Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

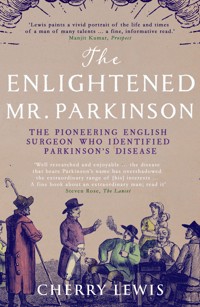

'Billy Connolly says he's no idea who Parkinson was and just wishes he'd kept his disease to himself. He should read this book.' Jeremy Paxman Parkinson's disease is one of the most common forms of dementia, with 10,000 new cases each year in the UK alone, and yet few know anything about the man the disease is named after. In 1817 - exactly 200 years ago - James Parkinson (1755-1824) defined the disease so precisely that we still diagnose it today by recognising the symptoms he identified. The story of this remarkable man's contributions to the Age of the Enlightenment is told through his three passions - medicine, politics and fossils. As a political radical Parkinson was interrogated over a plot to kill King George III and revealed as the author of anti-government pamphlets, a crime for which many were transported to Australia; while helping Edward Jenner set up smallpox vaccination stations across London, he wrote the first scientific study of fossils in English, which led to fossil-hunting becoming the nation's latest craze - just a glimpse of his many achievements. Cherry Lewis restores this neglected pioneer to his rightful place in history, while creating a vivid and pungent portrait of life as an 'apothecary surgeon' in Georgian London.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The ENLIGHTENEDMR. PARKINSON

The ENLIGHTENEDMR. PARKINSON

THE PIONEERING LIFE OF A FORGOTTEN ENGLISH SURGEON

CHERRY LEWIS

Published in the UK in 2017 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia by Grantham Book Services, Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City, Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-178578-178-0

Text copyright © 2017 Cherry Lewis

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Stempel Garamond by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

CONTENTS

Parkinson family tree

Prologue: A hole in the head

1. Living and bleeding in London

2. The hanged man

3. Fear of the knife

4. The radical Mr. Parkinson

5. The Pop Gun Plot

6. Trials and other tribulations

7. Dangerous sports

8. A pox in all your houses

9. The fossil question

10. A sublime and difficult science

11. ’Tis a mad, mad world in Hoxton

12. The name of the father, and of the son

13. The shaking palsy

14. Reforms and rewards

Epilogue: A fragment of DNA

A few words of thanks

Notes and references

Bibliography

Picture credits

Plates

Index

PROLOGUE

A hole in the head

English born and bred … forgotten by the English and the world at large – such is the fate of James Parkinson.

Leonard Rowntree, 1912James Parkinson

THE PATIENT LAY on the operating table with his shaved head clamped to a frame to hold it completely still: a necessary procedure since other parts of his body shook with uncontrollable tremors. He was wide awake and looked extremely nervous as the surgeon started boring into the top of his skull with a drill similar to one used by a dentist. Having made the hole – about the size of a five pence piece – the surgeon pushed a fine probe, three inches long, deep into the patient’s brain. When it touched ‘the spot’, it was the first time the patient’s limbs had stopped shaking in eight years.

While the description of this terrifying procedure sounds like it might have been written 200 years ago, the operation was in fact first performed in 1987 and marked a pioneering breakthrough in medical surgery to control Parkinson’s disease.1

Mike Robins’s problems had started ten years previously with a twitch in his right shoulder. Within a few months it had become an uncontrollable tremor down his right side and he was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. ‘I was put on medication, different combinations of tablets, but nothing really worked, and there were a lot of side effects,’ Mike said. ‘The only alternative to medication, I was told, was surgery, which although it was in its infancy, the results to date had been encouraging, and I was prepared to try anything that might improve my symptoms.’ Most patients suffer debilitating side effects after they have been taking medication for about five years. These effects include dyskinesia (violent writhing), hallucinations, psychosis and depression, and they can often be worse than the disease itself. Mike felt that anything was better than the hell he was going through with the drugs and decided to face the operation, even though he would have to remain awake throughout.

Deep brain stimulation, as the operation is called, is now widely used to alleviate a variety of movement disorders, although the majority of operations are carried out in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. The patient needs to be awake to help guide the placement of the electrode to the area that abates the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, as well as to monitor any untoward effects as the probe moves through the brain. ‘When the probe was passing certain parts of my brain, I saw colours brighter and more intense than ever before. When it moved to the area that controls speech I had to keep talking, so that the team would know instantly if anything was wrong,’ Mike explained. ‘Then the surgeon said there were just a few more millimetres to go, and as soon as he touched the correct spot – an area of the brain about the size of a cashew nut – my right leg and my right arm stopped shaking immediately.’

Once the implant has been placed in the brain, a battery-powered neurostimulator is positioned under the skin near the collarbone; it connects to the implant via a lead that lies under the skin of the scalp. The neurostimulator sends a mild electrical current to the tiny device which delivers electrical stimulation to an area of the brain that controls movement and muscles, known as the subthalamic nucleus. The electrical stimulation modulates the signals that cause many of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mike uses a gadget like a TV remote handset to control his symptoms: when he switches the stimulator off his arms immediately begin to shake so violently that he can hardly get back to the switch to turn it on again. But when he does, the tremors stop instantly. A video of him can be found online; it is very poignant to watch.2

Parkinson’s disease is one of the most familiar of all neurological disorders and the second most common neurodegenerative condition after Alzheimer’s disease. Worldwide, there are about 6 million people with the condition and at least 10,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in Britain alone. More common in the elderly and in men, approximately one in a hundred people over the age of 65 will get Parkinson’s disease. As our ageing population lives longer, more and more people will be affected.

It is a terribly debilitating condition. The main symptoms are severe tremor, muscle stiffness and slow movements, and diagnosis is usually based on the presence of two of those three symptoms. There are, however, other common symptoms such as a tendency to fall forward, which leads to a running motion when the patient intends only to walk; problems with communication, such as writing and speech; and a mask-like (expressionless) face due to rigidity. In the advanced stages, swallowing often becomes difficult and walking impossible as the patient becomes more and more rigid. Death is usually due to complications resulting from the symptoms, such as falls and infections.

Mike was talking at a meeting organised by the Parkinson’s Disease Society, explaining to journalists and press officers the necessity of medical research on animals. Various drugs, as well as operations such as deep brain stimulation, now provide enormous relief to sufferers of Parkinson’s disease, but all these interventions have to be tested on animals first before they can be used on people. Part of my job involved promoting medical research to the media, so I was there to learn how I could support the academics at my institution who did this kind of work in their dealings with journalists. At the time, animal rights activists were very active and intimidating; standing up and advocating research that had been tested on animals risked attracting their attention. But Mike had a powerful argument and as I sat listening to him talk about the operation that had transformed his life, I marvelled at all the research that had gone into developing the technique – it must have taken many decades. However, when the meeting ended I realised there was still one thing I wanted to know – why was it called Parkinson’s disease? Who was this man the world had forgotten? Who was this Mr Parkinson?

1

Living and bleeding in London

Ah! my poor dear child, the truth is, that in London it is always a sickly season. Nobody is healthy in London, nobody can be.

Jane Austen, 1816Emma

JAMES PARKINSON was born into the Enlightenment on Friday 11 April 1755. He grew up alongside the Industrial Revolution and died a Romantic on Tuesday 21 December, 1824. His life spanned a period of intellectual turbulence and political upheaval, burgeoning science and technology; they were dramatic and exciting times to be alive. Among his contemporaries were Mozart and Marie Antoinette, the chemists Joseph Priestley and Humphry Davy, the surgeon brothers John and William Hunter, Edward Jenner who discovered the smallpox vaccine, the poet William Wordsworth, the painter William Turner, and the geologist William Smith.1

James was the second of six children,* only three of whom – James and two younger sisters, Margaret and Mary – survived to adulthood; the three others died within their first five years.2

There is little known about his mother, besides the fact that she was called Mary and that burial records say she died on 6 April 1811 aged 90 – a grand age for someone of those times. Fortunately, because it was common in the eighteenth century for parents to choose names for their children that honoured their relatives – indeed, to avoid insulting anyone there was even a convention for the order in which the relatives were chosen – it becomes possible to identify that she was a Mary Sedgwick, baptised 16 April 1721 in Rotherhithe, Surrey.3 As people were generally buried less than a week after their death, it seems likely that Mary actually died a few days short of her 90th birthday.

Attempts to determine the birthdate and birthplace of Parkinson’s father, John, have met with less success.4 Furthermore, there is no record of any marriage between a John Parkinson and a Mary Sedgwick (or indeed any Mary at all) between 1750 and 1753 – the most likely period for a marriage to have taken place, given the arrival of the couple’s first child in November 1753.

Nor has any portrait of James Parkinson yet been found, although the internet boasts two different photos supposed to be of him. Unfortunately, since photography was not invented until 1838, fourteen years after Parkinson died, a photograph of him cannot possibly exist. The photographs in question are of two different James Parkinsons. One was a dentist who lived 1815–1895. The image of him was clipped from a group photo taken in 1872 of the membership of the British Dental Association. The man in the other photo, who has a big bushy beard, is a James Cumine Parkinson (1832–1887), an itinerant Irishmen who ended up as a lighthouse keeper off the coast of Tasmania.5

We are therefore left to imagine Parkinson’s physical appearance, and to help us do that we have a brief verbal description written by his young friend, Gideon Mantell.6 Mantell would have been in his early twenties when he knew Parkinson, then in his late fifties. He tells us: ‘Mr Parkinson was rather below middle stature, with an energetic intellect, and pleasing expression of countenance, and of mild and courteous manner; readily imparting information, either on his favourite science [fossils], or on professional subjects’.7 Like Parkinson, Mantell was a medical practitioner with a passion for fossils.

Another man with whom ‘our’ James Parkinson is often confused was an older James Parkinson (1730–1813) whose wife purchased the winning lottery ticket for the disposal of Sir Ashton Lever’s exotic natural history collection. Noted for the artefacts it contained from the voyages of Captain Cook, formation of the collection had bankrupted Lever. In order to recover some of the money he obtained an Act of Parliament which allowed him to sell the collection by lottery, but at a guinea each he only sold 8,000 tickets, when he had hoped to sell 36,000. The lucky James Parkinson who acquired the collection spent nearly two decades trying to make a success of Lever’s museum, eventually putting it up for auction in 1806.8 ‘Our’ James Parkinson was present at the auction and purchased a number of items.

The James Parkinson with whom this book is concerned lived all his life in Hoxton, a village located a mile north of Bishopsgate, one of the narrow medieval gates of the City of London,9 within the parish of St Leonard’s Shoreditch in the county of Middlesex. In a survey of 1735 the total number of houses in Hoxton was 503,10 but it was fast becoming urbanised as London rapidly expanded northwards during the Industrial Revolution. In 1700, London had a population of just under 600,000; a century later it had reached over a million and was the largest city in the world.11 Today Hoxton can be found on the enlarged maps which represent the very heart of London in its A–Z of streets. These pages cover an area of less than three miles across from north to south, and five miles east to west, which is larger than the whole of London was in 1750.

As the city became more and more prosperous during the eighteenth century this was reflected in Hoxton where the population grew rapidly. There was a phenomenal rise in trade in the docks and in business generally, which fed an increase in employment and attracted agricultural workers out of the fields and into the metropolis. Residential areas in the city were taken over for business purposes, and as houses were demolished to make room for factories, warehouses and offices, displaced residents and incomers were forced to find homes beyond the City walls in places like Hoxton. The City Fathers, wealthy merchants and businessmen who could afford a horse and carriage, were able to live where they chose and opted for country seats or sophisticated squares. ‘Oh how I long to be transported to the dear regions of Grosvenor Square!’ sighs Miss Sterling in George Colman’s popular comedy The Clandestine Marriage.12 Such Georgian squares launched a new style of town-house: the narrow-fronted terrace; and vertical living became both a novelty and a necessity as space became scarce and land more expensive. Terraces were often set around a square to compensate for the fact that the houses themselves had little land of their own.

The Parkinsons lived at No. 1 Hoxton Square, a three-storey terraced town house constructed between 1683 and 1720 around a large square of more than half an acre.13 The house was built of bricks since there was a requirement to use fire-resistant materials following the Great Fire of London. In almost every room there were large, open fireplaces carved in an elaborate design. Some of the rooms were connected by elegant arches and many had deep panelling on the walls with pastel colours painted on the ceilings. The most important rooms, impressively large, were on the first floor where long sash windows looked out over the square which formed the focus of this elegant community. But only the residents were able to enjoy its privileges, each householder owning a key to the garden’s delights. From these windows the Parkinsons could see the spire of St Leonard’s Church, a fine example of Georgian ecclesiastical architecture.14 There James was baptised on 29 April 1755, married on 17 May 1781, and buried on 29 December 1824. His grave can no longer be found in the graveyard; it is probably in the crypt along with hundreds of others that were moved there around the beginning of the twentieth century so that the road could be widened.15 However, a badly deteriorating plaque dedicated to the memory of his father, John Parkinson, can still be seen on the churchyard wall. John had been the much-loved apothecary surgeon in Hoxton for more than 40 years, fulfilling a position in society similar to that of today’s GP. The twelve-line inscription probably once told us who had erected the plaque and why, but it is now illegible. Another plaque inside the church, put up in 1955, celebrates the bicentenary of James Parkinson’s birth.

St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, as James Parkinson would have known it.

The original house at No. 1 Hoxton Square was still standing 100 years ago, although by then it was derelict.16 At that time it had a smaller two-storey building on the back with a central door that opened on to a side street. This door had probably been the entrance to the apothecary shop where the Parkinsons made up and dispensed medications. Behind that was yet another small building which may have been added at a later date to house Parkinson’s ever-growing collection of fossils. Side streets provided access to shops and services, but beyond these, when James was born in 1755, were open fields, market and flower gardens, orchards, and grand old mansions standing in extensive grounds.

Despite the apparent grandeur of Hoxton Square, sanitary conditions were appalling. Household waste fed into open ditches that flowed down the centre of the streets, since Hoxton had no sewer. The ditches discharged into a tributary of the Walbrook river that ran through Shoreditch; the Walbrook, now one of London’s several subterranean rivers, eventually released Hoxton’s waste into the heavily polluted Thames. At night there would be commodes in the bedrooms, while in most dining rooms there was a set of chamber pots hidden behind curtains or in a cupboard for the relief of gentlemen after dinner. These were generally emptied straight into the street, although one of the greatest causes of pollution of London’s waterways occurred with the introduction of the improved water-closet in the 1770s. Many of these overhung streams – the earliest and simplest way of disposing of the contents. The house itself probably had piped water, drawn from the Thames and supplied via pipes of elm wood laid under the main streets, although the source of that water was highly questionable and the contents virtually undrinkable, as one Scottish visitor lamented:

If I would drink water, I must quaff the mawkish contents of an open aqueduct, exposed to all manner of defilement; or swallow that which comes from the river Thames, impregnated with all the filth of London and Westminster – human excrement is the least offensive part.17

Rain water too, ‘being, from the soot and dirt on the roofs of houses etc, loaded with impurities’ was rarely used, except for the meanest domestic purposes.18

Originally the nine water companies in London were each allocated a different region of the City, but when ‘healthy competition’ was introduced, the result was cut-throat. Each company established separate reservoirs and pumping stations, tore up roads and pavements in order to lay competing sets of pipes, canvassed each other’s customers and made wild promises they had no hope of keeping, in order to steal a march on the competition. After a few years of this mayhem, the companies again agreed to divide the City between them and withdrew to their allocated districts, but then a cartel formed which allowed charges to rise steeply in order to pay for the costs recklessly incurred during the previous years of warfare. It’s a familiar story.

The primary sources of lighting were candles and oil lanterns, and the only source of heat was invariably an open fireplace burning coal in a cast iron basket, so not the least drawback to living in the City was the constant pall of thick smoke that hung around its shoulders. The travel writer Pierre-Jean Grosley complained that winter in London lasted eight months and that the smoke, ‘rolling in a thick, heavy atmosphere, forms a cloud which envelops London like a mantle’.19 The fallout from this cloud, soot, covered the buildings and anything left outside, even the horses. Aside from the burning of coal in the grates of every household in town, soot was generated by the thousand-and-one small businesses that choked the City’s back streets – the smithies, the potteries, the brewing, baking and boiling trades, and the myriad other enterprises. And the pall didn’t stay within the City walls: ‘the smoke of fossil coals forms an atmosphere, perceivable for many miles’, grumbled another tourist;20 so it can be assumed that even the Parkinsons’ fashionable residence, a mile outside the City walls, was covered in grime.

Several good schools existed in Hoxton and the surrounding area and James probably attended one of these, as his published advice on how to prepare young men for the medical profession refers to the need for them to have had a ‘common school education’.21 By the mid-eighteenth century the syllabus of many Middlesex schools included Latin, Greek and French, arithmetic, book-keeping, ‘all branches of the mathematics’, and the ‘use of globes’.22 Natural philosophy, the precursor to modern science, was introduced on to the curriculum of some private schools around this time, and since Parkinson considered natural philosophy an essential background for medical students, it seems likely he studied the subject at school. In addition to the languages already mentioned, he was able to read German and Italian, and he also used shorthand throughout his life, which he says he learnt as a boy. These were usually subjects for which extra fees had to be paid, suggesting his schooling was of a higher standard than a ‘common school education’.

Hoxton, renowned for its ‘dissenting’ ambience, offered university-level educational facilities in the form of the Nonconformist Hoxton Academy, which moved into Hoxton Square in 1764.23 Nonconformists advocated religious freedom and opposed State interference in religious matters, but as these beliefs did not ‘conform’ to the views of the established Anglican Church, nonconformists were restricted from many spheres of public life. They were also barred from various forms of education which compelled them to fund their own academies. The Hoxton Academy provided a university education for young men who were prevented from attending Oxford or Cambridge because of their dissenting views, its presence giving the Square an almost collegiate air. Although James is unlikely to have attended the Academy, since he and his family were members of the Anglican congregation at St Leonard’s, the Parkinsons undoubtedly knew many of its tutors, attending them and their students when they were sick. Among the Academy’s many well-known pupils was the radical political philosopher William Godwin who studied there for five years between 1773 and 1778.24 Godwin was just a year younger than Parkinson, so it is possible that they knew each other during this period. Whether or not this was the case, they both acquired a radical social conscience around this time that was to shape the rest of their lives, and they certainly knew each other later on.25

For most of Parkinson’s life ‘Mad’ King George III was on the throne. It was a reign dominated by wars: the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the American War of Independence (1775–1783), and the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802), which became the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815); each was almost twice the cost of the previous one and this hugely increased the national debt. Consequently, everything was heavily taxed, from hair powder to candles, and this burden fell heavily upon the working man. ‘More than two thirds of every shilling we earn, is torn from us by Taxes laid on the articles most necessary to the support of life,’ complained Parkinson.26 As a result, the population was frequently in turmoil, riotous and disordered. But such disturbances were a way of life in the eighteenth century – a distraction from the drabness of the life of the poor, a release of emotion and energy – and did little to disrupt the upper classes.

By 1760 London had begun to expand dramatically both north and south of the Thames. To accommodate these developments, London’s first bypass was built by two turnpike trusts. It bounded the north side of the metropolis from Paddington to the City, greatly diminishing the congestion caused by the innumerable herds of sheep and cattle wending their way along Oxford Street and Holborn to Smithfield Market. As the Industrial Revolution got under way and such major projects became commonplace, the open fields, gardens, orchards, and fine old houses for which Hoxton was noted fast disappeared.

At the same time, people flocked to cities from the fields at a rate that accommodation could not keep up with. With overcrowding and war came soaring rents. No longer could a family possess its own home but was obliged to share it with others until the little houses became grossly overcrowded. By 1801 the population of Shoreditch was 34,766, crowded into 5,732 houses; the parish later became the most densely populated square mile in the country. What had once been a nice middle-class area was fast becoming populated by the ‘lower orders’, such that by 1814 the inhabitants of Shoreditch were described as ‘Chiefly of the trading community: brewers, dyers, brick-makers, watch and clock-manufacturers, japanners etc, etc. The number of dissenters of all persuasions in this District is immense. The poor are exceedingly numerous.’27

There would have been little question that as the eldest son, James was to follow in his father’s professional footsteps. So at the age of sixteen, in 1771, he began seven years as an apprentice apothecary to his father, eventually taking over the practice when John died. In turn, James would teach his eldest son, John, who would take over the practice when James died, and John’s son James was to do the same when his turn came. Thus at least four generations of John and James Parkinsons worked as apothecary surgeons in Hoxton. It was a family business.

In the eighteenth century there were three types of medical practitioner: physicians, surgeons and apothecaries. Each was overseen by its parent body: the Royal College of Physicians, the Company of Surgeons (which in 1800 became the Royal College of Surgeons of London) and the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. There was a clearly defined hierarchy, with apothecaries at the bottom of the ladder and physicians at the top. Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians had to have a medical degree from either Oxford or Cambridge and comprised an elite group who supplied healthcare to the rich and were consulted in difficult cases. They were forbidden to practise a ‘trade’ such as that of apothecary, surgeon or man-midwife.

Below them came the physicians whose religious beliefs barred them from Oxford and Cambridge, and who therefore obtained medical degrees elsewhere. Their qualification licensed them to practise as physicians and to ‘dabble in trade’. Surgeons and apothecaries tended to pursue apprenticeships, but the latter remained largely unregulated until the Apothecaries Act of 1815. On completion of their apprenticeship, apothecaries could take an oral exam at the College of Surgeons that qualified them to practise as apothecary surgeons. Many did not – although they still practised surgery.

The apothecary’s original role had been to prepare and dispense remedies prescribed by a physician, in the same way that a chemist dispenses medications prescribed by a doctor today, but by Parkinson’s time the apothecary would prescribe for minor ailments himself. The majority of town apothecaries, and practically all those in the country, visited patients of the poor and lower middle-class, so would be admitted by the back door to attend the servants of the wealthy, while physicians, arriving in a chaise at the front door, administered to the family. The apothecary would prescribe and supply medicines he had compounded himself, the most common being clysters (enemas) which were recommended for symptoms of constipation and, with more questionable effectiveness, stomach aches and other illnesses.

Apprentice apothecaries were trained to recognise the many plants, berries, roots, barks and minerals used in various remedies, as well as in how to grind and mix the ingredients. On entering the apothecary’s shop, customers would have been enveloped in pungent smells, evocative of distant and exotic countries. Large jars of herbs, spices and medications lined the walls, and huge bunches of drying plants hung from the ceiling; drawers contained crushed oyster shells, mercury, dried roots, variously coloured powders, liquids and ointments that were all added to medications, as well as neatly arranged surgical instruments for bleeding and blistering patients or administering enemas; implements on display for compounding and dispensing drugs included a huge pestle and mortar, the apothecary’s most important piece of apparatus. Each apothecary had his own jealously guarded recipe book of medications, taken and adapted from published pharmacy books called pharmacopoeias.

When diagnosing a complaint, medical practitioners in the eighteenth century still adhered to the teachings of Hippocrates who, more than 2,000 years previously, had promoted the doctrine of the four ‘humours’ of the body: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile (or pus). Disease was defined as an imbalance of these humours; thus when an illness occurred it was the physician’s role to bring the body’s humours back into balance. Some 500 years after Hippocrates this method of treatment had been widely disseminated by Claudius Galenus, better known to us as Galen, a prominent Roman physician and philosopher of Greek origin, whose theories dominated and influenced Western medical science until well into the nineteenth century. He considered that blood was the dominant humour and the one most in need of being controlled, so he advocated frequent bloodletting, the popularity of which was reinforced after he discovered that veins and arteries were filled with blood, not air, as was commonly believed. In order to restore the balance of the humours, a physician would remove ‘excess’ blood from the patient or give them an emetic to induce vomiting, a diuretic to encourage urination, or a sudorific to bring on a sweat.

But the tide of knowledge was beginning to turn and in later years Parkinson recalled what a waste of time he felt his seven-year apprenticeship had been. He spent the first five making up medicines, an art he considered could have been obtained in as many months. In the remaining years he learnt bleeding, dressing a blister and, ‘for the completion of the climax – exhibiting an enema’,28 the colour and shape of the stool being an important part of diagnosis.

Bloodletting was considered an art. It was a procedure best left to the experienced practitioner, who would know how much to take and where to take it from. ‘In ascertaining the quantity of blood to be taken away,’ Parkinson explained, ‘not only must the sex, age, and strength, be considered; but also the degree of violence of the disease and the importance of the part affected.’ In cases where it was necessary to produce an effect on the whole body, blood could be taken from the most ‘convenient part’, but where a result was required in a specific area, ‘bleeding should be employed, as near as convenient to the inflammation’.29 Bleeding was to be done quickly so that the blood flowed as fast as possible, but one also had to take great care not to take too much for, as Parkinson admitted, there was a danger of ‘inducing other diseases, more difficult of removal, than the original complaint’. On the other hand, if too small a quantity was taken, ‘the disease will not be removed’. It was a fine line. Nevertheless, Parkinson advised that everyone should know how to open a vein and draw blood, just in case they had to do it in order to save someone’s life when no surgeon was available.30

After bloodletting, Parkinson considered that the most powerful method of ‘relieving the overloaded vessels and of lessening the disease’ was the proper administration of purgative medicines. Purging was a frequent and rapid evacuation of the bowels brought on by administering a purgative such as castor oil or the juice from the skin of an unripe cucumber, but again it was necessary to know exactly what effect this would have for fear of doing more damage than the disease itself. Some purgatives, for example, when used in conjunction with sudorifics to induce a sweat, could be counterproductive and stem the flow of perspiration, ‘and thereby occasion an increase of the original complaint’.

Blistering, or cupping, was believed to encourage the flow of blood and clear local ‘stagnation’. It was achieved by creating a vacuum in a heated glass cup placed flush against the patient’s skin; as the air cooled in the cup, a vacuum formed causing the skin to be sucked up into the cup. When sufficient pus was formed in the blister, it would be opened and the pus allowed to ooze out. Such blisters could be kept open for several weeks in order to obtain the maximum amount of pus. (In fact, by causing localised inflammation, cupping helps trigger an immune system response, so it is possible that in some cases patients did benefit from this treatment.)

Towards the end of his apprenticeship, in February 1776, Parkinson spent six months gaining practical experience at the London Hospital on Whitechapel Road.31 Depending on the fee paid, students either ‘walked’ the wards of a hospital, benefiting only by observing the surgeons in action, or, for a higher fee – around £50 a year – they became ‘dressers’. Parkinson became a dressing pupil to the surgeon Richard Grindall, which meant he helped with those patients directly under Grindall’s care, assisting the surgeon in dressing wounds, mending fractures, performing some of the lesser operations of surgery and, of course, bleeding patients when necessary. Each surgeon could be responsible for up to six dressers at any one time.

Grindall, who had been appointed to the surgical staff more than 20 years previously, was known for his operative skill and for his dedication to his profession. ‘He was also a great Oddity,’ recalled one student, ‘but a perfect Gentleman in his appearance and manner, never seen … but in a well-powdered wig, silk stockings and shoe buckles.’32 Often appearing in the wards late at night, Grindall would check on the progress of his patients who were critically ill. This attention to those in his care was unusual as surgeons did not stay on the premises and night visits were normally left to the hospital’s resident apothecary, or the dresser on duty.

Surgeons and physicians would work in the hospitals free of charge, earning an income by taking dressing pupils and apprentices, by giving lectures and by developing a private practice which they would often run alongside their hospital work. But establishing a practice could take many years, so it was necessary to first build up a good reputation in the hospital, since this would later attract the paying public to the practice.33 Connection with a great hospital was therefore extremely important. As a result, hospital posts were highly sought after and could be contested as fiercely and as expensively as seats in a parliamentary election. Unfortunately, in all the seven ‘great’ London hospitals at this time, there were only 22 posts for physicians and 23 for surgeons, so opportunities were few; an aspiring physician or surgeon had to wait until someone either resigned or died before a post became vacant.34 One such surgeon waiting in the wings at this time was William Blizard.35

After serving a surgical apprenticeship in Surrey, Blizard came to the London Hospital to study under the surgeon Henry Thompson, whom he eventually succeeded when Thompson died in 1780. While waiting for a position to arise, Blizard joined the London’s Board of Governors, a position he held at the time Parkinson was studying there. Although a man of extremely high standards who demanded a great deal from everyone around him, Blizard also had the ability to inspire; his one-time student John Abernethy recalled, ‘I cannot tell you how splendid and brilliant he made it appear’.36 Twelve years older than Parkinson, Blizard initially mentored the younger man, but as they came to realise they had similar political and religious views, and shared an interest in fossils, they developed a close friendship that would continue throughout their lives.

The sick and injured who flocked to the London Hospital came largely from the wharves of Rotherhithe and the workshops of Spitalfields, Aldgate, Wapping, Whitechapel and West Ham. Among the common medical ailments Parkinson helped Grindall treat were pneumonia, tuberculosis and infectious fevers. Many of the workers – women and children, as well as men – also suffered from scalds and burns, lacerations, fractures and crush injuries sustained during their work. Burns and scalds were common injuries in the home as well, with women in particular suffering terrible accidents when their highly combustible clothing caught fire. Should this happen, Parkinson advised first calling for help without opening the door – as the external air rushing in would immediately increase the progress of the flames – and then to ‘tear off that part of the clothing which is in flames’. If in a parlour, the burning woman was told to seize the water jug and pour it over herself. For this reason alone, the jug should be large and always kept full. If that did not put out the flames, she was to sit down on the floor, since standing was more likely to ‘render the communication of the flames to the upper part of her dress’, and smother the flames using the hearth carpet which, Parkinson recommended, should always form part of the furniture in every room, in case of such an emergency.37 The Parkinson establishment was undoubtedly a model household, equipped to cope with all such eventualities.

When Parkinson was studying at the London Hospital, apprentices, pupils and dressers were expected to attend lectures in various subjects likely to improve their medical knowledge. But although hospitals such as Guy’s and St Thomas’s had lecturers based there, the London, being on the edge of town, did not offer much in the way of these additional facilities. Only lectures on surgery and physic (the practice of medicine) were available, but if a student wanted to gain any semblance of a complete medical education, he would also need to take courses in anatomy, midwifery, medicine, natural philosophy and chemistry. All of these were on offer elsewhere in the City, but a student ‘must necessarily neglect part of his business at the hospital’, traipsing around London on foot in search of them.38

An artist’s impression of the new London Hospital, Whitechapel, in 1752.

It was entirely up to the student to choose which course to study and as each course charged a separate fee – around £3 to £4 – the less well-off might decide not to attend any at all. Furthermore, all dressers were required to be on hospital premises between 9am and 2pm, and again in the evenings between 6 and 9pm, so there was little time available for study. Years later Parkinson wrote angrily about the system for educating medical students, and what he considered to have been the ‘misdirection’ of his studies. Being placed behind the apothecary’s counter for seven years and receiving his hospital education in the manner described was ‘absurd’, making him feel he had been ‘robbed of his fair chance of becoming proficient in his profession’39 – for it was during his time at the London Hospital that Parkinson decided to become a surgeon.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, surgery had become a glamorous profession, many considering it had ‘arrived at such a degree of perfection in Great Britain as leaves no room for France any longer to boast of her supremacy. A journey to Paris is no longer necessary to complete a Surgeon’s education.’40 This success had been brought about by John Hunter, Henry Cline and others whose speed and skill with the knife had made them celebrities. The rich and famous flocked to be treated by them and many a young surgeon aspired to similar heights, despite having to ‘submit to long and heavy – and even wearisome plodding, through the paths of science’.41 As a young man Parkinson was no exception, although later in life he warned that celebrity could not be ‘cheaply purchased’, for the student had much to learn before achieving the ‘fame for which he pants’.42 As well as the study of natural philosophy, physiology, chemistry and physics, along with French and German in order to read ‘the numerous scientific works which are written in the French and German tongue’, an aspiring surgeon needed, above all, a good understanding of anatomy. It was the ‘key-stone’ to becoming truly proficient, and the only way to achieve the level of skill demonstrated by John Hunter was through the practice of dissecting dead bodies.

The Company of Surgeons was first established in 1745 and since that time criminals executed on the gallows had provided cadavers on which young men training to become surgeons could test their dissecting skills. A large number of eighteenth-century statutes specified death as the penalty for minor property offences and anyone stealing goods worth more than five shillings could be sentenced to hang.43 Execution was a public spectacle meant to act as a deterrent to crime and huge crowds would assemble to watch as the prisoners were transported through the streets. On arrival, they were stood in a horse-drawn cart, blindfolded and their hands tied together. The noose was then placed around their neck and the cart pulled away, leaving the condemned to hang until they died, which often took several minutes. Friends and relations might pull on their legs to help them out of their misery. After the execution, unseemly struggles for possession of the corpse often broke out between assistants to the surgeons who needed the body for teaching purposes and friends of the prisoner who wanted to give the victim a proper burial.

As demand among the surgeons had increased, the price of a cadaver had risen to over £100, and by 1750 grave robbing had become an alternative source of supply.44 But after the introduction of the Murder Act in 1752 it was no longer legal to give an executed murderer a proper burial, so instances of fighting over the corpses became less common. After that the bodies were taken straight to the Company of Surgeons for dissection and, as the surgeons received a regular supply of cadavers, the price fell dramatically. In the years immediately following the Murder Act, costs dropped as low as £3 8s, later stabilising at around £12 13s.

‘The body of a MURDERER exposed in the Theatre of the Surgeon’s Hall’, Newgate Calendar, 1794.

The Company of Surgeons had opened its newly built operating theatre, Surgeons’ Hall, in 1753, implementing a system of electing Masters, Wardens and Stewards of Anatomy to administer it. The Masters lectured in anatomy, the Wardens demonstrated dissection during lectures and made sure that everything was conducted ‘with Decency and Order’, and the Stewards dissected and prepared the bodies for the lecturer.45 Unfortunately, such was the unpopularity of these posts, which were ‘voluntary’ and considered a burden on people who were already extremely busy, that heavy fines had to be imposed on individuals not accepting their ‘election’. Even then many refused, preferring to pay the fines, which became an important source of income for the Company. But because of this difficulty in obtaining lecturers and wardens, over the ensuing 20 years the Company of Surgeons had become moribund and its reputation as a training establishment had declined. At the same time, several well-known surgeons had set up their own private schools of anatomy, considered by many to be more modern in their teaching methods and superior in their premises and facilities.

The year before James started training at the London Hospital, 1775, his father had been elected as Warden at Surgeons’ Hall, a position he had chosen to accept, rather than pay the fine, and which he held for two years. So when James began his training, he attended the anatomy lectures at Surgeons’ Hall, where he watched his father demonstrate the dissections. The cadaver would be cut up by the Steward before the lecture and only the parts to be discussed that day were taken into the theatre, since a whole cadaver would rapidly decay due to the body heat emanating from the students. The Warden, having demonstrated the elements they were to observe, would then pass round each body-part, instructing students to examine it in detail before handing it on.46 Meanwhile, the Master would explain its purpose, drawing important elements on the blackboard in order to illustrate how the parts interacted with each other. Parkinson, ever critical of prevailing teaching practices, considered this an inappropriate way in which to demonstrate anatomy. He argued that chopping up the body beforehand and presenting it to the student in many separate pieces over a long period of time made it difficult for them to acquire an overview of the whole ‘human fabric’ and to understand how all the parts were related to each other.47 Perhaps because of such criticisms, later that year a committee was set up to review the Company’s method of training students. As a result, the two unpaid Master of Anatomy positions were abolished, their place being taken by a Professor of Anatomy on a salary of £120 a year.

Parkinson evidently studied hard, doing the best he could in difficult circumstances, but being a student in the big city seems to have changed little over the past 200 years, and however diligent he tried to be, ‘public spectacles, feasts, balls and assemblies daily hold out their temptations; and pleasure, under every fascinating form, will seek to secure you in her snares’. Friends were a distraction too: ‘Your friend invites you to accompany him to the play but you, knowing that you have some evening lecture to attend, beg to be excused. Your objection is opposed by the observation “you really make too much of a slave of yourself – you must have some little amusement” and so you are enticed to go out.’ Having given way to such inducements, the evening cannot be concluded ‘without a bit of supper and a glass of wine. The glass circulates freely, until the conviviality of the evening renders your attendance at any lectures impossible.’ Next morning, ‘Your head aches and your spirits are low, you therefore trust to a friend for his notes of the evening lecture, but these are not so intelligible as your own. Thus three or four lectures are lost to you.’48 Generally, though, Parkinson was a model pupil almost desperate to take advantage of his time at the London. Even so, having only six months in which to complete his studies meant he finished his training as a dresser still feeling ‘miserably ignorant’.

Footnote

* See the Parkinson family tree on page vi for dates of James Parkinson’s siblings and other members of the family.

2

The hanged man

It is with the utmost satisfaction I can inform you of a case in which I have been able to restore to life one, who before the institution of your Society, would probably have been numbered with the dead.

John Parkinson, 1777Transactions of the Royal Humane Society

AT SEVEN O’CLOCK in the evening, on Tuesday 28 October 1777, there was a loud rap at the door of No. 1 Hoxton Square. John Parkinson was urgently summoned to the house of Bryan Maxey who, as the messenger informed him, had hanged himself. John called for James to accompany him and they immediately set out for Maxey’s house about a quarter of a mile away. There they found Maxey who had apparently been dead for half an hour: a coldness had already spread over his body and his jaw had become so fixed that they had to use considerable force to move it. A woman in the house, aware that a reward was offered by the Humane Society to those who resuscitated the dead, had tried with some small success to keep Maxey warm by rubbing his stomach with a flannel. In addition, a neighbour who practised bleeding had taken about eight ounces of blood from Maxey’s arm before the Parkinsons arrived.

Father and son immediately began to give Maxey mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, a new and controversial technique introduced by the Humane Society just a few years previously. James, now 22 and in the final year of his apprenticeship, performed most of the physically taxing work, since John was in poor health. Eventually, as John reported to the Humane Society a few days later, they were successful in returning Maxey to consciousness. After 40 minutes of resuscitation he had given a deep sigh which was followed by an increase in the strength of his pulse. After an hour he was able to breathe without assistance and in another half an hour he regained consciousness. ‘He then complained of an excessive pain in the head,’ explained John, but once given some warm brandy and water, followed by a ‘purging’ broth which enabled him to produce a stool, Maxey was deemed well enough for the Parkinsons to leave.1 Producing a stool was, of course, a vital sign of life.

By the end of a week, Bryan Maxey was completely recovered except for a slight dimness of vision and a feeling of numbness on the right side of his head. He expressed the utmost sorrow for his ‘crime’, as suicide then was, and gratitude to those who were instrumental in restoring him to his wife and children. This satisfactory result was honoured by the Humane Society with the award of its Silver Medal to the young James Parkinson who had worked hard to restore Maxey to life. It became one of his most treasured possessions and he proudly left it to his eldest son in his will.

We are not told why Maxey tried to kill himself, but he appears not to have been alone in the quest to find an end to his misery. According to the Reverend Caleb Fleming,2 a dissenting minister and neighbour of the Parkinsons, there was an epidemic of ‘self murder’ around this time – a period of political and financial instability caused by the American War of Independence.3 As the Reverend Fleming explained, the war had resulted in ‘an alarming shake to public credit’, as well as an ‘obstruction to trade and commerce’ which in turn caused widespread unemployment. The price of food rose sharply and while the rich indulged themselves ‘in every debauchery and extravagance’ imaginable, the poor starved. Unable to cope, many committed suicide: ‘The insolvent and dissatisfied are cruelly laying violent hands on themselves in great numbers,’ lamented Fleming.4

Had Maxey died, the punishment for his crime would have been the forfeiture of all his goods and chattels, as well as those belonging to his wife. So the family would have lost not only a husband and father, but all its worldly goods as well. Even the Reverend Fleming, who considered the heinous crime of self-murder to be an act of High Treason against the sovereignty of the Lord, felt that punishing those left behind was too severe. Instead, he proposed ‘the naked body [of the suicide] should be exposed in some public place’, over which the coroner would deliver an oration on his terrible crime. The body, like that of the murderer, should then be given to the surgeons who would use the parts to demonstrate anatomy to their students. Such a dreadful punishment would have terrified the likes of Maxey, since the idea of dissection after death contravened a belief in the sanctity of the grave where the dead body was supposed to rest undisturbed until Judgement Day when it would be reunited with the soul. If the body was dissected, it would never find its soul, which would wander around in Purgatory forever. Maxey was grateful Parkinson saved him from this fate worse than death.

The Humane Society had been founded just three years earlier by two doctors who were concerned by the number of people wrongly taken for dead and subsequently buried, or dissected, while still alive. The Newgate Calendar, a popular book that reported the crimes, trials and punishments of notorious criminals, quoted the words of a surgeon about to dissect a murderer recently taken down from the gallows:

I am pretty certain, gentlemen, from the warmth of the subject and the flexibility of the limbs, that by a proper degree of attention and care the vital heat would return, and life in consequence take place. But when it is considered what a rascal we should again have among us, that he was hanged for so cruel a murder, and that, should we restore him to life, he would probably kill somebody else. I say, gentlemen, all these things considered, it is my opinion that we had better proceed in the dissection.5

The Humane Society advocated artificial respiration and recommended warming the body, administering stimulants, and bleeding, provided the latter was done with caution. For some years, blowing tobacco smoke into the rectum (fumigation) was also considered beneficial, bellows being used ‘so as to defend the mouth of the assistant’.6 The Society stressed the importance of prompt and prolonged treatment – no case should be abandoned unless vigorous efforts, maintained for at least two hours, had been unsuccessful. Parkinson, however, recommended attempting resuscitation for no less than three or four hours, disdainfully considering it ‘an absurd and vulgar opinion, to suppose persons irrecoverable, because life does not soon make its appearance’.7

Keen to promote these new resuscitation techniques, the Humane Society initially offered money to those rescuing someone from the brink of death. A handsome reward of two guineas was distributed among the first four people to attempt the rescue, and four guineas paid if the person survived. But a scam soon became widespread among the down-and-outs of London: one would pretend to be dead while the other brought him back to life, and they would then share the reward money between them. Consequently, monetary rewards were soon replaced by medals and certificates.

A network of ‘receiving houses’ was set up in and around the Westminster area of London where bedraggled bodies, most of them pulled out of London’s waterways, could be taken for treatment.8