10,55 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

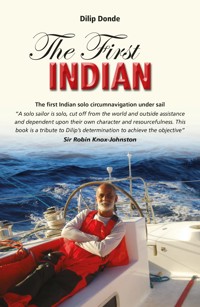

An engrossing narrative of one man's struggle to achieve his dream against all odds, this is both a fast-paced adventure and a telling commentary on how heroes are often made despite the system they operate in, by dint of sheer perseverance and commitment to a chosen path. Above all, it's a paean to the power of self-belief that serves to inspire, motivate and exhilarate. On 19 May 2010, as he sailed INSV Mhadei into Mumbai harbour, Commander Dilip Donde earned his place in India's maritime history by becoming the first Indian to complete a solo circumnavigation under sail, south of the 3 Great Capes. The feat, successfully completed by just over 200 people in the world, had never been attempted in his country before. In his own words, the book chronicles his progress over four years, from building a suitable boat with an Indian boat-builder; weaving his way through the 'sea-blind' and often quixotic bureaucracy; and training himself with no precedent or knowledge base in the country, to finally sailing solo around the world. During this gruelling task he was mentored by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, the first man to sail solo non-stop around the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

.

The real lives of sporting heroes on, in & under the water

Also in this series...

Golden Lilyby Lijia Xu

The fascinating autobiography from Asia’s first dinghy sailing gold medallist

more to follow

Published in 2016 by Fernhurst Books Limited 62 Brandon Parade, Holly Walk, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 4JE, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1926 337488 | www.fernhurstbooks.com

Copyright © 2016 Dilip Donde

Dilip Donde has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Published in India in 2014 by Maritime History Society

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a license issued by The Copyright LicensingAgenev Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-909911-49-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-909911-83-3 (eBook), ISBN 978-1-909911-84-0 (eBook)

Photography All photographs supplied by Dilip Donde

Designed by Rachel Atkins

.

Contents

Foreword

7

Preface

9

Acknowledgements

13

Chapter 1

A Path Less Travelled

17

Chapter 2

An Invaluable Apprenticeship

25

Chapter 3

A Suitable Boat

34

Chapter 4

Apprenticeship Again

37

Chapter 5

Finding a Boatyard

41

Chapter 6

Training on Old Sameer

44

Chapter 7

Humour in Uniform

50

Chapter 8

Training Boat

60

Chapter 9

The Eldemer Episode

63

Chapter 10

Training Sortie That Wasn’t

67

Chapter 11

A Womb for the Boat

76

Chapter 12

Finally, Some Sailing

83

Chapter 13

Robin’s First Visit

86

Chapter 14

The First Hurdle

88

Chapter 15

Our Boat Building Guru

91

Chapter 16

Adieu Sameer

94

Chapter 17

Mhadei

97

Chapter 18

Mhadei’s Baby Steps

115

Chapter 19

Colombo Calling

121

Chapter 20

The Mauritius Adventure

127

Chapter 21

Charting My Course

141

Chapter 22

The Final Checklist

145

Chapter 23

Down Under

155

Chapter 24

First Taste of the Southern Ocean

193

Chapter 25

A Little Town with a Large Heart

218

Chapter 26

The Everest of Ocean Sailing

227

Chapter 27

Hop Across the Atlantic

248

Chapter 28

Home Run

263

Epilogue

278

Glossary

280

.

Foreword

by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston

The Indian sub-continent has a seafaring heritage that goes back at least five millennia. Its long seaboard provided a cradle for seamen that still exists today. In my own time with the British India Steam Navigation Company, we relied on this plentiful source of people accustomed to the sea to provide the seamen for our vessels.

Since Independence in 1947, the Indian Merchant Navy and the Indian Navy have expanded hugely, but yachting has remained the sport of a few. One organisation that has appreciated the value of boat handling skills, and the effect of wind and tide on a vessel, is the Indian Navy. So it was not a total surprise when I received a message from Retired Vice Admiral Manohar Awati, asking for advice on how he could send a young officer around the world solo as an encouragement to the sport, and also to put India on the solo circumnavigating map. Both seemed excellent objectives and I responded quickly.

I had served with Indian crews for nearly 14 years during my time at sea. India had been my home for five years, living in Bombay, now Mumbai, and it was where I built my 32 foot Bermudian KetchSuhailiwhich became the first boat to ever circumnavigate the world non stop and solo. So I had a knowledge and love of India and its people.

At the time I was preparing my 60 footer to participate in the Velux 5 Oceans solo around the world race and felt that if the young officer joined me for the preparation period, he would pick up an awareness of what was involved in taking a boat into the watery Himalayas of the Southern Ocean for a month or more, and that is how I came to meet with Dilip.

The rest of the story is about Dilip Donde. A solo sailor is solo, cut off from the world and outside assistance and dependent upon their own character and resourcefulness. This book is a tribute to Dilip’s determination to achieve the objective and become the first Indian to ever sail solo around the planet.

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, 2016

.

Preface

He who would go to sea for pleasure, would go to hell for a pastime.

- Old French Proverb

On 27 Apr 2006, I volunteered for what then appeared to be an absolutely crazy project. ‘Project Sagar Parikrama’, as it would soon be christened, involved building a sailboat in India and then undertaking a solo circumnavigation of the earth in the boat. I volunteered for the project without really thinking and with absolutely no idea of what I was getting myself into. Till then I did not know that people sailed solo in big yachts nor had I ever set foot on a large yacht. I had been a recreational sailor since joining the Navy, content with sailing dinghies on weekends and enjoying my time outdoors whenever I could. I did do a short tenure on the Navy’s sail training ship INSTaranginias the first mate but there, with a crew of over 70, solo sailing was the last thing on my mind! I wasn’t alone in my ignorance; it was shared by over a billion Indians. In a way, by volunteering for the project without a second thought, I had thrown myself in the deep end of the pool without bothering to enquire about swimming lessons.

I did manage to keep my head above the water eventually and that is what this book is about. Some 170 people had already completed a solo circumnavigation before I volunteered for the project. So in a way, I was treading a somewhat beaten path. The crucial difference was that I was trying to do it in India, with an almost total ignorance of the subject, an inherent inertia against anything new and an intransigent and quixotic bureaucracy.

When I finished my voyage, most people I talked to wanted to hear about the experiences I had at sea, not realising that the hard work put in for over three years, before starting, was responsible for my safe return. The story of Sagar Parikrama would be incomplete without talking about those three years. For me they were as exciting as, and often more unpredictable than, sailing the Southern Ocean. When I look back at my journey from volunteering for the project to finishing the circumnavigation, I realise that there were a number of plots and subplots in the story with me being the only constant. This book, thus, is an attempt to tell the whole story as I lived through it.

The challenge of Project Sagar Parikrama when looked at in its entirety was not just about building a boat and sailing her solo around the world. The single biggest hurdle was neither the boatbuilding nor sailing solo through the Southern Ocean. It was to keep believing in myself that the project would happen notwithstanding the odds stacked against it. I was not the first person who was given the opportunity to do the project by the Navy. But I was definitely the first to grab it. Had I not done so, I am sure someone else would have. But then every time I looked at myself in the mirror, for the rest of my life, I would have thought, “I had the opportunity and I could have done it, but I didn’t!” What a horrible feeling that would have been! Not having to live with something like that is perhaps the biggest reward I got from the project – it was well worth the effort and risks.

In India, a government project that meets all deadlines, exceeds its aims, manages to stay under budget while leaving a proud legacy and a million dollars worth of hardware for future generations would be an anomaly – but that is exactly what has been achieved by this project. It is thus an Indian success story in more ways than one.

Commander Dilip Donde

.

Acknowledgements

While a single person undertakes a solo unassisted circumnavigation, the project cannot be completed without the wholehearted support of a number of people who contribute in its planning, preparation and execution. Without them, the sailor would not be able to go to sea in the first place. The success of the project, thus, is the success of the team with the solo sailor being the representative to receive the kudos on their behalf. It is thus important to acknowledge the contribution of the team members; some of whom were actively involved with the project at various stages while others helped without being directly involved.

Solo circumnavigations in modern boats are expensive affairs. Inevitably, the first and the biggest hurdle is to get the necessary funds. In my case, this hurdle was easy to surmount thanks to the generous funding provided by the Indian Navy and, by implication, the Indian taxpayer. While making sure the necessary funds were made available, the Navy gave me a free hand to use them as I deemed fit. This is all the more remarkable considering my lack of experience and the odds stacked against the project at every stage.

The Navy and the Indian taxpayer are faceless entities made up of well meaning people but there are many I can name who went out of their way to make this project happen. In a project lasting almost four years, the list can go on for a couple of pages. I will thus try to prune the list by naming a few and asking the others to excuse me for not including their names – this does not reduce my gratitude towards them in any way.

First and foremost, I must thank the mentor of the project, VAdm Manohar Awati (Retd), for conceiving the idea of a solo circumnavigation by an Indian in an Indian built boat. It was a big idea that only someone like him could have conceived and pursued so relentlessly. Thanks also to Adm Arun Prakash (Retd), then Chief of Naval Staff, for accepting the idea and handpicking me for the task, Adm Sureesh Mehta (Retd), his successor, for keeping up the momentum, VAdm Sunil Damle (Retd), VAdm Shekhar Sinha (Retd), RAdm N K Misra (Retd), Cmde R S Dhankhar, Cmde Sukhdev Virk (Retd), Capt Subir Sengupta, their successors and officers from Naval Headquarters who steered the project; Capt S J Contractor (Retd) for selecting the boat design and getting us in touch with Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, the first person to sail solo and non-stop around the world; and Sir Robin Knox- Johnston for putting us on the right track and mentoring me. In fact, in 2006, when everyone at home doubted me, he confidently ordered the first copy of the book that I would write on completion of my solo circumnavigation. And three years after completion of the project, when I was still struggling with the book, he put me in ‘voluntary solitary confinement’ at his lovely house in the UK to ensure that I completed the book you are about to read!

I am quite convinced that anyone can do a circumnavigation in a well-built boat while the best of sailors would falter in a badly built one. My debt of gratitude, therefore, is to the boat-builder Mr Ratnakar Dandekar and his team at Aquarius Fibreglas Pvt Ltd, Goa. It was as much a pioneering project for them as it was for me and they exceeded all expectations while standing up to the challenge. Ratnakar is the face of his company but he had a large team with him, all of whom put in their best to produce the fine boatMhadeiis. Some of them may read this book while many others will not get the opportunity to; nevertheless, my gratitude towards them remains the same.

I thank Mr Johan Vels from the Netherlands for teaching us the nuances of building a boat likeMhadei,Mr Alan Koh of International Paints for showing us how to make the boat pretty, boat designer Van de Stadt Design Bureau and all the equipment suppliers for providing us a good design and equipment that could withstand the Southern Ocean as well as our inexperience, and Mr Nigel Rowe for suggesting we install a wind vane steering, which perhaps saved my life in the Pacific.

While successful completion of such a voyage is important, it is equally important for the story to reach a wide readership to enable them to be a part of the adventure. The blog I wrote from sea achieved this to a large extent. This was thanks to the efforts of my close friend Cdr Anshuman Chatterjee, who designed my blog, and Mr Mandar Karmarkar who regularly plotted my positions while I was at sea and eventually prepared a track chart of the entire voyage. Many of the photographs in the book and those in my blog were clicked from the excellent camera I received days before departure thanks to the efforts of Cmde Amar Mahadevan.

Many thanks to my one-man shore support crew and training partner Cdr Abhilash Tomy who joined me a few months before departure and became indispensable. I couldn’t have asked for anyone better! A special thanks to my mother and the rest of the family for getting totally involved with the project, never showing their apprehensions, and lending a helping hand whenever required.

Finally, I express my gratitude to the Maritime History Society and its Curator, Cdr Mohan Narayan (Retd), for readily offering to publish this book in India, Mrs Arati Rajan Menon for editing the draft, pro bono, and the team of Manu and Madhuri Naik for designing and printing the Indian edition. I am delighted that this international edition is being published by Fernhurst Books, UK – I am grateful to Jeremy Atkins for offering to publish this.

Commander Dilip Donde

.

Chapter 1

A Path Less Travelled

“Dilip, are you in some sort of trouble with the Navy?” asked my mother one evening as we finished dinner at home in Port Blair. I had pushed away the empty dinner plate absentmindedly and was back to working on my laptop.

“What makes you think so?” I asked, trying to sound as nonchalant as possible while my brain was busy trying to word a suitable reply. The moment I had been apprehensive about for the past two months seemed to have arrived.

“Why have you suddenly started getting so many calls from Naval Headquarters, including the office of the Naval Chief? I think it is all very unusual so will you please tell me?” She had been staying with me for the past nine years and must have noticed the change in my routine since I got back from a sailing trip to Mumbai two months back. Through the years I had made it a point never to take any work home, howsoever busy the schedule. Since my return, however, I had been sitting almost every evening with a laptop borrowed from the office, reading up and writing well past midnight.

“I won’t call it trouble but, yes, there is something I got myself into when I visited Mumbai for the sailing trip. I didn’t tell you earlier as the whole thing still appears a bit harebrained and unrealistic to me,” I mumbled, trying to find the right words to break the news and minimise any possible resistance.

“You can tell me whatever it is,” persisted my mother.

“The Navy has been looking for someone to undertake a solo circumnavigation in a sailboat and I volunteered, though I am not exactly sure what it involves.” I decided to play it straight, acutely aware of my terrible diplomatic skills, and waited for her reaction. The reaction was surprisingly positive, though not too unexpected. “That is very good. Give it your best shot, opportunities like this don’t come every day, but remember it is a one-way street!” she responded after a pause. “Don’t ever think of backing out.”

I decided to test her further by telling her that there was a good possibility that I may not come back alive from the trip. No Indian had undertaken such a trip, less than 200 in the world had been successful, and no one kept count of the unsuccessful attempts. That didn’t deter her much as she calmly replied that I had to go some day like everyone else and it would be far better if I went trying to do something worthwhile! All she asked, in return of her full support, was to be able to read up as much as she could on the subject.

With her full support assured, I decided to fill her in on the events so far...

On 27 Apr 2006, before the start of the Mumbai to Kochi J 24 sailing rally that I was participating in, I met Capt Dhankhar, the Navy’s Principal Director of Sports and Adventure Activities. Since he had flown down to flag off the rally along with the Chief of the Naval Staff, or CNS, the conversation was about ocean sailing in the Navy. As I escorted him to the Sailing Club moorings, he almost casually mentioned that the Navy was toying with the idea of sponsoring a solo circumnavigation by a naval officer.

“Can I be a part of it in some way?” I blurted out, stopping him in midsentence, throwing naval protocol to the winds. I just couldn’t help it, the whole idea sounded so exciting though I had no clue what exactly was involved.

“Would you like to take it on? Should I tell the CNS that you have volunteered or do you need a little time to think about it?” he asked in his characteristic measured tone, with a hint of scepticism.

“Yes sir, please do tell the CNS that I want to volunteer, I don’t need any time to think!” I replied, my brain in overdrive. Less than a minute back I was ready to play any part, howsoever small, in this unknown project because it sounded interesting and suddenly the entire project seemed to be falling in my lap. I didn’t bother to ask what exactly the Navy had in mind, all my fuzzy brain could sense was that this was something exciting and I shouldn’t let go of the opportunity.

“Okay, now that you have volunteered, can you make a project report and send it to me by next month?”

In less than five minutes of what seemed like casual talk, I had gotten myself into the biggest soup in my life with a very vague idea about what exactly it was!

The Captain had been my instructor during my Clearance Diving course and had observed me closely during those stressful days. That, along with my declared enthusiasm for ocean sailing and my past experience as the Executive Officer of INS Tarangini during her first round the world voyage in 2002-2003, probably prompted him to check if I was interested in this project. Apparently I wasn’t the first person he had asked but was definitely the first to fall for the idea, thus ending his search.

Later in the day, the CNS, Adm Arun Prakash, flagged off the rally. In his speech he declared that the Navy was ready to sponsor a solo circumnavigation under sail provided someone volunteered to take on the challenge. As we lined up for a group photograph, he approached and said, “Dilip, I heard you have volunteered!” I just nodded my head and murmured, “Yes sir. Let us see.”

“So that is the story so far. Now I am required to make a detailed project report and send it to Naval Headquarters as of last month, which explains the frequent calls from Delhi. Honestly, I don’t have a clue about the subject and have been trying to read about it on the Internet, which seems to be the only source of information here.” I promised my mother that I would pass on whatever I read on the subject to her and got back to finalising my report. Her unstinting support was a burden off my head. I didn’t realise it then, but I had just conscripted the first member of the team for ‘Sagar Parikrama’, as the project would be called.

More than a month went by and I still hadn’t submitted my project report. One reason was a fairly busy work schedule that allowed me to read up on the subject only after dinner at home; the other, a total lack of knowledge about the subject. It would be an understatement to say that I was groping in the dark. The more I started reading, the more I started realising that this was not something romantic and poetic as I had initially thought but would involve a lot of hard work and would be far more difficult than what I had imagined. Surprisingly, though, that increased my excitement and determination to make it happen.

By Jul 2006, I managed to submit my project report to Naval Headquarters (NHQ) and decided that if I had to do a circumnavigation it had to be a proper circumnavigation under sail, going through the Southern Ocean, round the three Great Capes, Cape Leeuwin, Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope. I could have proposed following the route taken by the previous Indian sailing expeditions inTrishna, Samudraand INSTaranginithrough the Suez and Panama canals, called it a circumnavigation and no one would have been wiser, in the country at least! In fact, on hindsight, things would have turned out to be much simpler as I could always have pointed at ‘precedence’, something that opens many a door when dealing with the bureaucracy. I could have had a whale of a time stopping at 40 to 50 ports over a period of a year or two with a smooth sail through the Trade Winds! But then that wouldn’t have been the real thing. Even if the Navy, and the taxpayer who was essentially funding my trip, didn’t realise it, I would, and it just would not be right!

A month went by after I submitted the report. I was still clueless about what exactly to do. While I continued reading on the subject and sending the odd email enquiring about suitable second-hand boats, the whole idea had started getting a bit fuzzy and unrealistic as I got caught up in day-to-day activities.

For probably the first time ever, I had planned a nice holiday in Aug 2006; I had invited a close friend to the Andamans to explore the islands, booked my tickets to go to the mainland after that, handed over my duties at work in time and was all set to have a good time! My friend arrived as planned – and so did the calls from NHQ and a certain Vice Admiral Manohar Awati (Retd)! I was told that I was to go and work with Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, who apparently was the first person to have sailed solo and non-stop around the world. I had no idea who he was or what his achievements were. I did download information about him from the Internet but didn’t get much time to read with a house full of guests. All I knew was that he was trying to get ready to take part in a solo round-the-world race called the Velux 5 Oceans Race and had resigned from the chairmanship of his company as the company was conducting the race. When asked for his advice on my project, his response had been simple and characteristic: “Send him to work with me and he will know all there is to learn!”

The frequency of calls and the things I was supposed to do ‘as of yesterday’ increased so much that I was sitting in my office almost as much as on any working day. I finally got myself recalled from leave, little realising that that was the last, albeit short, holiday I would get for the next five years!

I left the Andamans before my friend – still at my home and now exploring the islands alone – and headed for the mainland. I was to go and meet the ever enthusiastic Vice Admiral Awati before heading for Delhi to complete my deputation formalities. The 80-year-old admiral had been egging on the Navy for years to undertake a solo circumnavigation. He lives with his wife in a remote village called Vinchurni, about 320 km from Mumbai, which with a population of 500 is small even by Indian standards! I landed in Mumbai, borrowed a friend’s car and went searching for the village few had heard of, finally making it by afternoon. I had interacted with the Admiral in passing some 10 years ago and he obviously didn’t remember me. We talked about the project, which wasn’t much really as it was more of an idea at that stage. He and his gracious wife made me feel at home instantly and when they insisted I spend the night with them instead of heading back to Mumbai and driving past midnight, I agreed without much fuss. As I was to stay for the night, I went for a nice long walk with the Admiral in the evening and had a sundowner with his wife while he retired to bed at 1900 h. The conversation was both interesting and varied. I enjoyed their company and left for Mumbai early the next morning. Much later and I am not sure how, I started getting a feeling that I had been under some sort of a probation and under observation during my stay! Two years into the project, when I had developed a good rapport with him, I finally asked him if what I suspected was true. He very calmly told me that I was indeed under observation and that after I had gone to bed he woke up and discussed me with his wife! While he had formed a favourable opinion about me, he wanted to take a second opinion from his better half as he relies on her gut feeling more than his own. Apparently, she told him that I seemed alright and should be able to take on the project!

“What if either of you had thought that I was not the right person for the job?” I asked.

“I would have asked the Navy to send me another guy!”

The next day, I drove up to Mumbai and met Capt Soli Contractor (Retd), then Commodore of the Royal Bombay Yacht Club. He had represented India at the Munich Olympics in 1972 and was to be the technical advisor for the project. While talking to him, I realised that not only was I to be the first Indian to undertake this project but that the trip was to be undertaken in an Indian built boat. Never mind that India has virtually no yacht building industry to speak of! The whole idea was sounding crazier by the day and thus more exciting.

The next stop on what was fast becoming a voyage of discovery was Delhi. I was quite unfamiliar with the city in general and NHQ in particular, having steered clear of any appointment there so far. It was a whirlwind visit getting the paperwork ready for my deputation and for the project that was to follow. The Chief of the Naval Staff wanted to meet me before I left.

The first question he asked me, in humour and with a smile on his face, when I walked into his office was, “Dilip, have you gone completely mad?” I grinned, “Looks like that, Sir!” I had served on his staff 11 years back when he was commanding the Eastern Fleet and he knew me well. He wanted to know if I was under any sort of pressure and understood what I was getting into. Once he was satisfied, we got talking about the project. He was retiring within a month and promised to get the ‘Approval in Principle’ from the Defence Minister before retiring. He also insisted that I draft out a letter giving an outline of the project, addressed to all the naval formations. I was a little sceptical; we knew what we wanted to achieve but had no firm idea as to how we were planning to achieve it. When I naively pointed this out to him, he explained that he wanted the project to happen and the best way to ensure that it did not get scuttled after he retired was to leave his successors no option! He had already thought of an appropriate name for the project, ‘Sagar Parikrama’, literally meaning circumnavigation of the oceans in Hindi. No other name could have summed up the nature of the project so well and in simpler words.

While doing the rounds of NHQ and within an hour of the government approving my deputation to go and work with Sir Robin, I landed up at the personnel directorate. The ‘Sea Board’ for my course to decide the list of eligible officers to go to sea had been held the previous day. Not making it in the Board means the end of your career as you have virtually no chance of making it to the next rank. I bumped into an old friend who worked there. “I have made it in the Board, but unfortunately you haven’t,” he informed me, pulling a long face. “Cheer up mate, I’m quite glad!” was my reply. “Now I can concentrate on my project full time!”

.

Chapter 2

An Invaluable Apprenticeship

Once my paperwork was done, I began writing to Sir Robin asking him if he wanted anything from India, what sort of clothing to carry, his exact location, what I was to do once I got there, and so on.

There were so many questions and with no one to answer them at home, I kept shooting out mails as and when something popped up in my head. After a while, I started feeling a bit sheepish and started one of my mails with, “Here is another silly question...” His reply was prompt and something I will remember all my life. “There is nothing like a silly question! A question is a question and I would rather have you ask as many of them as you want rather than come here and be lost at sea!” I have followed his advice ever since and in a project where we were trying to learn everything from scratch, it was valuable advice indeed. When he asked me to get an audio CD of the 1960s Bollywood epicMughal-e-Azamfor him I was mighty amused. A few days later when I got to know him better, I realised the reason.

I landed in London and was received by the assistant to the Indian Naval Advisor who promptly transported me to Waterloo station and despatched me to Portsmouth by the next available train. Once in Portsmouth, I called up Sir Robin who asked me to come over to Gosport, a short ferry ride away. I was to call him once I reached Gosport and we were to go to an Indian restaurant for dinner with some friends. I reached Gosport alright, only to discover that I had left Sir Robin’s telephone number at my hotel in Portsmouth. I tried looking for him for a while, which wasn’t easy as we had never met before. I gave up after a while and headed back to Portsmouth feeling like a real idiot. What a wonderful way to start an apprenticeship!

The next morning, I reached Gosport and called up Sir Robin. He appeared within minutes and took me to the boatyard right next to the ferry point. I had never met a knight before and naturally addressed him as ‘Sir’. He sorted that out within the first two minutes by telling me to drop the ‘Sir’ and address him as Robin. He had an overall ready for me, and told me that his ulterior motive in allowing me to come and work with him was to brush up his Hindustani which he had picked up while working with the British India Steam Navigation Company in the 1960s.

Thus began my most valuable apprenticeship. The first task was to sand the boat’s boom and get it ready for painting, something that I had never done in my life. Robin’s boat,Grey Power,a carbon fibre ‘Open 60’, had been entirely stripped down and was being reassembled to get her ready for the race. The pace of work over the next three weeks was hectic. I would reach the boatyard by ferry around 0830 h everyday and start doing whatever work came my way. Robin would always be around to answer any questions, allocate work and help out while working the hardest among us all. His enthusiasm and stamina were amazing and extremely infectious. We would work through the day, often skipping lunch, till about 1900 h daily and then muster up at a bar outside the boatyard to unwind and go over the day’s work. By the time I reached my hotel at Portsmouth after a ferry ride and a 15 minute brisk walk I would be in danger of falling asleep under the shower!

We were quite an interesting bunch, mostly volunteers, of varied backgrounds and ages. Charlotte (Charlie), the youngest member of the team, had just finished college and was spending her summer holiday working on the boat. Timothy Ethridge (Tim), an American in his 50s, had applied to sail round the world in the Clipper Round The World Race later that year. Most of us didn’t have much technical knowledge but were willing workers, enjoying the experience and determined to do our best. That seemed fine with Robin who would always be at hand to guide us, never getting upset if we committed any mistakes, as we often did.

There were also some technicians, painters and specialists who would come and do the work while we assisted them and kept learning. I slowly graduated from sanding the boom to helping fit out equipment on the boat. Every day was a new learning experience. I was seeing a large yacht being fitted out for a round-the-world ocean race for the first time. Having been an executive officer in the Navy all my working life, I was not too conversant at working with tools; in the Navy, there is always some technical manpower available. As I worked, I became increasingly confident about using various tools and working with my hands, something that would hold me in good stead later.

I managed to get a day off in the three weeks in the UK and used half a day to catch up on my sleep and the rest of it to visit the old Portsmouth Dockyard where Nelson’s flagshipVictoryis berthed as part of a museum. Meanwhile,Grey Powerwas renamedSaga Insuranceafter Robin’s main sponsors at the Portsmouth waterfront. After a few more days of work we set out amid fanfare for Bilbao, Spain, to be on the start line for the race. As we started setting the mainsail, everything seemed to be going wrong. The mast seemed to be snaking up instead of standing upright and the swing keel wouldn’t swing! I was assigned the simplest job, that of holding the boat on course while Robin and others tried to sort the problems out. There was no alternative but to turn back. The mast and rigging needed to be tuned but the problem with the keel still foxed everyone. As Robin came to the tiller and sat down, mulling over the problem, visibly upset, I asked him if he had turned the swing keel switch to the ‘on’ position. “What switch?” he asked. I asked him to hold the tiller, ran down and put on the switch – the swing keel started working! He had been busy while we were working on the swing keel and was not aware of the switch. One more important lesson learnt: Know your boat like the back of your hand!

We finally set sail for Bilbao with a crew of six. Robin, Tim, Charlie (missing her freshers’ week for the sail), Richard, a friend of Robin and a barrister by profession, Juan, a South African sailor who had recently earned his RYA Yacht Master’s ticket, and me. At sunset and after crossing the Solent, Robin divided us into two watches for the rest of the trip. He was to head one watch and I, the other. I had never sailed a large yacht before and told him so. Cool as a cucumber, he asked, “You have a naval watch-keeping ticket, haven’t you?” “Yes”, I replied. “Well that’s more than enough. Wake me up if you feel there is a problem.” With that, he got inside the boat and went off to sleep. He did ensure that I had Juan and Richard with me on my watch, both of whom had been crewing large yachts. The boat was still far from ready; only the basic instrumentation like the compass was working as we hadn’t had the time to wire up the rest. She had to be hand steered as the autopilot was yet to be wired.

An Open 60 is quite a beast to sail; designed for speed and to withstand the extreme punishment of the Southern Ocean, there is very little thought given to crew comfort. Even a basic fitting like a toilet is missing as that would add more weight and one more opening in the hull. ‘Buck it and chuck it’ is the only solution to relieve oneself! As we crossed the shipping lanes around the UK and France and entered the Bay of Biscay, often called the Bitch of Biscay or Beast of Biscay, I realised the reason for the expletives. Strong head winds, whipping up big seas, and a boat sailing upwind at over 15 kts, heeling at an impossible angle, slamming on every wave while making noises as if she was possessed and wanted to break herself! While on watch we would get splashed every few seconds by the sea spray and the resultant cold would permeate right down to the marrow of my ‘tropical’ bones!

One night as I was lying in my bunk, having woken up to go and relieve the watch on deck, my body just refused to obey me. “How the hell did I get myself in this situation? This is not even close to the Southern Ocean, which I am expected to cross alone.” I just kept lying there for a couple of minutes, frozen in more than one way! “Misery is being on an Open 60 in the middle of a Bay of Biscay gale. Nice definition. But do I seriously want to go through with this endless madness, trying to go round the world alone?” I thought to myself. But then the incorrigible alter ego piped up, “Well, would you rather be pushing files at NHQ for the rest of your life?” I was at the tiller, fully dressed and tethered to the boat to do my watch, in the next five minutes. “Good God, what a horrible alternative that was!” Sometimes inspiration comes in strange ways.

We reached Bilbao after four days and were warmly received by the late Jose Ugarte, the legendary Spanish solo circumnavigator, among others. With only three weeks to start the race, the work on the boat continued at the same blistering pace as before. Meet at the hotel’s restaurant at 0700 h all groggy eyed and achy for a big breakfast and be on the boat by 0830 h after negotiating the traffic in an alien city with signage in an alien language. Work till about 1900 h, go over the day’s work at a bar on the Marina and get back to our hotel by 2130 h, again negotiating the unfamiliar Bilbao roads. Our tiredness and inability to read Spanish sometimes led to really funny situations. Once, hopelessly lost and finding our way back, we crossed the toll booth for a tunnel en route twice in a span of 30 minutes, from the same side!

My last name ‘Donde’, which means ‘where’ in Spanish, was a source of amusement to the Spaniards. Once Robin joked, “Hell of a prospective circumnavigator you are with a name that means ‘where’!” I told him that it actually stands for “where next”, the next having been abbreviated and that I shall sail around the world! “Well said!” said Robin with a big grin.

They were exciting times. Apart from work there were plenty of discussions with Robin about India, history and a host of subjects. He was still trying to brush up his Hindustani, which was a source of much amusement to everyone. Once, leaving for the hotel at about 2100 h, with a car full of dog-tired occupants, Robin was adamant on stopping for a haircut on the way as he was worried about not being able to get any free time later. There was almost a mutiny in the car at his suggestion. I muttered quietly to Robin in Hindi, “Robinsahib, seedhe ghar chalo warna joote padenge,haircutbaadme lena!” (Let us head home straight, else we will get thrashed; have a haircut later.) Robin just said, “Achha,” and headed straight back to the hotel with everyone wondering what exactly transpired between the two of us for Robin to abandon the plan.

I remained in touch with people back home, including Admiral Awati, Capt Contractor and the folks at NHQ who would keep airing their apprehensions which, having no knowledge on the subject, I would often pass on to Robin. One day, he couldn’t take it anymore and told me, “Indians are among the most capable people I have seen, but then why are you guys so under confident of yourselves?” His question shook me and I often mull over it, especially after the successful completion of the project, when people still cast aspersions about the ability of an Indian to undertake similar ventures. His advice for the project was really simple and to the point. In the order of priority and difficulty: “Get the funding, get a good boat and then it’s just sailing!” He couldn’t understand why we were making such a big fuss over the whole thing considering that the first time he ever sailed solo was when he started his non-stop circumnavigation way back in 1968. “Just go and sail, you will do it,” he told me. Encouraging words, when everyone at home doubted the whole idea.

On the morning of 22 Oct 2006, as we were heading for the start of the Velux 5 Oceans Race, Robin asked me if he owed me anything. He was, of course, asking if he owed me any money for the sundry items bought for the boat. Embarking on a solo circumnavigation, one likes to ensure that there are no IOUs for obvious reasons. My first response was, “No, nothing. All accounts have been settled.” As he turned his attention to something else, I blurted out, “Robin, come to think of it, you do owe me something.” Surprised, he turned back and asked, “What?” I replied, “You owe me my project!” He just smiled and told me, “Absolutely! Just let me get back.”