Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

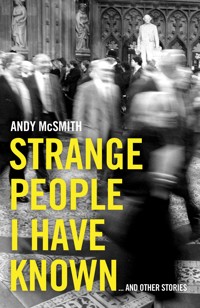

"As well as being one of the leading political journalists of his generation, Andy McSmith's varied life has brought him into contact with a huge variety of people, high and low, whom he describes with an acute eye for character. His book Strange People I Have Known is a fast-paced and entertaining read that brings deep insight into British political life." – Bill Browder "A fascinating memoir which gives a revelatory insider's account of the biggest political names from the past few decades, interwoven with evocative reflections on the many colourful characters who have peppered McSmith's own life." – Pippa Crerar "An addictive memoir that fizzes with anecdotes. If you like top-level political gossip and insights written with panache, look no further." – Gary Gibbon *** Westminster and Whitehall are secret worlds, hidden to most. But working as a lobby journalist, former Labour Party staffer Andy McSmith has had exclusive access to our top politicians for decades. Here, he shares his personal encounters with the great and the good of the British political landscape, revealing what they are really like behind the scenes. With witty and perceptive flair, he describes encounters such as flying to Tokyo with Margaret Thatcher, the last Prime Minister who would walk fearlessly into a room full of journalists, unprotected by special advisers; dining with Sir Edward Heath, a man who knew how to hold a grudge, in his home in Salisbury; observing Gordon Brown and Tony Blair as new MPs, sharing a cramped office in Parliament and collaborating like brothers; and working with Boris Johnson back when he had an ambition to be something more than just a journalist. Filled with vivid portraits of those at the heart of British politics over the past forty years, Strange People I Have Known is a memoir of a life well lived and an insider's account of the inner workings of government.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 572

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STRANGE PEOPLE I HAVE KNOWN

… AND OTHER STORIES

ANDY McSMITH

viTo Tamsin Almeida, whose arrival coincided with events described here in Chapter 18

Contents

Preface

As the past is another country, I am a foreign visitor in today. I come from a land where money is measured shillings, pence and half-crowns, brown ten-shilling notes and green pound notes. Five pounds will fill the petrol tank in your car and leave you with some change. The Queen is young enough to add one more prince to the royal bloodline; there is a John Wayne movie showing this week at the Odeon; and The Beatles are top of the Hit Parade again. You can listen to their singles, EPs or LPs on that bulky piece of furniture that holds your gramophone, but if it’s an LP, don’t forget to switch from 45 to 33 rpm. In the poor, half-hidden suburbs you sometimes see a black person, but the only black people you see on television are the blacked-up singers on The Black and White Minstrel Show.

I also have a blurred recollection of a place where there were ration books, and my mother would walk us to the local community hall to pick up a half-pint bottle of milk, and we would sit together to watch The Woodentops, or Muffin the Mule, on a black and white television that gave off a smell of burning rubber if it was switched xon for too long. Children were not encouraged to listen to or watch the news, but at school, we would be excited to hear about it when another murderer was to be hanged.

Since, I have travelled through times filled with such novelties as colour television, cash machines, dishwashers, phones not attached to a wall and the world wide web.

It was a clever Dane who observed that ‘life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards’. Looking backwards, I see a life strewn with good fortune. Yet at times, I contrived to think I was hard done by as I stumbled through a privileged private school education, which eased me into Oxford University and into a profession that I loved. So I am in no way qualified to write a misery memoir about life on society’s underside; but in late adolescence a heavy cloud of gloom enveloped me. I broke off contact with everyone I had known at school, and almost everyone I had known at university, and then walked out of journalism. But then I wished to return to the trade and had to bluff my way back, at the age of forty, by pretending to be much younger. Along this jagged journey I met some very rare and interesting specimens of the human race. This memoir describes some of them.

1

A Person of Renown

Bratsk. I believe I was the only one in our party who had heard of the place, and what I thought I knew about it was wrong. There was no such town as Bratsk in the 1940s. It was an old Cossack fortress, and a labour camp whose inmates were dragooned into the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway. It became a place you could find on a map in the 1950s, when construction workers dammed the Angara River, created one of the world’s largest man-made lakes and built a hydroelectric power station and a town to house its workforce. That was Bratsk.

We landed there because our aircraft had to refuel between London and Tokyo. The Russians knew that there was a person of great renown aboard our craft and insisted that we disembark and be greeted in the airport’s VIP suite. The formalities were conducted in one room, where the Mayor of Bratsk officiated, while most of our party waited in the adjoining lounge. The floorboards were bare, the refreshments were nil, but there was one extraordinary luxury – a large television screen on the wall, showing Sky TV. 2

To understand how strange this was, consider that no one in Britain had ever seen satellite television until Sky began broadcasting in February 1989. This was September 1989. We were 3,000 miles east of Moscow, watching Elton John perform ‘I’m Still Standing’ in a Siberian town that used to be part of the gulag. It was the first time I realised that programmes could be broadcast simultaneously across continents.

A connecting door opened and Margaret Thatcher entered, having completed her audience with the Mayor of Bratsk, and walked slowly in my direction, smiling, head tilted a little to one side. People look smaller in real life than on television. This extraordinary woman had to, literally, look up to almost every man she met, even if they figuratively looked up to her.

She recognised me as one of the journalists accompanying her but either had forgotten or did not care that I was from the Labour-supporting Daily Mirror. I guess that she reckoned that whoever I was, I was more interesting than the Mayor of Bratsk. Not a high bar, perhaps. Momentarily, I had the Prime Minister’s undivided attention. All I needed was to think of something to say. The best I could manage was to ask how the meeting with the mayor had gone. A slight raising of the eyebrows told me that it had been less than gripping.

‘But did you see the Elton John video on Sky?’ I enquired.

‘No! They were showing the Green Party conference,’ she exclaimed indignantly. ‘That man was saying there is litter in the streets. He can’t say that in a programme that’s being broadcast all over the world.’

That was it. A Downing Street official had spotted the Prime Minister in conversation with a hack and scuttled across the room, 3drawing a predatory pack of journalists in his wake. Still, it was enough for an exclusive on the lines of ‘Furious Maggie Lashes Out’.

Every thinking adult in the UK had an opinion about Margaret Thatcher. She was recognisable like no other Prime Minister since Winston Churchill. I was in a corridor by the open door at the back of a classroom in Tokyo full of Japanese girls aged about fourteen when Thatcher paid them a visit. I could not see her from where I was standing, but I knew exactly when she entered the room because the entire class started screaming with uncontrolled excitement. I doubt that there was any other head of government anywhere who could have provoked that kind of reaction among children in a country halfway across the globe.

In June 1990, Thatcher visited Leninakan, an Armenian city, since renamed Gyumri, which had been partially destroyed by an earthquake two years earlier. An immense crowd poured into the centre of town, filling every square foot of public space. People were waving from windows and standing on the roofs. Behind Thatcher, amid this heaving crowd, was her devoted press secretary, Bernard Ingham, who came from Yorkshire and prided himself on being always on the same wavelength as the man in the pub in Hebden Bridge. There was a risk that Thatcher might be crushed in the melee. With no time to think or choose partners, British and Soviet officials had to link arms in a protective ring around her, and I was vastly amused to see Bernard Ingham arm in arm with a man in the uniform of a high-ranking KGB officer.

Nearby, a line of chauffeur-driven ZiLs waited to take the officials away. I suspect that every government car in Armenia was in that line. A Kremlin doctor and a Georgian photographer were loitering by the vehicles. From them, I learnt that the temperature that day 4was 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) and that the KGB had estimated the size of the crowd at 150,000. Given the number who had moved out after the earthquake destroyed their homes, that suggested that the entire population of Leninakan plus others from the countryside had come for a glimpse of the British Prime Minister.

Thatcher was recognised everywhere she went but not universally loved, especially not in the north-east of England, where I was living when she assumed office in 1979. Working-class communities were already at the sharp end of deindustrialisation before she took office, and she set about doing all she could to make matters worse. I was invited by the Workers’ Educational Association to give a talk in Consett, in County Durham, a town built around its 140-year-old steelworks. It was a lively audience, made up of men who knew where they stood, whose weekly pay packets made sure that their families were never without the basic necessities. A few days after I met them, they all learnt that they were to be thrown onto the dole. The Thatcher government had imported a Scottish American businessman named Ian MacGregor from the USA, at vast public expense, to fatten up the steel industry, ready for privatisation. The Consett steelworks made a small profit, but MacGregor decided it was not enough. In his office 200 miles to the south of Consett, he signed the death certificate of the old steelworks and threw 4,500 people out of work. The knock-on effect hit every business in Consett, where unemployment reached 36 per cent. It was a pattern repeated across the region. Factory buildings turned into empty husks, industrial estates made up of nothing but warehouses, pit villages facing dereliction, hundreds of thousands of people – men predominantly – who had been breadwinners all their adult lives 5thrown out onto the dole without a realistic prospect of ever finding paid work again. That was Thatcher’s gift to the north-east.

Most politicians try to convince the public that they are well-meaning public servants and not ruthless at all. Not Margaret Thatcher. As a woman having constantly to assert her authority over men, she cultivated her reputation as the ‘Iron Lady’, who was not for turning. She would lecture the nation on how to behave. When challenged about the north-east’s shocking level of unemployment during a rare visit to the region, she told the locals to stop being ‘moaning minnies’.

Yet in private, when not being challenged, she could be thoughtful and kind. One of the perks enjoyed by the corps of parliamentary journalists known as ‘the lobby’ was the right to dine with politicians in expensive central London restaurants and reclaim the cost. I was joined one lunchtime by Angela Rumbold, the Minister for Education, who arrived looking flustered and told us about an ordeal she had been through that morning. She had had to report personally to Thatcher on some item of policy, on which she had no doubt spent hours ensuring that she was briefed to the eyeballs and able to answer every question the boss might ask, but as she entered Thatcher’s office, she was hit by an unseen catastrophe: the minister and the Prime Minister were wearing identical dresses.

‘Did she say anything?’ I asked.

‘She did. She said, “It looks much better on you.”’

That same tactfulness was on display the first time I saw Margaret Thatcher in person. During the general election of February 1974, the Conservatives in Slough had booked a hall for a public rally, to which the press were invited. So were the voters, but, almost without 6exception, they chose to give it a miss. When three of us journalists arrived together, we almost doubled the head count. Thatcher, the Secretary of State for Education, the only woman in Edward Heath’s Cabinet, was there, accompanied by the young candidate, smartly turned out in suit and tie, looking as if he wished the floor would swallow him up. As Thatcher spotted the presence of journalists, she said in a loud voice, ‘What a lovely hall this is!’

It was a bog-standard sort of hall, and almost empty, but the humiliated candidate must have inwardly blessed her tact. Even without a public, the show had to go on. The candidate’s speech bristled with fury, supposedly directed at the Labour Party, though perhaps provoked by the absence of listeners. His best line was that a Labour government would ‘pump them and dump them’. Thatcher’s speech was delivered with good humour, as if it were a pleasure to speak to rows of unoccupied chairs. One thing I remember her saying was that she was ‘jealous’ of Sir Keith Joseph, Secretary of State for Social Services, because his department’s budget was the only one bigger than hers. Thatcher the public spending slasher was as yet unborn.

Parliament is a graveyard of ambition. So many people have gone there thinking that they could make an impact on the life of the nation and come away knowing that they have not. For some, the disappointment is so hard to bear that they have to pretend. There was an MP whom it would be cruel to name, whose body language was a symphony of self-regard, which I could not resist observing in the social setting of Parliament’s subsidised cafes. He was tall and would walk slowly, head up, rarely looking around to see who else was in the room, as if he expected all eyes to be on him. He would sit upright, elbows on the table, hands clasped together close to 7his chin. If someone to one side spoke to him, he would move his eyes to show that he was listening but would not turn his head. If he replied, he would continue looking straight ahead as he spoke. He was in Parliament for thirty years; his party was in and out of power, but no Prime Minister thought to make him a minister; no opposition leader invited him to be a shadow minister. Still, he believed he had enough political wisdom to fill a book that someone was persuaded to publish. I went to his book launch, in the hope of picking some political intelligence, and discovered I was one of just six people who turned out. Even then, he was protected by his carapace of self-importance from thinking that his long political career had amounted to nothing. I know, because when I met him later, he was good enough to tell me that he never read anything that I wrote because so many newspapers and magazines came to his office – he listed them all – but he was too busy to read them. Anyone who has time to tell you how busy they are isn’t.

Margaret Thatcher must have come up against men like that by the dozen on her rocky road to Downing Street. It surprised me, as it surprised many others, when the Conservatives chose a woman to lead them in 1975. From the Conservative councillors and office holders in the Slough area, I knew that many of them wanted to be rid of Heath and rather regretted that sending for Enoch Powell was out of the question. Sir Keith Joseph was the first to challenge Heath, but his candidature self-imploded, making way for Thatcher. I asked a Slough councillor named Mr Lawless whether the Conservatives would really countenance being led by a woman. He could be quite sardonic about the prejudices of his fellow Tories. His reply was short and blunt, ‘They’d rather have a woman than a Jew.’ 8

Something that can certainly be said for Margaret Thatcher is that she was free of antisemitism, though that was a Conservative speciality, back then. And even when she was one of the world’s most recognisable individuals, she did not walk around in a manner that exuded importance. I know, because I was almost caught out, the second time I encountered her. It was in a narrow corridor behind the Speaker’s chair in the House of Commons, a few weeks after she had won her third successive general election. It was soon after the conclusion of Prime Minister’s Questions. There was a woman in the corridor, coming in the opposite direction. It was not wide enough for us to pass each other by without risking brushing against one another. At first, I took her for a member of staff. To my surprise, she stopped and, looking amused, raised a finger and moved it in an arc, as if she were aping the movement of a windscreen wiper. It was Margaret Thatcher, giving me a choice of standing aside to the left or to the right, but making it very clear that I was the one who was going to get out of the way. There are many other people I have known who would have accompanied the gesture with an irate ‘don’t you know who I am look’, but she seemed to think it was funny that I did not immediately realise who she was.

In the summer of 1989, she came to a social event organised by lobby journalists, in a room high up in the Commons, near that part of the roof from which a fictional Prime Minister, Francis Urquhart, pushed a journalist to her death in the BBC drama House of Cards. As Thatcher arrived, she beamed with pleasure at seeing the lobby chairman, a former Daily Mail hack named Geoffrey Parkhurst, who was well plugged in to the Tory Party, and she pretended to buckle at the knees after climbing so many stairs.

In retrospect, the very fact that she was there was extraordinary. 9Other Prime Ministers have socialised with journalists but on home ground, in Downing Street, with a special adviser or two at their side to step in if difficult questions were asked. Thatcher was the last Prime Minister who would walk fearlessly into a room full of journalists, unprotected. If Bernard Ingham or another member of staff were present, they would keep a respectful distance, no doubt trying to hear what was said but not presuming to interrupt. She seemed to enjoy being surrounded by journalists, because they were too busy asking questions and trying to sniff out a story to talk down to her.

Without a spin doctor to chaperone her, Thatcher could not always know who she was talking to. These lobby receptions were open to correspondents from any recognised British news outlet, regardless of political leanings, including, for instance, the Morning Star, the Communist Party’s daily newspaper, which relied heavily on a bulk order from the Soviet Union. There could be disputes about what qualified as a news outlet. Private Eye, with its large circulation, was never allocated a lobby pass, whereas for a time, there was a recognised correspondent from the Sunday Sport, a tabloid whose front page featured such world exclusives as ‘Aliens Turned Our Son Into A Fish Finger’ or ‘Adolf Hitler Was A Woman’ or, more recently, ‘Putin Shat Himself After Two Pints of Shandy’ – until the authorities responsible for allocating lobby passes decided that this was not really a news-gathering operation.

Thatcher enjoyed herself, and stayed so long at that reception that she was still socialising when journalists started drifting. As I left, I looked back and noted that she was down to an audience of two. On one side of her was Mike Ambrose, veteran political editor of the Morning Star, and on the other, a woman who styled herself 10the ‘political editor’ of Sunday Sport. If Thatcher had let slip some government secret in that company, no one would have believed that what they wrote came from a reliable source.

One journalist she knew well and liked was the long-serving political editor of the Daily Mail, Gordon Greig. He had a career trajectory that would be impossible in the industry these days. He began as a teenage messenger on a Glasgow newspaper, did his national service, kept the regimental tie, which he would wear around the Commons to encourage old soldiers in the Conservative Party to spill their secrets, and returned to become one of the best tabloid journalists in the trade. He broke the story that Thatcher planned to challenge Edward Heath in 1975. His editor, David English, was immediately sold on the idea of a woman leading the Tories. But how, he asked, could she convince them that she was a Prime Minister in waiting when she had ‘a voice like breaking glass’? He ordered Gordon Greig to ask her that very question. It was a Sunday. It was quiet in the Daily Mail’s spacious newsroom as Greig rang Mrs Thatcher’s home. It seemed to him that everyone in the room was listening, knowing what he had been told to ask and wondering if he would. Denis Thatcher answered and called his wife to the phone. After a brief conversation, she had said enough to reassure Greig that he could write the story without risking a denial. He took a deep breath, and he asked, ‘How can you lead the Conservative Party when you have a voice like breaking glass?’

‘Breaking glass!’ she cried. The way Gordon Greig told it, it was very much like the sound of breaking glass. Thatcher took voice training later but never lost her affection for the journalist who asked her that impertinent question.

As the Prime Minister’s plane crossed the Soviet Union on its 11way back from Japan, the journalists in the party were invited to go in groups of four to talk to her in the front section, while Bernard Ingham and two other Downing Street officials stood back at a respectful distance. Thatcher made a comment about the UK’s relations with the European Union, at which Gordon Greig laughed in her face and asked, ‘Does Geoffrey Howe agree with that?’

Even I, the newest member of the party, knew the answer to that one. Two months earlier, Thatcher had elbowed Howe out of his job as Foreign Secretary because of their long-running disagreements over Europe, aggravated by personal animosity. But at that level of government, everyone must keep up the public pretence of friction-free unity, so it would have been in order for Thatcher to bat away the question with a few prepared phrases. But that was not how she reacted.

Instead of addressing the question of whether Sir Geoffrey Howe agreed with her or not, she poked Gordon Greig on the lapel and told him, ‘Rearrange your ideas, Gordon!’ Another old hand in the lobby named Frank Johnson, who, like Greig, had risen from teenage messenger boy to the top of the profession, used to say that truly serious people do not take themselves totally seriously and that Thatcher, who was well-aware of her carefully cultivated Iron Lady image, would indulge from time to time in self-parody. Watching her deal with this round of mental jousting, surrounded by men younger than her, was like being with a flirtatious granny.

People ask what it is like to meet and talk with someone who is world famous. Journalists are not very good at answering that question. Before I had ever interviewed anyone famous, I knew a journalist named David Chipp, who had interviewed Mao Zedong when he was Reuters correspondent in China. Of course, I asked 12him eagerly, ‘What was Mao like?’ and was frustrated when he could not give me a descriptive answer. The reason, of course, was that he was so focused on the task of asking the right questions and getting the answers written down in shorthand that there was no space left in his mind to be awed by the thought that ‘wow, I’m talking to Mao Zedong’.

There was a moment when speaking to Margaret Thatcher when I was suddenly, forcibly reminded who she was. As that exchange in the plane came to an end, I was the last journalist to leave and had a short one-to-one exchange with her. Talking about relations between the USA and the Soviet Union, I ventured the opinion that the new US President, George Bush (the father, not the son), knew more about world affairs than his predecessor. Thatcher did not like that. Frowning, she replied, ‘Oh, but with Ron, it all came from the heart.’ It hit me that I was talking to someone who really was on first-name terms with President Ronald Reagan.

But my greatest gasp-of-astonishment moment came after I had been trapped in a traffic jam. It was the worst traffic jam I ever experienced, not just because of how long it lasted. On the day before I was due to board the Prime Minister’s plane to Japan, I called into the Daily Mirror room in Parliament and found a yellow Post-it note on my screen from the political editor of the Press Association, Chris Moncrieff, saying that the departure time had changed. He gave a time, but I was not sure if he was telling me when the plane was leaving or when journalists were required to be at the VIP terminal in Heathrow, which was always one hour earlier. I could not find anyone who knew the answer, and in those days, no one owned a mobile phone, so as a precaution, I booked a taxi to get me there an hour earlier than Moncrieff had told me I must be there. As we 13entered the M25, the driver pointed to the fast-moving traffic and assured me we would be there in good time.

Then, suddenly, the M25 stopped being a highway and became a car park. There had been an accident ahead. We waited. At first, I could take comfort in knowing that there was at least an hour and more before the plane took off. But the traffic did not move for more than an hour and the horrible realisation descended on me that we would not be at Heathrow by the time specified on Moncrieff’s note and that, for all I knew, the Prime Minister’s plane would be up above the clouds while we were motionless below. Trapped in that traffic jam, my whole life seemed to pass before my eyes. I had something unique. I had gone directly from the Labour Party press office into a position as a political correspondent, based in the lobby. No one else has done that in the past forty years or more. I could see my future unfolding. People would laughingly repeat the tale of the press officer who landed this extraordinary job, was given the exceptional privilege of a seat on the Prime Minister’s plane, did not get to the airport on time, got sacked and never worked as a journalist again.

When at last the traffic started flowing, my nervous state had infected the driver, who got flustered as I was giving him directions to the VIP terminal and took a wrong turn. Finally, we were at the gate, and a police officer came to the window to check who we were. Had Mrs Thatcher’s plane taken off? I asked, dreading his reply. No, he said, her car was forty minutes away.

I floated into the VIP lounge on waves of relief, not caring when a Downing Street official pointed out that I was late and told me to go add my passport to the others, which had been collected and placed in an adjoining room. There I saw that they were in two piles. I did 14not know to which I was supposed to add mine, so I picked up the top one from a pile, flicked it open and discovered to my amazement that I was holding Margaret Thatcher’s passport. I could not have been more astonished if I had been holding an artefact from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

I wonder what would have happened if the civil service had forgotten to pack her passport, or a sneak thief had stolen it to keep as a memento, and she had arrived abroad without it. Would an immigration official have refused her entry? I resisted the temptation to steal Margaret Thatcher’s passport and quickly put it back where I had found it.

2

Surviving Childhood

The closest vote in Parliament during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership was on 22 July 1986 when the Commons decided by 231 to 230 to ban corporal punishment in state schools. The Labour government later extended that law to private schools. But when I was growing up in the 1950s, young children were expected to be sturdy. Beating them, at home or at school, was thought to do them good.

The risks that parents took in the post-war period, ignoring dangers in the home or on the roads, would in our time warrant a visit from social services. I believe my mother was more alert than most to the possibility that something bad might happen to her brood. As she came to collect her sons from nursery school on 6 February 1952, she saw a group of mothers standing outside with shocked and solemn expressions and immediately felt a stab of cold fear that there had been an accident involving the children. A mother stepped towards her and asked in a hushed tone whether she had heard the news. 16

‘The king has died,’ she announced sombrely.

My mother tried to hide her relief. ‘I was sorry about the king but so glad nothing had happened to either of you,’ she told us later.

And yet my earliest memory is from the age of two, of playing near an unguarded free-standing electric heater, whose bars were glowing red, in the children’s bedroom in our home in Thames Ditton. My parents used to call it the ‘electric fire’, but to me it was a disappointing ‘fire’, not like the exciting one that burned in the hearth in the sitting room, with its fascinating tongues of dancing orange flame. I did not know the word for flame, but I remember wondering whether this so-called fire contained any of ‘those things’. As a test, I draped a towel nappy over it and very suddenly discovered that – yes – you can draw flames out from an ‘electric fire’. The cries of alarm brought my parents hurrying into the room. I remember them standing in the doorway, after my brother and I had taken refuge on the side of the bed farthest from the door. The nappy lay smouldering on the green linoleum floor.

It seems shocking now that parents would allow two very small boys to play unsupervised near an unguarded electric heater, but that generation had been through the Blitz and the V-1 and V-2 rockets. My father had survived German bombardment in north Africa. My mother had seen what a bomb could do while she was a volunteer fire warden. Those dangers had passed. This was peace time, a time of austerity and rations, when a mother’s primary concern was how to make sure there was food on the table. This was no time to start worrying about hazards in the home or on the roads.

I was aged either four or five when I was told that I could go out and play with a friend who lived nearby. I set off alone, dressed in a new pair of green dungarees. I had not gone far before my 17dungarees had turned into a suit of armour as worn by the Knights of the Round Table, and I was invincible. As I crossed a road, I saw a car coming and deliberately stopped and stood in its path, knowing that a vehicle could not so much as dent my dungarees. The driver braked and sounded his horn. The noise sent me scuttling to the pavement.

That shock did not put me off cars at all. One of my fondest childhood family memories is of my father’s old Chevrolet. It had only two seats, but when the boot lid was down, it revealed a small bench which could hold another two passengers, facing backwards. Thus we would set off on family outings with my parents in the car and my brother and I on this bench, with only fresh air between us and the tarmac. If that Chevy had lurched forwards suddenly… but then again, I doubt that it had the horsepower to do anything suddenly.

When I was eight, I was sent to a boarding school called Wells Court, near Tewkesbury, where we were encouraged to climb the tall trees in the school grounds as high as we dared, a policy that remained in place even after one nine-year-old fell and broke his leg. I witnessed him being carried back into the building in tears. We were also allowed to own sheaf knives with four- or six-inch blades. I pestered my mother to buy one for me. Reluctantly, she did but arranged for her father, who was a builder, to blunt the blade. To my shame and embarrassment, I was the only boy in school whose sheaf knife was not sharp enough to cut anything.

There were a small number of day-boys whose families lived close to Wells Court, who would come in for lessons and go home in the evenings. We despised them, because they did not have to endure what we endured, so they formed their own little gang, whose acknowledged leader, in my time, was a boy named Phillips. 18My best friend and I spotted Phillips in a field on his parents’ farm as we were returning from a walk one Sunday afternoon. We were having a mock argument, and I thought up a great joke: I told my friend that I was going to send Phillips to beat him up – there being no one and nothing so unthreatening as a day-boy. I was surprised when, fifteen years later, for the first and only time in my life, a letter arrived by post from Wells Court, containing the breathless news that the former day-boy Mark Phillips was to marry Princess Anne.

Wells Court was the junior branch of a school for ten- to thirteen-year-olds called Wells House, located in the beauty of the Malvern Hills, where Edward Elgar taught music. Both establishments were run by a character named Alan Darvall, who liked to be known as ‘Beak’, who took charge of Wells House in 1933, ran it for thirty-five years and would have thought it most odd if anyone had suggested to him that he could keep order without resorting to the riding crop. He is commemorated in the memoir Under a Mackerel Sky by the celebrity chef Rick Stein. I remember Christopher Stein, as he then was – a cheerful, rotund redhead who did not stand out as a future high achiever but seemed content to drift along, doing OK and enjoying himself, although he was obviously more knowledgeable than the average child. When I was eight years old, I walked into a classroom where two older boys were joking, one of whom I presume was called Francis, because the other turned to me and announced, without preamble, ‘We’re Frankenstein – he’s Frank, I’m Stein.’ I had, at least, heard the name ‘Frankenstein’. Some years later, an older boy pointed to a friend and informed me, ‘I’m Toscanini; he’s Paganini’ – and unless my memory is wrong, that also was Christopher Stein. He must have heard adults at home mention 19those two names and been amused by their similarity. I had certainly not heard of either.

There was no malice in Stein, but there is a passage in his memoir that I did not like, in which he recalled hearing adults describe Alan Darvall as ‘a silly old histrionic queen’, and he wrote that ‘Beak was unmarried and we were all a little scared of him. He was keen on beating us regularly. I managed to avoid it generally, but others were not so fortunate.’ In the book, Stein added, ‘Beak never touched or spoke to any of us inappropriately and was a thoroughly good headmaster’ – but I do not remember reading that in the excerpt published in the Daily Mail.

I do not doubt that Beak was gay, but his sexuality was never relevant and he was never inappropriate with the boys in his charge. He did, though, make regular use of corporal punishment, but it was never my impression that he was ‘keen’ to beat. He was a religious man who knew his Bible, with its adage that ‘he that spareth his rod hateth his son’, and would have thought it strange if someone had suggested that it is not necessary or desirable to beat young children.

There was one occasion I remember well when he really did not want to wield the riding crop but duty called. Once a term, on ‘Expedition Day’, the entire school was sent out on long supervised walks across the Malvern Hills and came back, supposedly, tired out and ready for sleep. On the evening of Expedition Day in the winter of 1960, I was cleaning my teeth in a communal bathroom, when I spotted an unusually large tube of bright pink toothpaste, an unfamiliar brand, possibly belonging to a child whose parents were stationed abroad. It seemed perfect for a prank. I stole it, removed 20the cap, placed the tube in the bed of a boy with whom I shared a dormitory, named Philip, and persuaded the other inmates to jump on their beds. When Philip returned from the bathroom, I told him that we were having a competition to see who could jump highest. He, of course, joined in with gusto, oblivious to the fat, open tube of toothpaste beneath his feet. After lights out, his cries of surprise and protest were heard by a member of staff, and Philip and I were sent downstairs in dressing gowns and slippers to explain to Beak why there were pink smudges all over his pyjamas and a lump of pink toothpaste in his wiry hair. I took full responsibility. Beak was tired out by the long day’s tramping over the hills and really did not want to put himself through the exertion of delivering a beating, no matter how richly deserved. ‘This is a terrible ending to Expedition Day,’ he exclaimed, with self-pity in his voice. He was still complaining over breakfast the following morning.

Though Philip had been ordered to go straight back to bed while I was dealt with, he bravely waited on the staircase to check that I was all right – which makes me sorry to recall that later he became the target of systematic bullying, in which I took part. There were nine of us in the sixth form in our last year. We would see one another six or seven days a week during three long terms and, being sixth-formers, we mostly kept to ourselves. Within this enclosure of swirling friendships and animosities, there was an inbuilt risk that someone would get victimised. Philip had mildly eccentric ways; he was not good at sport, strove very hard to please the teachers and did not know how to gang up on anyone, and he became the constant butt of taunts and cruel jokes. Someone composed a song that mocked his physical appearance and friendlessness. One of the 21teachers knew he was being victimised and tried to put a stop to it, but he resorted to shouting and issuing threats of punishment, which only hardened hostility to the victim. I believe that I might have responded if an adult had taken me aside to say that what we were doing was cruel and distressing, because there were moments when I half wanted to be friends with him again, but they soon passed. It was safer and more fun to go with the crowd. The only excuse I can offer is that I was twelve years old. I have no memory of ever being implicated in bullying during my teens.

Meanwhile fourteen miles away at Wells Court, where the boys were younger, there was a headmaster who was not a bachelor or ‘histrionic queen’ but married to an elegant, softly spoken woman, much loved by the pupils, and with a son my age. This family man did something that Beak would never do: he would deal with particularly bad breaches of discipline by making a child pull down his trousers and pants to receive a beating on bare skin. During one communal bath time, he stood at the door, watching and waiting, until a boy named W stepped out of the bath, whereupon he was ordered to proceed to an adjoining room, naked and dripping wet. He reported that a leather strap on wet skin stung worse than a bed of nettles. These beatings were, of course, a regular topic of conversation. I can recall one meal where a boy, who would have been aged nine, made a joke too obscene to be reproduced in print.

Yet he too was a good and kindly headmaster, with a lively sense of humour. He would joke about the beatings he administered, saying that it turned boys into ‘striped tigers’, which made us laugh. It is wrong to suppose that only sadists or fanatics used to beat young children. The uncomfortable truth was that caring teachers did it, 22believing without question that it was good for a child’s character – and in so doing, they provided cover for others who were not so well intentioned.

One day, when I was twelve or thirteen, I could not help but notice that one of my friends at Wells House had a swelling on his forehead almost the size of half a golf ball. A junior teacher had lost control and hit another boy during class. My friend objected, saying that if the master were to hit him, he would complain to Beak, so the master did just that, with the kind of force that could have concussed a child, then dared him to complain. He took heed and said nothing.

Other teachers would hit the children without fear of being called to account. There was a former colonel at Wells Court who made us address him by his old army rank, who would call a child to the front of the class to be publicly slapped on the back of the leg, so hard that it usually drew tears. There was another who taught mathematics and sport and liked boys who excelled on the sports field but struggled in class. I was the cleverest in the maths class, and hopeless on the rugby pitch, so he really did not like me. We were cleaning up in the washroom when I accidentally spilled paint on another boy, which threw the teacher into a rage. He forced me down over the basin and delivered a vigorous kick on the arse. I did not howl or cry, which only angered him the more. He delivered a second kick. Still no reaction. There he stopped. Perhaps it crossed his mind that injuring me might harm his career.

He had a special favourite, named Richard, whom I thought of as being a reincarnation of Richard III, because he was a bully, but he had the dual virtues of being stupid and good at sport. One evening, that teacher, who had a bachelor’s bedroom next to one of the boys’ 23dormitories, heard Richard’s voice, talking after lights out. The correct procedure would have been to report the offence to the headmaster, but instead he marched his pet pupil into his bedroom, to chastise him with a cricket stump. In that school, where the oldest pupils were aged ten, and none of us knew anything about adult sexuality, we instinctively understood as the story went around the school that he had acted in that strange way precisely because Richard was his special favourite.

Wells House had a deputy headmaster, Mr Hall, known as ‘Stubbs’, who claimed that he had killed a German soldier in face-to-face combat during the war. When Beak was absent, or when he pleaded that a sprained shoulder or some other ailment prevented him carrying out the duty of beating, he would hand the responsibility over to Stubbs, who claimed to dislike performing this delegated task; I can remember him telling us that we were wrong to picture him ‘grinning behind his cane’. But it was revealing that he felt he had to issue a denial and in such vivid language. Stubbs was short but very powerfully built, and his beatings were greatly feared.

Stubbs ran the school for one whole term while Beak was away and discovered that maintaining discipline was not as easy as it seemed. One Sunday, the whole school was supposed to have walked to a specified destination and back, but the majority decided not to bother going the full distance. All the culprits were ordered to own up and present themselves outside the headmaster’s study. Dozens joined the line, with a shame-faced prefect at the front. Stubbs marched angrily along this long queue, spotted one boy laughing and lost his temper. He ordered the child into the study for a beating. Those of us in the long queue heard each blow as it hit its target. The sound of human flesh being struck with a cane can be 24sickeningly loud. I can still picture that child on his way out, staggering past the long line of his fellow pupils, rubbing his behind, in tears, in pain and publicly humiliated, because he had picked the wrong moment to laugh.

Rick Stein mentioned a feature of Wells House life, that on sunny summer days, we would congregate in the school’s outdoor swimming pool, to swim naked, watched over by male staff. This was not as sinister as it may sound, but it meant that any boy who had been beaten in the previous few days would necessarily be displaying the evidence. There was a boy, call him A, who was so unhappy at that school that he made one attempt to run away. At other times, he shielded his happiness behind flippancy, answering every comment directed at him with what sounded like an attempt to make a joke. This habit greatly annoyed Stubbs. When given the opportunity to beat A, he set about it with a vigour that would have had any child screaming in pain. Afterwards, A was obliged to join us for a swimming session. He had wrapped a towel around himself but drew a curious crowd of boys pleading to be able to see whether the beating had really been as severe as was rumoured. With that unhappy smile that was almost always on his face, he reluctantly removed the towel and turned about to display a riotous tapestry of scarlet, black, yellow and blue welts and bruises, which drew cries of wonder and admiration. We had never seen a boy’s bum so richly decorated. If Beak had been in charge, he would have put a stop to this show, but Stubbs said nothing. Silently approaching, hands in pockets, he too took a close-up look. I did not have much respect for him. Above the surrounding noise, I exclaimed, ‘Aren’t they lovely, sir?’ He walked away slowly, hands deep in his pockets.

This was a school for privileged boys whose parents were paying 25for their education and knew what was happening but thought it normal and correct. It was excellent cover for the truly sadistic abuse that was taking place in homes for children in care, who had no protection. Fathers tolerated their sons being beaten because they had been beaten when they were boys. A cliché of that time was the adult who proclaimed, ‘It never did me any harm.’ Some children were terrified by the prospect of a beating, but most treated it as a rite of passage, like having to start the day with a cold bath. ‘Did you blub?’ was a common question addressed to the victim. He gained kudos if he had emerged dry-eyed. Some boys even boasted that it did not really hurt, it just stung a bit. I heard this from older boys when I first arrived at Wells Court, so when a fellow new boy had been the first of our intake to undergo this experience, I asked if it was true that it did not hurt, it only stung. The child, who was eight, did not know the correct reply and exclaimed truthfully, ‘It hurt a jolly lot!’

It took decades to turn public opinion against beating children. Two cultural landmarks of 1968 were the publication, for the first time, of the unexpurgated text of George Orwell’s memoir of his time at a preparatory school called St Cyprian’s, Such, Such Were the Joys, and the cult film If…, directed by Lindsay Anderson, which included a depiction of a sadistic beating inflicted by prefects. It was filmed in Cheltenham boys’ college, Anderson’s old school, where I was also a pupil, so I should add that beatings at Cheltenham were very rare and never carried out by prefects. In 1984, Roald Dahl pitched in with a grim and bitter memoir of his school days.

I was working on The Journal, in Newcastle, in 1976, when parents objected after two teenage girls were beaten by the headmaster of a local comprehensive school, as the law allowed. The future Tory 26MP Piers Merchant was a fellow reporter, known for his off-colour humour. He remarked, ‘If I’d known that it gave me the right to beat little girls on their bottoms, I’d have taken up teaching.’

He was joking, but he illuminated a truth. It was not just the pain involved that made this practice obnoxious; what was every bit as sinister was the pleasure some people found in doing it.

3

The End of Piers

There is a cliché that all political careers end in failure, but not many fail as spectacularly as that of my aforementioned colleague, Piers Merchant. Now that his name has cropped up, I will complete his story.

I did not take to him when I first saw him across the open-plan newsroom at The Journal, in Newcastle upon Tyne, when he was twenty-four, the youngest journalist on the subs’ table. He was keen, alert and anxious to please the editor and anyone else in authority. There had been a journalists’ strike at my previous newspaper, in Slough, so well supported that the editor was going to have to produce a newspaper single-handed, until to his surprise, one subeditor, a member of the National Union of Journalists, crossed a picket line to join him. Piers had a tight, thin, pointed face, just like that sub’s. I guessed that if there were ever an NUJ strike at The Journal, he would break it.

I was wrong. There was a strike after I left, and Piers did not merely support it, he led it, as Father of the NUJ Chapel. Leading 28a strike can be a gamble. The union representative might be swept away in the next round of redundancies, or his skills as a leader and negotiator might make such a big impression that he is promoted. Piers advanced quickly from strike leader to news editor.

I liked him once I came to know him. I had an unusual reason for being very grateful to him. My twenty-eighth birthday had sent me into a spiral of gloom. Twenty-eight seemed old, too old ever to advance onto a national newspaper. I feared that I was trapped in provincial journalism for life. Living alone in a single rented room, I went through long nights of sleeplessness, mornings when lead weights seemed to hold me in bed, days permeated with a feeling of failure. I struggled to keep working as normal in the office, where no one seemed to notice that anything was wrong, except Piers, who took one look as I was walking past the subs’ desk, exclaimed that I looked terrible and asked what was the matter. I lied. I said that I was fine, but I never forgot that moment of observant kindness.

We discovered a shared interest in politics. During long conversations, the opinions he expressed were tolerant and middle of the road. When the Social Democratic Party was launched a few years later, it struck me as being the place for people like Piers. By then, I had been out of touch with him for a while and did not know that he was an active Conservative. At certain times in his political career, he talked the talk of an English nationalist and borderline racist, yet I do not believe he was either. I think, fundamentally, he was frivolous. There are people who think that politics is all a game. Piers was one of them. That was his undoing.

He had terrible judgement, which took him across the thin border between edgy humour into bad taste, or worse. He liked to pretend to be a Gestapo officer and would conduct mock investigations into 29his fellow reporters on The Journal, always concluding that they were subversives who should be shot. One Christmas, during an office pantomime, he announced, in a mock German accent, ‘You know I haff vays of making you laugh: I just haven’t found them yet.’ While he was a reporter, most of his peer group found his humour amusing, if peculiar. It was not funny when he was news editor. One evening, he forgot to lock the filing cabinet reserved for his personal use, and journalists on the night shift discovered personal files Piers kept on his staff. One was described as ‘manic depressive’, another as a ‘plagiarist’. The municipal correspondent, Bryan Christie, was said to be unable to ‘dig for stories’ – in recognition of which, when he left soon afterwards, his colleagues presented him with a garden spade. The worst discovery, by far, was a cartoon Piers had drawn of himself as a Nazi concentration camp guard watching as his staff were marched into a gas chamber. One of them had Polish antecedents. Two were Jews.

During the 1983 general election, I volunteered to act as press officer for the Labour Party in the marginal seat of Newcastle Central. The Labour candidate was a lifelong friend named Nigel Todd, a Newcastle councillor whose daughter, Selina Todd, achieved eminence as a historian, academic, writer, socialist and feminist, and who was targeted by trans activists months before J. K. Rowling entered that bear pit. The Conservative candidate was, by coincidence, Piers Merchant. It was a bonus for the Tories to have this media-savvy candidate, who had once led a strike, in a region where unions were strong and Conservatives were thin on the ground. But while the election was under way, someone turned up an old piece of campaign literature, dating from 1970, when an ultra right-wing fringe party had contested a seat in Piers’s home 30town of Nottingham. By law, election leaflets have to bear the name and address of the election agent. The name on this tatty leaflet was P. R. G. Merchant; the address was his parents’ home.

The possibility that he had had links with the far right was investigated thoroughly, without turning up any evidence, apart from that old leaflet. He flatly denied knowing how his name came to be on it. The connection appears to have been through Air Vice-Marshal Don Bennett, a man with a very fine war record and a very dubious penchant for supporting far-right fringe groups. Piers had met him while he was a student at Durham University and, having more curiosity than judgement, must have let himself be drawn in to something he should have avoided. In a normal year, the mere suspicion of a link to the far right could have ended his chances of ever entering Parliament, but this was 1983, when Labour was losing seats to the Conservatives like never before, and he was elected.

His four years on the back benches were spent in semi-obscurity, except for one occasion when he made the national news, by mistake. He was interviewed by a local television station in September 1985 and made a few unexceptional comments about the level of unemployment in the north-east. By sheer mischance, this was the day when Margaret Thatcher paid a rare visit to the region, and when challenged about the rising jobless figures, she retorted sharply that the way to attract investment to the region was by ‘not always standing there as moaning minnies. Now stop it!’ Inevitably, the bulletins cut away from her to Piers Merchant’s conciliatory platitudes, making it appear that he was deliberately contradicting his leader, which he never intended. In those few minutes, his chances of being a minister in her government went down the plug hole.

After losing Newcastle Central in 1987, he made a comeback 31in 1992 as MP for Beckenham, a solidly safe Tory seat in south London, which, with a little more care, he could have held for the rest of his life. I was glad to see him back in the Commons, because I was short of contacts in the Tory Party and Piers loved to gossip. He never achieved any office higher than being an unpaid parliamentary private secretary to a middle-ranking minister – but just as it was all over for the Conservative government, he rocketed to fame.

Apparently, the first hint of danger came at a rally addressed by Piers Merchant and Eric Forth, Tory MPs from neighbouring south London constituencies. A young woman in a short skirt was in the front row, giving them admiring looks. Afterwards, Forth remarked to his fellow MP, ‘That woman is trouble!’

Generally, a highly sexed, adolescent woman is ‘trouble’ for a middle-aged man only if he actively wants to be troubled, which Piers evidently did. As the 1997 general election was in full flow, The Sun ran six pages of photographs of him with this seventeen-year-old ‘nightclub hostess’ in a park, in his constituency, in the midst of the campaign, looking for all the world as if he was enjoying fellatio in the fresh air.

For the rest of his life, Piers asserted that the camera lied, that he and the teenager were only being affectionate and that The Sun had paid her to entrap him. I think he was telling the truth. It was obviously a set-up: tabloid photographers do not randomly lurk in bushes in public parks hoping to capture MPs having rumpy-pumpy out in the open with campaign volunteers. There is no reason to doubt that the young woman was bribed by The Sun to simulate sex, but it is not plausible that she would risk arrest by actually performing a sexual act, knowing there was a camera nearby. Even so, Piers’s behaviour was staggeringly foolish. For 32months, ever since John Major had launched an unfortunate campaign slogan ‘Back to Basics’, which, according to the accompanying spin, was to include an emphasis on sexual morality, the tabloids had delighted in exposing the extra-marital goings-on of Tory MPs. The Piers story was a classic of that genre: a Tory MP seemingly so horny that he could not resist having sex with a teenager in a public place in his constituency in mid-election. ‘What on earth does he think he’s doing?’ is the reaction that John Major recorded in his memoirs, where he added that ‘a few million other Britons, over their breakfast newspapers, must have been spluttering in similar vein’.