7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Much has been said and written about the Azov Regiment, the now infamous volunteer unit formed during the long war in the Donbas. Amid the allegations and sensationalism from both Western and Russian media stands this unique first-hand account of what life was like in the notorious independent battalion.

In

The Foreigner Group, Swedish volunteer Carolus Löfroos offers in vivid detail his experience from 2014 to 2015 among the motley crew of Azov’s foreign fighter wing. Löfroos’ insight covers the period from the Euromaidan protests to the rocket attacks on Mariupol, all the way to the skirmishes in post-Soviet backwater villages like Shyrokyne, until the cease-fire agreement in 2015. Contained in this account is an invaluable piece of history which details the long war in the Donbas, setting the stage for the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War—the latter cannot be fully understood without knowledge of the former.

Antelope Hill is privileged to present Carolus Löfroos’ colorful war memoir to an international audience. This book provides key insights into an epoch-defining conflict.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

The Foreigner Group

THE FOREIGNER GROUP

By

Carolus Löfroos

A N T E L O P E ii H I L L ii P U B L I S H I N G

Copyright © 2022 Carolus Löfroos

All rights reserved.

First printing 2022.

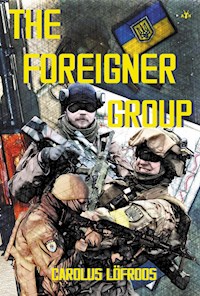

Cover art by Friedrich v. Drake.

Edited by Sebastian Durant.

Formatted by Taylor Young.

Antelope Hill Publishing

www.antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-49-5

EPUB ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-50-1

Contents

Foreword

Post-Scriptum

Map of the Mariupol area

Chapter 1: The Buildup to War

Chapter 2: Volunteering

Chapter 3: The Road to Ukraine

Chapter 4: Kyiv

Chapter 5: Stranger Among Strangers

Chapter 6: Waiting

Chapter 7: Urzuf

Chapter 8: Paranoia

Chapter 9: The Polygon

Chapter 10: Training Continues

Chapter 11: Mines at the Beach

Chapter 12: Shot at for the Cameras

Chapter 13: Search and Destroy

Chapter 14: Quality Equipment

Chapter 15: A Guardian Angel

Chapter 16: Too Much of Too Little

Chapter 17: A New Year

Chapter 18: A Darker Kyiv

Chapter 19: A New Home

Chapter 20: Forward of the Front Line

Chapter 21: Funerals

Chapter 22: Rockets Over Mariupol

Chapter 23: “Outta my face, please!”

Chapter 24: Nervous Opponents

Chapter 25: The Last Offensive

Chapter 26: Attack on Pavlopil

Chapter 27: Recon Outside Lebedynske

Chapter 28: Långström’s Raid

Chapter 29: A Big Explosion

Chapter 30: Frontline Ravefest

Chapter 31: Shyrokyne

Chapter 32: The Shelling Begins

Chapter 33: The Battle of Shyrokyne

Chapter 34: A Chaotic Retreat

Chapter 35: The Mighty Mayak

Chapter 36: A Hotel with a Sea View

Chapter 37: Back to Shyrokyne

Chapter 38: The Road to Glory

Chapter 39: Back Through the Valley

Chapter 40: The Ceasefire

Epilogue

Additional Pictures

Foreword

Most people believe memories of certain strong and powerful moments are never forgotten. I used to think so myself, especially as I’m gifted with an unusually good memory as it is. Since then, though, I have been through and seen and experienced many things which I would have thought impossible to forget, yet I have forgotten about much of it all the same.

In order to really be unable to forget something, it must be something more than just a simple memory. It has to be connected to something: the more common, the better—a taste, a sound, or a scent. Something which alone can bring you back in time to a completely different place, allowing you to meet, feel, and perceive something in reality long gone like it’s right there again.

Something as simple as the scent of freshly cut grass, for example, will always bring me back to my summers as a young boy, as will the sound of a Nintendo NES and an old television set just the same. The smell of freshly cut pine and its sweet resin will always bring me right back to when I worked in the forest with my father as a young boy. The smell of salty sea water and the bloom of algae takes me right back to the year I trained to be a Jaeger and the beautiful summers of the Finnish archipelago.

Then there is the smell of cold winter, something I know I had other memories attached to before. I don’t remember any of them anymore. Instead, that smell now always brings me to the winter in Ukraine, February of 2015. It doesn’t matter where I am or what I do, whether it’s a smoke break at work or just walking the dogs during a cold winter morning. As soon as the air hits my nostrils and I smell the winter cold, my mind brings me right back every time. It’s not without a certain feeling of unease, but overwhelmingly with an almost tearful joy. A nostalgic reunion, like meeting an old, old, and beloved friend—reliving a dream I have already once dreamed. I was the one who ate the ripest of fruit and drank the finest wine, and now I starve and thirst for them forever. Inside I cry out of fear I may never taste them again, but all the same I find myself indescribably elated knowing that I at least get to smell it once every year. I am glad I at least know what they actually taste like. As smooth as water, war has run down my throat like perfect single malt whiskey, and my tongue has tasted hot fierceness of armed combat. And I get to taste and relive it, at least a little, once each year.

Each time I feel that scent, part of me is back over there again. I stand there, feet firmly planted against the fertile but now frozen soil below. Around me lay the large, wide-open fields full of hundreds, perhaps thousands of ravens, all of them croaking loudly how nothing beyond their lands are illuminated by the star of prosperity. I am there again, as the hereditary enemy’s heavy artillery thunders by the horizon and then casts its fire down on us, making the stiff earth shake so violently that the graves are filled back in before they are even dug. Once more I can hear the raging cracks of rifle bullets striking through the air around me, and the violent sound of diesel engines and tank tracks squeaking around the next corner. The simple scent of winter fills my mind with all other kinds of smells like that of gunpowder, iron-rich blood, burned cordite, fuel, and burning houses. I can hear the sound of machine guns cycling in automatic fire, roaring engines, howling shells, and thundering explosions echoing back from inside my eardrums already rubbed by the noise. My neck stiffens and the sinewy muscles in my fingers tighten, instinctively searching for a rifle to carry.

I am at peace. I am awake, but I dream of the small village of Shyrokyne, where for a few days I was the best man I will ever be, fighting and wildly throwing myself against the rage of death, side by side with others who were exactly the same. We, simple good men bringing out the monsters inside ourselves to greet the other monsters coming against us. We who went forward with nothing to win or gain, but did so anyway simply because it was what was expected of us. Because it was what we expected from ourselves.

There has been a lot said and written about us, from all different kinds of places. About the Western volunteers who fought for Ukraine during those days. Vladimir Putin once called us a “NATO legion.” At one point, the US politician Max Rose managed to claim that we were seventeen thousand strong, citing the CIA—all of us, of course, right-wing extremists and Nazi terrorists. Who we were and what role we played have been immortalized in writing many times before, but never really by anyone who was actually there.

I was there, and even though it’s been several years since, I remember very well that we were not that many. We were just a few men, a motley crowd of warriors with different reasons to join the Foreigner Group. I began writing our story down some time ago as a sort of therapy. A way to try and free up my mind by getting all memories down on paper, leaving space for other, new ones instead. After a while, and being told this is a good story, I decided to try and make it for others to enjoy, as well. To enjoy just like I did.

Carolus Löfroos

Norrfjärden, November 12th, 2021

Post-Scriptum

A lot has happened since this manuscript was finished. The initial attempt to publish this story was met by fierce attacks from leftist political activists, often claiming that the story’s mere connection to the Azov Regiment made the book a dangerous document full of lies and Nazi propaganda. These attacks, like they often do these days, proved successful, regardless of how empty the claims were.

Then, only a mere month after the initial publishing of this book was canceled, the Russians finally (and as had long been expected) began their large-scale invasion of Ukraine. They did so as to, using Russian president Vladimir Putin’s own words, “de-Nazify Ukraine.” While I myself was surprised by the very poor choice of timing, planning, and execution of the attack, the West as a whole seemed more in shock by the invasion itself. As if they had intentionally been looking the other way for eight long years and refused to listen to those of us who all this time tried to warn them the attack would happen. As if they had completely missed the first Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began way back in 2014, and everything which had happened since.

It’s a fact that the long war in Donbas will forever be overshadowed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. I do, however, believe that nobody can understand the latter without knowing the first. It is my hope that this story not only proves an interesting read on its own, but also that it may give some much-needed understanding about not only the wars—and Ukraine and Russia themselves—but also the beginnings of the notorious Azov Regiment, which became legendary during their stubborn defense of Mariupol and the Azovstal steelworks. I will forever stand humbled, having had the great honor to fight alongside these men, and I would like to dedicate this book to the defenders of Mariupol. You will never be forgotten.

Glory to Ukraine. Glory to you, the heroes.

Also, a special thanks to everyone with whom I’ve personally served in the war, and to Robert, who kept saying I should write these stories down to paper.

Carolus Löfroos

Jämtland, August 6th, 2022

Map of the Mariupol area

Chapter 1: The Buildup to War

February 2015

The sun had not yet risen over the horizon, but the sky was already gradually starting to brighten. The fog was dense over the field that lay between the heights behind us and the ancient, picturesque little village in front.

“Shyrokyne,” I mumbled to myself. “What use do we have of these ruins, anyway?” I was then reminded that Chris was still there, somewhere, inside.

There was no snow in sight, but the tall grass and ground were nevertheless dressed in all white from the previous cold night’s frost. The breezes, smelling of fresh sea air, were interrupted at times by the smell of smoke from the smoldering houses which had burned down during yesterday’s deadly fighting. Bear jumped down off the eight-wheeled BTR-3 armored car, and a collective sigh of relief was drawn, knowing that he would not continue forward riding on its roof.

The soldiers gathered behind the T-64BV tank and the BMP-2 in a shallow ground depression in front of the entrance to the village.

“What is the plan, anyway?” I asked Långström. He looked at me glumly, then toward the village, and sighed.

“I guess it seems like we’ll just attack along that road. Fuck do I know, really?”

“That’s the plan? Just a frontal attack? It will never work. Couldn’t they come up with something better?”

Långström just shrugged. “It was you guys who wanted to do this. What do I care? You were the ones who wanted to go back in and look for Chris. I said it was pointless. There are too many Russians, regardless of whether we have a good plan or not.”

A Ukrainian assigned to the second column came walking through the fog from the other side of the road. In his hands he carried a large glass jar. The faint light from the sky shone through the jar, which glimmered in a red hue.

“He found strawberry juice in the abandoned houses?” Cuix asked with a laugh.

The starving and thirsty group cheered loudly. Fabien went first and had a hearty drink, perhaps with the hope that it could have been wine. The Greek put his AK-74 down, cleared his throat, and took a somber tone.

“My friends, gentlemen…and women. Don’t want to exclude any of you if you identify as such.” He smiled jokingly before continuing: “I just want to say that it has been an honor to serve with all of you. I’m not joking now. I am serious—I mean it. I’ve really had a great time getting to know all of you. Seriously. Honestly.”

Richter stood quietly, peering out at the village without saying anything. He observed the surroundings in complete silence without even a worried expression on his face. Not even the smell of fire and smoke made his nostrils move.

Tjeck was shaking. Not from the cold, but from fear.

“How are you doing?” Fabien asked in his thick French accent. “Are you okay? You can do this, right? It’s okay. You come with us only if you know you can do this.”

Tjeck smiled nervously and struggled to utter his words. “I think artillery is the hardest for me. That sound it makes—it is difficult for me. Enemy bullets will be easier, I think.” He stammered as he spoke, looking away. His facial muscles twitched involuntarily as he tried to squeeze out a confident smile.

I looked down the road, toward the village. The Russian force had to be twice as big as ours, and they had several armored vehicles, including tanks. We wouldn’t stand a chance. Everything from the past year had boiled down to this point, to this very moment. We had been given an impossible task, and the choice was to either back away from it and retreat, or move forward, anyway, and fail, likely dying in the process. We could not win, but we couldn’t back down, either. We would press forward and give everything we had left. We stood no chance, but in deciding to proceed regardless, we were as free as any men could ever be.

“The fog is starting to dissipate,” I said to Långström. “This clusterfuck needs to hurry the fuck up. If we are going to do this, we must do it now, otherwise they’ll bring their artillery on top of us.”

Långström looked at me and laughed. “Yeah. You take the lead position on the right side of the BMP.”

“In the very front?” I asked. “What in all the—”

“Fuck it, does it matter?” my squad leader interjected. “I’ll be right behind you. Then Bear and the Greek behind me with Tjeck, Fabs, Cuix, and Richter behind the BMP. Metro’s squad are taking the left side. Remember to keep an eye on the windows.”

Metro was a new name without a face to me, but I didn’t think much of it. I had already become comfortable with dying, but the thought of being the absolute first one to die made me uneasy.

Långström didn’t respond to my dissatisfaction and continued: “Be sure to gun down any Russian bastard you see before he manages to send an RPG into our BMP. We have to keep it alive as long as possible.”

Our BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicle started its engine. Metro’s squad was ready on the left side and we lined up on the right.

“Glory to the heroes!” cried the Greek sarcastically.

The engine exhaust heated the air next to me, making it very warm and pleasant. I dreamed of just sleeping in a warm bed again, about taking a shower in really hot water—or even better, sitting in a hot sauna. Långström tapped me on the back of my helmet, and I turned around to see what he wanted.

“We are going to die! Do you understand that?” he shouted over the engine noise.

“Yes,” I replied bitterly, “that’s pretty evident.”

Långström had finally returned to his normal combat ecstasy. He was sharpened and back on the chopping block again.

“We’re all going to die! It’s so fucking great!”

The coarse diesel engine of the fighting vehicle roared away, spewing thick white smoke just like the exhaled air from our own heated lungs. The steel tracks started squeaking, the chassis jerked backward, and our BMP began rolling forward. Forward toward the village, toward the enemy, with a squad on foot on either side. All toward a certain death. All determined to face it as men rather than retreat as cowards.

One year earlier, February 2014

The violent, black-clad Ukrainian Berkut riot police had just opened fire on the large crowd of protesters occupying Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, in central Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The number of dead and injured was unclear, but the bloody asphalt hinted that it would be many. The protests had been taking place since November 30th, 2013. They had been triggered by President Yanukovych’s sudden reversal—he had decided to scrap his plan to seek closer ties with the West and would instead seek closer economic ties with Russia. In the eastern and southern oblasts, where much of Yanukovych’s base was located, this decision was not disappointing: it was met with cheers. In contrast, Ukrainians living in western oblasts and urban areas felt cheated and greatly disappointed. Protests started in many cities, with the biggest demonstrations taking place in Kyiv. The harder these protests were repressed, the more they grew. Those that began as mere hundreds quickly became thousands, and soon grew to tens of thousands.

There had always been violence, but it definitely kicked into a new gear when the president’s guard switched from water cannons and rubber bullets to opening fire with Kalashnikovs and sniper rifles. I sat in my apartment with an old childhood friend of mine, Anders, and followed the developments via YouTube, in the company of cold beers and smoky Laphroaig.

“We really should go there,” I said.

Ordinary media discussed the crisis often, but their coverage rarely provided any serious understanding of what was going on. In addition to YouTube, only Motgift, a Swedish alternative media source, provided viewers with up-to-date information. Their Swedish correspondents, on location in and around the protests, provided daily updates. Their photographs and descriptions of people struggling to rid themselves of the Russian yoke moved me deeply, especially because of my own Finnish background.

The protests continued to increase, getting ever larger with each escalation of violence. Though many would die before it was over, Yanukovych soon fled the country. Everything seemed to end as quickly and suddenly as it had started. I felt a little bit sad over having lost the opportunity to embark on a great adventure. A great calm laid itself above the horizon, and the story seemed to be at an end. The calm, however, would soon prove false. The story hadn’t even begun yet.

While all this was going on, I was participating in the annual winter exercise with the Home Guard, the main territorial defense units of the Swedish Armed Forces. I could feel my phone vibrating in my pocket while I lay in my foxhole dug out of packed snow. There was little time to answer the call, being busy fighting off an attacking opposing enemy force. The large blank fire adaptor attached to my Ksp 58B machine gun gave off beautiful flames, flashing into the thick, wintery woodlands surrounding me.

The enemy was easily pushed back, as is the norm for such an exercise. There are clear good guys and clear bad guys, and the officers in charge decide who wins the day. One of these officers, referred to as the “blue-yellow,” did, however, declare one man in our squad as “severely wounded” during our glorious defense. The day had warmed up enough that the snow was both deep and wet. I left my machine gun in my foxhole for a weaker soldier to look after while I assisted in evacuating our casualty. While we struggled to drag the adult man through deep snow, I cursed the inopportune moment for someone to get “hit” in such a location in such conditions.

“Wouldn’t it be better if people died at more convenient times instead?” I asked the others.

After an effort involving copious amounts of swearing, we finally mounted the casualty onto a sleigh which would take him the rest of the way. I wiped the sweat from my forehead and buttoned up my snow blouse and uniform as I returned to my defensive position. The sun had shone brightly during the fighting, but by the time the evacuation was complete and I was back in my machine gun nest, it had already begun to set. The exercise was taking a brief pause, so I had the opportunity to check my phone and return that earlier call. It rang only a few times before the other line connected. Before I could ask, I heard a voice saying “Jansson is dead.”

I was stunned for a short moment before asking the caller to repeat, unsure that I had heard the message correctly. The voice just repeated the same thing. I sat myself down in the snow under a spruce, completely oblivious to my surroundings. You are never really fully prepared to hear about the death of a friend or relative, but in this particular instance, it became even stranger, even ironic.

Just days after Ukraine’s now ex-president’s escape to Russia, images of Crimea began showing up in news outlets. The large peninsula, which extended from southern Ukraine out into the Black Sea and divided it from the Sea of Azov, went from a place known only to connoisseurs of history to headline news. Crimea’s geography and milder weather had made it a popular vacation spot since the Soviet era—it also made it an ideal location for a naval base, and the Russian Federation’s Black Sea Fleet was based out of the Crimean port city of Sevastopol. Much like the United States’ operations from Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, the naval base in Sevastopol had been leased by Ukraine to Russia since the countries split apart in the early 1990s.

The media was reporting that “mysterious soldiers” had quickly begun taking control of the peninsula. The soldiers did not carry any nationality designations or insignia and were thus treated as unknowns. Anyone with a small amount of knowledge and understanding could, of course, see that these were Russian soldiers. They moved around in armored cars like the GAZ Tigr and were all wearing standard-issue Russian uniforms with the new digital Flora camouflage. Their small arms were also Russian, most notably their Pecheneg machine guns. Russia was lying outright, claiming that these soldiers were not theirs, but local self-defense forces, spontaneously organized by the population out of concern over the precarious political situation in the country. Despite this clearly being a lie, ignorant Western media hesitated to point it out. In not doing so, they not only permitted the confusion to continue, but intensified it.

Most pictures of the “little green men,” as the international media soon began to nervously call them, showed them calmy patrolling and guarding key areas. In the few cases where the green men did not wear uniforms, but civilian clothing, their equipment was even more revealing. They were described as “local rebels” and were dressed accordingly in Adidas trousers. There was not, however, enough three-striped athletic gear in the world to cover up their 43mm GM-94 pump action grenade launchers, which they wielded openly in the street during tactical movements. This weapon was not something you saw in the daily news, and the few times it did show up, it was almost exclusively in the hands of Russian special forces units. It was obvious that Russia was the main player in these events, but no one dared to say it out loud as long as official Russian sources denied it.

Vice News had previously followed and reported on the events of the Euromaidan—as the protests had come to be called—in a very professional and straightforward manner, and their reporter Simon Ostrovsky now continued these reports directly from Crimea. It became increasingly clear how Russia, taking advantage of the power vacuum in Kyiv, seized the opportunity to conquer Crimea. The most painful thing to watch by far, however, was Western media and politicians. In a mixture of incompetence and meekness, they collectively refused to even acknowledge what was going on, leaving an open goal for Russia to continue scoring into day in and day out. Ukrainian soldiers stationed in Crimea were confused and without leadership, left completely alone. The highest-ranking Ukrainian officers in Crimea had, probably for the purest of Judas silver, betrayed them and defected to the Russians. Without any orders to follow, Ukrainian soldiers and sailors were forced to give up their weapons under threat of violence.

It took only a few weeks for the Russians to hold a referendum. The polling stations were all controlled by itinerant armed men. These were no longer Russian soldiers, but more like armed gopniks—paid bandits who could perform tasks that Russian soldiers would not. Other types of bandits, fifth-columnists, and Russian sympathizers from a number of countries—including Finland, Belgium, and Bulgaria—slid around to observe the spectacle. In their respective home countries, they were, of course, well-known as tinfoil hat-wearing lowlifes and provocateurs obviously bought by the Russian state. Through Russian media, especially internationally-oriented ones like Russia Today, this pathetic lot was dressed up and made to look like a group of international independent election observers. For those who wanted to believe it, or simply didn’t know better, they certainly appeared as such. Between free grog, biscuits with Russian caviar, and “services” from expensive prostitutes, they told the cameras that the referendum—where almost 97 percent of voters voted “Yes”—was one of the fairest democratic elections they had ever seen. Just like that, Crimea—together with the strategically important naval port of Sevastopol (which was all that really mattered to Russia)—was torn from Ukraine and incorporated back into Russia without anyone really having time to grasp what happened.

The weak pope in Rome read a prayer in which he asked God to let peace rule over Ukraine, after which he let two children each release a white dove from his window in the Vatican. The birds were immediately attacked and killed by a crow and a seagull—or the two-headed eagle, if anyone dares to believe in symbolism. The pope himself patted the children on the head and led them back into his room, a perfect foreshadowing for how the outside world would respond to what was now about to happen. He had made a mediocre symbolic effort which failed in front of his very eyes. For the pope’s conscience, however, it was good enough and he withdrew from the public view, lazy and content.

As Crimea was changing flags, I was visiting the Åland Islands, located between Sweden and Finland. My best friend from my Finnish military service, Jansson, had unexpectedly and suddenly passed away and was about to be lowered into the ground. I had written a short obituary for him containing the following:

I always felt great security and honor in knowing that if war was to come, I would fight shoulder to shoulder and eye for an eye by your side. And now, suddenly, you, the one among us who led with the highest courage, the most honest mind, and the kindest heart, are gone. The one among us who was most immortal no longer exists.

After the song and hymn, the coffin was carried out to the cemetery to be lowered into the ground. Jansson had been the sniper team commander in our Coastal Jaeger company, and even after we left the service, his interest in that particular subject had remained strong. He had talked for a long time about how he would one day buy a TRG-42 in .338 Lapua Magnum just like the one he had as a sniper in the army. Together with the roses of the other mourners, I threw down a Lapua Magnum cartridge as the coffin was lowered into the ground.

After greeting and thanking his relatives and friends, I went back to the grave once the mourners had left. I just sat next to my friend and opened the small bottle of Lagavulin I had inside my jacket pocket, which we shared together.

We had always agreed that we belonged to a minority that perhaps had a slightly greater interest in war than the average person, but without becoming completely obsessed with it. Even after we went civilian, we had strived to greet each other from time to time to drink Pilsner and talk about how much we looked forward to one day fighting a war against the Russians together. We would go over how we would beat them and plunder everything they held dear. We would, most of all, take back what was rightfully ours—Karelia, Vyborg, Petsamo, and all those other places which had long since been stolen. We joked and joyously dreamed of reconquest. Perhaps we dreamed of even more, maybe even Greater Finland.

It was March, and most of the snow had already melted away. The still somewhat cold breeze was offset by both the sun’s rays and the good whiskey. I told Jansson that I thought it was a shame that he did something as stupid as dying at a time like this, when our boyhood dreams seemed to be approaching by leaps and bounds. Jansson did not respond. The entire time that I sat there with him, I had a constant feeling that he was ashamed. I took another swig of our good single malt and poured the last one out for him before getting up. I told him I missed him now and always would. I snapped my heels in front of the grave, gave him a stern salute, and turned away, leaving my friend for the last time.

I made my way back to the Finnish mainland. At my uncle’s house in the countryside, which happened to be my mother’s old parental home, I helped with spring cleaning by hauling out garbage and old furniture and throwing it into a fire outside. I then took the tram from Karis toward Hanko as Jansson and I had done so many times before, getting off at the Dragsvik stop. I passed by the Uusimaa Brigade’s garrison area, walked toward and through the nearby training area and the Galoppskogen and Baggby shooting ranges. With the exception of some XA-180 Pasi armored cars and other military vehicles scattered about, the forest was empty.

I passed by old foxholes where we had learned basic infantry combat skills, as well as the small clearing where seven years earlier Lieutenant Westerholm, under vague rape threats, forced us to partake in strange CS gas rituals. I passed the small bushes where Jansson threw me off his back, just before he collapsed himself, after having carried me while running in full CBRN equipment under the hot summer sun. It was a great trip down memory lane.

I sat down next to one of the foxholes to rest my feet and picked up a few 7.62x39 rounds lying in the sand. I moved them around in the palm of my hand, felt the aged brass against my skin. There were a lot of memories collected in this otherwise inconsequential and bland little forest. Everything we had done here, everything we learned. Why did we learn it? Was it all for nothing, or would all this knowledge eventually be used? And if so, how? And when?

Meanwhile, in Ukraine, unrest was beginning to flare up more and more, especially in the eastern parts of the country. It was said that the regions with Russian majorities wanted to break away from Ukraine and become part of Russia, much like Crimea had done. Protests turned into riots and organized street brawls. It began to look as if the whole of eastern Ukraine, complete with its important industrial base, would be conquered in the same way as Crimea, for Russia’s greater geopolitical pleasure. The scenario was the same, but the conditions were very different. Crimea was a surprise, where no one had time to react, but this time, the element of surprise was gone. Large numbers of Russian “little green men” would be unable to play a role, since there was no longer any easy or covert way to bring them into the Ukrainian mainland.

The well-oiled planning and preparation that characterized the Crimean operation had been replaced by chaos, and the green men had been replaced by two main groups. The first was a large but completely disorganized civilian mob fueled by the propaganda spread by Russian-language media. Its most powerful weapon was the lie that “fascists,” as the Ukrainians in the west were now called, wanted to ethnically cleanse Russians from Ukraine. The mob soon took on a life of its own and proved extremely difficult to control. The second group was composed of cells of criminal bandits led by Russian intelligence services and special forces operators. They carried out strategic operations in the wake of the chaos created by the wild mob, taking over strategic locations such as police stations and government buildings.Even though the Russians no longer had the element of surprise, the Ukrainian military was unable to restore order. The effects of twenty years of decay, often caused deliberately by a corrupt and Russian-influenced political leadership, were palpable. Even the simplest security challenges proved insurmountable for the poorly trained soldiers and their completely incompetent leadership and organization.

At home in Sweden, summer was closing in, and it was once again time for the second annual Home Guard exercise, the largest of the year. This year, it would take place at the shooting ranges outside Härnösand. The focus this year was on having soldiers qualify on the Ak 4B rifle, so life was simple, albeit somewhat boring. As one might have expected, the situation in Ukraine was a recurring theme of discussion. Just about everyone understood that Russia was about to try to seize the eastern parts of Ukraine, if not the entire country. The tone was nervous, but also cheerful. We joked about the possibility of going to war if the situation escalated. Would it be in Sweden, or maybe Finland? Maybe even Ukraine proper—who could know for certain?

In Ukraine, more and more volunteer units were beginning to take shape. As the regular military—and by extension, the state itself—failed in their core tasks, free and independent men created their own militias to fill the vacuum. While Swedish alternative media like Motgift had begun to reduce their Ukraine coverage, a group of Swedish volunteers remained in Ukraine. From this group, a small number of activists had enlisted in the so-called volunteer battalions. In addition to the Right Sector (a broad coalition of right-wing groups that had been an important player during the Euromaidan), many other independent groups were beginning to form their own battalions. Swedish volunteers had particularly close ties to two of these: Aidar and Azov. Both groups were very small, and while the total number of volunteers is difficult to estimate, it was clear that none of these so-called battalions were battalion-sized. These humble beginnings would not last long, however, and their numbers would quickly increase in the coming months.

Aidar and Azov, along with many other independent battalions, quickly began operating in the Wild West that was eastern Ukraine. They provided general support to the military but were primarily deployed to the more dangerous sectors. Where there was a serious risk of violence, the military would simply fail to follow orders, mostly because they didn’t trust their chain of command. The volunteer battalions, on the other hand, were driven by a self-confidence that stemmed from their fervent Ukrainian nationalism. This confidence allowed them to not just put up a hard fight, but, most importantly, it allowed them to make difficult decisions that the bloated and poorly led military could not. While heavy weaponry remained with the Ukrainian military, the volunteer battalions became their reaction force, momentum and, in practice, their real leaders and the spearhead at the front.

As the summer reached its peak, I was once again attending another Home Guard exercise. The situation in Ukraine had escalated in recent months, along with the tone among the soldiers. Many believed it was incomprehensible that no one was helping Ukraine put an end to the situation, essentially giving Russia free reign. The EU countries had issued strong declarations of solidarity, but nothing more. In heated discussions, increasing numbers of Swedish military personnel begun comparing Ukraine’s situation with that of Finland in 1939—few people, aside from Swedes, had volunteered to help Finland during their 105-day Winter War against the Soviet Union. While the conflict in Ukraine was not yet a real war—just an insurgency, rather—the language was clear. Many would stand with Ukraine if the situation deteriorated further. This sentiment was no longer just hinted at, it was outright stated. “Together with the EU and NATO, we must back Ukraine,” was a common opinion, and many were willing to back this up with action, should a real war ever materialize.

By late summer, the Ukrainian military and the volunteer battalions were slowly beginning to regain control of the situation. While the Russians had hoped to seize all the important cities of eastern Ukraine, in most urban centers, the pro-Russian mob had been met by an equally strong or stronger pro-Ukrainian equivalent. In others, pro-Russian elements had only barely succeeded in taking power, only to be quickly driven out when the volunteer battalions arrived. Ukraine had soon recaptured almost all their territory in the east. The pro-Russian mob and the bandit force, now calling themselves “separatists,” had only managed to gain a real foothold in two cities—Luhansk and Donetsk. The war seemed to be over before it even began. Then, once again, something unexpected happened that changed everything.

Reports began trickling in of heavy shelling of Ukrainian positions from the Russian side of the border. In use were all types of heavy artillery, including the extremely destructive MLRS rocket artillery. The bombardment forced Ukrainian troops out of border regions and left the borders completely undefended. Then, seemingly out of the ether, the “separatists” that had once been equipped with small arms were now rolling around in tanks and other types of heavy equipment. In reality, these “separatists” were regular Russian units—a desperate attempt to take back the initiative in a quickly deteriorating situation. Now, with this action, the Russian-backed insurgency had escalated into what was essentially a “real war” between Ukraine and Russia. In the ensuing chaos, Ukrainian units were quickly forced back, taking huge losses in a very short period of time. Russian artillery bombardments were in some areas so intense that they reportedly wiped out entire companies and battalions—hundreds of men—in minutes. In rapid bursts of flame, both tanks and men were transformed into distorted piles of metal, flesh, and ash. With each passing hour, the inexorable slaughter continued.

In August, the Russians encircled the Ukrainians in the small town of Ilovaisk, located between the separatist stronghold of Donetsk and the Russian border. The Ukrainian force was virtually annihilated. Nearly two-thirds of the one thousand men surrounded there were killed or injured. Large amounts of Ukrainian military equipment were either destroyed or abandoned. The Azov Battalion, which by now had grown in size to resemble a real battalion, managed to break out of this pocket before it was too late. But for the Aidar Battalion, things did not go so well. I could find photographs taken by their enemies showing Aidar soldiers being ambushed during their retreat. Around their burning trucks on the hot summer asphalt lay burned and mutilated naked bodies. The “separatists,” who were not Russian-speaking Ukrainians, but mercenaries from other countries (particularly Russia), proudly posed next to their contorted remains. They took their time desecrating the corpses, cutting off their ears and disfiguring their faces, clearly taking great pleasure in it.

Both Jansson and I had tattooed the Finnish Coastal Jaeger insignia, the golden head of a white-tailed sea eagle, on our upper arms. We did this partly to commemorate this part of our lives and partly out of pride from having overcome the rigors of military life. Primarily, it served as a reminder to never be a coward when it really matters. The Coastal Jaegers had trained us to always go first and foremost, regardless of the risk to our own lives. As non-commissioned officers, it was particularly important to be the ones who lead, the ones who step up to a challenge when no one else dares. During wartime, the Coastal Jaegers were supposed to step up whenever the otherwise competent Finnish navy could no longer cope. During our last and final exercise in Finland, we were ordered to attack part of the Armored Brigade. It is well-known that light infantry, as we were, has difficulty defending against heavy infantry and armor. Having light infantry attack armor seemed crazy indeed, especially considering that we barely carried enough APILAS anti-tank weapons to destroy their tanks and fighting vehicles. The point of the exercise was not to achieve victory, however. Rather, it was to imbue the men with an aggressive mindset and to put them at ease with the idea of unquestioningly taking part in a fight they know cannot be won.

Seeing brave but unprepared Ukrainian soldiers slaughtered while resisting a vastly superior force was the final straw for me. Everyone talked loudly about how they would do something, how they, too, would help the Ukrainians, if only the circumstances were right. Everyone talked about how EU countries, NATO member states, and the United States should do something. But now, as burned and desecrated corpses lay smoldering on the asphalt outside Ilovaisk, they only continued to offer excuses. “Someone else needs to do something,” was a common refrain. I looked in the mirror and did not see myself anymore. I only saw a member of the gray, cowardly masses offering excuses, and I refused to continue being a part of it. I knew that if I gave in to cowardice in this moment and did not go join that war, I would be just like the others and never amount to anything. I would forever be a fake person, a fake soldier, and a fake Coastal Jaeger.

During the Euromaidan, I entertained the idea of a quick in-and-out, twenty-minute adventure. It never really caught my attention, however, and was over before I could seriously consider the notion. During the initial stages of the conflict in eastern Ukraine, the motivation was the same: a desire for adventure, but the Ukrainians seemingly took control of the situation rather quickly. There was no point in throwing away a fairly good life just to play a part in the final chorus. The temptation was always there, but the motivation to embark on an adventure had never been sufficient.

Ilovaisk was the turning point for me. Thousands of brave but ill-equipped Ukrainian soldiers broke before a now overpowering enemy. Figures were circulating that claimed that more than half of the regular Ukrainian military was destroyed. They were on their own, despite all the supportive talk from high-ranking politicians, the pope, and my friends in the Home Guard. They only offered empty words, and I couldn’t stand for it.

It was like a fire raging within me. I didn’t understand where it came from, but I had no choice but to follow it. I knew that I belonged in the war much more than I belonged in Sweden, spending my days waiting for the next meaningless Home Guard exercise. For the first time in my life, I knew I was going to go to war, and I knew it would be soon.

Chapter 2: Volunteering

I began inquiring about which Ukrainian units I could apply for. I initially looked at the regular military but gave up on them fairly quickly. The terrible impression I had of their performance so far in the war was only boosted by unclear messaging and their lack of effective communication with potential volunteers. Anyone could see that their enormous losses since the Russian incursion could not be attributed simply to the Russians’ superior equipment and numbers. It was obvious that their poor performance was at least partially explained by their lack of organization and training, as well as sheer incompetence.

I then turned my attention to the independent volunteer battalions. Most were based on or were directly linked to Right Sector. Here, too, communication was difficult, and I had trouble finding clear information about volunteering. Instead of trying to get answers from Ukrainians, I turned to Westerners that I knew had become heavily involved in Ukraine. By pure luck, I had come across an anonymous Swedish man on social media that was currently serving in the Aidar Battalion. He provided guidance on how I could volunteer for the unit—it was surprisingly easy. You had to travel to Kyiv at your own expense, look for people associated with the battalion, and inform them of your intention to join. The battalion would then provide you with arms and send you into the conflict zone to rendezvous with your assigned unit. Aidar would allow just about anyone to join, as long as he provided his own basic equipment and was physically able.

The last part was good to know, but also worrying. I never asked him directly, but it was obvious that the Swede I was speaking to was younger than me. Between the lines, it was evident that he had some military background and experience, but it was limited. I wanted to serve with professionals, not amateurs.

The Azov Battalion had long been open to accepting foreign nationals, but had emphasized the need for these to be professionals. This was well-known in Sweden, as several columns had been written about the battalion, and among the Swedish “right-wing extremists” that had enlisted in its ranks. It was also easy to find in Azov’s own official channels, which were readily accessible online.

Descriptions of Azov volunteers in Swedish media were numerous and problematic. Sweden was headed toward the 2014 parliamentary elections, and political observers predicted that the nationalist, right-wing Sweden Democrats would be even more successful than they had been in the 2010 election. The 2010 election had shocked the media and political establishment to its core, and they were determined to do everything possible to prevent it from happening again. To frighten the public, corrupt Swedish media wrote extensively about the “threat” from the far right.

Making things more difficult for the Swedish Azov volunteers was the ongoing phenomenon of the Islamic State, which in 2014 was living through its golden age. Muslims from all over the world had traveled to Syria and Iraq to volunteer, including many immigrants living in Sweden. The official number of so-called “Islamic State travelers” reached three hundred in 2013, the last year official statistics were kept. In all likelihood, the responsible government agencies stopped publishing their data once they noticed that it had damaged public confidence in established parties and greatly benefited the immigration-critical Sweden Democrats. To shift public attention away from the Islamic State and immigration, authorities and their media puppets began focusing on Azov and its many Swedish volunteers. The idea was to paint nationalists, as well as the Sweden Democrats, as dangerous extremists akin to the Muslim immigrants that had fought for the Islamic State. Hardly a single story was written about the Islamic State or Islamist terrorism without Ukraine and the danger posed by Azov’s Swedish volunteers being mentioned.

I could maybe get away with joining the regular Ukrainian military, but if I chose to join Azov, my life would never be the same again. I would be lumped in with the media narrative of “Nazis” and right-wing extremists and essentially become a “white jihadist,” as the volunteers were sometimes called. It was likely that I would never be able to get a normal job again, and I would even be exposing myself to possible criminal charges. Was I willing to face terrorism charges in order to help Ukraine and participate in the war as a volunteer?

I reasoned that the main threat was going to be Russian bullets and artillery, certainly more than being called a “Nazi” in the papers. Azov was not just the easiest unit to apply for, it also gave me the impression that it was a disciplined military force, at least compared to other volunteer units. They had made a name for themselves in the battle for Mariupol, a large city in southern Ukraine. The Ukrainian military had made little progress in retaking the city until Azov arrived and, serving as the volunteer spearhead, helped achieve victory. They also had managed to escape the devastating encirclement in Ilovaisk, potentially showing that Azov had a strategically skilled leadership. Additionally, there were many foreign volunteers in the battalion. Certainly not as many as the media had claimed in order to amplify the imaginary right-wing threat, but it had to be more than a handful. This meant that other Western volunteers had managed to serve in the unit without speaking Ukrainian or Russian. I anticipated that I could do the same.

With these calculations, I had made up my mind. Azov was the most suitable unit to apply for, and so that’s where I would start. Now it was just a matter of finding out if they would have me.

The Swede who had become the media’s poster boy for foreign volunteers in Azov was named Mike. According to the newspapers, he had been a long-time professional soldier in the Swedish Armed Forces, where he had served as a sniper for some time. He had been involved with Azov since the beginning of the war and seemed to have some sort of lower leadership role within the battalion. I had occasionally chatted with him to seek first-hand information about events in Ukraine. Now I asked how I could volunteer for his unit.

He answered quickly, and after a few short follow-up questions, I felt that I knew everything I needed to know. Azov sought both combatants and instructors (to train their Ukrainian recruits), and the terms were similar to Aidar’s—the battalion would provide food and a rifle; everything else would be my responsibility. I was told to contact the acting coordinator of foreign volunteers, a veteran of the French Foreign Legion that had previously fought with the Croatians in the Yugoslav Wars. Gaston, as he was called, needed some kind of military resume to determine if I had the required skills and experience. I quickly typed one out and emailed it to him:

General:

Age: 25 years. Military rank: Sergeant. Physical condition: Capable, healthy in general.

Military background:

Finland: Conscription service with the Uusimaa Brigade in 2007, followed by non-commissioned officer training, and then Coastal Jaeger squad leader with a focus in anti-tank combat. Also served as an instructor. One year in total.

Sweden: Guardsman rifleman with the Medelpad Battalion, later machine gunner and squad leader. Also served as an instructor. Six years in total.

Other: Engaged in hunting and recreational shooting for many years.

And that was it. I looked at what I had managed to put together and felt that it might not look like much to the world, but I hoped for the best.

Anders, my friend and fellow Maidan enthusiast, one day went out to a shooting range. It was essentially just a large gravel pit, far outside civilization, where we could usually conduct our business relatively undisturbed. We had talked about Ukraine several times before, and he had been somewhat cautiously interested in it. However, our personal lives had developed very differently, and he now had his first child on the way. He was no longer interested, though he had a difficult time in saying so.

Aside from zeroing the old Weaver scope on my German .300 Winchester Magnum bolt-action rifle to prepare for moose season, I had no particular reason for being at the range. Anders was trying out some new handloads, but at six hundred meters instead of my eighty. As he climbed to the edge of the pit to shoot down toward the targets, I stayed near them. There were large piles of timber stacked along the roads passing through the pit. Occasionally, a car or some old lady walking her dog would come this way, and the rifleman would be unable to see them. Therefore, it was necessary to maintain radio contact between the ground spotter and the rifleman situated above, to warn him about movement around the target area.

The range was clear, and I gave Anders the go-ahead to start firing. He started with his Remington 700 in .308 Winchester and then stepped it up to the TRG-42 in .338 Lapua Magnum. The sound of the bullets cracked like whips as they passed above me. I tried to take in as much of it as possible from my place down in the pit. I turned in different directions to see if it was possible to hear differences in a bullet’s direction. I moved from open terrain to between the timber lengths to see if the surroundings had any effect on the bullets’ sounds. I cupped my hands over my ears to imitate the effect of wearing a helmet. It was indeed very easy to hear differences in a bullet’s angle and point of origin, as well as the difference between calibers. The .308 wasn’t nearly as loud as the heavier Lapua rounds.

When I got home from the range, I found that I had received an email response. My nervousness subsided pretty quickly as I saw that Gaston had found my military background perfectly adequate. I was approved for service and combat. All I needed to do was travel to Kyiv with as much of my equipment as possible. From there, I was to contact him again for further instructions. Suddenly, I was in the clear. I was in. All I needed to arrange now were the logistics and travel practicalities, as well as, it would turn out, spiritual matters.

My salary as a volunteer would be small or non-existent. I had some savings but not enough to last very long. To create a financial nest egg for myself, I began selling off things that I had accumulated over the years. The possession that I got the most money for, but also felt the worst to let go of, was my revolver. It was an antique and permit-free, yet fully functional .44 caliber Remington New Model Army, often incorrectly called a Model 1858. With mixed parts and worn markings, it was not exactly in the finest condition, serving as more of a beater or a “fun gun.” After a few shameful offers, I finally received a reasonable price proposal, and in just a simple handshake I added another twelve thousand Swedish krona to my little war budget.

Through Mike, I had been told that the battalion could provide me with a combat vest and bulletproof plates if I didn’t already have some. It would also be possible to buy other equipment on location in Ukraine if I did not wish to haul everything all the way from Sweden. Above all, I learned that Ukraine was damn hot in the summer, and I made sure to take this into account when ordering clothes and other equipment online. Ukrainian soldiers did not have a strict uniform system, and their clothes were often military surplus from other countries. Looking at pictures of Ukraine’s terrain, I judged that the most appropriate camouflage pattern would be similar to MultiCam, which was, unsurprisingly, already a common choice in Azov. The British frequently used MultiCam, and since they would often sell off surplus in near-new condition, I managed to get a good deal on a uniform set from the Finnish surplus store, Varusteleka.

It was a little embarrassing when, in early September, I showed up to the annual moose hunt dressed as some kind of military LARPer. It was, however, as good of a field test for my equipment as I would be able to get. I wished to spend my time in the forests of Jämtland evaluating my shoes or clothing and correcting any fit or chafing issues. It was certainly preferable to anticipate and correct problems here than having to do it on the Ukrainian steppe. Moose hunting (as we do it, anyway) is not entirely different from war. It’s a lot of early mornings and waiting around, often in cold winds without very much happening. Then, in sudden bursts, we would hear the sounds of gunshots, which were sometimes followed by bloodshed. The time between the sudden bursts of action gave me plenty of time to think.

I mostly thought about death. I constantly found myself thinking about every possible way I could die, how it would happen, and how it would feel. I could be stricken by a bullet, for example. I could spend my final moments watching myself bleed to death through a large groin wound with no help in sight. Perhaps I would get my leg blown off by a mine? The pain would come first, then panic. I would start losing body temperature as the blood left my body, until I was finally embraced by the darkness. I could get hit by bullets in all kinds of places. Maybe in the stomach, or some other important internal organ? I pressed my fingers into my liver and wondered how painful it would be to have it pierced by a piece of hot copper-jacketed bullet.

There were other ways to die than bullets. Artillery was a common battlefield weapon, and, during a botched light mortar exercise during my conscription, I had heard and seen how hot shrapnel could tear violently through otherwise tough tree trunks. The Russians were also using thermobaric weapons—basically flamethrowers. I wondered what it would be like to burn to death, how terrifying it would be to go out that way. Perhaps I would be the lucky guy who simply got hit in the head and was done with it all in less than a moment, but if so, then what? What would come after the darkness?

In vain, I tried to understand things completely unimaginable. In my head, I went through dozens, maybe even hundreds, of different scenarios related to my possible death, endlessly trying to come to terms with each one of them. If I died in Ukraine, I wouldn’t even have the chance to see the new Mad Max movie, set to come out in 2015. I had actually been looking forward to that.

My reasoning was that these mental exercises would make me more prepared for the coming journey, not just in the specific events I imagined, but in any scenario where I would have to face the risk of death. I knew that when discipline is lost and panic takes over, all is lost—doesn’t matter if it’s an individual soldier or an entire army. Medieval armies sustained the majority of their casualties not during a battle’s organized combat, but after, as soldiers panicked and fled, only to be run down by enemy cavalry. Similarly, line infantry suffered the most—not from the hail of enemy bullets, but when their ranks broke down and the soldiers dispersed. Modern-era infantry were most vulnerable when they were pinned down by enemy fire, unable to muster the courage to respond to it. Even though it was a terrible feeling, I would prefer to deal with the panic and anxiety sooner rather than later. If I had that part resolved, I thought I would have a better chance of coping through future situations. It’s still difficult to describe, but I saw it as a personal “Golgotha walk” that I needed to complete to become an effective and disciplined soldier.

After my decision to volunteer, I tried to meet with as many friends and family as I could in Sweden. It was important to me, even though very few of them knew about my plans. Next, I intended to return to Finland to do the same thing there. The plan was to take an early morning bus from my small northern hometown of Sundsvall to Stockholm, where a ferry would take me to Helsinki. There, I had arranged to meet some old friends from the army and quit my job.