Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Confident and very readable . . . one of Frances Spalding's achievements in this book is to display Stevie Smith's frailties without destroying her dignity' – Victoria Glendinning, Literary Review 'A careful, informative and worthwhile book' – Hermione Lee, The Observer 'It is a biography of inner life. It is also a hymn to tenebrous suburbia, a book full of English oddness, and a lovely loamish read.' – The Times Stevie Smith had a unique literary voice: her idiosyncratic, wonderfully funny and poignant poems established her as one of the most individual of English modern poets. She claimed her own life was 'precious dull', but Frances Spalding's acclaimed biography reveals a far from conventional woman. While she lived in suburbia with her beloved 'Lion Aunt', Stevie Smith was from the early 1930s a vibrant figure on London's intellectual and literary scene, mixing with artists and writers, among them Olivia Manning, Rosamond Lehmann and George Orwell. She was noted for her wit – often maliciously directed at friends – and occasional public tantrums. Her use of real people in her writing angered many of her friends and brought the threat of libel. Always feeling herself out of step with the world, she was haunted by her father's absence during her childhood and her mother's early death; she longed for love yet was sexually ambivalent. In exploring the intimate relationship between Stevie Smith's life and work, Frances Spalding gives a new insight into a writer who always saw death as a friend, yet was also one of the great celebrators of life, whether commonplace or extraordinary.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 729

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

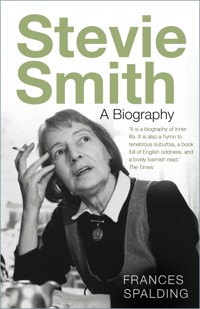

Front cover image © estate of J. S. Lewinski / National Portrait Gallery, London

First published in 1988 by Faber and Faber Limited

This new revised edition first published in 2002 by Sutton Publishing

This paperback edition first published in 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Frances Spalding, 1988, 2002, 2025

The right of Frances Spalding to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 943 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

List of Abbreviations

Introduction to the Revised Edition

1 From Hull to Palmers Green

2 North London Collegiate

3 Bonded Liberty

4 Dear Karl

5 As tiger on padded paw

6Novel on Yellow Paper

7 The Power of Cruelty

8 Wartime Friendships

9 Fits and Splinters

10 Madness and Correctitude

11 Not quite right

12 Fixed on God

13 Frivolous and Vulnerable

14 In Performance

15 Black March

Appendix: Stevie Smith’s Published Works

Notes

Acknowledgements

My thanks go first of all to Stevie Smith’s literary executor, James MacGibbon, for granting my request to write this book. I am further indebted to the following for generous assistance: Mr Walter Allen; Miss Diana Athill; Mr Paul Bailey; Mrs Vera Baird; Mr Jack Berbera; Miss Rosemary Beattie; Mr Mark Bence-Jones; Mrs Peggy Blackburn; Dr Marjorie Boulton; Mr and Mrs John Bradford; Miss Margaret Branch; Mr and Mrs Neville Braybrooke; Miss Maria Browne; Mr and Mrs Michael Browne; Professor Norman Bryson; Mr George Buchanan; Miss Jessie E. Buckfield; Mr Robert Buhler; Mrs Racy Buxton; Mrs Freda Calstern; Mrs Lilian Carpenter; Mrs W. E. A. Chatfield; Mrs Sally Chilver; the late Douglas Cleverdon; Mrs Nest Cleverdon; Mrs Barbara Clutton-Brock; Mr Stephen Coan; Mrs Becky Cocking; Mr Robert Cook; Miss Lettice Cooper; Miss Rosemary Cooper; Mr Nicholas Cottis; Miss Jeni Couzyn; Professor Maurice Cranston; Mrs Eleni Cubitt; Dr James Curley; Mr A. J. Davey; Mr Ian Davie; Mr Michael De-la-Noy; Mr Nigel Dennis; Mrs Doreen Diamant; Miss Kay Dick; Mr Patric Dickinson; Mr John Drummond; the late Donald Everett; Mrs Molly Everett; Miss Kathleen Farrell; Mrs Vicki Feaver; the late Wallace Finkel; Brigadier and Mrs Laurence Fowler; Miss Peggy Fox; Miss Margaret Gardiner; Mr Richard Garnett; Mrs Lucy Gent; Miss Stella Gibbons; Miss Helen Glatz; Miss Deidre Good; Mrs Celia Goodman; Mr John Guest; Mr Michael Hamburger; Mrs Sally Hardy; Sir Rupert Hart-Davis; Mrs Gertrud Häusermann; Mr John Heath-Stubbs; Miss Judith Hemming; Mrs Kitty Hermges; Mr David Heycock; Dr Polly Horvat; Mr Michael Horovitz; Sir Fred Hoyle; Miss Audrey Insch; Revd Gerard Irvine; Mrs Susannah Jacobson; Miss Helen Jessop; Mr Rory Johnston; Mr Leo Kahn; Mr Peter Kiddle; Mr Terence Kilmartin; Professor Ruth Landes; the late Philip Larkin; Miss Marghanita Laski; Mr James Laughlin; Mr and Mrs George Lawrence; Sir John and Lady Lawrence; Miss Rosamond Lehmann; Miss Naomi Lewis; Mr Eddie Linden; Professor William McBrien; Mrs Jean MacGibbon; Miss Cecily Mackworth (La Marquise de Chabannes la Palice); Miss Judith Maravelias-Eckinger; Mr Derwent May; Mr Christopher Middleton; Dr Jonathan Miller; Miss Margaret Miller; Miss E. Margo Miller; Miss Sarah Miller; Mr Adrian Mitchell; Professor Charles Mitchell; Mr David Mitchell; Mr T. H. Mobbs; Mr John Morley; Miss Lin Morris; Lord Moyne; Mrs June Nethercut; Mr Peter Newbolt; Mrs Margaret Newman; Miss Juliet O’Hea; Miss Armide Oppé; Mr Ronald Orr-Ewing; Mrs Olive Pain; Mrs Trekkie Parsons; Mrs Frances Partridge; Mrs Brian Patten; Mrs Kathleen Peacock; Mrs Elizabeth Popley; Mr Anthony Powell; Miss Joan Prideaux; Mrs Eleanor Quass; Miss Margaret K. Ralph; Dr Priaulx Rainier; Mrs Joan Ransom; Miss Helen Rapp; Miss Naomi Replansky; the late Dame Flora Robson; Mr Jeremy Robson; Mr C. H. Rolph; Mrs Joan Rowell; Mr Piers Russell-Cobb; Mr Trevor Russell-Cobb; Mrs Natasha Shokoohy; Mr Norman Shrapnel; Mr Arthur Shrimpton; Mr Bill Shrimpton; Mrs Mary Siepmann; Mrs Nickola Smith; the late R. D. Smith; Miss Phebe Snow; Miss Muriel Spark; Mr Colin Spencer; Professor Ernest Stahl; Mr Quentin Stevenson; Miss Jane Stockwood; the late George W. Stonier; Mr Walter Strachan; Mr Robert Sykes; Mr and Mrs Stefan Themerson; Mr and Mrs Anthony Thwaite; Mr T. E. Utley; Mrs Jane Wailes; Mrs Antoinette Watney; Mrs Susan Watson; Dame Veronica Wedgwood; Mr Christoph Werner; the late Eric W. White; Mr Richard White; Mr Jonathan Williams; Mr David Wright; Mr Ian Whybrow; the Misses Nina and Doreen Woodcock; Mr Francis Wyndham.

I am also indebted to various institutions and their staff, for access to Stevie Smith letters or related material: to Mr Graham Dalling and Palmers Green Library local history collection; to Mrs Anne Piggott and The Times newspaper archives; to Mr Jeff Care and the Observer for access to files and microfiche; to Miss Anne Galloway and the New Statesman archives and to Mrs M. Hancock and the City University for New Statesman correspondence; to Miss Amanda Mares and the BBC Written Archives; to Mr Jonathan Vickers and the National Sound Archive; to the staff of Palmers Green High School; to the former headmistress of North London Collegiate School, Miss Madeleine McLauchlin and to its archivist Robin Townley; to Dr Michael Halls and King’s College, Cambridge; to Mr Michael Bott and Reading University Archives; to Professor G. D. Zimmermann and the University of Neuchâtel; to the university libraries at Birmingham, Dublin, Durham and Hull; to the National Library of Scotland and the National Library of Wales; to Washington University Libraries; Smith College Library, Northampton, Massachusetts; Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; Lilly Library, Indiana University; the State University of New York at Buffalo; to Abbot Leo Smith and the monks at Buckfast Abbey; to Mr Edwin Green, archivist of the Midland Bank Group; to the Public Records Office; the British Library and its newspaper branch at Colindale. I am also indebted to the publishers Jonathan Cape, André Deutsch, The Bodley Head, Longman, New Directions and Alfred Knopf for access to archival material. In addition I would like to express especial gratitude to John Kirby and his excellent staff at the Faculty of Cultural Studies, Sheffield City Polytechnic, and to Mrs Caroline Swinson and her staff in the Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa, for all the help and hospitality they provided during my visit to Tulsa. Their Stevie Smith collection at that time contained her library, manuscripts of her poems and The Holiday, a large collection of drawings and Smith family memorabilia.

I am grateful to the following for permission to quote from copyright material: to Helen Fowler who generously lent me her unpublished memoir on Stevie Smith; to Celia Goodman for extracts from Inez Holden’s unpublished diaries; to Neville Braybrooke and Francis King for an extract from Olivia Manning’s unpublished memoir, ‘Let me tell you, before I forget . . .’; to Neville Braybrooke for an extract from a Barbara Jones letter to Jonathan Williams; to Norman Bryson for an extract from a letter to myself; to Judith Maravelias-Eckinger for letters from her father, Karl Eckinger, to Elfriede Thurner; and to James MacGibbon, Penguin, Virago, Longman and New Directions for extracts from Stevie Smith’s poetry and prose.

Especial thanks go also to my editors at Faber and Faber, Frank Pike and Jane Robertson, to Maureen Daly for typing assistance, and to Sheila Walker, Kathleen Moynahan and Julian Spalding for making this book possible.

List of Illustrations

1 Stevie Smith. Publicity photograph taken by Howard Coster for Novel on Yellow Paper

2 John Speer

3 Charles Ward Smith

4 Madge Spear

5 Ethel Smith

6 ‘Peggy’ Smith, aged three

7 Stevie as Ali Baba

8 Sydney (Basil) Scheckell

9 Ethel Smith, summer 1918

10 Stevie

11 Hester Raven-Hart

12 Molly Smith

13 Karl Eckinger

14 Eric and Katherine Armitage on their wedding day

15 Aunt and Molly

16 Inez Holden

17 Stevie at the home of Horace and Rachel Marshall in Cambridge

18 Kay Dick

19 Kathleen Farrell

20 Mulk Raj Anand

21 Olivia Manning

22 Stevie Smith, 1965

The drawings at the chapter openings are by Stevie Smith.

List of Abbreviations

When a quotation from one of Stevie Smith’s poems is used a reference is given only if neither the title nor first line appear in the text. In the case of the three novels I have chosen to refer, not to the original editions, but to the Virago reprints, currently available.

NYP

Novel on Yellow Paper (Virago, 1980, since reprinted)

OTF

Over the Frontier (Virago, 1980, since reprinted)

TH

The Holiday (Virago, 1979, since reprinted)

CP

The Collected Poems of Stevie Smith (Allen Lane, 1975, since reprinted by Penguin)

MA

Me Again: Uncollected Writings of Stevie Smith, edited by Jack Berbera and William McBrien (Virago, 1981, since reprinted)

BBC WA

BBC Written Archives

U of H

University of Hull

U of T

University of Tulsa, Special Collections, McFarlin Library

U of N

University of Neuchâtel

U of R

University of Reading

WUL

Washington University Libraries

KCC

King’s College, Cambridge

PGP

Palmers Green Papers, letters and documents in Stevie Smith’s possession at the time of her death and now belonging to her literary executor, James MacGibbon

Introduction to the Revised Edition

‘My whole life is in these poems . . . everything I have lived through, and done, and seen, and read and imagined and thought and argued.’1 These are encouraging words for a biographer. But reader, be warned, the relationship between Stevie Smith’s life and work is not nearly as transparent as this might suggest. Her poems are alive with many voices which resist the notion of any essential self. Some carry echoes of fairy tales and myths; others are given to animals and to characters of both sexes and all ages; many explore what Seamus Heaney has called ‘the longueurs and acerbities, the nuanced understatements and tactical intonations of educated middle-class English speech’.2 Always the voice is burnished into a persona that is detached from its author. It is also strong and distinctive, having, as Philip Larkin observed, ‘the authority of sadness’.3

It is, however, true that her fictional character, Pompey, as encountered in Novel on Yellow Paper (1936), comes close to being a self-portrait. Not only can an exact parallel be found between Pompey’s circumstances and those of her author, but Pompey’s lively, gossipy manner is very similar to that found in letters which Stevie Smith wrote at around this time. Some of these letters were published at the tail end of Jack Barbera and William McBrien’s Me Again (1981), a selection of hitherto uncollected writings by Stevie Smith. It was after reading these, and perceiving the rich dialogue between her life and work, that I wrote to James MacGibbon, her literary executor, asking for permission to write a biography of Stevie Smith. In time, of course, I came to see that there is no simple equation, even between Pompey Casmilus and Stevie Smith, for Pompey’s bravado ignores the complexities in Stevie’s own character. What gradually emerged as I wrote this book was a clearer understanding of the artistry and imagination that enabled Stevie Smith to transform her thoughts and experiences into the realm of art. Much of this biography is therefore about that creative process.

In my previous introduction to an earlier edition of this book, I noted that critical opinion on Stevie Smith’s achievement remained unsettled, lacked consensus. This still remains true. Newspaper editors continue to plunder her most famous poem ‘Not Waving but Drowning’ for their by-lines; her poems resurface in anthologies and are read in schools; and the Oxford Professor and leading literary critic, John Carey, at the time of the millenium, listed The Frog Prince and Other Poems in the Sunday Times as one of the ‘Books of the Century’. But academics, on the whole, continue to fight shy of her work and its teasing ambivalence. Though in 1997 Sanford Sternlicht published a collection of critical essays on her work, under the title In Search of Stevie Smith, most had been written ten or more years before. Academic discussion of her work has, however, been advanced by the publication of two books, Laura Severin’s Stevie Smith’s Resistant Antics (University of Wisconsin Press, 1997) and Derk Frerichs’s Autor, Text und Kontext in Stevie Smith’s Lyrik der 1930er Jahre (Bochum: Projeckt, 2000), and through two articles, by Sheryl Stevenson and Romana Huk, in the University of Wisconsin’s periodical, Contemporary Literature.4 I can also mention the 1987 biography of Stevie Smith, by Jack Barbera and William McBrien (who became for me the most friendly and courteous of rivals), and yet still remain confident that in my own book can be found insights into Stevie Smith, the poet, novelist, broadcaster and reviewer, that are available nowhere else.

Only recently have feminists begun to acclaim her. This is surprising, for her relish for parody inscribes her disaffection with many of the masculine traditions she inherited. Moreover, the unexpected twists that she gave to certain myths and fairy tales prefigured the feminist interest in recasting familiar narratives, while her use of the Grimm Brothers’ tales set a precedent for Anne Sexton’s Transformations (1972), which retells sixteen stories from Grimm, and Liz Lochhead’s The Grimm Sisters (1981). But, as Martin Pumphrey argues,5 Stevie’s poetry is easier to patronize than to engage in debate. It is also difficult to categorize and often hard to explain how she achieves her effects, at times teasing and flippant, at others, powerfully serious. Although there are poems in which the syntax is fragmented and compressed and where the influence of Eliot can be detected, modernism was not her chosen inheritance. Instead her poetry ranges freely over associations connected with older traditions, forms and genres. She picks up rhyme schemes and metrical contracts only to abandon them when she shifts her tone or idiom arrestingly. Similarly her diction switches abruptly from the biblical and portentous to colloquialisms, clichés and slang. Her love of ambiguity makes it sometimes difficult to know whether a literary influence or convention is being leaned on or parodied. This cunning exploitation of a range of tactics can give us a poem that is dense with poetic allusion and another than has a childlike directness. Often an absence of complex metaphor is combined with a diction that is simple, flat and poignant, the words positioned in such a way as to give them an extraordinarily large and suggestive power.

This may explain why her work has appealed to musicians, to Elisabeth Lutyens, Stanley Bate, Gordon Crosse, Peter Dickinson, John Patrick Thomas, Robin Holloway and John Gardiner, all of whom have set poems by her to music. Stevie, herself, frequently had a tune in mind when she composed her poems, some of which she sang in performance. And though she never upheld euphony over meaning, she referred to her poems as ‘sound vehicles’.6

Her aim was to write poetry that comes to the lips as naturally as speech. In this she was an inheritor of a tradition that looks back to the Lyrical Ballads and beyond. But her liking for simplicity, her refusal to overdecorate her themes, is, as I have suggested, only one aspect of her poetics. Another is her constant use of quotations, half-quotations, travesties, echoes and allusions drawn from the work of other poets whose voices infiltrate her own. ‘The accents are those of a child,’ Christopher Ricks has written; ‘yet the poems are continually allusive, alive with literary echoes as no child’s utterance is.’7 Her auditory imagination, initially fed by learning poetry at school, was sustained by intensive reading. John Bayley has observed that her poems ‘have in their own way as much disciplined digestions behind them as those of Yeats or Valéry’.8 She wears this learning lightly and makes shrewd use of her sources. Some of her poems are translations, strictly or freely rendered; others rework famous legends, plays or tales, sometimes arriving at their meaning through a reversal of convention. Her Frog Prince, for example, is content to be under a spell and fears disenchantment; her Persephone, likewise indicating a fear of life, prefers the underworld.

Even her metric is hard to pin down, and at times may or may not be there. Partly because she aimed in her poetry at ‘memorable speech’, she more often than not avoids the formality of a too consciously present metre. Instead she relies on rhyme, cunningly and variously deployed, and on rhythm, that of speech and of thought itself. Hermione Lee has listed internal rhymes, alliterations, startlingly concentrated monosyllables and repetition of simple key words as some of the things that buttress Stevie Smith’s lines from within.9 Punctuation is not a key tool and is sometimes absent. To a friend, Stevie once wrote: ‘Punctuation continues to bother me, so if you find anything odd about it in these poems, do say so, please! Oddity, I assure you, is never intentional.’10 Considerations of syntax and punctuation, Michael Schmidt argues, are overridden by her handling of rhythm. It is for him her most striking characteristic.11

Because Stevie Smith refused to construct a single authoritative voice, her work remains multivocal and contradictory. It upholds her belief in the necessity of paradox and inconsistency. ‘In Lear’s mind run also the Fool’s iconoclasms,’ she once wrote.12 This duality features in her own poetry with its blend of the tragic and the comical. Renowned for her humour, she nevertheless demonstrates time and time again a refusal to turn away from pain. One of the most appreciative critics of this aspect of her work was Richard Church. ‘I admire her work,’ he wrote, ‘both in prose and verse, because it is a garment worn with courage and a tragic spirit. The tragedy is there because in almost every phrase she utters, not excepting the many witty and hilarious ones, her purpose is to explore the cavities of pain and to find a way out of their horror and darkness.’13

Like others before me, I have found it necessary to refer to my subject as ‘Stevie’, the name by which she was familiarly known. This is partly because it would be too laborious to use her full name in every instance and too impersonal to use only her anonymous surname. Stevie herself advised against the pomposity that clings to the latter choice, by remarking that when surnames alone are used of contemporary male poets it sounds as if they have all been raised to the peerage.

The artist Georgia O’Keefe once said: ‘Where I was born and where and how I have lived in unimportant. It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest.’14 It is a remark that, as Stevie Smith’s biographer, I have tried always to keep in mind.

Frances SpaldingLondon, 2002

***

Since 2002, when the above introduction was written, several publications and performances have helped enhance Stevie Smith’s reputation. And it is no longer true to say, as I did back then, that ‘academics, on the whole, continue to fight shy of her work and its teasing ambivalence’. I can verify this by mentioning the very lively Stevie Smith conference, titled ‘Parrots Ate Them All’, at Jesus College, Oxford, on 11 March 2016. The organiser Noreen Masud invited Hermione Lee and myself to give introductory presentations. Two years later, Noreen Masud and Frances White edited, for the magazine Women: A Cultural Review, a Special Issue (Volume 29, Issue 3–4, 2018) titled ‘Re-Reading Stevie Smith’. Out of these seven essays spilled much original thought on Stevie Smith. It went online on 6 December 2018.

2019 saw a new edition of Hermione Lee’s Stevie Smith, A Selection, which had first appeared in 1983, as an introduction to this poet. The publisher, Faber, now referring to Stevie Smith as ‘an idiosyncratic English genius’, had recently been successful in taking over her Collected Poems from Penguin. Recognising that they needed refreshing, Faber invited Will May to act as its editor, his PhD on Stevie Smith having fed into his book Stevie Smith and Authorship. And because the new edition included more drawings than had been found in its predecessor, it was given a new title: Collected Poems and Drawings of Stevie Smith. An important and influential review of it, by Angela Leighton, appeared in the Times Literary Supplement (19 February 2016).

In 2019 Noreen Masud published an essay, ‘Aphoristic Interruption in Stevie Smith’, in Aphoristic Modernity: 1880 to the Present, edited by Kostas Boyiopoulos and Michael Shallcross. The richness of thought it contained was pursued further in her book Stevie Smith and the Aphorism: Hard Language, published by Oxford University Press in 2022. Its bibliography contains many references to the writings of others about Stevie Smith and it is therefore probably the most up-to-date source for recent studies on her work. So – ‘Read on, Reader, read on and work it out for yourself,’ as Stevie advised.

Not to be forgotten is Zoë Wanamaker’s telling performance as ‘Stevie’, in the play of that name by Hugh Whitemore, which was directed by Christopher Morahan at the Hampstead Theatre in 2015. Equally moving was the way Juliet Stevenson brought Stevie Smith’s poetry to life in the film, made by Dead Poets Live and shown at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in 2021, on the fiftieth anniversary of Stevie’s death. Finally, on a more personal level, I will never forget the Stevie Smith poetry reading we did – Zoë Wanamaker, Will May, Rachel Cooke and myself – at King’s Place, London, to a sell-out audience, on 23 February 2016.

Frances Spalding2025

CHAPTER 1

From Hull to Palmers Green

Reading her poems at the Edinburgh Festival in 1965, Stevie Smith received warmer and more immediate applause than that given to W. H. Auden. There was a startling incongruity between her small person, prim dress and apparent helplessness (she had to beg a pair of spectacles from her audience) and the steely, ironic entertainment she delivered. Recognition had come slowly to her, snowballing during the last decade of her life as she became part of the 1960s poetry boom, a star of the poetry-reading circuit. By then the character she had created for herself, beginning with the appearance of Pompey in Novel on Yellow Paper in 1936, had become indelibly fixed. One fact that she promoted was her unchanging address. ‘Born in Hull. But moved to London at age of three and has lived in the same house ever since.’ So she told Peter Orr when he was editing transcripts of recorded interviews with poets. ‘I started on the biographical note, which you asked for. But it didn’t get very far, as you see.’1

It surprised her friends that, living with her aunt in Palmers Green, Stevie Smith could find material for poetry in such restricted circumstances. She recounts the history of her home and its inhabitants in a late poem, ‘A House of Mercy’, which is accompanied by a drawing of a habitation, apparently in imminent state of collapse. In the first four stanzas the poem likewise teeters between the anti-poetic and a language evocative of ballads, fairy tales and romance.

It was a house of female habitation,

Two ladies fair inhabited the house,

And they were brave. For although Fear knocked loud

Upon the door, and said he must come in,

They did not let him in.

There were also two feeble babes, two girls,

That Mrs S had by her husband had,

He soon left them and went away to sea,

Nor sent them money, nor came home again

Except to borrow back

Her Naval Officer’s Wife’s Allowance from Mrs S.

Who gave it him at once, she thought she should.

This blurring of genres allows mythical overtones to accrue: facts concerning Stevie Smith’s life take on a fictional air. ‘Who and what is Stevie Smith?’ asked Ogden Nash. ‘Is she woman? Is she myth?’ As the poem moves towards an affirmation of strength in the last two stanzas, there is a noticeable increase in formal control and a display of rhythmic felicity.

Now I am old I tend my mother’s sister

The noble aunt who so long tended us,

Faithful and True her name is. Tranquil.

Also Sardonic. And I tend the house.

It is a house of female habitation

A house expecting strength as it is strong

A house of aristocratic mould that looks apart

When tears fall; counts despair

Derisory. Yet it has kept us well. For all its faults,

If they are faults, of sternness and reserve,

It is a Being of warmth I think; at heart

A house of mercy.

Paradoxically Stevie Smith’s rooted existence allowed her to become a poet of alienation, orphanhood and loneliness; to imbue her work with, Seamus Heaney argues, ‘a sense of pity for what is infringed and unfulfilled’.2 The tragic note sounded in her work is, however, made buoyant by a humour that keeps despair at bay; breezy commonsense, shrewdness and stoicism combat melancholy. Nevertheless her stark moral sense denied her comforting illusions and drove her to confront stupidity and cruelty, loneliness and loss. ‘Here is no home, here is but wilderness,’ is a line by Chaucer to be found in her Batsford Book of Children’s Verse (1970). Her poems are full of characters who are not at home in this world, who ‘walk rather queerly’ or give signals that are not answered. ‘We carry our own wilderness with us,’ remarks Pompey in Over the Frontier.3 ‘Celia,’ says another, in The Holiday, ‘you have always said that we are in exile in this world and must long for home.’4 Reviewing the memoirs of Prince Serge Obolensky, Stevie Smith remarked that he became ‘almost too much at home, and in a world really where one should not feel at home; too blunted, too destroyed’.5 With laughter always in close attendance upon her thoughts, she herself remained indestructibly sharp, pitifully alive. ‘Learn too’, she once wrote, ‘that being comical / Does not ameliorate the desperation.’6

Florence Margaret Smith was born in Hull on 20 September 1902. Not until the 1920s, when riding over a London common, did she acquire the name ‘Stevie’: some boys called out ‘Come on, Steve’, alluding to the well-known jockey, Steve Donaghue, whose fringe stood on end when he rode, and the friend with her thought the name apt. Steve became Stevie, a sobriquet that took over from ‘Peggy’, the name by which up till then she had been known to family and friends. She had one sister, Molly, who was almost two years older. Whereas Molly was christened Ethel Mary Frances in Hull’s most prestigious Anglican church, Holy Trinity, Peggy was baptized at home on 11 October 1902 owing to her critical health. ‘The doctor had given up all hope,’ her mother recorded, ‘but she began to improve this very night and thank God continued to do so.’7

Delapole Avenue, where the Smith family lived, is a narrow street in West Hull composed of two-storey, terraced houses. No. 34 is a modest but substantial house, having four bedrooms and a small back garden. The elaborate mouldings still visible in the hall attest to the fact that Hull was then a prosperous city which had, during the second half of the nineteenth century seen an enormous increase in trade. Between 1850 and 1876 the tonnage of ships entering Hull docks had increased from 81,000 to 2,258,000, an increase that caused considerable congestion in the docks and warehouses and led to the opening of the Alexandra Dock in 1885 and the breaking of the monopoly of the North Eastern Railway with the introduction of the Doncaster to Hull line. This increase in trade had attracted to the city a large immigrant community, creating problems of overcrowding and, in slump periods, unemployment and destitution. By the end of the century, however, a generation of reformers had effected improvements in all spheres of life and, owing to the work of the architect Alfred Gelder, the city was being transformed into a place of pomp and circumstance. The year after Stevie was born Victoria Square was opened by royalty, Queen Victoria’s statue unveiled and the foundation stone laid for the present-day City Hall.

Stevie Smith never knew her maternal grandfather, John Spear, for he died the year before she was born. Nevertheless his presence was remembered owing to the legacy he left which funded her early years and paid for her schooling. Born in 1844, the son of a Devonshire yeoman Christopher Spear and his wife Ann Hearn, John Spear almost certainly began his career by going to sea before becoming a shore-based civil servant, a surveyor with the Board of Trade, first in Newcastle-upon-Tyne where his elder daughter, Margaret, was born in 1872, and that same year moving to the Posterngate office at Kingston-upon-Hull. In addition, he was chief engineer to the Royal Naval Reserve, probably in the Humber section. His job as a surveyor entailed the overseeing of vessels, particularly their engines, to determine whether they were seaworthy. He also acted as examiner of engineers. By 1882 he was well enough established to live in one of the fine Victorian houses that lined Park Street, with his wife, Amelia Frances, and two children, Stevie’s mother, Ethel Rahel, having been born in 1876. By 1885 he had become principal surveyor at the Board of Trade offices. Four years later he left, after seventeen years’ service, to take up a post elsewhere. His colleagues presented him with a gilded testimonial which, all Stevie Smith’s life, hung in the hallway at Palmers Green.

John Spear left the Board of Trade to become a superintendent engineer with the shipping company Thomas Wilson and Sons. ‘Hull is Wilsons and Wilsons are Hull’ was the then popular Yorkshire expression. The firm had begun importing Swedish iron ore in the 1820s; after the death of its founder in 1869, Thomas Wilson’s sons expanded its fleet and trade routes, even westwards to America though geographically Hull is less well placed for these routes than other British ports. When John Spear joined the firm in 1889 it had a fleet of more than fifty ships and was on its way to becoming the world’s largest privately owned shipping company. Spear would again have been responsible for repairs and maintenance and for the appointment of seagoing engineers. He probably attended when new ships were being built and would certainly have been on board when they underwent trials. A man with considerable responsibility, he was regarded with pride by his family, up until Stevie’s death a photograph of him in dress naval uniform ornamented the sitting room at Palmers Green.

John Spear had a sister, Martha Hearn Spear, who married Issac Clode of Sidmouth in Devon. After his wife died, Spear appointed Martha Hearn Clode one of three trustees of his estate, in the even tof him dying before his daughters came of age. She is named in Stevie’s poem, ‘A House of Mercy’ and is probably the original for ‘Great Aunt Boyle’ in The Holiday. In this book Stevie recounts tales of her ancestors by reporting conversations that ‘Celia’, the narrator, has with her aunt. It remains our sole source of information on relationships within the Spear family, and though presented as fiction can be taken as fact, for Stevie’s autobiographical writing is always true to the situation, if selectively and obliquely told.

In The Holiday Great Aunt Boyle urges Celia’s grandfather to remarry. John Spear was only forty-three when his wife died and, having worshipped her, he refused to marry again. ‘But he was a moody sad man after her death,’ The Holiday tells us, ‘she was so wise, and with a sure touch could draw the right people around her, and keep the sad moods away from him.’8 He apparently lost confidence in himself and felt that if he walked into a room others walked out of it. His loss of equilibrium allowed ‘a poor sort of acquaintance’ to congregate in the family home, to drink whisky, play whist and smoke until two in the morning. At the same time he grew irritated with his younger daughter whose melancholy matched his own: ‘she was silent when he rounded on her, and grew so sad and dreamy that he could not bear it.’9 He antagonized her further by laughing at her fancies and at her paintings. Though the elder sister took on the care of the house and the management of the two servants, the sisters were still in need of parental advice which they did not get.

‘And if your mother and I asked him: “Shall we go to this place or to that? Or have these people to dinner, or those?” he would say: “You must decide for yourselves.” But we were too young to decide wisely. And so your mother met your father and married him.’10

Stevie, influenced by her aunt, retained the notion that her parents’ marriage was the result of unfortunate circumstances. It is touched on, its drama reduced to light romance, in her first prose work, Novel on Yellow Paper.

‘When my mama was a girl she was being rather romantic, and so she made an unsuitable marriage. My aunt used to say: If your grandmother had lived your mother would never even have met your father.’11

Ethel Spear was twenty-two when she married Charles Ward Smith on 1 September 1898. He was twenty-six, and a forwarding agent in his father’s offices in Fish Street in the ‘Old Town’ part of Hull, down towards the ferry pier and the riverside. This part of town still had many medieval, half-timbered buildings; its market place boasted a gilded equestrian statue of William IV as well as Holy Trinity church where Charles and Ethel were married. As seen at night, this area has been memorably recorded in the paintings of Atkinson Grimshaw. Along the edge of the Old Town the tidal river Hull flowed into the Humber and was crossed by North Bridge, which remained up at high tide so that ships arriving from Russia and Scandinavia could sail right into the heart of the city.

Charles Ward Smith’s father, Charles Smith, was born in Louth, Lincolnshire and had been a part of the large migration from the North Midlands and other parts of Yorkshire to Hull in the second half of the nineteenth century. There he married Mary Ward and found employment as a shipping agent’s clerk. He then set up on his own as a shipping and forwarding agent, work that involved arranging the import and export of goods carried by sea, compiling ships’ manifests and arranging custom fees. In 1876 he bought the lease on 54 Lister Street, fairly fashionable address where he is shown living with his wife in the 1881 census records. Five children are listed as present in the house at the time the record was made, when it would seem that the two eldest children, Charles Ward Smith and another, were elsewhere. Charles Smith appears to have profited from the rapid growth in certain mercantile sections, accompanying the improved dock facilities, because while still living at 54 Lister Street he acquired two further properties, 17 and 18 Paradise Place. These he disposed of in 1887, which is perhaps the first evidence that his business had begun to decline. However, he continued to act as a shipping and forwarding agent and in 1901 added insurance and coal export to his firm’s description. The insurance of ships’ cargoes would have been a logical addition to his work as a forwarding agent, the other addition made possible by the large quantities of coal coming through Hull as a result of the development of the Yorkshire coalfield and the expansion of railways.

Charles Smith’s son, Charles Ward Smith, knew from childhood that he wanted to go to sea. As a boy he did well at languages. It was agreed that he would enter the Navy on leaving school, but when one of his brothers, as Stevie recounts in Novel on Yellow Paper12 (if not two, as she told Kay Dick13), was drowned at sea, his mother forbade it. He was directed instead into his father’s business which, by 1903, was registered as Charles Smith and Sons. According to his daughter Molly,14 he let the business run down and go bankrupt owing to his lack of interest and the adverse effect of an economic depression. His father was unable to help. Charles Smith still owned 54 Lister Street though in 1897 he had moved to Westwood, one of the large semi-detached villas overlooking Pearson’s Park. But by 1901 he had moved to Bridlington, to a house he did not own, and in July 1906 he mortgaged 54 Lister Street to the York City and County Bank as security for debts. By 5 February 1907 these debts had clearly not been paid as a deed of foreclosure gave the bank possession of this security. The bank’s records show that by the end of 1906 Charles Smith owed £507. 12s. 0d. and that the ‘estimated value of securities and dividends to be realized’ was £300. Accordingly the bank provided for a loss of £207. 12s. 0d. on the account, and the manager explained in his December report that the loss was ‘caused by depreciation of property formerly worth £600, now sold for £300’.15 The bank’s records do not refer to bankruptcy, but as it was prepared to accept such a relatively large loss on the sale of the security, it seems sale to assume that by the end of 1906 the firm Charles Smith and Sons was no longer trading.

This date tallies with Molly Smith’s claim that her father ran away to sea when she was five and Stevie three.16 He had wanted to join the Navy during the Boer War but family pressure prevented him from doing so. Frustrated, unhappy, and with little sense of responsibility, he left home. Stevie was convinced she was partly to blame. ‘Poor Daddy took one look at me and rushed away to sea,’ she told Kay Dick,17 an idea she promotes in her poem ‘Papa Love Baby’.

What folly it is that daughters are always supposed to be

In love with papa. It wasn’t the case with me

I couldn’t take to him at all

But he took to me

What a sad fate to befall

A child of three

I sat upright in my baby carriage

And wished mama hadn’t made such a foolish marriage.

I tried to hide it, but it showed in my eyes unfortunately

And a fortnight later papa ran away to sea.

After Charles Ward Smith disappeared (he joined the White Star Line as pantry boy and rose to the position of assistant purser), his wife and children had to survive on John Spear’s money. Molly Smith recollected that they moved south because they could no longer afford the house in Hull.18 But the difference in size between 34 Delapole Avenue and 1 Avondale Road is not so great as to explain fully this move, or the haste with which it was made. Perhaps the desire to escape the gossip of neighbours and friends was a motive. Almost certainly the marriage had broken down before Charles Ward Smith went to sea, and his departure was merely a way out. More than sixty years later, when she summed up the situation for Kay Dick, Stevie recollected: ‘Not happily married – he wanted a career at sea. When I grew up I realized it was what’s called an unsuitable marriage, but he used to come home on leave. My mother was immensely loyal; no word was ever said against this creature, and appearances were kept up.’19 As can be seen, Stevie gave her affections to her mother but in her poetry was to identify herself, if only subconsciously, with her father, making the theme of journeying an important one. Charles Ward Smith maintained his presence in their family life by sending postcards, of the briefest sort. ‘Off to Valparaiso love Daddy’, was the one Stevie instanced, adding: ‘And a very profound impression of transiency they left upon me.’20

In some ways, his absence was easily filled. ‘So then it was, and how it was,’ Stevie explains, ‘that my Aunt the Lion of Hull came to live with us.’21 Margaret Annie Spear, known to her friends as Madge and to her nieces as Auntie Maggie, had, at the age of fifteen, taken over the running of her father’s house; now she did the same for her sister, Ethel. Photographs reveal a marked difference in appearance between the two sisters: Ethel smith was pretty and slight, probably already slightly debilitated by poor health; Madge Spear was stalwart, more handsome, her face composed around a strong bone structure. A person of sterling character who all her life retained a Yorkshire accent, she was not an intellectual but shrewd, intelligent, dutiful and commonsensical. In Molly Smith’s autograph album in 1915 she inscribed a line from Dryden: ‘We first make our habits then our habits make us.’22 Whether it was the philosophy this expressed or the neatness of the chiasmus that appealed, she contributed a similar motto to the St John’s Church, Palmers Green, birthday book printed in 1932: ‘If you cannot do what you like, try to like what you do.’

Despite here no-nonsense attitude, Aunt in sentimental mood would sing, ‘In the gloaming, / Oh my darling, / Think not bitterly of me,’ thus commemorating, as Stevie’s persona, Pompey, remarks, ‘the suitors, already no doubt devoured in wrath and digested at leisure’.23 Madge Spear displayed a natural capacity to do without men. In The Holiday Stevie compares her with a Begum: ‘there was no He-Begum in your life, no there was not, Alec Ormstrode [whose real name, Oscar Troostwyck, appears in the manuscript of The Holiday and in postcards sent to the aunt] loved you, but you would have none of him . . . you are the Begum Female Spider who has devoured her suitors and who lives on and makes these crocodile-like pronouncements, and who is like a lion with a spanking tail who will have no nonsense.’24

Her favourite book, Stevie tells us, was The Relief of Chitral (1895), written by two brothers, Captains G. S. and F. E. Younghusband, both of whom had served in his campaign and acted as correspondents to The Times. Ostensibly an objective account of the rising of the Chiltralis against the British, its underlying jingoism loses no opportunity to uphold the British Army as honourable and unquestionably right. It is hard to imagine the woman who took such pleasure in this book, with its maps, diagrams and careful amassing of factual detail, ever indulging in a romantic novel. Her fascination with The Times law reports also suggests a taste for the cut and dry, though it must also be said that reading these reports was at this time the only way that a lady could acquaint herself with the seamy side of life.

It was Madge Spear who found 1 Avondale Road. Once a move had been decided upon, she had gone to London ahead of her sister and nieces, leaving them in Hull waiting to hear what their change of address would be. Not until the last minute did a telegram arrive, and by then the new owners of 34 Delapole Avenue were anxious to move in and the Smith furniture already packed, the men waiting to drive it away. Arriving in the north London suburb of Palmers Green one afternoon in September 1906, the children were pleased to discover, as they finished their journey by tram, that they had in fact exchanged the town for the country, for Palmers Green was still attractively rural and a motor car a very rare sight. 1 Avondale Road, a modest, red-brick, end-of-terrace house, trimmed with white facing and with a small garden in front and behind, greatly pleased Molly and Peggy Smith. It had, however, obviously been found in haste: Miss Spear refused to sign the lease on it for longer than six months assuming it would be merely a temporary home.

Shortly after they arrived three-year-old Peggy Smith was taken round to a neighbouring plumber in order that she could be weighed. When she told him, in a thick Yorkshire accent, how she had travelled on a train and then on a tram, he replied, ‘Why you’re a furriner, you’re a foreign package’.25 Speaking more accurately than he knew, he then lifted her down from the scales.

Palmers Green was originally a tiny hamlet, a mere collection of houses and cottages clustered together at the point where Hazelwood Lane runs into Green Lanes, the main road leading out of London, from Islington to Enfield and which, during the early nineteenth century, had become a popular excursion route, as its name implies, for Londoners in search of beautiful countryside. Apart from the building of some large villas to the west of Green Lanes, between Fox Lane and Hoppers Road, Palmers Green remained virtually unaltered right up until the end of the nineteenth century. Even the advent of the railway had brought little change, for the area was protected by owners of large estates who refused to carve up their land and therefore kept the speculative builder at bay. Some building did begin in the 1890s. Then in 1902 Captain J. V. Taylor of Grovelands sold large tracts of his land for development. After this more and more land came on to the market and suburbia spread.

Already by 1906, when Stevie and her relations arrived, Green Lanes was entirely lined with shops and houses. The surrounding fields, country lanes and toll gate that gave the area its charm were steadily diminishing with the spread of bricks and mortar, pavements and privet hedges. Long-standing residents in the larger villas began to express fears in the local magazine, the Recorder, that as a result of all this building a poorer class of resident would be attracted to the area. Shopkeepers in Alderman’s Hill complained about the muddy state of the road and the need for more pavements, for it soon became apparent that the existing road system was far from adequate. In just ten years, between 1901 and 1911, the population in the district of Southgate, which includes Old and New Southgate, Palmers Green and Winchmore Hill, rose from 14,993 to 33,612. The rapid influx of population put pressure on existing services; by the summer of 1908 the Metropolitan Water Board was having difficulty in maintaining adequate pressure in the mains for Winchmore Hill and Palmers Green. And though the district was still without electricity, negotiations for gas began that year.

Very quickly Palmers Green developed a reputation for being one of the most snobbish of London’s outer suburbs. It was attractive to those wanting to move to a better class of district than Hackney or Wood Green. Advertisements in the local press for ‘artistic villas’ in Palmers Green stress the healthiness and convenience of life in the suburbs. The political flavour of this up-and-coming residential area was already noticeably right wing. A Palmers Green Conservative and Unionist Association was formed in 1907, and when a Liberal MP, James Branch, a Nonconformist shoe manufacturer from Hackney who had narrowly won his Enfield seat in the 1906 election, spoke at Palmers Green in 1909, he had a bag of rubbish thrown at him. The tone of the area is reflected in the correspondence columns of the local press, where a persistent demand for better services from Southgate Urban District Council is coupled with a violent antipathy to paying for these services in increased rates.

The residents of Palmers Green took pride in their wide-fronted shops and in the dignity of its larger villas, some with garages and carriage sweeps. Despite the rapidity with which a quiet, rural area was transformed into a bustling suburb, the area quickly established a settled, rather self-congratulatory air. In 1921 it was gently satirized by Thomas Burke in his book, The Outer Circle, which records his travels, by bus, through outer London, as he passed from Wood Green into Bowes Park and from there into Palmers Green:

‘If Bowes Wood is Wood Green in Sunday clothes, Palmers Green is a Bowes Park that has “got on” . . . There is an austere flavour about it: a fine serenity, almost serendipity. In its streets one becomes chastened, yet not humiliated. No little half-hearted shops here . . . No barbers at all – hairdressers only. No drapery stores or baby-linen shops; but veiled, contemplative establishments with empty windows, labelled Odette or Julie or Yvonne – ladies whose presence in a suburb is a cachet of social rightness. Folk don’t let themselves go in Palmers Green. The word “jolly” is never used; its synonym is “charming” or “delightful”. Children on scooters proceed along its pavement with almost Chinese placidity. Everybody proceeds. Even the butchers’ carts proceed.’26

In an area where social differences were sharply observed, the straitened circumstances at 1 Avondale Road, where there was no maid or servant of any kind, would not have gone unremarked. Yet Palmers Green snobbery, Stevie later averred, gave zest to life and was fairly harmless. There was sufficient money from John Spear’s legacy for Stevie and Molly to attend a fee-paying local school. It was a cut above the County School in Fox Lane and the Board School in Hazelwood Lane and placed them, not unhappily, among children on the whole better off than themselves.

Even in this benign area, Stevie as a child soon learnt a sense of dread out of key with the surrounding social brightness. Two elderly ladies lived next door and one of these kindled her imagination with talk of the White Slave Traffic. She also took the small child on afternoon walks to a nearby cemetery. ‘These graveyard excursions,’ Stevie recollected, ‘fired me later on to write a very solemn poem.’27 It begins:

The ages blaspheme

The people are weak

As in a dream

They evilly speak

Their words in a clatter

Of meaningless sound

Without form or matter

Echo around.

For the most part, however, Stevie associated her childhood with the mellow warmth of September sunshine:

‘This sunny time of a happy childhood seems like a golden age, a time untouched by war, a dream of innocent quiet happenings, a dream in which people go quietly about their blameless business, bringing their garden marrows to the Harvest Festival, believing in God, believing in peace, believing in Progress (which of course is always progress in the right direction), believing in the catechism and even believing in that item of the catechism which is so frequently misquoted by the careless and indignant . . . “to do my duty in that state of life to which it shall please God to call me” (and not “to which it has pleased God to call me”); believing also that the horrible things of life always happen abroad or to the undeserving poor and that no good comes from brooding upon them.’28

The building of churches helped establish the community life of the area. St John’s, Palmers Green, the Anglican church to which Mrs Smith and Miss Spear belonged, was built in stages between 1904 and 1909. Not long after its completion a large Roman Catholic church, St Monica’s, went up in Green Lanes. Both played an important social role, St John’s in particular, for its church hall hosted society meetings and, during the First World War, a great many concerts, plays and bazaars in aid of charity. As a child attending regular services at St John’s, Stevie grew familiar with the Psalms, Hymns Ancient and Modern and biblical tags. She might not always sing the same hymn as everyone else, but she knew her catechism and the Bible stories, having been trained in both by Miss Fanny Schubert who ran the Sunday School. She also retained a conviction that ‘there is cheerfulness and courage in the church community, and modesty in doing good.’29

With the religious needs of the area catered for, secular entertainment swiftly followed. The first cinema in the Palmers Green area opened in 1912. Much entertainment was home-grown; societies and clubs flourished. The area had its own branch of the Fabian Society which on one occasion was visited by Mrs Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia, probably because they had a link with these parts through Mrs Pankhurst’s brother, Herbert Goulden, who lived in Winchmore Hill. Even in Palmers Green the issue of women’s suffrage could not be ignored. Near to Stevie’s home, in Stonard Road which cuts across the top of Avondale Road, lived two suffragette sisters, one of whom went to prison after a window-smashing expedition in Oxford Street and who must have been the talk of the district. In addition, Lady Constance Lytton came to speak on the women’s question to Palmers Green Literary Society, to which Stevie’s mother belonged. In April 1910 Mrs Smith entered a short-story competition and won a prize. This Literary Society met once a month, on the Monday night nearest to the full moon. One of its visiting speakers lectured on the moon, with Stevie, still a young child, in the audience, listening enthralled.

She also enjoyed playing in the nearby Winchmore Hill woods. These lay on the other side of Hoppers Road which runs parallel with Avondale Road, and though Stevie and Molly were forbidden to cross the railway line that edged the woods, they soon found a culvert under the line and crawled through. Here a great many games were invented and trees climbed. Stevie became the leader of a small gang; they enjoyed outwitting the keeper whose business it was to keep children out, for these woods were then still privately owned and trespassers forbidden.

There was also a calmer pleasure to be had in Winchmore Hill woods. Here began Stevie’s lifelong love of trees and water. ‘Paradise’, she recalled, ‘. . . was that part of the wood which lay just behind the railway cutting, an open pleasant place it was with a little stream, all open and sunny as the day itself. But behind that again lay the dark wood, with the trees growing close together, the dark holly trees, the tall beeches and the mighty oak trees.’30 This oasis, reminiscent of the approach to Milton’s Paradise, gained in preciousness as parts of the wood became parcelled out and the trees marked for cutting down. All her life Stevie had reason to be grateful to Southgate Urban District Council for stepping in when part of Captain Taylor’s estate was withdrawn from a sale at which it had failed to reach a satisfactory price. In 1911 the Council bought sixty-four of these acres, later increasing their holding to ninety-one acres, thereby creating the public park, Grovelands.

Though the park contains a coppice wood and a large lake, it roomy and varied, it is not distinguished. But here Stevie found that ‘loamish landscape’ evoked in Novel on Yellow Paper and admired by her in the poetry of Tennyson and Thomas Hood. She liked the park best when the weather was wild and the only other people in it were anglers. ‘Nobody’, she once asserted, ‘who does not know and love the English weather will understand the complicated feelings that come to those who walk alone in the damp.’31 Elsewhere she described how the park in wet weather salved claustrophobia:

‘When the wind blows east and ruffles the water of the lake, driving the rain before it, the Egyptian geese rise with a squawk, and the rhododendron trees, shaken by the gusts, drip the raindrops from the blades of their green-black leaves. The empty park, in the winter rain, has a staunch and inviolate melancholy that is refreshing. For are not sometimes the brightness and busyness of suburbs, the common life and the chatter, the kiddy-cars on the pavements and the dogs, intolerable?’32

Stevie never tired of extolling the virtues of Palmers Green, a true suburb, according to her, because it is an outer suburb and not one of the inner ones which have been captured by London. In her own lifetime it grew shabby and down-at-heel and has since her death deteriorated still further. But even before its decline few could share her view: Grovelands which for Stevie was ‘a happy place even when it is raining’33 is a very average park, dull and dreary in bad weather; nor did the colours of Palmers Green, with its windy shopping corners and people attached to dogs or prams, seem to her friends quite so fresh and exquisite. But Stevie doted on the area:

‘In the high-lying outer northern suburb the wind blows fresh and keen, the clouds drive swiftly before it, the pink almond blossom blows away. When the sun is going down in stormy red clouds the whole suburb is pink, the light is a pink light; high brick walls that are still left standing where once the old estates were hold the pink light and throw it back. The laburnum flowers on the pavement and trees are yellow, so there is this pink and yellow colour, and the blue-grey of the roadway, that are special to this suburb. The slim stems of the garden trees make a dark line against the delicate colours. There is also the mauve and white lilac.’34

It was not just the environment of Palmers Green that pleased her: there was also its promotion of ‘briskness, shrewdness, neighbourliness, the civic sense and No Nonsense’.35 She respected the caring, if humdrum, life of the suburbs, and the stalwart reliability of her neighbours. She argued that its community spirit owed much to the fact that the area had its roots in the country: because the inhabitants of Palmers Green had been considerate to the countryside, keeping large oaks and areas of parkland, the countryside, she felt, had in turn been kind to them. For herself, Stevie required of nature, even when chastened into a park, a larger, more impersonal role. It set a challenge –

Alone in the woods I felt

The bitter hostility of the sky and the trees36

– and could create a ‘dark wood’ in which, as in Dante’s, all sense of motivation and direction is lost. The image of the wood in her poetry is often a metaphor for life, both attractive and fearful. More particularly, the ‘dark wood’ is an enchanted realm, where a life of the imagination is pursued at the expense of ties that bind us to a more everyday existence, and from whence there is no return. ‘Those gentle woods of my remembered childhood’, Stevie once reflected, ‘have had a serious effect upon me, make no doubt about it . . . Only those who have the luxury of a beautiful kindly bustling suburb that is theirs [sic] for the taking and of that “customary domestic kindness” that De Quincey speaks of, can indulge themselves in these antagonistic forest-thoughts.’37

Charles Ward Smith’s brief reappearances at 1 Avondale Road did little to absolve him in Stevie’s eyes. As a child she was made aware of his irresponsibility and never forgot how he arrived one bank holiday, when the shops were shut, with a parrot as a present but nothing with which to feed it. The absence of a father, Stevie thought, had a marked effect on her character.

‘. . . most women, especially in the lower and lower-middle classes, are conditioned early to having “father” the centre of the home-life, with father’s chair, and father’s dinner, and father’s Times and father says, so they are not brought up like me to be this wicked selfish creature, to have no boring old father-talk, to have no papa at all that one attends to . . .’38