10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

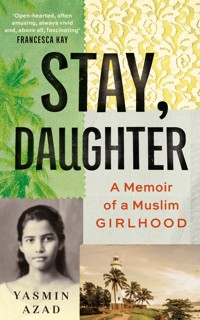

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

We did not stay in our houses. Not in the way our grandmothers had, or our mothers. We went out a little more and veiled ourselves a little less. Some of us longed for more learning and dreamed about leaving home to get it. The elders shook their heads and cautioned: too much education could ruin a girl's future. To be a Muslim girl in the Sri Lanka of the 50s and 60s was to have to stay inside once you hit puberty; where even a glimpse of flesh was forbidden; and where things were done the way they'd always been done. But Yasmin Azad's family is full of love, humour and larger-than-life characters, despite the strictures half of them were under. And almost despite himself, Yasmin's father allows her an education – an education that would open the whole world to her, even as it risked closing her off from those she was closest to. An extraordinary portrait of a time and a community in the midst of profound change, Stay, Daughter vividly evokes a now-vanished world, but its central clash – that of tradition and modernity – is one that will always be with us.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

For my beloved sonsKalid, Siraj and Jehan.And for my nephews and niecesRashid, Ayesha, Naima, Laila and AmalWith much affection

Contents

CharactersGlossaryPrologue123456789101112131415161718192021EpilogueNote to the ReaderAbout the AuthorCharacters

Asiyatha my father’s cousin, who knew the history of his family.

Fathuma Aunty my mother’s cousin, one of the first Muslim girls to pass the eighth grade Junior Cambridge examination.

Kadija Marmee a close female relative who regularly visited our home.

Kaneema Marmee my mother’s first cousin (Thalha Cassim’s eldest daughter).

Mackiya Thatha my mother’s second cousin; she is notable as a rare older Muslim female who never married.

Penny my childhood friend in the Galle Fort. A Christian of Dutch Burgher descent. I addressed her mother and father as Aunty June and Uncle Quintus.

Rameesa Marmee the daughter of one of my father’s half-brothers, particularly close to me.

Rohani Cassim my great-grandfather (mother’s father’s father), notable for his radical decision to send his daughters to school.

Shinnamatha one of several poor women who made a living in the Galle Fort through domestic service.

Thalha Cassim my mother’s aunt, eldest daughter of Rohani Cassim and the first Muslim girl in Galle to go to school.

Zain Marma one of my mother’s maternal uncles to whom she was particularly close.

Zain Marmee Zain Marma’s wife, whom we affectionately called by her husband’s name.

Zubeida Marmee a close female relative who regularly visited our home.

Glossary

The words for family members are often used as an honorific after a person’s given name. For instance, ‘Nana’ (elder brother) can be attached to the name of any older male. Majeed Nana, the travelling salesman, is no relation to the narrator.

Hadith a saying of the prophet Muhammad. Different scholars, at different times, compiled the sayings decades after Muhammed had died. So “Hadith, Abu Dawood” indicates that this is a saying from Abu Dawood’s collection.

kafir infidel or one who does not believe in Islam

komaru an unmarried female past puberty

mahath-thaya honorific meaning ‘sir’ that follows a man’s given name

marma uncle

marmee aunt

Marshazi a Tamil word meaning ‘a different kind’, used to refer to people who are not Muslim

marumahal niece or daughter-in-law

nana elder brother

Parangi a person of European descent

periumma a mother’s elder sister or an older female first cousin

shachi a mother’s younger sister, or a younger female first cousin

thambi younger brother

thatha elder sister

ulema Islamic religious scholar

umma mother

wappah father

wappumma grandmother (father’s mother)

Prologue

And stay in your houses, and do not display yourselves.

The Quran, 33:33

We did not stay in our houses. Not in the way our grandmothers had, or our mothers. We went out a little more and veiled ourselves a little less.

Casting off the heavy black cloaks that had once shrouded females from head to toe, we covered ourselves, instead, in flimsy veils. Draped lightly around our heads, the silks and voiles fell casually from our shoulders, and in the minutes it took for us to get from front door to car, a stranger walking on the road could make out the features of our young faces, the curves of slender waists and hips. Sometimes such a stranger fixed his eyes on us. And sometimes we looked back. Mothers drew our veils closer and hurried us away; you shouldn’t allow yourselves to be seen like that, they told us.

Like girls fromnon-believing (kafir) families, we went to school, and stayed there even after we had become ‘big’. And still more like them, but so unlike our mothers, some of us longed for more learning and dreamed about leaving home to get it. The elders shook their heads and cautioned: too much education could ruin a girl’s future.

The world outside was pressing in on us and when I turned twelve, Wappah, my father, thought it time to tell me a story. Many years ago, my father reported, when our country, the island of Ceylon, was still a British colony, an Englishman – perhaps the Governor himself – had invited a Muslim statesman to dinner. ‘Bring your wife too,’ the important official said. ‘I have never met her.’

‘Aah,’ came the reply. ‘That is not possible. She is in purdah and cannot be seen by men outside the family. But,’ the Muslim man continued, as he pulled out a rose from a nearby vase, ‘look at this. It would be just like looking at her.’

If we felt the stirring of wishes unknown to our mothers and grandmothers, we didn’t tell them. They would have been shocked, like Wappah, who had only known women like flowers.

1

Men are the protectors and maintainers of women.

The Quran, 4:34

Not three years after she had been a bride, Wappumma, my father’s mother, became a widow.

‘She went into shock when they brought the news to her,’ Aunt Asiyatha said. ‘Rolled on the floor and wailed. What was she going to do? Your grandfather had died in Bombay on the ship bringing him back from Mecca. “Who will guard us now, who will guard us?” your wappumma kept asking. She was six months pregnant too. Lost the baby.’

Aunt Asiyatha was my father’s cousin – the adopted daughter of his mother’s only brother. When, as a girl, I accompanied Wappah to his childhood home in the village of Shollai where his sister still lived, she was often there. Patting down a straw mat spread on the floor, my aunt would say, ‘Come sit here; I have some things to tell you.’ I would sidle right up. As far back as I can recall, I latched on to anyone who would tell me a story.

Aunt Asiyatha spat out a stream of dark red betel juice and continued. ‘What was your wappumma going to do? Your father was a toddler, and his sister only a little older than that. Who was going to look after them?’

‘Didn’t Grandfather have money?’ I asked.

‘Yes, but he had all those children from his first marriage. He couldn’t leave everything to your grandmother. Soon, the money was used up, then the jewellery was sold, and all the plates and most of the furniture, and in a few years there was nothing left.’

‘Didn’t they own land?’

‘All that came to nothing. The paddy field in Weeraketiya, she used to get a bag of rice once or twice a year, but the rest of the properties, nobody knows what happened to them.’

‘What do you mean, no one knows what happened to them?’

Aunt Asiyatha leaned over and lowered her voice. ‘Don’t tell your father I told you – you know how he is when anyone speaks badly of his relations – but they say a man, one of our relatives, he brought your wappumma all kinds of papers, got her to rub ink on her thumb and put it down, and one by one the properties were gone. We think they were sold off.’

‘But what was written on those papers?’

‘Allah, child, how would your grandmother have known?’

My father’s mother could not read or write. She couldn’t tell time or make out a calendar. She needed help counting money.

‘When were you born, Wappumma?’ I once asked her.

‘When was I born? My mother told me it was during Uncle Omar’s wedding. Cousin Fathuma was just learning the aleph, bey, thay of the Quran, and her little brother had begun to eat solid food. That’s when I was born.’

‘No, which year. How old are you?’

Wappumma knitted her brow and shook her head.

My grandmother’s life kept rhythm with the moon; she kept track of its waxing and waning. Every four weeks or so, when it seemed about time, she stepped out into the garden and searched the night sky. If she spotted what she was looking for – the faintest of crescents glowing in the dark – she hurried to announce that a new month had begun. Her days began when the stars came out; she said her Friday prayers on Thursday night.

Though she fathomed little about things outside her home, Wappumma was convinced she understood the workings of the world. Someone envious had cast the spell that had taken away her husband and comfortable life. How else could it all have ended like that? But she protected her family now. She hung amulets on her son and daughter – sachets of magical charms tied with thick black string and secured around arms and necks and waists. They warded off the evil eye and the evil tongue and the many other evil vapours the whole village knew were waiting to enter the unsuspecting orifices of children. She said special prayers at night time, too, to keep away the demonjinns.

Once, she found a pumpkin in her backyard that no one could account for. Who had thrown it there? Maybe that same evil person who had cast the first spell. Had she been a fool and cut the fruit open, streams of blood would have come pouring out and put a hex on everything in the house. She yelled out a curse and threw the jinxed fruit over the fence. She was too clever for her enemies.

When I was about eight, Wappumma placed an amulet around me too, but my mother took it off. Umma said that it was mostly people in the villages who wore such things. She didn’t add that people in a town like her home of the Galle Fort, where we now lived, never descended to such behaviour, but I sensed that was what she meant. I was happy to take it off.

When her husband died, somewhere around 1910, the colonial officials representing His Majesty in the district of Galle requested that my grandmother submit wills, affidavits and properly notarised deeds. The Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages, of whose existence she had barely been aware, demanded to know the exact dates of events. Wappumma looked to a man in her family, someone who knew the ways of the white people, to stand in her stead at the courts and registries. Perhaps it was he who had brought those documents and said, ‘Put your thumbprint here.’

Aunt Asiyatha tucked a fresh wad of betel leaves into her mouth and fixed her eyes on my father who was sprawled on a recliner on the other side of the back verandah, chomping on his cigar.

‘He it was who guarded them. Your grandmother, she always said, “My little Abdul Rahuman, after he began to work, we never stretched out our hands to anyone.”’

My father’s sister, whom I called Marmee (Aunt), brought out cups of cardamom-flavoured tea and joined the conversation. ‘Thambi was so small when he went to work, half a sarong would cover him from waist to ankle. Our umma would cut one in two and hem the edges. That way he had one piece to wear while the other was in the wash.’

Wappah pitched his voice across the room, as his ears had picked up the familiar term for little brother, thambi. ‘I always woke at dawn. As soon as the muezzin at the mosque called out the morning prayer I jumped up from my mat.’

‘Nice jumping up from the mat!’ Marmee laughed. ‘I shook his shoulders and shouted into his ears and splashed water on his face, but he just pulled his sarong over his head and rolled over. Then Umma put her head into the room and yelled. “Only a boy visited by Satanwould sleep until the sun shone on his behind!” That’s when he got up.’

‘As though the sun could have shone on my behind or anywhere else in that dark corner of the floor where I slept!’ Wappah scoffed. ‘But I didn’t say that to my mother. Would have got a good slap on my face if I had.’

‘That’s right.’ Marmee lowered her voice. ‘In those days, he was not a periyal, a boss. He had to listen to us. We told him what to eat and when to go to sleep and made him take his baths. And that… Subhanallah!’ My aunt shook her head and raised her eyes and hands upwards.

Wappah, Marmee said, would run all over the house and garden to escape a bath at the backyard well. He crept under coconut fronds, squeezed his scrawny frame behind the outhouse, climbed into empty gunnysacks. His mother always found him. Her hand curled tight around his bony wrist, she would drag him across the yard, over drying jak leaves, goat droppings and chicken feathers and set him down on a slimy patch of ground by the dugout well where his sister waited – a bucket of water drawn and ready.

When the first chilly cascade landed on his head, he sputtered and hopped from foot to foot. His teeth chattered. He snorted water out of his nose and shook it out of his ears. Before he could catch his breath, another torrent of cold water hit his shoulders. Then another and another.

‘Scrub all the dirt out, or he will get sores again!’ Wappumma would shout from across the yard where she squatted over an open hearth, making breakfast.

Marmee would wedge a sliver of yellow soap into a piece of coconut husk and scrub: neck and back, arms and shoulders, down the legs and the spaces between the toes. When the next bucket of water landed, it fell on skin scraped red. Her brother screamed.

‘When Thambi got his first job,’ Marmee smiled, ‘he started to take good baths on his own. He knew he had to look good to work in a place like the Galle Fort.’

A relative who knew of Wappumma’s descent into poverty had secured for her young son a job as apprentice to a jeweller in the Galle Fort, a fortress in the south-west corner of Ceylon. This had been the military stronghold of European colonisers for many centuries. Built by the Portuguese in 1588, some decades later it was wrested away by an invading Dutch army. Finally, in 1796, it came into the possession of the British, the last of the Westerners to rule the island. By the early twentieth century, when my father was a boy, the Fort was no longer an army garrison. It had become the administrative and commercial capital of the southern province. A thriving citadel with hotels, warehouses, shops, schools and churches, it was also home to civilians, several of whom – and this was of utmost importance to Wappah and everyone in his village – were some of the most prestigious Muslims in the country.

When her brother set off in the morning, Marmee stood at the front window to watch him leave. He was eleven or twelve (no one in the village knew exactly when they were born) when he first began to work, and she, being about two years older, was by this time a ‘big girl’ who had been brought inside. To keep herself unseen by strange men, she did not set foot outside her home during the day. As a komaru – a female past puberty but not yet married – the rules of seclusion were far stricter for her than even for her widowed mother.

Pressed against the wall and leaning against the wooden frame of a little window, Marmee got as good a view as she could of the road beyond. A little while ago, her mother had made breakfast. Squatted over the open hearth, she had swirled a batter of flour and coconut milk in a sizzling pan, and made hot, crisp rice wafers. The smells wafted in and mingled with the odour of damp walls, dirt floors and goat droppings that always hung in the air of the little house.

Outside, the dew was wet on the grass and the only people to be seen were the men in white tunics and caps who were returning from dawn prayers at the mosque. Marmee’s eyes followed her young brother as he walked along a footpath that led away from clusters of small houses built with bamboo and clay. She saw him swipe a juicy guavafrom a neighbour’s garden and tuck it into the knot of his sarong. The ground was cool to the soles of his bare feet but soon the sun would rise, and before he reached the Fort, more than two miles away, beads of sweat would glisten on his forehead. A few feet ahead, beyond a grove of coconut trees, was Talapitiya Road, the main highway that cut through the village of Shollai. There, he took an abrupt turn and vanished from sight.

‘I waited all day for him to return,’ Marmee said. ‘When it was time to light the oil lamp at dusk, I went back to the front window and looked out.’

Leaning in against the wall again, and peering out through the wooden bars, she caught sight of the coconut palms that threw long shadows on the grass. The same men and boys in white tunics and caps who had been out in the morning were now on their way to the mosque for evening Maghreb prayers. They walked by the house without making out any part of her, not at all suspecting that a pair of girlish eyes was gazing out into the world.

Her brother came into view as he turned off the main road – a small figure lugging a basket of fish and vegetables, veering from side to side to avoid the piles of cow dung that dotted the field. When he approached the front steps Marmee called out to her mother, and Wappumma hurried to take down the bar that had been laid across the front door. It had been there since her son left in the morning to shut out anyone or anything that could intrude on the modesty of the widow and her daughter.

‘Don’t let any outsiders in before you have given us time to hide,’ Wappumma always told her son as he stepped inside. Now that he was home, neighbourhood boys and male cousins several times removed might walk into the house. He didn’t need the warning. Early on, he had acquired the trait that was to last a lifetime – the fierce protection of female honour. Always acutely aware of the presence, in his home, of the non-mahram – theunpermitted male – he allowed no man in before he had shouted out a warning and heard the patter of female feet hurrying away.

The first sign of such a man approaching, and Marmee fled. She didn’t linger a second longer than she should have. Or so she told me. She appeared to be one of those girls, so numerous in those days, who if their elders drew a line on the ground and said, Don’t put your foot beyond this, not even one little bit, they never did. I didn’t ask Marmee whether she was ever curious about which man or boy was coming into the house. The question would have flustered her. It wasn’t something she allowed herself to think about: that she could choose to look or not. Her life was what it was supposed to be, nothing more or less. This was the key to the unquestioning obedience always held up for those of us who were showing signs of being less than perfectly docile. Besides, one of the lines drawn inside my own head, which I did not easily cross, was the one that said, Don’t ask unnecessary questions.

No sooner had he stepped inside than Marmee eagerly asked her brother what he might have seen in the Galle Fort that day. He brought reports of buildings three and four times as tall as their house, verandahs enclosed with rows of glass windows, and gates of polished brass you could mistake for gold. She tried to imagine what a motorcar looked like, marvelled that white ladies walked all on their own in broad daylight, and that children were taken around in wheeled carriages. The day she heard about water that had turned into cold blocks of stone covered in sawdust, sold by a man who pushed a cart, she wondered whether her brother made things up.

Marmee was most impatient to know about the happenings in the homes of the wealthy shangakara Muslims in the Galle Fort. To be told about their large houses with ornate gables, tiled roofs, spacious courtyards and name boards with English lettering: ocean view, eglington, jasmine cottage, hayley; the ebony divans and elaborately carved tables set up in the front halls; the tall ceramic vases and dwarf palms along the inner courtyards. And how intricately carved and beautiful were the wooden lattice screens that sealed off, without exception, the women’s quarters.

Her brother described what he saw as he walked by the Dutch double doors that opened out onto wide verandahs. What lay within he didn’t know. He never stepped inside any of those stately homes. In those early days, Kuhaffa Hadjiar’s jewellery shop on Leyn Baan Street had the only smooth floor in the Galle Fort that took the imprint of his dusty feet.

Before Marmee was done with her questions, her mother waved her aside. The widow, too, had waited all day for her son to come home.

‘A jackfruit fell down in the front garden. Pick it up before someone else does… Walk to Cousin Zubeida’s house and tell her I’ll come by to see her after dark… I’ve been waiting to drink something. Can you pluck a king coconut for me?’

Wappah was happy to oblige – he didn’t want his mother to go outside her home more than absolutely necessary. They may have been poor, but he wasn’t going to allow people to say the females in his family roamed the village like kafir women.

His presence at home was valued most, at least by Marmee, when the roving salesman, Majeed Nana, came to the village. The itinerant trader carried on his head a huge cloth bundle packed tight with textiles and fancy goods, and his appearance always thrilled the maidens of Shollai who never set foot in a shop themselves.

A few weeks before the great festival of Ramadan, wives, daughters, sisters and aunts would divulge their preferences to the men in the families who did the shopping for them.

Some men ignored these declared choices and bought what they thought would look good on their female relatives; others, returning home with arms full of packages, learned to their befuddlement that taffeta was not the same as satin, and that silk came in various grades and textures, some more desirable than others. A few particularly sharp fathers and brothers did know how to choose ‘a saree with thread work along the edges but nothing on the front border and no sequins unless they are the kind that wouldn’t come off if a small child was to tug on the fabric’.

Lately, some fashionable Fort ladies had begun to ask that they be taken to the entrance of textile storesin the Galle bazaar. Seated safely inside their curtained buggy carts, they chose from bolts of fabric that were brought to them. Marmee found it hard to believe that women could be so forward.

She gave no instructions, either, to her brother, or so she said. And whatever Wappah brought her was alright, she also said. Yet she counted the days till it was time for Majeed Nana to visit the village.

On one such day, when she was fifteen or so, Marmee heard a loud voice.

Sarongs! Saris! Cloth!

Sarongs! Saris! Cloth!

She searched for her brother. Where was he? Had he stepped out into the backyard, or gone to look for their roaming goats? Was he in the outhouse? She had no time to lose. If no voice stopped him – and only a male voice could do that – the trader would walk right by their house.

Wappah had heard Majeed Nana too and came running. When he called out, the cloth trader stopped and turned, then with slow steps walked up to the small house. At the front door, he propped a wooden yardstick under the bundle on his head, shifted it to his shoulder and carefully brought it to the ground.

‘Salaam alaikum, salaam alaikum,’ Majeed Nana said aloud, as he wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. He pitched his greeting into the air as though he was speaking to no one in particular. But he knew full well that watching his every move through a crack in the doorway, holding their breath until he untied his package, were the women of the household, the older, married females holding the door ajar, and the komarus standing behind, peering over their shoulders.

‘Shiny satin… Manipuri sarees… Chintz… India muslin… Java sarongs…’

Majeed Nana described his merchandise aloud as he laid his wares one by one on a white cloth. ‘Why,’ he exclaimed, in a voice that carried into the house, ‘this is what you get in all the fancy stores. If truth be told,’ he pitched his voice a little higher, ‘this is what the Fort ladies like.’

The cottons came first: the cambric and flowered chintzes women used for everyday wear, the striped Java sarongs worn by men. Next, lace, both broad and narrow, for trimming blouses and underskirts. And last of all, the sarees: delicate voiles, Manipurisilks with intricate cord work, georgettes embroidered in every colour of the rainbow. When Majeed Nana wiped his hands on his sarong and unfolded the yards of an embossed chiffon,Marmee gave a little gasp.

She had no place to wear such a saree. Besides, they could not afford it. But Wappah brought it in for her to see.

‘Take your time, take your time,’ the trader said, speaking into the air once again in an unhurried manner. He was well used to sitting on his haunches on some front verandah, while men and boys carried his merchandise in and out. Women rubbed their cheeks against soft silks and murmured. They draped liquid folds over their shoulders, ran their fingers over delicate embroidery, held shiny fabrics up to the sun and chose what to keep and what to give back.

After the textiles had been displayed, Majeed Nana took up the tin box that had been at the very top of his bundle. Inside, in a tray divided into compartments, were coral beads, perfumed soaps, and talcum powder. He set all that aside and reached for the container at the very bottom. Marmee tightened her hold on her mother’s arm.

Nestling in folds of white voile were dozens of glass bangles: red, blue, green, yellow, even gold; some multicoloured, some striped diagonally over the narrow bands, others with shiny specks inside the glass. They glinted in the light. With just two bangles on her wrist, a girl could make a delicate, tinkling sound.

Marmee turned to her mother.

Wappumma shook her head. ‘The glass will break when you do your housework; and where else could you wear them? Where do you go, child, that anyone would see?’

Marmee bit her lip and said nothing.

But Wappah walked up to Majeed Nana’s box and picked up a pair of bangles. He said if it made his sister happy, he would buy them for her.

The next morning, after her son had left the house, the widowed mother placed the crossbar against the front door and closed it.

2

Let not the believers take the disbelievers as friends.

The Quran, 3:28

Because it was the custom among our people that when a man married he moved into his wife’s home, our family lived in the Galle Fort, where Umma had been born.

After some years as a jeweller’s apprentice, Wappah had struck out on his own. He had become wealthy enough to be considered an eligible bridegroom for a daughter of the prestigious Cassim clan, to whom Umma belonged. Marriages like that took place when a Fort family could find no one among themselves for a girl who was unmarried and growing old. No one ever explained why Umma, whom everyone considered beautiful and elegant, had not been able to marry earlier. I couldn’t really ask, that being another unnecessary question, but I suspect it had something to do with the decline of family fortunes – the decline that often happened to subsequent generations of wealthy families. Where no big dowries could be offered, people who were otherwise keen to be set apart from those who lived in the villages allowed themselves to consider an up-and-coming bachelor from a place like Shollai.

The Galle Fort, this place where I grew up, was like no other. Or so the ulemas, the religious scholars of Islam, must have concluded with great consternation. They insisted the faithful keep away from the kafirs; inside this cramped citadel, no one could keep very much away from anybody else.

Perched on a cliff that jutted out into the sea, the Fort was on a small outcrop of land surrounded on three sides by water. Inside, within an area that was less than a tenth of a square mile, lived hundreds of people. With roofs and gutters touching, and only a common wall in between, their houses jostled against each other. To talk to a neighbour, a person stood in his courtyard and shouted over a wall, or sat on the steps of the front verandah and pitched his voice across.

The back doors opened out to narrow alleyways, giving cover to Muslim women who wanted to visit their relatives without walking the streets. They also opened out to minuscule pieces of land that families used for raising livestock. Here, a neighbour’s goat wandered over to chew on sprigs of jakleaves brought from the countryside, and a neighbour’s ducks waddled in to splash in mud puddles left behind by monsoon rains. The smells from adjoining kitchens mingled and wafted in the breeze and into this mix was added, every day, another odour, when the bucket man from the municipality opened a latched door at the back, and emptied into his handcart the brimming pails that he pulled out from the latrines.

My mother’s youngest uncle, known to us as Zain Marma, insisted that the first Muslim allowed to live inside this citadel was one of our own ancestors. Nearly two centuries ago, his great-great-grandmother, Rahima Umma, a widow with seven daughters (all of them very beautiful, Zain Marma emphasised), had lived in Magalle, a small town a few miles north of the Fort. Some hooligans who knew about the pretty girls began to harass the family and one night the notorious bandit Kitchel, who worked with the fearsome robber Gurubaldi (so Zain Marma’s story went), broke into the house to abduct them. Although the cries of the women brought out the neighbours, and the widow and her daughters were saved, the next morning the terrified mother appealed to the colonial authorities to give her a safe place to live.

At the time there was a Dutch law that restricted Muslims – whom the colonisers called Moors – to their own enclaves in the country, but in 1774 Rahima Umma was allowed to move to the safety of the Fort with its army barracks and impregnable walls.

Not everyone in the Fort was willing to accept that it was someone in Uncle Zain’s family who had been the first to move there – such distinctions were only grudgingly conceded. But when challenged, Uncle Zain whipped out the evidence: Dutch Governor Willem Jacob van de Graaff’s census of 1789 did have an entry for a Moor widow with seven daughters living in the Fort; and the name of the widow was recorded as Rahima Umma.

When this great-grandmother several times removed first settled into a house on Church Cross Street, she lived as a lone Muslim among Christian Burghers – the middle-class traders from Holland whom the Dutch had encouraged to migrate to their Asian colonies. After the British repealed in 1832 the law that restricted the rights of the Moors to live where they wanted, more of them migrated into the Galle Fort. Traders by profession, they appreciated the advantages of living near what was then the country’s principal harbour. Eventually, a large community of Muslims came to live inside this fortress, among the descendants of the white-skinned people who had colonised Ceylon. We called them Parangis, from the Arabic for Frankish crusaders, ferengi.

‘Grandfather Rohani Cassim spent so much time with the Parangis,’ Kaneema Marmee told me, ‘people began to talk.’

Kaneema Marmee was the oldest of a group of relatives who regularly got together to chat over afternoon tea. She was Umma’s first cousin. Nearly every day, they gathered at our house on Lighthouse Street in the Galle Fort to sit in our spacious courtyard and be cooled by gentle sea breezes. The savoury pastries and sweet confections our cook laid out made it even more of a favourite venue.

‘What were they saying about your grandfather?’ I asked Kaneema Marmee. Someone had laid themselves open to almost the very worst thing that could happen to a person – have people talk about them. Someone in my own family, no less. Had this person not cared? I felt a thrilling shudder at the mere thought of such boldness.

‘They complained that he was spending too much time with the Marshazis.’

Marshazi was a term for people who were unlike us: maru in Tamil meaning ‘different’, and shazi meaning ‘type’. The Parangis, who were Christian, naturally fell into that group. They were kafirs from whom, the ulemas warned, we were to stay away.

‘Didn’t other people do that?’ I searched my aunt’s face as she took a bite from a crisp savoury pastry.

‘Not the way he did.’