Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantis Verlag

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

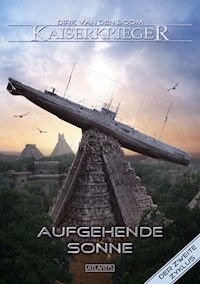

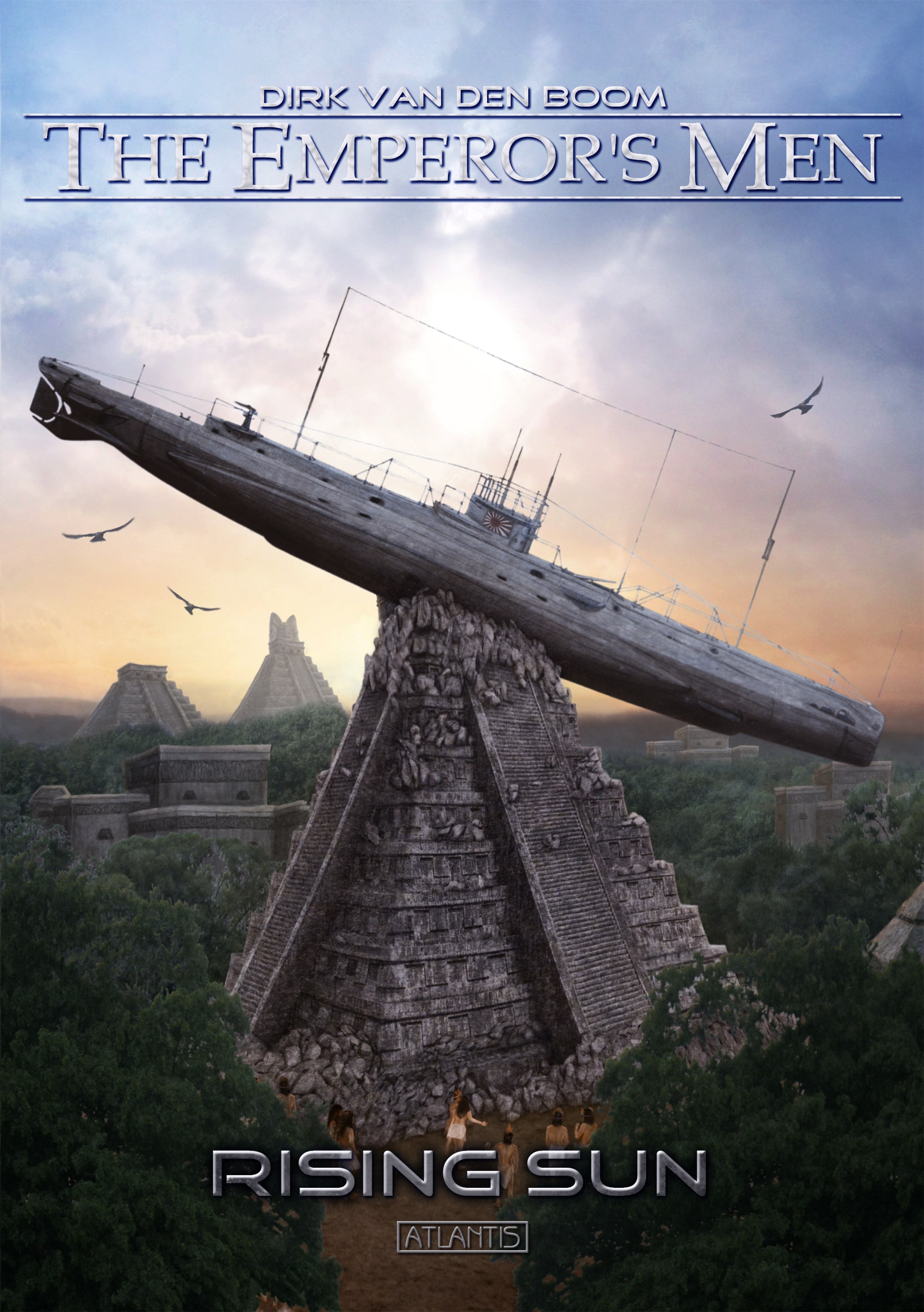

The new submarine flotilla is the pride of the Japanese Navy. The maiden voyage of the newest boat not only attracts the attention of the Imperial family yet is at the same time a test for the selected crew. But shortly after departure, something mysterious happens: The submarine seems to sink and all crew members lose consciousness. When they awaken, they realize with horror that their boat has left its element. It rests on the top of a gigantic tomb for the King of Mutal, lord of the largest metropolis of the Maya, in the middle of the Central American mainland, some 1500 years in the past. The confused crew goes straight into war and faces the crucial question of where their path will lead them now – to an empire or straight into disaster?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 468

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Inhalt

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

Epilogue

List of characters

Dirk van den Boom

Rising Sun

1

Yumiko Hara tugged at her son’s lapel, though everyone in the room knew that no power in the world could perfect the fit of the uniform’s jacket. However, this didn’t prevent the older woman from trying again and again, and her son Aritomo allowed her to do so. He knew that this activity helped her to hold back the tears that would shortly be released once he stepped out of the small house to begin his trip to Yokosuka. His mother would cry, his two sisters would cry, and the only one who would remain silent was his father, at least as long as everyone watched.

Aritomo looked out of the corner of his eye to the left and right. In the small living room, on the sofa, directly under the great portrait of the Tenno, his sisters Akemi and Beniko crouched. Akemi’s wedding had been the occasion for his return home. Normally, a young officer of his age hardly got any leave, but his older sister’s wedding had been occasion enough to soften the heart of a supervisor, giving him the necessary permission. Certainly, the upcoming mission was also important. As with all maiden voyages, a lot could go wrong, and this was even more true for …

His gaze wandered, clinging to the portrait of his grandparents, two fading photographs that barely discerned anything, and then there was the small altar designed to honor his ancestors. The living room was the largest room in the small house, but when the entire family gathered, it was quite full.

Existence has always been like that. The father’s rigid gaze, full of expectations and observing if everyone followed consistent rules, had determined his life. Full of discipline. The care of the mother, overwhelming when the father was not looking, the only way for her to express anything other than obedience to her husband. Full of love. The sister, intimidated, with her eyes steadily turned to the ground, flinching when the father raised her voice. Or the hand. Full of violence. The old furniture with its smell of wood, the odor of shavings and remnants from the workshop, strangely mixed with the scents of the kitchen, all put together, side by side, with only the father’s chair as the only comfortable seat on which no one except him was allowed to settle. Full of hierarchies.

The pictures of the Emperor. On each wall one. Almost of it real size, framed.

Full of respect.

Maybe it was silly that Aritomo Hara had been able to free himself from this confinement by joining the fleet, a hierarchy as crushing as his father’s rule over his family but promising the prospect of liberation, he hoped. Climbing up the ranks, gaining his own command, and finally able to be his own man, to stretch his neck out of the narrowness and out of submission by shouldering his own responsibility.

And now his first, the most important mission, was about to begin, and parting from the family was not bitter; he looked at it like a release from jail, warm as he was to his sisters.

Aritomo urged himself to wipe away the thought. He hadn’t been allowed to tell anyone what the mission was, and he had stuck to it. His father didn’t ask questions and had forbidden his family to touch the subject. He was certainly proud of his son, more than he ever expressed. He was obedient and hardworking, disciplined and honorable in what he did – and everything he had ever expected of him had always been woven into exactly the same tight corset carried by the narrow shoulders of the adolescent boy since childhood. It had been the promotion of Aritomo to Kaigun Chui, Second Lieutenant, which had finally allowed Akemi to bring the marriage to the son of a middle-ranking official to a successful conclusion – her liberation. She was so happy that she had begun to cry hysterically at the news. Normally, a simple artisan’s daughter would have been barred from even considering this social advancement. However, when the prospective father-in-law had heard of Aritomo’s admission to the Officers’ Academy, it had already been suggested that the first promotion from Cadet to Lieutenant would make the Hara family worthy enough. Akemi had been very happy. Aritomo knew the husband. He was not half as rigid, immovable and domineering as her father. He would give her the freedom a girl from a humble Background could expect, and that was all Akemi needed to feel complete bliss. Beniko would surely find a husband as well, whose status was above that of a craftsman. The biggest hope for their mother Yumiko Hara, however, was, that her son, perhaps after another promotion, would himself be connected to a daughter of one of the higher officers’ houses, possibly even of nobility. Successful officers were of status, everyone knew that. That was the point where his mother’s hopes met his father’s, a point where even he himself sometimes agreed to have a serious interest in.

Aritomo was silent on these plans. He intended to focus on the fulfillment of his duties that finally would enable such promotion. A focus which required his deepest concentration, much the same as his mother gave to the uniform jacket.

“You must look good, son.”

“Yes, mother.”

“Did you pack everything?”

“Yes, mother.”

Yumiko Hara had checked his duffel several times. She had washed and starched all his clothes so neatly that, if one looked at them closely, they seemed to shimmer out of themselves in a strange way. Probably you could place each shirt upright on the shelf. Or hammer nails with it.

“I’ve packed you travel provisions, son!”

“Thank you, Mother.”

The small shoulder bag had been handcrafted by Yumiko, with an artfully embroidered flag, the rising red sun, the flag of the Imperial Japanese Navy where her son served. And that should really attract everyone’s attention on the long train ride to Yokosuka. The contents of the bag consisted of delicacies wrapped in oil paper, into which Yumiko Hara had put all her creative power as a cook. Her son would certainly not starve on the journey. Maybe the otherwise so perfectly fitting uniform jacket would get tight in the abdominal area. But starvation was out of the question.

“Mother, I have to leave. The train is leaving soon.”

“Yes, yes, I know.”

Yumiko’s answer sounded a bit lost, and when she tugged at his lapel again one last time, Aritomo saw the soft moisture of tears in her eyes. Regardless of the fit of his jacket, he took the slender figure of his mother in his arms. He had spent a week with his family. He knew that years could pass before he met all of them again. The service of an officer was exhausting, and there was little free time. Writing letters was all that was left to him, and even that option wouldn’t be available to him always because of the nature of his duties.

Yumiko Hara broke away from the embrace and looked reproachfully at her son, eyes covered with a tearful veil. “I’ll wet your jacket! That is not right! You have to watch your appearance, you’re an officer!”

Aritomo surrendered to his fate, allowed her to dab the barely visible damp stains off the fabric. His mother did so with the quick, precise hand movements with which she did with everything she had to do, movements all too familiar to her son.

“Leave it, it’s time,” her husband’s growling voice said. No hug, just a grab on the forearm, a quick pressure that said everything his father wanted him to say, and there needed no further words.

Afterwards, everything went very fast, mercifully fast. They stopped at the shrine to ask the ancestors for a blessing for Aritomo and then the Tenno. Their prayers were accompanied by one of the monks, whom they motivated with a small donation to a special prayer. The ceremony was short but serious, and his family’s faces had been full of pride and respect. For them, what the son had accomplished, was of extraordinary importance.

They had arrived at the train station, where, despite all their self-control and formality, at least the mother had cried silently once more, carefully hidden from the public by her relatives’ bodies. Aritomo had booked second class and enjoyed the relative luxury of a neat seat. His compartment was empty when the train rolled in, but that wouldn’t last for long. He waved and looked out of the window until the station had disappeared in the distance and not even the fiercely whirling white handkerchief of his mother was still visible. Only then did he sit down, filled with wistful thinking about his goodbye on one side, full of anticipation for the coming challenges on the other.

For half an hour, he enjoyed the silence, staring out of the window, as the suburbs of Kobe slowly moved past him, and the express train picked up some speed. At the next stop, more passengers climbed in, some joining his compartment, including an old man with a white beard, stock-still in his slightly scuffed suit, bowing slightly to Aritomo. This was rather embarrassing for the young man, but he told himself that the respect was for his uniform, not his plump baby-face, which he had somehow preserved despite his 26 years, and which may have contributed to the fact that he triggered more maternal reactions in women than romantic ones. There were also two other soldiers, apparently returning home from leave, both infantrymen, both older men, senior NCOs, as Aritomo recognized. They greeted each other with formal courtesy.

To avoid a conversation among comrades he didn’t desire at the moment, Aritomo pulled out the newspaper he had bought at the station. He glanced at the date. It was late August in the year Taisho 3 or Koki 2574, a year that, according to the powers engaged in a great war against each other in distant Europe, was also counted as 1914. The events of the war that broke out less than two months ago dominated the headlines. Aritomo had been given instructions from his superiors before he had been granted leave to only convey Japan’s official stance in conversations that their own legitimate interests – especially in Russia and China – would be duly considered, and at most some support would be given to the British allies, such as escorts. In general, however, it was believed that Japan’s involvement in this war would be marginal. Aritomo had kept his relief for this attitude to himself – other officers, superiors, had been disappointed – and found nothing in the paper that changed that impression. According to the reports, he felt that this dispute would take longer than expected, and if the imperial government played its cards properly under the Emperor’s wise leadership, Japan could emerge stronger from this mess than before.

Aritomo pondered for some time on the military and strategic implications while leafing through the rest of the paper, finding nothing of interest, then folded it neatly on his thighs. The rocking of the train had something reassuring. He hadn’t slept much last night, for he wanted to enjoy the last evening with the family, and had talked to parents and sisters until late at night, and had waken up early in the morning so he wouldn’t miss the train.

Aritomo closed his eyes and decided to go to sleep.

Fortunately, the journey was uneventful. Among the missing events he was able to avoid unpleasant and exhausting conversations with fellow travelers, the feeling of hunger and a sore back. Aritomo was very fortunate, as far as his fellow travelers was concerned, could easily satisfy himself with his mother’s supplies and, moreover, knew why he had spent the money on a second-class ticket. As the train finally arrived at Yokosuka Station in the evening, the young man was maybe tired and a bit tense, but all in all in good shape.

From the station, a bus drove regularly to the Naval Arsenal, the base where Aritomo had to report on time the next morning. Yokosuka was a big city with a glorious history dating back to 1063. Here was the first modern shipyard in Japan. Here was one of the central naval bases of Nippon Kaigun, the navy of the Empire of Greater Japan, whose proud member Aritomo had been since the age of 17.

Just this one mission, his superiors had told him, and the promotion to Kaigun Daii, full lieutenant, was imminent. Aritomo’s ambition was not excessive. He didn’t dream of the admiral’s staff, only of his own command. And he would already achieve this with the rank of a lieutenant, because the division of the fleet in which he was employed offered ideal conditions for a career. Lieutenants had already been appointed commanding officers, and Aritomo himself would now serve as first officer. There were not many who could claim that at such a young age.

It was quite possible in Japan’s small but ever growing submarine fleet.

His papers were thoroughly examined when he got off the bus, and that although the officer on watch was a familiar comrade of his; he exchanged a few kind words with him. It was already dark, when Aritomo had finally reached his quarters, a small room only sparsely lit by a gas lamp, spartanly furnished.

Despite the long trip, he felt a certain restlessness that wouldn’t let him sleep. He stowed his luggage as far as it was necessary in view of his imminent departure. As a second lieutenant, he enjoyed the privilege of sharing a room with just one comrade, and at the moment the second bed was empty. A room for himself, that was something that irritated him. He had none at home, he had not enjoyed any during training, and he would serve on a submarine that barely gave him his own berth. Aritomo wasn’t used to privacy. It made him restless.

He therefore decided to give his mind some rest by taking a walk in the calmness of the evening. As he stepped outside, he unconsciously steered his steps toward the harbor, where Navy ships were moored. He marched past the mighty units, ignoring them until he came to that guarded area where the small submarine fleet of the Empire was to be found. His face was known, yet his papers were re-examined thoroughly. Then he was let into the locked district, which was so well guarded because Aritomo’s boat was stationed here.

He wandered the black shadows of the small Holland boats that still formed the backbone of the tiny fleet and where he had served at the beginning of his career. He liked to think back to that time, despite the very cramped conditions aboard the units, and the fact that these American designs were constantly struggling with all sorts of technical issues that severely affected their operational readiness and range. Aritomo had in the end served as helmsman on one of those cramped, thick-bellied boats, one of only eight crew members, and it had been a torture. But the need to build a submarine force hadn’t been ignored by the Admiralty, and so they turned to the British – who built the Holland licensee – and looked around for improvements.

Aritomo’s eyes fell on the very peripheral construction hall, half on land, half in the water. It was particularly secure, with additional guards, and he wouldn’t gain access at this time, though he would be the first officer in the vehicle to wait for its maiden voyage tomorrow morning.

A big secret, but not one that would be kept as such for a long time. Aritomo felt a deep satisfaction that he was allowed to participate in this historic moment. If everything went well, he would make his nation and his parents proud, and if he increased his experience as a submarine officer by doing so, his own command was just a formality. His goal to train new officers at the Naval Academy would sooner or later be realized. He liked to teach and he liked to learn. A career as an instructor, in addition to his own command, was the central goal of his ambitions.

It looked good.

Everything in his life had developed wonderfully.

“Can’t sleep?”

Aritomo turned to see Yuto Sarukazaki in the twilight. The Ittoheiso was the oldest member of his crew, the highest non-commissioned officer and at the same time the chief engineer of their boat. At almost forty, he was a formidable figure. Aritomo liked the pragmatic and effective man, and he liked to listen to his advice. This put him in sharp contrast to the captain and joint superior, Lieutenant Inugami, who insisted that the sharp line between officers and the rest couldn’t be transgressed by informal behavior and exaggerated camaraderie. Why did he insist on such things in the oppressive narrowness of a submarine? Here, where a cordial cooperation between all soldiers was necessary, one didn’t want to get on someone’s nerves quickly. Aritomo didn’t understand. For him, submarine people were a special kind, for which some of the very rigid rules prevailing in the Navy didn’t apply. Locked in a metal can, threatened by a particularly cruel death, this shared destiny – the real and the potential – should make a different kind of personal connection possible.

Inugami had probably never really gotten used to this idea. But the difficult superior would remain an episode, something to endure on a path that would take Aritomo past it.

“I’m not tired yet,” Aritomo replied, tilting his head toward the factory floor. “I can’t wait.”

“I understand you well. But it doesn’t seem like everything will go as planned tomorrow.”

Aritomo looked up. “What happened?”

Sarukazaki had a cigarette in his hand, its red glow well visible in the darkness.

“While you were on vacation, plans have changed. I don’t know any details; so far only Inugami has been informed. But he looked so happy and pleased that an important announcement must be imminent.”

Sarukazaki apparently wanted to add something, but then thought better of it and said nothing. Anyway, Aritomo guessed what he had meant to say – anything that pleased his stern commander didn’t necessarily have to be positive for the rest of the crew. Inugami was far more ambitious than his first officer and ready to give anything to position himself in the right light. Aritomo knew that some of the crew members called him “Lieutenant Taisho” behind his back, hinting to the man’s clear aim to rise to Admiralty rank as quickly and effectively as possible.

Aritomo always pretended he didn’t hear those remarks. He didn’t like the man, but to obey was his duty. After all, Inugami was only a year older, and therefore it wasn’t so natural for him to beat Aritomo if he didn’t quite do what the commander had asked him to. With the other crew members, perhaps with the exception of the much older boatswain, he dealt liberally with corporal punishment. Blows in the face were not uncommon. Aritomo didn’t belong to the faction among Navy officers who considered this tradition to be meaningful. He didn’t employ beatings, as was his freedom of choice as an officer.

But who was he to fundamentally question the traditions? That was indeed the job of an admiral.

“No rumors? Normally, lower ranks know more about everything than we do,” Aritomo insisted.

Sarukazaki grinned, showing his immaculate white teeth, which Aritomo secretly envied. He took a last drag from his cigarette before dropping the shimmering rest to the floor and putting it out with the heel of his shoe. As a smoker, it was difficult for him to forgo his addiction for weeks while confined in a submarine, aside from those spells they stayed above water.

“Security measures have been stepped up, there are extra guards, and our commander is dripping with joy – I suspect we expect a really high visit to celebrate our maiden voyage. Probably someone from the highest ranks of Admiralty, if you ask me.”

Aritomo nodded. This supposition did indeed fit well with his own speculations. “Then we should be ready,” he said, taking in the cool evening air before turning around. “I’ll try to find sleep now. I suggest you do as well, Ittoheiso Sarukazaki.”

The man stood tight and saluted with a smile. “Yes, Sir.” With that he turned away and disappeared in the darkness.

Aritomo paused a moment longer before following his own advice. If it was true what the man had told him – and that something was in the works there was no doubt –, he would need all his energy tomorrow in order to make the necessary preparations.

And to endure the slimy anticipation of his commander.

If he liked it or not, now was time to endure some privacy.

2

“Men, we have a great time ahead of us!”

Kaigun Daii Tako Inugami teetered on tiptoe, and almost smiled at the crew in front of him. This was unlikely – Inugami never smiled –, but he radiated such a sunny enthusiasm that no one really wanted to believe.

The thirty crew members under the command of the lieutenant had gathered in one of the classrooms. The fact that they were allowed to sit down right away spoke for the exceptional good humor of their superior. Normally, he gave a speech without worrying about the well-being of his men. Inugami himself liked to stand and endure, a passion that was not shared by everyone.

“I received the news a few days ago that the maiden voyage of our new boat will receive the utmost attention. I’m not talking about the Admiralty here – although of course they are very interested in the results –, but I mean the very highest attention.” Inugami leaned forward and lowered his voice to a devotional volume. “His Imperial Highness, Prince Isamu, will accompany us on our journey.”

Silence descended across the room. Inugami apparently enjoyed the awesome horror sparked by his news. Aritomo felt contradictory feelings. Of course, to be visited by the second son of the Tenno, to be able to enjoy his presence more than with a fleeting glimpse, that was more than an honor, it was an event of which they would all tell their grandchildren and grandgrandchildren. Aritomo was filled with deep reverence for the imperial family, and he was delighted to attend the military parade for the inauguration of the current Tenno two years ago. Isamu was born shortly after Hirohito, the crown prince and heir to the throne, and his mother was an imperial concubine, just as Tenno Taisho himself was the son of a concubine. There was nothing honorific about that, and their wives had quickly recognized these sons as legitimate members of the family. Isamu was thirteen years old and enthusiastic about anything to do with ships. As he knew, unlike his brother, he didn’t visit the Gakushuin School, where the nobility’s offspring was commonly educated, but had been enrolled at one of the preparatory cadet schools, to be able to embark on the career of an officer. One never saw the young man in public in any other attire than in the uniform of a cadet, and no one doubted that he would once become an important military leader.

Besides, he was considered reserved and reclusive, almost shy, always in the shadow of his older brother, only a few months his senior, who would most likely follow on the throne. Some said he was jealous, but that was just rumors. But the descriptions of the young man as very calm and withdrawn, rather slow and deliberate, persisted so much that Aritomo was ready to give them at least some attention.

He cleared his throat.

“But Lieutenant, is that wise? Such an illustrious person on the maiden voyage of a new submarine? Is he not putting himself in unnecessary danger?”

Inugami gave Aritomo a dismissive look before settling for an answer.

“Maiden voyage or not, we’ve checked the boat extensively already. It works flawlessly, as the tests have proven. The young prince has made an explicit request, and it should be our highest aspiration to fulfill it. A few hours aboard our new and big boat can’t be a big risk.”

Aritomo bowed his head. “I understand. Will the Imperial Highness come to us alone or with company?”

“No, of course not alone,” Inugami replied in a tone that clearly expressed how stupid he considered at the question. “His personal tutor will accompany him, as well as two bodyguards. We will not travel far. It won’t be a problem to accommodate four additional men for the duration of the journey.”

“Of course not,” Aritomo confirmed, saluting.

“I want the boat to be cleaned thoroughly today, so thoroughly that there’s nothing left to clean.” Inugami turned to everyone. “I expect the very best effort! I will make a very, very strict inspection tomorrow morning, before the highest guest visits us! Everything must be absolutely flawless! If I recognize sloppiness, this will be severely punished! And I expect absolutely perfect behavior and one-hundred per cent discipline on board! No one fails in anything, everyone works with focus and diligence! Second Lieutenant Hara, you oversee all of this. Report to me regularly. Punish them if there are omissions. I set the highest standards!”

Certainly, there was no doubt about that, Aritomo thought to himself but otherwise only stood stock-still, making the servile impression his superior expected of him.

The briefing was somewhat lengthy, as in addition to the expiration of the maiden voyage – it should take a total of about two hours, including about an hour under water – Inugami’s repeated admonishments to be aware of the particular situation and appropriate behavior took a lot of time. Even a deaf soldier with low intellectual abilities would have understood it by now and the crew of the boat really wasn’t made up of fools. When the grueling session was over and Inugami left Aritomo, the very attentive observer could see relief in the faces of the men. The captain had no eye for it, because he said goodbye with an urgent appointment in mind. Aritomo had no doubt that he had much to discuss with the leadership of the base to prepare the arrival of the highest visit in full, leaving nothing to chance. On the other hand, it left him with the exhausting work that was now required – the re-examination of all equipment aboard the submarine and the detailed and very, very thorough cleaning. This was an activity no one liked, and so the mood among the men was not half as euphoric as Inugami surely expected them all to be.

But actually, that didn’t matter.

Whatever the circumstances, Aritomo loved to be on the boat.

When he saw it lying in the water in front of the wharf, dragged out of the workshop for presentation, his heart pounced. The mighty body of the gray-black boat was impressive. It was a British design, the so-called E-Class. The British government had just recently given Japan the license to build this vehicle – more or less unofficially. With a length of around 54 meters, it carried eight torpedo-tubes. Under water, it reached a maximum speed of nearly ten knots with its electric motors – something they would, officially, try on maiden voyage. It could, the British said, dive up to 30 meters deep, and that was something they hadn’t done in the testing rides yet. Aritomo was sure that it could go a few meters deeper. He was eager to test the limits of the boat, though he certainly wouldn’t be allowed to do so with the Prince on board.

With a total of 31 crew members, the boat was so extensively manned that, unlike the older and much smaller units, it had earned itself the presence of two officers. There were four NCOs, mostly with specializations like the experienced Sarukazaki. Thus, 25 ordinary crewmen remained. On board this boat, there would be no fresh recruits, only sailors who already were experienced. For experiments with inexperienced crewmen, this first of its kind was much too valuable. They were veterans, as far as the young submarine fleet of the Empire had any. Aritomo had had plenty of opportunity to familiarize himself with the men. They were all disciplined experts, men with great personal courage and the level of sacrifice necessary to face the dangers of traveling beneath the surface of the water in a tight metal shell. Howsoever the maiden voyage would go, the crew would do anything to make it successful, whether with a Prince as a guest or not.

Moored with bolts in front of the tower stood the second weapon of the boat next to the torpedoes, a twelve-pounder. For this cannon, they had four trained gunners on board, and everyone had at least one extensive training session with it. That was just one of the key innovations in comparison with the old boats, which had relied exclusively on their torpedoes. It was these and other design changes that were to remain hidden from Japan’s enemies for the time being, and that had led to not station this new boat in the Kure fleet base, but rather here in Yokosuka. Once the boat’s existence was officially admitted, it would be transferred to Kure to lay the foundations for the second submarine flotilla, which would make the old Holland boats, including their successors improved by Kawasaki, obsolete.

But before that, there were more mundane tasks, especially now, and the most important thing was to scrub and polish the No. 8 boat, so that it shone like silverware despite its dark gray color. The Prince shouldn’t have any reason to complain, in this Aritomo was quite in agreement with his commander.

When the men started the work, Second Lieutenant Hara was not shy, while he supervised the joint effort, to pick up a rag himself.

It wouldn’t be lack of effort from his side, he thought, if anything was found to be amiss during inspection.

Certainly not from his side.

3

There was no music and no large parade.

Prince or not, not too many people were supposed to know what a great new submarine the Japanese navy now possessed. So they kept the occasion somewhat under wraps, as far as that was possible with the attendance of a member of the imperial court. A column of four cars had pulled up, and next to the crew of the boat, a company of honor stood rigidly, fully dressed and thus in stark contrast to the submarine’s men, as they wore uniforms, although clean, appropriate to the mission at hand.

Inugami had inspected the boat in the late evening, and for once had been satisfied. Despite intense scrutiny, he had noticed nothing negative, which he had acknowledged with rare praise. Everyone had noted this with relief, because Aritomo could testify that they had really made an effort.

Inugami had told them that the group of passengers would be extended by one more person. An engineer from Kawasaki would participate in the maiden voyage, officially to be available for explanations, unofficially, in order to gain additional expertise in case of problems.

That was logical and understandable, even a welcome development, as the First Officer secretly thought, despite the increasingly cramped conditions on board.

Problems could always occur. Aritomo remembered, like all his comrades, the fate of Boat No. 6, which wasn’t able to surface when it stranded in depth of only ten meters due to a technical failure in a dock. The old Holland boats had provided no device by which the crew could have left their prison in submerged condition. So the men had stayed in their posts until they suffocated, only a few yards from the shore. Only the next day had it been possible to lift the boat and recover the corpses of those heroes.

The boat was now a memorial. It reminded of the dangers of this new technology.

Aritomo’s gaze wandered over the hull of boat No. 8. The new design made it possible, as far as the depth allowed, for the men to leave the boat when it was beyond salvation and the surface wasn’t too far away. So hopefully they would never share the fate of the deceased.

Nevertheless, the man from Kawasaki came along. He had been, it was said, involved in the construction of this boat from start to finish, and knew it even better than the good Sarukazaki, who had dealt with every nook very intensely. Aritomo didn’t want to admit it, but the fact that the engineer was on board was already reassuring. And the new boat was so much bigger than the old Holland units. They would certainly be able to manage for the short trip that was planned. Orders were shouted. The honorary company presented the rifles. The submariners stood upright on the spotless hull of their boat, only Aritomo and Inugami had positioned themselves in front of the gangway over which the Prince would step.

When he left the car, suddenly there was an awe that seized all men like a paralysis. A scion of the divine Tenno was and remained something very special, and nobody could escape the charisma of the Japanese imperial house. The young man – the boy actually – looked perfect in his cadet uniform, which fitted like a glove. His illustrious father’s face was recognizable on his own features, if one dared to look at it long enough. His cheeks were a bit roundish, but his gaze was as majestic and penetrating as one would expect. His companions came as announced: an elderly gentleman who had to be the tutor, two wiry soldiers clad in a plain black uniform who were undoubtedly the bodyguards – armed with a pistol and a sword, a rifle on their back, as Aritomo registered, and then a man in civilian clothes, not much older than Inugami, carrying a large black briefcase. The engineer from Kawasaki.

Aritomo’s eyes widened.

A gaijin.

The officer controlled himself. Naturally. He could have anticipated that. The boat was built based on plans of British manufacturers. There was a long tradition of cooperation between Britain and Japan, especially in the development of naval forces. And British engineers often ran around in the big yards, all under contract from the Japanese government, to help develop or transfer new technology. So it was logical, even predictable, that with this new piece of technology, the pinnacle of British boatbuilding, an engineer from distant Europe would see to it.

Aritomo scolded himself for his first, disapproving reaction.

Without the British – and other friendly European powers – the imperial fleet in its present form wouldn’t exist. That might seem like a blemish, but it was also a fact. The engineer from the British Empire was a help, not a threat. He had to keep that in mind. The man was here, because the Admiralty thought it necessary.

Aritomo Hara wouldn’t question that decision.

He took a deep breath. They were all complete. The big moment was imminent.

The Prince positioned himself as was expected of him but seemed strangely inconspicuous, almost shy. Instead of saying something by himself, his teacher took the floor. Aritomo only half listened to the speech. The old man greeted the soldiers and thanked them. He pointed out that the Prince was aware of the conditions aboard the boat and that careless touch or other afflictions wouldn’t be construed as offensive or unruly behavior. He expressed his hope that the maiden voyage would be free of problems and praised the soldiers for their service. A little speech that should serve as general reassurance. Aritomo was astonished to find that, in spite of his superficial attention, it was effective. He felt a bit more relaxed and could recognize subtle signs of relief among his men. Everyone had been afraid of making a nasty mistake unintentionally, fatal in the immediate vicinity of such an exalted person. The visitor was obviously aware of this fear and had tried to do something about it.

Aritomo frowned involuntarily.

Why did a cadet, who lived and learned at a cadet school from morning to evening, actually need a private teacher?

He looked at the young Prince, who stood beside his mentor, his face uninvolved, neither approving nor rejecting, but listening just as stoically as the tight-shouldered soldiers. For a moment, however, he looked up, moving his head slightly and glancing at the men’s line, stopping briefly at the eyes of Aritomo, highlighted by his position at the quayside and his officer’s uniform. Their eyes didn’t meet for a long time, but for the officer, that moment was rather unpleasant – and not because of a sudden reverence or some of the fear the teacher was trying to dispel.

But because he had the impression that this look of the young prince had been so terribly … empty.

Aritomo blinked. Inugami barked an order. The boat was to made ready. All men were expected at their stations before the guests arrived. No risks. Immediate haste commenced.

Aritomo scared away the thought he had just had. He was foolish. Presumptuous. Nothing that had to occupy his brain. His duties lay elsewhere, and he gratefully accepted that insight, concentrating on making that journey of his beloved boat a great success.

For Japan.

For the Emperor.

For himself.

They gave him the tour. It was tight, it was slightly stuffy, and despite all the words of the old teacher, everyone felt a bit uncomfortable in the immediate vicinity of the Prince. The boat was a little over fifty yards long: the front-end torpedo room, the engine department with the diesel and electric motors, the close quarters of the officers – all the other crewmen slept as best they could at their stations –, the control room under the bridge, that one located on the tower, the middle torpedo room from which the boat could launch torpedoes sideways, and the small fair where heated food and tea could be cooked. After all, the boat was so wide that in some places up to three men could stand side by side.

The British engineer – Robert Lengsley was his name and he had behaved politely, friendly, even spoke some Japanese, indicating that he had been residing here for some time – stayed with Sarukazaki in the engine room.

After everything had been shown, Aritomo exhaled in relief. Lieutenant Inugami had performed like a rooster in a chicken coop, lost himself in endless explanations, almost giving the impression that he had constructed this boat on his own, built it with his two hands, and could navigate it all on his own if allowed to do so. That the young Prince had tolerated these eulogies with disciplined calmness, spoke for the young man’s capacity for suffering, an ability that possibly had its roots in the strict education at court. The old teacher had asked some polite questions in the beginning, but then realized that Inugami took every other question just as a reason for a fresh speech, and it was all too obvious that the man wasn’t very comfortable in the confines of the boat.

Inugami finally ordered, to everyone’s relief, that the boat should proceed on its voyage. The Prince wanted to watch this process outside, from the tower, which was universally accepted, because it meant that he and his companions would not contribute to the tightness aboard the ship. The commander himself insisted on accompanying the young man outside. Amazingly, the old teacher stayed down on in the control room. He seemed to consider the finiteness of the boat to be the lesser evil than having to endure Inugami’s lectures, and was visibly pleased when a cup of tea was served for him.

Aritomo bowed to the old man. “I hope the boat doesn’t get too cramped for you, esteemed teacher.”

“My name is Daiki Sawada, Lieutenant. I would be glad if you simply approached me as Mr. Sawada. The never-ending kowtowing is somehow misplaced in such a limited space. You bump easily into each other.”

Aritomo smiled and bowed again. “Of course, Mr. Sawada. Your student seems to be very docile. He listened attentively to the lectures.”

The old man’s gaze faded a little, as if searching for the right answer to this claim. His distress was ended by loud orders from above. There was not much to do on the bridge. Only the helmsman relayed the commander’s orders to the engine room. The soft vibration of the diesel engines filled the body of the boat as it drifted away from the quay with majestic composure – or great caution, depending on the point of view – and then slowly started up. It was not an exaggeratedly cool morning, so the wind was certainly been bearable at higher speed, and Inugami evidently linked the departure with a small harbor cruise for the Prince.

Military music was audible from the quay, and the honorary company shouted with vigor: “Banzai!”

Aritomo closed his eyes for a moment, feeling the subtle movements of the boat under his feet and the potential, still restrained, a dormant power at their command. It was an uplifting feeling and worth all of the effort.

The weather played along. The sea was calm. Aritomo looked at the instruments in front of him, the diesel engine tachometer, the compass, the speedometer. He could feel the quiet sound, the perfect position of the boat in the water. Everything went so well together. It was a marvel of technology.

“All the writing here is in English,” muttered Sawada, as he studied the endless array of controls and levers and buttons that covered the wall, watching the work of the helmsmen.

“Correct. On all ships of the Japanese Navy the descriptions and signs are in English,” Aritomo told him. “Most of our first ships were built by British shipbuilders, many of the consultants were British, and many of the first instructors as well. We have learned a lot from the Royal Navy, and that has been reflected in the fact that all our new ships continue to adhere to the English language. Every officer has to learn English, though many only learn the basics.”

Sawada looked inquiringly at the young man. “There are enough of us who still believe it is beneath our dignity to learn a foreign language.”

Aritomo nodded. “Yes, and many officers have joined this group. But we wouldn’t have a fleet if we hadn’t been able to absorb foreign knowledge. And we would only have enemies abroad if we refused to accept languages other than our own.”

Sawada smiled. “Contracts are often temporary.”

“You surely know more about these things than me. I am only a second lieutenant. I am executing the orders of those who know and guide us.”

“But I suppose, Lieutenant Hara, that you took your English lessons seriously.”

Aritomo nodded. “I took every one of my lessons seriously, Mr. Sawada. I come from a poor artisan’s family, and the naval career was a unique opportunity for me to do something different. I was the best student in the class and received a scholarship for high school. I was third in my year at the academy. I could have gotten an assignment on one of the big cruisers. But I wanted the submarines.”

Before the old man could say anything, they heard movement from above, and legs appeared on the ladder. Moments later, Inugami and the Prince had reached the bottom. They were followed by the two bodyguards who hadn’t said a word the whole time.

“Get ready for diving!” the commander ordered after he himself had closed the bulkhead. “Ready to blow out!”

There was no rush. Everyone knew what to do. They had an excellent crew.

Nevertheless, Aritomo felt excitement and tension, and he wasn’t the only one here.

They went down into the depth.

The boat was in its element.

And Second Lieutenant Aritomo Hara was too.

4

“We’ve reached a depth of 15 meters,” Inugami explained in a submissive tone to a quietly muttered question by the Prince. It was the first articulated question he had asked himself, instead of nodding to emphasize his teacher’s inquiries. Aritomo paid only marginal attention to the exchange. While the lieutenant was playing the tour guide, he was the first officer to oversee the boat’s journey. It proved difficult to entertain the guests and at the same time run a boat. In their division of labor Inugami had therefore focused entirely on the Prince and left the rest to Aritomo.

That was quite satisfactory.

The boat worked very well. The dive had gone smoothly. As soon as the tanks had filled with seawater, the diesel engines had stopped. Completely silent, the body of the boat had slid below the ocean’s surface, then the electric motors had been started.

“Does the Prince want us to resurface? Not everyone feels at home in the deep,” Aritomo heard the Captain’s question. The young man’s answering voice was hard to understand, but with no order to end the dive, it was likely that he would endure it for a while longer. If Aritomo got it right, glancing out of the corner of his eye, the Prince was anything but sad or frightened. His movements seemed more active since the boat has started its descend, his eyes were bright. The boy was excited about this technology and glad to see it in action. Aritomo began to warm himself for the Prince, because he could understand this childlike fascination quite well.

Aritomo looked around. All crew members radiated the calm competence of experienced submariners. All of them had served on the old Holland boats. By comparison, their new home would seem like a luxury to them, as spacious as a festival hall, and even with a proper toilet that shot feces out into the water with heavy air pressure. On the Holland boats, there had been no more than a bucket filled and dumped over the side of the ship when back on the surface. That wasn’t something Aritomo really liked to remember.

“We’re going to periscope depth now,” Inugami announced, giving Aritomo a meaningful look. But he had already taken action and whispered commands to the crew in the control room. It was barely noticeable how the boat reacted, obediently, without deviation, with a sense of elegance and security.

“Periscope depth, Captain!” Aritomo announced moments later.

Inugami pulled out the periscope and let the Prince glimpse for a while while he did nothing but look complacent. Everything went according to plan. If this trip was over, the admiralty’s gaze would rest with the utmost benevolence on Lieutenant Inugami.

“I can’t see much,” the prince said quietly, turning the periscope a little to the left and right. “It’s very foggy.”

Inugami gave Aritomo a confused look. “Fog, Your Highness?”

They had left in the late morning, with bright sunshine and a calm sea. When they had looked at the horizon one last time just before diving, there was no sign of fog far and wide.

“If you allow …?” Inugami asked, and the Prince stepped aside to make room for him. It took less than a minute, then the officer turned his eyes from the eyepiece and left it to Aritomo.

“We better return,” the Captain explained. “We don’t want to accidentally ram somebody. Few nautical miles away, the fog should have disappeared.”

Aritomo immediately recognized the meaning of Inugami’s order. In fact, the boat was surprisingly navigating in a dense soup. Where it had come from so unexpectedly and in the face of these weather conditions – that was very puzzling. Something like that had never happened to him before.

Here in relative proximity to the Japanese coast, there was a lot of busy shipping traffic. In fact, it was better to regain depth and avoid the danger of a collision. Not everyone took the regular operation of the foghorn seriously, and within the boat, one of those sounds could easily be overheard.

“Thanks for the valuable hint, Your Highness,” Aritomo kindly thanked him as he had retracted the periscope. The Prince hinted a smile. With that he suddenly looked very, very young, like a child he in a way still was, after all. The first officer refrained from further comments. He had no intention of competing with his superior for the imperial favor.

There was work to do, anyway.

The boat sank cautiously back into the depths. At about twenty meters they stabilized it, and the electric motors pushed it through the waters. Five knots weren’t a lot of speed but enough to keep the boat steady and slowly clear the area of the strange fog banks that had appeared so unexpectedly. Inugami had ordered to keep this course for half an hour, then reappear and observe. Although not actually dangerous, this change of plan created some tension among the men and gave the Captain the opportunity to demonstrate his leadership skills.

Aritomo frowned. There might be some tension but apparently not enough to keep the men awake. He watched as one of the helmsmen suddenly yawned and wiped his eyes. It was a bit too much for the first officer, and he gave the man a warning glance. Everyone was well-rested for this trip! But before he could say anything, Aritomo sensed that a sudden weariness overtaking him as well. Involuntarily, he ran his hands through his short-cropped hair and blinked.

Tea. He might need a strong tea. He yawned involuntarily, his gaze moving almost automatically to the carbon dioxide display. The pointer had not moved. But was the instrument correct?

He looked around. The same symptoms discernible with all men. Yawning. Blinking. The Prince was just now covering his wide-open mouth with his gloved hand.

Carbon dioxide poisoning! he thought. Inugami looked at him, the same realization in his eyes. Something had to be wrong with the air supply. The adrenaline animated him.

“Surface!” he ordered. “Immediately and hatches open!”

The boat trembled. The ballast tanks pumped the water out. Aritomo felt the bow tilt up, imperceptibly, and stared at the depth gauge. Fifteen meters. His eyes blurred. He wiped his eyes. Ten meters. He had to hold onto the wall against his will as his knees softened. So fast … no CO2 poisoning worked that fast.

This wasn’t normal. He felt so terribly weak, very dizzy, a little sick maybe …

He saw how Inugami swayed too. The old Sawada had already slumped to the floor, and the Prince slid down, clinging to the wall for a moment, as if to preserve some imperial dignity, uttering a soft, barely audible cry. Aritomo tried to fix his gaze on the depth gauge again. Five meters. The boat would break the water surface at any moment. If he only lasted long enough – or one of the other men – to open the hatches, at least one at the bridge … The fresh air would …

Aritomo’s thoughts swirled, and he lost all concentration. Inugami was lying on the ground, didn’t move anymore. The helmsmen sank over their instruments. With superhuman effort, he took a step toward the ladder leading up to the hatch, then clung to the rungs for a moment, forcing his eyes open, trying to ignore the dancing black veils.

He didn’t succeed.

He almost felt the boat emerge with gentle sweep, but then he lost all strength and sank unconscious to the ground.

There was no one on board to open a hatch.

Aritomo came to lie next to the Prince and was as quiet as everyone else.

5

K’an Chitam looked up the temple, wondering if it was worth it. The more than 30-meter-high construction was not finished yet, but that was not necessary. The numerous workers who worked under the supervision of the great architect Chaak had time. Their ruler, the mighty Siyaj Khan K’awiil II, King of Yax Mutal and descendant of Yax Nuun Ayiin, was not only alive but continued to enjoy good health. For Chitam, that was good news on many levels: It meant that his own coronation was still quite far in the future, and it meant that he continued to live, despite his court duties, a relatively carefree life. As the eldest son of the king, he enjoyed a number of privileges, including the fact that no young woman in Mutal could avoid his advances, a circumstance that the now 25-year-old prince used extensively, wife or not. As long as he fulfilled his other duties, he was subject to no further restrictions from his father, who was always busy with other tasks. With that, Chitam enjoyed a special privilege. Usually, adultery was not a matter that his people accepted lightly. But the heir to the throne was not only the next king, he was also a man with a sunny mind, always friendly, generous, witty and lacking the arrogance of many noblemen who consistently thought they were someone better.

Of course, Chitam was someone better.

He didn’t think he had to rub it in everyone’s face. And the beautiful daughter of a peasant was also much more inclined to approach his overtures with a certain passion, if he didn’t behave like an asshole but presented himself as a nice, good-looking, charming and powerful man who would be in charge in a few years.

One just had to put one’s qualities to good use.

K’an Chitam sighed and looked at the artisans around him, who pounded the stele stones with great care and fervor. Although his father, the king, was a direct descendant of that ruler whom the conquerors of distant Teotihuacán had appointed, he was now anxious to break away from the memory of this military campaign and its consequences, and to establish a truly local dynasty. Although there were still vague references to the origin and legitimacy of their rule in the stelae commissioned by Siyaj, it was also clear that the campaign had been more than thirty years ago, and no soldier from Teotihuacán had ever returned to Yax Mutal’s soil. It was therefore time to remember what was right in front of them and still very tangible. It was necessary to show the people that Siyaj and his son Chitam were rulers in their own right, chosen by the gods, and thus their mouthpiece and connection to the mortal world.

Chitam found this request of his revered father highly commendable, as he prepared the needed stability and respect for his son’s rule. But just this morning, after a night of drinking, in which the Prince, together with his friends, had consumed vast amounts of holy chi