Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Heliotrope Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

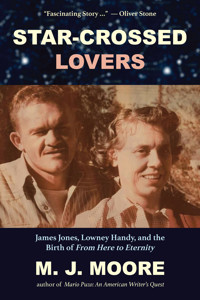

From Lowney Handy's scandalous small-town open marriage to author James Jones's extraordinary apprenticeship with Maxwell Perkins (legendary editor of Hemingway and Fitzgerald), Star-Crossed Lovers illuminates an unforgettable love story. She was an eccentric small-town self-taught rebel, driven by creative zeal and a non-conformist streak. He was a distressed ex-GI (flat broke, without prospects, damaged by war), 17 years younger than she, consumed by visions of a writer's life. Lowney and her husband invited Jones to live and write at their home in Robinson, Illinois. Many years of struggle ensued. In the end, Jones's From Here to Eternity won the National Book Award and profoundly transformed American literature. The 1953 film adaptation swept the Academy Awards in 1954. Expanding their shared vision of life, the Handys and Jones incorporated a unique writers' colony in 1951 that was funded mostly by Jones's Eternity royalties. This is their odyssey of love, passion, and conflict, which remains exceptional in literary history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Star-Crossed Lovers

“In today’s age of flimsy comic-book characters passing for superheroes, it is life-affirming—hell, it’s vital—to recall the red-blooded humanity James Jones poured into his 1951 National Book Award-winning From Here to Eternity. How the semi-autobiographical novel made its way before an eager public provides much of the spine of M. J. Moore’s enlightening Star-Crossed Lovers . . . but the narrative offers so much more. At its core is an iconoclastic love story that provides further ammunition to Jones’s recurring theme of the individual versus society—all of which Moore soundly spells out in engaging and impressively researched detail.”

∼ STEPHEN M. SILVERMAN, author of David Lean; The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America; and Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies

“You have an enviable ability to diffuse each paragraph with an extraordinary amount of information—and still retain lightness.”

∼ KENNETH SLAWENSKI, author of J. D. Salinger: A Life

“Oh, to be young and a writer and finding your way with an exotic older woman! M. J. Moore’s Star-Crossed Lovers is an incredible tale of James Jones, his novel From Here to Eternity, and the years he spent under the spell of his lover, Lowney Handy. Indispensable!”

∼ LUCIAN K. TRUSCOTT IV, author of Dress Gray, Heart of War, and other novels; Village Voice staff writer; Class of ’69 West Point graduate

“I did read Star-Crossed Lovers with great interest. Fascinating story—kept my interest throughout. My congratulations to you . . .”

∼ Oliver Stone, Academy Award-winning writer/director of “Platoon,” “Born on the Fourth of July,” “JFK,” and other films; author of the novel A Child’s Night Dream and the memoir Chasing the Light; and Purple Heart veteran of the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Division

Star-Crossed Lovers

Other Books by M. J. Moore:

For Paris, With Love & Squalor

Mario Puzo: An American Writer’s Quest

Copyright © 2023 M. J. Moore

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage or retrieval system now known or hereafter invented—except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper—without permission in writing from the publisher: [email protected]

ISBN 978-1-956474-21-3 paperback

978-1-956474-20-6 eBook

Cover Design by M. J. Moore and Naomi Rosenblatt

Typeset by Heliotrope Books

Unless otherwise credited, all photos are public domain from varied online archives.

In memory of Joan Didion Dunne and John Gregory Dunne, with gratitude . . .

and for Mary Tierney, with love and appreciation.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Boyhood Struggles

Chapter 2: You’re in the Army Now!

Chapter 3: G. I. Blues & Pearl Harbor

Chapter 4: Summer of ‘42 & Guadalcanal ‘43

Chapter 5: The Woman ∼ Lowney Handy

Chapter 6: Going to Meet the Man ∼ Maxwell Perkins

Chapter 7: Faith Like Mustard Seeds

Chapter 8: Rising from Their Ashes

Chapter 9: “ . . . a startling enigma to this day . . . ”

Chapter 10: Jones, Lowney, and Their Writers’ Colony

Chapter 11: “The Most Famous Book in the World”

Chapter 12: Transitions Galore

Epilogue

Afterword

Notes of Gratitude

Bibliography and Other Sources

About the Author

INTRODUCTION

Star-Crossed Lovers is the story of two unique individuals: James Jones had a mercurial personality; Mrs. Lowney Handy was as idiosyncratic as her name (which rhymes with Tony). Both of them were volatile. Gifted, stubborn, and intense. Sometimes volcanic.

Novelist James Jones, in his youth, is this story’s “through line” —up to a tipping point. The moment Lowney Handy appears, Jones’s life becomes a shared narrative. Together, with devoted assistance from others, they made a significant contribution not just to American letters, but to world literature: the National Book Award-winning From Here to Eternity.

When they met on the weekend of his 22nd birthday in 1943, Jones was an AWOL combat veteran, plagued by an alcoholic upbringing compounded by Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He’d survived the attack on Pearl Harbor; and he’d been wounded at Guadalcanal in the war against Japan. Jones was an embittered, hard-drinking, angry young man. She was a creative, spiritual, self-educated maverick devoted to helping troubled renegades.

Meeting 39-year-old Lowney Handy (childless, with a boldly unconventional marriage) in 1943 was more than lucky for Jones. It was a life-transforming benediction, especially by the time she turned forty in April 1944.

Lowney Handy advocated for Jones’s “medical discharge” in the summer of ’44, when the Army was prepared to court-martial him. It was Lowney and her husband with whom Jones lived full-time, at their mutual invitation; and Jones often traveled with Lowney as she (more than anyone else) coaxed out of him what became From Here to Eternity, between 1946 and 1950. Expanding their shared vision of life, they inaugurated a unique writers’ colony, legally incorporated in the State of Illinois on September 21st, 1951. Supported annually almost wholly by Jones’s earnings from Eternity (in 1952 alone, he gave $65,000 to the Handy Writers’ Colony), dozens of writers attended the Colony in the 1950s. Aside from writing priorities, Lowney and Jones practiced Yoga, meditation, breathing exercises, and macrobiotic diets; they studied Hinduism, Buddhism, and American Transcendentalism. And from 1943–1957, they sustained their tempestuous, trans-generational love affair.

In this book, James Jones’s youth unfolds, from childhood to the Army, setting the stage—until he collides with Lowney Handy, as he did in November 1943.

Then, it becomes the Jones and Lowney story; with critical allies ranging from her husband, Harry Handy, to the dean of American book editors: Maxwell Perkins at Scribners in New York.

Art and alcoholism, war and PTSD, Max Perkins’s and Scribners’s, visions of The Great American Novel, an open marriage in small-town Illinois, plus immersions in studies of the religions of India and the Far East—all that (and more) induced From Here to Eternity, which exploded like a nova in 1951.

Challenging questions arise. For example, how did Jones’s anti-authority, profane, blistering portrait of the U.S. Army win the National Book Award not only at the height of the McCarthy Era, but at the peak of the Korean War in 1952? Has any other debut novel ever conquered our culture in such a way? The novel From Here to Eternity was both critically acclaimed and a blockbuster popular success, despite evocations of adultery, binge-drinking, prostitution, homophobia, anti-Semitism, hazing in the military, hypocrites hiding behind officers’ rhetoric, and racism polluting the ranks and society at large. Oddly, Eternity’s phenomenal success dovetailed with Eisenhower’s election to the presidency, defying cliches about America in the 1950s being an uptight society of Silent Generation “squares.”

This is the true-life love story of Lowney Handy and James Jones, with its mythological, fateful arc. After he married Gloria Mosolino in 1957, the remainder of James Jones’s life and career became another story, and belongs properly to another book. The Jones and Lowney odyssey is exceptional in literary history.

She was an eccentric small-town autodidact driven by creative zeal and fueled by her blazing non-conformist streak. He was a distressed ex-GI (flat broke, without prospects, damaged by war) who obsessed over his hunger for a writer’s life. Some of their unpublished letters are in the Handy Writers’ Colony collection at the University of Illinois (Springfield). Quotations from their letters enhance this book.

In the early life of author James Jones, all roads led to Lowney Handy. And Jones’s unorthodox long-term love affair between 1943 and 1957 with a childless, married, older woman (17 years his senior) in downstate Illinois . . . that is the ultimate focus of Star-Crossed Lovers ∼ James Jones, Lowney Handy, and the Birth of From Here to Eternity.

1

EARLY STRUGGLES

The last words he was supposed to have said were, “I’ve left you all well-provided-for.” The Crash was not long in coming.

∼ James Jones, “The Ice-Cream Headache”

When author James Jones wrote short stories based on his childhood, he often exhumed conflicts and anecdotes illustrating his parents’ distress.

In his story “Just Like the Girl,” Jones dramatizes upsetting incidents that he experienced before he was ten years old. His alter ego in the story is John Slade. Similar to how Hemingway deployed his youthful doppelganger, Nick Adams, in a number of short stories, the character of John Slade serves as a stand-in for Jones; allowing the author to discharge a large amount of autobiographical grief through the crises endured by his protagonist. Tense family despair and rage are palpable.

The livid mother in “Just Like the Girl” is convinced that her alcoholic husband is having affairs. She makes no secret of her suspicions and fear. Most of all, she leans on her young son, and confides her dread quite inappropriately. Finally, she creates a new level of mother-to-son tension when ordering the boy to hide in the backseat of her husband’s car, on the assumption that when he drives off after dinner, the husband will surely be en route to an assignation with a floozy. Persuading her younger son to spy on his father, whom she assumes will later return home drunk, is not the worst thing to happen in this story. What’s worse is that the mother conveys her requests in a way that causes young John Slade to think that he must do her bidding, to prove his son’s love for her.

It is a story so stark in its evocation of childhood despair that one editor, in particular, recoiled. Jones remembered: “I once showed [“Just Like the Girl”] to a newspaper editor in my hometown of Robinson, Illinois, who had known and admired my mother. The strange, guilty, upset, almost disbelieving look on his face when he handed it back, which seemed to say: ‘Even if it’s true, why do it?’ was worth to me all the effort I put into writing it.”

One answer to the question—“Why do it?”—is deceptively simple, yet it’s the key to understanding the lifelong odyssey James Jones undertook as a postwar author. To answer that question in one word: Honesty.

That was, at bottom, Jones’s ultimate intention as a writer. Whether composing a chapter to one of his capacious novels or writing a short story, crafting a passage for his nonfiction World War II chronicle or noting details about America’s exodus from Vietnam (which he covered for The New York Times Magazine in 1973), he held to a rigorous code of narrative integrity; always writing as honestly as possible.

Poet, novelist, and biographer George Garrett, in his 1984 book James Jones, writes that “Jones was always a truth seeker and a truth teller. [He] has left a good record of his own mixed feelings about himself and his youth. If we turn to the evidence of the John Slade stories published in The Ice-Cream Headache, stories Jones claimed as autobiographical and that tend to conform to the known details of his youth even while adding more information, we discover other characteristics and other forces at work within him . . . we are presented with a more complete picture than anywhere else of the family, a ‘Faulknerian’ family. In letters, in interviews, and in some of the best of the stories collected in The Ice-Cream Headache and OtherStories,there is strong evidence of the conflicts and contradictions . . .”

Jones had despondent parents. His small-town dentist father, Ramon, was an alcoholic whose unsteady hands caused some patients to seek treatment elsewhere. And Jones’s mother, Ada (once considered a great beauty in her youth, prior to marriage and motherhood) suffered from diabetes exacerbated by depression and obesity. Ramon and Ada named their first child George, but he was always called Jeff. Born in 1910, Jeff had no siblings until James Jones was born on November 6, 1921; followed by the birth of Mary Ann Jones in 1925.

Worn down by life’s disappointments, both Ada and Ramon were melancholy.

Jones’s memories of his youth were visceral. Describing himself as a child, he highlighted that he was “a shy kid with glasses.” Such a casual remark conveyed something more about why Jones felt awkward and insecure as a young boy.

Having an alcoholic father who is unhappily married to a woman plagued by chronic discontent could make any child feel anxious, worried, and perhaps guilty for lacking the capacity to make the parents happy. But in Jones’s case, his poor vision and the serious need for glasses in his youth set him on the path that led to his career. Conversing once with interviewer Leslie Hanscom, for a piece entitled “The Writer Speaks,” Jones confirmed this. Inquiring about how Jones segued from soldiering to writing, Hanscom said: “You’re somebody who appears to be designed by nature to exert physical strength. Yet you have undertaken to pursue the four-eyed profession of writing. What happened?” Jones replied that the trajectory of his life was, indeed, partly the result of being “ . . . as you said, four-eyed. I think it was because I had to wear glasses when I was little.”

Jones’s poor vision as a child was matched by his physical frailty. A small boy, his short stature was exacerbated by the way his large ears stuck out on a head that seemed too big for his body. Unlike his older brother Jeff, who filled out early and had natural gifts as an athlete, Jones was never able to achieve any real competence in team sports, although he tried in every way to engage in athletics as a means of demonstrating his feisty spirit. Plus his courage. As often as not, he tried too hard and that usually resulted in more frustration for a gawky boy, whose own father kidded about him. Ramon joked that with his large head and big jug ears, Jones resembled an automobile with both its doors wide open. Jones felt that he always had to compensate for a slight physique, small hands, and eyeglasses. Perhaps to rebel against the idea that he was compromised by wearing glasses, he vigorously participated in everything all the other neighborhood boys were up to: snowball fights, war games, different sports, and plenty of pranks.

At home, Ramon taught both of his sons the rudiments of boxing. Rather than take it easy, Ramon punched hard enough to knock Jones down. And instead of complaining or crying out, Jones reacted with vehemence. He determined early on that the best strategy was to fight as aggressively as he could, no matter what.

* * *

With her older son Jeff gaining his independence more and more as the 1920s reached their end and with her only daughter, Mary Ann, receiving the favored treatment that’s sometimes enjoyed by the baby in the family, Jones as a middle child caught the brunt of Ada’s worsening moods. Once, as a neighbor looked on, Ada smacked Jones harshly across the face. The impact of such a blow to a sensitive child can be devastating. And there were other blows, as well: Jones was whacked with broomsticks and at times chained to a backyard post, so he would not roam while Ada did chores.

One of the earliest photographs of James Jones shows him riding a tricycle. His oversize head and wire-rimmed glasses are highlighted by the way his jaw is thrust forward. He steers the tricycle like a race car, with a posture and an attitude that signifies determination. Childhood friends recalled, many decades later, how speedily and relentlessly Jones rode down the sidewalks of Robinson on his red tricycle, darting past anyone and everyone in his path.

And yet, another side of young James Jones emerged before he entered high school. As is often the case with children who absorb the antagonism and turmoil exuded by combative parents, Jones cultivated the solitary side of his personality. There was an attic in his home and he often retreated up there to play with a variety of toys, especially traditional sets of toy soldiers and figures of Arthurian knights. More than toys, however, there was the paramount presence of books.

Ramon Jones knew that his father (a prominent local attorney) self-published a small book called The Trials of Christ: Were They Legal? in 1922. Patriarch George W. Jones composed that book to present compelling legal arguments proving that the Roman authorities flouted their own laws in persecuting Jesus. Throughout Ramon and Ada’s home, stacks of books were shelved. Jones was known in the neighborhood for asking any guest who visited the house to read to him; and he amazed visitors by complaining when a passage was omitted. Jones’s extraordinary memory was a feature of his personality that never diminished. He had vast powers of recall throughout his life.

A Carnegie Library near Jones’s boyhood home, and its staff, had a tremendous impact on the growth of the future author. In addition to furnishing an inventory of books that filled his imagination with visions of heroic adventures, the library provided him with a safe, quiet sanctuary within which his mind and spirit were unencumbered. In the library, all domestic strife dissolved.

Early on he obsessed over P. C. Wren’s war trilogy Beau Geste, Beau Sabreur and Beau Ideal. Jones once said that he had re-read each of those French Foreign Legion narratives “at least twenty times; and I knew all of their characters; and each character’s big scenes.”

One librarian, Vera Newlin, became a teacher and guide for Jones. She retained all her life a vivid singular memory of when she first encountered him: “As a little boy coming over to the library,” she explained to interviewer J. Michael Lennon. “He was always very eager to get there.” When asked how old he was at the time of their initial encounter, Vera Newlin said: “Oh, riding a tricycle! My first memory of Jim is on a tricycle riding back and forth in the neighborhood. And he always had his jaw stuck out like he was just expecting somebody to hit it.”

It was not too long before young Jones’s exceptional curiosity and precocious intelligence were apprehended by Vera Newlin. She shepherded him through the children’s library, time after time, helping to introduce him to writers and stories that are that were enshrined as so-called “boys’ books”: Kidnapped and TreasureIsland and other works by Robert Louis Stevenson; the stories of Rudyard Kipling (whose lines of poetry would later provide Jones with titles and epigrams for FromHere to Eternity, The Thin Red Line, and Go to the Widow-Maker); the novels of Charles Dickens, and others. Vera Newlin quietly exempted Jones from the rules and regulations separating the adult shelves from the children’s inventory in the basement; and the shy, quiet, bespectacled boy was allowed to not just browse but to check out almost any title available. “He had a number of exceptions made for him,” Vera recalled. “You couldn’t help but like him. You could get aggravated at him, but you would like him. “

Vera Newlin ascertained some of Jones’s boyhood distress while mentoring the bookish youngster in the Carnegie Library throughout his early years in Robinson: “His mother was older than I was, but we played cards in the same circle. She was a complainer. I shouldn’t say that. But she was. He had a feeling that his mother liked his older brother much better than she liked him. And then there was the sister. Jim felt like he was the outcast.” When reflecting on the favoritism that she detected in the dynamics of the Jones family, Vera concluded: “Jim always had a feeling, I think, that his [parents] didn’t like him as well as they did the other kids.” The rapport between Jones and Vera, the instructive reference librarian, was highly beneficial.

Annis Skaggs Fleming was a fellow student with whom Jones became friends at Lincoln Grade School. She clearly recalled the way Jones was allied with Vera Newlin, whom she remembered as “ . . . a lovely person. Strict. She kept a good library and you could go there to study; you could go there to explore. And she gave him directions [about] books he should read. She kept telling him: ‘Now Jim, you should read this; you should read that.’ And he followed. And he kept up!”

Ruminating many years later on the earliest part of his life, Jones spoke warmly of the Carnegie Library, concluding: “It had a great deal more to do with my becoming a writer than I had any concept of at the time I was reading there.” One of Jones’s future allies, fellow author James Baldwin (who was also born with the name James Jones, but then renamed Baldwin after his mother remarried), experienced a similar rite of passage due to his immersions in the Public Library in Harlem.

What Baldwin recalled about that library’s effect on him resembles what Jones had experienced. In the documentary film The Price of the Ticket, Baldwin says:

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world. But then you read. It was books that taught me [that] the things that tormented me the most were the very things that connected me to all the people that were alive; who had ever been alive. I went to the 135th Street library at least three or four times a week. And I read everything there; I mean every single book in that library. In some blind and instinctive way, I knew that what was happening in those books was also happening all around me. And I was trying to make a connection between the books, and the life I saw, and the life I lived. I didn’t know how I would use my mind or even if I could. But that was the only thing I had to use.

Books fed Jones’s hunger for imaginative diversion and vivid dramatic engagement. As he progressed through elementary school, his passion for reading remained his main defense against the distress of his increasingly unhappy home.

* * *

The summer of 1929 was a particularly unhappy time. George W. Jones, the autocratic, temperamentally frightful paternal grandfather whom Jones adored and whom Ada resented and before whom Ramon always felt shrunken and feckless, died at the age of seventy-one. The loss of this towering figure of stability, success, and fiscal potency was ominous. The following October, between so-called “Black Thursday” (October 24, 1929) and “Black Tuesday” (October 29, 1929), the stock market imploded. Robinson’s first casualties were those whose big money had been fast acquired after oil was discovered on private properties, like the farm land owned by George W. Jones. For the Jones family, the fallout from the stock market crash worsened badly over time.

Another nagging problem at the start of the Great Depression was that clients for Ramon’s dental practice were fewer. This diminished Ramon’s income a great deal, which increased Ada’s anger, bitterness, and contempt.

She became a more forbidding figure to her second son, whose older brother Jeff had parlayed his excellent high school grades, athletic prowess, and yearbook status as Most Popular Student into a successful getaway from the toxic Jones home. Jeff had already left for college before the death of his grandfather or the collapse of the stock market in 1929, and he was twenty-four years old when James Jones entered eighth grade in the fall of 1934. Jeff was spared the worst of his family’s tumultuous convulsions, which worsened in the early 1930s as the Samuel Insull Utilities Investment Company collapsed, devastating over one million shareholders. It was with Insull’s seemingly invincible stock that George W. Jones invested (on behalf of his heirs) all the profits from his law practice and oil earnings.

Everything was wiped out. Dividends, stock portfolios, trust funds, and annuities dissolved overnight. The family fortune was lost. The heirs of George W. Jones were suddenly without any financial cushion. Their social status nosedived.

In those same years, Ramon’s dental practice continued shrinking. He took to bartering with patients, instead of turning them away. But bartering was hardly a substitute for a positive cash flow, and the deepening Depression years shredded what remained of the little confidence and self-esteem Ramon had ever had.

It was necessary now for Jones to wake daily, always before dawn, and earn money delivering newspapers. By the time Jones was a seasoned newspaper carrier, his behavior in school and in public was increasingly belligerent. Cantankerous at times. Obnoxious in some ways and rude in others.

In his final years at Lincoln Grade School, it became clear that Jones wouldn’t follow in the much-admired footsteps of his older brother, Jeff, whom the yearbooks celebrated as being the most popular of students; also for his athletic achievements and school spirit. Going to the opposite extreme, Jones would later tell his brother that his own personal goal at Robinson High School was to succeed at being “considered [the] class prick.”

He also entered adolescence with an entirely different home life than Jeff had known in the family’s better days. Jones later wrote to his editor at Scribners about the contradictory perspectives the two brothers cultivated as young men: “[Jeff] grew up before our family lost its money and its social position, whereas I came along 12 years later and was forced to fight for my pride from the first time I entered school.”

One of his high school yearbooks highlighted his reputation for brawling and for dozing off in classes by describing him as “a scrapper” and “a napper.”

Even in an era that did not consider “putting up your dukes” taboo, Jones had a titanic reputation for raising hell. On one occasion, he lost control and ended a fight on the street by shoving a boy through a plate-glass window.

Mortified by his act, he was confused and petrified. He immediately ran to the downtown bowling alley, where he knew he could find his father. By this time, with his dental practice floundering and his dependence on booze increasing badly, Ramon Jones was spending more time imbibing than he was at the office. But on this occasion, Jones recalled that he still came through in a protective, loving way.

Jones explained to his father what had just happened. And later he recounted that although his father “was half [drunk], he got right up and went back across the street with me and took the whole thing on his shoulders and got it straightened out. I’ll never forget that. It’s a fine thing for a boy to have someone who is rather like a rock to his small intellect, someone who will always be there when needed.”

One healthy means by which Jones channeled his aggression in those years was in boxing. Having learned the rudiments of the sport from his father at home, Jones was well prepared to accept the invitation of Si Seligman to train for the Golden Gloves competitions in Terre Haute, Indiana (40 miles east of Robinson).

Si Seligman owned and operated the newsstand on the Square downtown where Jones appeared on his bike at five o’clock every morning. He earned Seligman’s trust because he held the job for years. The job’s toughest requirement was to arrive every morning before sunrise, in order to sort out the newspapers from Chicago, Indianapolis, Robinson, and Terre Haute. In all those years on the job, Jones was never late and never missed a day, despite the frigid Illinois winters.

Si Seligman inevitably observed Jones’s steadfastness, and he recruited him to box with every intention of entering him in Golden Gloves bouts. Seligman was a coach figure whom the local boys respected.

Jones enjoyed his first Golden Gloves fight in neighboring Terre Haute, winning solidly be decision. In a subsequent bout, he surprised the judges and Si Seligman by not really trying all that hard. He seemed to let the other fighter win by default. When asked about why he let himself slide, Jones said that he didn’t really feel like hurting the other guy. Perhaps he was just exhausted. The yearbook’s quip about Jones being “a scrapper” and “a napper” made light of his dozing in mid-day classes. But his daily job at the newsstand impelled him to rise at four-thirty, in order to bike downtown by five in the morning. Sleep deprivation must have been onerous.

Jones was bored in most of his classes and by nearly all of his teachers. His own reading habits remained encyclopedic and robust, while rote learning anesthetized him. The strict protocols of classroom behavior in the 1930s—sitting passively and taking notes while the teacher lectured up front—did not capture his imagination.

Most distressing in Jones’s life as a high school student was the insecurity of the family’s finances, as the Great Depression metastasized. Following the collapse of the Chicago-based Insull company (a utilities empire), it was necessary for Ramon and Ada to sell their house on Main Street. They become renters. More than once in the first half of the 1930s the Jones family had to relocate (making very public moves in a small-town where everybody gossiped) to another rental property; each time to a house that that was a bit smaller, a little shabbier, on a street that was more run down than the one last one. This decline in fortunes devastated the status-conscious Ada, and ensured that Ramon drank even more, while his dental practice gradually diminished.

If Jones as a teen suffered any symptoms of depression amid such tension, then everything was worsened by the hormonal hurricanes endured by boys of fifteen and sixteen and seventeen.

* * *

Just before Jones began his sophomore year at Robinson High School, he surely saw the August 10, 1936, TIME Magazine that featured on its cover a writer who in that season was commanding the attention of the world: John Dos Passos. It would have been inconceivable for Si Seligman’s newsstand on the Square in downtown Robinson not to stock TIME(soon to be joined by its successful sister publication: LIFE). Those magazines were windows onto the world. And if Jones read merely the first two paragraphs of TIME’s cover story on John Dos Passos, he may very well have had his first inkling of how powerfully engaged with his contemporary world an American author could be. TIME proclaimed:

Old history is in books and new on front pages. Yet neither tells the whole story of a people, a period, a place. Behind the extraordinary news in the papers, the decisive events described by historians, lies a mass of anonymous, miscellaneous human happenings, comprising the routine stuff of daily living. This is private history, and, though it rarely gets into public history, it outweighs soldiers and statesmen, battles and booms, in the final balance of time.

To relate these minutiae of contemporary experience to the broad sweep of historical developments has been the task, for the past ten years, of a novelist named John Roderigo Dos Passos. Last week Author Dos Passos, 40, offered readers a novel called “The Big Money” that stood midway between history and fiction, the last of a series of three books that constitute a private, unofficial history of the U. S. from 1900 to 1929.

TIME’s cover story on John Dos Passos highlighted not just the completion of the innovative author’s U.S.A. trilogy, but also the notion of a living novelist being at the center of American culture. Other articles in TIME (and LIFE) described a world hell-bent on another global war, one that would affect James Jones as profoundly as the Great War affected John Dos Passos. Meantime, Jones was at war with himself.

There was no one with whom he could share his thoughts about the demise of his family. Guidance counselors were not in vogue in that era, so at Robinson High School he did not have a confidante. His mother’s Christian Science bromides did not in any way comfort him. Ramon’s lack of stability worsened through the years and though he might rise to the challenge of the occasional crisis, in general he had become a pathetic figure. No priest or doctor or clergy of any kind was relevant, and though there were a few teachers who now and then noted Jones’s potential, he was so indifferent to his studies (most of the time) that he was, by and large, tolerated; yet not truly comprehended or attended to. He craved authentic attention.

A ferocious desire to escape Robinson rose up in Jones as a teenager. His vivid imagination was rarely invited to express itself in coursework at school, but that did not prevent him from using that imagination to vent in his own way. Fueling his dreams were the shame, insecurity, rage, and confusion he felt about his own life.

Money was not just tight in Jones’s household; it was scarcely available. Brand new clothes were rarely bought and the prospects of any future financial recovery were remote. Jones’s moodiness and his behavior revealed his furious discontent.

His anger led to a new awareness of the importance of repressing his feelings—shielding both himself and others from the volcanic emotions he felt. He vowed to master the ability “never to tell anyone the truth about any of the things that were important to me.” In his future writings, this trait would be personified, again and again, by his male and female protagonists; many of whom struggle with the issues of either repressing one’s private thoughts or harboring secrets.

With so many legendary stories committed to memory (Jones never lost his appetite for books, not even at the peak of his tumultuous adolescence) and reams of heroic narratives re-read continuously, it is no surprise that the teenager who was an autodidact in World Literature would day-dream so feverishly about escaping from Robinson. On more than one occasion, he literally tried to do so.

“I would sneak off and take refuge in my secret ambition to run away and join the Foreign Legion as an adventurer,” Jones later admitted, wryly alluding to his endless preoccupation with the Beau Geste trilogy.

When not immersed in his imagination, Jones sometimes tried to walk off into the sunset in his own way. On one occasion, he headed due north in an effort to walk his way to Chicago. He was two miles down the road when he was retrieved and returned to Robinson. His escape was deferred.

Mediocre grades defined Jones throughout high school. His report cards were mostly splattered with Cs and Ds. Only in two English classes did Jones come alive, and in one case it was an issue of having a crush on his teacher.

“I was of course in love with her,” Jones fondly reminisced, when speaking of the twenty-four-year-old woman who was his English instructor during freshman year. “She liked me, and loyally set out to make a reader of me, only to find that with the exceptions of Shakespeare and Joyce, I had very nearly read as much as she had (including Hemingway and Fitzgerald) without knowing any of these people were ‘writers,’ simply because my father had the books around.” The attractive teacher had been taken in as a lodger by Ada Jones (a common practice in hard times), and Jones’s libido was galvanized: “I would hang around the upstairs hall,” he confessed, “trying to catch a flash of thigh or panties or breast. She was very nice about this though I’m sure it embarrassed her.”

Less than a decade later, Jones’s life would be forever transformed by another older woman with whom he would experience a profound and complicated rapport.

Another dimension of Jones’s passion was evoked throughout his junior year, when Harriet Hodges, his English 3A teacher, regularly asked her students to engage in vigorous discussions about literature. This was the first time Jones experienced the opportunity in class to express any personal reactions or emotional responses to assigned readings. He had a knack for effectively reading literature aloud (a gift that later made his Caedmon Spoken Arts album superb) and in Hodges’s English class, Jones spent his junior year vividly participating, and also thriving as a class leader.

“I was at a peculiar stage of my life,” Jones later explained, “where I was getting a great charge and a great emotional release out of writing openly fictional themes (always derivative of some book I’d just read, naturally) for her English class. Attacked in class by what I now realize were several jealous straight-A plodders, I was defended by this lady who told me to keep right on and added that all writing was not necessarily the cataloging of summer vacations.” Once again, an intelligent and sympathetic older woman affirmed Jones, and by doing so inspired him greatly.

* * *

His senior year of high school (1938–1939) unfolded against a national and international backdrop of one grim historic milestone after another. Throughout 1938, Hitler was in the news with morbid frequency. The Third Reich cast its shadows everywhere. In the January 2, 1939, issue of TIME magazine, the Man of the Year was announced. It was hardly an occasion for celebration, as TIME reluctantly noted:

He had torn the Treaty of Versailles to shreds. He had rearmed Germany to the teeth—or as close to the teeth as he was able. He had stolen Austria before the eyes of a horrified and apparently impotent world.

All these events were shocking to nations which had defeated Germany on the battlefield only 20 years before, but nothing so terrified the world as the ruthless, methodical, Nazi-directed events which during late summer and early autumn threatened a world war over Czechoslovakia. When without loss of blood he reduced Czechoslovakia to a German puppet state, forced a drastic revision of Europe’s defensive alliances, and won a free hand for himself in Eastern Europe by getting a “hands-off” promise from powerful Britain (and later France), Adolf Hitler without doubt became 1938’s Man of the Year.

To imagine Jones in his senior year of high school is to see a young man who in no way felt at home with standard classroom protocols, looking out upon a world that was spiraling toward another international conflagration. With the exceptions of the two English classes he’d enjoyed, high school was a wasteland for Jones. He collected Cs and Ds in his senior year, and later concluded that his speedy, accurate typing skills of 55 words per minute were “probably the only thing of value I garnered out of my high school career.” If he had any fond memories of the activities he signed up for along the way (he tried the Latin Club; sang in the Mixed Chorus; played trombone in the band; and also performed in an operetta), Jones never said so publicly. But his typing skills proved invaluable.

Equally invaluable was his ability to apprehend “the truth of Imagination,” as poet John Keats eloquently put it.

No matter how disconsolate Jones was about his family’s lack of money or the fact that after selling their home on Walnut Street and renting on King Street, they had to finally settle for leasing a drab house on the aptly named Ash Street (adjacent to the local railroad tracks), he was always able to lose himself in the many books that fed his fervid inner hunger for drama, heroics, and intoxicating stories.

Other intoxicants were absorbed as Jones’s cigarette smoking and drinking patterns took hold. He was a heavy smoker and two-fisted boozer most of his life.

Girlfriends of any lasting significance were not part of Jones’s adolescence in Robinson, although his admittedly colossal sexual appetite kicked in at that time. In certain stories featuring his narrative alter ego, John Slade, the theme of chronic sexual frustration is both overt and covert. Once again, his mother was his nemesis. Ada’s religiosity was merely one reason why she was incapable of being Jones’s ally.

When she caught Jones masturbating on one occasion, she ranted about his sinful ways and warned that if he continued, he’d acquire a black hand. She caught him again, and shortly thereafter used shoe polish to paint his hand black in his sleep. In every way she seemed to be overwhelmed by the world at large all around her.

By the time his high school years were almost behind him, Jones’s view of his mother was anything but affirmative. As his father once tried to converse with Ada about some issue of substance, Jones recalled that her only concern was “flipping through pages of a magazine with a placid bored air.”

Her readings in Christian Science did not enliven her or manage to uplift her. She seemed to her second son to have resigned herself to being one who “drinks coffee and smokes and just sits around,” usually saying “Nothing!” when asked what was on her mind. The fiscal insecurity of the family scarcely improved in the 1930s, and Ada’s reaction to their chronic financial stress was to yield to her own ennui; she behaved as though numb.

Jones believed she had nothing whatsoever to give to the two children still at home with her. Ada was, he later growled, “totally selfish, totally self-centered, and totally whining and full of self-pity.” He once wrote with blistering disdain: “She was basically stupid in the very lowest sense of the word. Whether she had any intelligence to begin with and later lost it or let it atrophy, I don’t know. But she certainly showed no intelligence or sensitivity or sympathy toward Mary Ann and me, not from the first moment I can remember her.” As the father of two children later in his life, Jones parented in ways that were the polar opposite of Ada.

* * *

His 1939 senior yearbook comically expressed surprise that “Jim Jones” made it to graduation at all. They humorously assumed he had no future. Then, as if his high school years required a slapstick Hollywood ending, there occurred on the night of Jones’s graduation an accident symbolizing his hard luck. He volunteered to solve a wiring problem in the skylight area, way high up above the auditorium seats, which were slowly filling up with family and friends gathering that night in June 1939, for Robinson High School’s commencement. The Class of ‘39 was the last graduating class prior to the outbreak of war in Europe the following September.

It was the end of an era. And Jones crashed through the skylight and landed thirty feet below, smashing onto a row of metal folding chairs. No bones were shattered, though he was seriously banged up. He had to borrow a crutch in order to walk through the ceremony.

After graduation, Jones went on the road in his own maverick way. He visited older brother Jeff in Findlay, Ohio, where Jeff had a job with the Ohio Oil Company; briefly Jones worked in construction by day, while at night he and Jeff hashed out the possibility of writing a novel together. Jones then hitchhiked his way to Canada, thumbing for rides and hopping freight cars and bumming along like a Steinbeck character. When his effort to enlist in Canada’s military failed, he went home.

He was still only 17. Less than a week after he turned 18 on November 6, 1939, he enlisted in the United States Army, in the twilight time of what was then still called the Regular Army. The Selective Service System would not begin drafting American civilians until 1940. Jones didn’t enlist because he had a military vocation.

There was no family money to pay for university studies, and his sub-par grades in high school were on the record. Scholarships? Not a chance. But enlisting ensured that he’d be sustained inside an organization that would feed him, clothe him, and by and large take care of him. Enlisting made practical sense. Completely.

He couldn’t have known this yet, but by joining the peacetime Army on November 10, 1939, James Jones crossed a threshold that ensured his destiny as an artist.

He then left home, never to see his parents again.

2

YOU’RE IN THE ARMY NOW!

Dad gave me three bucks when I left Robinson.

∼ James Jones,

(written to his brother Jeff)

After James Jones left home by stepping aboard the Illinois Central railroad train in Robinson, shortly after his enlistment, he wrote to his brother Jeff, describing their parents as “receding before [his] grasp like a mist.” Ramon and Ada Jones had escorted their younger son to the local train depot, to offer their farewell.

“Maybe I’ll never see them again,” Jones added. But having “watched Mother and Dad grow smaller” as the Illinois Central commenced its journey to Chanute Field in Rantoul, Illinois, Jones held his emotions in check and “went back into the train and sat in on a Blackjack game.”

If another soldier had a deck of cards as his talisman, Jones had dice. In the first days and weeks of his Army experience, exhibiting his flair for self-reliance as well as for making new acquaintances when he truly had to, Jones used his skills at shooting craps to guarantee he’d not be wholly dependent on the Army for every little thing. This savvy aspect of young Jones’s persona is crucial.

Ramon Jones’s last offering to his soldier-to-be son was three single dollar bills. If Ramon could have spared more, he would have. In 1939, newspapers cost pennies and an adult ticket to the movies was a dime. Three dollars was not a gross pittance. But it was a pittance.

Nonetheless, Jones resolved two issues simultaneously—one was his reluctance to mingle with others; and the other was his resistance to the idea of being fiscally up against it. Doubtless his economically strained home life for so many years had established in him the conviction that no matter what, he should not allow himself to be without money. He bluntly admitted in a letter to Jeff: “If I didn’t have my dice, I don’t know what I’d do.”

Quickly, Jones got to work. He entered that Blackjack game with the three bucks he’d received from his father as a parting gift. By the time the recruits arrived one hundred miles north of Robinson at Chanute Field in Rantoul, his three bucks had become seven dollars. He broke the ice with his new peers by playing cards or rolling the dice. To Jeff, he wrote: “After four days at Chanute Field, I left for New York with $18, not counting what I’d spent, which was quite a bit. Since then my bankroll has never been less than $6 and as high as $27. With that money I haven’t needed to draw any canteen checks, so my pay will be that much higher. Also, I can buy my meals at the Post Restaurant, when the food is too rotten to stomach.”

In those first four days at Chanute Field, Jones and the other recruits were put through their paces as each man took the required Oath of Allegiance before receiving physical exams and mental tests; followed by the allocation of basic supplies (spare clothes, in addition to a regulation uniform; a knapsack and a mess kit); and of course the all-important mode of identification and information gruffly referred to as “dog tags”: on which each GI’s serial number, blood type, name, and religion were stamped. Debarking for Fort Slocum, New York, he was now GI # 6915544.

* * *

When he arrived at Fort Slocum on November 24, 1939, Jones had yet to be assigned to a regiment. Before he finally received such orders, his time was spent in the company of other unassigned recruits performing an endless array of tedious, laborious chores. The men were ordered to do everything from standard kitchen police duties to hauling garbage; they spent hours picking up scraps of debris or other windblown items found on the landscape. Jones mentioned in a letter to Jeff that he was “working in the Post Exchange heaving beer kegs and cases of pop. I get all the stuff I want to eat while I’m working. Also, it ought to make a man of me.”

The preoccupation with food was hardly incidental. Jones’s domestic background in Robinson may have been a story of upscale comforts reduced to lower-middle-class limitations, but he had still known much comfort and abundance compared to what the Army considered acceptable. On Thanksgiving Day 1939, Jones’s breakfast consisted of one tiny box (a manufacturer’s sample) of cereal, plus a mere half-pint of milk, along with a butter pat (limited to one per man). The main dish was a piece of toast that was slathered in leftovers from the prior night’s dinner. Between the toast (which Jones remembered as “rubbery”) and the slop ladled upon it, he noted that “the stomach-churning dish [is] rather aptly described by the soldier’s word for it: shit on a shingle.”

All the more reason his dice were of paramount importance. Wherever he went in those early Army days, Jones’s ability to hustle with his dice allowed him to care for himself when possible. This applied to more than nutritional matters. In terms of his physical well-being, the money he acquired through playing craps or Blackjack made certain outings possible. In a sarcastic update to his brother Jeff, he wrote: “I can engage in the sports at the Y.M.C.A. building where in spite of their undoubted self-sacrifice for the soldier’s soul, one has to pay to do anything.”

Jones soon spent a week in the base hospital at Fort Slocum. He had already noticed, back at Chanute Field in Rantoul, a burning discharge when he urinated. But he waited until he was long gone from Illinois before reporting such a personal problem to his superiors. Then he spent several days and nights in the company of soldiers being treated for gonorrhea, and his prodigious embarrassment and shame at being in their company lent him some of the essential narrative details that he outlined to his brother Jeff (who also yearned to write) for their projected, never-to-be-written Studs Lonigan-type novel.

Jones admitted to his Army doctors that he had engaged in sexual intercourse approximately five weeks earlier, before leaving Robinson for Rantoul’s Chanute Field. It’s possible that he had paid a visit to one of the well-known and affordable brothels in Terre Haute, Indiana. Only 40 miles away from Robinson, Terre Haute had a red-light district allowing for saloons and bordellos and small-time gambling in what was commonly referred to as a “wide-open town.” It’s likely that Jones’s trouble derived from a brothel; not from a local Robinson girl.

Much to his own relief, he reported to Jeff: “They took a microscopic test of the discharge and my urine. They couldn’t find any gonorrhea germs, but as the symptoms were the same, I was put under observation. While under observation I had a chance to observe the men who had the ‘clap’ as it is called in the army.”

Those days and nights in close quarters with the seemingly amoral, rough-hewn men who “stand around a long sink and treat themselves with solutions” branded Jones’s self-esteem with a pulverizing, acidic impact: “I was so humiliated and ashamed at the aspect of being in the ward with those guys.” Fortunately, his symptoms cleared up and he was quickly returned to Fort Slocum’s routines. The one positive aspect of his quarantine was winning again at Blackjack. Jones had entered the base hospital with twelve dollars, but he left it with twenty-three.

Apprehending the class warfare that percolated throughout the Army’s realm, Jones noted that something as random as an afternoon out at the movies was, in effect, a further reminder of the caste system that now placed him at the bottom.

The only time Jones was in the same domain as girls or women while he was at Fort Slocum was when he went to see a movie, and (he explained to Jeff) the rules were rigid: “There the officers’ children, who are the only girls on the island, sit in the balcony. We common herd sit in the ‘pit’ as the rabble did in Shakespeare’s day also.” Author John Gregory Dunne later noted in his memoir Harp: “Therein lies the subversive brilliance of From Here to Eternity. James Jones clearly understood that an army is predicated on class hatred; patriotism is only a convenient piety.”

Those initiatory weeks at Fort Slocum ended after less than a single month. On December 18, 1939, Jones and hundreds of other soldiers shipped out on the Army transport ship U. S. GRANT, slowly destined for active duty at Hickam Field, close to Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

Two weeks later, after sailing via the Panama Canal and docking briefly in California, an Army band greeted the arriving troops with Sousa marches; and the band was complemented by dancing “hula girls,” swaying like Hawaiian goddesses. The new arrivals were presented with traditional Hawaiian “leis” by the dancers.

Whatever pleasure Jones took in the sight of the bronze-skinned, bare-armed, hip swiveling hula girls was short-lived. His time in the ensuing weeks and months was given over to the daily drills, hikes, marches, and the constant tasks with which the Army structured recruits’ daily lives. From reveille to taps, Jones and his fellow soldiers rarely had relaxation time to enjoy the extraordinarily salubrious weather; although Jones noticed it, after enduring a lifetime of Illinois winters.

However, the comfortable delight provided by the daily sunshine and ocean-swept breezes of Hawaii were more than offset by the hardheaded, shrill-voiced, ass-kicking hourly commands of the sergeants who became at this time the masters of Jones’s universe. Although he did enjoy the percussive rhythms and the precision required to execute precisely the intricate patterns of close-order drill, there was little else about Jones’s continued training that appealed to him. Ironically, the experience tapped into his sense of being a cut above many of those in his midst. By possessing a high school diploma, Jones was doubtless at the top of the list, regarding education attained, amid hard-luck Regular Army recruits.

But it was not necessarily his peers who caused his internal sense of frustrated anger. It was the men giving the orders—they were the bane of his existence. In a note sent to his brother, an astute medley of insights was spelled out by Jones:

“I,” he explained to Jeff, “who am better bred than any of these moronic sergeants, am ordered around by them as if I were a robot, constructed to do their bidding. But I can see their point of view. Nine out of every ten men in this army have no more brains than a three year old. The only way they can learn the manual and the drill commands is by constant repetitions. It is pounded into their skulls until it is enveloped by the subconscious mind. The tenth man cannot be excepted. He must be treated the same as the others, even if in time he becomes like them.”

There was little danger of Jones becoming dull of mind or in any way dimwitted.

In the middle of 1940, his innate gift as a loner impelled him to find his way to the base library. Considering how his youth was anchored (to some degree) by the abundant stacks and the serene privacy of the Carnegie Library in Robinson, it’s no surprise that he frequently visited the Post Library facility available at Hickam Field.

Years later, when he warranted an entry in TwentiethCentury Authors, Jones wrote an autobiographical note summing up how the U. S. Army’s library transformed his life: “I stumbled upon the works of Thomas Wolfe, and his home life seemed so similar to my own, his feelings about himself so similar to mine about myself, that I realized I had been a writer all my life without knowing it or having written.”

The timing of Jones’s discovery of the works of Thomas Wolfe was serendipitous. If his earlier visions of authoring a book (in league with his brother Jeff) had been serious, but not serious enough to compel him to identify himself as “a writer,” then the life-enhancing experience of reading books by Wolfe (who at that time was a larger-than-life figure in contemporary American letters) was a turning point. After he spent untold numbers of hours in mid-1940 reading everything then published by Thomas Wolfe, the reluctant soldier who now envisioned a life as a writer began composing poetry, writing short stories, and drafting articles. Despite each effort being rejected by the editors and publications to whom they were sent, Jones did not stop. He persisted. Much as Wolfe had when he labored in obscurity throughout the 1920s, writing alone, living on hope; all of which Wolfe chronicled in his novels.

* * *

In 1940, the year in which he would turn 19, Jones found that his inner life of emotions, grief, and self-awareness was excavated with powerful force by the experience of reading Wolfe’s pages. The author had died in 1938, due to a brain tumor that had been undetected too long. When he died, two mammoth novels about a young male hero named Eugene Gant (Look Homeward,Angel and Of Time and the River) were immensely popular. Shortly after his death in 1938, two more prodigious novels were published, having been pieced together (from thousands of handwritten, unnumbered, unlined pages) and edited to capitalize on his now growing legend: The Web and the Rock and You Can’t GoHome Again (tracing anew the lifelong quest of a young male American from the South: this time dubbed George Webber) added to Wolfe’s aura.

Because of the exceedingly in-depth scenes of family tumult and dramatic conflict involving a younger son and his unhappy, forever-distressed, overwhelmed mother and her inability to find any peace or calm within the family’s realm, Jones could not help but read in Wolfe’s novels what seemed like a recapitulation of the Jones saga.

If Wolfe’s family-centered miseries and boyhood memories provided the substance for the bulk of Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and theRiver (which track Eugene Gant’s growth from the cradle to college), then the final two novels (published posthumously) lured Jones out of the past and perhaps straight into his still unknown future.

Later in The Web and the Rock and most poignantly in You Can’t Go Home Again