Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

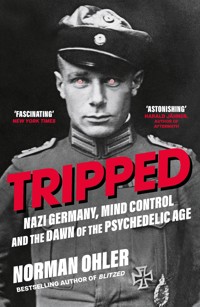

AS FEATURED ON THE JOE ROGAN EXPERIENCE 'Entertaining' The Times 'Utterly fascinating and illuminating' Sinclair McKay 'Fascinating... An astonishing read, with remarkably vivid protagonists' Harald Jähner 'Ohler weaves a masterful tapestry of history in this revealing and fresh account' David de Jong Berlin, 1945. Following the fall of the Third Reich, drug use - long kept under control by the Nazis' strict anti-drug laws - is rampant throughout the city. In the American sector, Arthur J. Giuliani of the nascent Federal Bureau of Narcotics is tasked with learning about the Nazis' drug policies and bringing home anything that might prove 'useful'. Five years later, Harvard professor Dr Henry Beecher begins work with the US government to uncover the research behind the Nazis' psychedelics programme. Originally created for medical purposes by Dr Albert Hofmann, the Nazis coopted LSD to experiment with mind control and find a 'truth serum' - research that the US, particularly the CIA, is desperate to acquire. Based on extensive archival research, Tripped is a wild, unconventional post-war history, a spiritual sequel to Norman Ohler's bestselling Blitzed. Revealing the hidden connections between the Nazis and the CIA's notorious brainwashing experimentation programme, MKUltra, Ohler shares how this secret history held back the therapeutic research of psychedelic drugs for decades as the West sought to turn LSD into a weapon.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 342

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Norman Ohler

Th e Infiltrators: Th e Lovers Who Led Germany’s Resistance Against the Nazis

Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany

Published by arrangement with Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, New York.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Norman Ohler, 2024

Translation copyright © Marshall Yarbrough, 2024

The moral right of Norman Ohler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. Th e publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 359 1

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my parents

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART I : MEDICINE

1. The Zone

2. From Paint to Medicine

3. At the Zurich Train Station

4. On Location: Novartis Company Archive

5. The Mice Don’t Notice a Thing

6. Swiss Cheese and Ergot

7. Agrochemistry

8. LSD in the Archive

9. Arthur Stoll’s Art

10. The Other Richard

11. Brainwashing

PART II : WEAPON

12. The Trip Chamber

13. Alsos

14. The Missing Box

15. Advisor Kuhn

16. Pork Chops

17. LSD in America

18. Brain Warfare

19. CEO and CIA

20. The Case of Frank Olson

21. Menticide

22. Operation Midnight Climax

PART III : NARCOTIC

23. Mösch-Rümms

24. Bulk Order

25. LSDJFK

26. The Revolt of the Guinea Pigs

27. The Bear

28. Elvis Meets Nixon

29. A Case of Wine

30. Light Vader Hofmann

Epilogue: LSD for Mom

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Image Credits

Index

INTRODUCTION

IN THE LATE 1990S, INSIDE A FORMER NUCLEAR MISSILE silo in Kansas, Leonard Pickard set up what was probably the biggest LSD lab of all time. The choice of this site for such a large-scale operation seems symbolic, given that the history of the powerful substance is tightly interwoven with that of the Cold War and its arms race. On twenty-eight acres of land, behind electronically controlled gates and a hundred-ton steel door that could withstand even a nuclear attack, Pickard was alleged to have produced a kilogram of the drug per month—due to its potency, an unimaginably large amount. With it, the graduate of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government was said to have provided 95 percent of the world’s supply of LSD.

On November 7, 2000, the day of the presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore, Pickard was inspecting the facility when he noticed that his gray Zen robe, which normally would have been carefully folded and put away, had been left carelessly in a corner.* Quickly snatching up the garment, Pickard and his partner decided to clear out of there. Though they were careful to stay under the speed limit, they soon saw flashing lights behind them. “This is it,” Pickard radioed to his buddy, who was behind him driving the truck with the lab equipment. Pickard didn’t obey the order to pull over and was pursued by officers with sirens blaring. All the while the acid chemist could think of only one thing: his wife, a Ukrainian student at UC Berkley, was nine months pregnant and would be giving birth to their daughter any day now.

When he reached a residential neighborhood, the fifty-five-yearold pulled his silver Buick over to the side of the road, pushed open the passenger door, scrambled over the seat, and leapt out of the car. An experienced long-distance runner, he shook off his pursuers and after a few miles crossed the ice-cold Big Blue River, a tributary of the Kansas River, to mask his scent from the search dogs.

In the moonlight, Pickard followed a set of train tracks, which led him to a small town with the big name of Manhattan, Kansas. Unsure whether he should try to blend in among other people or flee into the woods, he chose the latter. In the distance he heard helicopters, which searched for him with infrared scanners all through the night. He hid for hours in a concrete pipe that masked his body heat from detection, and in the morning, frozen to the bone, found a solitary farm and sought refuge in a truck parked out in the barn. At around seven o’clock the farmer’s dog found him there and alerted its master with its barking. Pickard asked the man to give him a ride into town, and the farmer agreed to do so. But this was only for show: while watching television at breakfast he had seen a wanted photo of Leonard Pickard. Soon a sheriff’s car was speeding their way. Again Pickard fled, running across open farmland. The police car followed him over the grain stubble, swerving as it drew ever closer to him. Finally the cop leapt out with weapon drawn and placed him under arrest. The first thing he did was to pull off Pickard’s wedding ring. Two life sentences without the possibility of parole, the verdict later read.

Leonard Pickard had never raised a hand against another. He hadn’t stolen anything or harassed anyone. All he’d done was manufacture a substance that half a century earlier had been considered the most promising pharmaceutical development of all time, a quality product made by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz. But in the years since then something had happened with LSD. It had been knocked off course, had been misunderstood and misused, and had fallen into the disreputable category of prohibited drugs that a United States official named Harry J. Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, had created almost singlehandedly after the Second World War. Over the years friends and supporters spoke out in support of Pickard, and in the depths of the coronavirus pandemic the unexpected occurred: a judge granted a “compassionate release,” and just like that, after more than twenty years behind bars, he found himself a free man.

Leonard Pickard’s unexpected release can be seen as symbolic of a broader reversal within society with regard to the treatment of LSD. Pickard, who was once judged so dangerous that the law wanted him locked away in a high-security prison for the rest of his life, now serves as a scientific advisor to a fund that targets opportunities at the intersection of psychedelics and technology, hoping to identify the pharmaceutical giants of tomorrow. He also advises international corporations and universities on the development of psychedelic medicines. Every morning from six to nine he studies the latest publications coming out of research institutions around the globe.

The early history of LSD would always have been fascinating, but in the current moment it seems especially relevant. A specter looms over the world: the specter of legalization. More and more governments are beginning to rely on scientific knowledge rather than bow to the ideological demands of the Cold War.

I myself became curious about the drug when my father, a retired judge, started to consider giving microdoses of LSD to my mother to treat her Alzheimer’s disease. He had asked me why, if the drug was actually supposed to help, he couldn’t just get it at the pharmacy. This launched me on my research.

The more I dug into the history, the more fascinated I became. I began to see how much of the early history of LSD was shaped by the shadow that lies over the molecule, a result of the personal connection between a Swiss pharmaceutical CEO named Arthur Stoll, a kind of unwilling forefather of psychedelics, and Richard Kuhn, the leading biochemist for the Third Reich. This relationship aided the National Socialists, who were beginning to study the use of psychedelics as potential “truth drugs”—questionable research, which, after the war, sparked the interest of the US military and its intelligence agencies in these substances.

This book is what emerged from my curiosity. In this moment when, after many decades, we are finally reconsidering the nature of our laws surrounding psychedelics, it feels more important than ever to look backward and understand how we arrived at those regulations in the first place.

The fact that the US government was introduced to LSD through Nazi research shaped much of the federal government’s early attitudes around it and other psychedelics; once the Nazis elicited a potential weaponized use for LSD, the drug was never able to shake that taint. An entire class of medicines with the potential to help treat diseases that otherwise are essentially incurable was caught between the collapsing Nazi regime and the early stirrings of the Cold War and saw its early promise shattered.

In addition to LSD’s militarized misconception from the Nazis, there were other areas of US drug policy influenced by the Third Reich. In fact, the eventual prohibition of all drugs, including psychedelics, can be traced back to Hitler’s Germany, where the Nazi approach to banning drugs, their so-called Rauschgiftbekämpfung or fight against narcotics, the forerunner to the War on Drugs, also inspired US prohibition policy. Indeed it was a US narcotics control officer named Arthur Giuliani from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, stationed in occupied Berlin after the fall of the Nazi regime, who imported much of the racist anti-drug policies back to the US. He would later reemerge to play a role in LSD’s early history in America as well.

When people think of LSD, they don’t think of the Nazis, and yet that unseen hand played a role in framing our laws around this class of drug and in limiting our ability to use psychedelics for medical research. Only by understanding the early history of LSD can we properly assess the current discussion around the “psychedelic renaissance,” the next boom in the pharmaceutical industry. We must understand the flawed logic that limited therapeutic uses for psychedelics in the first place, because understanding the roots of that logic may, at long last, allow us to embrace fully the benefits of these drugs.

The first step to helping patients in need of psychedelic therapy—people like my mother—begins not in the present or in the future, but in the past.

Berlin, 2023

__________

* Pickard had once practiced with the same Zen master as Steve Jobs—and taken the same LSD as Jobs, who credited one of his trips with the inspiration for the desktop computer.

PART I

MEDICINE

1

THE ZONE

WHEN THE FEDERAL BUREAU OF NARCOTICS AGENT ARTHUR J. Giuliani took up his post as narcotics control officer in the American sector of Berlin on April 8, 1946, he was thirty-seven years old and spoke, to his credit, a bit of French and Italian, both picked up on the streets of New York, but not a word of German. The former capital of the Reich was on its knees; the wounds carved by British and American bombs on the one hand, Russian artillery fire on the other, were still everywhere present. Rubble formed an eerie street-scape where the ghosts of the past roamed, while the geopolitical conflicts of the future were already making themselves felt and the battered residents were searching for the precious commodity of normalcy. Berlin was a place gone completely out of control, a place it hardly seemed possible to regulate; only bit by bit were the women who made up the rubble crews able to clear the streets and make them passable again. Here was a blasted metropolis in which thousands of people lived in ruins, almost all of them out of work, caught in a state between exhaustion and the exciting prospect of starting life over again from scratch.

The shattered economy created a paradise for grifters and dealers. Anyone in need of the most basic necessities had to turn to the black market, where they could find anything that wasn’t bolted or nailed down, from prosthetic limbs to garters. These illegal markets popped up in more than three dozen locations, East and West, each with their own mixture of suspicion, desperation, and just a hint of gold-rush atmosphere, all manifestations “of the complete despair, confusion and cynicism now reigning in Berlin,” as the Washington Daily News reported.

Hershey bars, graham crackers, Oreos, Butterfingers, Mars bars, Jack Daniels: for consumer goods such as these, war-battered Germans were prepared to part with everything from their Leica camera to their left kidney. A Knight’s Cross for a Snickers! A pocket watch for a bit of margarine. Women got dolled up and offered their bodies as goods for barter. Shady characters paced back and forth, whispering appeals to passersby, several watches on each wrist, an array of medals pinned to the inner lining of their long coats, hats tilted rakishly back on their heads and a cigarette ever dangling from their lips, assuming they could get one. Allied soldiers waved fistfuls of money that they weren’t allowed to send home. A contemporary criminologist summed up the situation around him: “The phenomenon of crime in Germany has reached a level and forms unparalleled in the history of western civilisation.”

What was evident everywhere was a “deprofessionalisation of criminality.” In Berlin it seemed as if everyone had a secret, everyone cheated and swindled; they couldn’t survive otherwise. Illicit dealings were part of the everyday life of the population at large; the underworld exerted an irresistible force of attraction on what was left of decent society. Laws were no longer respected; Hitler’s rigid dictatorship was a thing of the past, and now it seemed like everything was allowed: “an environment where black market dealings are a common form of law violation.” Zapp-zarapp, the Russian loan word for the act of “taking something from someone else with a quick, scarcely noticeable motion,” had become ever present.

The four occupying powers, the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France, had their hands full in this Berlin that was now ruled not by the Nazis but by primal instincts, by the will to survive. “Working parties” were formed among the Allies to deal with various issues, including the urgent question of regulating the drug trade, which had gotten out of control.

One problem was the enormous quantities of narcotics that had been salvaged from the stores of the defunct Wehrmacht or taken from the ruins of bombed buildings and put into circulation: Pervitin, produced by the Temmler company and containing methamphetamine; Heroin from Bayer; cocaine from the Merck company in Darmstadt, supposedly the best in the world; Eukodal, the euphoria-inducing opioid that had been Hitler’s drug of choice, likewise made by Merck. With living conditions as difficult as they were, more and more people took recourse to substances to help them get through the day—or the night. Drug offenses rose by 103 percent in the first six months of 1946, compared to a rise of 57 percent in other crimes. On the black market, “enormous prices” were demanded “for smuggled drugs”: 20 Reichsmarks per injection of morphine; 2,400 Reichsmarks for fifty pills of cocaine, 0.003 grams. Giuliani was troubled by these high margins, fearing that the “profits . . . could be used by the Nazi underground.”

In his final letter to Washington before throwing in the towel, Giuliani’s predecessor Samuel Breidenbach had compared postwar Germany to the Wild West. But the new arrival wouldn’t be rattled so easily. He resolved instead to establish order and lay the groundwork for a new set of drug laws that would be in effect for all of Germany. This was a challenge that the narcotics control officer in his crisp new American military uniform was happy to take on. It didn’t hurt that the War Department paid him a salary that was a fourth higher than what he would have earned in a civilian post. The conflicting interests of the different occupying powers all trying to pull Berlin in this or that direction didn’t faze Giuliani too much as he went about his work. After all, he, being an American, was bringing peace, prosperity, and freedom—and what could be wrong with that?

Not everyone took a negative view of the chaos. The writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger was seventeen years old at the time and didn’t have to go to school because there was no longer any school to go to, not yet anyway. His biographer described the shattered world as a place of learning: “Even without school we can now learn a great deal about politics and society: we learn for example that a country without a proper government can be a very pleasant thing. On the black market, you learn that capitalism always gives a chance to the resourceful. You learn that a society is something that can organize itself without central orders and guidance. In conditions of scarcity you learn a lot about people’s real needs. You learn that people can be flexible, and that solemn convictions may not be as unshakeable as they seem. . . . In a word: in spite of hardship it is a wonderful time if you’re young and curious—a brief summer of anarchy.”

Even Arthur Giuliani, who set up his office at American headquarters in Berlin-Zehlendorf, couldn’t deny his fascination with the unusual circumstances: “It is utterly impossible to realize the completeness of Berlin’s destruction,” he wrote to Harry J. Anslinger in Washington. “Perhaps after years, a fair amount of information can be dug out of the cellars where it now lies buried under the tons of debris which once constituted the buildings above it—but that time is not yet in sight.” He kept himself busy, confiscating something here, arresting someone there, and sending photos back to FBN headquarters as proof of his activities. The photos captured a pair of women’s shoes with hollowed-out heels for hiding narcotics, car doors with armrests full of drugs, potatoes with their insides removed. A Hershey’s cocoa tin filled with cocaine. A ladies’ slip soaked in heroin solution. A book with a hole carved into its pages that in lieu of reading material offered a different kind of food for the brain.

In reality, however, such minor investigative successes had little effect. The problem was structural in nature. After the old National Socialist authorities had ceased to exist, a vacuum had opened up for the illegal dealers to exploit. How was Giuliani supposed to remedy the situation? Then one day hope arrived from an unsuspected source. He received a letter from a former Gestapo agent by the name of Werner Mittelhaus. “It is a long time my intention to write to you because I wish to tell you about the activity of the ‘Reichszentrale zur Bekampfung [sic] von Rauschgiftvergehen’ during the last years of the war.” It was there, at the Reich Headquarters for Combating Narcotic Crime, that Mittelhaus had been employed, and in his accented English he voiced a wish: “I myself would like very much to work again in drug offices . . . I suppose, you will have an interest on such a work in Germany, and I would be glad, if I could cooperate in a common combat of the drug smuggle.” He concluded his offer by saying, “I was never a member of the SS, only a member of the NSDAP on order of my department. The proof of my anti-Nazi positions are in my hands.”

The offer presented Giuliani with an ethical problem: Would he accept help from a former Nazi, profit from his expertise, let the man tell him how to police the streets of Berlin? It was a dilemma that the other Western allies were also caught up in, whereas the Russians made no compromises on this point. Giuliani discussed the idea with Anslinger, who had no scruples about it and gave the green light from Washington. “You might check up on Mittelhaus as being possible good material for our organization.” From Gestapo to FBN.

In fact, the head of the FBN admired the defunct Nazi regime for its strict policy of prohibition. “The situation in Germany . . . was entirely satisfactory,” he wrote. In contrast to the chaotic Weimar Republic, the Nazis had kept their house in order. “During 1939, for instance, and as compared with 1924, this decrease [in the consumption of drugs] amounted to 25% in the case of morphine, 10% in the case of cocaine,” Anslinger noted. “Thanks to the careful supervision, smuggling [was] practically impossible.” Indeed, “narcotic law enforcement is believed to have been very efficient in pre-war Germany.” In November 1945 Anslinger had praised the old Nazi drug laws as a model for America: These were “stricter” and had a “better constitutional basis than our own,” for which reason he resolved to study the control mechanisms used in Germany and in the German-occupied countries and territories during the war. His goal: “The old and successful German opium legislation [should] become operative again as quickly as possible and be applied with the same severity as in the past.”

The Nazis had made quick work of drug-users, packing them off to concentration camps—for Anslinger a welcome approach. The high-ranking American government official clearly wasn’t bothered by the ideological thrust of the Nazi drug war, by its being directed against Jews, with their supposedly higher level of drug consumption. He openly acknowledged his own racism, once describing a Black informant with a racial epithet in a letter to FBN district supervisors. Another characteristic statement of Anslinger’s is this one made before the US Congress: “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.” It’s no surprise that in Washington he was openly referred to by the nickname “Mussolini”—and not just on account of his unfortunate appearance.

For Giuliani, making contact with the ex-Gestapo agent proved difficult: By this point Mittelhaus, the former officer of the once feared Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), which had operated under the direction of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, had resettled in Kiel to avoid being arrested by the Russians. The British military was stationed up there on the coast, and it, too, expressed interest in working with him.

“I spoke to the British Zonal Safety Officers, who communicated with their office at Kiel,” Giuliani wrote to Anslinger. “He [Mittelhaus] will probably be re-employed by the German Criminal Police in the British Zone when he is cleared.” The Brits described their catch as “undoubtedly efficient and reliable,” and his connections as “amazing.” Giuliani’s conclusion: “The British have no intention of turning him loose, which is both understandable and reasonable, considering the personnel problem all over Germany.” Also urgent was the Western Allies’ belief that they required the help of former Nazi functionaries to keep German society running. Finding personnel was no easy task.

But the narcotics control officer found a solution and met instead with another former Gestapo agent, one named Ackermann, an “able, energetic, and intelligent” ex-Nazi who “was able to give [Giuliani] all the information that Mittelhaus could” have given him, including on drug smugglers and their current whereabouts. Ackermann could also provide copies of Gestapo forms for reporting narcotics offenses and instructions for Nazi drug policemen in active service. Such documents were of interest to the American, potential blueprints for forms he might use himself. At these meetings Ackermann lamented that the old Nazi law was “being distorted through diverse interpretation, and [was] losing some of its efficiency thereby.” Giuliani in turn hoped that “the activities of the working party here in Berlin would tend to correct this.”

The American was sorry that he couldn’t put Ackermann on the payroll, but said, “I feel certain that, in our Zone, he would fall through denazification.” One thing, however, seemed clear to Giuliani: The only course of action with any hope of successfully getting a handle on the unchecked drug trade in Berlin and Germany was to establish “a central operational set-up through which information on the narcotic traffic, both lawful and unlawful, [could] be channeled to a central control authority.” Such an authority, similar to the former Reich Health Office (Reichsgesundheitsamt) under the Nazis, should be “national in its scope.” As his predecessor Breidenbach had put it, because of “the very nature of the illicit narcotic traffic, its utter disregard of national frontiers, and its frequent efficient organization on an international scale, it is my studied opinion that no set-up short of a centralized national administration will prove effective in preventing the development of an extensive illicit narcotic traffic in Germany. Any attempt at independent control in separate zones, without a strict inspection and control of all mail, commerce and travel from zone to zone will be inadequate.” Anslinger had described the urgency of adopting a centralized approach in similarly clear terms—“it is an international experience that lawless conditions in the domain of drug traffic will not stop before frontiers”—while Breidenbach outlined the stakes for the United States: “Should any extensive illicit traffic develop the United States would be one of its principal victims, regardless of the zone in which the clandestine trade might have its origin.”

At this point Giuliani proposed adopting the Nazi regulations and Nazi drug laws wholesale and merely replacing German designations with their English equivalents. He put together a list:

1. “Reichsgesundheitsamt” shall mean “the Central Narcotics Office for each Zone of Occupation.”

2. “Landesopiumstelle” shall mean “Opium Office of the Land or Province.”

. . .

5. “Reichsrat” shall mean “Allied Control Authority.”

6. “Reichstag” shall mean the “Allied Control Authority.”

Anslinger liked this approach, especially since it was to be implemented under the leadership of the United States. His plan was for Giuliani’s work to have an impact that wasn’t limited to Germany alone. The goal of the US’s top drug enforcer was to implement a global “policy shift toward a strong policy of prohibition” by means of the newly founded United Nations. What he had in mind was nothing less than to create a regulatory framework for combating the drug trade that would be applied to the entire postwar world. Continuing the racist methods of the Nazis, who had perfected the notion of “combating narcotics” as a means of oppressing minorities, was fully consistent with his worldview. Because of the importance of its influential pharmaceutical industry before the war and its geopolitical position as a hub in the middle of Europe, Germany for Anslinger took on a key role and was meant to function as an example. If strict national controls could be successfully reintroduced between the Rhine and Oder rivers, a uniform international regulatory system would become more of a possibility. At his first appearance before the UN in December 1946 as the American delegate to the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs, Anslinger, building on Giuliani’s experiences in Berlin, presented a globally scalable, Washington-dominated approach to drug prohibition. His plan was to reshape the UN drug commission into an enforcement body that would implement repressive measures as well as a uniform anti-drug protocol binding for all countries.* What he absolutely did not want was for the commission to develop merely into a pluralistic discussion forum that would permit varying views on the potent substances. His aim wasn’t easy to achieve, since not every country was on board with the idea of international prohibition—not by a long shot, and especially not those that produced a lucrative opium crop, such as Iran, Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Afghanistan.† Countries such as these soon became a thorn in Washington’s side.

In Berlin, meanwhile, which according to Anslinger’s plan was supposed to lead the way, the situation also proved to be a challenge, owing to the city’s division into four sectors. Even if the Allies insisted that they wanted to develop a national framework for Germany, each had their own interests to pursue, especially where drug policy was concerned. The British were concerned first and foremost with keeping the war-ravaged German pharmaceutical industry small, while the French in general took a lax approach. “My meeting with the Frenchman was very unsatisfactory because he knew nothing of the proposal and less of the Opium Law,” Giuliani complained after a discussion with his counterpart from Paris. “I talked and talked and got no sign of intelligence from him. He was exceedingly cordial . . . but it was discouraging talking in the face of ignorance.”

The Russians meanwhile threw a wrench in Giuliani’s plans. They downright refused to go along with the plan to adopt the Nazi approach. At meetings of the Narcotic Control Working Party, held every few weeks in Room 329 of the Allied Control Council building in Berlin’s Kleistpark, every attempt by the American to get all parties to agree upon prohibition for all zones was quashed by Giuliani’s counterpart with the red star on his uniform cap.

Growing ever more frustrated, Giuliani turned to Washington and sent reports of “downright sabotage on the part of the Soviets.” On a personal level he got along with Major Karpov, and they often ate lunch together. “I get along well with the Soviet informally. He is a stodgy ideologist. This, I find is true of most Soviets. They hew to the line with stupefying monotony.” As soon as the meetings of the “working party” commenced, it was “hard” for Giuliani “to do business with” him. Karpov, along with his colleague Major General Sidorov, regularly rejected proposals to form an anti-drug commission spanning all sectors and to strengthen laws. This led to heated debates in which “many four-letter words pass[ed], sotto voce, among the delegations on all sides.” Giuliani wrote of “Irretating [sic] frustration” that was “rough on the nerves.” To Washington he wrote: “It has always been apparent that the Soviet Member intended from the start to sabotage any attempt . . . to achieve uniformity of application.”

Utterly disgusted, Giuliani summed things up on November 14, 1946: “It was ob[v]ious that the Soviets have every intention of blocking the general proposal . . . The objections of their members was based on a[n] inexplicable perversity. All of their arguments were couched in terms which can only be described as egotistics [sic].” At this point Anslinger asked Giuliani for “a report . . . on the situation in Germany showing what [was] happening in the four zones on narcotic control and how the program [was] deteriorating due to lack of central agency,” and requested, “Also show the blocking tactics by the Russians and the fact that the Working Party is just about a washout.”

Giuliani got to work and wrote the desired report from Berlin. Anslinger used it to bolster an argument he had earlier made before the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs accusing the Soviet Union of trying to flood the West with narcotic substances in order to destabilize its democratic societies—a claim that far outpaced Giuliani’s assessment.

Thus the failure to keep Berlin and Germany together and prevent the Western and Eastern sectors from drifting apart was manifested at the level of drug policy as well. Because Moscow balked, the Americans didn’t succeed in implementing a unified prohibitionist policy for all four zones. The German capital still lay in ruins, and Giuliani’s efforts as narcotics control officer were for naught. Summing up his work in Berlin, he sounded ambivalent: “No matter what I accomplish here, I will always recall this experience as the most unusual I have ever had.” This much at least had become clear to him: If his boss Anslinger was going to wage a global war on drugs, he was going to need a lot of staying power.*

__________

* Even if Anslinger was never able to put all his radical ideas into effect, in 1961 the United Nations passed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, whose goal, still today, is to fight drug abuse through coordinated international action. In this measure passed by the UN, cannabis, which Anslinger characterized as “the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind,” was for the first time declared an illegal plant throughout the world (Herer, Hemp and the Marijuana Conspiracy, 29).

† Anslinger also had concrete material reasons for wanting to prohibit global drug production, and especially production of opium: Back in 1939 he had arranged with the American pharmaceutical industry to stockpile a large quantity of the substance so as to be able to supply not only the US, but also its allies in the Second World War. He had channeled public and private funds to opium producers in Turkey, Iran, and India, and in 1942 instructed the American Defense Supplies Corporation to acquire all available stocks of opium in preparation for a long conflict. Ten trucks filled with close to three hundred tons of opium, guarded by FBN agents with machine guns at the ready, had driven from the ports of the East and West Coast to Fort Knox, where the United States’ gold reserves are stored. There the raw material was unloaded and taken to the pharmaceutical companies, where it was turned into opiates and opioids. By 1943 the Western Allies, who used these products to treat their wounded, had become dependent on exports from the US when it came to opium derivatives, and Anslinger had secretly turned himself into the head of a global drug market—a de facto global drug czar with the backing of the American government.

* And indeed he had it: Anslinger outlasted five US presidents over the course of his time in office and was, second only to his rival J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, the longest serving top-level government official in Washington. One administration after another inherited and continued his structural institutionalization of racism under the cover of a comprehensive policy of drug prohibition. Beginning in the 1930s, when the anti-drug laws that Anslinger prepared first went into effect, only to be tightened over the course of the ensuing decades, more people of color than white people have been arrested for possession of controlled substances, even though there are more white drug users. Ever of crucial importance was where the police patrolled and how hard it came down: in a word, racial profiling.

2

FROM PAINT TO MEDICINE

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN EAST AND WEST OVER DRUGS INtensified when the world became aware of a new category of substances. Where before the drugs whose use and regulation posed problems to society and sent Giuliani tramping through the rubble of Berlin had either a stimulant or a narcotic effect, now a third class emerged that was even more difficult to get a handle on—and would become a source of increasing contention over the years.

Unlike amphetamines or opiates, where there seems to be a general understanding of the relationship between medical utility on the one hand and health risks like addiction or bodily harm on the other, this new category poses unknown challenges for doctors, therapists, drugmakers, and lawmakers—not to mention those who actually consume the drugs. The substances in question are the psychedelic drugs, such as LSD and psilocybin, which at the present moment are experiencing a renaissance and are responsible for a rise in both the stock prices of those companies that have made them their focus and the hopes of everyone else who sees in them a promise of relief from illnesses such as dementia, depression, or anxiety disorders, which so far have proven scarcely treatable. These substances also fall under the jurisdiction that Giuliani and his boss Anslinger established, and the question of how to deal with them has to this day caused ever-increasing conflict. Unlike cannabis, whose global legalization is imminent, these substances that have such a strong effect on the human mind are still bound up with taboos, the discourse dominated by fear and disinformation.

With all this as background, I stumbled upon a white paper put out by the American start-up Eleusis, which has taken on the task of “transforming psychedelics into medicines.” Preliminary clinical studies conducted by Imperial College in London show that LSD activates the very receptors in the brain—known as the 5HT2A receptors—that atrophy as a result of Alzheimer’s disease. When I read this, I snapped to attention. This concerned me on a personal level: My mother suffers from this aggravated form of dementia. The brain, which Alzheimer’s gradually puts to sleep and ultimately kills, could—so claims the report, published in 2020—potentially be reawakened by the continual administration of low doses of LSD. Extensive studies were still necessary, but there were indications that the substance represented “a promising disease modifying therapeutic” for Alzheimer’s. Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form connections—was demonstrably encouraged, and the neuroinflammation that is held to be a contributing factor in dementia reduced.

The origin of the most potent variety of this new class of substances, LSD itself, dates back to shortly before the end of the First World War. At that time, there was an increased demand for paint brought about by reconstruction efforts throughout Europe: Everything that lay in ashes and ruin was to be rebuilt and given a fresh coat. The world was supposed to shine like new, to be bright and colorful, and the times were auspicious for the chemical industry in Basel, a centrally located city that had been spared by the war, Switzerland having remained neutral. Sandoz, a paint manufacturer owned by a French-Swiss family, did good business thanks to the increased demand and decided to invest in a pharmaceutical branch, where the potential for growth was seen to be even greater. The leap from manufacturing paint to producing medicine was in fact a logical progression. Around the turn of the century, companies in Germany had developed chemical dyes that also found medicinal use. The substances, known as thiazines, were compounds of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur that had sedative effects. Some dyes also had antibiotic effects; one, called trypanrot, was used to treat sleeping sickness; another, methylene blue, to treat malaria.

In any case, the decision to branch out from paint to medicine seemed economically sound: People would always get sick, especially after a world war, with its manifold long-term aftereffects. There would also be more and more people who had money to spend on medicine. The golden years of the pharmaceutical industry began, and one of its pioneers, who would become the unwilling forefather of consciousness-altering substances, was Arthur Stoll, a complex figure whom some would later call a “monster,” others a benefactor and man with “community spirit.”

Richard Willstätter’s Berlin laboratory, 1913, with assistant Arthur Stoll (left).

Arthur Stoll was born in 1887 in the Swiss wine-growing village of Schinznach. At the age of twenty-two, as a student at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich, he met the scientist Richard Willstätter, one of the founders of biochemistry, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on plant pigments. Their meeting was a lucky break for the talented young Stoll. In 1912 he followed his mentor to the newly founded Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin, where Otto Hahn also conducted his research and would later become the first to successfully split the atom. In 1916 Willstätter and Stoll moved on to Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, where at thirty years old Stoll was named Royal Bavarian Professor by King Ludwig III, a lifetime appointment. But the overachieving Stoll was less interested in teaching and fundamental research than he was in the practical development of medicines; it wasn’t academic honors that he had his eye on so much as the profits to be made in the booming drug industry.

To Willstätter’s surprise his best student left him right at the triumphant moment of receiving his early professorship and went back home to Switzerland to build up the new pharmaceutical line at Sandoz—a unique, daunting task. Stoll’s start-up had modest beginnings: “The laboratory, which when I took over on October 1st, 1917 was an empty room without any fixtures or furniture, had to be equipped in the most simple manner imaginable with glassware and other instruments,” he later described.