Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

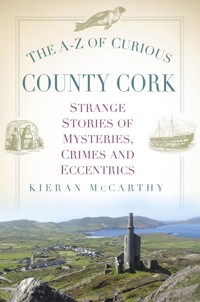

County Cork is the largest county in Ireland, with a heritage that has been recorded, celebrated and commemorated over many centuries. This book explores the historical curiosities within the county's sweeping river valleys, epic mountainous locations and sprawling coastline. There are many sites and stories to discover that whisk the reader off through ancient underground worlds, myth-making landscapes and ghostly tales. From apparitions to zoomorphic images, Cork possesses a myriad of tales to stop the explorer in their tracks, all of which enhance County Cork's strong sense of place.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to my niece, Katie, may you forever smile.

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Kieran McCarthy, 2023

The right of Kieran McCarthy to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 80399 491 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Introduction

A

Abandon

Anomaly

Anthem

Apparition

Appointment

Arm

Astronomical

Autopsy

B

Beacon

Bird

Black

Blood

Bowl

Brick

Bucket

C

Censor

Children

Clapper

Cloak

Colony

Commune

Cousins

D

Dairy

Death

Destruction

Disease

Ditch

Dove

Duplicate

E

Ears

Enrich

Entrepreneur

Exhibitionist

Expedition

Expensive

F

Family

Ferry

Fish

Fluorescent

Folly

Font

Footprints

Fragment

G

Game

Garden

Generosity

Giant

Gift

H

Hag

Haunted

Headless

Horse

Hulk

I

Ideas

Identity

Illegal

Infatuation

Inflation

Inscribed

J

Jack

Japanese

Justice

K

Kindred

King

Kitchen

L

Lament

Landmark

Legendary

Lines

Lovers

Lured

M

Manuscript

Marriage

Martyr

Massacre

Master

Mine

Monster

Moonlighting

Movie

Murder

Mystery

N

Nation

Nationality

Neutral

Newspaper

O

Old

Orientation

Outpost

P

Paper

Penal

Petticoat

Pirate

Poison

Prison

Promise

Q

Quake

Quirky

R

Radar

Raid

Relax

Remember

Route

Row

S

Saga

Scarecrow

Seaweed

Shriek

Slayer

Smuggle

Sound

Store

Stranded

Survival

Swim

Sword

T

Table

Tall

Torch

Tornado

Training

Transmission

Tunnel

U

Underground

Underwater

Underworld

Unfinished

United

Use

V

Vanish

Village

Vindication

W

Walk

Warrior

Wave

White

Wind

Window

Wireless

Witchcraft

Wren

X

Xenomania

X Marks the Spot

Y

Yanks

Z

Zeal

I would like to sincerely thank the commissioning and editorial staff at The History Press for continuing to put their faith in my books and for the valuable advice and assistance they always provide. I would like to express my gratitude to my parents, my family, to Marcelline and my public support for continually pushing me to explore, think about and write about Cork city, its region and its cultural heritage.

For thirty years, Kieran has actively promoted Cork’s heritage with its various communities and people. He has led and continues to lead successful heritage initiatives through his community talks, city school heritage programmes, walking tours, newspaper articles, books and his heritage consultancy business. For the past twenty-four years, Kieran has written a local heritage column in the Cork Independent on the history, geography and its intersection with modern-day life in communities in Cork city and county. Kieran is the author of thirty local history books. He holds a PhD in Geography from the National University of Ireland Cork and has interests in ideas of landscape, collective memory, narrative and identity structures. In June 2009, May 2014 and May 2019 Kieran was elected as a local government councillor (Independent) to Cork City Council. Kieran is Lord Mayor of Cork for 2023–24. He is also a member of the European Committee of the Regions. More on Kieran’s work can be viewed at www.corkheritage.ie and www.kieranmccarthy.ie.

‘Curiouser and curiouser!’ cried Alice in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Such a famous literary phrase bounced around in my head as this book took shape. At the outset this book has been borne out of my own personal curiosity for many years now to venture off the main roads of County Cork to explore the ‘wonderland’ of cultural heritage in County Cork. Just like Alice’s feeling of being lost, all too often I have felt lost on my scooter motorcycle in the county’s precious winding and scenic roads. However, one is never truly lost in an age of Google Maps. But in any given day, I could be just a few kilometres from home and feel like being a grand explorer of a forgotten countryside.

The added task of picking over 100 curiosities of County Cork was also going to be a challenge. It is difficult to define what a curiosity is. Such a distinction varies from one person to another. The importance of a curiosity in one locale may not be a curiosity to another locale. The stories within this book, and which I have chosen and noted as curiosities, are ones that have lingered in my mind long after I found them or they brought me down further ‘rabbit holes’ of research.

Some curiosities are notable and well written about or some exist through a neighbourhood monument, a basic sign or a detailed information board showcasing they exist. Some are bound up with local folklore and referred to in a place name. Others could be deemed as strange events. However, all define the enduring sense of identity and place of a locale.

Being the largest county in Ireland, Cork has the advantage of also having the largest number of cultural heritage nuggets. However, with that accolade comes the conundrum of what nuggets to pick from. As with any A–Z of anything, it does not cover every single aspect of a particular history, but this book does provide brief insights into and showcases the nuggets and narratives of cultural interest that are really embedded in local areas. It also draws upon stories from across the county’s geography.

Much has been written on the history of County Cork. There is much written down and lots more still to be researched and written up. The county is also blessed with active guardians of its past. In particular, there is a notable myriad of local historians and historical societies, which mind the county’s past and also celebrate and commemorate it through penning stories in newspaper articles, journals, books and providing regular fieldtrips for the general public. There is also the impressive heritage book series on County Cork, published by the Heritage Unit of Cork County Council.

In addition, this book builds on The Little Book of Cork (2015) and The Little Book of Cork Harbour (2019), both History Press publications. It can be read in one go or dipped in and out of. I encourage you, though, once you have read it, to bring it out into the historic county of Cork to discover many of the curiosities up close and personal.

Enjoy, Kieran.

ABANDON

Just under 5km to the south-west of Macroom lies the Gearagh – a unique treasure trove of nature comprised of river channels flowing through an ancient forest system. Resulting from the flooding of an immense oak forest, a village and extensive farmland during the Lee Hydroelectric Scheme in the mid-1950s, the area is a miniature Florida swamp extending over 4.8km in length.

Annahala village was a little community with pockets of houses here and there. Some of the land had underlying limestone, which provided for fertile soil, while the rest of the land was boggy and marshy. At one time, Annahala had been an important lime-producing area with many lime kilns and a large population. Fuel for the kilns came from the Annahala bog, which had some very good turf banks, and timber from the Gearagh was also plentiful.

A Cork Examiner reporter visited the area on Friday, 26 October 1956, three days after the sluice gates of Carrigadrohid Dam had been closed. The reporter recorded the abandonment of the village in lamentful detail:

House in Annahala village, The Gearagh, Macroom, 28 October 1956. (Irish Examiner)

Some of the families had already left and were established in their new homes. Some are on the way. Some have nowhere to go! … What trees there were have been cut and removed. From the flat terrain, newly created ruins stuck out like sore thumbs. As owners abandoned their cottages, slates and roofs were pulled off, and, in some cases, walls tumbled in. In one instance – that of the Gearagh’s sole shop – only the concrete floor and foundations remain. But wisps of smoke still trickled from a few chimneys early yesterday.

Today, only the rectangular foundations of the houses survive amidst the undergrowth as well as the overgrown central small road through the village.

ANOMALY

(Rostellan Portal Dolmen)

To Cork and Irish archaeologists, the motives behind the building of the dolmen in Rostellan in north-east Cork Harbour is a mystery. It has three upright stones and a capstone, which at one time fell down but was later repositioned. It has a comparable design to portal tombs but this style of tombs is not familiar at all to this region of the country. For the visitor, the site is challenging to access. The beach on which it sits gets flooded at high tides and access across the local mudflats is tricky and dangerous. It is easier to get to it with a guide through the adjacent Rostellan wood. The dolmen may be a folly created by the O’Briens, former owners of the adjacent estate of Rostellan House, on whose estate an extensive wooded area existed. The house was built by William O’Brien (1694–1777), the 4th Earl of Inchiquin, in 1721.

ANTHEM

After the unsuccessful attempt at a rising in Ireland in March 1867, the principal participants, Colonel Thomas J. Kelly and Captain Timothy Deasy, two well-known Fenian leaders, emigrated to Manchester. They were arrested the following September.

Some of the Irish community in Manchester were determined to help them escape. However, the hold-up of the van while the prisoners were being transferred from Manchester to Salford Jail did not go according to plan. A shot fired through the lock in order to break it killed a policeman who was inside. The two prisoners escaped.

About thirty Irish people in Manchester were arrested on suspicion. Eventually, all were released except five. These were charged with wilful murder and sentenced to death. During the trial the condemned men started chanting the slogan ‘God Save Ireland’. Three of the men were eventually taken to the gallows.

A few days after the executions, County Cork’s well-known poet Timothy Daniel Sullivan wrote the words to a song and titled it ‘God Save Ireland’, weaving it with the air of an old song. Sullivan’s song became so popular that later it was considered the Irish national anthem for a time.

Bantry-born Timothy Daniel Sullivan (1827–1914) began his career as an artist, then a journalist, obtaining a position on the staff of the Nation newspaper in 1854. He contributed many songs and articles to this paper. It was with simple ballads comprising themes of home and fatherland that he particularly excelled. He became editor and proprietor of the newspaper in 1876. Four years later, he became Nationalist member of Westminster Parliament for Westmeath, a seat he held until 1885 when he won the Dublin City constituency, which he represented until 1892. For the following eight years he was member for West Donegal.

APPARITION

On 22 July 1985, it was alleged a statue of the Virgin Mary in the grotto at Ballinspittle had moved. A local Garda saw the statue first move in July 1985 – and then photographed it. On dismissing the idea that he had a shake in his hand while taking a picture, he noted to the Cork Examiner that his camera was on a tripod, which held it perfectly steady. ‘I took several pictures using a 80-200 Makinon zoom lens on this Olympus SLR camera. One picture showed the statue in its usual way but a follow-up picture taken from the same vantage point and without shaking the camera seems to show the arms in a different position.’

Events at the statue soon ensued. A local 100-person committee organised days of devotions. A bulldozer even worked long hours to prepare a 1-acre car park made available by a parishioner in a disused quarry midway between the village and the shrine. There were also toilets constructed by Cork County Council.

CIE – the national bus company – put on a number of bus services from the city and provincial towns. A number of private operators organised bus trips from many parts of the country. All roads within a mile of the shrine at each side were sealed off and pilgrims were advised to come well clad and to be prepared to stand for a long period. The crowds assembled on the slope opposite the shrine.

A serving sergeant in Cork city at the time saw the statue move two days after the first report in July 1985. He was among a crowd of several hundred people saying prayers and singing hymns in front of the grotto when suddenly, without warning, there was a gasp from the crowd as the statue, which is embedded in concrete, appeared to be airborne for half a minute. He noted: ‘I was so convinced it was a fraud that I climbed up into the grotto the next morning and tried to shake the statue but it wouldn’t budge. I checked the back, the sides of it for any trip wires, but I couldn’t find anything.’

In the summer of 1985, over 100,000 people visited Ballinspittle in the hope of seeing the statue move. A spate of similar claims of moving statues occurred at about thirty locations across the country.

The advent of the nineteenth century coincided with the collection of folklore of the appearance of the Virgin Mary on the coastal side of Inchydoney Island near Clonakilty. Poet and story collector Joseph Callanan, in his works, The Recluse of Inchidoney (1829), tells of a local story of the Virgin Mary standing at one point in time on an elevated sand bank. According to folklore, she was discovered kneeling there by the crew of a vessel that was coming to anchor near the place. They sniggered at her and disrespected her, upon which a storm arose and devastated the ship and her crew. Attached to this tale is the ‘Virgin Mary’ shell story, about a fragile shell of the sea potato, a spined, urchin-like creature that burrows in the sand. It is told in the area still today that the ‘M’ shape of tiny perforations on the upper surface are said to denote Mary, the Mother of God, the dots indicating the number of beads of the Rosary, and, on the reverse side, some see the Sacred Heart.

APPOINTMENT

At one time, Elizabeth St Leger (1693/1695–1773/1775) of Doneraile House (later Mrs Aldworth) had the distinction of being the only female Freemason. Her appointment was more by accident than design. The North Cork Freemason’s Lodge was held in Doneraile House in a room to the west of the entrance hall. Elizabeth was reading a book in an adjoining room, the back panel of which was under renovation and roughly put together. She fell asleep.

Elizabeth was awakened by hearing voices in the next room. Seeing a light through the spaces in the wall, she watched the proceedings of the Lodge. Becoming alarmed, she attempted to escape but was challenged by Lord Doneraile’s butler, who called His Lordship. Elizabeth was placed in the charge of some of the members while her case was deliberated upon by others. It was decided that the only way out of the difficulty was to make her a Freemason. She agreed, making her the first recorded female Freemason.

ARM

Saint Lachtin’s Arm is a curious religious relic that was linked with Donoughmore Church. It is dated to c.1120. It was created to sheathe a human bone, supposedly belonging to Saint Lachtin. For much of the medieval era, the guardians of the arm were the Healy family.

The shrine comprises a hollow core of yew wood and is about 400mm tall. Elaborate bronze panels with zoomorphic interlacing, highlighted with silver inlay, decorate the wooden core. Similar patterns can be viewed on the hand, which is cast in bronze. Unusually for hand shrines, the fist is clenched, which emphasises the hand’s distinctive nails. The shrine carries writings, one of which is devoted to its patron. This text reads: ‘A prayer for Maolseachnail Ó Callaghan, Ard Rí of the Ua Ealach Mumhain who made this shrine’. Maolseachnail died in 1121. The arm is now on display in the National Museum, Dublin.

St Lachtin’s Arm relic on display at the National Museum, Dublin. (Kieran McCarthy)

ASTRONOMICAL

Skibbereen-born Agnes Clerke can boast of having left a lasting legacy, not just on County Cork but on the universe. She had a crater on the Moon named after her in 1881. Clerke Crater lies at the edge of the Sea of Serenity.

Born in 1842, Agnes was sent to private education. Her family home in Skibbereen had a large library containing the classics in literature science, with technical equipment such as microscopes and telescopes and encyclopaedic connections from the world of nature. Agnes was attracted to the subject of astronomy through the influence of her father, John William, who mounted a 4in telescope in the family garden at night. Her mother influenced Agnes to be proficient in the rendition of old Irish airs on the harp and piano. By the time Agnes was 15 she had already written the first few chapters of her History of Astronomy.

Due to her delicate health, Agnes, with her mother and sister, spent at least six months of each year from 1867 to 1877 in Italy, in Naples, Rome or Florence. Agnes became fluent in several languages, including Italian, Latin, Greek, French and German.

In 1877, Agnes wrote an article during the height of the Sicilian Mafia, which was accepted for publication in the prestigious Edinburgh Review. Her writing was highly regarded and she became a regular contributor to the journal, penning over fifty articles, with many devoted to science and astronomy. Her book – A Popular History of Astronomy During the Nineteenth Century – was described by scientific writers as a masterpiece. From this came a nomination for a crater on the moon to be named after her.

In 1890, Agnes became a founder member of the British Astronomical Association, which provided facilities and organised events for anyone interested in astronomy. She went on to write book after book on all aspects of this branch of science.

AUTOPSY

On an information panel high up in Cousane Gap near Keakill, overlooking Bantry Bay, one encounters the story of body snatchers. In the early nineteenth century, bodies were dug up and robbed from the local cemetery in Kilmocomogue. They were for sale and use in anatomy classes in medical schools in Cork city to meet the necessity to carry out autopsies to study more about human anatomy and educate their students. It was legal for surgeons to dissect the bodies of convicted murderers, who were hanged for their crimes. But the small number of bodies handed over was not enough to meet the growing science of anatomy. A horse and cart conveyed the bodies from Kilmocomogue. However, the immoral activity was eventually targeted by a local vigilante group, who safeguarded freshly dug graves.

BEACON

Atop a cliff face, near Baltimore is the unique Baltimore Beacon, which provides a sweeping viewpoint over Baltimore Harbour and Sherkin Island. The striking conical, white-painted Baltimore Beacon, sometimes called the ‘pillar of salt’ or ‘Lott’s wife’, is approximately 15.2m high and 4.6m in diameter at the base. Towards the end of July 1847, Commander James Wolfe, Royal Navy, notified the Ballast Board that he had recently completed a survey of Baltimore Harbour and observed the need for a beacon warning ships off the eastern point of the southern entrance to the harbour. It was over a year later, on 6 July 1848, before the Board invited the secretary to seek permission from Lord Carbery for a piece of ground 9.1m in diameter on which to build a new beacon.

BIRD

In the late summer of 1945, Professor Michael J. O’Kelly excavated sections of a ringfort in the townland of Garryduff on a small hill between Fermoy and Midleton. The fort was a small circular structure with a single rampart, which was first brought to notice when some shards of pottery were discovered by the landowner and were given to the professor. An excavation of the interior of the fort revealed several hearths, many postholes and some poorly preserved paved floors.

In an information report in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society in 1946, Professor O’Kelly outlines a beautiful and curious find. It was a small gold ornament which was in the form of a bird – a wren, to judge the bird’s outline. The body had a beautiful pattern of scrollwork executed in beaded gold wire filigree. The object was constructed from a thin foil of gold beaten up into a convex form so as to give an impression of the roundness of the bird’s body.

The dimensions of the object are extremely small – just 1.5cm. In other words, the whole bird is about the size of one little fingernail. One can only admire all the more the high level of technical skill shown by the craftspeople who executed such work.

Michael J. O’Kelly’s picture of the Garryduff Bird. (Cork Public Museum)

In a subsequent excavation report, published in 1963, Professor O’Kelly found no trace of military activity at the fort and concluded that the inhabitants of Garryduff were a peaceful but well-off community dedicated to their craftwork. Today, the bird piece can be viewed in Cork Public Museum.

BLACK

By the thirteenth century, the Celtic Church in Ireland was in decline. Across Europe, though, hundreds of thousands of young people were joining new and austere monastic orders, such as the Cistercians, Franciscans and Augustinians. Gaelic and Norman noblemen competed for the honour of being patron to the new religious orders. Alexander Fitzhugh, the Norman Lord of Castletownroche, created Bridgetown Priory in north Cork sometime between 1202 and 1216 for a community of Augustinian canons.

Up to 300 canons ended up living there and became known as the black canons because their habits (clothing) were black from head to toe. The canons were priests who had taken vows of poverty, obedience and chastity. They resided in the community according to the rule of St Augustine.

Fitzhugh gave the Augustinians 13 carucates of arable land, pasture and woodland, one third of his mills and fisheries and all tolls from the bridge that once stood there. Abbeys, priories, friaries and nunneries were soon established in Fermoy, Buttevant, Ballybeg, Glanworth and Castlelyons.

The priory prospered for over 200 years. At the time of its dissolution by King Henry VIII in 1541, its buildings, including a church with belfry, dormitory, hall, buttery, kitchen, cloister and cellar were all in ruins, its lands underpopulated and the property was worth less than £13. The buildings passed through almost a dozen landowners until it was taken over by Cork County Council.

In recent decades ongoing conservation work, facilitated by Cork County Council, on Bridgetown Priory has allowed the general public to explore the old ruins. Information panels reveal the secrets of the ruins and that the remains are substantially of the thirteenth century. They are among the most extensive of any religious house established in Ireland in that period.

BLOOD

In the parish of Durrus near Bantry lies Loch Na Fola, or Blood Lake. The 1937–38 National Schools Folklore Collection records that long ago, a man had to go to Durrus to fetch a priest for a sick person. He had to pass a place on the hill where a ghost was often seen. Near this place, there was a lake. He rode his horse to this location and took with him a scythe.

The man and his horse arrived at the point where the ghost was seen. Suddenly, his horse automatically halted. A ghostly tall man emerged from the landscape and strode before the horse on the road. The man raised his voice to the stranger, ‘Come off the road and let the horse pass’, but the ghost did not move. He reiterated his call several times, but the ghostly figure would not move from where he was.

The man grew angrier, dismounted his horse and cried, ‘Are you going to come off the road and let the horse pass?’ but the stranger did not stir. The man then struck him on the head with the scythe, which he had in his hand. The stranger fell to the ground and covered the whole place with blood. The man jumped on his horse and fled.

The blood steadily flowed into the adjacent lake, and in the morning it was overflowing with blood. Ever since, that lake has been called Loc Na Fola or, in English, Blood Lake.

BOWL

As a rich religious complex, it is easy to be curious about the pilgrimage traditions at St Gobnait’s ruins in Ballyvourney. For example, touching St Gobnait’s bowl three times forms part of the pattern of pilgrim acts.

The saint, through folklore, is represented as a woman of action. An invader of the area intended to construct a fortress on a hill near where the industrial estate is now located. St Gobnait’s Hill overlooked the site and she threw an iron bowl at the structure, flattening it. The bowl returned to St Gobnait’s hand, boomerang fashion.

Gobnait was also renowned as a beekeeper. The bees may well be considered her army. Rustlers were creating havoc in the district, stealing sheep and cattle, and the locals asked for Gobnait’s help. She dispatched her bees on the trail and they routed the rustlers in a short time.

Gobnait is alleged to have been a native of the Aran Islands. In a vision, she was told to build her convent and church where she found nine white deer grazing. She travelled through Connacht and Munster in her quest. Many places in which she stayed are now known as ‘Cill Ghobnait’, or Kilgobnet. In Clondrohid, near Macroom, she saw some white deer, but not until she got to the townland of Gort na Tiobratan did she find exactly what she sought.

Since time immemorial, St Gobnait’s Day, which is on 11 February, has been a local holiday. The saint’s grave and marked spots are places where pilgrims pause for devotion and reflection. In addition, a medieval carved wooden statue is shown on her feast day at the local church, whereby ribbons are aligned the length of it. The ribbon is supposed to then be brought back to your home, where it can be used to ward off and cure sickness.

BRICK

One cannot but ponder on the tall, old chimney of Youghal Brickworks. It is such a recognisable landmark for travellers along the N25 Youghal bypass. Founded in 1895, in over a decade the Youghal Brick Company’s factory was declared the most modern brick plant in the British Isles.

In 1913, the prestigious trade body, the British Brickmaker’s Association, dispatched a delegation to Youghal Brickworks to examine the plant because of statements that a revolutionary technique of firing brick, which halved fuel consumption, was being successfully employed there. The claims were right – and the delegation duly reported back in very favourable terms to the British Clayworker’s Journal.

It was manager J.R. Smyth who was responsible for progress. In Tony Breslin’s thesis work on the brickworks, he outlines that Smyth was originally employed by H.R. Vaughan of Belfast, who owned the Laganville Brick Company. He was sent to Youghal to supervise the installation of a boiler bought from Laganville, and was invited to stay on to manage the newly incorporated Youghal Brick Company.

Soon after his arrival in 1896, J.R. arranged with a firm of German kiln constructors to build a Hoffman kiln. Invented by Frederick Hoffman in 1850, this was the first continuous-firing kiln and it had brought a new impetus to the brickmaking industry. It is the remains of this kiln, with its mighty chimney stack, which can be seen on the Youghal Brickworks site today – the only major structure now left of the entire complex.

Corrin Cross and cairn, present day. (Kieran McCarthy)

The Hoffman was the most up-to-date kiln of the time. It became obsolete in less than fifteen years because it had a major drawback. It required a very tall chimney to draw down sufficient draught to operate properly. The performance of the kilns was thus, to some extent, dependent on the weather.

J.R. Smyth soon realised that the Hoffman, whatever advantages it had over earlier kilns, was still somewhat crude and wasteful. He therefore went to Germany, where kiln technology was more advanced than anywhere in the world, and he returned with new ideas. As a result, the Youghal Brick Company invested £3,000 in modernising the factory, including the installation of a revolutionary kiln designed by James Buhrer.

Between 1890 and 1920, the Youghal Brick Company was the leading Munster manufacturer and its products were used to build much of modern Cork. However, by 1929 it was all over. The Great Depression, the increase in coal prices and the rise of the concrete block became enormous economic obstacles.

BUCKET

The cairn atop Corrin Hill forest park overlooking Fermoy possibly may date to the early Bronze Age and it has been speculated that it is surrounded by a possible Iron Age hillfort. Local folklore relates an ancient story of a prince of the Fír Maigh Féine, who was cautioned by a Druid that his young son would perish in a drowning accident.