Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

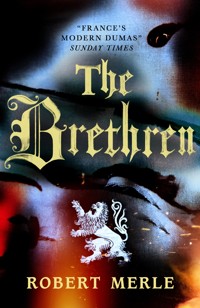

The Périgord of sixteenth-century France is a wild region on the edge of the reaches of royal authority-its steep, forested valleys roamed by bands of brigands and gypsies, its communities divided by conflict between Catholics and converts to the new Protestant faith, the Huguenots.To this beautiful but dangerous country come two veterans of the French king's wars, Jean de Siorac and Jean de Sauveterre, The Brethren-as fiercely loyal to the crown as they are to their Huguenot religion. They make their home in the formidable chateau of Mespech, and the community they found prospers, but they are far from secure-religious civil war looms on the horizon, famine and plague stalk the land, and The Brethren must use all their wits to protect those they love from the chaos that threatens to sweep them away.The Brethren is a lusty, exhilarating blend of adventure and romance set against the backdrop of a critical period in European history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 657

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fortunes of France

THE BRETHREN

ROBERT MERLE

Translated from the French by T. Jefferson Kline

Shall we never see France’s fortunes reversed?

Or shall we remain for ever despised and downtrodden?

MICHEL DE L’HOSPITAL

Contents

FOREWORD

The Brethren is a chronicle situated in the second half of the sixteenth century, beginning two years before the death of François I (1547) and ending a year after the Meeting of Bayonne (1565).

It is a concentric tale, whose first circle is a family, second circle a province and third a kingdom, whose princes receive no more attention than is necessary to understand the happiness and unhappiness of those who, far away in their baronial courts, depended on their decisions.

The family which I have imagined (carefully feeding this fantasy with precise historical documents) was Protestant and lived in the southern part of the Périgord region, midway between two villages which were then called Marcuays and Taniès—the latter overlooking a small river which fed its mills. Parallel to this river there winds a road that led—and, indeed still leads—to Ayzies, now called les Eyzies. Mespech, the name of the castlery acquired by the Siorac family, comes from mes, the word for house in langue d’oc, and pech, hill.

I am not Protestant myself, so it is no Huguenot austerity that drove me to complete my documentation without aid of any kind. It was, rather, a kind of sensual pleasure: to ensure that I would miss none of the charming, vivid, horrible or savoury details that abound in the memoirs of this period.

The Brethren, as a story, forms a complete whole and can stand alone. I have not excluded the possibility of providing a sequel, yet refuse to commit to such a project in advance, desiring to preserve my liberty as long as possible, that is, until I begin the first page of my next book.

ROBERT MERLE, 1977

1

MY FAMILY’S CLAIM to nobility does not extend very far back. In fact, it originates with my father. I say this without the least sense of shame. You must understand that if I were out to hide anything I would never have begun this story at all. My design is to write it straight out, without any deviation, the way you’d go about ploughing a field.

Some have dared to claim that my great-grandfather was a mere lackey: a falsehood which I shall be glad to prove to anyone who will listen. In fact, my great-grandfather, François Siorac, never served a day under anyone. He owned and worked with his own hands a rich piece of farmland near Taniès, in the Sarlat region. I cannot tell you the exact extent of his land, but it was neither small nor unproductive, judging by the fact that he paid the highest tithes to the king of any man in his parish. Nor was he a miser, since he gave ten sols a month to his curate so that his younger son Charles could study Latin, hoping, no doubt, to see him become a priest in his turn.

My grandfather Charles was a handsome man, whose beard and hair verged on red, like my half-brother Samson’s. He learnt his Latin well, but preferred adventures to sermons: at eighteen he left his village to seek his fortune in the north.

He found it, apparently, since he married the daughter of an apothecary from Rouen, to whom he was apprenticed. I cannot imagine how, being an apprentice, he managed to study for his apothecary’s exams, nor do I even know whether he passed them or not, but at the death of his father-in-law he took over his shop and did remarkably well. In 1514, the year my father was born, he was prosperous enough to acquire a mill surrounded by good farmland, some ten leagues from Rouen, which he named la Volpie. It was at this time that between “Charles” and “Siorac” the particle “de” was inserted to indicate nobility, an addition my father made much sport of, but maintained. And yet I’ve never seen on any of the documents preserved by my father the title “nobleman” preceding the signature “Charles de Siorac, lord of la Volpie”: proof that my grandfather wasn’t out to fool anyone, like so many bourgeois who acquire land only to lay claim to a title never granted them by the king. False nobles abound, as everyone knows. And, to tell the truth, when these bourgeois fortunes grow fat enough to merit an alliance, the real nobles don’t look too closely.

My father, Jean de Siorac, was a younger brother, like his father Charles before him and like me. And Charles, remembering the costly Latin lessons old François Siorac had provided for him, sent Jean off to learn his medicine in Montpellier. It was a long journey requiring a lengthy stay and a great sacrifice of capital, even for an apothecary. As he grew older, however, Charles’s great dream was—God willing—to see his eldest son Henri settled in his apothecary’s shop, his younger son Jean established as a doctor in town, and the two of them, squeezing the patient from either side, prospering grandly. His three daughters counted but little for him, yet he provided each of them enough in dowry so that he should never be ashamed of their station.

My father received his bachelor’s degree with a licence in medicine from the University of Montpellier, but he never defended his thesis. He was forced to flee the town two days before his defence, fearing that his last look would be heavenward as he dangled from a noose, after which he would be quartered and, as was the custom of the place, his quarters hung from olive branches at each of the town gates. This fact gave me cause to shudder when, in my turn, I entered Montpellier one sunny morn, thirty years later, and confronted the rotting remains of some women, hanged from the branches of these trees, shamelessly laden, as if with their own profusion of fruit.

Today, I have trouble imagining my father thirty years ago, just as wild as I am now, and no less attracted by a pretty skirt. Yet it is undoubtedly over some unworthy wench that my father fought an honourable duel and skewered the body of a petty nobleman who had provoked him. An hour later, spying the archers coming to arrest him in his attic, Jean de Siorac jumped from a rear window onto his horse (luckily still saddled), and galloped full tilt out of town. Bareheaded and dressed only in his doublet, with neither coat nor sword, he headed towards the hills of Cévennes. There he sought refuge with a student who was spending six months in the mountains preparing his medical exams for Montpellier. He later crossed the Auvergne region and headed to Périgord, where old François Siorac armed and clothed him at his own expense and sent him on to the home of his son Charles in Rouen.

By this time a formal complaint had been lodged with the parliament of Aix by the parents of the late petty nobleman. They succeeded in making such an enormous stir that even my grandfather’s considerable influence as apothecary of Rouen did not make it safe for Jean de Siorac to show himself in daylight.

All of this transpired in the same year that our great king, François I, ordered the conscription of a legion of soldiers from each of the provinces of his kingdom. This was a wise decision, which, had it been continued, would have spared us the wartime use of the Swiss Guard, who fought bravely enough when they were paid, but, when they weren’t, set about pillaging the poor peasants of France faster than our enemies could.

The Norman legion, a full 6,000 strong, was the first to be formed in all of France, and Jean de Siorac enlisted when the king promised to consider a pardon for the murder he had committed. Indeed, when François I inspected the regiment in May 1535, he was so happy that he granted my father’s immediate pardon on condition that he serve five years in the army. “And so,” as Jean de Siorac tells it, “it came to pass that, having learnt the art of healing my fellow men, I had taken up the trade of killing them.”

My grandfather Charles was not a little chagrined to see his younger son recruited as a legionnaire after having spent so many écus to educate him to be a doctor in the town. His sorrow was compounded by his elder son Henry’s behaviour. The future apothecary neglected his studies for drinking and merrymaking, and ended up in the Seine one night drowned (with a little help, evidently, since his pockets had first been carefully emptied).

My grandfather was greatly relieved that the daughter he had always called a “silly gossip”, but who was not lacking in common sense, furnished him with a son-in-law capable of inheriting his shop. ’Tis strange indeed that his apothecary’s shop was passed on for the second time not from father to son, but from father-in-law to son-in-law.

As for my father, Jean de Siorac, he was cast of a very different metal from his elder brother. He set about bravely advancing his fortunes in the legion. He was courageous, patient and tolerant, and, though he never breathed a word of his medical training (for fear of ending up in the medical corps, a role he would have disdained), he treated and bandaged his companions’ wounds, which earned him the goodwill of his commanders and comrades alike.

In all, he served not five, but nine years in the legion, from 1536 to 1545, and in each campaign received a wound and a promotion. From centurion he rose to standard-bearer and from this rank to lieutenant. From lieutenant, in 1544, having been stabbed or shot in every part of his body but the vital ones, he was promoted to captain.

This rank was as high as any enlisted man could aspire to and meant the command of 1,000 legionnaires, pay of 100 livres during each month of a campaign and the lion’s share of any booty pillaged from captured towns. It turned out to be an even greater privilege for my father, for it eventually led to his ennoblement as écuyer, or squire—justly and honourably won by valour rather than by wealth or advantageous marriage vows.

The day my father was named captain, they also promoted his friend and steadfast companion, Jean de Sauveterre. Between these two were woven, out of the hazards of battle and their many brushes with death from which each had saved the other, the ties of an affection so deep that neither time, misfortune nor even my father’s marriage could damage it in the slightest. Jean de Sauveterre was about five years older than my father and was as swarthy as my father was blond, with brown eyes, a badly scarred face and a most reticent tongue.

My father didn’t remain an écuyer for very long. In 1545, he fought so valiantly at Ceresole that he was knighted on the battlefield by his commander, the Duc d’Enghien. My father’s joy was severely compromised, however, by the news that Jean de Sauveterre had received a leg wound so grave as to cause him to limp for the rest of his days. With the return of peace, the best Jean de Sauveterre could look forward to would be some stationary post in a fortress that would have separated him from the other Jean—a thought as unbearable to the one as to the other.

They were plunged in gloomy ruminations about their future when news reached them of the death of my grandfather Charles. He’d scarcely had time to enjoy all the attention his younger son’s military successes had brought to the family. He had been announcing to all his friends in Rouen the upcoming visit of his son, the “Chevalier de Siorac”, when he was overcome with a terrible intestinal pain—a miserere, or appendicitis, according to what I heard. He died, sweating and in terrible pain, before he could see his son, his sole surviving male heir and the only one of his children he had ever really loved, since, as I have said, he considered his daughters worthless.

Jean, Chevalier de Siorac, collected his part of the inheritance, which amounted to 7,537 livres, and, upon his return to camp, sequestered himself in his tent with Jean de Sauveterre to do their accounts. Since both had been careful with their expenses, addicted neither to wine nor to gambling, they had managed to save most of their pay and the greater part of their booty. Moreover, having entrusted the greater part of their savings to an honest Jew in Rouen, each had prospered through his usury and now found that together they possessed some 35,000 livres—a sum large enough to permit them to purchase a farm together, from which they agreed to share all profits and losses.

With the reluctant permission of the lieutenant general, the two Jeans left the Norman legion, taking with them their arms, their horses, their booty and three good foot soldiers in their service. One of these drove a cart bearing all their worldly goods, including an assortment of loaded pistols, blunderbusses and firearms confiscated from their enemies. From Normandy to Périgord, the roads were long and dangerous, and the small troop rode prudently, avoiding large groups of horsemen and cutting to pieces the petty thieves who dared demand payment for bridge crossings. After each band of these scoundrels was dispatched, they were relieved of arms and treasure, a part of the booty going to each of the three soldiers and the rest into the coffers of the two leaders.

On the road to Bergerac, just beyond Bordeaux, their troop overtook a gentle covey of nuns, each on her pony, preceded by a proud abbess in a carriage. At the sight of these five tanned, well-armed and bearded soldiers bearing down on them from the dusty road behind, the nuns began shrieking, thinking, perhaps, to have reached the end of their vows. But Jean de Siorac, riding up alongside the carriage, greeted the abbess with great civility, presented his respects and reassured her of their good intentions. She turned out to be a young woman of noble birth, far from diffident, whose sweetly fluttering eyelashes held out a certain promise, and who asked for escort as far as Sarlat. Now, my father was by reputation easy prey for all the enchantresses of this world, even those in nun’s clothing, and was just about to agree when Jean de Sauveterre intervened. Polite, but stern, fixing his black eyes on the abbess, he pointed out that, at the rate the ponies were going, an escort would necessarily slow down their troop and expose them to many dangers of the road. In short, it was a service that couldn’t be enjoyed for less than fifty livres. Abandoning her charms, the abbess haggled bitterly over this price, but Jean de Sauveterre stood his ground, and she ended up paying this sum right down to the last sol—and in advance.

I remember hearing this story told more than a hundred times when I was still a child, by Cabusse, one of our three soldiers (the other two were known as Marsal and Coulondre). And even though I loved this tale, I found it hard to understand the humour of Cabusse’s closing words, inevitably accompanied by a great belly laugh: “One Jean handled the money and the other Jean handled the rest, God bless ’im!”

At Taniès, my great-grandfather, old François Siorac, had died, and Raymond, Charles’s elder brother, had taken over the land. He received his nephew hospitably, though he was secretly terrified at the sight of five booted, bearded and well-armed men invading his house. But Jean paid his way, both room and board, and, since it was harvest time, the three soldiers rolled up their sleeves and pitched in. They were brave lads and though they served in the Norman legion, two of the three were natives of Quercy and the third—Cabusse—was Gascon.

Before deciding where or how to establish themselves, the two Jeans, astride their best horses and clad in their finest costumes, went from chateau to chateau to present their respects to the Sarlat nobility. Jean de Siorac was then twenty-nine, and with his blue eyes, blond hair and military bearing, he appeared to be in the bloom of his youth, but for a swipe on his left cheek which had scarred but not disfigured him—the rest of his wounds being hidden beneath his clothing. Jean de Sauveterre, at thirty-four, seemed almost old enough to be Siorac’s father, as much because of his already greying, stiffly combed hair and deep-set, jet-black eyes as because of his battle-scarred face. He limped, yet was still nimble, and his large shoulders suggested his great strength.

Neither the Chevalier de Siorac nor Jean de Sauveterre, Écuyer, took the trouble to hide their lowly origins, believing there was no disgrace in being so recently ennobled. Their openness on this matter was the surest sign of their sense of self-worth. Moreover, both men were eloquent speakers, without any trace of haughtiness, yet clearly not men to be lightly dismissed.

The natives of Périgord have the reputation of being amiable, and the two captains were well received wherever they went. Nowhere was their welcome warmer than from the family of François de Caumont, lord of Castelnau and Milandes. The magnificent Château de Castelnau, built by François de Caumont’s grandfather, was then hardly fifty years old, and its Périgord stone still retained its ochre brilliance, especially in the sunlight.

Powerfully situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the entire Dordogne river basin, flanked by a broad circular tower, it seemed to the two captains as if it were impregnable—except perhaps by artillery, which, however, would be disadvantaged by having to fire from so far below its walls. They were also impressed, as they crossed the drawbridge, by two small cannon, set in embrasures, whose crossfire would seriously hinder the advance of any assailant. The two visitors began by complimenting Caumont warmly on this splendid, nearly impregnable castle, which so dominated the Dordogne valley. After these lengthy opening remarks (my father was not given to abbreviating formalities), there was a fulsome exchange of compliments.

François de Caumont had already learnt of his guests’ exploits, and congratulated them on their courage in the service of the king. All of this had to be expressed in the pompous style practised by our fathers’ generation, which I personally find tiring, and prefer the simpler language of our peasants.

François de Caumont (whose brother Geoffroy was to share some hair-raising experiences with me which we survived only by the greatest miracle) was small but powerfully built, with a deep voice and a bright and attentive expression. At twenty-five, he seemed to have the wisdom of a much older man, always inclined to weigh his options, inevitably wary and ready to retreat at the slightest sign of danger. After the ritual exchange of greetings, François sensed in his two visitors a pair of allies open to “the new opinion” of Protestantism, and sounded them out with a few delicate questions. Despite their prudent answers, François’s suspicions proved to be well founded. He knew, of course, the enormous weight such men would lend to his party and immediately resolved to help us to get established in the region.

“Messieurs,” said he, “you couldn’t have come to a better place. In a week’s time, the castlery of Mespech will be auctioned by sealed bids. As you will see, the place has fallen into disrepair since the death of its owner, but its lands are spacious and fertile and include some good grazing land and handsome hardwood forests. The Baron de Fontenac, whose lands abut on the Mespech domain, would naturally like to round out his holdings as cheaply as possible, and he has done everything he can to delay the sale in hopes that the castle will fall into such disrepair that no other buyers would be tempted. However, despite the manoeuvrings of Fontenac, the authorities in Sarlat have finally decided in the interests of the heirs of Mespech to proceed to a sale. The auction will take place on Monday next at noon.”

“Monsieur de Caumont,” said Jean de Sauveterre, “do you count the Baron de Fontenac among your friends?”

“Absolutely not,” answered Caumont. “No one here counts Fontenac as his friend, and he is friend to no man.”

From the silence that followed, Sauveterre understood that there was a long history behind his words that Caumont preferred not to relate. Siorac would have pressed the matter, but at that very moment a gracious maiden entered the great hall, clothed in a very low-cut morning dress, her blonde hair falling freely about her shoulders. Since the beginning of his visits to the noble families of Sarlat, Siorac had seen a great many women whose necks were so bound in plaits and ruffles that their heads appeared to be served on platters. His heart gave a mighty leap at the sight of this white breast sculpted with the grace of a swan, while, for her part, the maiden returned his gaze with her large blue eyes. As he limped forward to exchange greetings with her, Sauveterre caught sight of a medallion on her breast which displeased him mightily.

“Isabelle,” Caumont announced in his deep bass voice, “is the daughter of my uncle, the Chevalier de Caumont. My wife is forced to keep to her bed as a result of the vapours, otherwise she would herself have come down to honour our guests with her presence. But Isabelle will take her place. Although she is not without her own fortune, my cousin Isabelle lodges with us—a distinct honour and a pleasure, for she is perfection itself.” This last was directed, accompanied by a significant look, at Siorac.

François added, jokingly, this time glancing at Sauveterre, “Really there is nothing one could reproach her for, except perhaps her strange taste in medallions.”

Sparks flew from Isabelle’s blue eyes as she replied with a petulant movement of shoulders and neck, “A taste shared, my cousin, by my king, Louis XI—”

“Who was a great king, despite his idolatry,” interrupted Caumont gravely, though his eyes danced in merriment.

When the two Jeans arrived at the Château de Mespech the next morning, they were surprised to find the drawbridge raised. After repeated cries, a hairy head finally appeared on the ramparts, wild-eyed and face flushed with drink: “Go your way!” the fellow croaked. “I have orders to open to no man.”

“What is this order?” asked Jean de Siorac. “And who has given it? I am the Chevalier de Siorac, nephew of Raymond Siorac de Taniès, and I wish to purchase the castlery with my friend and companion, Jean de Sauveterre. How can I make a purchase, my good man, if I cannot visit the premises?”

“Ah, Monsieur,” whined the man, “I humbly beg your pardon, but my life and my family’s lives would be worth nothing if I opened these gates.”

“Who are you and what is your name?”

“Maligou.”

“He seems to like his drink,” muttered Sauveterre.

“Maligou,” said Siorac, “are you a servant in this house?”

“Not on your life,” answered Maligou proudly. “I have lands, a house and a vineyard.”

“A large vineyard?” asked Sauveterre.

“Large enough, Monsieur, for my thirst.”

“And how do you come to be here?”

“My harvest is in, and I agreed, for my misfortune, to serve as guard at Mespech for the heirs of the estate, for two sols a day.”

“You seem to be earning them badly if you don’t open the doors to prospective buyers!”

“Monsieur, I cannot,” said old Maligou plaintively. “I have my orders. And I risk my life if I disobey them.”

“Who gives these orders?”

“You know very well,” said Maligou, his head hanging.

“Maligou,” answered Sauveterre, knitting his brow, “if you don’t lower the drawbridge, I will ride to Sarlat in search of the king’s lieutenant and his archers! And they will hang you for refusing entry to us.”

“I will certainly open the gates to Monsieur de La Boétie,” Maligou sighed in relief, “but I don’t think he’ll hang me. Go find the lieutenant, Monsieur, before I am killed by the others. I beg you in the name of the Lord and all his saints!”

“The Devil take the saints,” grumbled Sauveterre, “does this fool also wear a medallion to the Virgin?”

“Perhaps, but not in so beautiful and goodly a place,” whispered Siorac. And, out loud, “Come, Sauveterre. Let’s ride to Sarlat! We must hie ourselves all the way back to Sarlat thanks to this fool.”

“Or thanks to those who’ve terrorized him,” countered Sauveterre worriedly, spurring his horse. “My brother, we must consider this bad neighbour we shall likely have, if it’s true that the lands of Fontenac border those of Mespech.”

“But ’tis a beautiful chateau,” replied Siorac, standing full up on his stirrups. “’Tis handsome and newly built. We will have much joy from living in a house so new as this. A pox on the narrow windows of the old fortresses with their blackened, moss-covered walls. Let me live instead in shining stone and with doubled windows which let in the sun!”

“And offer easy entry to our assailants…”

“If need be, we’ll reinforce them on the inside with oak shutters.”

“You’re buying a pig in a poke, brother,” growled Sauveterre. “We haven’t even seen the fields.”

“Today the house. Tomorrow and the day after the land,” cried Siorac.

Anthoine de La Boétie, police lieutenant by authority of the seneschalty of Sarlat and of the domain of Domme, lived opposite the church in Sarlat. He had a beautiful new house, pierced with the double casement windows so admired by my father, who loved all the new ideas, whether in matters of religion, agriculture, military science or medicine. For Jean had continued his diligent study of the medical sciences. I recently found in his impressive library a treatise by Ambroise Paré entitled The Method of Treating Wounds Made by the Blunderbuss and Other Firearms, bought, according to my father’s notation, from a book dealer in Sarlat on 13th July 1545, the year of this business concerning Mespech.

Monsieur de La Boétie was elegantly clad in a silk doublet and sported a carefully groomed moustache and goatee. Seated beside him on a low chair was a lad of about fifteen whose homeliness was offset by brilliant piercing eyes.

“My son, Étienne,” Monsieur de La Boétie announced, not without a touch of pride. “Messieurs,” he continued, “I am entirely aware of the machinations of Fontenac. He wants Mespech and will try to get it by any means—no matter how vile and dirty. I have learnt, though alas I cannot prove it, that a month ago he sent some men by night to scale the walls and dislodge some roofing stones so that water could get in and ruin the flooring, thus depreciating the value of the place. Fontenac has only 15,000 livres and knows that no one hereabouts would lend him a sol. So, unless he’s the only bidder on Mespech, he won’t be able to afford it. To prevent any further damage, the heirs to Mespech hired Maligou to stand guard, but Fontenac, having learnt of your interest—”

“So, he knows about us!” said Siorac.

“Like everyone else in Sarlat,” smiled La Boétie, stroking his goatee. “You’re the talk of every chateau and farm in the region. And everyone knows that Fontenac has threatened to roast Maligou and his wife and children alive in their house if he lets you in.”

“And Fontenac is capable of such a thing?” asked Sauveterre.

“He has done much worse,” replied La Boétie with a helpless gesture. “But he’s as clever as a snake and has never left a trace of his foul play by which we could try him.”

“We have some experience of war and command three good soldiers,” said Sauveterre. “Lieutenant, what harm can this brigand baron do to us?”

“Post masked men in ambush on any wooded road in Périgord and attribute your deaths to the many armed bands that infest the countryside.”

“And how many swords does Fontenac have at his disposal?”

“About ten good-for-nothing scoundrels whom he calls his soldiers.”

“Ten?” sniffed Siorac haughtily. “That’s precious few.”

The moment of silence that followed this remark was broken by Anthoine de La Boétie: “But Fontenac has already begun a campaign of rumours to get at you by subtler means. The monster possesses a kind of venomous sweetness to sugar his plots. He has already advised the bishopric of Sarlat that you are both purported to be members of the reformed religion.”

“We are neither of us members of the reformed congregation,” replied Siorac after a moment of reflection, “and we attend Mass like everyone else.”

Sauveterre neither confirmed nor denied this, but chose to remain silent. This difference did not go unnoticed by Anthoine de La Boétie. As for his son, Étienne, he rose, walked briskly to the window and turned, saying with equal indignation and eloquence, “Is it not shameful to question these gentlemen’s attendance at Mass when they have shed their blood for ten years in the service of the kingdom? And who dares raise this question? This incendiary, this butcher, this wild animal, this dirty plague of a man who wears religion like a shield to cover his crimes! God preserve us from the worst tyranny of all which respects not our beliefs—”

“My son,” broke in Anthoine with a mixture of affection and admiration, “I appreciate the feelings which incite your generous heart against oppression.”

“Moreover, you express yourself admirably,” said Siorac to Étienne. It had not escaped his notice that Étienne had said “in the service of the kingdom” and not “in the service of the king”.

Étienne returned to his place on the stool beside Monsieur de La Boétie’s chair and, blushing, took Anthoine’s hand in a touching gesture that revealed his love for his father. His ardent look conveyed his immense gratitude for the approbation he had received. What good fortune that nature had united such a father and son, for their hearts could not be closer nor their wills more clearly intermingled.

“Ah, Father,” exclaimed Étienne, tears in his eyes, “why do people accept tyranny so easily? I think about this every day God has given me to live. I cannot forget the infernal expedition undertaken last April against the poor Vaudois people of Luberon: 800 workers massacred, their villages burnt, their wives and daughters raped in the very church of Mérindol and then burnt inside, the old women who instead of being raped were torn asunder by gunpowder forced into their intimate parts, prisoners who were eviscerated alive to have their guts displayed on sticks! And the Pope’s legate, witnessing these horrors at Cabrières, applauded them! And why did all this happen? Because these poor people, peaceful and hard-working as they are, refused to hear Mass, worship the saints and accept confession—just like the reformists whom they resemble so closely. As you know, Father, I am as good a Catholic as the next man (though I cannot approve of the corruption of the Roman Church), but I blush for shame that the Church of St Peter has steered the king of France towards such abominations…”

“My son,” said Anthoine de La Boétie, glancing with embarrassment at his guests, “you know as I do that our king, François I, is a good man. He signed without reading them the letters ordering the Baron d’Oppède to execute the Act of the parliament at Aix against the Vaudois. But afterwards he was filled with such remorse that he has ordered an inquest against the men responsible for these massacres.”

“Alas, it is too late now!” replied Étienne. But sensing his father’s impatience, he sighed, lowered his eyes and fell silent.

Sauveterre broke the silence: “If I may return to this rascal Fontenac, may I ask if his word has any weight with the bishop?”

“I know not,” replied La Boétie, who looked as if he knew all too well. “This scoundrel claims to be a good Catholic, although he’s a miserable excuse for a Christian. He pays for Masses, and makes many charitable contributions…”

“And the bishop accepts these payments?”

“Well, the problem is that we don’t have a bishop,” rejoined La Boétie with a smile, all the while stroking his goatee with the back of his hand. “Our bishop, Nicolas de Gadis, appointed by Catherine de’ Medici, is a Florentine, like his patroness, and lives in Rome where he awaits his cardinal’s mitre.”

“In Rome!” replied Siorac. “The tithes extracted from the sweat of the Sarlat workers have a long way to go to reach him!” At this exclamation, Étienne burst out laughing, and his sudden gaiety infused his melancholy countenance with youth.

“We have, of course, a coadjutor,” La Boétie added, half seriously, half amusedly, “one Jean Fabri.”

“But he lives in Belvès,” noted Étienne, “since he finds the climate of Sarlat suffocating, especially in summer…”

“From Sarlat to Belvès,” Siorac rejoined in the spirit of the moment, “the Church tithes have less far to travel than to Rome.”

“But a few of these tithes must tarry in Sarlat,” said Étienne, “for we have here a tertium quid, the vicar general, Noailles, who pretends to govern in their place.”

This exchange had the effect of weaving a close complicity among these four men, barely masked by the apparent hilarity of their speech. La Boétie rose; as Étienne stood up, his father put his arm around his son’s shoulders and, smiling, looked at his visitors as they rose too—Sauveterre with some difficulty due to his infirm leg.

“Gentlemen, if you want Mespech,” he continued in that inimitable Périgordian jocular manner, which always masks some more serious or satirical intention, “you’ll have to make some concessions. It may be too much to ask of you to make a gift to Anthoine de Noailles in honour of the Holy Virgin, for whom you have so long felt a special devotion…”

Siorac smiled but refrained from any response; Sauveterre remained impassive.

“Or perhaps you could manage to attend High Mass this Sunday at Sarlat. The vicar general will be presiding and could not fail to notice your presence.”

“Indeed!” cried Siorac happily. “If Mespech is to our liking, we will not fail to be there!”

The king’s lieutenant and his archers, followed by the two Jeans, had only to appear; the drawbridge of Mespech was lowered before them. Maligou, infinitely relieved to escape with a scolding, was sent home and four of La Boétie’s men were stationed within the walls until the date of the sale. La Boétie obviously feared that a desperate Fontenac might try to set fire to the place, since, without the chateau itself, the vast acreage of Mespech would attract no buyer other than its powerful neighbour.

After La Boétie had taken his leave, Siorac and Sauveterre explored Mespech from top to bottom. The next day, Friday, they spent surveying the farmlands and woods belonging to the property. On Saturday they returned to Sarlat and there, in the presence of Ricou, the notary, they formally adopted each other and ceded each to the other all of his present and future worldly goods. From this moment on, the two Jeans became brothers, not only out of the mutual affection they had sworn, but now legally as well, heirs one of the other—and Mespech, should they acquire it, was to be their indissoluble property.

I have read this moving document. It is composed entirely in langue d’oc even though by this time all official acts were already written in French. But the notaries were the last to give in to this rule, since their clients more often than not could understand nothing of the northern tongue.

Word of the captains’ brothering had spread in Sarlat, and it was quickly bruited about that the two worthies would purchase Mespech right from under Fontenac’s nose. And this hypothesis was confirmed when they were sighted at High Mass the next morning. Rumour also had it that after Mass they presented the vicar general, Anthoine de Noailles, with a gift of 500 livres “for the poor veterans of the king’s armies who live within the diocese in feeble and crippled condition”.

The arrival of the captains in Sarlat, that Sunday, was no trivial event: they passed through the la Lendrevie gate, escorted by their three soldiers, all five (except Coulondre) with pistols and swords drawn and at the ready. They paraded through the streets, Siorac and Sauveterre, eyes on the windows above them, their soldiers scrutinizing every passer-by. They did not sheathe their weapons until they dismounted in front of La Boétie’s house. The lieutenant, alerted by the sound of horses’ hooves in the street, immediately emerged to greet them, smiling and extending a welcoming hand, a gesture intended to impress upon those gathered in the square (as was their custom in good weather before Mass), the consideration accorded these newcomers by a royal officer.

There was a great to-do when the “Brethren” had withdrawn into La Boétie’s house, much chatter and shaking of heads among the burghers, while the peasants crowded around the five purebred steeds tethered by the three soldiers, admiring their sweaty flanks and the military fittings, whose embroidered covers had been folded back to reveal the handles of their powerful firearms.

Fontenac was roundly detested by the burghers of Sarlat, as well as by the nobles in their chateaux, because of his many crimes and infinite excesses, yet the populace of the town favoured him since, with the profits of his various plunders, he occasionally paid for a religious procession supposedly to honour a saint, but which always ended up in a river of free wine and the usual street fight which La Boétie had to quell. Despite these all-too-frequent disruptions, many are of the opinion that the peasants, who must work from dawn to dusk for a pittance, cannot help loving the Church processions, since they provide a day of rest—the innumerable saints revered by the Catholic cult providing fifty holidays, not counting Sundays, year in, year out. Thus it has always been easy to excite the populace against members of the reformed religion because they are suspected of wanting to do away with these holidays by suppressing the worship of the very saints which occasion them.

Although the dialects of Quercy and Gascony are quite different from their own, these gawkers soon discovered that our soldiers spoke the langue d’oc. And so, as they patted the horses, admiring the saddles and the iron hook Coulondre wore in place of his left hand, they rattled off innumerable questions which only Cabusse, with his quick wit and ready tongue, seemed inclined to answer.

“Are your masters going to purchase Mespech?”

“We don’t have masters. These gentlemen are our captains.”

“Are your captains going to purchase the chateau?”

“Perhaps.”

“Can they afford it?”

“I haven’t inspected their coffers.”

“It’s rumoured that Fontenac has 15,000 livres.”

“May God keep them for him.”

“Do your captains have more?”

“You’ll have to ask them.”

“Suppose your captains do acquire Mespech. We hear that Monsieur de Fontenac won’t stomach such an insult.”

“May God preserve his digestion.”

“You swear by God. Do you also swear by His saints?”

“Indeed so, by the saint of gawkers!”

“What religion are you?”

“The same as you.”

“They say your captains are afflicted with the scourge of heresy.”

“Only a fool would say such a thing.”

Whereupon Cabusse rose up and shouted at the top of his lungs, “Good people, get out from under our horses’ hooves and take your hands off our saddles!” And such is the authority of a large man with a loud voice that he was immediately obeyed.

As soon as the door closed behind La Boétie and his guests, the police lieutenant announced: “Gentlemen, I have just learnt from a spy that Fontenac intends to ambush you tonight at Taniès. If you wish, I will give you and your men lodging in my country house tonight and until the sale is completed.”

“I thank you infinitely for your offer, Monsieur de La Boétie,” replied Siorac, “but we cannot accept it. If Fontenac did not find us at Taniès, God knows what evil vengeance he would wreak on my uncle’s family and their poor villagers!”

“Siorac is right,” said Sauveterre, seemingly unperturbed by the fact that Siorac had spoken before consulting him. He added, “Thanks to you, Lieutenant, the surprise will not be ours tonight, but Fontenac’s.”

“Oh, he won’t be there,” cautioned La Boétie. “He’s too clever for that.”

“But if we eliminate his band,” countered Siorac, “we’ll dull his fangs a bit.”

Taniès, home to about ten families whose houses cluster around a squat church tower, is built on a hill from which a steep road descends to the banks of the les Beunes river. Now, the river gets its plural name by reason of the canals and millraces which seem to double its course. The name also designates the little valley watered by this river as far as the village of Ayzies. A fairly well-paved road runs the length of this river—the only means of access to the Château de Fontenac.

At dusk, our captains posted Cabusse and Uncle Siorac’s two sons at the foot of this hill, for they figured that their assailants would probably tether their horses there and creep on foot up the steepest and rockiest face of the hill leading to the village. Cabusse and his men were not to engage the enemy, but to let them pass by and, at the first sound of gunfire, to overpower anyone left on guard there and lead the horses to one of my uncle’s barns nearby. This done, they were to return and lie in wait for any of the assailants who might try to flee that way and to shoot them as they reached the bottom of the hill.

Cabusse, who later recounted this adventure (for the Brethren disdained any talk of their own exploits) laughingly told me that the hardest part of the whole affair was not to enter battle but to convince the villagers to join in, so terrified were they of Fontenac. However, once their minds were made up, nothing could stem their fury. After the battle, they coldly put to death all of the wounded and immediately set to stripping them of their clothes and boots, vociferously demanding their share of the plunder, not only arms but horses, despite the fact that it was Raymond Siorac’s two sons who, alone, had participated in their capture.

To each of these lads, the captains gave a horse and saddle, and to the village they presented another two horses to be shared by all in the fields. But the villagers, accustomed to the use of oxen, preferred to sell the horses and divide the money. The Brethren kept the rest, to wit, six handsome and powerful horses, as apt for working in the fields as for saddle riding and which would be useful when the time came to break ground at Mespech.

Without suffering a single casualty, they killed that night six of the outlaw baron’s band. And they took one prisoner: the horse guard, whom Cabusse had knocked unconscious along the les Beunes river. When he was returned to the village, it was extremely difficult to prevent the villagers from tearing him apart. But one prisoner had to be kept alive in order to have someone to bear witness against Fontenac. To judge by the number of horses, two of the assailants must have slipped away on foot in the darkness, despite the full moon. Of course, it must be pointed out that, once past les Beunes, the forest of chestnut trees provides a deep, well-shaded cover for the full five leagues that separate Taniès from Fontenac.

The following Monday, the date of the sale of Mespech, the captains had the bloodied bodies piled in a cart and delivered to La Boétie along with the prisoner. This latter was sequestered in the city jail, but La Boétie displayed the bodies at the gibbet in Sarlat, which stood in those days opposite the la Rigaudie gate. The populace immediately crowded around. The gawkers apparently included several young women, although the six ruffians were stark naked.

La Boétie lingered awhile nearby with the captains, not so much to enjoy the spectacle as to listen to the townspeople and note which of them seemed to recognize friends among the hanged bodies of Fontenac’s men, with whom they had been drinking of late in the taverns of the town. And, indeed, as the winds began to shift against the robber baron, tongues began wagging.

As for the prisoner, the executioner began his inquisition an hour after arriving in Sarlat, and he told all and more than all. Indeed he revealed some well-nigh unbelievable atrocities committed two years previously, which weighed heavily on the conscience of this churl, clearly made of weaker stuff than his master.

In 1543, a rich burgher of Montignac, one Lagarrigue, had disappeared. A month later, his wife left the town alone on horseback never to reappear. The prisoner’s confession shed sinister light on these disappearances. Fontenac had kidnapped Lagarrigue on the way from Montignac to Sarlat at dusk one evening, killing his two servants and sequestering his captive in his chateau. Then, secretly, he alerted the wife to her husband’s plight. And, on condition that she breathe not a word of his whereabouts to a living soul, not even to her confessor, he promised to release the man for a ransom of 8,000 livres. She was to deliver this sum alone, and without anyone’s knowledge.

This unfortunate lady, who nourished an extraordinary love for her husband and who trembled at the thought of losing him, was mad enough to believe the robber baron to be a man of his word. She obeyed him in all particulars. Once the great doors of the chateau had closed upon her, and the ransom money was counted and locked away in his coffers, Fontenac, a man of uncommonly good looks, education and manners, told the lady, in the sweetest of tones, to be patient and that she should soon be reunited with her husband. But no sooner was Lagarrigue dragged before him, bloodied and chained, than Fontenac changed his expression and his tune. He threw the lady down before his servingmen telling them to take their pleasure of her if they were so inclined. And so they did—within plain sight of Lagarrigue, who struggled in his bonds like a madman.

So that nothing should be lacking in the complete torture of the poor woman, he then ordered her husband strangled before her very eyes and threatened her with a similar fate. Still, he kept her alive for two or three days for the amusement of his soldiers. But as several among them expressed pity for her, since she had maintained a Christian composure and dignity throughout her abominable ordeal, Fontenac, as if to provide a lesson in cruelty, plunged his dagger into her heart, turning and twisting the blade, asking her with terrible blasphemies whether he gave her thus her pleasure. The two bodies were then thrown into the dry moat and burnt so that no trace of this horrible crime should survive. And Fontenac, watching from the ramparts above the acrid smoke rising towards him, remarked snidely that Lagarrigue and his lady should be happy that they were now finally reunited.

Fontenac got wind of his henchman’s testimony and did not appear in Sarlat on that Monday at noon. Mespech was sold in broad daylight for 25,000 livres to Jean de Siorac and Jean de Sauveterre, a modest enough price for such a rich and extensive property, but not as low as Fontenac would have paid had he succeeded in his scheme to be the only bidder.

We might think that finally justice was about to be rendered on Fontenac in the form of capital punishment. But the prisoner who accused him died, poisoned in his jail two days later, and his death rendered ever more fragile the testimony brought against the robber baron. The parliament of Bordeaux called Fontenac to testify, but he refused to quit his crenellated hideout. He wrote to the president of the parliament a most courteous and elegant letter of regret, sprinkled, naturally, with erudite Latin phrases.

With profuse compliments, he regretted infinitely his inability to conform to their commandment, beset as he was with a grave malady which had him at death’s very door, praying for recovery. Moreover, he claimed to be the victim of a heinous plot in which the awful hand of heretics could be discerned from beginning to end. While it was true that the six men hanged at Sarlat had been in his service, these villains, driven by shameful promises, had quit his household the previous day, stealing blunderbusses and horses for their dark purposes. They had, he claimed, hoped to sign on in the service of some religionaries, who, hiding their real beliefs, wanted to settle in that province and contaminate it. But as soon as his faithless servants arrived at their rendezvous with these devious and bloodthirsty Huguenots they were treacherously assassinated, both to give the impression that Fontenac had attacked them and to make off with arms and horses rightfully his. As for the prisoner, even if one were able to accept his testimony, since it was unique and unsupported (testis unus, testis nullus—a single witness is of no value), his tongue had obviously been bought by the Huguenots to besmirch the timeless honour of the Fontenac name. If Fontenac had been able to confront this miserable wretch, he surely would have recanted all his lies. But a very suspicious death (fecit qui prodest—he who profits from the crime must be its author) had intervened, ensuring his silence for the evident benefit of his accusers.

In sum, Fontenac demanded that the president of the Bordeaux parliament issue an injunction to Messieurs Siorac and Sauveterre stipulating the immediate return of his arms and his horses. So powerful was the spirit of partisanship in the last years of the reign of François I, and so general was the parliament’s suspicion of any who even appeared to favour the heresy, that this brazen and specious letter from Fontenac shook the resolve of the Bordeaux president and his advisors despite Fontenac’s execrable reputation throughout Guyenne. They immediately convoked not only our two captains, but also La Boétie, the two consuls of Sarlat, and François de Caumont, as delegate of the nobility, to establish the facts of the case. In addition, the parliament refused to hear the case unless the two captains agreed to submit to an interrogation of their beliefs. They consented to this stipulation on condition that their testimony be privately taken by the counsellor assigned to this interrogation.

This counsellor was a thoughtful, grey-haired gentleman of impeccable manners who apologized profusely to the two brothers before beginning his interrogation.

“Good Counsellor,” said Siorac, “how can an accusation coming from such a thorough scoundrel be given any credence whatsoever?”

“Well, he is a good Catholic, however great his sins! He goes to Mass and to confession and takes Communion—he even attends retreats in a convent.”

“What a pity that good works do not follow upon good words.”

“I am happy,” rejoined the counsellor, “to hear you speak of works. In your mind, is it by good works that a Christian can hope for salvation?”

Sauveterre’s look darkened considerably, but Siorac responded without hesitation: “Certainly, that is how I understand the matter.”

“You reassure me, Monsieur,” smiled the counsellor. “But after all, I am not a great clerk and ask only the simplest questions which you can easily answer. Do you yourself regularly attend Mass?”

“Indeed so, Counsellor.”

“Let us not stand on ceremony, I beg you. Do you mind answering simply ‘yes’ or ‘no’?”

“As you wish.”

“I shall continue, then. Do you honour the Holy Virgin and the saints?”

“Yes.”

“Do your prayers invoke the intercession of the Virgin and the saints?”

“Yes.”

“Do you respect the medallions, paintings, stained-glass windows and statues that represent them?”

“Yes.”

“Do you accept spoken confession?”

“Yes.”

“Do you believe in the real presence of God in the Eucharist?”

“Yes.”

“Do you believe in Purgatory?”

“Yes.”

“Do you believe that the Pope is the holy pontiff of the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic Church and that every Christian owes him obedience?”

“Yes.”

“Do you worship the saints and the martyrs?”

“Yes.”

“Next August in Sarlat, will you follow the procession in honour of the Virgin devoutly, bareheaded, candle in hand?”

“Yes.”

The counsellor wanted to turn next to Sauveterre in order to pursue his inquisition, but Sauveterre rose and limped forward, speaking quite firmly and staring him down with his dark eyes: “Counsellor, my brother has responded excellently to all of your questions. Take his replies for my own. And pray conclude that our religion is in every respect the same as that of the king of France, whom we both served faithfully in the legion in Normandy.”

This aggressive parry caught the counsellor quite off guard and he sensed that nothing was to be gained by pursuing the matter further. And yet he was not satisfied. For he was accustomed to the type of men who were drawn to the reformed religion like a nail to a magnet, and from this perspective the very virtues of the captains, their seriousness, knowledge and tranquil courage did not speak in their favour.

“These are honest men to be sure,” the counsellor reported to the president of the parliament at the conclusion of his inquest. “They are free of any frivolity, weakness or faults of any kind. And yet they give lip service to the religion of the king. I detect a Huguenot odour about them.”

“Despite your keen sense of smell,” replied the president, “an odour is not sufficient to convict them. As long as they refrain from professing the plague of reform, they are not rebels against the king. Leave these questions of zeal to churchmen.”

Whatever odour the parliament detected on Baron de Fontenac and whatever support this bandit received from them remained a mystery. “Lacking any material proof or irrefutable testimony”, the parliament ultimately banished him for twenty years from the seneschalty of Sarlat and from the domain of Domme, an act deemed excessively clement throughout Guyenne.

On the way home, La Boétie left the consuls of Sarlat and Caumont at their homes and then set out in advance to prepare lodgings for the little company at Libourne, followed at some distance by the “Brethren”, as they were now popularly called, touchingly joining them in a single noun as if they were one and the same person.

“What a pity we are in such haste,” remarked La Boétie, “for otherwise we might have passed through Montaigne, and I could have introduced you to a funny little twelve-year-old who has learnt Latin from his father, and amazes everyone with his readings from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.”

“This gentleman,” said Siorac, “does very well to take the trouble to instruct his son. We badly need knowledgeable men to lead us out of our barbarism.”

“Alas, knowledge and morality are not always sisters,” lamented La Boétie. “Fontenac is well enough educated.”

“And the scoundrel used his letters well enough,” cried Sauveterre. “Twenty years of banishment for so many murders! My blood boils at such evil.”

“And he has only killed ten people,” rejoined La Boétie. “What should we do with the Baron d’Oppède, who has massacred the peasants of Luberon by the hundred, confiscated their lands in the name of the king and then secretly purchased them himself? He is on trial now, but you can rest assured he’ll emerge from it all as white as the new-fallen snow.”

“So it is in our sad world,” said Sauveterre, “ceaselessly dragged through blood and mire, and through the mendacious superstitions that have corrupted the pure Word of God.”

A silence followed these words. No one, not even Siorac, felt like picking up on Sauveterre’s lead, least of all La Boétie.

“And who will occupy the barony of Fontenac for these twenty years of banishment?” asked Siorac.

“The baron’s only son, Bertrand de Fontenac, who has just turned fifteen and is now of age.” And La Boétie added after a moment’s reflection: “Now you are rid of the old wolf, my friends, but there’s still the cub. I have heard little good concerning this fellow, and since he’s young, he may yet grow sharp teeth.”

2

IWAS BORN on 28th March 1551, six years after the acquisition of Mespech by the Brethren, when its appearance had already considerably changed. Actually the captains made few changes in the chateau itself: it was a huge rectangular construction of two stories built around an interior courtyard and flanked at each corner by towers with machicolations, and these were joined by a crenellated battlement walk.

When they bought it, however, the chateau was surrounded only by an embryonic moat, scarcely a toise wide and so shallow that a small person, if thrown in, could easily regain his footing. Obviously, this was a ridiculous defence. Such a moat rendered the drawbridge leading to the chateau’s fortified south gate totally superfluous. Any attacker could have easily waded across the moat and thrown up a ladder against the ramparts, anchoring it in the mud at the foot of the wall.

The technology and inventiveness that the captains dedicated to their modifications of these moats could not have succeeded without one lucky circumstance: the well dug in a corner of the interior courtyard at Mespech turned out to be inexhaustible. The Brethren discovered this when, a short time after the sale, they set about emptying the well to purify it. In the middle of August, during a severe drought, they began work in pairs with buckets, but since the water level remained constant, and the well’s circumference permitted it, the work crew expanded to three, to four, then five… At eight men strong, the level began to recede somewhat, and they redoubled their efforts. Ultimately the level was lowered enough to reveal a split in the bedrock the size of a fist, through which water gushed in a steady stream. The captains sounded a retreat before this friendly assault and the water quickly rose to its usual level and gushed into the conduit which empties into the moat.