Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

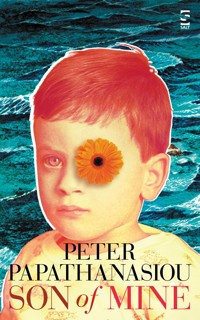

Son of Mine is a beautiful, multi-layered account of what it means to be a family. Peter Papathanasiou successfully intertwines two life journeys – his own and his mother's – over the course of nearly a hundred years, to tell the story of an astonishing act of kindness, and an incredible secret kept hidden for two decades. This exceptional memoir sensitively documents the migrant experience, both from the unfamiliar perspective of first-generation migrants and the tension felt by the second-generation trapped between two cultures. At its core, Son of Mine is about the search for identity – for what it means to be who you are when everything is torn down and questioned, and the wisdom we can pass on to the next generation. Son of Mine is a compelling account of unknown heritage, of life gifts and losses, and the reclamations of parenting. It is dramatic, poignant and uplifting. But above all, it is a memoir of shock, discovery and reconciliation, all delivered in exquisite prose.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SON OF MINE

by

PETER PAPATHANASIOU

SYNOPSIS

Son of Mine is a beautiful, multi-layered account of what it means to be a family. Peter Papathanasiou successfully intertwines two life journeys – his own and his mother’s – over the course of nearly a hundred years, to tell the story of an astonishing act of kindness, and an incredible secret kept hidden for two decades.

This exceptional memoir sensitively documents the migrant experience, both from the unfamiliar perspective of first-generation migrants and the tension felt by the second-generation trapped between two cultures. At its core, Son of Mine is about the search for identity – for what it means to be who you are when everything is torn down and questioned, and the wisdom we can pass on to the next generation.

Son of Mine is a compelling account of unknown heritage, of life gifts and losses, and the reclamations of parenting. It is dramatic, poignant and uplifting. But above all, it is a memoir of shock, discovery and reconciliation, all delivered in exquisite prose.

PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK

‘Son of Mine is an engrossing account of two lives and how choices made years previously can ricochet down through the generations. This captivating memoir considers what it means to be a parent in the widest sense.’ —CLAIRE FULLER

‘A beautifully written and incredibly moving book. The humanity, love, loss, and the compelling search for identity shine out from the pages. I loved it.’ —KATE HAMER

‘Son of Mine is absorbing and flawlessly written, telling an ultimately uplifting story about heredity, family and home.’ —ALISON MOORE

‘Reveal a secret too soon and its meaning is lost on the listener; reveal it too late and all that has been carefully built upon it can fall in an instant. In Son of Mine, a richly moving and elegant memoir that tracks between the open spaces of Australia and a small town enclosed by mountains in northern Greece, Pete Papathanasiou writes with powerful verve of the explosive secret concealed at the centre of his life until he’s already in his mid-twenties. Its sudden and unsettling disclosure forces him to reconsider everything he thought he knew about himself, his history and his heritage. What follows is a beautiful and cathartic story of love and loss, deftly charting the upheavals of the migrant experience and the raw struggles and redemptive emotional depths of a family scattered between two continents. The real revelation of his writing isn’t the unveiling of the secret, though, but rather his ability to journey with unflinching honesty through a world that is both seemingly the same and yet utterly changed for him. In this poignant and illuminating search for understanding, he discovers the deepest and most resolute of ties that bind human lives, and has created a book equal in grace to the astonishing act of kindness he uncovers at the very heart of his family.’ —JULIAN HOFFMAN

‘With the patient perfectionism of the geneticist, Peter Papathanasiou reveals the tantalising story of his own life. Shifting between both nations and generations, this exquisitely told narrative is a hymn to the love and self-sacrifice of a brother for his sister, of three brothers for each other, and is a portrait of an extraordinary family.’ —KATHARINE NORBURY

SON OF MINE

PETER PAPATHANASIOU was born in a small village in northern Greece. His writing has been published internationally by numerous outlets including The New York Times, The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, Good Weekend, ABC, SBS, The Pigeonhole, Caught by the River, Structo, 3:AM Magazine, Elsewhere, Litro, Meanjin, and Overland. He has been reviewed by The Times Literary Supplement in the UK and holds a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of London.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Peter Papathanasiou, 2019

The right of Peter Papathanasiou to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2019

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-169-7 electronic

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

1999

Chapter 2

1999

Chapter 3

1999

Chapter 4

1999

Chapter 5

1930–1955

Chapter 6

1956

Chapter 7

1956–1963

Chapter 8

1964–1970

Chapter 9

2000–2001

Chapter 10

1973

Chapter 11

1973

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

2002

Chapter 14

1973

Chapter 15

2003

Chapter 16

1974

Chapter 17

1974

Chapter 18

2003

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

2003

Chapter 21

2003

Chapter 22

1938

Chapter 23

1923

Chapter 24

1974

Chapter 25

1974

Chapter 26

2003

Chapter 27

2003

Chapter 28

2003

Chapter 29

1977–1980

Chapter 30

2004–2006

Chapter 31

2006

Chapter 32

2006–2011

Chapter 33

2012–2013

Chapter 34

2013–2014

Chapter 35

2014

Chapter 36

2014

Chapter 37

2015

Chapter 38

2015

Chapter 39

2015

Chapter 40

2015

Chapter 41

2016

Chapter 42

2016

Chapter 43

2016

Chapter 44

2017

Chapter 45

2017

Chapter 46

2017

Chapter 47

2018

Chapter 48

2018

Epilogue

2019

Acknowledgements

Prologue

You were once a newborn. It’s probably hard to imagine that now, sitting comfortably in your seat, wearing your clothes and reading this sentence. But there was a time when you were naked and new, bloody and blind, crying and cold. You were conscious in that moment, but will never remember it. You emerged from your mother’s exhausted body in a moment. The cord was clamped and cut. The events that preceded it, and those that immediately followed, were beyond your control . . .

Chapter 1

1999

It was the hottest day of summer, a Saturday in January. I sat cross-legged in my study, surrounded by piles of undergraduate textbooks, flicking through them, leaving light fingerprints of sweat on the pages. Having studied science and law for six years at university, I was about to embark on a PhD in genetics, and so was packing my old textbooks away. Seeing myself on each meticulously highlighted page, I sighed lightly, remembering all the time I’d spent understanding, memorising, and ultimately regurgitating those passages in cold, cavernous exam halls. The focus was now going to be on experiments not exams, data not grades, discovery not curriculum. Occasionally I stopped to read an extract, which brought back even more memories of lectures, lecturers, tutorials and classmates. It was a job well done, graduation with honours, but all behind me now.

Mum looked into my room again. She had something on her mind. She hoped I wouldn’t notice but it was impossible not to – she had poked her head in umpteen times that day. Having lived with my parents my whole life, I could tell when they were genuinely busy and when they were ‘hovering’. The phrase ‘helicopter parenting’ could very well have been coined for them, and especially for Mum. I knew she loved me, but at times it was to the point of suffocating her only child.

‘Mama,’ I said, ‘what’s up?’

Mum stopped, leaned against the door frame. She didn’t respond for some time. ‘Eh,’ she finally said, ‘nothing.’

‘You keep walking past my door. A dozen times now. It’s not nothing.’

She rubbed her hands together pensively. Eventually, she asked: ‘Are you busy?’

I returned to flicking pages. ‘Matters of world importance,’ I replied.

Mum was silent. Failing to sense my sarcasm, she continued to stare at me. After a few moments, I looked back up and met her gaze. It was as if she were assessing me, sizing me up for something. As she gazed longer and deeper into my eyes than I thought anyone ever could, I felt lightheaded. There were generations in that look. Mum’s stature was small, and her hands tiny, with purple veins protruding, her fingers beginning to turn in with arthritis. But at that moment, she appeared like a giant.

Slowly, almost cautiously, I closed my book. ‘Mama . . .’ I said, ‘ela, what is it?’

Finally, she spoke: ‘Can you come to my room? I’ve something to tell you.’

My stomach tightened.

As I followed Mum down the carpeted hall, a memory cut across my brain. The last time she had insisted we talk in her room was during my first year of university. My aunt in Greece had died suddenly.

Mum closed the door behind us. Her bedroom smelled of fresh linen. I didn’t exactly know where Dad was – probably out the back in his shed or at the betting shop – but knew he wasn’t in the house. The large, north-facing window amplified the hot summer sun like a magnifying glass.

‘Please, Panagiotis, sit down.’

Mum always called me by my Greek name during moments of significance. It had been there in hospital during emergencies, in church during baptisms and funerals, and at home during lectures for teenage misbehaviour. I didn’t mind it, but I knew what it meant. Someone had died, or was dying.

‘I’ll stand, Mum. Please, what is it?’

Mum took up position on the edge of the bed, her bare feet resting on a thick blue rug. Looking down at her hands, she began.

‘When I was young, I tried many times to get pregnant. Although your dad and I succeeded three times, I miscarried each time. Three.’ She held up three bony fingers. ‘One, two, three babies I carried but never met. Even after all this time, those memories are with me, every day of every week.’

I listened, silently.

‘Your baba and I wanted so much to have a family, we were losing our minds. Those weren’t easy days. We’d been through a lot, coming all the way out to Australia after the war. In the end, the time came when we thought we had no other choice. We had to consider the option of taking someone else’s child.’

Mum’s eyes suddenly welled up and her face went red. She took a deep breath. Uncertain of what was to come, I did the same.

‘Now there were places in Greece where you could adopt babies who weren’t wanted. But you needed to meet certain standards, have money and status. And your dad and I didn’t. So in the end, my brother Savvas and his wife Anna proposed to have a baby for us. They already had two sons who were almost teenagers, so their child-rearing days were well and truly behind them. But they were willing to help your baba and me. I felt terrible about my brother’s wife having to carry and give birth to another baby for me, her non-blood relative. But our lives here were childless and, well, meaningless. In the end, an arrangement was made. Anna fell pregnant, and I flew to Greece.’

A tear rolled down Mum’s left cheek. She pulled a folded tissue from her pocket and wiped her eyes. She fought hard to compose herself and not lose her place in the story.

‘Your dad worked here while I was in Greece, and sent money when he could. During that time, I completed all the paperwork that was needed to bring you back to Australia. Six months later, we flew back. From that day, you haven’t set foot in your country of birth, and the only contact with your birth mother was when she and I talked on the phone. To you, she was simply your aunt. And to her, too, this was the case. Even though she loved you dearly, it was for us to raise you in the way we chose. You became our child. She saw the benefits of life here, and it was why your dad and I came out in the first place. Your brothers, the two boys whom I’ve always said were your cousins, know everything you’ve been doing all these years.’

Brothers . . .

I put my fingertips to my temples, as if to steady myself, and let the new word nestle inside my brain. Brothers were such an unfamiliar concept. They had always been something the other kids in school had as I was growing up, in higher grades who protected them, or in lower grades whom they beat up.

‘Your brothers were, I think, twelve and ten when you were born, so should now be thirty-seven and thirty-five. Both are unmarried. The eldest, Vasilios, was named after your grandfather but likes being called “Billy” to distinguish himself. He doesn’t work and is somewhat handicapped, or “slow”, as we like to say. The younger brother, Georgios, works for a power station. Unfortunately, Anna died six years ago. Your birth father, my brother Savvas, is old and weak and plagued by alcoholism. He blames it on having to look after Billy all these years.’

Mum wiped her face and eyes again, and took another deep breath.

‘You’re probably wondering why we took so long to tell you. I wanted to tell you long ago, and keeping this from you for twenty-five years has made me grey before my time. But your dad and I knew we couldn’t tell you too young – you wouldn’t have understood. And back then, I was still too ashamed that I hadn’t had my own children. It seems so foolish now but it was cultural. The older you got and the further you went with your schooling, the harder it became to tell you. We didn’t want to do anything to ruin all your hard work. I wanted to tell you before you started university six years ago but the timing wasn’t right. The timing was never right. So we waited until you finished and were able to start work. But now, you’re about to do even more study. Your dad wanted to wait longer, perhaps another year, but I imagined by then you’d be buried in something else. At least now, the news will have some time to sink in.’

She rubbed the soles of her feet back and forth on the rug. Her heels were dry and cracked from age and exposed footwear.

‘You deserve to know this. Some parents don’t tell their kids. They keep the secret forever. But I know that even if people don’t see all that goes on, God does. There are no secrets from Him.’

Mum momentarily glimpsed skywards and crossed herself, before returning her eyes to me.

‘So,’ she said, ‘that’s it.’

While Mum spoke, I had leant against the wall, before slumping down, and finally ending up on the floor with legs bent. My skin rushed with heat. I frowned, looked away, stared out the window. I saw the empty street, the cloudless sky, and the tinderbox trees drooping in forty-degree heat. Not a single thing was moving; no birds, no branches. There wasn’t even a hint of breeze to blow around the dry leaves on the lofty gums. It hadn’t rained in months.

Mum wiped her now flushed face with another tissue. It was only then that I realised this may have been the hardest thing she’d ever done.

‘Oh wait, there’s one more thing . . .’ Mum said.

I braced myself.

‘I need to say sorry to you, agape mou,’ she continued. ‘I’m sorry for having deceived you your whole life by pretending my blood was yours. This is my confession. I hope you understand, I did none of this to hurt you. I love you. We love you – your baba and I. More than life. We’re not bad people. We just wanted to be parents. It was our dream.’

There was a long moment of silence when no one said anything. Mum and I just sat listening to each other’s breathing. And then, Mum uttered her final sentence.

‘So,’ she said, ‘now that’s it.’

Mum looked at me with the same honest brown eyes I had seen my whole life, and waited patiently for my reaction.

❦

Georgios woke at eight. Despite the bright sunshine outside his window, the solid wooden shutters kept his room in complete darkness. The house was still. He rubbed his eyes, put on jeans and yesterday’s shirt, and checked his brother’s room. It was empty. He found his jacket and snow boots, crossed the laces, tied them tight. Opening the front door, he felt a blast of cold air, and closed it behind him with a gentle thud.

Georgios’s breath appeared before him in slabs. He looked to the sky, then the ground below. There had been only a little fresh snow overnight. It would be at least a month before the accumulated falls could thaw. Icicles as long and as thick as baseball bats hung from the edge of the roof.

Descending the steps, Georgios sparked his first cigarette. He trudged across the lawn, feet sinking, heavy, the snow shin deep. The roads had been sprayed with salt again and were dirty, grey slush, slippery, treacherous.

Making his way down the hill, Georgios approached the fourno. Two stray cats darted inside, then hurried out seconds later and dived into a nearby dumpster. The air was thick with the smell of fresh bread. Stavros offered Georgios a white loaf but hadn’t seen Georgios’s brother. Georgios thanked him and walked on.

He walked past the neoclassical houses near the Sakoulevas River, listening to the sounds of morning. He heard the gentle babble of pure mountain water over stones, the honks of grand white geese, and quacks from plump grey ducks. Love padlocks sat fastened to the many small footbridges that crossed the river. It was where couples kissed and took photos. The river was at its best after rain, flowing strong and full; the town’s healthy pulse. At the height of summer, it shrank to a trickle, as lush green grasses sprouted and took the river’s place beneath weeping willows. In the depths of winter, the storm water outfalls were snapshots, each a frozen waterfall in time.

Cars slowed down and let Georgios cross the next two roads. He thanked them with a polite wave. The plateia was in sight.

Long shadows stretched across the square in the new light. The village rarely came to life before noon, and then it was only with great reluctance. Across the road, Sofia was on the balcony beating her living room rug with a large paddle. Georgios waved. The winter was the worst for accumulating dirt inside. On the corner, Georgios saw a teenage boy with his arms wrapped tightly around a girl, as if hanging on for dear life. The girl had her hands in the back pockets of her jeans and was looking up at the big white cross on the top of the mountain.

Cutting across the square, Georgios heard raised voices coming from the corner kafenion. He knew he was close. The skin on his cheeks prickled with cold.

‘Etho eisai?’ Georgios called out.

‘Yes, I am here, boss!’

Billy was propped up at the bar sipping a syrupy coffee. As he ended the life of one cigarette, he gave birth to another. In front of him, a toasted sandwich was getting cold.

‘What are you doing here? Have you been out all night? Is he giving you trouble, Dimitrios?’

But everything was fine, as it usually was.

‘Dimitrios made me a sandwich! And Yiannis was here earlier, I was telling him about when Papou won the lottery! You remember that?’

‘Of course I do, of course. Come, we need to walk home. You need some sleep and I have to go to work today.’

‘Yiannis said he would have some work for me too. I will be security!’

‘Bravo! Wonderful news, Billy.’

‘And when I have money, I will go and buy milk for the orphans.’

‘That’s very generous of you. But we better go now.’

‘Good. Let’s go.’

The two brothers walked unhurriedly, barely lifting their feet off the cracked and muddy pavement. They passed under the red illuminated sign at the pharmacy. It showed the temperature as minus eleven.

‘So Billy, what were you doing last night?’

‘Not much. Walking around. I got ink on my shirt.’

‘That’s okay. Where did you go?’

‘I went to Costas’s bar for a while. He gave me cigarettes.’

‘Give me one, will you? I’ve run out.’

‘Here.’

‘Efharisto.’

‘It’s cold,’ Billy said.

‘Very cold,’ Georgios replied. ‘Your feet wet?’

‘Yes. My toes hurt.’

‘You need new shoes. Those ones aren’t made for this weather.’

‘I went to Takis’s shop. Leonidas was there.’

‘How is he?’

‘Sick,’ Billy said. ‘His feet are still swollen. He can’t sleep.’

‘When did you last sleep?’ Georgios asked. ‘What time did you get up?’

‘I can’t remember.’

‘Let’s go home now. I’ll make you something light to eat. You can sleep.’

‘I got ink on my shirt . . .’

‘That’s fine, I’ll wash it while you rest. It will be clean when you wake up.’

‘Where is Baba?’

‘Sleeping.’

‘Where is Papou? You remember the lottery he won?’

‘Of course I do, but that was a long time ago.’

‘Where is Papou?’

‘We’ll go see him later, when I get back from work. We’ll light the candle in the lamp and see everybody together. Papou, Yiayia, Mama. Sofia gave me some flowers yesterday. They’re plastic, but they’ll last outside.’

‘And o micros?’ Billy asked. ‘When is Panagiotis coming?’

‘Soon,’ Georgios replied.

‘When do we get to see Panagiotis?’

‘Hopefully very soon.’

Chapter 2

1999

‘How do you feel?’

Mum’s words barely registered. For a long time, I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t. I was in too much shock.

And yet, at the same time, it wasn’t unexpected. When I was at school, I had always questioned why my parents were so much older than all the other parents. Other parents played sport with their kids at school barbeques, and every morning dropped off their kids at school on bikes, while mine saw specialists for osteoporosis. Once at parent-teacher night, my mum was mistaken for my grandmother. I had also questioned why I was the only kid at school without siblings. That was anathema during the 1970s and 1980s, and especially weird in large ethnic families. But I was everything to my parents and I looked enough like them to not question it.

My bottom lip quivered, uncertain of the new world in which I found myself. By contrast, Mum looked instantly younger. Part of that came through realising she’d broken the news to me first.

‘My biggest fear was if I died and never got to tell you,’ Mum said. ‘What you’d think of me the rest of your life.’

‘Yep,’ I finally said.

‘I’m not young anymore.’

‘You are, Mum.’

‘Ha,’ she smiled, ‘I’m not, I’m sixty-eight, but that’s okay. Is there anything else you’d like to know right now, any questions?’

‘No. Not right now.’

Mum paused; I don’t think she believed me. As it happened, I did have questions; dozens of them. But they were still ordering themselves in my mind.

In the end, Mum asked the most important thing that was on her mind: ‘Are you angry with me?’

I took a moment to respond. ‘No.’

‘We’re good? All okay?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh wait . . .’

Mum left the room and returned moments later with a thick photo album. It was heavy and dusty and smelled of leather and must, its pages stuck together like fused vertebrae. She flipped through the pages until she finally settled on a few photos. Careful not to tear them, she extracted three photos, and handed me one.

‘Here,’ she said, ‘your brothers. That’s Vasilios on the left, Georgios on the right.’

Looking at the image, I saw my own features. I had Billy’s eyes and ears and Georgios’s mouth and chin. The resemblance made my head hurt. It was as if my own face had been pieced together. I touched it lightly, just to make sure it was real.

Mum then showed me a photo of my biological father, Savvas. I saw a thin, moustached man staring out at me from beneath a slouched cloth hat. His image made less of an impression; I was, after all, familiar with the notion of a father. Despite being limited with both his knowledge of the world and his emotions, Dad had been a good father and I loved him dearly. He always provided for the family and as a child spoilt me with presents, which suddenly made a little more sense. I was, after all, a gift for him.

Finally, Mum showed me a photo of my biological mother, Anna. With a thick mop of wavy brown and pearly grey hair as if she’d been caught in a snow flurry, she shared a significant likeness with the sister-in-law who had raised me. I was pleasantly and instantly comforted. Mum was one and the same.

‘Wow,’ I mumbled, more to myself than anyone else.

Mum smiled warmly. ‘You can hang on to those,’ she said. ‘Maybe we can now finally put them in a frame all together.’ The album spine cracked as she closed it.

The afternoon had clearly been painful for Mum. The moist lines down from her eyes made her cheeks resemble a river delta. How she must’ve worried all those years that someone else had told me the truth before she did. It probably played on her thoughts every day. But now, she was overcome with relief, which brought me joy.

‘Who else knows?’ I asked.

Mum scratched her chin. ‘You mean, of our friends?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, all our old family friends do. I know I’ll always be grateful that none of them told you over so many years. I suspect they just forgot about it after a while. It was old news, and they knew I would one day tell you the truth.’

I felt a sudden urge to tell my friends the news of my brothers. And not just that: to call up my old school classmates, people I hadn’t spoken with in years, whom I didn’t even know the whereabouts of anymore.

The questions came at me. What were my brothers like? How did they feel all these years? What were their birthdays? What were their favourite foods, their favourite music? Did they dance? Sing? We probably didn’t even speak the same first language; my Greek was conversational, and their English may have been non-existent. Still, I wanted to shout it out, to tell everyone I had siblings. To tell them – hey, I’m suddenly just like you.

‘We’ll talk more another time,’ Mum said. ‘This has no doubt been a lot to process. For now, I think you should sit back and let the news sink in.’ She rose from the bed, extended her arms.

We hugged. Mum didn’t want to let go, still sniffing and leaving a wet salt imprint on the front of my sweaty shirt. It was the same loving hug of the mother that I’d always known. Warm, reassuring, laced with the smell of fresh laundry.

‘One more thing, Panagiotis,’ Mum said. ‘When you see your dad, give him a hug. He’ll be waiting.’

‘Sure,’ I replied.

I walked back to my study and flopped onto the battered office chair, which rolled backwards to a natural stop. I considered going for a walk to clear my head, which felt like it had been turned inside out. I thought about walking up to the mountain at the top of our street. I often walked there in the evenings to watch the kangaroos emerge and see the sun set over the distant Brindabellas. There was a calm dam that was immensely therapeutic to sit beside. But my neck was tense, my shoulders heavy, and I felt a sudden exhaustion wash over me. I wasn’t going anywhere. I sighed and stared blankly at the crooked piles of textbooks surrounding me, before closing my eyes. Left alone with my thoughts, my brain began to work, and the emotions started to flow.

In a flash, I made complete sense; a second later, no sense at all. I was no longer the person I thought I’d been my whole life.

But who was I now? Was I the product of some experiment? Whose life had I lived, who might I have been? And who might have been me?

I began to feel shock and confusion and anger – those who I thought were my parents were, in fact, my aunt and uncle. I felt deceived, and began to doubt. Was there anything else Mum was hiding from me? What else was untrue? They should’ve told me earlier, I thought. It would’ve been better to have grown up with this news, and always had it as part of my story. Then, I would never have had to endure this bloody agonising moment of truth.

Did my biological mother really give me up voluntarily? I found that hard to believe. What woman – what mother – could?

The next emotion to wash over me was sadness. It was at the realisation of having missed meeting my biological mother. I recalled a memory of a time she called our house and Mum asked me to come and speak with ‘an aunty in Greece’. I had refused, claiming there was no point talking with another distant relative I’d never actually meet; and if I did, I would probably never remember. That ridiculously immature attitude stabbed at me. I felt like a fool.

I snapped my eyes open and let them wander around the room, before settling on the wall above my desk. I saw a laminated photo of a football goalkeeper in mid-flight, an autographed band poster, a purple pennant from New York University, and an old exam timetable that I needed to tear down. Then my eyes drifted to a framed family photo taken when I was about seven. It was at a department store, in front of a fake blossom tree background. I was smiling innocently, joyously. So were my fake parents.

I thought about the mainstream view of family, of a heterosexual couple with biological offspring. Whether it was the inheritance of a business empire or corner store, blood relations were the basis of kinship and opportunity. Blood was where you came from and probably where you were going. And for ethnics like us, blood was everything. Family was everything.

But I had fallen through the cracks. I was adopted. I was an adoptee. Whose family did I actually belong to? I was neither here nor there, my blood was thin. ‘Here’ was nowhere I recognised anymore, and ‘there’ was an even stranger place I had never visited. I felt divided, my life torn in two: two families, but also two periods of time, the before and the after. The before became an illusion, a fallacy. While the after was a scary period of self-exploration in which I had already begun to question my identity.

Mum soon appeared in the backyard to tend her summer garden, which was bursting with plump tomatoes, crispy cucumbers, and jungles of basil and parsley. I watched her through the window move back and forth, more fluid than usual. Dad joined her not long after, picking ingredients for their evening salad. If they were talking about me, it didn’t show.

I looked back to the family photo, and started to make sense of the new world.

‘All the other kids were born here in Australia,’ I would say after I got home from primary school. ‘Mama, how come I was born in Greece?’

Mum would reply, ‘Because I wanted you to be born in Florina, in the same village as your dad and me.’

‘But you were here in Australia at the time, right?’

‘I was. But I flew back to Greece and had you there, then returned to Australia.’

Mum lied. She never braved a day’s worth of airline turbulence while pregnant as she claimed. Perhaps this was why Mum and her older sister, my aunt Soultana, occasionally slipped into speaking Turkish on the phone. They were talking about this.

I stared into the department store photo, into my father’s bright smiling eyes. Dad’s heart was warm, but always a degree colder than Mum’s. My whole life, I attributed this to the palpable distance that men put between each other, even their own sons. Now, I realised there was more to it. I wasn’t Dad’s blood at all – I was Mum’s.

Growing up, my identity had eluded me. Greek-Australian; what hyphenated beast was that? As a consequence, I had endured most of my adolescence trying to make sense of the world and how I fitted into it. At first, I had shunned my Greek heritage. Mum had forced me to speak Greek when I was younger, and sent me to Greek language classes and dancing lessons. I hated it all, and nearly died with embarrassment the day she made me wear a traditional tsolia costume with its kilt-like fustanella and pointed shoes. All I wanted to do was fit in with my Australian mates; to play cricket and footy and speak English. I found it hard to make friends. I often played games by myself, and also talked to myself, which made the other kids think I was weird. As the only brown-eyed, olive-skinned kid in my class, the only thing steeper than my learning curve was my accumulation of schoolyard bruises. My lack of siblings made me even more conspicuous. There was no bigger version of me to protect me. And if I ever fought back, reinforcements appeared quickly. At the end of the school day, Mum would laugh off my lamentations and say: ‘One day, God will gift you brothers!’

It seemed like such a throwaway line at the time. Little did I realise. The language, the culture, the comments. Secretly, it was all preparation for the future.

A loud knock on my bedroom window broke my reverie.

It was Mum, smiling. Ostensibly, she was showing me the biggest garden tomato I had ever seen, the size of a volley ball.

But I could tell she was actually checking to see if I was okay.

Chapter 3

1999

By the time I caught up with Dad, he was out the back in his homemade shed. Dad worked his whole life as a professional handyman, albeit self-taught. It’s what all Greek immigrant tradesmen were after the Second World War, there were no trade certificates then. Just an aptitude to work with your hands and a willingness to bend your back.

Dad’s shed was his kingdom. Growing up, I’d always feared it. The shed was next to a play area in the backyard where I once kicked soccer balls and smashed cricket balls. Every time an errant ball flew into the darkness of the shed, I had needed to summon all my courage to enter. The shed was shadowy and smelly and home to poisonous spiders and slippery rats and greasy car parts. Balls disappeared into the shed, never to be seen again. For some time, Dad parked his fishing boat there; to this day, I could still picture a large outboard motor sticking out of the shed like an ugly protruding tooth. Over time, Dad had extended the shed further and further back, building new sections of wooden framing, adding sheets of aluminium as he found them, until he finally reached the perimeter fence and stopped. Then he enclosed the entire structure, stuck on some makeshift doors, and filled it with every single tool or piece of building yard scrap he’d ever found. Twenty years later, the shed had become more hazardous than ever.

Dodging cobwebs and dangling wires, I approached Dad, who was hunched over his workbench with cigarette in mouth. I placed my arm around his shoulder and gave him a quick squeeze. I didn’t say anything. Dad looked up from the frayed electrical cord he was repairing with insulation tape and smiled. Mum briefly looked in through the doorway and I saw her smile, too.

Seeing Dad in his element suddenly made me realise why I’d never had an aptitude for manual labour. I suspect Dad would’ve loved to have passed on his labourer genes to his children. Instead, I turned out to be a myopic bookworm who didn’t know one end of a hammer from its Phillips head. Although that didn’t seem to matter to Dad who was always very proud of my academic achievements. And I respected his skills, too, whether they were carpentry or electricals or painting or car mechanics.

When I first wanted to buy a cricket bat, Dad said, ‘No, I’ll make you one’, and promptly went to his shed. He returned several hours later with a flat piece of wood in the shape of a cricket bat, which proceeded to stab my palms with splinters and send shockwaves up my arms with every cover drive. But his intentions were good, which was what mattered. Over the years, Dad built a fence out of scrap metal, a pergola from irregular bits of wood, and used leftover bathroom tiles to finish our mismatched shower recess. We always took pride in his work and ingenuity, though his craftsmanship was limited, everything he did had an organic quality about it, and a junkyard finish. But it was still more than I could ever offer. Although my future lay in a different direction, I knew that lab experiments would still require some level of dexterity and physical prowess, whether it was to prepare a chemical solution or dissect a mouse. I hoped I could handle it.

I found out two days later when I arrived at the Australian National University’s school of medical research. It was on the southern side of campus near an artificially constructed lake into which a murky creek slithered. Its stream was the cumulative refuse of half the city’s population. The pathology department pumped its cadaverous waste into the stream. Dogs and rats drowned in its muddy grasp.

I arrived at nine sharp on a Monday morning. It was the time the professor had told me to come. But then his secretary informed me that he was in California all week; a minor detail he’d forgotten to mention.

‘So what can I do this week?’ I asked her.

She looked at me blankly. ‘Not sure,’ she replied. ‘Can you read something?’

I ended up spending the whole day in a library study cubicle trying to make sense of two sheets of A4 paper. Onto them, the professor had scrawled symbols and text that mapped my upcoming four years of research. It had something to do with genes and mice and family trees and a lot of inbreeding. I wanted to bash my head against the cubicle’s walls to make sense of the notes but found the student graffiti too interesting, distracting. The professor probably wanted me to venture into the lab and get started on experiments, or at least learn a few techniques, but I was still too intimidated by the technicians and students and postdocs. They rushed across the white-tiled floor in their white coats and gowns, opening and closing white freezers, carrying small white boxes and white styrofoam coolers, working on white benches under white fluorescent lights. Magnetic stir bars rattled in beakers mixing solutions. Water baths bubbled. My nostrils flared at the smell of organic waste.

On the second day, I was reading the latest scientific journals, and focused on the articles about genomes and mapping DNA mutations. Most of them were from prestigious institutions in America: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia. The professor had only recently returned to Australia after many years as a successful immunologist at Stanford University. He had originally trained as a veterinarian but, like me, had been infected by the research bug and wanted to make great discoveries. His latest venture had been a large-scale mouse mutagenesis and gene mapping project. And I was his ‘guinea pig’, so to speak: the first student to take on a mouse mutant with an unknown gene at its core. I was both daunted and excited.

By the end of the week, I had secured a lab key and access card to the building from the security manager. My plan was simple. With the lab empty all weekend, I was going to stay until late and familiarise myself with my new surroundings. I opened drawers and freezer boxes and incubators, checking out the pipettes and monoclonal antibodies and bright red bottles of cell media. I couldn’t start any actual experiments; the mice were in another building with security access I didn’t yet have. Maybe I was hoping that if I sat in the lab long enough, the knowledge needed to cure the world of all disease would simply osmose into me.

When the professor returned the following week, we met to discuss my new mouse strain which harboured an unknown genetic mutation. The international rush to DNA sequence the genome of everything that moved, grew or was extinct was gathering steam, and I intended to stake a claim. The aim of my project was to analyse what was wrong with my mouse strain and map the mutant gene: the genotype. It was up to me to put meaning alongside the word in the genome dictionary that hundreds of supercomputers across the world were busily compiling. If it was something novel, my name would be forever etched within the dusty academic journals as the gene’s discoverer. It was scientific immortality. Maybe I would name the gene after myself. Maybe not.

An animal wrangler working in the animal facility had first noticed the visual characteristics of the mutation: the phenotype. She saw a stout, tennis ball-like rodent puttering around in the cage that didn’t look healthy. The animal’s back was hunched over, as if it was walking on its toes. But what the wrangler first thought was obesity or possibly oedema turned out to be something far more sinister: cancer. An examination of the animal’s siblings and offspring confirmed the same phenotype. The cancer was genetic. By examining the animal’s tissues and organs, I discovered the cancer was a leukaemia: an abnormal growth of blood cells seen in half the offspring with one mutant chromosome inherited from an affected parent.

‘A mouse with cancer often models the same disease in humans,’ the professor told me.

I was excited. My mouse strain offered the chance to understand the onset and progression of the disease in a living organism. Anti-cancer drugs could then be designed to benefit patients with the same genetic mutation. This was done by targeting the signalling pathway in which the mutant gene was active. I wanted to be a drug designer, I wanted to help people. I knew that part of this came from having elderly parents and spending much of my adolescence beside them in emergency wards.

I took some time to overcome my squeamishness working with mice. I found them understandably cute, especially the tawny brown ones, but would never admit it for fear of looking unprofessional. I saw the other lab members working without emotion so followed suit. I had soon developed enough scar tissue on my fingers to render me impervious to any further bites. It was as if I had earned my lab stripes.

The lab phone rang each time another sick mouse was spotted. The furry black tennis ball was the scientific equivalent of a call to arms. I changed into my powder blue overalls with matching hairnet and booties to prevent contagion. The mice were cleaner than any human. Scientists traditionally used cervical dislocation to euthanise small animals. By applying pressure to the neck, the spinal cord could quickly be separated from the brain, which provided a fast and painless death. But the immense volume of mice that the lab used for experiments meant this was impractical. Instead, the mice were placed in a clear plastic bag which was filled with carbon dioxide gas. I always felt uncomfortable seeing the bag balloon with the air of death. Despite the university providing numerous courses into the ethical treatment of animals, their correct handling and husbandry and euthanasia, I still hated having to do this, and wished there was a better way. But I always reminded myself that this was research meant to save human lives.

Using syringe needles to crucify the subject to a polystyrene mat, I doused it with ethanol for necropsy. I scissored open the swollen abdomen and carefully dissected the organs. The odious smell emanating from the intestines required a surgical mask, while the sight before my eyes was both horrific and beautiful. Lymph nodes, normally the size of sesame seeds, bulged like marbles in the cancerous mice. The spleen wrapped around and strangled the abdomen like a red hangman’s rope and the thymus filled the chest cavity, suffocating the pea-sized heart. The bone marrow, once a healthy crimson, was bleached a deathly white, smothered by leukaemic infiltrates. It was the dark power of Mother Nature through the modification of a single letter of DNA – a few atoms of carbon changed a C to a T or a G to an A. Given the complexity of the code for life, it was one in three billion possibilities. Incredible. Exquisite.

I carefully noted which number mouse was sick and where it sat within the large family tree that I was meticulously sketching. It was all about following the mutation, tracking its heritability. I was soon sticky-taping pieces of paper together as the pedigree grew in size with additional generations. Putting my notes to one side, I harvested the animal’s enlarged organs, cutting them free of its body. I weighed them on ultrasensitive lab scales, and then gooshed them into a single cell suspension using a stainless steel strainer. The rest of the day was spent centrifuging the cells, washing them with saline, and attaching a series of light-sensitive markers to the cell surface through a series of incubations. The markers were recognised by the facility’s cell analyser, a laser-propelled machine that distinguished cell types according to the fluorescence of the light-sensitive markers. What kind of leukaemia was it: B cell or T cell? Was it an early stage tumour or did it come from cells late in development? The panel of markers helped answer these questions. The cell analyser could run thousands of cells per second and count the number of cells in any tissue provided they were labelled correctly. It was painstaking work, though, which meant I wasn’t able to analyse the cells until the evening. But then, a fireworks display of cellular colour materialised before my eyes with each sample, thousands of tiny dots exploding onto a blackened computer screen in a windowless room in the facility’s basement.

It was only once an experiment was running smoothly that I could finally sit back and relax. The perishable nature of biological experiments permitted only certain stopping points; pull the pin early and the data was ruined, you may as well have not started at all. With the cells silently being analysed, I usually brought up a web browser and surfed the net. I often found myself entering the name of our family’s village into a search engine. In Latin, Florina meant ‘little flower’. Maps showed that it was closer to the Albanian capital Tirana than it was to Athens. Being so far north, Florina was perhaps the closest Greek township to the rest of Europe – thirty miles from Albania and just ten from the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. In some photos it was covered in snow, the rooftops and fir trees blanketed in white, the front of a Christmas card. It looked beautiful. I still couldn’t quite believe that this was where I’d entered the world, and that this was where I might’ve grown up if things had been different.

I threw myself at my work, driven by the incredible prospect of discovering a new cancer gene. For weeks, I worked through the night, subsisting solely on a vending machine as my food supply. I then returned home just before dawn to sleep a few hours, before getting up and doing it all again. As the nights got colder, I often returned home to find my pyjamas wrapped in a hot water bottle and left on my bed. I was young, brimming with energy and ambition, and saw the world as full of promise. I felt indestructible and thought everyone else in my life was too. So it came as a shock when I returned home one night to see spinning red lights illuminating the driveway. Mum was lying on a collapsible gurney.

Dad was standing nearby in his flannelette pyjamas and robe, a worried look on his face. ‘We’ve been trying to call you at work for an hour,’ he said.

‘An hour?’ I said.

I had been down in the basement all evening, analysing my latest tumour samples. The phone in the lab would have rung out two floors above. At that hour, there was no one else there to pick it up and come find me.

‘What the hell?’ I continued. ‘Did the ambulance take that long?’

‘We only just called it, after we couldn’t get hold of you,’ Dad said. ‘Mum’s been having chest pains.’

Chapter 4

1999

Irushed to Mum’s side. She wiggled her fingers at me in greeting, unable to speak under her plastic oxygen mask. I laid my hand on her shoulder and stroked her thinning hair.

‘You’ll be okay,’ I said. ‘Yes?’

She nodded numbly.

The paramedics lifted and positioned the stretcher into the back of the ambulance. The familiar metal clank of the adjustable gurney filled me with an uneasy feeling of dread. I saw my breath. The night was cold.

‘Ela,’ Dad said, ‘let me change and we can follow in the car.’

I reflected on the situation. It was usually Dad in the back of that ambulance with his unruly blood sugar and his nicotine addiction. Aside from the odd complaint, Mum was bulletproof.

I considered my experiments, my colony of mice, what they represented. The arrangement of their major internal organs was the same as any human, and they were 99 per cent genetically identical. But this specimen wasn’t another data point. This was a human specimen, aged nearly seventy years. This was my mother.

Dad and I drove through the night to the hospital in silence. The air in the car was tense and not conducive to conversation. Hospitals are the bookends of life. Those big white buildings where most people enter the world and so many depart.

With such elderly parents, I had become aware of the notion of mortality earlier in life than most other primary-schoolers, and grew up much faster than I would otherwise have wanted. By the time I was in high school, the emergency room was my second home. The most senior paramedics knew me by name, as did all the nightshift nurses. Behind a thin paper emergency department curtain, I sat in a stiff plastic chair worrying about my school exams and distressed about my parents’ health. It always seemed to be something different: a rapid heart rate, difficulty breathing, dizziness, numb body parts. And this was on top of accompanying my parents to a myriad of daytime medical appointments with doctors and specialists in order to translate for them. I approached it all with the same sense of duty as both an only child and a loyal son, but I knew these experiences had shaped my subconscious mind and eventual career choice.

Mum was taken straight in, hooked up, injected. I was soon sitting in the stiff plastic chair alongside her bed and together we waited for the doctors to complete their regime of tests: vitals, bloods, ECGs. Mum sat up in bed. Having been given several injections, she was now stable. She had removed her oxygen mask and changed into a hospital gown. On the floor beside her bed in a plastic supermarket bag were her slippers and clothes.

The late-night A&E freak show was in full swing. Angry men in open shirts and ripped jeans with bloody head wounds staggered past swearing at their police escorts. Comatose teenagers carried in for an urgent stomach pump were surrounded by a horde of delirious peers. Frantic mothers cradled young children, unsure of what they had swallowed when their backs were turned.

‘That’s the doctor there,’ Mum whispered to me. ‘See him? The man who walked past, the short one, he spoke with me earlier.’

‘Mm hmm,’ I murmured, overtired.

‘And that fat nurse over there took my blood. See my arm?’

‘Ooh yes. Bruised.’

‘She couldn’t find the vein.’

‘No good.’

There was a long silence, punctuated by a regular electrical blipping.

‘So, what else is new? How goes the work?’ Mum asked.

‘Good,’ I exhaled.

‘You haven’t been home much.’

‘Busy. There’s all this new stuff I have to learn.’

‘What are you doing?’

‘Experiments.’

‘Complicated?’

‘Yes and no. It’s messy. Stuff with mice.’

‘And you’ll be a doctor from this?’ Mum asked.

‘Yes and no,’ I said. ‘See all these doctors here? I’m trying to help them do their jobs, to understand what goes wrong in the body, and then design new drugs.’

‘For?’

‘At the moment, cancer.’

‘Poh poh!’

‘It’s not that exciting.’

‘But it is important. And plenty of money.’

‘Ha. Not really. Only for the lucky few.’

‘So long as you’re happy.’

Mum told me her only experience with mice in a medical setting was something she called pontikeleo, which loosely translated as ‘mouse oil’. In her village they would put baby mice in a small bottle of olive oil they later used to treat infections. The hairless mouse pups were naturally fortified with antibiotic agents on their hides. By placing them in oil, those substances were released, rendering the concoction as effective as an antibiotic. I was impressed. The village invention was ingenious.

‘Are your experiments like that?’ she asked.

‘Sort of,’ I replied. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘I’m fine now.’

‘But before there was . . .?’

‘Pain, heavy . . .’ She pointed. ‘Here, my chest.’

‘Down your arms as well?’

‘Not really, no. They gave me an injection in the ambulance. I’ve been fine since.’

‘Probably stress.’

I tried to reassure Mum, although I imagined her life had significantly de-stressed since telling me the news of my adoption. It was as if a twenty-five-year weight had been lifted. Then again, people often got sick after stressful periods. I knew I often did when my exams were over. When the body’s defences to ward off inflammation or infection during a period of stress phased out, a letdown reaction occurred. Stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline were released, and illness followed.

‘Your dad,’ Mum said, ‘he drives me crazy sometimes.’

‘I know, I know. But let the doctors finish all their tests, see if it’s anything.’

‘Endaxi.’

There was another long silence. I tried to let out my tension with a long sigh. Mum chastised me.

‘I told you before, don’t do that,’ she said. ‘You’re still too young to sigh like that.’

I shifted in my seat and looked away.

‘So what are we waiting for now?’ Mum asked.

‘The second blood test,’ I replied. ‘They’ll come take more blood, then take it away.’

‘Ah.’

The midnight ward looked like a black and white cartoon, no soft contours or sense of optimism. With the footsteps of every approaching physician, I prepared for the worst. I imagined an advanced infection, a catastrophic rupture, an irreparable blockage, a malignant tumour.