Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

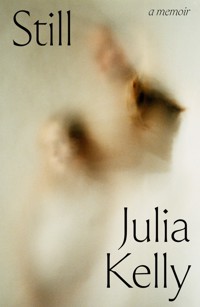

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Julia Kelly's mother, Delphine, spent much of her life in the shadows as a politician's wife, tending selflessly to the needs of her husband, John, and five wild children. Rattling around in a draughty house, the siblings – though much-loved – are left largely to their own devices, tended to by a series of hapless au-pairs, dodging mouse invasions and forever in search of their exhausted mother's attention. When John collapses of a heart attack at the age of fifty-nine, it is a sad liberation for his wife. Unshackled from her domestic duties, Delphine undergoes a transformation. She embraces sea-swimming and, along with a coterie of elderly ladies, sets out on adventures to far-flung places. Her final journey is to the Galapagos Islands where, hit by an unexpected wave, she loses her balance and is forced underwater. When her body surfaces she is no longer breathing. The book left on her bedside locker in the hotel is 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. Mired in grief, the five siblings begin the long repatriation of their mother's body. But it is the post-mortem report that provides the key to Julia's healing and recovery: gradually, within the clinical descriptions of limbs and eyes, heart and toes, Julia finds solace. Taking inspiration from each body part, she breathes life into Delphine – finally still and fully present for the first time in her seventy-two years – in gorgeous, luminous prose. What leaps from the pages of STILL is someone unforgettable: a vibrant, complex woman, whose endless capacity for love continues to inspire and comfort. In the end, She died as she had always strived to live: in the middle of a huge adventure, diving into the great unknown.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 175

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STILL

First published in 2025 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Julia Kelly, 2025

The right of Julia Kelly to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-83594-008-2

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83594-009-9

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Product safety queries can be addressed to New Island Books at the above postal address or at [email protected].

Cover design by Luke Bird

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), Dublin, Ireland.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

For Nick, David, Alexia and Beany

I want to be a wave breaking

On the shores of undiscovered land

–NICK KELLY, ‘HORSE WATER WIND’

Contents

Before

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

After

Acknowledgements

Before

YOU’RE NOT IN THE KITCHEN, WHERE I WANT YOU TO BE. The air smells of your perfume and of burnt toast. On the table there’s a charred crust at the edge of a plate full of scrapings; one of your white hairs is coiled on a knife smeared with marmalade and butter and beside the plate there’s a cheque made out to Member in Charge. It’s payment of a speeding fine; even the letters of your name seem in a rush, the D of Delphine so slanted it’s almost prone.

Punctuality isn’t as important to you as your unspoken determination to arrive anywhere before anyone else, thereby appearing not just dependable but very much on top of things. As well as the cheque, there are two envelopes beside the burnt toast – one for the gardener, the other for the cleaner – addressed in the same rushed hand. Beneath these, in a transparent plastic folder, is the itinerary for your next trip.

It’s the fifth of February 2012, two days before you depart for Ecuador to visit the Galápagos Islands. I can’t remember where you said you would be this morning – aqua-aerobics, someone’s funeral, Ballyogan dump? – because I hadn’t been listening. I used to plead with you to listen to me. I took comfort in your encompassing hugs and your endless reassurance that it would be OK, pet, but I never felt that I had your full attention; your pale eyes were always focused on something beyond me.

‘No, you listen to me,’ my daughter says these days, dominant though diminutive, small hands on small hips. It’s true that my brain takes breaks when people are talking, especially when it’s you about your trips. They are dizzying in their detail and in their frequency. ‘Did I not tell you about the morning we sailed down the Ganges?’ you will begin, and I don’t want to suppress your enthusiasm by saying that you have in fact told me, at least twice, so I let you continue, intermittently nodding and frowning while thinking of other things. Even if I say yes, that you have told me all about whatever trip it was, you will carry on regardless, with brio and a sort of ruthlessness that is becoming more evident as you age.

I fill the kettle the lazy way, through the spout and to the brim. I don’t want tea but I like the reassuring sound of the hot water bubbling and the warmth of its diminishing steam. Above the kettle and hidden behind the old Chinese box containing teabags is an almost empty packet of custard creams. You’ve twisted the wrapper tight, not so much to keep the biscuits fresh but as a way of making them trickier to access. You’ll succumb to them this evening, when you’re alone and sleepy; you’ll jiggle them lightly in your cupped hands while watching the news, occasionally lifting your legs off the footstool and scissoring them vigorously, for a few seconds in mid-air in a desultory attempt at exercise.

I flop down on the bench side of the table, then lie back on its sun-faded foam cushions, causing the dull odour of countless backsides to escape and dust to dance in a funnel of low winter light. Their toffee-coloured covers are identical to the ones we had in our old family home; the table itself seems the same, though its orientation is different. I’d viewed the underside of that table more than the top when I was growing up: I liked to slump beneath it when I was monumentally bored or sulking about some great injustice. In a sloth-like teenage state one day I noticed, while picking at an ancient piece of gum someone had deposited there, that our kitchen table wasn’t actually a table at all but a door: builders’ illegible measurements had been scrawled in red along the edge and there was a circular hollow halfway down where the handle should have been.

The phone rings, which makes me move – not towards it to answer it, but in the opposite direction and out of the room. No one knows I am here, not even you, so I feel under no obligation to pick it up. I’d let myself in; I don’t remember when or why you entrusted me with a key – perhaps it was before your last trip, so that I could punch in the code of the temperamental house alarm if it went off while you were gone, which it always did.

Twice lately you didn’t hear me when I rang the doorbell, immediately presenting my brain with a very plausible disaster, the one I’ve been dreading and predicting since Dad died: that you had collapsed in the garden when trying to start the lawnmower, or choked on a cream cracker while doing your Italian homework, or fell asleep in the bath and slid silently underwater. I continued to catastrophise until you appeared, visibly irritated by my anxiety when you had just gone to spend a penny, for crying out loud.

*

Dad’s death when you were just fifty was a sad liberation for you. It gave you a chance to live the life you had wanted, to come out of your shadowy existence in the kitchen, where you worked in a permanent haze of smoke that seeped from the grease-layered oven you neither had the time nor the desire to clean. Now that you no longer had to cook for your husband, and your children were mostly grown, you could start making some of your own plans and accomplishing things for yourself. Along with the ever-increasing number of stamps on your passport and your diplomas, certificates and degrees, you have accumulated so many friends since becoming a widow that it’s a full-time occupation just to make time for them. You aren’t especially rigorous in your selection criteria and have encouraged the company of some fairly eccentric and tricky human beings. You not only suffer fools, you invite them in and make them a cheese soufflé. Now, as you all age, some of these friends are becoming ill and dying; death has started to follow you around like a miserable inconvenience, getting in the way of your travel plans, stealing people you like in sudden slamming crashes and collapses or in long-drawn-out hospital stays, where you are forced by your sense of loyalty to visit them and watch them becoming bird-like and bald, sunken on pillows and then gone.

‘I’m no good at death,’ you said to me last summer, not wanting to break a commitment to visit a friend in Germany when in Dublin one of your oldest friends was terminally ill and given just days to live. After a lot of badgering from me and my siblings, you cancelled the trip and remained at home till her inevitable death and funeral.

On the next holiday you had scheduled that same summer – to Italy with your children and grandchildren – you were uncharacteristically grumpy and sullen. You adopted a solitary and rigid routine, drinking your milky tea alone on the swing seat in the mornings, having a swim in the pool before the little ones dive-bombed in, and driving to the nearby town to look around the market unaccompanied.

Even this solitude didn’t give you peace of mind. Everything that holiday seemed to anger you: the escalators up to the Etruscan hill town broke down or were turned off without warning or any logic that you could see and you’d had to struggle up the high, immobilised metal steps in forty-degree heat, pausing regularly to catch your breath, creating a queue of impatient, spritely Germans and Americans behind you.

And when you tried to run me over on that holiday I finally knew your anger wasn’t directed at me. I’d asked you to collect some page proofs of a book I was working on when you had finished looking around the market; I’d sent them to the local print shop. You had returned without them and when you saw the disgruntled expression on my face, you looked for a moment like you might slap me. Instead you got straight back into the car and drove towards me at speed. I jumped out of the way, horrified and you kept on driving, along the rickety flagstones of the complex, through the electric gates and away.

You cried when you kissed me on the head that evening, having returned from wherever you had been. You said that your own mother had died at seventy-three, and you were almost seventy-one. It was an odd form of explanation, but I understood. You were annoyed and frightened by the proximity of death when there was still such a lot to do.

*

The trip to the Galápagos is less because of the giant tortoises and more because you have run out of other places to visit. Since the surprise holiday to India my siblings and I gave you for your sixtieth birthday and the subsequent sale of our old home giving you a sizeable income for the first time in your life, your feet have barely touched the ground. You’ve been to China, South Africa, America many times, and back and forth to Europe almost monthly.

You never admit to a fear of flying though you swiftly bless yourself, like you do when passing any church, as the plane rattles and sways and picks up speed and the undercarriage pulls up. Here we go, here we go, here we go, I sing to myself just as habitually at take-off, trying to trick my brain into believing that I’m excited rather than petrified and convinced that I am on a doomed flight, statistics doing nothing to console, nor your reminding me that I would be more likely to die from being kicked in the backside by a donkey. I blame you for this phobia – you and Dad, in fact – two otherwise intelligent and entirely rational human beings who always flew separately as soon as you became parents, so that we would not be left orphaned in the event of a sudden loss of cabin pressure and a hurtling plummet to earth.

*

The rusty old clothes horse is balancing in an A-shape across the top of the bath. Your black Speedo swimsuit is draped over it and dripping. You have baths like others take showers – in and out in five minutes, never lingering, despite the deep water and the capful of Radox that you always add; foam still clings to your damp red ankles while you hurry to get dressed. Your white bathing cap, whose rubbery texture I would have very much enjoyed chewing as a child, hangs off the edge of the clothes horse. It’s embossed with white roses, just like your wedding dress was, and the frosting on your wedding cake. ‘You must deadhead those roses,’ you say in the summer, violently snapping off the wilting petals with your garden-gloved hands, ‘to encourage more blooms.’ You brush the hair from your face with the back of a mud-encrusted, oversized glove, while silently surveying the garden for the next thing to attack.

Now I remember. You said you were going swimming this morning, with your best friend, on Greystones beach – so you’d been back and dashed out again, as you do. Tall, thin, Church-of-Ireland and slow-moving, this woman is the opposite of you in many ways but is the only person you don’t have to adjust your voice for when talking on the phone. You speak instead in a flat monotone, as you would to one of your children, because you are so comfortable in her company.

Your favourite thing is to swim in the sea. You’ve been swimming in it since you first learned, in the inky still water around Garnish Island in Glengarriff, where you would go with your parents as a child. You swim at Greystones as often as you can, undressing at the beach with the insouciance of old age, flat posterior in the air, never bending at the knee, a habit which irritated me enormously and unfairly.

Wearing latex swimming socks to protect your vulnerable toe, the one that’s missing its nail, you pick your way over loose stones towards the sea, looking ahead at the horizon. Chin up, fingertips daintily skimming your thighs, you intermittently flex your hands and turn them out like the ballerina you once wanted to be. You are still graceful despite your full figure, still youthful despite your age. You wade into the water, tentative but silent. Slowly you submerge yourself – feet, knees, thighs – then you’re in, with a contented exhale (you will never admit to the breath-grabbing shock of the cold) and you begin a languorous but effective breaststroke, moving parallel to the shore, neck strained upward, slow and steady, circular rings of glassy water pulsating outwards as you progress. You stay in for as long as you can tolerate the frigid water. Even when your friend is back on the beach, goose-pimpled, with dripping hair and rigorously towelling herself, you still tread water or flip onto your back – isn’t this heavenly, you say, though no one can hear you – and search the cloud-filled sky for the patch of blue you always find there.

*

There’s a draught coming from the bedroom; it’s causing the open door to judder at irregular intervals against its timber frame. I go in, close and bolt the window, grab the cardigan – cashmere, duck-egg blue – that’s hung over the dressing-table chair and put it on. We exist at different temperatures – you forever wanting fresh air, me eternally too cold.

On the bedside table beside an empty mug with a clump of dried milk on its rim is a photograph of my father, in a corroded silver frame. I had a copy of the same photo that I hid down the side of my mattress when he was dying. On the reverse I’d written the things I had never said to him – that I loved him, that I was sorry for being such a pain in the backside and for putting ten years on his life – though I’d whispered all of this in his ear too, when he was curled stiff with rigor mortis. Hearing was the last sense to go, the nurse said.

The open suitcase on the bed is already partly packed. It’s the smallest of your three Samsonite cases, a gift from some of the women you often travel with. The medium and large ones have yet to be used – even though a three-week trip demands more space, you will manage with the smallest; to travel with anything larger you deem wildly impractical and extravagant. You are quietly competitive about this too – needing to be the most sensible traveller in your group.

You have assembled all the clothes you will be taking and have rolled rather than folded them (to prevent creasing and to allow for more space) in colour-coordinated rows. They are mostly made from the silk you bought on your visit to India – it’s wonderfully practical, you always say. You never bothered to use the Colour Me Beautiful consultation you were given for one of your birthdays; you know instinctively the shades that suit you – creams, pale blues, taupes, dusty pinks – and wear trousers that categorically don’t: Lady Diana-style beige chinos, too flesh-like to be flattering, cropped and tapered at the ankle, making you look larger around your middle. You’ve bought T-shirts in five different colours for the trip, from that expensive shop in Blackrock, and will pack one formal outfit just in case – you have hung the various options on hangers outside your wardrobe. When you get home you’ll ask me which one I think would work best (though I know you have already decided), holding the dress against yourself and adopting your mirror pose: chin up, chest out, one leg pointed in front.

All your toiletries are practical too, travel-sized and already in a see-through and sealed plastic bag, ready for inspection at airport security. In a smaller pile, on top of an unintentionally trendy North Face rucksack that must be for hand luggage, are a plastic money belt, a silk scarf for the respectful visiting of chapels and for tying at a jaunty angle around your neck to finish off an outfit (as you always recommend to me – advice that I’ve never once heeded), a new Maeve Binchy novel and those wretched stockings you hate wearing, the ones that prevent deep-vein thrombosis.

In a row along the wall you have lined up several pairs of impossibly small walking shoes and a new pair of runners, navy with white laces. For reasons I don’t understand, the sight of these runners makes me suddenly dread ever having to lose you. Beside these is the ancient tan-coloured case you keep your medicines in. It’s filled with out-of-date and potentially toxic tablets and tonics, its cardboard lid has collapsed and is covered in dust. It was kept out of reach at the top of a mahogany chest in your bedroom for all of our childhoods. I used to balance on a chair and yank it down to help myself to a few chewy orange-flavoured Rubex vitamins when there were no good snacks left in the kitchen.

Unlike most of your once-sporty friends, you have no arthritis and have never been in hospital (all of your five children were born in a nursing home) aside from when your ingrown toenail was removed. You have been trying to get fit ahead of the Galápagos trip. Your best friend doesn’t want you to go; she thinks it’s too challenging a journey for someone who is overweight and has high blood pressure. But you tell her and anyone else who seems concerned that aside from your sea swimming, you have been doing aqua-aerobics twice a week and walking around Blackrock Park for thirty minutes at a time, trying to catch up with walkers ahead of you and sometimes overtaking them.

*

I look at my watch and chew at the side of my thumb the way my father used to do when he was worried. When I try to call you to see where you are, your phone goes immediately to voicemail, which suggests that you are talking to someone rather than that it’s turned off.

Downstairs again, I go into the drawing room, with its airy, under-used feel, and stand at the window wondering whether to wait for you or set off for home. Though it’s a different house on a different street and at a different time, as I stand at the window and look out at the stark trees in the porridge-grey light, hoping to spot you, I’m reminded of the torturous hours we had watched and waited as children for you and Dad to return from wherever you’d gone without us. You travelled without us often and our excitement at your expected return was never about gifts, of which there were often none, or else they were traditional dolls with oddly sparse hair or miniature German dictionaries. It wasn’t even the reprieve your return gave us from the irritating habits of homesick au pairs. What we wanted back was you and Dad in your selves with your coughs and walks, your smells and sounds, and your very particular way of being.

‘You’d swear I was going to the moon,’ you always said when we whined about you leaving. And there we would wait, kneeling at the low dining-room window, focused at first and full of anticipation, hearing the silvery rush of wheels along wet roads of each approaching car, dipped beams lighting up the tarmac ahead and filling us with expectation.

‘Bet you this is them,’ one of us would say when we heard a car slow, our excitement barely containable, a communal giddiness that sometimes caused small accidents. Invariably it wasn’t you; Dad drove very slowly and falteringly in his Fiat 131 and was so hard on the gears that you could hear them crunch as he advanced.