Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

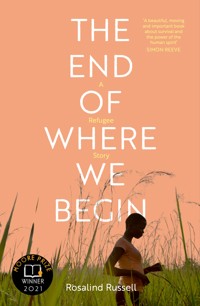

Winner of the Moore Prize 2021 'A beautiful, moving and important book' – Simon Reeve The gripping true-life story of three young people in the world's youngest country, South Sudan, whose lives are ripped apart by a brutal war. Veronica is a teenager when civil war erupts in South Sudan, the world's youngest country. Lonely and friendless after the death of her father, she finds solace in her first boyfriend, and together they flee across the city when fighting breaks out. On the same night Daniel, the son of a colonel, also makes his escape, but finds himself stranded beside the River Nile, alone and vulnerable. Lilian is a young mother who runs for her life holding the hand of her little boy, Harmony – until a bomb attack wrenches them apart and she is forced to trek on alone. After epic journeys of endurance, these three young people's lives cross in Bidi Bidi in Uganda – the world's largest refugee camp. There they meet James, a counsellor who helps them find light and hope in the darkest of places. In a gripping true-life narrative, Rosalind Russell tells their stories with uplifting empathy and tenderness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ROSALIND RUSSELL is a journalist and editor with two decades of international experience. She has worked as a foreign correspondent for Reuters and The Independent in East Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Her reporting included the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the war in Iraq and Myanmar’s Saffron Revolution. Her first book, Burma’s Spring, published in 2014, was described by Asian Affairs as “reportage at its best” and reached number one in the UK Kindle non-fiction bestseller list. She lives in London with her husband and two daughters, and currently works for the Evening Standard.

Praise for The End of Where We Begin

“Engages our hearts with vivid and moving stories…written with extraordinary clarity, compassion and impact”

Moore Prize 2021 Jury

“A beautiful, moving and important book about survival and the power of the human spirit”

Simon Reeve, broadcaster and author

“Insightful and deeply humane. With vivid detail, it captures the essence of life in South Sudan at a particularly turbulent moment in its history”

Michela Wrong, author of Do Not Disturb and It’s Our Turn to Eat

“A powerful and authentic account”

Luka Biong, author of The Struggle for South Sudan

“A captivating…compelling chronicle of the refugee experience of displacement, loss and hope”

Ka’edi Africa

“Powerful and moving…stays in your memory long after you have put it back on your bookshelf”

Publishing Post

“A harrowing and intimate account of civil war’s toll”

Kirkus Reviews

Published by Eye Books

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

Copyright © Rosalind Russell 2023

First edition published by Impress Books, November 2020

Cover design by Nell Wood

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro and Brother 1816 Printed

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher.

Rosalind Russell has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781785633713

For Ruby and Mattie

‘There is no story that is not true’

Chinua Achebe

Things Fall Apart

Contents

Author’s Note

Prologue

PART 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

PART 2

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Afterword

Resources and Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

In April 2023, news bulletins were briefly dominated by the eruption of civil war in Sudan and the race to evacuate foreign nationals from the city of Khartoum, which overnight became a lethal battleground between the army and a mutinous militia group. But once Western nations had airlifted their citizens to safety, the gaze of the world’s media quickly moved on, even with millions of Sudanese civilians uprooted and on the move.

The same scenario had played out with painful similarity a few years earlier, when convulsions of violence ripped through the capital of Sudan’s neighbour South Sudan, forcing hundreds of thousands of people to flee. I was working as a journalist in London on human rights stories, filing reports of the sudden and dramatic exodus. Civilians were streaming across the border into Uganda on a scale not seen since the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Over the following months, Bidi Bidi refugee camp in Uganda, a city of sticks and tarpaulin, grew to become the largest in the world, home to a quarter of a million people. Aside from the occasional article here and there, however, the scale of the crisis and its terrible human consequences were barely touched upon in the media.

This was a region I knew from my years as a correspondent for Reuters in East Africa when I reported from South Sudan on its struggle for independence. My life was settled and my daughters were still in primary school, but I felt the pull of my old life as a foreign correspondent; I wanted to return to the region to document the stories behind these astonishing numbers.

I first arrived in Bidi Bidi in February 2018 on the back of a motorbike driven by a Ugandan mental health counsellor, James. He worked for a small charity that struggled to pay for the fuel needed to run their battered four-by-four vehicle around the five zones of the sprawling camp. Bidi Bidi, in the north-western corner of Uganda, covered a hundred square miles and took two hours to traverse along dirt roads and rutted tracks. Its low hills were dotted with tarp-roofed shelters, newly built mudbrick homes, acacia and neem trees.

Only registered refugees were allowed to stay overnight in the camp – or settlement, as it was known, as it had no fences or boundaries. The camp commander signed and stamped my clearance letter to visit in daytime. I stayed in a guest house in the small trading town of Yumbe, which was booming following the arrival of hundreds of mostly Ugandan aid workers recruited to help in the crisis. The aid agencies War Child, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee, World Vision and TPO helped me with transport and access, allowing me to spend several weeks in Bidi Bidi and later Rhino Camp and Nyumanzi settlement. The Franciscan Brothers kindly hosted me at Adraa Agricultural College in Nebbi where South Sudanese refugees had been enrolled on short courses.

All the people in this book and the events they describe are real. The main three characters –Veronica, Daniel and Lilian – asked me to use their own names, but I have changed the names of some family members and others to maintain the confidentiality of those who were unable to give their consent. The stories are drawn from extended in-person interviews conducted in 2018 and 2019 in northern Uganda and South Sudan and, after that, from many conversations by phone, WhatsApp, Facebook messenger and email. Daniel and Lilian spoke to me in fluent English. In interviews with Veronica I at first relied on Save the Children staff, or her neighbour Wilbur to translate from her native Arabic. But when I met her alone I discovered her English was really quite good and we were able to talk without an awkward male presence.

With introductions from aid workers and officials who supported me in the camp, I interviewed more than fifty refugees over several months and heard many stories, often heroic and heart-breaking, which have been hard to leave out of this book. The characters who form the heart of the narrative stood out, as not only did they have remarkable stories to tell, but they were keen to tell them. They were willing to accept me into their homes, allowed me to follow their daily routines and patiently answered my endless questions. This means they are perhaps not a representative sample, but I am confident that their lives, while extraordinary, were typical in the context of the camp. Similar tales of loss, courage, compassion and ambition were repeated over and over. Important, harrowing detail was often relayed in a brutally matter-of-fact manner or quickly skipped over as it was considered so mundane. The lives I have explored in the pages that follow are snapshots of a far wider refugee experience.

These are not my stories. Despite some authorial interventions to provide political background and context, I have chosen to remain absent from the narrative and I have tried to write closely from the protagonists’ perspectives. I have attemptedas far as possible to replicate the inner thoughts of my characters as they described them to me. I do not know what goes on inside their heads but I have tried to construct a realistic narrative from their descriptions of their journeys, conversations, emotions and life events. The intimacy of some of the accounts reflects the startling openness and generosity of Veronica, Daniel, Lilian, Asha and others during our conversations. It’s hard to over-estimate their courage and generosity in speaking to me. While all the dialogue in the book comes from their own descriptions and accounts, I have sometimes used literary licence to reconstruct experiences or interactions and I have also had to alter the chronology of some personal events in order to give the narrative shape and momentum.

I documented the experiences of the refugees with written notes, audio recordings and photos and video. In the course of my reporting I also spoke to aid workers, community volunteers, teachers, health workers, religious leaders, government officials and UNHCR representatives. I was helped with fact-checking by Christine Wani, a journalist and South Sudanese refugee living in Bidi Bidi. I visited the South Sudanese capital Juba in October 2018 to research the events described in the book and better understand the environment from which the refugees fled, where I was assisted by the Reuters correspondent Denis Dumo. I have also relied on news articles, human rights reports, publications by academics and researchers and books about South Sudan’s civil war.

The title The End of Where We Begin is derived from a Dinka blessing to the Earth. In the context of this book, however, it illustrates the injustice of young lives brutally interrupted by war. While the rightful expectations of these three young people have been snatched away, I hope that in illuminating their search for meaning and opportunity amid extremes of violence and exile I challenge the often stereotyped narrative of refugees. The following pages explore the consequences of civil war in a fragile African nation, but although specific to a time and place, I hope the stories of Veronica, Daniel and Lilian resonate beyond the confines of the refugee camp where I met them.

There is a boy in the camp who always walks around with his head tilted to the left side. It looks uncomfortable, as if it is seized up in that position. The boy is young, but old enough to look after himself. He never goes to school; mostly, he sits under the mural of the dancing children and the dove of peace in the dusty, disused playground, next to the water tap. He likes to watch the women filling up their containers. Their infants, strapped to their backs, sometimes start crying because the boy looks so weird. It’s tempting to try to straighten him up, maybe massage his neck and shoulders, relieve the tension. Just looking at him makes everyone feel tense. When anyone asks him why his head is askew like that – they rarely do – he answers calmly and politely. To him, his explanation makes perfect sense.

In South Sudan, he hid in a tree when the soldiers came. He lay flat on a good, strong branch, quite high up among the leaves, and made his breathing go quiet. It was hard for him to stay quiet when he watched the soldiers slaughter his family – his grandmother, mother, father, older brother and younger sister – but he managed. He listened in silence to the screams of his loved ones and the soldiers’ shouts and laughter. He clung to the tree all night. He kept still for hours, even when he had to relieve himself. He didn’t sleep. He had to be sure the soldiers had gone.

In the morning, he climbed down. When he reached the ground, his legs buckled under him, they felt prickly and numb. He stumbled over to his mother’s body and lay down beside her, face to face in the dirt. Her eyes were open and staring. He waved away the flies and stroked her cheek and hair. She still wore the delicate string of coloured beads around her neck. It was getting hot but she was cool; he had never felt a person like that. He stayed there for a while, he might even have dozed off, but when the sky darkened above him, he bolted up. Birds were swooping down, flapping their great wings for balance. They were big, ugly birds and they started to peck at a wound in his big brother’s flank. The young boy let out a scream. He jumped up and with flailing arms ran at the vultures, stumbling over the bodies of his family. The birds took off, squawking, their wings fanning the warm, putrid air. They circled above. The boy ran into the house to look for blankets or sacks to cover the bodies. But the soldiers had upturned their home; everything was gone. He ran to the cassava field to see if the spade was in its hiding place, halfway up the third furrow. It was there.

As the sun blistered down, the boy dug a grave for his family. At first, he kept running back to the bodies to shoo away the birds, but he could not do both. He dug and dug, his body dizzy, the sound of his panting in his ears. He must have fainted, because he opened his eyes to find himself lying in the grave. It still wasn’t deep enough; he had to keep going. Shovel, throw, shovel, throw. The soil was red and dry. Sweat trickled into his mouth. The sun plagued him all day, dipping and cooling only when he had dug a hole big enough to fit five bodies. Well, he hoped it was big enough; he had never dug a grave before.

He went back to where the bodies lay. It had started to get dark. The boy’s eyes were wide and alert, but he didn’t see the mutilated corpses in front of him, because that would have killed him too. He saw his family: his grandmother, his mother, his father, his sister, his brother. With them, he had spent fourteen perfect years on this earth. He liked to say this, when he got to the camp, if people asked.

Now he is committing them back to the earth. He begins with his grandmother, the lightest. He kneels down beside her, unsure of how to pick her up. He turns her on to her back. He sees her gentle, weathered face. He turns her back on to her front. He needs to get some purchase. He burrows his right shoulder down under her waist, reaches under her body to her right arm, clutches it, and tries to stand. His skinny legs wobble like a newborn calf’s. He adjusts his grandmother’s body on his shoulder and brings his left arm behind his neck to steady the load. He staggers with her across the family homestead to the new family grave. He returns four more times. It is dark when he covers the bodies with the soil.

“I carried them on this side,” he tells people in the camp, patting his right shoulder; his head crooked awkwardly to the left. “They were many and they were heavy. That’s why I can’t put my head straight now.” He is usually smiling, but his eyes are blank. “Sometimes I hear them calling for me. They want me to come back. They are too squashed in.”

The boy pats down the fresh grave with the back of his spade and lays down on top, sprawled like a starfish. He listens to the throb of the crickets and the soft wind in the leaves. It is peaceful. He wants to close his eyes and fall asleep. But also, he wants to live.

He hauls himself up and starts to run.

PROLOGUE

With the first hint of dawn the camp begins to stir. The darkness fades and the small, twittering birds that share this desolate, unsatisfactory home with a quarter of a million refugees launch into their feeble chorus. A pale, violet light seeps through the cracks around the door toLilian’s one-roomed home and slowly her eyelids open. Another day. She sits up on the narrow iron bedstead, plants her feet on the dirt floor and steps straight outside in her nightdress. The jumbled remnants of a dream slip away as her muscle memory walks her, barefoot, to the water tap.

Things move slowly in the camp. Time and money, the twin engines of life elsewhere, aren’t so important here. There are hardly any jobs and very little cash. It is always hot, so no one rushes, but there are still certain chores that need to be done. At the water pump, neat lines of yellow plastic jerrycans radiate from the single tap like sun rays in a child’s drawing. Lilian sets down her container at the end of a row. Dozens of women have got there before her. The tap won’t be switched on until seven, and they have scratched their initials onto the containers so they can come back to claim their places once they’ve got the cooking fires going.

Lilian lives by herself in the camp, but she hasn’t always been alone. She was married at nineteen and she and her husband had a beautiful baby boy. In South Sudan she had a job she loved and a vegetable garden where she grew cassava, maize, groundnuts and beans. Now, six years on, she has lost her husband, her son, her house and her land. She could blame the war for that, but actually she blames herself. This is an issue she needs to work on, her counsellor has told her.

She walks back home with her friend Asha. The two young women, tall and lean, stroll towards the rising sun, responding to its nurturing warmth like flowers, standing straighter, tilting up their chins. Lilian feels wonder that she can do this, live another day, go on. She doesn’t understand why she is still alive, why she fetches water, sweeps, cooks and talks to her neighbours. But something is driving her forward.

“So, are you serving today?” Lilian asks her friend.

Asha is a quiet, industrious woman. She has started her own business in the camp selling her home-brewed maize liquor; she half-starved herself to get the seed money but now it’s paying modest dividends, for which she thanks God because she has just found out she has a baby on the way.

“Yes, but I only have two bottles left. I’m closing before counselling starts,” Asha says.

“Those men will be disappointed!” says Lilian, talking about the drinkers who assemble under the tree as the sun starts to get hot. Asha serves them her powerful, fermented brew in plastic mugs and they talk and laugh and fight and usually fall asleep, half propped up on the knots of the tree roots. Asha wakes them when it’s dark and sends them home. “How about,” suggests Lilian, “after we’ve finished today, I’ll help you with the next batch.”

Asha smiles at her friend. It’s rare to see Lilian in such good spirits. They set down the water drums next to the beaten metal doors of their adjacent mud-brick homes and Asha hears Lilian softly humming as she starts to prepare the porridge that must sustain her until tomorrow.

Today is counselling day and, although they would never say so, they are both looking forward to it.

Daniel is sitting on the bench he has made, leaning back against the warm clay of the shady side of the house. He is idly strumming his guitar, more from habit than enjoyment; he knows that no one really wants to hear him play. He watches his mother and sister. They are squatting next to two basins of water. His mother is washing their clothes with a bar of laundry soap, handing the items to Tabitha, his sister, who rinses and wrings and hangs each piece up on the line. Daniel watches the woodsmoke drift up and cling to the wet clothes; everything will smell worse than when they started, he thinks, but says nothing. He admires them, he really does.

He can’t believe he’s here, back in a refugee camp. He feels safe again, but that is the only positive. He and his sister grew up in another camp, in Kenya – that was when they thought their father was dead. It was only when he reappeared and they started a new life in South Sudan did Daniel realise what life in a refugee camp had meant: rules, restriction and, worst of all, stagnation. Some people like it, the boundaries and the certainty, but Daniel isn’t one of them.

He has an appointment today, such a rare occurrence he must be careful not to forget to go. There is so little to punctuate their lives, it’s easy to lose track of the days. He’d love to have a calendar, like the one they used to have with pictures of a happy family drinking Ovaltine. The father in a work suit, a smiling mother and two healthy children, a boy and a girl, both smart in their school uniforms. They looked so clean and happy. Daniel’s family had kept it for years afterwards, turning it back to January at the start of each year and going through the months again just to see the pictures, the days were all wrong. But anyway, his appointment, his next session of counselling, is definitely today, Tuesday, two days after Sunday which is the only day that’s different in the camp. That’s the day they go to the open-air church with the tree log pews and his mother tries to get her hands on some cabbage or onions to distract from the monotony of their food rations.

A couple of months ago Daniel was given a questionnaire from one of the aid organisations. They were worried about the refugees, because of all that they’d been through. They wanted to help everyone, especially the ones who had seen the worst of it, to stop them from going mad. Daniel filled in the questionnaire and he really enjoyed it; no one had ever made such enquiries about his well-being, his sleep patterns, his health and his feelings before. Some of the things they asked he had never even considered. He’d never been encouraged to dwell on his emotions, or even acknowledge them, so holding that biro and going through the whole survey was a real novelty, and in some ways, a relief.

It was tempting to skew the answers. He thought he knew what they were looking for, what would get him onto the treatment programme, but he tried to be completely honest. Some of the questions made him think about things he had never thought of before, or made him feel upset.

Did he sleep badly, were his nights full of terrors? Yes. If it wasn’t the fighting in Bor it was often the bus crash and the faces of his school friends. Did he isolate himself from others? He hadn’t thought about it like that, but on consideration, yes. Was he emotionally short-tempered? His mother would say so. Was he depressed? He didn’t know what that meant. Did he suffer from headaches? Body aches? Yes, but that was from the accident. Did he ever feel suicidal? That question just made him feel guilty, unworthy. Only people who had really suffered badly could think of something like that. What he’d been through was just the same as everyone else.

Veronica is wearing her stripy top. It has wide brown, orange and white stripes. It’s actually a child’s top, but it’s made of stretchy material. The sleeves reach just past her elbows and the curve of her belly shows above the waistband of her skirt but it still looks good. Veronica looks good in anything. She is long-limbed and graceful, her skin luminous, her head shaved, her face perfection. Veronica is the seventeen-year-old mother of two-year-old Sunday, who has come with her to the group counselling session. The little girl wears a grubby ivory-coloured nylon party dress – a cast-off from another child in another world. She loves the dress, but the material makes her skin itchy when it’s hot.

The sun is burning through the white canopy of the tent’s roof – sheets of white UNHCR tarpaulin stitched together. Veronica, the youngest in the counselling group, is sitting on a plastic mat and the other women are clucking around her. They are kind, she thinks, she doesn’t feel judged, like she usually does.

“Sunday! Sunday!” they call, delighted by the round-cheeked toddler who runs around the circle of women sitting on the floor. There are two men in the group too; they are standing, waiting for the session to start. The little girl stumbles and falls, carefully picks herself up from the bare floor, checks her dirty palms and sets off again.

“So, when are you expecting the next one?” asks the woman sitting next to Veronica. Although Veronica hasn’t told anyone about her pregnancy, her slender frame means it’s impossible to hide. What she really wants is to go back to school, but she’s not sure how that will work, with Sunday and the new baby. She fiddles with the silver crucifix that her father gave her at her Confirmation when she was eleven years old.That seems a long time ago now.

“In May,” Veronica, almost whispers in her soft, dreamy voice. “It will be raining by then.”

To her relief, further enquiries are curtailed by James the counsellor who claps his hands to get the session underway. They all look up. Each one of them, for their own reasons, is keen for this to work. He claps out a rhythm, which Veronica and the others duly repeat. It’s to wake them up, help them concentrate, he says, pacing around their circle, exuding his usual enthusiasm. This is session eight of the programme and today, he tells them, they will continue to share their most difficult experiences with each other – but only if they want to, of course.

A faint line forms between Veronica’s eyebrows. She’s not sure if she has the confidence to speak today. She struggles in this kind of environment. Sensing the change in atmosphere, Sunday toddles back to her mother and plants herself on her lap. Veronica puts her arms around her daughter and dips her head so the little girl’s soft cheek rests against hers.

Lilian, the woman who always wears a yellow dress, passes around sheets of paper. They are handouts from James, to help them understand their feelings. Lilian likes to look for these jobs to do, Veronica has noticed. Last week, Lilian told the group how she lost her little boy when she ran from South Sudan. They had been caught in a battle, and everyone had been separated. She has no idea if he is dead or alive. Although Veronica has her own problems, she felt the aching emptiness of this woman’s grief. She cried when she heard that story.

“Can you two share one?” asks Lilian, licking the end of her finger and separating a white A4 sheet from the pile. She smiles at Sunday, who is now sitting quietly in her mother’s lap, examining her fingers. Veronica thanks her and accepts the piece of paper, watching Lilian’s smile drop as she moves on round the circle.

PART 1

Chapter 1

Veronica

2012

It was after her father died that Veronica got into bad ways. She had been a few months off twelve, with two younger brothers and a little sister. She had always thought she looked like a boy, like her brothers Santino and Simon. She had wanted to grow her hair, to have braids like some of her friends, but they were too poor for hairstyles, her head was always shaved. Now, more than a year later, she looked less like a boy. Her bones ached from the growing she had done; her hips were too wide for her old school skirt and she had had to dip her head to get through the low door to their dingy house. In class, she noticed her teacher’s eyes fall on her small breasts; she hated that, and she hated the painful stomach cramps and the shame of her monthly bleeding.

Her father had been a soldier, but he was off duty when he was killed. It was a robbery, on the road outside Bentiu, the town where they lived. That’s where they found his body. He was part of the liberation struggle and had been a rebel fighter in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army all of his adult life. But he never got to see the prize for which he’d fought for so long: he died in early 2011, just a few months before South Sudan finally won its independence.

Her mother hadn’t coped. With no earnings from their father, the family ate stewed okra every day, and every day with less salt. Veronica’s little sister Amani cried each evening, lying on the bed they shared. Their mother was a soldier too. She had met Veronica’s father in SPLA ranks and stayed on after the peace was signed, working as a cook. But her income was a pittance, and even with the goat bones and vegetable scraps she sometimes brought home from the barracks, the family was hungry.

At home, Veronica spoke less and less. At school, with her friends, she was okay, she didn’t discuss her father, the situation at home, or anything like that. Her friends didn’t talk about their own domestic problems either. At break, the girls still enjoyed their skipping songs, or they sprawled under the big tree, scribbling in their exercise books and talking about silly things; it was a place where they were happy. On the evening her mother told her they would leave and go to Juba to look for money, food, a job, Veronica said nothing. She walked out of their thatched-roofed tukul, grabbed an empty jerrycan and marched to the well, trying to recall her father’s voice. She let her tears fall down her cheeks. The neighbour’s children stood and stared.

“Veronica! Wait!” The boy was calling her. “Wait! Why do you always walk so fast?”

They were in front of the classroom with windows of wire mesh that let in the traffic dust, the fumes and the constant noise of the unfamiliar city. Juba wasn’t much for a national capital, but to Veronica it was overwhelming. In Bentiu she rarely saw a face she didn’t know; here everyone was a stranger. Men with reeking breath and yellow eyes leered at her on her way to school. In the market she was swindled by the water-seller and felt so ashamed she let herself go thirsty for a week. Their new home was a tin-roofed shack that their mother padlocked them into every night. At school she was behind in all subjects. The girls giggled at her heavy Arabic tongue, made faces behind her back and decided not to be her friend. The boys had mostly ignored her, except for this one. His name was Jackson.

“Will you be at church on Sunday?” he enquired. Veronica didn’t look at him, but she could feel the heat of his attention. She fixed her gaze on his ankles exposed by his too-short navy school trousers. His shoes were old black slip-ons, a cast off from an older brother, or a second-hand purchase from the market.

“Yes, as usual,” she replied sharply, switching to Arabic to answer the question posed in English. English was the language of instruction in the Juba schoolroom and one of the many things that made Veronica feel like an outsider in this city. She was too shy to speak it; it felt alien on her tongue.

“Good,” said Jackson, switching back to English. He leaned forward, but not too close. Veronica still refused to look at him. “I’ll see you there.”

Veronica had no idea why Jackson was interested in her. Her beauty was something she had yet to fully understand. People had told her she had inherited her mother’s looks, her smooth forehead, almond eyes with a silver waterline and her wide, transforming smile. In Bentiu, Veronica’s uncle had once remarked that she would be worth at least ten cows. Jackson was tall and lanky. He smelled sweet; he didn’t have that stale odour of the other unwashed boys. He was Nuer, like her, and Catholic too; he wore a small silver Virgin Mary pendant around his neck on a leather cord. He was fourteen, a smart kid, already in Primary Five. Veronica knew there were plenty of other girls at school who might be flattered to be singled out by Jackson, but to her, the attention was excruciating.

Even her poorest friends – the ones who would sometimes go days without eating and slept on the wet ground in the rainy season – had some sort of Sunday-best clothes. Veronica’s own church outfit – a white blouse, a short, candy-pink jacket and matching skirt with a thin plastic belt – had been the same for two years. The zip on the skirt was now a struggle to fasten and the hem was too high. She had some black court shoes with worn heels that her aunty had passed on and the silver cross that her father had bought forher Confirmation, when her whole family had sat at the front of the church. They had never been rich, but looking back, things had been easier then.

The Mass started at seven thirty in the morning, but it was acceptable to come later and the cavernous St Joseph’s in Juba took more than an hour to fill up. By the start of the main sermon, ushers wearing white tabards had to escort late arrivals down the aisles and ask those already seated to scoot up on the crowded wooden pews until thigh was firmly pressed against thigh. Veronica was squashed between her brother Santino and a large lady to her right who was fervently mouthing passages from her Bible, even as the purple-robed priest addressed the congregation, reminding them of the parable of the talents, exhorting them to use their God-given gifts in the service of the Lord. Heat and sweat built between their adjoining limbs as the service reached a noisy, happy crescendo. The choir sang songs praising Jesus, the words projected onto the screen above the altar so they could all join in. Apart from a scratchy radio blaring in the market, the only music Veronica heard was through the booming PA system at church, and this was one of the reasons she looked forward to Sundays. She was beguiled by the harmonies of the choir, the soft-rock solos of the guitarist and the soothing promises of deliverance from her family’s earthly challenges. She would sway to the Gospel beat, pricks of sweat forming on her nose, and lose herself in the message of love and hope. She always left church with a feeling of being scrubbed clean and a resolution to be a better child of God that week, more virtuous and devout.

She walked down the steps to the gravelly area under the bell-tower where the congregation mingled and chatted as the sun grew uncomfortably hot on their heads. She clutched her little black Bible and the silky drawstring bag with the pearl embroidery that she always carried to church, but which contained nothing. She stood close to her mother, holding her little sister’s hand. Veronica looked like she was listening politely to her mother’s cousin, also a migrant from the north, but her cheeks were burning and she was finding it hard to concentrate on the woman’s complaints. To her left, just in her sightline beyond another group of churchgoers, was Jackson, smart in his suit. He was staring straight at her.

It was partly her loneliness, partly his persistence that eventually sealed their friendship. He was the first male confidant she had ever had, and proved to be a good listener, especially when, after a few months, she was able to talk to him about her father. She talked about what had happened for the very first time, because her father’s murder was never mentioned at home; his absence was only referred to in the context of their straitened circumstances.

Jackson, two years ahead at school, also started to help her with her homework. Veronica struggled with the basics of writing and arithmetic. The sudden move to Juba had given her a fevered head, she told Jackson, and everything she had known from school had slipped away. She had failed to move up from P3 to P4 last year, and if she failed the end-of-year examination again, she would find herself in the same class as her younger brother.

“So, what is a fraction?” Jackson asked in his gentle, serious teaching voice.

“A fraction is a quantity that is not a whole number,” Veronica replied, confident when asked to parrot a phrase often repeated by her teacher.

“And different fractions can have the same value, is that correct?” he probed.

She scanned his eyes for the right answer.

“Yes,” she guessed.

“Good. So now you can place these fractions in order.”

The numbers he had carefully written out in pencil on the spare pages of a used exercise book swam before her eyes: two over three, one over four, four over six.

They were lying flat on their bellies, propped up on their elbows on the rubber mats of the after-school club, their heads together but their bodies at a right angle – any closer and they would attract the attention of the adult monitor. They were wearing their white school shirts, he with his tatty trousers and she with her thick, pleated skirt. Veronica waggled her heels distractedly in the stuffy heat. This was the only place they could meet and relax in Juba, a “child-friendly space”. There had been nothing like it in Bentiu, but aid agencies had piled into Juba since independence, each with an idea of how to help war-shattered South Sudan to its feet. The aim of the centre was to give children a protected area away from school to play and socialise, to help their rehabilitation. At thirteen, Veronica didn’t know this. Later she would become more expert in the lexicon of aid and disaster – she would learn about food distribution points, shelter kits and nutrition centres. For now, she was grateful for the breeze-block building, its walls painted with colourful murals, for the paper and pens that were sometimes provided, the quizzes and the games, and spending time with Jackson.

She wriggled her hips to move up the mat and get a bit closer to the book, so her head was right over it, the numbers right under her face, but it didn’t seem to help.

“I know,” said Jackson, “I have a big, juicy mango. I can cut it into three and give you one piece or cut it into four and give you two pieces – which one do you want?”

“But that’s easy!” Veronica smiled. Everything was easier with Jackson.

Chapter 2

Daniel

December 2013

Daniel always felt like someone in South Sudan. It was because of his father, of course. At boarding school in Uganda he was popular enough, but his unusual height, gappy front teeth and weird accent marked him out as an outsider. On the juddering bus ride home for Christmas, he sat alone by the window and watched the gentle curves and green tobacco fields of Arua county give way to a harsher landscape of rocky scrub dotted with desert trees as they drove towards the border. A bag of charcoal was jammed against his thigh; he was penned in, ignored. He dutifully performed the task of slamming shut the sliding window when an oncoming vehicle was sighted, to keep out the gritty red dust that flew up from its wheels, then opening it again when the air had cleared. No one acknowledged his efforts. At the border post, after presenting his new, eagle-crested