7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

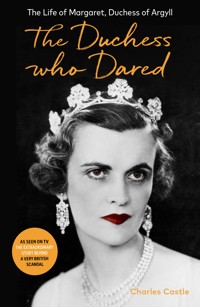

The extraordinary story behind A Very British Scandal, starring Claire Foy and Paul Bettany ?Margaret was debutante of the year, the beautiful fairy-tale heiress immortalised in Cole Porter's 'You're The Top' - who ended up penniless and ostracised from her own family. Legal actions coloured her life - her divorce from the Duke of Argyll was one of the longest, costliest and most notorious in British legal history. Her diaries, and photographs of her with an anonymous naked man, were used in evidence. This sparkling biography draws on exclusive interviews with the late Duchess to lift the lid off her extraordinary story, and her scandalous lifestyle. The Duchess Who Dared is a fascinating chronicle of a complex, charming and surprisingly modern woman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Foreword1 · The Bad Seed2 · Dance, Little Lady3 · Cupid and the Concierge4 · The Campbells Are Coming5 · Trouble Ahead6 · Dark December7 · Into the Breach8 · The Divorce Hearing9 · Call It Living in Sin10 · Friends, Family and Foes11 · Good Causes12 · The Beginning of the EndForeword

Margaret Whigham, Scots-born socialite and heiress, was an enchantress, considered one of the most beautiful women of her generation and one of the ten best-dressed in the world. Charming, elegant and gregarious, she was as sought after, reported and photographed in the press as a Hollywood film star. Much travelled, she revolutionized the public’s previous perception of débutantes in the thirties and took London by storm – then and for many years to come. There seemed few in the political, social, theatrical or movie worlds who either did not know her or who did not wish to make her acquaintance. Some to their detriment.

Her first marriage to the American businessman and golfer Charles Sweeny ended in divorce, but the match produced two children: their daughter became Duchess of Rutland shortly after coming out, and their son a businessman in investments, like his father.

Although Margaret’s second marriage, to the Duke of Argyll, lasted only ten years, her divorce from him was the longest, costliest and most scandalous in British divorce history. She paid a phenomenal price when the Duke finally won his freedom. She was also involved in at least seven legal actions running concurrently concerning poison-pen letters, a paternity suit (in which she was threatened with contempt and possible imprisonment), and others relating to libel and slander.

Margaret, Duchess of Argyll, asked me to write her life story over twenty years ago. We first met at the home in New York of our mutual American lawyer Arnold Weissberger during a party to celebrate the publication of my biography Noël, based on my television film about the life of Sir Noël Coward. A few months later Margaret telephoned me: she had read my book and was also impressed with the television documentary I had made on the departure of the Duke and Duchess of Bedford from Woburn Abbey. I agreed to her idea on condition that on each occasion we met I could bring a tape recorder to achieve a verbatim account of her story and so that I could report her speech patterns and expressions accurately. Also I needed both copyright and legal protection against any unforeseeable litigation – I was all too aware that her past had been bound up with treachery, adultery and deceit.

I arrived for dinner one evening in 1974 at her Queen Anne house, 48 Upper Grosvenor Street, opposite the American ssy in London’s Mayfair. The drawing room, where Margaret was waiting for me, and library were products of the design of Mrs Somerset (Syrie) Maugham, who made popular the ‘white on white’ décor that became fashionable for salons in London, Paris and New York. Margaret stood at the end of the room, her face to the light, conscious of the effect her appearance would have on me. She had large expressive green eyes and dark auburn hair swept up from her face, arranged daily by the Mayfair society hairdresser Renée. Her carefully applied make-up was immaculate, touched up constantly during dinner and conversation. She had the fine pure white porcelain skin of a woman who had never been exposed to the sun or sullied by liquor: she hardly drank except, perhaps, for a glass of wine at dinner. Her lips were painted bright red, reminding me of the make-up of the thirties when she was at the height of her beauty, and matched perfectly the varnish on the immaculately manicured nails that tipped long, tapered fingers on hands that had never done a day’s work. Lean shapely legs, fine ankles and delicate size-three feet were enhanced by smoky grey silk stockings, and her elegant black satin shoes were decorated with diamanté clips. She wore a black silk dress with dark chiffon covering her chest and long, slender arms. Three rows of perfectly matched pearls adorned her neck, fastened with a diamond clasp.

Her staff consisted of a butler, who opened the street door to those courageous enough to venture inside and waited at table with royal aplomb although he was seldom sober, and a maid who was rarely visible since her time was spent in her mistress’s boudoir tending exquisite garments by Molyneux and Hartnell and custom-made silk underwear. The cook, Mrs Duckworth, produced simple but good English fare in tiny portions, at which Margaret would pick indifferently. Margaret could boil neither an egg nor water and had never made her own bed.

I followed Margaret into the panelled library across the first-floor landing, and became impressed by her upright stature and her lengthy assertive strides. She reminded me of a quality thoroughbred I had seen at Tattersalls. The two poodles, Marcel and Alphonse, were close at her heels then and were always with her during my visits. We sat opposite one another in low, upholstered chairs on either side of the small elegant sofa on which the poodles pounced. I noticed two electric push-buttons set into the wall within easy reach of her right hand. The small household one summoned the butler, who appeared equipped with the dogs’ bowls on a salver. The larger button was connected with the West End police station as well as Fleet Street; she was anxious about protection, having had burglaries and strings of unwanted callers in the past – many of them bearing writs – and, as a rich woman living alone, she was aware of the publicity that any intruder or assailant might bring. Her dependency on such stringent security measures was strangely discomforting and I often found myself staring at the close proximity of her right hand to the buttons.

She was poised and her voice had a soft, sexy, mellifluous timbre, the Mayfair vowels betraying none of her Scottish or American background. She also spoke with a pronounced stammer. As a child she had been sent to speech therapists, who discovered that the reason for this was psychological, due to nervousness caused by insecurity. Throughout our meetings, however, she stammered little: our exchanges were relaxed and friendly.

On my first call she gave a brief summary of her life’s pattern and later went into finer detail, illustrating and substantiating her stories with a collection of scrapbooks, immaculately kept in a large cupboard behind her chair. She had a copy of every news-cutting about her chequered life, sent from all corners of the globe. Each volume was bound in bright red leather, and on the gold-engraved spine was the letter ‘M’ with a coronet above it. Asked why she kept this library of her life so intact she explained that it was for the benefit of her grandchildren: she wanted them to know the truth about her past. I noticed, however, that certain cuttings were missing concerning the Duke of Argyll’s children from his former marriage. They had become the subject of a monumental scandal which led to Margaret’s downfall.

When I switched on the tape recorder on 16 April 1974 she began to recall the unbelievable story of her life, revealing details she had previously kept secret. Her first words were careful and hesitant because of her stammer. She said much, perhaps unwisely, as she had been restrained from uttering certain slanders by a court order and could have landed in prison were she to repeat them.

Margaret always wanted to dance with me. Her first husband Charles Sweeny danced like Astaire. She knew that I had been a professional stage and television dancer after the style of Gene Kelly and that I liked dancing. Despite my caution, three months later, she proved how deceitful she really was and I became another victim of the lies for which she was so well known. It was often difficult to discern when she was lying or telling the truth. I believe that she, herself, was sometimes confused about what was fact and what fantasy.

It all proved fascinating listening although much of what she told me could not be published for libel reasons. Margaret’s vitriolic remarks about people in high office whom she knew illustrated the sort of woman she was.

For all that, her story was compelling, and she told it in words evocative of the thirties, the period of her fame. Her speech patterns and phraseology brought her past to life – even if her account was unreliable. She had, after all, been branded a poisonous liar in court.

Margaret always wanted to be a star, and she became one – a star of courtrooms and tabloids. Her role was always that of the heroine and she made everyone else seem the villain.

Margaret might have been a woman of straw, but you couldn’t help liking her: she was elegant, poised, well dressed and had impeccable manners in society. She enjoyed being addressed as ‘Your Grace’ by lesser folk, had no respect for people and less for the law. She could be rude, off-handed and insulting to those who served her. The stories told against her by beauticians, vendeuses, restaurant waiters and hotel staff are legion. When once asked by a journalist: ‘Do you enjoy being a Duchess?’, she replied without hesitation: ‘Who doesn’t?’

—Charles Castle

Chapter One

The Bad Seed

‘God knows he was an old bastard,’ said the Duchess. She was referring to the High Court judge who had awarded her husband a divorce on the grounds of her adultery, and who had concluded that ‘The Duchess is wholly immoral.’ He also recorded that she was promiscuous. She had been branded a liar by Queen’s Counsel at a previous trial and her husband had referred to her as ‘S’ – Satan.

The Duke named three men as co-respondents in his action against her and Margaret counter-petitioned against him in vain. Stories had circulated in London that she kept pornographic diaries in which she awarded her lovers star ratings based on their sexual abilities. It was proved that she had indecent photographs of herself with other men, taken during her marriage to the Duke, which he seized from her at night while she was asleep. In summing up, the judge, Lord Wheatley, took four and a half hours to deliver 64,000 words. ‘The photographs not only establish that the Duchess was carrying on an adulterous association with an unknown man or men but they also reveal that the Duchess is a highly sexed woman who had ceased to be satisfied with normal relations and had started to indulge in what I can only describe as disgusting sexual activities to gratify her sexual appetite.’

The woman who became the Duchess of Argyll had loved the man she married in 1951 but love turned to hate on both sides after four embittered years. She believed that the husband who had once cherished her finally tricked, attacked and humiliated her. But he did so for several good reasons. She believed that there was a dirty-tricks campaign to drive her out of society after she had married the Duke. She was also aware that it was a dirty, treacherous and lengthy tangle with the truth. Yet it was she alone who was the instigator of the poison-pen letters, slanders and intrigue wrought on the name of the Argyll family that led to the many legal actions that ensued. Margaret entered into the foray with relish. She knew it would lead to endless time taken up with lawyers and counsel, with private detectives whom she employed to trail some of her enemies and others who shadowed her and bugged her hired car in New York, incurring costs that would have crippled Fort Knox. Something in her nature drove her on without fear to do precisely what she wanted no matter the price or the consequence.

Margaret Whigham was born in Scotland on 1 December 1912. She was described in the press as the greatest débutante of all time before she reached the age of eighteen and by the thirties was a celebrated beauty. The tide turned on the fashionable and successful party-goer when her first marriage to the handsome John Kennedy look-alike and much sought-after London-based Irish-American Charles Sweeny ended in divorce.

As the only child of millionaire parents who provided her with comfort, shielded her from the realities of life and lavished limitless money on her she grew up to possess not only enviable beauty and grace, but every conceivable material advantage.

Yet Margaret’s girlhood was an empty shell. She had no friends with whom to play and laugh, share jokes or to invent stories. There was no sharing of any kind, of either toys or emotions. Like a parrot in a gilded cage, she chirped away but attracted no loving response except admiration and pride of possession. She was fed and provided for, but she was never taught to love, and never learnt the importance and satisfaction of true and honest emotion. She was never taught respect for anyone outside her family.

‘My father George Hay Whigham was one of ten children,’ Margaret, Duchess of Argyll began. ‘His father, David Dundas Whigham, was a Scots county squire of considerable charm, but the possessor of very little money. He was, however, a proud man determined that his sons would do well, which indeed they did.

‘Father’s eldest brother Robert became General on Foch’s staff in the first war and was subsequently knighted. Four of my uncles became millionaires including my father. Jim, the second eldest, although he never made a great deal of money, had an interesting life as a roving reporter and finally became editor of the American magazine Town and Country. The other three were Charles, a partner of Morgan Grenfell, one of the great financing houses in England and America, who helped to negotiate the Anglo-American loan after the First World War; Gilbert, head of the Burmah Oil Company; and Walter, Director of the Bank of England, the richest of them all. My father George founded and became chairman of the multi-million-pound Celanese man-made fibre empire after helping to build the Canadian Pacific and Cuban Railways under Sir William van Horen.’

Margaret’s family were all true-blue God-fearing Presbyterians. On her father’s side the line goes back to the twelfth century when Helias de Dundas was granted the lands of Dundas in Scotland by King David I. The Dundas men remained prominent down the centuries, one as judge of the Court of Session in 1662, then his son Sir Robert Dundas, who rose to the bench, and his grandson who became Solicitor-General for Scotland. (Perhaps it is no wonder that Margaret became so enmeshed in the law since it had been in the family’s blood for so long.) The next generation produced another Robert, who became Lord Advocate and then Lord President. Born on 22 August 1832, Margaret’s grandfather, David Dundas Whigham, came of the ancient Scottish legal line from Dumfriesshire near Glasgow. He was the immediate founder of Margaret’s family and son of Robert Whigham of Lochpatrick, an advocate and Sheriff of Perthshire, who married the only daughter of Sir Robert Dundas in 1824, Jane. He was an exacting man with cast-iron determination and his sons knew they would have much to answer for if they should fail to make a success of their lives.

Margaret’s paternal grandmother, Ellen, was the daughter of James Campbell and Grace Hay. Ellen and David Dundas Whigham married in 1864 and a year later gave birth to their first child, Robert, who became a well-liked soldier. Nine other children were born in rapid succession – four girls and six boys, the last of whom, George Hay, Margaret’s father, was born on 24 September 1879. After the costly education of the first-born boys and supporting a family of twelve, the family’s money ran out and Margaret’s father began his career by serving a five-year apprenticeship in the civil engineering firm of Formans & McCall in Glasgow at a starting salary of thirty shillings a week. After the turn of the century, he found work in designing and costing at Renfrew Dock followed by the Highland Water Power Scheme and the High Level Bascule Bridge over Glasgow Harbour and later became involved in the design of material for the steel pier at Almeria in Spain. His worthy treatise Whigham on Light Railways, published in 1902, was read before the Institute of Civil Engineers in Glasgow and resulted in his being appointed resident engineer on the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway where, with a budget of £750,000, he became responsible for the design and execution of bridges, tunnels and stations. There would appear to have been no room for love in the life of a man so dedicated to his profession but he lost his heart to a pretty young Scots lass, who became Margaret’s mother.

A copper magnate and his wife lived in a large house called Broome at Newton Mearns in Renfrewshire. Their daughter Helen Marion was jealously guarded by her parents, who were highly suspicious of any suitor. By 1905 George Hay Whigham was twenty-six years old and had thoughts of marriage, but, although industrious and with good prospects, he was practically penniless and thus not acceptable to the wealthy Hannays as a suitable match for Helen, despite his charm and ardour. However, George had been offered an appointment in Egypt with the Wardan Estate Company and was about to leave Scotland to take up a five-year contract. He wanted desperately to do so with a new young wife by his side.

‘That was a very romantic story, my mother’s runaway marriage with him,’ Margaret said. ‘This very rich girl and this poor boy. She was rich because her father, my grandfather, was a copper millionaire by the name of Douglas Hannay. My own father was extremely difficult, obviously very bright from an amazing family of ten. He was going around all the parties outside Glasgow on the Clyde where all the people congregated, the industrial set who were going strong. The Williamses, the Sainsburys, the Inverclydes and the Weirs, they were all Scots from that part of the world. Very rich, very successful and they gave lots of parties. My father met and fell in love with my mother straight away at one of those parties. She was an awfully pretty woman; and also very petite, like a sort of doll. They adored one another. But he hadn’t any money. He lived on an allowance from my grandfather in Glasgow of thirty bob a week, about ten pounds at the time. Very little. He was a civil engineer, learning to be a chartered accountant at night school. Obviously very intelligent. Then he came to ask my grandfather whether he could marry my mother. She was a very spoilt girl. Had her own maid, got her coats from Paris. And my grandfather said, “All right, you’re going to Egypt. If you come back earning five hundred pounds a year you can marry my daughter” – thinking, he could never do that, and bye-bye, George Whigham, I’ll never hear from you again. And off he went to Egypt. Months later my grandfather saw a letter from my father on the table at breakfast. He knew what it was, that my father was coming back to ask for her because by now he was making five hundred a year and was returning on leave after six months in Egypt. But my grandfather said, “All right, she can marry him but she’s not going to get a penny from me.” He didn’t trust my father. He thought he was marrying her for her money. So my mother said, “Fine. I couldn’t care less. I love him and I’m going.”’

The runaway heiress and the young adventurer married and soon after ‘they went to live in the desert. She had two dresses a year and a hat, and she couldn’t care less. She adored him.’ Margaret inherited her mother’s headstrong, defiant nature but not her sense of economy. It was usual for Margaret to acquire five day dresses, five cocktail dresses and five ballgowns every season. She also inherited her father’s charm, adventurous spirit and his philosophy of never taking no for an answer.

Margaret inherited her mother’s beauty and vanity, too, and her ability to get what she wanted. She knew that her mother had found happiness by deserting her parents and running off with the penniless man she loved. This callous streak in her mother, the ability to cause family friction so early in her life, was another trait that showed itself in Margaret when she fell out in later life with her own daughter, Frances, and her grandchildren.

Whilst Margaret learnt her lack of respect for authority from her mother, she grasped the nature of greed and avarice from her father although he never succeeded in teaching her the value of money. She learnt only how to spend it – which is an art in itself. She also derived her social ambition from him. Margaret was his most prized possession and although all were allowed to admire, he did not want to part with it at any price. Father and daughter were deeply devoted to one another, but Margaret had no room in her life for her mother whom she felt stood between them. She could not understand that the love she demanded from her father rightly belonged to her mother. Just as she never shared her toys, she never shared her father.

The newly-weds spent the first four years of their married life in Egypt in which time George fulfilled his contract. By the time he was thirty he had managed to save over £10,000 through both his industry as a civil engineer and his accounting skills. During this period his brother Walter was employed by the finance company Robert Fleming and Co. in New York. In 1911 he encouraged George and Helen to join him in America and secured for George a job in the employ of Sir William van Horen in the construction of the Cuban Railroad. After his death the ambitious young George succeeded van Horen as president.

One of George’s other brothers, James, a former war correspondent with three worthy books on the Far East and golf to his credit, had joined the staff of the London Standard as foreign editor. He remained there for two years until 1908 when he became editor of both the Metropolitan magazine and Town and Country in New York. He provided George and Helen with accommodation in his smart apartment, and their home became the United States. Feeling settled for the first time since running away with George, Helen found herself pregnant. She became homesick, having spent almost five years away from her family and roots, and yearned to give birth near her mother, besides wanting the child to be born on Scottish soil. She also felt confident of forgiveness now that George had more than proved his essential worth. They returned to Scotland to the Hannay home, Broome, in Renfrewshire.

Her parents, however, were still angry with their wayward daughter, their disapproval justified when they realized that Helen had not come home for their sake but for her own. They were further incensed when they learnt that Helen would be returning to America once the child was born. They knew that they were being used. It ran in the blood.

On 1 December 1912 the Whighams’ only child, Ethel Margaret, burst on an unsuspecting world.

Chapter Two

Dance, Little Lady

When Margaret was a month old her parents returned to New York and there they stayed.

‘Of course I was too young to remember the Great War years but I do remember the celebration of Armistice they had in America. Everyone was yelling and cheering but I didn’t know what they were yelling about. I recall, too, an old HMV record playing, “Over There”, “The Yanks are Coming” and “It’s a Long, Long Winding Trail”.

‘My earliest memories of being a child were the sounds of the sirens of ships going up and down the river, no doubt because we lived in a duplex apartment near Central Park and the sounds were very loud and clear.’

Margaret acquired an American accent but little education. However, attempts to alter her speech to upper-class English with her mother’s eye to the future of her pride and joy were to prove abundantly fruitful in time.

Brearley, the school to which Margaret was first sent in New York, proved too advanced for her and on a visit to Britain in 1920 when she was eight her mother decided that an English nanny would be the most suitable way in which to rear her child. The family was staying at the Ritz Hotel in London, en route to visit the Hannays in Scotland, and it was here that Helen interviewed several prospective English nannies. The successful applicant was Nurse May Randall, who became the devoted servant until she married many years later. When they concluded their holiday in Scotland the three Whighams with Nanny May sailed back to New York.

As Margaret was brought up by her nanny she never became close to her mother. As an only child, surrounded by toys and cuddly teddy bears, she learnt to rely on the inanimate objects for comfort. Her mother and father were Victorian and strict Presbyterian Scots. Any strong display of emotion would have been alien to them and Margaret’s memories were always of material comforts rather than of parents who provided love and affirmation. Her mother showed her none of the caring for which she craved. Later in life Margaret would be guilty of the same cold, callous lack of emotion in her own dealings with people – both friends and family.

‘I was sent to a very famous school in New York after my first attempt at education there, which my father had helped to found. It was begun by an English woman by the name of Miss Hewitt who was a governess. She had managed to get four or five of the children’s fathers to finance it. George F. Baker was one and my father was another. But I nearly got expelled because I won three prizes in a row (through cheating). Greek history, Egyptian history and world history. In order to win them I had to write and find a picture for an album and in order to get a certain good one I got a library book, cut the picture out, put the book back on its shelf and stuck it in my album. When they discovered what I had done I was sent away under a very black cloud and I just shrugged the whole thing off and said, “Ça va.” Then when I went back in the autumn I found that everyone else had cut pictures out of the library books as well!’

Two of her closest friends at this establishment were Gloria, daughter of the famous Italian tenor, Enrico Caruso, and the Woolworths heiress Barbara Hutton, with whom in later life Margaret shared an insatiable enjoyment of men and money.

The reason for Barbara Hutton’s lifelong search for love and longevity might easily have been attributed to the fact that her mother had flung herself from a window committing suicide but Margaret’s reason for her own choice of lifestyle in later years was conceivably more complex.

She was unacquainted with the irregular verb ‘to love’.

When women love deeply they give of themselves wholeheartedly. They would sacrifice their lives and forsake their own children and friends for the man they cherish. By and large, Margaret’s love was unrequited. She never found such a man for whom she would give her soul. She loved her father deeply, but that was a different kind of love.

She came to realize that the love men feel was more akin to her own emotions. Theirs is, by and large, a physical, practical love, lacking in huge sacrifice. Men hold on to what they have created and built up for reasons of self-protection. To give is to gamble, and, therefore, possibly lose. Margaret shared this same sort of male caution.

Later she would love the man by whom she had two children, Charles Sweeny. But the love she felt for him was similar to his own practical, no-nonsense kind of love. When he went off the rails, so did she. It was quid pro quo.

She would never trust a man again after he had betrayed her love. Like his, her love was physical.

Her need for security stemmed from the fact that she had always had it and feared losing it. She had never worked for a living for one day in her life.

In consequence, she never really understood or appreciated the true value of anything in life. Neither spiritually, emotionally nor financially.

During this time Margaret’s father was heavily involved in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway while gaining ground in the area which made him his fortune, the development of Celanese fibre, with the support of his brother Walter. The young family continued to spend their annual holidays travelling to Europe where George Whigham had met the inventors of the new fabric in Zurich.

In sharp contrast to her father’s activities, Margaret’s mother was concerned about her fourteen-year-old daughter’s future. ‘The reason my mother came back here to Britain was because at that time all the kids who had become kind of débutantes in New York had been getting terribly drunk, and they were lying around on the sofas out like lights on the very bad stuff they were giving them. Although my mother had visions of me getting drunk, actually I never drank anything. So they brought me to England where they took a house at Ascot.’

The manor house that the Whighams took in this highly fashionable area of Berkshire was called Queen’s Hill; it was set in thirty acres of land facing the world-famous racecourse and they gave house-parties during the racing season. When they were in London they lived in a rented house in South Audley Street in Mayfair.

‘We had been coming backwards and forwards after the war every summer by then and I had crossed the Atlantic fourteen times by the time I was eleven years old. To me it was like taking a train to Glasgow. Although it became terribly boring it was very exciting to other children to get on the Carmania, the Olympic or the Mauretania – but to me it was absolute peanuts.

‘One of my greatest difficulties in leaving America was because of my teddy bears. I couldn’t have any live animals in New York so I had my teddy bears which I loved. Brownie, Blackie and Teddy. They were so much loved and kissed that I had kissed them bare. I used to make little coats for them. They had their own wardrobe trunk, hangers, chest of drawers, bed, pram, cot. Their own luggage. And once my father said, “I’m damned if I’ll travel with those blessed bears’ luggage any more.” And I said, “In that case, I don’t go.” We had a confrontation over me and my teddies at a very early age and I won.’

When they returned to England permanently, Margaret’s education was of prime importance but remained patchy. She was sent first to one of London’s most fashionable private schools in South Audley Street under the tutelage of Miss Woolf, who taught the Duke of Norfolk’s sisters, Lord Curzon’s daughter (who became Baroness Ravensdale) and Jeanne Stourton who later married Lord Camoys’s only son, the Hon. Sherman Stonor. Two others were Cecil Beaton’s sisters, Baba and Nancy. She went for dancing lessons to Madame Vacani whose privilege it was to teach the waltz and quick-step to Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret Rose, and later to Prince Charles, Princess Anne, lesser royalty and the aristocracy.

Margaret was then dispatched to the exclusive girls’ school Heathfield as a day-girl, ‘And I hated it. It must have shown because I wasn’t very popular. I couldn’t abide boarding schools for girls. I was a spoilt only child, more sophisticated than the others, and when I was collected in a chauffeur-driven car to be taken back home to Queen’s Hill in Ascot every day, I’d say, “Bye-bye, you poor things, playing in your galoshes and white tunics.” I had no esprit de corps, and certainly didn’t want to play hockey or lacrosse or cricket with anybody.’ Her sporting activities were confined to the indoor variety for many years to come.

‘I don’t like women in a mass. I think they should be individuals. And these girls were being told constantly when to wash their hair. And I kept telling them to stop being told when to do so. I was then asked to either conform or to leave. So I left. I went after only a year. My parents were always trying to get me out of England to Europe, to Austria or Switzerland to have a healthy, outdoor life because I was growing up too fast.

‘Then I was sent to a fashionable finishing school in Paris run exclusively for English girls which I equally loathed. It was called Ausanne. Run by Madame Ausanne. I was there for three ghastly months. And that was the end of that!

‘Education was never my strong point. I absorbed a great deal from being with grown-ups, though. That’s how I learnt. I heard them talking and I used to listen quite hard. I never liked people of my own age, ever. I preferred older people and I simply adored being an only child. Adored it. The greatest threat you could give me was when my mother used to say, “If you’re naughty, you’ll have a little brother or sister.” And I used to say, “Anything, anything but that!” I was completely self-sufficient.

‘In her way my mother was very selfish. She was a strange mixture. She was extremely unselfish to my father and married him on nothing. She adored him. He was the love of her life and she helped him build up his vast empire. She could get people to communicate with her. If you were talking to her you’d be telling her your all.

‘I don’t think I look particularly like her. I don’t look like either parent. Perhaps my grandmother. My mother’s mother was a very beautiful woman. She had the green eyes which I have. My parents both had blue eyes. My mother was tiny. She was very petite. About five feet two. And everything to match. She had tiny hands, tiny feet. Like a doll. And she was terribly funny about herself. She had a tremendous sense of humour but in her way she was very selfish. But she was also loyal and she was extremely spoilt in her way. She had tremendous charm. She could charm a bird off a tree and she was absolutely un-shy. That’s where I get it from. I have never been shy.

‘She was a very open person. Very uncomplicated and easily impressed by anyone or anything. And she was very fey. They call the Scots fey. She’d had absolutely no education. Talk about me having none, she had less. But she was very spoiled and accustomed to being the centre of attention. She was one of three children. She had a brother, and a sister who was very pretty and chic. Beautifully dressed and groomed, she was a very active person who played golf and tennis. My mother was supposed to be the ugly duckling but she wasn’t ugly at all. She could also be very moody. If she’d had a bad night, you couldn’t make a noise the next morning. She was extremely good at running the house and the servants adored her. But she was tough with them, much tougher than I’ve ever been. She was very spoiled and accustomed to being the centre of attention but although she was almost illiterate she had the most extraordinary instinct. You couldn’t lie to her or fool her. She had an X-ray mind, which my father hadn’t. My father who was a very charming and brilliant man was very tough in business but he was awfully gullible. Which I am. Very gullible. They fool you every time. He’d ask my mother about something, about a partner or a director of the firm and say to her, “He’s very nice. He’s very respectable. He’s got credentials.” And my mother would say, “Don’t touch him. I don’t like him. He’s a crook.” She had extraordinary perceptiveness which I haven’t got. As I said, I do have my father’s gull—gull—[another hesitation, then] gullibility.’

Margaret inherited her occasional stammer from neither parent and hard though she tried to conquer it throughout her life she never succeeded. Yet, strangely enough, as she grew older this inability to speak fluidly lent its own attraction. Men felt she lacked confidence and offered her a supportive arm on which to lean. It became one of her compelling yet unwitting charms, a dangerous spell for those who fell for her façade of vulnerability.

Her mother had explained that unless she managed to overcome her impediment she would achieve little in life, and although this advice was meant constructively the psychological effect of it worsened the problem. Despite visits to specialists in New York and London, and a final effort by speech therapist Lionel Logue who treated King George VI, she retained this imperfection in an otherwise glittering life. No one realized that the cause stemmed from Margaret’s having been born left-handed and always forced to use the right which led to marked physical and psychological feelings of inadequacy. Her mother’s final advice, when it was discovered that Logue could do nothing for Margaret, was to persevere. Helen warned that a hard road lay ahead of a girl so worldly, charming, beautiful and, probably, richer than other girls of similar background unless she redress this imbalance. Margaret could become a recluse unless she learnt to fight her handicap: if she ran away from life because of this blight she would meet fewer and fewer people, be unable to answer the telephone and find herself incapable of conducting herself confidently, ending up lonely and desperate for company.

Yet the stammer was not only caused by feelings of inadequacy: there is no doubt that being the only child of a cold distant mother and a doting but absent father played their part in undermining Margaret’s sense of security. That she did eventually become lonely, desperate and outcast from society at the height of her beauty and social acclaim was for reasons unconnected with the speech impediment.

‘My mother did the awful thing of telling me about sex. I wish to God she had shut up. You don’t know about it but you don’t want to hear about it. And her attitude was, “It’s this awful thing we women have to put up with. We close our eyes and bear it.” And I just didn’t want to know. I was extremely independent as a child, perfectly happy to be left alone, which was rather rare, but I was always very busy.

‘My father and I were very much alike. We were both arguers. He taught me how to argue, which you do without anger, or anybody banging doors or raising voices. He taught me to argue pros and cons and my mother couldn’t understand this at all… People loved him. He was a very good employer. He would have been a very good Labour leader although he wasn’t particularly politically minded. He was all for Roosevelt in the days when everybody thought that Roosevelt was very far left. My father was always for the worker.

‘My parents had a very good time together, really. They were obviously fond of one another. He was a very good-looking man but he was very unfaithful to her and made her unhappy at times. She went off and left him once with me. We were in Biarritz for the winter, as I remember it, and she’d had enough. But my father pleaded and got her back.’

George had spent the previous six years in America developing the revolutionary new man-made fibre Celanese. The industry expanded rapidly into Canada and Britain and, through his hard work, he became chairman of the company in all three countries. This was not achieved through tenacity alone but also through his extraction of the patent from the control of the Swiss inventors.

‘There were three scientists who came from Zurich. They were called Dreyfus. There was Dr Oriol Dreyfus, Dr Camille Dreyfus and then there was Dr Henry Dreyfus. They invented a thing which was called viscose-acetate which was a man-made substance that came out of a tube. And that was artificial silk. It was the first time that it was ever invented. It was before Dupont. This was the first and they called it Celanese. My father discovered the Dreyfuses. He was a very far-seeing man and he foresaw the future of this which was rather extraordinary. It was in 1921 or so. He told them he would put it on the market because they didn’t have a clue how to go about doing so. So he said, ‘Just keep on inventing’, and he would see to the rest. And so that’s how Celanese was born. The rivals, Courtaulds, called theirs Melanese and they were the two big beginners of artificial silk. Up to then people were in lisle and raw silk stockings. Nobody ever knew about anything else. So my father put every egg he had in that basket which was quite a gamble.