11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

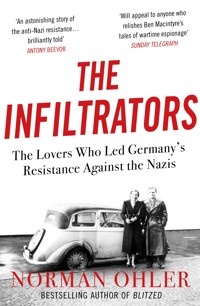

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A Daily Telegraph History Book of the Year 'An astonishing story... brilliantly told' Antony Beevor 'Gripping... Will appeal to anyone who relishes Ben Macintyre's tales of wartime espionage and cryptic codes.' Sunday Telegraph 'A detailed and meticulously researched tale about a pair of young German resisters thatreads like a thriller.' New York Times 'Deeply engaging, enticingly written and extremely affecting.' Philippe Sands, Spectator Summertime, 1935. On a lake near Berlin, a young man is out sailing when he glimpses a woman reclining in the prow of a passing boat. Their eyes meet - and one of history's greatest conspiracies is born. Harro Schulze-Boysen had already shed blood in the fight against Nazism by the time he and Libertas Haas-Heye began their whirlwind romance. She joined the cause, and soon the two lovers were leading a network of antifascists that stretched across Berlin's bohemian underworld. Harro himself infiltrated German intelligence and began funnelling Nazi battle plans to the Allies, including the details of Hitler's surprise attack on the Soviet Union. But nothing could prepare Harro and Libertas for the betrayals they would suffer in this war of secrets - a struggle in which friend could be indistinguishable from foe. Drawing on unpublished diaries, letters and Gestapo files, Norman Ohler spins an unforgettable tale of love, heroism and sacrifice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The

INFILTRATORS

Norman Ohler is an award-winning novelist and screenwriter. He is the author of the New York Times bestseller Blitzed, as well as the novels Die Quotenmaschine (the world’s first hypertext novel), Mitte and Stadt des Goldes (translated into English as Ponte City). He lives in Berlin.

‘The Infiltrators is an astonishing story of the anti-Nazi resistance – a story of love, incredible bravery and self-sacrifice, which could end only in death – and it is brilliantly told.’ Antony Beevor, bestselling author of The Second World War

‘Deeply engaging, enticingly written and extremely affecting… Original and fascinating… This is a remarkable story, powerfully told, of love and courage and of the balance in the relationship between a couple… A timely reminder of what some citizens are willing to do in the face of autocracy and oppression that once again haunts our times.’ Philippe Sands, Spectator

‘Gripping… Will appeal to anyone who relishes Ben Macintyre’s tales of wartime espionage and cryptic codes, underpinned by terrifying risk, desperate courage, and double dealing… Moving at a cracking pace through a succession of snapshot cross-cut chapters, it is ripe for transformation into a film or television series. But great heroism is properly honoured here: Ohler has done his research diligently and he has an enthralling story to tell.’ Sunday Telegraph

‘Ohler masterfully establishes his trustworthiness as a narrator, which is crucial as we travel with him back to the 1930s and then on through the war. He weaves a detailed and meticulously researched tale about a pair of young German resisters that reads like a thriller.’ New York Times

‘Lively… Ohler has given vim to the historical narrative, restored humanity and a genuine love story to the communist canonisation of Schulze-Boysen.’ The Times

‘The Infiltrators describes an idealistic young German couple, Harro Schulze-Boysen and Libertas Haas-Heye who set up an anti-fascist network that burrowed deep into Nazi society and leaked to the Allies. With depressing inevitability, betrayal and merciless punishment intervened – but this is nonetheless an uplifting tale of heroism.’ Simon Heffer, ‘History Books of the Year’, Daily Telegraph

‘An unforgettable portrait of two young lovers and their circle of friends in the anti-Hitler resistance, The Infiltrators offers a fascinating glimpse of life in Nazi Germany, where the simple self-assertion of youth was a political act, and daily life was a minefield where missteps could have fatal consequences.’ Joseph Kanon, bestselling author of Leaving Berlin

‘A thrilling and urgent true story. Inside Nazi Germany, as tyranny spreads, a few friends decide to resist, and a secret circle of anti-fascists starts to grow. They are not mythic heroes but instead flawed humans struggling for meaning in a time of terror: writers, artists, a fashion designer, a dentist. With skill and passion, Norman Ohler brings these remarkable men and women back to life. The Infiltrators is a gift of a book – one I feel a little stronger, a little braver, after reading.’ Jason Fagone, bestselling author of The Woman Who Smashed Codes

‘Ohler creates a taut, absorbing tale of anti-Nazi resistance. Told in the present tense, the narrative conveys a sense of immediacy and encroaching terror… Sharply drawn characters enliven a tragic history.’ Kirkus Reviews

‘The fascinating and tragic tale of a ragtag, idealistic crew of nonconformists hiding in plain sight while secretly working to fight the Nazis from within… This unbelievable yet true story is richly detailed thanks to the participation of descendants of these courageous resistance fighters; with their help, Ohler succeeds in vividly thwarting the Nazis’ attempts to erase these heroes from history.’ Booklist

‘This deeply researched and stylishly written account unearths an appealing yet overlooked chapter in WWII history. Espionage enthusiasts will be riveted.’ Publishers Weekly

‘Remarkable… Vivid and engaging.’ Times Literary Supplement

‘The Infiltrators paints a picture of a marriage of intellectual equals who are driven by a single shared cause: to bring down the Nazis from within. In telling this story the book draws on diaries, letters and Gestapo files, many of which are previously unpublished, bringing much greater detail to an otherwise known but under-reported story… Gripping.’ All About History

‘Norman Ohler has achieved a historically significant work of discovery with great literary skill.’ Augsburger Allgemeine

‘Norman Ohler has told the story in the form of a gripping thriller… although Ohler’s book reads like a crime novel, everything in it did actually happen.’ Berliner Zeitung

‘Very well researched… unbelievably gripping… a page turner… A remarkable book about two remarkable resistance Red Orchestra fighters.’ Deutschlandfunk Kultur

‘A powerful and swift read, racing along like an expressionistic railway, but every sentence is also threaded with intelligence and empathy.’ Die Welt

‘Such a subject could not fail to arouse the interest of Norman Ohler. The journalist who demonstrated his mastery of investigative nonfiction in Blitzed… finds here historical material which he recounts as a thriller.’ Livres Hebdo

‘With the help of new archives and with the pace of an addictive thriller Norman Ohler rebuilds their resistance ensuring them a posthumous victory which will not be forgotten.’ O.C. Le Nouveau Magazine Litteraire

ALSO BY NORMAN OHLER

Blitzed

Published by arrangement with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Norman Ohler, 2020

Translation copyright © Tim Mohr and Marshall Yarbrough, 2020

The moral right of Norman Ohler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Excerpts of unpublished letters accessed through the Red Orchestra Collection at the German Resistance Memorial Center and the archives at the Institute for Contemporary History. Used in English translation by kind permission of E. Schulze-Boysen.

Illustration credits: All images reproduced by permission of the German Resistance Memorial Center, Berlin, with the following exceptions: page 11, “Guillaume: Leurs Silhouette No. 9” by Orens, October 11, 1908; page 42, bpk-Bildagentur; page 131, Gyula Pap/Design and Artists Copyright Society; pages 64, 156, 215, 221, Bundesarchiv.

Book design by Margaret Rosewitz

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-212-9

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-83895-213-6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For the kids

It would make an amazing story if it weren’t so illegal.

— A GESTAPO OFFICER

To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize “how it really was.” It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger.

— WALTER BENJAMIN, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

CONTENTS

Foreword

PROLOGUE: The Thick of It

PART I: Adversaries (1932–33)

PART II: Work and Marriage (1933–39)

PART III: Resistance and Love (1939–42)

PART IV: The Black Curtain (Fall 1942)

EPILOGUE: Restitutio Memoriae

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

FOREWORD

1

When I was about twelve years old, I was sitting in the garden of my grandparents’ house, set in a valley on the outskirts of a small city in southwest Germany, near the border with French Lorraine. In March 1945 the town, which was also the place of my birth, was leveled by the British and Canadian Royal Air Force, with more than 90 percent of the baroque buildings destroyed. My grandmother and grandfather fared the same as almost everyone else: nothing of their home survived the hail of bombs. So my grandfather built a new house after the war “out of rubble,” with his “own hands.” He dubbed it Haus Morgensonne, or the House of the Morning Sun, and the gravel road that led there he named Wiesengrund, or Meadowland, and it was later labeled as such on official maps.

We often played a board game called Mensch Ärgere Dich Nicht (Man, Don’t Worry), similar to Sorry, in the garden of the House of the Morning Sun. Before the dice were rolled my grandfather usually said, “Play hard but fair!” This directive scared me a bit, even though I had nothing against fair play and he wasn’t particularly serious about playing hard, since, after all, we were only trying to have as much fun as possible while passing the time. But on this particular afternoon, fair or unfair, I refused to roll the dice until he told me a story about the war. We’d seen a documentary that morning at school about the liberation of a concentration camp, the piles of eyeglasses, the emaciated faces, cutting effectively to shots of jubilant Germans hailing Hitler. Not a single pupil was allowed to leave the room before the film was over.

So I wanted to know whether my grandfather had anything to do with all of it. At first he shook his head and wanted to start playing the game. But I took the two ivory-colored dice and looked at him searchingly. Mottled sunlight shone through the leaves of the apple tree and cast a pattern of light and shadow on the yellow game board. He explained he had been working for the Reichsbahn, the German railway. That wasn’t news to me, and I pressed him to tell me something interesting, something concrete.

Lost in thought, he stared at the evergreen trees that lined the edge of the meadow. Then he coughed. Finally he slowly and casually said that he’d been a true and avid railroader because he’d always loved the reliability and precision of the railroads. And that he could never have imagined what was going to happen. I immediately asked: What happened? Hesitantly, he told me that he’d been working as an engineer — did I know what an engineer was? Even though I didn’t really know exactly, I nodded. During the war, he continued, he’d been transferred to the northern Bohemian town of Brüx, a hole at the junction of the Aussig-Komotau, Pilsen-Priesen, and Prague-Dux lines.

One winter evening, as fresh snow covered the black double lines of the tracks, as well as the meadow, the trees, and the frozen Eger River, an arriving train was shunted onto a siding, my grandfather said with a halting voice, a long freighter with stock cars that had to let a munitions transport pass. Wheels screeched as they crossed the shunting switch, calls rang out, a long whistle. Steam billowed and dissipated. The stock cars were uncoupled. Silence descended on the white-covered valley again.

But something wasn’t right. My grandfather felt it; his railroader instincts told him. After a while he left his little station house and approached the siding. The only thing audible was the gurgling water of the Eger flowing beneath its frozen surface. Uneasy, he walked along the entire row of cars. Just as he went to turn away, something moved in one of the narrow ventilation slits on the upper half of a sliding door on one of the cars. A tin cup on a string was lowered from the opening, clanged against the wood of the side of the car, got stuck on the door handle, broke free, and then dangled slowly down and dipped into the snow next to the tracks. A moment later the string tightened and pulled the filled vessel back up. A child’s hand — only a child’s hand would fit through the slit — appeared above and grabbed hold of the cup.

People, not livestock! People in the stock cars, even though this was contrary to the transportation regulations! What a mess. You just didn’t do that sort of thing at the Reichsbahn. He went back to his station house to try to get some information about where the train was heading. Theresienstadt. The name meant nothing to him. A small place a few kilometers north of Bauschowitz, last station at the border of the protectorate. He went back out again to have another look at the cars, but two sentries in black uniforms came hustling toward him, machine pistols at the ready: SS. Grandfather turned around and walked quickly back. A gruff call followed him threateningly.

It’s war, he thought, peeking out of the steamed windows of the overheated station house a short while later. With trembling fingers, he buttered himself a piece of onion bread. Must have been prisoners of war, Russians. But he knew this wasn’t true. The train had come from the west. The hand was a child’s. He also knew he wasn’t going to do anything. “I was scared of the SS.”

He told me this in the sun-flooded garden of his yellow house, and even though I loved him, because he was my grandfather, whom I’d only ever called just Pa, I hated him and he could feel it. We began to play the board game.

Then something strange happened. In the middle of the game his hands started to tremble, and he gazed into the distance so as not to have to look me in the eye. His voice sounded frail: “I thought back then that if anyone ever found out what we’d done to the Jews, it would be horrible for us.”

I stared at him, unable to speak a word. My grandmother sat at the table and just watched us. At that point I didn’t yet know she had Alzheimer’s. My grandfather stood up without saying a word and went inside the House of the Morning Sun.

A few minutes later he reemerged and handed me a padded envelope. I opened it and emptied its contents onto the game board. It was his Party membership book, with lots of colorful stamps with the Reich eagle affixed in each month he’d paid his party dues: in mint green, pale red, light blue. There wasn’t a single one missing. There was also a Hakenkreuz stickpin lying there — his Party badge. My grandfather made a gesture of surrendering it all to me, a twelve-year-old, and said: “Please. Take it. I can’t have it in the house anymore.”

My grandfather suddenly seemed to be sitting very far away from me. The distance between us was overwhelming, even though I could have touched him with my hand. Everything was suddenly beyond reach: the garden around us, the apple trees behind our little table; the table itself seemed in another dimension, and I couldn’t move the game pieces anymore. My grandmother sat there like a statue, blurry on the left edge of my field of vision, my grandfather somewhere in front of me. I closed my eyes. Everything was silent. A stillness you could hear. At some point I opened my eyes, put everything back in the envelope, and took it.

2

It is not always cold in Berlin. There are summer days when the city glows and the hot, sandy soil of Brandenburg chafes between your toes. The sky floats so high that you feel its blue belongs to outer space. Then life becomes cosmic in this city where simultaneously so much happens and nothing at all. There were days like this in August 1942, when a handful of people were sailing on Wannsee for the last time in their lives, and there are days like this seventy-five years later, when I meet a man named Hans Coppi.

Hans himself is approaching seventy-five, though he seems younger. He’s slim and tall (like his father, who was known as “Stretch”), wears round glasses, and has an alert, ironic gaze. I don’t know exactly where this meeting will lead — I’m the author of a nonfiction book about the Nazi era, but I really want to write novels or make movies. But what Hans Coppi has promised is an authentic story, one that screams to be told in another nonfiction book.

Hans grew up as a sort of VIP in the eastern part of Berlin during the Cold War. This had to do with his parents, who posthumously came to be regarded as celebrities. They’d been in the resistance, so-called antifascist fighters. His mother had been permitted to give birth to him in a Nazi prison. Then it was off to the guillotine for her. Hans Coppi, a degreed historian, has spent his entire life trying to figure out what happened to his parents and why they, along with a group of friends who went sailing for the last time that summer of 1942, had to die so young.

I’d always thought I knew the most important Nazi resistance fighters: Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg with his bomb of July 20, 1944; Georg Elser, the manic lone wolf with the homemade explosive device that missed Hitler by just a few minutes in 1939; the upstanding and yet truculent Sophie Scholl and her morphine- and Pervitin-consuming brother, Hans. But according to Hans Coppi, there’s another story that belongs in this canon, one surrounding a couple with whom his parents were friendly: two people who fought the dictatorship longer than all the others and for whom this fight was also a battle for free love. Their names were Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen, and over the course of the years more than a hundred people assembled around them and formed an enigmatic network that consisted of nearly as many women as men, all of whom wanted to do something against a world where injustice had been made law. It’s a story of young people who wanted one thing above all others: to live — and to love — even if the era in which they came of age was steeped in death.

It’s not easy, what Hans Coppi has undertaken: to find out what really happened back then. Because when Hitler learned of the plot against him hatched right in the center of the capital of the Reich, he was so furious that he ordered all evidence of these remarkable activities erased, to falsify the records beyond recognition. To bury and obscure the truth about Harro and Libertas and all the others. And the dictator nearly succeeded.

I meet Hans Coppi at a café at Engelbecken, the intersection of East and West, where the urban parables of the old capital of East Germany rub up against the former city of West Berlin. Here, socialist high-rise blocks stand opposite ornate nineteenth-century apartment buildings. Here, Saint Michael Church, built by a student of the famous architect Schinkel, roofless since a bombardment in World War II, still projects toward the sky into which Hans Coppi squints skeptically on this hot summer afternoon, because he knows that in the early evening the accumulated heat will dissipate over this strange and sometimes so fraught city.

My young son has come along to the meeting. He’s barely a year and a half but is as big as a two-year-old. He finds our conversation less interesting than the ducks on the nearby pond. Every time a duck slips from its nest in the reeds into the water because the boy’s gotten too close, I get up and keep him from scurrying to the edge of the pond, bring him back to the table, and offer him a sip of his rhubarb juice. Perhaps it would have been better to have left him at home so I could focus entirely on the meeting. But Hans Coppi seems undisturbed by the interruptions. He watches us attentively.

When, two weeks after the arrest of Harro in September 1942, Hans’s parents were also arrested, he may have felt it in his mother’s belly. She was initially detained with other women at the police facility on Alexanderplatz and then, in late October — heavily pregnant — was transferred to the women’s prison on Barnim Strasse. There, at the end of November, she was allowed to give birth to her child and named him Hans, which was also her husband’s name.

Suddenly I cringe: I hear a clink and look over at my son. He’s taken a bite out of the juice glass sitting in front of him. It takes me a moment for it to fully register. But the missing half circle of glass is unambiguous. I carefully fish around in his mouth and remove a perfectly formed half moon of glass. Fortunately he isn’t hurt. I look at him, bewildered, and he looks back somewhat puzzled as well. I didn’t know that a little child could bite through a glass, particularly so cleanly, and he apparently also didn’t know it. Hans leans his head to the left: “The boy’s got a lot of energy.” And suddenly I realize why my son has come with me to this meeting, because now I hope that he, like Hans Coppi, will master life by grappling with history.

It’s hot in Berlin that afternoon, and after the conversation I head with my child to Wannsee, to swim and because there are more ducks there. And because the lake is closely associated with the events depicted here. It’s August 30, 2017, seventy-five years since Harro’s arrest. The wind kicks up and a storm blows in.

3

Searching for clues in Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood: Where the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or Reich Main Security Office, once stood, today there is a memorial site called Topography of Terror. Here were the headquarters of the Gestapo, the Nazis’ secret police. Here is where Himmler had his office, and did yoga for two hours every morning before setting about his daily murderous business. Eichmann engineered the genocide of the Jews here. And in the concrete basement, which housed a jail, Harro and then Libertas were imprisoned, as well as Hans Coppi’s father. Harro’s cell, number 2, is, like the others, no longer here. The building had been severely damaged in a Royal Air Force attack, the ruins torn down after the war. In the 1970s a demolition company was based here, while on a ringshaped racetrack you could zoom around without a driver’s license. Today, in what was once the basement, there’s an exhibition that also memorializes Harro Schulze-Boysen.

I meet Hans Coppi in front of the information placard in the open-air portion of the museum. He seems fragile on this day. He asks how my son is doing, and then we walk together along a canal-side street formerly known as Tirpitzufer toward Bendlerblock, the current German Defense Ministry on Stauffenberg Strasse. The German Resistance Memorial Center is housed there. In that solid building from the 1930s, a room on the fourth floor stores all that Hans Coppi has found in his decades of research, all he has carried there in order to illuminate the events surrounding Harro and Libertas and all the others. It’s a room full of letters, photo albums, files and notes, interviews with witnesses, diaries, interrogation transcripts.

As odd, dramatic, or improbable parts of the following series of events may sound, this is not a fictional account. I find it particularly important in this case, where the truth has been distorted many times, not to add another legend, but to report as accurately as possible, combining my skills as a storyteller with the responsibility of the historian. Everything in quotation marks is documented with a source. Still, this is not a scholarly book, and I have tried to occupy the hearts and minds of these characters in a way that a novelist is better equipped to do than an academic historian.

The location is Berlin, a city that has lived through many metamorphoses, filled with people who shared similar desires: people who liked to eat well, go to the movies or out dancing; who had families, raised children, or just wanted to be loved. People who met up in cafés even when figures in black uniforms were sitting at the next table. Dabs of color in a sea of gray and brown. People who wondered how to react to insupportable political situations: how to conduct themselves during times that demanded conformity. People who clearly distinguished themselves from my grandfather, who just kept his head down and performed his duties as an engineer for the German railroad.

— Norman Ohler, Berlin

PROLOGUE: THE THICK OF IT

Der Oberreichskriegsanwalt

Berlin, 18 January, 1943

St. P.L. (RKA) III 495/42

To:

Frigate Captain E. E. Schulze

Field Post Number 30 450

Concerning your request of 9 January, 1943, I hereby inform you that the aforementioned confiscation of assets does not only mean the confiscation of any valuables in possession of the convicted but also, as an additional punishment, that the remembrance of the convicted shall also be destroyed.

By order of

Oberstkriegsgerichtsrat d.Lw.

This letter from Dr. Manfred Roeder reached Erich Edgar Schulze three weeks after the execution of his son Harro.

1

The first of September, 1939, is a Friday. The sky is overcast. During the afternoon it is seventy-four degrees, though it gets cool toward the evening. It is a day when everyone in Berlin feels that something fundamental is changing. People hustle along Kurfürstendamm, nicknamed Ku’damm, the main boulevard of Berlin’s well-to-do city center, full of shops, department stores, and restaurants. It is rush hour: the cafés and bars are full, and excited chatter fills the air.

Sir Neville Henderson, the British ambassador, enters a pharmacy in the neighborhood of Mitte, and asks for codeine, an opiate, to calm his nerves. When the pharmacist asks for a prescription, Henderson alludes to his position with British humor: If the medicine poisons him, the pharmacist will no doubt receive a reward from Goebbels. Henderson is thus able to get the drug prescription-free, and walks back to the embassy more serenely.

At 6:55 p.m., the air raid sirens sound. Traffic grinds to a halt, cars honk and quickly turn in to side streets, pedestrians search for shelter. Word gets around: Polish aircraft are attacking Berlin. In reality, German Stuka dive bombers have entered the capital’s air space, accidentally causing the alarm. The all-clear is given at seven p.m., after five fearful minutes of screaming sirens. The war that Hitler has initiated with his invasion of Poland on this day has suddenly become real for Berliners.

Dusk starts around eight-thirty. Because of the blackout directed on this first day of war, night falls more quickly than usual. Kurfürstendamm, radiating brightly the evening before, is dark, the thousands of bulbs in the cinema marquees extinguished, the ads for the brand-new Wizard of Oz and the still running Clark Gable vehicle Too Hot to Handle invisible, the windows of department stores covered in cardboard.

A crowd has gathered in front of the grand Sarotti neon sign advertising chocolates. For years it has dependably burned bright, but now, ominously, it is out, no longer promising sweets. The giant neon Deinhard champagne bottle, from which artificial pearls of light normally bubbled, juts blackly into the sky as well, as if empty: the party is over. A bus with its headlights darkened shudders to a halt, its interior lights also turned off, making the passengers look like ghosts.

Nobody is shopping along the broad sidewalk. Some pedestrians have glow-in-the-dark patches on their chests the size of a button; others hold glowing cigarettes. Driving has suddenly become adventurous, particularly in the side streets, all the more so in the ones lined with trees.

On this, of all nights, the young German air force officer Harro Schulze-Boysen is celebrating his thirtieth birthday at the home of friends, a married couple named Engelsing. Herbert Engelsing also has a birthday, in his case his thirty-fifth, and they’ve decided to party together.

Harro’s friend Herbert is a producer and legal advisor for Tobis, one of the most important film production companies in Germany. Sponsored by Goebbels, he has excellent political connections, without ever having to renounce his humanistic ethos. His position in the movie business is so influential that despite the Nuremberg Race Laws, after much back-andforth and with Hitler personally intervening on his behalf, he was even permitted to marry his great love, Ingeborg Kohler, who is deemed “half Jewish.”

The Engelsings’ villa in Grunewald, in this poshest neighborhood west of Ku’damm, is one of the few places in Berlin where one can speak freely and where the type of socializing cultivated seems to ignore the very existence of the dictatorship. The Engelsings’ circle of friends includes famous actors like Heinz Rühmann and Theo Lingen; the writer Adam Kuckhoff and his wife, Greta; as well as the dentist Helmut Himpel, whose skills are so widely renowned that German film stars make pilgrimages to his practice, and who still secretly treats his Jewish patrons — who can no longer be seen entering his office — privately at his home, for free.

Ingeborg Engelsing is a slender, gamine woman who loves to play hostess. She stands in the door of the two-story house at Bettinastrasse 2B in Grunewald, her hair tousled, her smile charming. She is only twenty-two years old, thirteen years younger than her husband. Initially Inge and Enke, as her spouse’s nickname goes, had considered canceling the party with Harro because of the start of the war. Then Inge decided: “Now more than ever!”

It’s twenty past nine, and in the British embassy, unlike in most of the rest of Berlin, the lights burn brightly, like a flame of reason denying the darkness of ignorance. Sir Neville Henderson, by now likely flush with codeine, sends a message to Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister, conveying London’s demand that all Wehrmacht forces be immediately withdrawn from Poland. France follows with the same note half an hour later, at 9:50 p.m. No ultimatum is issued, and the word war is still avoided. Both of the Western powers have, however, begun to mobilize.

In the villa in Grunewald, Harro’s wife, Libertas Schulze-Boysen, reaches for the accordion. She wants to play to express her contradictory feelings: on the one hand, her hope that this momentous shift — to a shooting war — will spell the end of the Nazi menace, and on the other, her fear of what all could happen before then. She boisterously plays “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem, and everyone sings along. Next comes “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” so beloved among the British military — a greeting to friends in England, the global power whose decisive intervention everyone at the party now counts on. Then she belts out the Polish national song. Most of those in the room don’t know the words, but Harro sings ardently along:

Poland is not yet lost

As long as we’re alive

The chorus is so loud that Inge Engelsing steps outside the house, worried, to make sure the neighbors can’t hear it. But the heavy velvet curtains in front of the windows sufficiently muffle the sound.

At some point in the wee hours of the morning, when the party is starting to fade, a small group gathers around Libertas. The gramophone is playing, and there is a question on everyone’s mind: Will the so-called Thousand-Year Reich last only until the end of 1939, or will it manage to hold on into 1940?

Harro joins the circle. His chin trembles with hate when he speaks about the Nazis. Unlike most of the other guests, he doesn’t believe the regime will implode so quickly. It’s delusional to think the end is just around the corner and that the first air strikes on Berlin could come at any moment. Because of his job at the Luftwaffe, he knows the Royal Air Force is in no condition to strike and that the British need time to build up militarily. “I don’t wish to destroy the hope that petty bourgeois Hitler is facing an inescapable catastrophe,” he explains, “but it’s not that simple.” Initially, the dictatorship will in fact get stronger, he argues. Poland has no chance; it will go down quickly — child’s play for the German war machine. France, too, represents no problem for the Wehrmacht, in Harro’s view: the country has no fighting spirit. Then will come the attempt to capture England. Here, success is questionable — but in any case, the western European powers alone won’t be able to defeat Germany.

Russia will get entangled in the war, Harro predicts. But it will take the United States to assure a final victory. It will be a long time before the Western powers are capable of a counterstrike, and in the meantime the dictatorship will become ever more violent and unhinged.

With his lively blue eyes, Harro looks around, from one friend to the next, his lips pressed together tensely. In earlier times Inge Engelsing had considered him “too handsome and inconsequential.” She’s revised her opinion, however, and now sees in his striking features a luminous quality, something defiant and beautiful when he defends his ideas in such a fiery manner. Everyone gapes at him and his prophetic words, and suddenly Harro realizes what a peculiar figure he cuts, in his military uniform at his own birthday party in the somewhat helpless company of liberal spirits for whom mere lip service is already seen as a risk.

Dawn breaks as he asks Libertas for one last dance. The two of them swing together, and they do it well, as always. Everyone in the room marvels at them. Nobody knows the risks they are willing to take in order to stop the insanity of the Nazi war machine that’s been unleashed that very day.

PART I

ADVERSARIES

(1932–33)

No one could risk more than his life.

— HANS FALLADA

It was an attempt to join together in overcoming all the old antagonisms. We were known as “adversaries.”

— HARRO SCHULZE-BOYSEN

1

In the fall of 1932, democracy still rules in Germany. There’s unrest at the university — a brownshirt has hung swastika banners from the student memorial wreath and a leftist has cut them down. Now the two enemy camps stand in front of the main building of Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University filled with hate, separated only by a narrow gap, “ready at any moment to go at each other if a word of provocation comes from either side,” as a college friend of Harro’s recalled.

On one side, the red students gather, the socialists and communists and a sprinkling of social democrats. From the right, the Nazis and members of the allied nationalist students’ corps scream their battle slogans decrying “Judah” and “the system.” The university has been frequently paralyzed by political protests during the insecure Weimar Republic. This time, too, the president of the university wrings his hands helplessly, appealing in vain to both sides.

Harro Schulze-Boysen is a young political science student, and on this day he’s slept in at the so-called Red-Gray Garrison. One of the first communal living arrangements in Germany, it is an eight-room apartment on Ritter Strasse in the central Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg. There is no furniture, and everything is shared — cleaning, cooking, money.

Alongside Harro is Regine, a slim young fashion designer from a formerly wealthy family. Wearing nothing but lipstick, she swishes the strawberry blond hair out of her face — and suddenly says something so shocking, so in love as she is, that Harro gets up, throws on his trademark blue sweater, and shuffles into the kitchen to look for something edible. He finds nothing but two dry bread rolls, but it doesn’t matter — at least there’s a nice cup of tea.

Does he want to have a baby . . . ? Is Regine harboring bourgeois dreams?

Harro is twenty-three and wants to radically alter society. Along with his best friend, Henry Erlanger, and others in their circle, he is serving the future of not one child, but many — the children of all of Europe, of the whole world. There’s enough to do, especially during the current devastating worldwide crisis: soup kitchens all over the place, bank failures, unpayable rents, six million unemployed in Germany alone, depression and helplessness across all classes, the imminent fall into the abyss always looming. An entirely new society is necessary; the situation is polarized. Parties like the Social Democrats or the German Center Party no longer seem to represent the people. But what is supposed to replace them? And just what is the people, anyway?

The thoughts in Harro’s young mind are far too complex to offer up simple solutions. His goal is still too diffuse, and he’s even intrigued by right-wing positions, supporting, for instance, the battle against the Versailles Treaty, which saddled Germany with expensive reparations after the country lost the Great War. Such thoughts, anti-parliamentarian impulses, pervade his thinking, all of it still half baked.

How are you supposed to responsibly raise a child when there are so many fundamental questions to settle? How can Regine not understand this? Harro looks down the hall into the large room where she’s lying on a mattress seductively. But he has to go. Off to university.

The streetcar is jammed, kids scurrying around, the smell of sweat and tobacco in the air, ads on the varnished pale wood doors: kakadu — THE BEST BAR ON KURFÜRSTENDAMM. A drunk leans against a window, dozing; a haggard woman of about fifty stares brazenly at the tall, blond Harro with his athletic build and gleaming blue eyes. Horse carriages, hackneys, freight trucks. vote social democrat! A line in front of the unemployment office, the people surprisingly well dressed, different from the morphinists on a bench, with their deep, dark eye sockets and sickly bodies, still addicted from the war, when opiates were dished out liberally to wounded soldiers.

“Europe was the clock of the world. It’s stopped,” Harro had written in the most recent Gegner, the publication he works for: “The gears of the clock are beginning to rust. One factory gate after the next is closing.” Everywhere, economic processes that grant power to cartels are surging. Capitalism must be banished! thinks Harro. But communism doesn’t lead to anything good either: just a rigid apparatus, slaves to Moscow. COME TO SOVIET RUSSIA! screams another ad: CHEAP EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL FOR DOCTORS, TEACHERS, WORKERS.

“I’ll say it again, I’m not a communist.” That’s what he told his worried mother, Marie Luise, who runs a bourgeois household in Mülheim, a city far west of Berlin, near Germany’s Dutch border. “The communist party is a form of expression of the global socialist movement,” Harro had written in a letter to her, “the Bolshevik Party being typically Russian. Hence not suitable for Germany.”

On the streetcar winding through Berlin, Harro looks out on a tumultuous city — one rife with what he calls “big city disease.” The neighborhood of Friedrichshain, for example, is known as the Chicago of Berlin because of its gangsters. It’s a confounding, unsettled time — one ripe for experimentation.

Harro steps out of the tram close to Alexanderplatz, where the road is being redone. Workers are ripping up the old cobblestones as if tearing scabs off wounds, then pouring hot asphalt into the hole. The ground shudders as a U-Bahn rumbles underground. The leaves are already brown on the trees, and it’s getting cold. Striding easily, with his hands in his pants pockets, he nears the plaza in front of the university, where beggars are sitting at small tables in front of the university’s gates. Suddenly he sees the standoff between the groups of students — leftists versus right-wingers — and he realizes immediately that the situation calls for decisive intervention on his part. Harro knows the crowd, and they all know him and his blue sweater. He enjoys the trust of students from across the political spectrum — because he debates things so effectively, but also because he stands out. He has a rare quality that is all the more noticeable at a time of chaos: charisma.

As the desire to fight is rising in those on both sides, he retains his amiable and upbeat equanimity: he greets one brownshirt after the next with a handshake, asking what’s going on, listening placidly to the saga of the removed swastika banner. No, he’s no friend of the Nazis — he thinks they’re dullards and rejects their anti-Semitism outright — but he’s still able to talk to them. Next he wanders over to the other side, where they’re loudly singing “The Internationale,” and shakes hands there, as well. It’s the side that appeals to him personally: he reads Karl Marx and he can damn well distinguish between an internationally oriented ambition for a just social order in which everyone has access to education, living space, health care, and the extreme right wing, the anti-Semitic affectations of the Nazis, with their goal of division and discrimination.

After a while, the rallying cries on both sides begin to subside. Everyone looks at him, including the university president, and like any instinctive revolutionary, Harro seizes the moment, continuing to shake hands, going back and forth between the two sides now, managing to defuse the conflict.

2

Things with Regine are moving along briskly. Together the occupants of the communal apartment are a merry bunch: artists, gays, gay artists, revolutionaries, bohemians. They’re all young and attractive and lead erratic lives in this erratic Weimar era. For Harro, the most important thing isn’t love, but politics, just as it has always been. He is, as a friend says of him, an “ardent German,” with a “very deep German cultural awareness, artistic and philosophical, possibly innate, inherited from his family but also acquired.”

Harro’s most renowned relative is a brother of his paternal grandmother, the grand admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who’d built the ocean fleet for Kaiser Wilhelm so Germany could hold its own in a war with Great Britain. Into his old age, Tirpitz sported a two-pronged beard that impressed the grandchildren with its pair of martial-looking wedges protruding downward. Uncle Tirpitz is the battleship of the family and the great model for the adolescent Harro. He wants to do just as much for “the German cause” as Tirpitz, and “champion the country, consciously working toward its improvement,” as he says in a letter to the legendary great-uncle.

Harro’s father, Erich Edgar, who also served in the navy, is involved, like Tirpitz, with the right-wing German National People’s Party. With his intellectual leanings he could have been a scientist, perhaps even an artist, but Erich Edgar, known as E.E. for short, with his strong sense of duty, exemplifies the Prussian work ethic. He’s a father who tells his son not only that he can cry, but that he should, in order to show that he indeed has feelings, but just one tear, please, then immediate composure before a second one falls. Harro’s mother, Marie Luise, is less disciplined, but spirited: a tenacious, assertive person of small stature and sometimes great excitability, a lively, romantic woman who always has a decisive opinion, sometimes speaks before she thinks, and as a result often leaves dumbstruck her cool-headed husband, who is reserved even in bed, as she later in life complained to her grandchildren.

Harro has a perfect political sparring partner in his father, a professorial figure with a huge collection of books who often sits upright at his mahogany desk, reading by candlelight for hours at a time, almost otherworldly in his rigor. Erich Edgar’s goal is to raise a free-thinking conservative. But increasingly over time Harro overtakes his father in his skills at argumentation, because his mother’s hot blood also flows in him, and passion is as much a part of politics as rationality.

The vehicle for Harro’s engagement, the Gegner, has in 1932 developed a new concept under his direction: to change from a static publication to a bona fide movement. Toward this end he set up what were called Gegner meetings, where authors and readers enter into dialogue: “public contradictory debate nights,” as one of the flyers puts it. Harro writes confidently to his parents about the approach: “There’s not a newspaper in Germany that manages to zero in on people who have something to say in such an autonomous way.”

Developing visions beyond party boundaries, transcending conventions, and testing novel arguments appeals to many. Young people looking for answers to the burning questions eating at everyone take part in the evening Gegner gatherings at Café Adler on Dönhoffplatz. The meetings quickly become so popular that they are taken beyond Berlin and staged in other German cities as well. “There’s extraordinary discipline and a strange camaraderie between left and right,” reports a participant, indicating how unusual such behavior is among overheated twenty-somethings: “Young people who would immediately start throwing punches at each other on the street instead listened to arguments, united in the collective rejection of the boastful, doctrinaire party bigwigs.”

Even if the way forward is still unclear, Harro attributes the Gegner movement to a rebellious moment, and speaks of an “invisible alliance that numbers in the thousands, who might still be distributed around in various other camps but who know that the day is approaching when they’ll all need to come together.” Harro wants to reconcile the society that is threatening to split apart — just as he had at the university. “A people divided by hate . . . cannot get up again,” he writes in the Gegner — a twist on the words of Abraham Lincoln: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” It’s no easy task that Harro takes on in this late phase of the Weimar Republic.

3

There are manic days and nights that fall of 1932, the last months of freedom, one of the most inspired periods in all of German history, with Berlin possibly the most intellectually vibrant city in the world. One literary circle feeds into the next, and Harro’s best friend, the slender, dark-haired Henry Erlanger, drags him around everywhere. “The crust is suddenly broken, as the old powers, those of the Weimar system, are finally beginning to stand down” is how a friend of Harro’s describes the equally precarious and exciting situation: “Suddenly heads everywhere were emerging above the fog clouds of jargon and starting to speak in a language that was in a new sense shared . . . It was intoxicating.”

This rush-inducing discourse comes to fruition, among other places, in the editorial offices of independent publications such as Carl von Ossietzky’s Weltbühne, where Kurt Tucholsky, one of the most prominent political authors of the Weimar Republic, writes, or Harro Schulze-Boysen’s Gegner, housed in a sparsely furnished attic room with a view of Potsdamer Platz. From the hall, visitors enter directly into the first of the two long, narrow rooms, the second filled with books from German philosophers, a typewriter, a seating area, a fold-up cot. Harro often stays overnight here because it’s convenient just to sleep at the office, where there’s always something to do: editing text, speaking to new writers, preparing contracts — plus in the evening the theater is nearby, putting on things like Brecht’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, a “fairly crazy piece, music definitely good,” as Harro describes it to his parents.

It’s a fulfilling, exciting existence — despite or perhaps because of the unsure future. “Every person feels inspired by the voice of God at some point,” Harro rhapsodizes in a letter from the Gegner period: “And you can supplant this arrogant word through knowledge, need, or desire; but it remains the same.” The mission, perhaps seemingly pretentious, but bitterly necessary: saving the world from impending ruin. Because while “the discussions between fish and roast, over tea and whisky continue blithely along, outside the SA is marching steadily forward with firm steps.”

There’s a photo of Harro from this time over which his mother regularly frets: his facial features are more striking than usual, and his beautiful blue eyes look possessed — and that’s what he is as he races from one event to the next in his light coat, colorful shirt, tousled hair, feeling “never more alive.” He tirelessly writes and makes connections, and then also becomes the publisher of the Gegner, now pouring every penny he gets from his parents into the magazine, on top of all his time. If there aren’t enough paperboys he throws a bag over his shoulder and stands in front of the university or technical college selling copies by hand, newsboy cap on his head. “The Gegner is gaining genuine renown,” he reports home to Mülheim: The print run has risen to over five thousand copies, and with the publication of the October 1932 issue comes a hundred new subscribers. November 1932 begins chaotically. A strike breaks out among public transport workers: no S-Bahns or U-Bahns run, no buses, no streetcars. During the resultant conflicts with the police, three people are killed. Shortly thereafter, in the national elections on November 6, the share of the vote won by the Nazi Party (NSDAP) drops for the first time, 4.6 percent to be exact, while the German Communist Party (KPD) jumps by 2.6 percent. Panic breaks out in the Hitler camp. “The year 1932 was a streak of singularly bad luck,” writes Goebbels in his diary: “It must be shattered in pieces. The future is dark and murky; all prospects utterly vanished.”

But Harro senses that behind the curtains, capital is working tirelessly for a Nazi power grab. He follows with suspense the government declaration by Kurt von Schleicher of December 15, 1932, in which the Reich chancellor rejects not only socialism but also capitalism. Will industrialists come to regard von Schleicher as an unreliable waffler as a result? Hitler on the other hand has been cultivating the kings of industry for years. In January 1932 he’d made clear in a speech in front of the influential Düsseldorf Industry Club that the “socialist” element in the NSDAP program was merely a way to pick up votes among the working class and lower middle class. In no way did it reflect a desire to reduce the political influence of businessmen. Moreover, it’s clear that the Nazi rearmament plan holds out the prospects of massive contracts for German manufacturers. Since the speech, contributions to the party have been flowing generously.

4

Industrial leaders aren’t the only ones Hitler is cultivating. The Nazi leader from the small Austrian town of Braunau has also become the great hope of major landowners. Fifty kilometers north of Berlin, on the morning of January 30, 1933, the nineteen-year-old Libertas Haas-Heye awakes and looks out the window of her chambers at the forecourt of Schloss Liebenberg, her family’s ancestral home. The snow that covers everything — the manor house, the farmhouse, the fieldstone church — glistens in the morning sun. The fountain, a gift from Kaiser Wilhelm, a close friend of her grandfather’s, is also coated in gleaming white. Libertas gets up, pulls her nightgown over her head, and throws it into an open wardrobe.

It’s a special day. The local Liebenberg branch of the SA is to set off for Berlin, because today it is actually about to happen: Hitler will be appointed chancellor of the Reich. Libertas’s uncle, Fürst Friedrich-Wend zu Eulenburg und Hertefeld, the titled head of Schloss Liebenberg, wants to witness this historic moment, and has asked Libertas if she’d like to accompany the group.

But before they’re supposed to leave, Libertas first saddles her horse. It’s named Scherzo, referring to a type of musical composition, because the horse is always moving in rhythm and is maniacally agile. Just like its owner — at least most of the time.

There’s a melancholy note to Libertas as well. Ever since she can remember, her parents have only sporadically looked after her and her older brother, Johannes. Ten years prior they’d divorced: her father, Otto Haas-Heye, is a prominent fashion designer, art professor, and bon vivant, at home in all the metropoles of Europe; her mother, Tora, on the other hand, finds the fashion world “horrible,” is weak of nerve, and shields herself from the somewhat too-real world, preferring to hole up at Schloss Liebenberg. For a while a governess had looked after Libertas; later the Jewish artist Valerie Wolffenstein, a co-worker of her father’s, had taken over supervision of her. The time with Valerie had been pleasant, but had not lasted. Libertas had lived in a Berlin boarding school, then in Paris, London, and Switzerland, always ready to leave again almost as soon as she settled in someplace, ready to get accustomed to yet another strange city: to make new contacts, win new sympathies, prove herself and orient herself anew. Over time she’s developed techniques to appeal to others. Libs comes across as open and fun-loving, and charms people with her cheerful demeanor; she can sing well and plays the accordion captivatingly, with knowledge of thousands of songs.

Her ride through the Liebenberg Forest, with the clopping beat of Scherzo’s hooves muted by the snow, is an absolute joy. It’s an ice-cold day, this January 30, but beautiful, with a clear blue sky visible through the white-powdered branches of the tall trees that fill the estate. Libertas knows every tree along the way to Lankesee, their private lake. “O, you, my Liebenberg, where the green boughs of the weeping willows toward the heavenly pond bow.” She’d come up with that poem at fourteen, inspired by Rilke.

There is an artistic tradition at Liebenberg. Her mother loves to perform, above all else, the “Rosenlieder,” the “rose songs” known all over Europe and written by her own father, Fürst Philipp of Eulenburg, Libs’s grandpa, whom she loved deeply. He’d also written “Fairytale of Freedom,” in which a character named Libertas pops up, the embodiment of individual freedom, after whom Libertas was named. The Fürst died in 1921, more than eleven years prior, but she still remembers him well.

Grandpa Philipp wasn’t just another person. Earlier, in a long-before faded and yet still very present era, he’d been the most intimate friend and closest advisor to the Kaiser. But there’d been a scandal surrounding the friendship, the biggest of the Wilhelmine era and the first homosexual scandal of the twentieth century, covered in the press worldwide.

In 1906, a shocked public read in a series of articles by Maximilian Harden in the newspaper Zukunft, or Future, that the Kaiser tarried too long at Liebenberg palace, and not because the deer hunting alone was so scintillating. There was talk of a Round Table that secretly determined the policies of the empire, and which indulged in occult sessions — and in gay activities. Fürst Philipp von Eulenburg, it was said, ran proceedings in a negligee.

The sweetheart of Libertas’s grandfather: Kaiser Wilhelm II, depicted here in a French caricature.

One sensation after the next shook the prudish, so-called Iron Age of Prussia. Berlin, where life was supposedly strictly regimented, quickly surpassed Paris, Rome, or London in terms of disreputability. Suddenly the former “Sparta on the Spree” became the new Babylon, and the posited moral superiority of the Prussians evaporated. The entire world now sneered at Berlin’s sexually charged subculture — or marveled at it, or even traveled there to mingle in it: a self-fulfilling prophecy. “That’s chaste Germany for you!” read a headline in the French newspaper Figaro.

The scandal stained not only Berlin’s sterling reputation, but also the honor of Libertas’s once distinguished family. When in April 1908 a fisherman from Lake Starnberg attested during a subsequent trial that he’d had sex in his barge with Eulenburg, Fürst Philipp was arrested. He denied the charges anew — and was then accused of perjury. Wearing dark sunglasses in order to remain anonymous, he had to take the train into Berlin again and again for doctor’s appointments and to appear before judges. Occasionally, whether because he’d really been so affected or for strategic reasons, the once vital man was even carried into court on a stretcher.

In order to save his own neck, Kaiser Wilhelm had distanced himself from Eulenburg, his best friend. He had stopped visiting Schloss Liebenberg and surrounded himself with new advisors who seemed diametrically opposed to the peace-craving of the now discredited Liebenberg Round Table. On a warm day in June 1908, the case against Eulenburg was adjourned due to his lack of fitness to stand trial, and never taken up again. The suspicion of homosexuality could be neither confirmed nor cleared. While this meant the Fürst was not legally convicted, he did suffer personal and societal condemnation — a stain on his reputation that he was unable to erase during his lifetime. Reclusive, with hardly any visitors, he lived at his palace until his death in 1921 and looked after his grandchildren, including Libertas. The aging aristocrat told them stories of summer trips with the Kaiser on the yacht Hohenzollern in the fjords of Norway, where they hunted whales. His former best friend, the Kaiser, the only one who could have rehabilitated his reputation, never got in touch again, not even while in exile at Castle Doorn, in Holland, after losing the First World War.

5

On Wednesday, January 30, 1933, as Libertas is preparing to depart for Berlin, Harro is in the city phoning a fellow Gegner writer, Adrian Turel: “Hitler is chancellor! Take the underground to Potsdamer Platz and have a look at the festivities. Then maybe you can stop by the office. Nothing’ll happen to us right away.”

Turel covers his typewriter, hops on the train, rides to the center of town, and walks down the median of the grand boulevard Unter den Linden. In the road on both sides of him, massive columns of SA stream past with torches in their hands for the procession later, stepping lively, like gladiators striding into the arena. “I was going against the stream. And then I see: coming toward me were a Jewish industrialist and his wife, people I knew well. I greeted them happily as Jewish comrades, in the middle of the military-style columns of SA people . . . and said: ‘For goodness sake, trouble’s brewing! Get out of here!’ At which the woman smiled and said to me with childlike naivete: ‘But my dear Turel, don’t be hysterical! It’s just a Volks festival.’ ”

6

In the icy cold, several cars drive to the train station in Löwenberg, not far from Liebenberg. In one of them sits Libertas, and next to her, her uncle Wend, who is fifty-one, a man with a grin like a stripe across his face and what little hair he has on his head slicked back. Libs knows how much this day means to him: the Nazis are taking over in Berlin. Wend is smitten with this Hitler fellow. Two years prior he’d had an audience with him, and the man from Braunau was reassuring: “I’ll lead the battle against Marxism . . . until the total and definitive annihilation and eradication of this plague . . . I’ll fight to that goal ruthlessly, with no mercy.” That suited the estate owner, because in Liebenberg, too, people had demanded the breakup of the manorial land held by the one great local landholder, namely the Fürst.

In order to support the Nazi Party, Wend had sent a Hitler-approved circular to his friends among the landed gentry and large landholders, urgently recommending they all read Mein Kampf, which he said contained “an abundance of brilliant ideas.” Wend had set aside his initial misgivings about Hitler’s possible socialist tendencies: “If we don’t want Bolshevism, we have no other choice than to join the party that despite a few socialist ideas is the polar opposite of Marxism and Bolshevism.” Not only does he believe that the NSDAP can best solve the country’s problems, but he’s also convinced that “without Hitler, no form of government is possible in the long run.” And weren’t the Nazis predestined to rehabilitate his father, Fürst Philipp, since Maximilian Harden, the writer who triggered the Eulenburg scandal, was a Jew?

But what does Libertas think of the powerful new movement? Is she as enthusiastic as her uncle? On that day, after a one-hour train ride, they take part in the torchlight procession, and Libertas enjoys it. On the other hand, she knows little of Hitler’s goals, and isn’t terribly interested in them, as she lives from the heart and the gut. These are the places from which she hopes to write her poetry. Of course, Nazi propaganda is meant to appeal to exactly these same places, places beyond the level of rationality. When the Liebenberg group disembarks the train at Lehrter Bahnhof and heads toward the Brandenburg Gate along with the excited masses, Libertas is for that reason also moved.

Though politics may not be her cup of tea, Libertas, too, seeks to follow the suddenly powerful movement, and in March 1933 joins the local Liebenberg chapter of the Party with the member number 1 551 344.