8,06 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

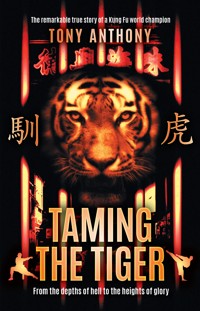

TONY ANTHONY knew no fear. Three-times World Kung Fu Champion, he was self-assured, powerful and at the pinnacle of his art. An extraordinary career awaited him. Working in the higher echelons of close protection security, he travelled the globe, guarding some of the world’s wealthiest, most powerful, and influential people.

This fast paced, compelling and, at times, chilling account is Tony’s deeply moving true story. More extraordinary than fantasy, more remarkable than fiction, this blockbusting read almost defies belief. With fascinating insight into China’s martial arts, and the knife-edge adrenaline highs of the bodyguard lifestyle, it documents the personal tragedy that turned a ‘disciple of enlightenment’ into a bloodthirsty, violent man.

From the depths of hell in Cyprus’s notorious Nicosia Central Prison, all might have been lost, but for the visits of a stranger.

Translated into 40 languages and more than 2 million copies sold worldwide.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Taming the Tiger

Revised Edition

From the depths of hell to the heights of glory

The remarkable true story of a Kung Fu world champion

tony anthony

Copyright © 2022 Tony Anthony

Published by

Great Commission Society

Summit House, 4-5 Mitchell Street

Edinburgh EH6 7BD

www.greatcommissionsociety.com

First published by Authentic Media in 2004

Revised edition published by New Wine Press

RoperPenberthy Publishing Ltd in 2015

The right of Tony Anthony to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library

ISBN: 978-1-7396976-1-7

Unless otherwise stated all Scripture quotations are taken from the

HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION.

Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica. Used by permission of

Hodder & Stoughton Publishers, a member of the Hachette Livre

UK Group. All rights reserved. ‘NIV’ is a registered trademark of

Bliblica UK trademark number 1448790.

DISCLAIMER

This book tells the true story of Tony Anthony. Some scenes have been dramatized with

authentic, though not necessarily actual, dialogue and detail. In addition, to protect

the author, his family, and the rights of those whose paths he has crossed, the names

of some characters, companies and places in this ebook have been changed.

Cover design by Jay Thompson

Printed and bound in Great Britain by UK Book Publishing

www.ukbookpublishing.com

Dedication

I dedicate this book to Michael, who called out to me in the wildernessand continues to call out to others.

And to my best friend Sara, for being a godly, gorgeous, excellent wife and mother.

‘Taming the tiger, defeating the dragon’(Chinese proverb)

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge with great thanks all those who have made this book possible.

The original publication of my story would not have been possible without the tenacious devotion of my writer, Angela Little who pieced together the entire narrative. Thank you for understanding the person I was and the person I have become.

Special thanks to Malcolm Down from Authentic Media for publishing the first edition of Taming the Tiger, and to Richard Roper from New Wine Press for publishing the first revised edition of my testimony.

I would also like to thank Ian Bruce, Laura Barnett, Robert Quay, and the late Mei Lee, and so many other friends around the world who read the manuscript or helped with research and administrative support. And to the many friends whose lives interfaced with mine on this amazing journey but who are too many to mention. You are appreciated, nonetheless.

Most of all, I would like to thank my wife, Sara. She is my best friend, devoted encourager, and most trusted critic. She always brings balance and wisdom with a smile, to a deeply satisfying, yet sometimes emotionally draining ministry. To my sons Ethan and Jacob, who say, ‘Dad, we really miss you when you are not here,’ and who remind me when I come home from mission that my job as a dad is to nurture their ability to dream big and help them pursue their dreams.

Lastly, to you the reader. Thank you for taking the time to read my story.

Tony Anthony

Chapter 1

Shane D’Souza was barely recognisable. The guards scraped him off the cell floor and laid his mangled body on a dirty stretcher. He had been beaten, battered, cut, raped, and ruined in every way. Pools of blood formed great purple patches on cold concrete. The trail of mutilation snaked its way down the dark corridor as they carried him off to the hospital wing. The small gathering of men shuffled away. We all knew who was guilty of the assault on the young Sri Lankan. No one said a word. The authorities didn’t care. There’d be one less con – fylakismenos they called us – on B-wing. Another would soon take his place. There’d be no inquiry, no punishment for the attacker. No justice for my friend.

It was just another day in Nicosia Central Prison. We were murderers, drug pushers and smugglers, gangsters, child abusers, thieves, rapists, terrorists and fraudsters: a miserable mixed bag of human depravity; the meanest of the mean and the downright unlucky, tossed together in a stinking hot-pot of a Cypriot jail.

There were many rules, but they weren’t the ones laid down by the authorities. We each lived by a code of violence, necessary for self-preservation. You always had to watch your back. It was every man for himself, and blood was often spilled for little more than recreation. Still, there was something of an alliance between Shane and me. When I saw what had happened, it triggered a dark and dangerous rage inside me.

A number of the most violent inmates in the prison were nicknamed Al Capone or ‘Alcaponey’. The particular Alcaponey who had brutally attacked my friend was an unpleasant piece of work. No one knew his real name. He was one of the mentally deranged; the criminally insane. The courts didn’t bother with asylums; they just imprisoned their madmen with the rest of us. They were a law unto themselves. Alcaponey was one of the worst. A barbaric Cypriot, he was a loner who barely spoke his own language. Serving time for murder and multiple rape, he was a grade one psychopath. Whilst the rest of us occupied our time with drug use, petty theft (primarily cigarettes and chocolate, which were the main form of currency) and occasional arts and crafts, Alcaponey spent his days mutilating and raping other inmates. He was a lifer on a mission to make a living hell for the rest of us.

On the day Shane was brutalised, I vowed to take vengeance on him. Alcaponey was a good foot taller than me. He pushed weights and his arms were as thick as my thighs, but I knew I could have him. I knew I could kill him with my bare hands and make him suffer for every blow, every stinking sordid deed, every drop of Shane’s blood.

In the days ahead, a hushed anticipation hung over the jail. Everyone knew I was after Alcaponey. It wouldn’t be pretty. I was just waiting for my moment. Almost two weeks passed and with each day I grew more angry and more determined to make him suffer. It wasn’t enough to kill him. I’d make him beg for mercy, before releasing him to his devils. I was a world class Kung Fu champion, with the skill to burst him open and break him into a million pieces. I could do it easily with my bare hands, but these days I often carried a blade. Most men did. We broke them out from our razors and hid them under our tongues or some other place where they could not be easily detected. It wasn’t as though the guards bothered much. Some of them took sadistic pleasure out of it. Others just turned a blind eye. What did they care if an inmate got cut up or raped with a blade to his throat?

Gammodi bastardos! Suddenly, I was slammed against the wall as Alcaponey’s screech echoed round the dark, desolate corridor. I was angry at myself for being caught off guard, but adrenaline raced through my veins. At last, my time with the demon had finally come.

The stench of his breath was sickening as he leaned the full weight of his huge body against me, pushing his nose to mine. A blade dug sharply at my neck, waiting to slice my jugular. Immediately, I grabbed his greasy face with my free left hand, my thumb over his eye socket, ready to puncture. We grappled with each other as I quickly calculated my moves. I knew I would receive a life-threatening cut, but that didn’t matter. Nothing mattered any more. I might die, but I would kill him first.

I wanted his blood. I’d easily take his eye before ripping off his ear with my teeth. Fury boiled within me, but suddenly there was something else. In the heat of those split seconds I was strangely aware of a much deeper battle raging. It had little to do with Alcaponey. This one was all mine. It was as though some kind of new consciousness was weakening the ingrained instincts that made me the combat fighter I was. As I fought to focus my attention on Alcaponey’s ear, I had an image in my head from something I had read only that morning. A man unjustly arrested and his friend defending him, cutting off the ear of the servant of his accuser. Alcaponey’s ear was just inches from my mouth. ‘Come on Tony, just bite. You’re fast, you can take it,’ the voice of my instinct spoke. ‘No, wait … all who draw the sword, die by the sword …’

Where did that come from? ‘Come on boy, just do it! What are you waiting for?’ As the conflict raged within me, I felt Alcaponey’s free hand grasping down at my groin. His evil grin bared broken, rotten teeth as my fingers dug into his face, stretching, and tearing at the leathery skin. There was the voice again. ‘Come on, are you going to let yourself be cut and raped like Shane?’

What was stopping me? I didn’t know. I kept a tight grip on the brute, as his body locked me against the wall, but something was preventing me from making my next move. In the brief moment it took for a drop of sweat to roll down Alcaponey’s face, the two voices of my inner being fought with each other. As one voice, then the other struggled for supremacy, to me, it seemed like an eternity. It was a debate that addressed a whole lifetime and challenged the very core of who I was – who I had become.

I knew which voice had to win. But what then? Could I allow myself to be mutilated, just like my friend? Or could I really trust this new consciousness, this new voice that seemed so determined – so sure? Suddenly, words came out of my mouth. They were calm, clear, authoritative. Alcaponey knew only Greek, but in the surrealism of the moment, I spoke English. As I said the words, I released my hold and waited.

In the next split second I felt the weight of shock run through Alcaponey’s body. He shivered and goose bumps rose on his clammy skin. His murky eyes glared in terror, and I braced myself for the assault. Suddenly, my body heaved as he loosened his grip. We stood, still inches apart, glaring at one another’s faces. Then, in a moment, he turned and fled. He was like a man possessed, running with his hands shielding his head. His blood curdling scream bounced off the concrete walls as I watched him disappear into the darkness.

I put my hand to my neck and peeled the thin blade from my skin. It hadn’t left a mark.

Chapter 2

It was in 1975, when I was only four years old, when my life took a sudden turn for the unexpected. I was living with my parents in London at the time. Hardly anyone ever came to our house, so when the doorbell rang one day, I stood excitedly at the top of the stairs, trying to catch a glimpse of the visitor. My father opened the door and a man I had never seen before was ushered through into the living room. The stranger was Chinese, like my mother. I crept down to take a peek through the half-open door. They were talking in such low voices I couldn’t make out what they were saying. From my hiding place, I could see the stranger’s face. It was mean looking.

‘Come in Tony.’ Mum’s voice startled me. Being careful not to look directly at the man, I pushed quickly passed him and tried to hide behind my father’s legs. Mum reached out and pulled me to her. I didn’t know what to do. I looked to Dad, but he just stared at the fireplace. He was blinking heavily, as though he had something stuck in his eye.

Suddenly, the stranger took me by the wrist. Flinching, I tried to pull away, but he held me tightly and Mum gave me that look – the one she used when I was to be quiet. She handed the stranger a small bag and, almost before I knew it, we were outside, walking down our garden path, leaving my parents behind.

I don’t remember much about the journey. The stranger said nothing to me. I had no idea where he was taking me. When I found myself at the airport I began to tingle with a mixture of excitement and fear. This might be a fantastic adventure, but no, something was wrong, really wrong. The stranger still did not speak as we started to board a plane. As time passed, I grew more and more fearful. It seemed the flight was never going to end. Surely Mum and Dad would come soon? We’d go back to the house. Everything would be alright. Little did I know, I was on a plane bound for China. A child with a new name and forged documents; a people devastated by a decade of violence; a land with broken borders through which a small boy could pass unnoticed. My life was being changed forever.

At four years old I couldn’t have understood the complexities of my parents’ lives. What I did know however, was that my mother hated me. Sitting on the plane, all I could think about was how angry she was with me. What had I done this time? I knew I had ruined my mother’s life. She told me so. She was always angry.

Some time before the stranger came there was an incident I have never forgotten. We had moved from our little West End flat into a big house in Edgware, north-west London. To me it seemed huge and I remember squealing excitedly, running from one room to another. Mum and Dad bought a big new bed and I was bouncing on it, throwing myself face first into the soft new duvet. Suddenly Mum came storming in. ‘Stop that immediately, you stupid child!’ she yelled, dealing me a harsh slap across my legs. Moving over to the dressing table, she picked up the large hand mirror and started to look at herself, jutting out her chin, poking her lips and preening her eyelashes in the way she always did. I scrambled to get off the bed quickly but, in my haste, missed my footing and came bouncing down into the quilt once more. I couldn’t help but let out a gasp of laughter.

Before I knew it, she was upon me. There was a crashing noise above my head followed by an almighty crack and my mother’s angry voice…, shrill, swearing and cursing at me. My head swam with sudden, intense pain.

‘You idiot child, what did I tell you?’ she was screaming in a frenzy. ‘Now look at you!’

She marched out of the room slamming the door behind her. Somehow, I couldn’t move. The frame of the mirror stuck tight over my shoulders and pointed shards of broken glass were cutting into my neck and face. There was blood too, and more came as I winced in agony, willing myself to pull a sharp edge away from my cheek.

I awoke with a start and realised we were getting off the plane. Where were we? I tried to rub my eyes, but the stranger still held my wrist. I wanted to cry. There was a lot of chatter, but I couldn’t understand any of it. People were shouting, but their voices were high-pitched and unintelligible. Fear and confusion swept over me. Who was this man? Where had he brought me? People scurried around with bags, trolleys, and parcels, but it wasn’t like the airport we had been in at the beginning of the journey. The air was thick with cigarette smoke and other strange smells. Overwhelmed with drowsiness, I began to cry, in big, breathless sobs. ‘Sshh!’ hissed the stranger, sharply tightening his grip so I felt his fingernails in my flesh. My wailing was quickly suppressed in pain and silent terror. He tugged again, this time pulling me out into the evening air. Of course, I didn’t really understand that I was in China, let alone that the country was still in the final stages of Mao Zedong’s brutal and chaotic Cultural Revolution; but one thing I did realise as we left the airport was that I was far, very far, from my home, my parents and everything I had known before.

Like a frightened rabbit, I scanned the scene, hoping to catch sight of my mother or father. The people wore strange clothes. There was a lot of shouting, several dogs were barking, and I noticed a man holding a cage which had birds in it. We stopped. Before me stood a spindly man dressed in a silky black jacket with wide, loose sleeves and a high collar. Only in very recent years have I come to discover the identity of this man. His name was Cheung Ling Soo. As a child I was led to believe he was my grandfather, though the truth lies in a tangled web of deceit, shame and ambition. Cheung Ling Soo was a contemporary of my maternal grandparents. A revered Grandmaster in Kung Fu, he was wealthy and influential and a betrothal to my mother was set to secure the future of the family at a time of great turmoil for the Chinese community. My mother however, had a will of her own. Her parents had escaped civil war in China and she had been born and raised in Great Britain. She had no desire to return to the ancestral home – then in the throes of the Cultural Revolution – in an arranged marriage to a much older man. Rather, she met and married my father, a London-based Italian Maronite. Their union left her ostracised by the family but within a few years she was to find herself still in the grip of their arrangement with Cheung Ling Soo. The honeymoon was barely over when my father began to show signs of serious illness. He was a busy and successful engineer but during my early years that would change as the illness devastated his body. By 1975 my parents were in serious financial trouble. The stage was set. I was the son that Cheung Ling Soo should have had. Now, in a deal that involved a significant financial transaction, I was to be handed over and raised as his own, not for love, but so that the legacy of Kung Fu might be carried to a new generation in his name. I was to address him as ‘Lowsi’, my ‘master’. No introduction. No smile. No welcome. I was hoisted roughly onto his horse-drawn cart and, at the click of his tongue, we pulled away into the night.

As we left the airport behind, I could make out the strange shapes of trees in the half-light, while the shadows of animals moved around us. I was terrified and felt queasy with the stink that filled the air. (I was later to discover that it was the lily soap my grandfather used. It is very common among the Chinese, renowned for its antiseptic properties, but its odious perfume has always sickened my stomach.) It was to become the scent of my paranoia.

The journey seemed never-ending. When we finally came to a standstill it was pitch black. I could barely make out the shadowy surroundings, but I sensed there was a group of women standing at a gateway. Perhaps they were waiting for us. The women didn’t like me. I felt that instantly. But what had I done wrong? My mind kept flashing back to my mother. Then, with looks of disdain and a crow-like cackle, the women were gone, all except one. She was ‘Jowmo’, who had eventually married Lowsi instead of my mother; I therefore regarded her as my grandmother.

Inside the house I shivered with cold. Still no one spoke to me. I wanted to ask where I was, but when I tried to speak I was met with a finger to the lips and a harsh ‘Shush!’ I was 4 years old and completely alone in a hostile, frightening world.

The house was very strange. I was shocked when suddenly a whole wall moved. The woman ushered me towards the bed in the corner. It looked nothing like my bed at home. Sticks of bamboo lay over a rickety frame. It creaked as I climbed onto it and pinched my skin when I moved. The thin muslin sheet barely covered me, but I tucked it round my shoulders, pulled my knees up to my chest and wept silently until I fell asleep. In the days and weeks ahead I quickly learned to stem my tears.

Each day began very early, around 4 or 5 o’clock. Lowsi (which means ‘master’ or ‘teacher’) came into my room and beat me about the head with his bamboo stick to wake me. Soon I was rising before I heard his footsteps. I made sure I was up and ready to greet him. He hit me anyway. Lowsi’s beatings were brutal. In the days and weeks ahead I got used to them, but they were always hard to bear. He used fresh bamboo cane, striking me over my ears, often until I bled. There was rarely any explanation or reason. He branded me ‘Gweilo’, meaning ‘foreign devil’. It was his personal quest to ‘beat the round-eye out of me’.

The harshness of the régime to which Lowsi and Jowmo subjected me was not typical for a young boy. Children were often beaten, but I suffered far more than most. Boys in China are considered to bring good fortune and honour to a family and are often referred to as ‘little emperors’. They are spoilt and doted upon by their parents and even more so, by grandparents. The problem was that my mother had married an outsider, an Italian Maronite. She had brought shame on the family. It seemed I was to pay for the profanity.

Each morning I dutifully followed Lowsi out to the courtyard where he began his morning exercises. For several hours I shivered in my thin muslin robe but I hardly dared take my eyes off him, for fear of being beaten again. Sometimes I stole a glance up to the roof and the tops of the walls. They were decorated with some very odd sculptures including dragons, a phoenix and a man riding a hen, although most of them had been badly damaged during the Cultural Revolution.

At first I could only watch as Lowsi performed his strange movements. He made me stand very still and breathe deeply in through my nose and out through my mouth. It was mind-numbingly tedious. As the weeks went by and I began to pick up Cantonese (his language) he explained that his moves were ‘Tai Chi’, a discipline that is fundamental to the way of Kung Fu.

I quickly gathered that Lowsi was a Grand Master in the ancient martial art. He was revered by everyone in the village. That was why our house was grander than any of the others. I thought it looked a bit like the temple up on the hill.

As time went on, I began to learn more about Lowsi’s background. He originated from Northern China, but fled to Guangdong Province in the 1930s to escape the atrocities of the Japanese invasion that extended into the 1940s. He was born into the Soo Family, who had been Kung Fu practitioners for over 200 years, passing down their skills from father to son.

As a Shaolin monk, Lowsi, or ‘Cheung Ling Soo’ to give him his proper name, was proud of this 200-year-long heritage. Leaving the temple of his training, he began to develop his own styles and teach the ways of Kung Fu. He soon became a highly honoured Grand Master. Having no son of his own, he had been concerned that the Soo lineage would be broken. This was the reason I had been brought to China. Because of the links with my family, he wanted me to become his disciple and thus maintain the family heritage. Perhaps it was for this reason that he would drive me to the harshest extremes of training. As part ‘round eye’, he knew I would have much to prove. In the years ahead, Lowsi would reveal to me the secrets and treasures of the ancient art. I would become a highly disciplined, truly ‘enlightened’ disciple and an unbeatable combat warrior, hence my voyage to China at such an early age. Boys normally begin their Kung Fu training when they are very young. I had no choice in the matter at the time and could never have subsequently achieved such high standards without beginning my discipleship when I did.

To become a true student of martial arts is to accept a whole code of living, unlike anything known in the western world. Its roots are derived from spiritual discipline and the practice of Taoism. According to martial arts lore, the father of Kung Fu was the Indian monk Bodhidharma. To the Chinese he is known as Ta Mo. Legend has it that he left his monastery in India to spread the teachings of the Buddha throughout China at the beginning of the sixth century. While wandering in the mountains of northern China, he stopped at a monastery called Shaolin. Shaolin means ‘young tree’ (one that can survive strong winds and storms because it is flexible and can bend and sway in the wake of assault).

Ta Mo required that students be disciplined in the ways of meditation and the continual quest for enlightenment, but he found that the monks constantly fell asleep during meditation. He recognised that their bodies were weak and feeble, so he devised a series of exercises, explaining:

‘Although the way of the Buddha is for the soul, the body and soul are inseparable. For this reason I shall give you a method by which you can develop your energy enough to attain to the presence of Buddha.’

These exercises were a series that served a form of moving meditation. They were also highly efficient fighting moves that helped the monks defend themselves from bandits when travelling between monasteries. Even so, Ta Mo’s primary concern was not simply to develop physical strength, but with the cultivation of the intrinsic energy of ‘Ch’i’, perhaps most closely translated as ‘breath’, ‘spirit’ or ‘life force’.

It is the development of Ch’i that lies at the heart of all the Taoist arts, including martial arts, philosophy and healing. Those early days in the courtyard, mastering my breathing through hours of practice, were to become the foundation of something extremely powerful.

One day Lowsi dressed me in orange robes and took me to the local temple. The sky was a brilliant blue as we climbed the many steps to the entrance and a strange sweet smell hung in the air. ‘Incense sticks and cherry blossom,’ Lowsi said. ‘We use them as a gift to pay our respects to Buddha.’ Dutifully, I followed him as he lit some sticks on our behalf. ‘Their therapeutic aroma will help calm your mind,’ he explained. ‘As you follow the path to enlightenment you will become like the smoke rising from the incense to the heavenlies.’

As my master led me over to a quiet area to begin our meditation, I couldn’t help steal a glance at the monks who were combat training. ‘They have bound their feet and lower legs with cords,’ Lowsi said, noticing my interest. ‘This is for strength and protection as they practise their footwork.’ I watched in utter amazement at the speed and power of their kicks.

As my training progressed, I too mastered this system with its powerful long-range kicks and one-legged stance, which is known as the way of the crane. Indeed, in due time I was to master many other systems of Kung Fu. Chinese martial arts claim as many as 1,500 styles. The imitation of animals is the classical and oldest Shaolin Kung Fu exercise. My master taught me that the human, being weaker than the animal, relies on his intelligence in order to survive. Yet to truly imitate the movement and mind of a particular animal is to master the physical art of immobility and rapidity, observation and reaction, steady movement and instantaneous attack.

‘Now concentrate!’ Immediately my attention was snapped away from the disciples.

‘Focus your mind on this flame.’ Lowsi drew my eyes to the burning candle he placed in front of me. ‘Centre yourself on the inner flame and clear your mind. Now breathe.’

We spent hours in the temple, staring into the flame of a candle. I longed to close my eyes, but as they grew heavy the thwack of bamboo hit my face. Lowsi beat me at any point he thought I was losing concentration. The purpose of these hours of meditation was to get in touch with the Ch’i. I was taught that all things are products of cosmic negative and positive forces, the yin and yang, which can be harmonised in the study of Ch’i. Disciples of Taoism would describe Ch’i as energy flowing round the body. This energy, they claim, governs every bodily action, including breathing and the beating of the heart.

‘When you can completely harmonise the Ch’i in both body and spirit, you will reach enlightenment and inner peace. You will discover seemingly supernatural power within yourself,’ Lowsi taught me. ‘Harnessing the Ch’i is essential in the art of Ku Fu,’ he continued. ‘It allows for fluidity.’ Dipping his hand into a small vase of water he held it in the air until a small drop formed and lingered on the tip of his forefinger. ‘A single drop of water. Alone, it is harmless, gentle and powerless, but what on earth can withstand the force of a tsunami? Its raging waves have power to destroy earth and overcome all in its path. Learn to control the Ch’i, boy. Tap into its universal energy and you, too, will have power many times your natural strength.’

In the years that followed Lowsi’s instruction in the Ch’i became clearer to me. I understood it to be the ‘god within’, the root of my power. Harnessing my body’s energy through the Ch’i, I could break bricks with my bare hands and perform much more amazing feats. It also gave me a heightened state of awareness, to the point where I could sense the movements of an opponent in the dark and withstand immense pain by redistributing it throughout my body.

Everything about my life in China was intertwined in Kung Fu training. As a novice, I was made to do the most menial and difficult work relating to the upkeep of both our home and the temple. All the time Lowsi was preparing my body to begin training in earnest. One of the first exercises he presented to me was plunging my hands into a bucket of sand. Hour after hour I did this under his watchful eye, until my hands were sore and bleeding. After a few weeks, my skin had hardened until I no longer felt the pain. Lowsi introduced small stones into the bucket and the procedure began again. Every few days he added larger stones until I was pounding my hands, with great force, into sharp boulders without cutting or blistering.

One of my main chores was tending the animals. My ‘grandparents’ had paddy fields and we kept chickens, goats, cows and a horse. I was usually left alone to my work and I felt safe, away from Lowsi’s harsh whippings. Among the animals I could momentarily set aside the pain of my training and the hatred I felt towards him.

Trips to the market with Jowmo were another welcome relief. I had to carry huge loads, but it was better than my master’s merciless beatings. The market was noisy and colourful. People haggled and shouted to one another above the background rumble of the mah-jong houses. There were lots of live animals in cages: dogs, ducks, goats, rabbits, birds, reptiles and all sorts of strange fish on big wooden carts. I stuck close to Jowmo, afraid of being noticed by the ‘reptile man’. He was very old and bent, with a wispy grey pointed beard, a thin moustache and a face that was creased like a dried up old prune. Long yellow nails stuck to his wizened fingers, and he used his sharply pointed thumbnail to cut up the throat of the terrapins he sold. On his stall were all manner of insects and snakes: live, dead, dried or skinned.

The medicine shop was another fascinating place. I found it intriguing to look at all the items stored in jars arranged in rows on the shelves inside the shop. Inside some of the jars were assorted herbs and roots, but others contained animal body parts – beetles, bees and snakes of various shapes and sizes, all preserved in a potent-smelling liquor.

Jowmo bartered for what seemed like ages with the herbalist. I marvelled at the huge chillies, brightly coloured powders and funny-looking roots that she bought to make ginseng and ginger teas. Back on the street there were delicious smells as people sat at the roadside, cooking in large woks. It was the 1970s and it seemed that much of Guandong was under construction. Alongside the traditional shack-type stalls, giant western-style structures were being erected by barefoot or flip-flop clad Chinese, performing death defying feats on bamboo scaffolding.

We picked our way through mounds of rubble and pungent market waste, avoiding the constant pestering of people selling fortune-telling sticks. My attention was always caught by the calligraphers who set themselves up in the street with their brushes and inks. ‘They use special xuan paper, made from bark and rice straw,’ Jowmo explained. ‘People hire the calligraphers to write letters for them and prepare special announcements.’

Jowmo could hardly be described as warm towards me, but she did seem to enjoy teaching me about the ways and traditions of our people. In China there are many festivals. New Year is the most important. The Chinese lunar year is based on the cycles of the moon and the calendar cycle is repeated every twelve years, with each year represented by an animal.

I discovered that I happened to have been born in the year of the pig. There are various ancient legends telling how twelve animals came to be associated with the different years and in Jowmo’s favourite account, the pig was the last of the 12 animals which turned up to say farewell to the Buddha when he departed from earth, because he was so lazy. However, although Jowmo tended to laugh at the poor pig, it wasn’t all bad news to be born under this animal sign. Such people were reckoned to be relatively calm when facing danger, very kind-hearted and affectionate while possessing a tremendous determination to finish any task they are engaged in. As New Year drew close, there was a great sense of excitement in the community. The twelfth moon was set aside for the annual house cleaning. Jowmo referred to it as the ‘sweeping of the grounds’. Every corner of the house had to be thoroughly cleaned. I helped her hang large scrolls of red paper on the walls and gateway. In beautiful black ink they pronounced poetic greetings and good wishes for the family. We decorated the house with flowers, tangerines, oranges and large pear-shaped grapefruits called pomelos. ‘These will bring us good luck and wealth,’ Jowmo said, as she carefully arranged a display of fruit. (The word for tangerine has the same sound as ‘luck’ in Chinese, and the word for orange has the same sound as ‘wealth’.)

‘When the house is clean we will prepare the feast and bid farewell to Zaowang, the kitchen god,’ Jowmo told me. ‘Tradition says that Zaowang returns on the first day of the new year when all the merrymaking is over.’ There was lots of work to be done. All food had to be prepared before New Year’s Day. That way, sharp instruments, such as knives and scissors, could be put away to avoid cutting the ‘luck’ of the New Year.

On New Year’s Eve the family gathered at our house. They travelled from all over China and I was curious to see my grandmother setting empty places at the table for family members who could not attend. ‘This is to symbolise their presence at the banquet, even though they cannot be with us,’ she explained. I wondered if there was a place for my mother, but I never asked. Many of the guests treated me with the same disdain as my grandfather, but at least there were some other children – my ‘cousins’, all girls – to play with. There was also a large lady with a big smiling face who winked at me mischievously. She was Lowsi’s sister, Li Mei, meaning ‘plum blossom’. His other sister, Li Wei, did little to live up to her name, ‘beautiful rose’. To me, she was far from beautiful. She looked at me through the same shrew-like eyes as my Lowsi. At midnight, following the banquet, the other children and I were made to bow and pay our respects to our grandparents and the other elders. I did as I was told, but I still hated them.

When New Year’s Day came we were given red ‘Hung Bao’ envelopes. They contained good luck money. Everyone wore new clothes, although with the country still feeling the effects of the Cultural Revolution, this meant drab dark grey suits.

I was quickly growing accustomed to my new life, but I soon worked out that, among these people, I would always be an outsider. In England, my mother had been proud of my oriental looks but, to the Chinese, I was very much a ‘foreign devil’. I was 6 years old when I discovered that such prejudice, even in children, can be very cruel.

One day, on the way home from the market with Jowmo, we stopped to rest by the village pond. As Jowmo lay back in the shade, I wandered around, casting stones into the water. Suddenly a group of boys not much older than myself surrounded me. My grasp of Cantonese was still pretty limited, but I understood enough to make out the words of one boy. ‘Hey, Round Eye, what are you doing here?’, he asked threateningly, spitting at me as he spoke. In shock, I tried to understand what I had done wrong and what they were saying to me. ‘He doesn’t even speak our language,’ scoffed another boy, giving me a sharp slap in the mouth. ‘Come on, Round Eye, let’s hear you say something.’ I grappled for words, horrified by the taste of blood in my mouth. Then came another blow to my face. This time it was so hard that I lost my balance and went flying backwards in the mud.

At once, all the boys were upon me, beating, slapping, scratching and dragging me by my hair. Fighting for breath, I screamed out to Jowmo but she didn’t come. They kept on and on, shouting as they struck me; the noise of their abuse span round and round in my head until eventually I began to black out. Then silence. No pain. Nothing.

I awoke in hospital, some days later. Both arms and one of my legs were cased in plaster. As I moved, a stab of pain ran through my whole upper body.

One night, whilst still in hospital and barely in a state of consciousness, I was aware of Lowsi and another man standing by my bed. I could only catch a little of what they were saying, but I gathered that they knew the gang of boys who had set upon me.

‘Children of the Triads, from Shanghai,’ the stranger said, ‘visiting the local family.’ ‘They did not know who this boy is then,’ said Lowsi sternly. ‘Quite obviously not.’ ‘Am I to understand they have been dealt with?’ ‘Oh yes, the family has dealt with them most severely and the elders wish to meet with you tomorrow to seek your forgiveness and pardon.’

In the coming years the Shanghai boys were careful to stay away from me. Being from Triad families (the notorious Chinese mafia) they, too, were taught the practice of Kung Fu, but everyone knew that they would never receive the same level of training as me. Had they realised I was the disciple of the highly revered Cheung Ling Soo, they would never have dishonoured my family in this way and would have approached me in respectful trepidation. Such incidents are not easily forgotten among the Chinese. Years later the boys still lived under the weight of their childhood error. On one occasion, many years later, when I returned to the village as an adult, after a period of absence, I learned that one of the attackers believed I had come back to claim my revenge. He was so scared that he was preparing to move his family out of the area.

Following the attack I spent many weeks in hospital, but I was barely free from the plaster cast when my master had me back in the courtyard, doing the most rigorous of physical exercises. The pain was so great that tears stung my eyes. This, I knew, my master would not tolerate. Sure enough, as a single droplet escaped down my cheek I felt the thrash of the bamboo across my ears. Hatred boiled up inside me. I was 6 years old but every fibre of my body, every drop of my young blood screamed out in loathing.

That night I woke in a cold sweat. I could hear the croak of insects and knew it was long before morning. The house was still and peaceful, but haunted dreams brought the frenzy of my hatred to fever pitch. Tossing and turning on my bed, I winced in the heat of fresh wounds. The image of Lowsi and his wicked bamboo cane tortured my mind. It would never end. But how could I stand even one more day? There was only one thing I could do.

As I padded silently through to the kitchen I felt the whole house would hear my heartbeat. Lowsi kept some of his combat cleavers in a large chest. We cleaned and polished them every day, so I was very familiar with the feel of them. I chose one and held it up, turning it so it reflected light onto my face. The blade was razor sharp.

A shaft of moonlight broke through the bamboo shutters and I could see Lowsi’s sleeping form. I stood at a distance, looking at him, anger and repulsion sweeping over me in waves. Suddenly, I was aware of the heaviness of my breathing. Ironic, that I would draw on his teaching to calm myself for silent strike. ‘Focus on the Ch’i, concentrate. Control your body through your mind.’ With my breathing in check I moved stealthily towards the bed. He was motionless.

I raised the cleaver above his heart.

Chapter 3

‘Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name …’ It was a prayer my father had sometimes recited to me at bedtime. He said he was Catholic because he was Italian, and God loves Catholics. But if ever God existed, he’d obviously forgotten about me now. He had no place in my brutal world. Everything about my life in England was becoming nothing more than a hazy, confused memory. I couldn’t even picture my father’s face anymore.

Confucius taught: ‘Peace in the state begins with order in the family … The people who love and respect their parents would never dare show hatred and disrespect to others.’ He also spoke of love, virtue and honour as being the highest ideals in society.

I knew much about honour and virtue. These things were beaten, quite literally, into every cell of my young body. But love? What was love? I had never known it. I was an unwanted child, a ‘foreign devil’ who brought nothing but shame and bad fortune to those who were supposed to love me. No wonder then that my 7-year old heart could be consumed by such hatred. It came easily.

With the cleaver tight in my hand, I let the full weight of my arm fall.