council.

However, it was becoming initiated as a Freemason that was of greater value to his standing among fellow tradesmen and the route to prominence taken by many leading figures in Barry. Freemasonry, a movement of ideals and influential patronage, both secretive and ubiquitous, was central to the making of modern societies. That ‘fellowship of men, and men alone . . . bound by oaths to a method of self-betterment . . .’30 was instrumental in disseminating the new values that would sustain public life in emerging towns like Barry. Barry Freemasons Lodge had been consecrated in 1890 at Dunraven Hall, opposite Cadoxton Station, soon after the opening of the docks. The founder members of the lodge reflected their status within the new town. Its first Worshipful Masters were J. Jewel Williams, landlord of the Royal Hotel in Cadoxton, and Dr Neale, the town’s medical officer, while Dr Treharne took on the same role in 1895. Other early members included John Alexander Davies, proprietor of the Barry Hotel, Parson Morris, and several tradesmen and schoolteachers, including Thomas Ewbank. In 1900 it moved its meetings from the Royal Hotel to the palatial rooms of the Barry Hotel, centrally situated on Broad Street. Six years later, they would open their own Masonic Hall in new premises alongside the hotel.31 Freemasonry was taken seriously in Barry as a measure of local esteem as well as an obvious vehicle for benefits and privileges, and Harry Lakin would have judged it worthwhile to invest in the ten guineas required for initiation into its ranks. In doing so he agreed that ‘whatever his trade . . . in all his social and business transactions [to] deal honestly and squarely with his neighbour’.32

When Dr Treharne died unexpectedly from a heart attack in 1904 at the age of forty-two, a mile-long cortège in Cadoxton slowly made its way down Vere Street, enabling his patients and fellow dignitaries to pay their last respects. After the funeral (‘confined to gentlemen’), Harry Lakin joined others at the graveside, where

for fully half-an-hour the large assemblage filed round the open grave to obtain a last glance at the coffin of one who was respected and beloved by all, rich and poor alike, and as one by one the freemasons passed the same affectionate tribute over the grave of their departed brother, each dropped on the lid of the coffin a sprig of acacia, as the particular token of love and of sorrow prescribed by the craft for use on such occasions.33

Treharne’s death left a gap in the Conservative presence in Cadoxton, which a few months before had, along with the rest of Barry, returned a Progressive majority to the Urban District Council. Cymru Fydd and the Welsh nationalist Home Rulers had waned in influence since the 1890s and Llewellyn Williams, its strongest advocate in Barry, had by now moved on to seek a parliamentary seat. Despite this earlier reversal, David Lloyd George was entering the formative influence of his political career, leading a ‘Welsh revolt’ against the Conservative government’s Education Act of 1902, which in shifting power from school boards to local education authorities had privileged the funding of Church of England (and Roman Catholic) ‘voluntary’ schools. In galvanizing opposition, he reignited the radical Nonconformist tradition and revived the case for disestablishment and disendowment (though it was nearly twenty years before that became law). The Act was generally unpopular, and on the back of this strength of feeling the Progressives in Barry prepared an electoral committee for the 1904 local elections, which included representatives of the Radical Institute, Liberal Association, Labour and Progressive Association, the Protestant Five Hundred and the Free Church Council. Their candidates ranged from J.C. Meggitt, Nonconformist ministers Pandy John and Ben Evans, to Fred Walls, a former member of the Marxist SDF. Although John Spargo had moved to the USA in 1901, the pressure from Labour campaigners had continued with the formation of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900, which would become the Labour Party in 1906.

It was into this cauldron of Nonconformist radicalism that Harry Lakin – a supporter of the Education Act – ventured two years later to make his appeal as a Conservative to the Cadoxton ratepayers. He had put a lot of time into establishing his presence in the district, was well respected among his neighbours and been accepted into some of the circles helpful to advancement. His family was proud, too, that their eldest son Cyril had made excellent progress at Cadoxton School, aided in these endeavours by the Reverend and Zoe Longdon and Mr Ewbank. He had won a place at Barry County School and received the news in September 1905 that he had come fifth in the scholarship examinations, with the highest score among the Cadoxton boys. (Cadoxton girls, in a ‘remarkable’ set of results, did even better, sending ten pupils on a scholarship to the county school, at this time still co-educational.34) His parents had always understood that their son had some academic ability, but it still needed a sacrifice on their behalf to enable him to continue his schooling, and the scholarship was a crucial supplement in that regard.

Barry County School had been set up in 1896 after a sustained campaign by local councillors, who had to convince the Glamorgan County Council that Barry deserved its own secondary school rather than having to send its pupils to Penarth. Three years after its foundation it came under the influential headship of Edgar Jones, who, after being shocked by the state of the buildings and the absence of a main hall, instigated large-scale refurbishment of the site with the help of Dr O’Donnell (now on the county council). While the school took up temporary accommodation in hotels in the town, a new lecture room was built along with chemistry and physics laboratories, and a new block to accommodate the gymnasium, dining rooms and the caretaker’s lodgings. These were all completed by the time Cyril Lakin was admitted, and as he emerged from the playground of Cadoxton School for the last time and looked down beyond the familiar streets of his childhood to the docks and the Bristol Channel, he had good reason to imagine that better prospects were on the horizon.

Chapter 2

The Lakins: Making a Mark in Barry

Harry Lakin’s decision to stand for the council in 1906 seems to have owed less to the burning ambitions of a politician and more to the conviction that his status in the community would be enhanced by his election. His candidature was promoted on the back of his sound business sense, as someone who would serve the ratepayers faithfully without being directed by a political caucus. He may have taken on board the advice of one of his predecessors as Cadoxton representative, B.G. Davies, who had earlier offered to would-be candidates his summary of the ideal councillor. Warning them that they should not ‘humiliate’ themselves by canvassing door to door and ‘begging for votes’, he suggested that the best councillors were those unconstrained by the close trappings of political associations. Though Harry Lakin, at thirty-six, was younger than Davies’s recommended minimum age of forty, he shared some of the latter’s core councillor criteria. For example, as someone already established in business he had ‘proved he can manage his own affairs successfully . . . [and] could with some degree of confidence ask his fellow townsmen and ratepayers to repose some trust and confidence in him arranging their affairs’.1 Davies’s further recommendations that councillors should have acquired an aptitude for public speaking, be aware of the ‘rules of debate’, could exercise the ‘art of logic’ and be able to talk eloquently on a subject for half an hour, might have stretched Harry’s experience on the butchers’ committees and at church gatherings, though they were skills that his son would later pick up and perfect.2

However, Harry Lakin’s election had wider political overtones locally. It came shortly after the election of nearly 400 Liberal MPs (together with the first group of Labour Party MPs), which established the reforming 1906 government at the beginning of the high point of Edwardian Liberalism in Britain, with David Lloyd George’s Nonconformist radicalism the main driving force of change. In Barry, where ‘Lib-Labism’ incorporated Welsh Nonconformity, aspects of Victorian radicalism and the new labour interests – a vibrant branch of the Independent Labour Party had been formed in 19053 – under the umbrella of ‘progressivism’, William Brace, vice president of the South Wales Miners’ Federation (SWMF) and a prominent figure in the 1898 strike, was elected for the South Glamorgan parliamentary constituency. His claim to represent the ‘Progressive forces’4 bolstered his support in Barry, where Progressives already controlled the Urban District Council and were defending their seat in Cadoxton. As in 1904, they advertised strong endorsements of support from their numerous affiliated groups. The incumbent councillor, Thomas Walters, a Cadoxton grocer, sensed his position was under threat from Lakin and inserted several notices in the local press before polling day urging voters to consider his record and reminding them that he was standing at the ‘unanimous invitation of the Progressive Electoral Committee’. Education featured strongly in the election campaign, with the question of Church disestablishment high on the priorities, and this, combined with the realization that the Progressives were an organized grouping with a majority on the council, meant ‘an unusual amount of partisan feeling was aroused’.5 Pandy John, the Baptist minister from Holton Road whose candidature for re-election on the Progressive list was questioned by some who felt his increased council commitments had diminished his church duties, had been particularly vociferous on the question of religious education. He had gained a reputation for intervening on a range of social and moral issues – including trying to prevent boys from playing football on Sundays – and had begun to irritate some of his electorate. His claims that Barry was being turned into a Roman Catholic district and that High Church ministers were part of a secret society extended beyond the election and embroiled him in a public dispute with the Reverend Longdon, which was only resolved by the intervention of the Bishop of Llandaff and Pandy John’s public apology.6

Harry Lakin, in the weeks up to the election, cut a fine, confident figure around Cadoxton, immaculately turned out in suit and collar, with his impressive moustachioed features prominently displayed on the badges worn by family and supporters. His campaign seems to have been mainly confined to informal gatherings among the public and fellow tradesmen. His candidate press statement merely noted the success of his business while reminding voters that as ‘a large rate-payer’ himself, he would have their interests at heart.7 In the event, Cadoxton went against the tide of progressivism and his moderate entrepreneurial message prevailed: Harry Lakin defeated Walters by ninety votes. The other notable defeat for the Progressive candidate was in the Castleland Ward where Mr J. Marshall, another butcher (originally from Stratford-upon-Avon) comfortably defeated Pandy John. The other five seats were retained by the Progressives but the high interest in the contest brought a big crowd to Holton Road School for the announcement of the results, with the candidates paraded before the public to a mixture of cheers and jeers.8