0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

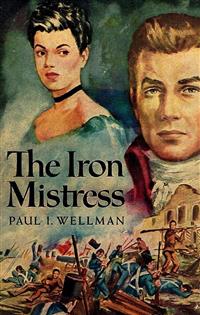

A quite extraordinary piece of historical recreation in a biographical novel based on the life of Jim Bowie, whose name has been immortalized in the “bowie knife”. From the time of his youth, his was a life teaming with the spirit and mood of a frontier region. Bowie found New Orleans and particularly its women tempting and alluring. He won renown as a duelist and his famous knife - “the iron mistress” - served him well, but romance caught him unaware and hurt him to the core. Above all, his prowess, his dauntless courage, his ingenuity in achieving impossible goals won him fame and notoriety.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Iron Mistress

by Paul Iselin Wellman

First published in 1951

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Iron Mistress

by Paul I. Wellman

To Joyce,

WHO KNOWS ALL THE WAYS TO A MAN’S HEART,

“By Hercules! The man was greater than Caesar or Cromwell—nay, nearly equal to Odin or Thor. The Texans ought to build him an altar!”

—Thomas Carlyle, speaking of James Bowie.

New Orleans, 1817

New Orleans was, yet was not, a city of the United States in the year 1817. Since Thomas Jefferson’s great land purchase of 1803, it was recognized as a part of the young American nation by all the world powers. New Orleans, however, had difficulty in so recognizing herself.

In all essentials the city remained a self-contained extension of Europe. Its languages were French and Spanish; manners, arts, cuisines, and customs were Continental; and New Orleans did not forget that it had been what it was for a full century before its vicissitudes threw it to the upstart young Republic of the north.

Americans? The people of New Orleans, and especially the women, regarded Americans as barbarians, who lived, presumably, on a diet of gunpowder and whiskey, and had too much natural violence to be permitted in polite company. Such Americans as came to the city for business reasons quickly discovered it was more convenient and pleasant to live in the new suburb, known as the Faubourg Ste. Germaine, than to encounter continually the superciliousness of the haughty Creole families of the Vieux Carré.

Yet New Orleans was to discover that isolation from the United States, however to be desired, could not long continue. Already in 1817 the process of change was becoming manifest. Its cause was the river: the Mississippi, which was the one great trafficway of the Central Continent.

That year its mile-wide flood carried countless craft of myriad kinds. Steamboats fought upcurrent with threshing side wheels. Ocean-going cargo ships with masts towering incredibly skyward tied up at the wharves. But chiefly the river brought down homemade craft of the frontier, drifting like chips on the current: scows and bateaux, arks, flatboats, broadhorns, barges, keelboats, and even rafts. They were laden with wheat and corn, pigs and poultry, furs, lead, hemp, tobacco—anything to fill the great stone warehouses on the water front, the lusty commerce of a lusty people seeking outlet.

Willy-nilly, fate was overtaking New Orleans in 1817.

Chapter One

1

The cracked bell in the central tower of the Cathedral of St. Louis splintered the air with sound: an immense, accusing voice directed at the last stragglers to Mass. Under the profound arches of the Cabildo young Jim Bowie stepped back to let the people hurry by, and could not help gazing at the marvels of this city with all a back-countryman’s unreserved delight.

He was a tall youth—notably tall—with a hunter’s tan, a square chin, fair hair, eyes sometimes blue, sometimes gray, and shoulders spreading mightily. He smiled much, and his teeth were magnificent. Most put him down as of a sunny nature, and they were correct. A man might cross him once, or even twice, and get no more than a stare, or perhaps a smile, or even a little apology. But the third time he would be likely to find himself flat on his back from a flailing fist, and if he wanted to carry the matter further, he would be accommodated: though if he preferred to call it quits, Bowie was willing enough to shake hands on it and forget the quarrel. For he was a curious alloy of opposites—a blend of kindliness with savagery.

As if reproaching the tardy, the cathedral bell gave a last expiring jangle and fell silent. In the comparative stillness that followed the subsidence of its mighty voice, Bowie leaned against the stone wall in the shade and listened to the footsteps: quick strides of Creole gentlemen in Hessian boots, soft shuffle of barefoot Negroes, the evocative click of women’s small heels. All hastening to worship. This was May, a Sunday morning, the youth under the arches was just twenty-two, and it was his first day in New Orleans.

Across the street raked the iron pickets of the Place d’Armes, a grassy oblong flanked by flower beds and chinaberry trees. The sky was a limpid vault of blue above. A gorgeous day, he considered, although New Orleans folks certainly preferred the shade. One or two did hurry across the open square in the sun, but all others chose the shadow of the Cabildo arches, or those of the Presbytère opposite, even if it meant being tardy to prayer. These Creole women were inordinately careful of their famous magnolia complexions: the men, it seemed, scarcely less so. In the case of the women at least, Bowie conceded that the complexions were worth all the trouble: he had never seen anything prettier, in spite of the way they looked down their noses at an American.

Catholics and foreigners, he thought: yet even with that he knew himself to be the real outlander, and so regarded. A pity, too. Bowie stared at the women passing. They walked and held themselves in a manner proud and graceful and also subtly challenging, so that it was a pleasure to look upon them, as if somehow they made mankind more important and creditable merely because they happened to be a part of it.

He straightened and stood tall, close to the wall, as two Creole girls went by. They were young, in their teens, but women ripened early here and these were most beautifully self-possessed. About their feet their light dresses foamed, the tips of tiny slippers just peeping from beneath now and then, almost furtively, and precious to behold because so infrequently visible. On their heads were white shawls. Of the young man beside their path they seemed unaware, chatting lightly in French. Bowie spoke both French and Spanish, having grown up with them in the bayou country: but this was different from his Cajun patois. Softer and with phrases to which he was not accustomed. Very cultivated French, he assumed, because all Creoles were very high-toned and cultivated and full of airs.

Though they appeared not to see him, he took note that in passing they gave him pointed and unnecessary room. And at the moment when he was staring at their side-faces, he thought he caught a glance from the nearest: a mere gleam, of which he could not be sure, because her lashes were so sweeping that they masked the look, if it were given. Still, he felt she had glanced at him. It was not much, but to a young man it was better than if she had failed to notice him altogether.

His eyes followed her. She was tiny, not even five feet tall, and entirely exquisite. A faint subtlety of fragrance was left on the air by her passing, and her waist was of a stemlike slenderness which his two big hands could have circled without squeezing.

With discontent he glanced down at himself, for she reminded him of his own vastness and clumsiness, matters of which he had not even been conscious before coming to this city where a tapering hand, a small wrist, and a slight and elegant figure were esteemed as much in a man as in a woman, as marks of gentility. On this Sunday morning he was arrayed in his best: coat of dark blue broadcloth, nankeen breeches, white stock, vest of watered silk made by his mother with her own hands, low-crowned black wool hat, and boots gleaming with lampblack and grease. He had felt very fine in Opelousas: but what seemed fine there cried the provincial in every line here in New Orleans.

Everywhere he saw tall bell-crown beaver hats, long-tailed bottle-green coats with shoulders craftily cut and padded instead of merely being stretched to the point of bursting as his shoulders stretched his own garment, cravats instead of stocks, and Hessian boots which fit close to mid-calf and sported tassels as the last breath of sophistication.

Most keenly Bowie felt his bumpkinhood: his hands and feet too large, his height an un-Creole exaggeration of stature, his complexion unfashionably bronzed, his way of walking like that of an elk—long, sure strides and a great swing, good for many miles of forest between dawn and dark, but hardly elegant in a drawing room. But a young man, even when abashed, finds it difficult to keep his eyes from the figure of a pretty woman: so he watched the two slim, disdainful shapes until they disappeared into the cathedral.

For the first time, then, he noticed at the door two men, evidently in some brief argument.

One seemed to be importuning; the other, elegant and elderly, with a gray spike beard, made an angry gesture of refusal, tore himself from the detaining hand, and hastened within. The man who remained outside stood with his head bent in an attitude of profound dejection, gazing at a huge black portfolio which he held under his arm: a quaint figure, slender and of middle height, dressed very shabbily in purplish drab, with fair hair long as a woman’s, caught at his nape by a bit of black ribbon, and hanging down behind his shoulders.

Bowie wondered what the argument was about: but it was none of his affair. The cathedral had drained the Rue Charteris of all its people, save the man with the portfolio and himself. Beyond it was the Rue Ste. Ann, running to the river, and at the foot of the Rue Ste. Ann lay the docks of Janos Parisot, the merchant. It occurred to him that he might find that important personage there this morning, so he started along the banquette past the cathedral.

Through the open doors he caught a momentary glimpse of vast hollow twilight, pillars receding and altar candles afar. The murmur of the people at prayer came to him like the droning of insects.

“M’sieu——”

A voice of pleading. Bowie halted. The man with the portfolio had stepped aside for him but regarded him with a strange attentiveness.

“Sir,” the man said, changing to English, “thee be Américain?”

The accent was faintly French, yet with a Quakerish style to the words that was puzzling. Bowie surveyed him. He was clean-shaven, tanned, and not unpleasing, though his features were a little fine-drawn as from some weariness. His age would be in the early thirties.

“I am,” Bowie said.

“Of the Faubourg Ste. Germaine, belike?”

Bowie shook his head. “Of the Bayou Boeuf, in Rapides Parish.”

For some reason the other’s face lighted. “A hunter, perhaps?”

“At times.”

“I knew it! I knew thee could be none of the trading tribe! By thy eye I knew it. And by the set of thy feet, the one straight before the other as on a forest path! Friend, give me thy opinion on this?”

Surprisingly he went down on his knees before the cathedral doors, laid open his black portfolio, and drew forth a great sheet of paper splashed with color. A painting. He held it up for examination in a way timid, yet somehow appealing and confident, like a young mother holding up her firstborn babe for approval.

“Wild turkey!” exclaimed Bowie.

“The great American cock,” the other replied with dignity, in spite of his kneeling posture. “Meleagris gallopavo, to science. Thee knows the turkey?”

“If I had a shilling for every one I’ve shot——”

“In such case, will thee point out any imperfection in this representation?” The kneeling man eyed him challengingly, as one who awaits judgment with complete confidence.

“Imperfection?” Bowie stared with genuine amazement. “Why, none, sir, that I can see. It’s the very bird—his glittering eye—the wattle and tuft—the way he lays back his wing—I’ve marked that set many a time. It’s like as if he moved before you—every feather in its proper place and true to pattern—why, there’s even the sheen of bronze where his gorget catches the sun! Man, is this your work?”

“Aye.”

“Then where did you get the trick of it?”

Instead of answering the question, the stranger said, “Thee might care to see more paintings of this order?”

Bowie nodded. In an almost childlike enchantment with the picture he had forgotten his errand and Monsieur Parisot.

The other drew a deep sigh, his woe changing to elation. “Friend, thy praise uplifts me! To find one who sees—and knows!” He grew somber again. “They do not want my birds. Yet how I slave—in the pirogue in the marshes from dawn to dusk—then tramping the streets seeking commissions to paint portraits of spoiled smirking beauties or arrogant rich men who want only that their vanity be flattered—so that I may buy me a little bread.”

So bitterly rose his voice that one of the vergers came to the cathedral door and frowned at them for quiet.

“And of them all not one who will so much as glance at my birds—my beautiful birds,” moaned the artist, lowering his voice. Amazingly his expression became cheerful again. He replaced the painting in the portfolio, tucked it under his arm, and sprang to his feet. “But at least thee will look,” he said eagerly. “I hold thee to thy promise! Friend, thee shall gaze at many paintings—glorious paintings of my birds!”

2

Together they walked along the Rue Charteris, and Bowie gaped at the stately Ursuline convent with its many chimneys and its dormered roof. Passing this, they turned up a side street and presently they came to one of the innumerable stairways giving on the street, so characteristic of the Vieux Carré.

“Let us go softly,” said the stranger, almost in a whisper. “My landlady is an excellent woman. But she has a—a prejudice against noise. Especially on the Sabbath. I would not disturb her——”

With what seemed unnecessary caution he led the way, tiptoe, to the hall above, where he unlocked a door.

At once an awful odor of death puffed out at them, swirling so overpoweringly from the room that Bowie stepped back from it.

“My heron!” cried the artist.

He seized Bowie by the arm, snatched him within, and shut the door behind him. The stench was such that Bowie was forced to hold his breath, yet he glanced about him with a mighty curiosity as his remarkable host hurried to the window and threw it open to the fullest. Everywhere the walls were covered with paintings, finished and unfinished. Papers with sketches and daubs strewed the floor and were heaped in corners. To one side stood a rumpled bed and a littered washstand, and by the window an easel. Now for the first time Bowie saw the cause of the dreadful odor. Near the easel, dead and putrefying, yet held upright on its long legs in some semblance of life’s erectness by an ingenious system of wires, was a swamp heron.

“Alas, ma belle,” wailed the artist, “I kept thee too long!”

Almost tenderly he disengaged the disgusting carcass from its wire braces and threw it into the alley. Then seizing a frond of palmetto, he vigorously fanned the air to clear the atmosphere.

“Nay,” he cried sharply, “open not the door! The worst will soon be out. And Madame Guchin is—well—strong-minded——”

When he felt he had sufficiently alleviated the unpleasantness, he tossed the palmetto on a heap of the branches and turned to the washstand to lave his fouled hands.

“The paradox of existence,” he said. “My heron dies, and rots, and the mongrel dogs of the street presently will devour her, and all that she may live forever. Voilà.” His hands dripped above the basin, but with his chin he pointed to the easel.

Bowie stepped to the window where the abominable smell had somewhat cleared. There was the heron, painted as in life, her feathers gleaming, her eye bright, the mirrored waters of her native swamp at her feet, tall palmetto palms in the background.

“Do thee like it?” asked the artist anxiously.

“Like it? It’s plain wonderful!”

“Then behold!”

With a flourish the artist opened the black portfolio and began to spread painting after painting on the easel before the window, All were of birds, and Bowie almost forgot the lingering taint on the air in his interest. Many he recognized, as the king woodpecker, which his host called the ivory-billed; the purple martin, courted by the Cajuns with little houses on tall poles because it destroys mosquitoes; the night-long aspirating whippoorwill; the brown pelican with great-pouched bill and surly eyes placed strangely in the top of its head; the stately, dazzling white egret; eagles and owls, hawks and gulls, partridge, quail, plover, geese and ducks, all familiar to his hunter’s eye. Most of the smaller birds, to which he had paid little attention in his hunting, he did not know, and his host delighted in naming them for him, seeming to think the least as important as the largest

“The tufted titmouse,” he said, “and a prothonotary warbler”—Bowie blinked at the big word—“and here a ruby-crowned kinglet——”

Expanding, the artist explained his method. He shot birds and used them for models, rather than the stuffed specimens which retained neither natural shape nor color. The wiring which held the dead creatures in attitudes of life was his own invention. He painted very rapidly, he added, because of the perishable nature of his originals—as witness the heron.

Once Bowie uttered an objection. The painting was spirited: four mockingbirds furiously battled a coiled serpent in the crotch of a tree where rested their nest.

“What’s wrong with it?” demanded the artist quickly.

“Mockers will fight—even a snake—it’s their nature. But rattlesnakes don’t climb trees—except maybe during a freshet——”

“And why not?” Resentful voice.

“Too fat and sluggish. It ain’t their nature. Rather go down in burrows after mice or gophers. Now a blacksnake——”

“Blacksnake? Artistic and dramatic sacrilege! Here thee see a poisonous fanged serpent—death itself—and the brave, brave birds——”

“A blacksnake may not be poison, but he moves like a whiplash. He’d be a sight more dangerous to your birds than any lazy rattler.”

“On what authority do thee say this?” cried the artist hotly. “Thee have seen, belike, all rattlesnakes in the world—that thee can say with surety that none climb trees for their prey?” He sneered. “It is I, friend, who am the naturalist. I am the student, observing all works of nature with the greatest scientific care!” His face paled, his teeth seemed to flash, his voice shrilled in surprising and quite unnecessary rage. “It is to be supposed that I—I—know not as much about the habits of snakes as some raw woods ranger——”

Bowie felt his own anger rising, as it does in most men at another’s causeless fury. But he wanted no quarrel, so without replying, he turned and walked abruptly out of the room.

Behind, the spate of words ceased. As he went down the stairs he heard the other come out of the door and stand on the landing. Then running steps pursued him, a hand was laid on his shoulder.

“M’sieu——” A soft pleading. “Forgive me. I—I am overwrought and—well—it is just that the truth is so very painful.”

Bowie allowed himself to be halted.

“Thee be most perfectly correct—of course—concerning the rattlesnake, wretched reptile!” The artist made a gloomy gesture of despair. “The charlatan’s touch—and I know it. Even as I painted it, I knew as well as thee that the sluggish rattlesnake climbs not in trees. ’Twas that made me screech so—my conscience pinched me shrewdly when thee put thy great finger square on my dishonesty.”

“It’s none of my affair,” said Bowie gruffly.

“But wait! I must confess to thee why I fell guilty of such sham. I had hoped through that one painting to gain attention for the others. There’s the truth of it! Do thee not think the world might find interest in the death-fight—look thee—between the beautiful birds and the horrid, venom-dripping serpent? And from that, belike, turn to my other pictures of—less melodrama? In God’s name, is a man to be damned utterly because he uses a small trick, perchance, for a good end?”

The tone was so imploring, the apology so complete and abject, that Bowie’s anger ebbed from him.

“At least give me thy name,” begged the shabby artist.

Bowie made up his mind. “If you want it, I’ll give it. And for the matter of that; I see no harm in the trick, as you call it, for nobody but a woodsman would ever question it. So—my name is James Bowie.”

“James? ’Tis my own second name, and we must be friends! I am John James Audubon, painter and naturalist, at thy service. My hand, James Bowie!”

3

Both had forgotten the injunction for quiet. Now they heard a door close in the hall above, followed by the grating of a key in the lock. Next a woman appeared at the head of the stair: a broad, dark woman of middle age, in lace cap and black bombazine dress, who looked down at them with the grimly hostile visage of landladies the world over. In her plump white fingers she held the key which Audubon had left in the door. The artist gazed up at her with a ludicrous combination of consternation, guilt, and anxiety.

“Good—good day, Madame Guchin,” he faltered.

In dour silence she stared down at them.

“Is—is that the key—of my room——” he began again.

Her harsh lips opened. “It is no longer your key, monsieur, nor is it your room.”

“My—paintings——?”

“Will remain where they are,” the woman said obdurately. “I may find them of more substance than your promises, which mean nothing.”

She turned her broad back and disappeared down the hall, as uncompromising and unassailable as a frigate which commands an estuary with its guns. Bowie glanced at Audubon. The man seemed caved in, shrinking, as if humiliated almost beyond endurance. His face turned white and he sat suddenly down on the step.

“Are you ailing?” asked Bowie.

“I am ruined. The work of years . . . my whole career——” Audubon’s eyes filled with tears, and Bowie, unaccustomed to the emotions of men of this type, was more impressed perhaps than need be by his new friend’s despair.

“You’re a little behind on your rent?” he said. “Would a loan——”

He drew out his wallet, but the artist rose with frigid dignity.

“Sir,” he said, “I own to a faulty memory, but I cannot recall asking thee or anyone for aid——”

Actually, the man was affronted! Bowie found himself apologizing for his own kindly impulse. The despair returned to Audubon’s face.

“You’ve got something worth more than all those paintings,” Bowie said.

“What could be worth more than them?”

“The art to make others, as good or even better.”

“Rattlesnakes, for example, that remain properly on the ground?”

A wan smile. That smile, under the circumstances, won Bowie. He placed a hand on the artist’s shoulder. To his surprise, it trembled. Intuition told him that the fine-drawn look he had attributed to fatigue might be something else. This shabby man, who painted nature with such miraculous fidelity, was famished, actually faint from hunger. He started to say something, remembered Audubon’s pride, and thought of a better approach. He grinned amiably.

“I mind a Cajun saying. A taste of salt makes perfect a soup, a salad, or a new friendship. If it suits your whim to go along with a little superstition of mine, Mr. Audubon, come have dinner with me, so we can taste salt together and thus seal our friendship.”

The artist looked at him sharply. But the grin remained disarming.

“To seal our friendship, eh? That seemeth well thought of——” He regarded Bowie closely again, then with sudden impulsiveness embraced him. “But from this moment call me John! As I shall call thee by thy first name—for I find that I love thee, James!”

Chapter Two

1

Down a street picturesque with the crowds emptied from the cathedral by the conclusion of Mass, Bowie and Audubon walked to the French Market. Once they passed two elegant Creole gentlemen, swinging sword canes, and Bowie got a go-to-hell look from them. Decidedly he was seeing a sufficiency of supercilious bell-crowns and sword canes this day. Yet he was never wholly indifferent to a brave show in the sun, and he privately thought that he could name a certain young man whose shoulders might do a great deal more for one of those bottle-green coats than any narrow-backed little Creole ever could do.

When they neared the French Market, close by the levee, a small, lively, wizened little man hurried toward them. He wore a hunting coat and sash, and his cheerfulness was undimmed by the ugliness of a scar that disfigured one side of his face and his nose.

“Jim!” he cried. “I wait for you since long time——”

“I got delayed,” said Bowie. “Mr. Audubon, this is my friend who came down with me—Jules Brisson, better known as Nez Coupé.”

“Coupé—that’s right.” The little Cajun indicated his disfigured nose with a laugh.

“The best hunter in the bayous,” Bowie added.

“Is not so! Jim Bowie is most best hunter in the bayous!”

He fell in beside them. Presently they arrived at a certain Café des Réfugiés, which Audubon had recommended as having a cuisine passable and prices low. Into a paneled room, the walls of which were plastered with handbills and posters advertising bull baitings at the Congo Square, rewards for runaway slaves, stagecoach schedules, and auctions, they were bowed by a rotund maître d’hôtel with elaborate shirt ruffles, who gave them a quick appraisal and led them to an inconspicuous corner.

Their table was near and slightly behind one of the two high-backed wooden settles which flanked a wide fireplace. From his seat Bowie saw that the alcove was occupied by a group of young men, of whom only the two at the end of the opposite settle were visible to him. It was evident, however, that all were Creoles, all were well dressed and arrogant. One, with a sallow face, a long lower lip which gave him a petulant look, and a slender black mustache curling foppishly around the corners of his mouth, stared at them, then leaned forward to say something that provoked a laugh.

2

The maître d’hôtel began to expatiate with a poet’s fervor on the excellences of the menu. Did the messieurs desire a potage? His potages were gastronomic triumphs. He could place before them, if they desired, oysters, terrapin, reedbirds, quail, ortolan, and other delicacies of the first style of culinary perfection. As they hesitated, he observed that the ragout of venison was a dream of gustatory bliss, and the brandies especially imported. Furthermore, there was la petite goyave——

“La petite goyave?” Bowie repeated.

Was Monsieur not familiar with it? The maître d’hôtel became ecstatic. Monsieur was in for a great, a notable experience. La petite goyave was the specialty of the house, most famous and most praised by many messieurs of discrimination the world over. He kissed his fingers in rapture. This sublimity, he said, was a drink brewed from the fermented juices of the guava fruit of the West Indies, very bland and delightful, once tasted never forgotten.

“Bring la petite goyave, then,” said Bowie, “and with it the ragout of venison—at once. My friends are hungry.”

Fat face dark with joyful perspiration, the maître d’hôtel hurried away and returned surrounded by a cloud of scurrying subordinates, who placed the dinner, smoking and savory, before them. With his own hands he brought a pitcher of amber liquid and glasses: poured, waited with an artist’s anticipation as Bowie tasted, and departed happily as the face of the guest showed that the drink was all it was advertised.

“Thee be drinking,” observed Audubon, “the favorite tipple of the old buccaneering crew—the Lafittes, Dominique You, René Baluche, and the rest.”

“The pirates? I’ve heard of them. Where are they now?”

“All gone but old Dominique. He’s around town, usually drunk.”

Audubon began wolfing his food like one starved. Nez Coupé also plunged heartily into the fare. But Bowie continued to sip la petite goyave, feeling a pleasurable glow.

In the alcove the young Creoles conversed noisily, with frequent laughter. Bowie became interested in a pair of legs which stretched forth from the end of the nearer settle, differing from the other legs in that they did not sport the prevailing Hessian boots. Instead they were encased in long, fawn-colored pantaloons, very tight at calf and thigh, with straps under the insteps of the small and shapely varnished shoes. He could not see the owner of the legs because of a wing of the settle, but part of an arm and a hand were visible. The latter, slender-boned as a girl’s and every bit as white, held a glass of la petite goyave, which it raised often to the hidden lips in a manner somewhat erratic, indicating a fairly advanced stage of tipsiness. Bowie decided that he did not care for the fawn-colored legs, or their owner.

3

Audubon, who had taken off the edge of his hunger, relaxed gratefully with his glass, and began to tell of himself—his childhood in France, with some horrendous accounts of the Terror; of the old sea captain who had adopted him, an orphan; of how he came to America as a youth, and was domiciled with a Quaker family, where he got his English speech with its queer thees and thous, his obsession over nature; and a wife, Lucy, a sweet and loyal, and also, Bowie gathered, a long-suffering woman, employed at the present as a governess in a household somewhere upriver, to support herself and her children, so her husband might find his destiny.

All at once he glanced down apologetically at his empty plate. “Forgive my garrulity. I was a-hungered, and drink at such times always makes my tongue overactive.” He looked up. “It will do no harm to tell thee that this morning I returned from a field trip of a week’s time . . . and my provisions ran out.” He paused. “But I sketched in colors a painted bunting—a magical flash of blue-violet, scarlet, and green—beauty to clutch the heart.” His face grew rapt, almost mystical, as it always did when he spoke of nature.

“ ’Twas in that absence,” he went on, “that my poor heron reached the state in which thee saw her. I had forgot her for days. Always in the forest I forget all else.” He smiled wryly. “One small matter I forgot was an appointment to paint the portrait of a young lady—a most beautiful young lady, or so she is accounted.”

The fawn-colored pantaloons in the settle-alcove had remained in full view, now stretching forth, now crossing their knees, now dawdling negligently. Audubon’s back was toward them, but Bowie was gazing at them as the artist uttered the last words. Perhaps he imagined it, but the fawn pantaloons seemed to tense slightly.

“From her father I accepted an advance of ten dollars,” Audubon went on, “against a fee of a hundred for the finished portrait. On that prospect I made promises to the good Madame Guchin—promises I could not keep. For since I forgot the initial appointment, the entire agreement is canceled. It was the father with whom thee saw me pleading at the cathedral—old Armand de Bornay, rich as Croesus with sugar plantations and black slaves. To him, ten dollars—or a hundred—is less than a picayune to me. Thee would hardly think him a pinchfist: yet from the furore over the trifling sum involved, thee might suppose it was the price of the Louisiana Territory.”

The fawn legs in the alcove drew up rigidly as if their owner suddenly sat erect.

Unconscious of this, Audubon shrugged. “But what would thee? The painted bunting—or the painted beauty? Peste, I prefer the bird!”

The owner of the fawn legs was on his feet: all the Creoles in the alcove had risen as if pulled up by invisible strings. The fawn legs stepped around the corner and their owner was revealed as a furiously angry young man in a long, swaggering, scarlet-lined cape. He was slight in figure, with an aquiline face quite handsome, though marred by recklessness and dissipation, and marked by black side whiskers trimmed very close and running to a curved point at the angle of his jaw. For a moment he stood scowling, then strode fiercely over.

“So I find you here!” he said to Audubon.

The artist bore a look of painful embarrassment, with an almost furtive side glance, as if he would have escaped to the outside—anywhere—had it been possible. “Narcisse——” he began weakly.

“You find time, it appears,” the other interrupted, “to drink in taverns, if not to carry out your engagements!”

“I beg of thee—my intentions were of the best. But—the day was perfect—I found myself in the pirogue—pouf!—a week was gone before I knew it! Ah, my friend——”

“Your friend? Have you the insolence to address me in such manner? Perhaps you consider that your patent to make scurrilous reference to Monsieur, my father—to ridicule Mademoiselle, my sister—and in a public place?”

“In God’s name, Narcisse!” Audubon was aghast. “I had no thought—an awkward phrasing, perhaps—but that only. My respect for Monsieur de Bornay and my admiration for Mademoiselle Judalon are beyond words. I apologize—most abjectly—for this misunderstanding. If thee wish, I will make my apologies to Mademoiselle—to Monsieur, thy father——”

The Creole’s lip curled. “You imagine you will have opportunity for that? The de Bornays open not their doors—for ‘apologies’—or any other bootlicking—to liars and dogs—fit only to be whipped like dogs——”

He raised a riding whip which he had in his hand, as if to lash the shrinking artist, but Bowie came to his feet, knocking over the chair behind him.

As one, the Creoles turned toward him, dark and angry, their visages hardening with dislike. Bowie towered over them.

“Messieurs,” he said evenly, “you were not invited to this table. I do not know the reason for the dispute, but I do know Monsieur Audubon desires no trouble with you. Be so good as to return to your own place.”

The young man with the scarlet-lined cape lowered his whip and looked Bowie up and down arrogantly. “Who may this be?” he inquired.

“My name is James Bowie.”

“So his name is James Bowie,” repeated the Creole, mimicking most offensively his way of saying it. “An Américain—since it is abundantly clear he is no gentleman——”

“As good a gentleman as you!”

“Vraiment? In that case you should know that a gentleman does not interfere in what is no affair of his.” The Creole’s voice was biting.

“What affects my friend is my affair——”

“And if not, you make it so? Is that it? Monsieur—what is it—Bowie? Monsieur Bowie! Mon Dieu, what a name! I suppose it would be impossible for any Américain to comprehend the difference between being a gentleman—and being a clown—a boor—a barbarian——”

On Bowie’s clenched fist the knuckles went white. But then he bowed, and the bow was an exaggeration. As he did so, he sought for a name, found it, and when he spoke his sneer matched the Creole’s.

“It seems I owe you some sort of an apology—Monsieur Lily Fingers. I had forgot that the conception of a gentleman in this place differs from that of the rest of the world. And that here such a creature should be treated for what he is—as obviously in your own case—a delicate and pap-nerved softling, as pale, as pretty, and almost as masculine as his sister!”

He had devised a brilliantly deadly insult. The Creole’s face went white.

“Monsieur!” His hand reached into an inner pocket of his coat.

Audubon and Nez Coupé were up, the latter dragging a short-bladed dirk from his hip.

“No, Nez Coupé——” ordered Bowie.

The Cajun hung poised, snarling like a catamount. In that electric moment Bowie remembered he was unarmed, and balanced on the balls of his feet, waiting for the other to draw.

“Narcisse! I beg of thee!” Audubon’s imploring voice.

The Creole gave a chill smile. “I said—I still say—the Américain is a born boor. But such as he is, perhaps he should be taught a lesson.”

From the inner pocket he brought—not a pistol—but a card case. Deliberately he drew out a small white oblong of cardboard and flung it on the table. Bowie took it up, experiencing a pang of chagrin that he had no card of his own to exchange for it. He read the name.

Narcisse de Bornay

“I am lodging at the Rouge et Noir,” he said stiffly. “My name you have.”

De Bornay bowed. Bristling, the Creoles tramped out of the tavern.

Chapter Three

1

“He will call thee out, depend on it,” groaned Audubon, sinking into a chair.

“That’s his privilege,” said Bowie.

“Why did thee do it?”

“I wasn’t going to listen to him blackguard you——”

“Me? I’ll thank thee to let me conduct my own affairs! Narcisse is my friend. He has been drinking, and in his cups his temper is uncertain, that is all. Besides, ’twas no more than I deserved. Most justly he berated me. But thee took it on thyself to intervene, thou great American oaf—and now——” He broke off, wringing his hands.

Bowie was speechless. Under the circumstances, he thought he had conducted himself rather well.

After a moment he said, “If that’s the way you think, we’d better part company right here. But just bear this in mind: he insulted me too.”

Audubon sat staring at the wine stains on the table, his face woebegone.

“Come, Nez Coupé,” Bowie said.

But the artist leaped up. “Wait! Nay, in God’s name we be friends!” He seized Bowie’s arm. “I’m on thy side, thee must believe me. I go with thee—we must think what to do.”

Bowie grunted. As they left the café, Nez Coupé said, “You should have leave me at him. The knife is more quicker than the pistol.”

“He had no pistol,” Bowie said. “If you’d knifed him, you’d have hung.”

Nez Coupé fell into sulky silence. Definitely, this was not according to Cajun notions of how an affair should be conducted.

“Already Narcisse has been principal in three duels,” Audubon said dolefully.

This was of interest. “Did he kill his men?” Bowie asked.

“Nay, wounded them, all three. One with the pistol, two with the sword.” Sudden hope in the artist’s face. “It’s by no means sure. Thee may escape with a wound only——”

Bowie laughed a short, ugly laugh. “If he and I fight, I’ll make you one promise: somebody’s going to get killed.”

It was like a pronouncement of a sentence of death. The artist shivered slightly, and said no more. Bowie turned toward the river.

2

Though it was Sunday, a brig with a cargo of rum from Havana was being unloaded by a gang of slaves at the Parisot wharf. Bowie watched the Negroes, moving in line like a colony of ants, save that they displayed none of the ants’ eager energy in their work. All were strong and muscular, outlandishly dressed in ragged dungarees and shirts of faded linsey, in each face the expressionless vacuity of the slave.

The spectacle was familiar. The dock hands trundled ahead of them two-handled, two-wheeled trucks, shuffling indolently, although a white man in a ship’s officer’s cap was yelling himself purple at them. Leaning against a stanchion with a coiled whip in his hand was a man in riding boots, with a black beard and a bloodless face: the overseer. He shared none of the mate’s excitement, but his eyes ceaselessly watched the slaves as each in turn received an oaken keg on his truck, and slowly trundled it back across the gangplank to the dock, where two of their fellows piled the fat casks high in an open warehouse.

Now and again Audubon glanced at Bowie. “What do we here?” he ventured at last.

“I’m hoping to find Monsieur Janos Parisot.”

“The merchant?”

“Yes. I have a letter of introduction from Judge Boden of Opelousas. Do you know him?”

“By sight.”

“Buys lumber?”

“Lumber—and many other things.”

“My two brothers and I own a lumber mill on the Bayou Boeuf,” Bowie said. “John and Rezin are older than I am. Older and steadier, I reckon. Rezin likes to hunt, but he has a practical side. He was the one who discovered the stand of timber on the Bayou Boeuf, but John worked out the details of setting up the saw pit and getting the lumber out.”

“And thee?”

Bowie half laughed. “I’m the youngest. And the longest-legged. And maybe the laziest.”

“Ha!” said Nez Coupé. “Jim take the pit end of the whipsaw an’ wear out both his brothair at the up end in a day’s work. Look at those shouldair! Jim get him from the whipsaw!”

“I work hard when I work,” Bowie said, “but I can’t see a life with nothing but the broadax and the whipsaw. I like to hunt. When I take a notion, I like to get my rifle and be gone for a few days.”

“Jim know every cabin an’ every pretty Cajun girl for forty mile around,” said Nez Coupé. “He nevair miss a cockfight, dance, broom jumpin’, or hunt——”

“Sounds bad, don’t it?” Bowie grinned. “John and Rezin used to sort of—well, talk with me—once in a while. Until I got big enough so’s I could handle ’em both. But we got along all right, until Dr. Carter Carter of Opelousas died. He was buying our lumber.”

“So thee seek now a new market?” asked Audubon.

“That’s correct. John’s about to get married, and Rezin’s in politics. So they sent me. That’s why I’m here right now—I’ve been told Parisot visits his dock every day.”

3

An hour passed. Audubon found a shady place, where he sat and talked with Nez Coupé. Bowie remained standing in the sun.

He became aware of a pair of loafers sitting on a coil of rope and watching the unloading with the peculiar enjoyment of loafers the world over at the observation of any kind of labor being done by others. In the manner, likewise, of all loafers, they made free with their comments.

“Wall, now,” said one, a tall bearded fellow in brown homespun, “if that ain’t the likeliest lot of niggers!”

“Not bad. No—I’d say purty fair,” agreed his companion, a fat bald man in a greasy nankeen shirt and leather breeches. It was obvious that they were river boatmen, and equally obvious that neither had ever owned so much as a single slave: yet they discussed the gang on the wharf in a large and expert manner, as elsewhere they might have discussed the fine points of a herd of cattle or horses.

“Nineteen,” said the brown beard. “Matched an’ in good shape. They’d fotch eight hundred dollars a head at a vendue.”

“A thousand’s more like it,” amended the bald one. “No—I’d say twenty thousand wouldn’t be no banter for the lot.”

“I dunno.” The brown beard had a wiseacre’s air. “Them looks like brute niggers, now. Right out of the Congo, I bet. None too well broke. Look at that rascal in the shed—troublemaker if I ever seed one.”

He referred to the nearer of the two slaves piling casks. Bowie glanced over. In contrast to the others, this man seized each burden and hoisted it to its place with a kind of savage energy. Yet he was weary: and something more. Through rents in his tattered shirt, Bowie saw ugly weals on the polished ebony body, and the shirt was stained with blood scarcely dry.

The slave had been flogged, no later than this morning, and severely: the kind of flogging that would have prostrated most men. Yet with a lacerated back he worked as none of the others worked, as if driven by some inner frenzy. Alone of them all he wore iron leg shackles, which confined him to short hobbling steps: and toward him, more often than to any of the others, the overseer turned his expressionless grim mask.

Bowie’s face showed no change. Slavery was accepted, and this man was another man’s property. But, contrary to the opinion of the loafers, the slave in the shed was no brute from the Congo.

Bowie knew him. Quite well. And from a happier time.

The loafers’ conversation took a new turn. “I know whar a gang like them kin be bought for no more’n a dollar a pound,” said the bald one. “Prime hands, all of ’em.”

“Aw, now! Whar?”

“Mebbe I ain’t sayin’.” These creatures loved to be mysterious.

“Huh! Ain’t no sech place. That’s why.”

The next remark fully caught Bowie’s attention.

“Mebbe,” craftily said he of the fatness and the baldness, “bein’ from Arkansaw, ye ain’t never heard of the Lafittes?”

“Hell, everybody knows about them pirates!”

“Some says they’re pirates: some says they ain’t. Mebbe they done a little piratin’—mebbe they done a little smugglin’. Ain’t for me to say.” Baldy closed an eye in an indescribable effort to look sly. “But some mighty high-toned gents right hyar in Noo Orl’ns was glad to be sociable with ’em at one time. An’ when ole Andy Jackson was fixin’ to scrimmage with the British down the perninsular, he warn’t too proud to have the Lafittes on his side.”

“Andy Jackson didn’t need no pirates to lick them Britishers!”

“Think not? Some’d argy that p’int with ye. An’ I’m thinkin’ Ole Hickory’d be one of ’em. Anyway, the Lafittes is gone now. Some place called Galvez-town, down the Texas coast.” The bald head became confidential. “Know who Dominique You is?”

“That ole sot? Shore. Everybody knows him.”

“Ole sot mebbe. But Cap’n Dominique was oncet the terror of the Gulf. I reckon he does h’ist enough licker to float him these days. But I ask ye, does he go around in rags? Not him. He eats an’ drinks at the very best places, drives a team of blooded bays, an’ keeps a fancy quadroon gal.”

Brown beard nodded. “That’s true. Never thought o’ that.”

“I bet ole Dominique could tell plenty, if he took a notion——”

“Looky. There’s Parisot comin’.”

Both loafers rose uneasily from their rope coil. “Reckon we better drift. He don’t fancy folks hangin’ around his dock.”

They slouched away around the corner of the warehouse.

4

The man approaching was past his prime, somewhat portly, with a heavy smooth-shaved face. He wore a long-tailed coat and high hat, walked with a cane, and with his free hand twirled incessantly a key which dangled from a heavy watch chain looped across his waistcoat. Parisot looked suspiciously at Bowie, and then called to the overseer.

“Peters!”

The man went to him, his manner typically respectful and impersonal.

“I’ve undertaken to clear the ship by morning,” said the merchant.

The overseer said, “We’re less than half finished, sir.”

“You’ll work tonight.”

“With this gang?”

“It’s all I can give you.”

The mouth behind the black beard tightened. “Very good, sir.” The overseer shook loose his whip, then coiled it again in his hand. Human endurance had limits, even to an overseer’s mind. But orders were orders. The braided lash of that whip would be wet with blood before the night’s driving was finished . . .

Bowie lifted his hat. “Are you Monsieur Parisot?”

“I am.”

“Then I have a letter addressed to you from Judge Sophocles Boden, of Opelousas.”

“I have the honor of Judge Boden’s acquaintance.” Parisot took the letter and scanned it. Bowie found little in him to like. “You are Mr. Bowie?” He extended a limp hand. “From the Bayou Boeuf? I know the country in general. H’mm—Judge Boden mentions that you’re in lumber.”

“I have a matter of business concerning that——”

“Pardon. I don’t transact business on Sunday—except a necessity like this unlading of a ship which has sailing orders.”

“I have reason for wishing to discuss matters with you today.”

“It will have to be an extraordinarily good reason, sir.”

Bowie smiled. “I may be killed tomorrow.”

“Did—did I understand you correctly?” Parisot gaped.

“I’m being called out by a gentleman of this city who is, I’m informed, accomplished with his weapons.”

“Oh, a duel?” Parisot nodded as one who finds the explanation less startling than he had thought. “What’s the nature of your proposal?”

“You purchase lumber?”

“Among other things—yes.”

“I am to inquire if you will take the output of a sawmill my brothers and I own together.”

“H’mm.” A hidden gleam of alertness came into the merchant’s eyes. In a casual manner he asked some questions. Bowie named a price.

Parisot fell silent, twirling his watch key. “I must have time to consider your proposition,” he said at last. “There are a few points that need examination.”

“Haven’t I made myself clear?”

“Perhaps. But always there are factors requiring further adjustment. I must consider the risks involved. As it happens, pine lumber is a drug on the market here. Of cypress, on the other hand, I could use all you can send. You suggest mixed shipments in equal quantities. Now if you were to furnish all cypress——”

“At the price I quoted?”

“Naturally.”

“Cypress is harder to log—and to saw—as you know, sir. Our price is shaved to the last penny. For cypress only I’d have to ask a higher figure.”

Parisot poked with his cane at a knot in one of the wharf planks. “You desire to establish an outlet in New Orleans? You should be prepared to make concessions.”

“The price I quoted was fair, sir.”

The merchant studied Bowie’s face. “Fair? What is fair? You’ve had small experience with trade, young man. I buy at the lowest price I can bargain and sell at the highest. You wish to settle the business before tomorrow—under the circumstances, these are my only terms.”

Bowie looked at the dock owner with a certain longing. But you cannot throttle a man simply because he won’t bargain your way. He changed the subject.

“These are your Negroes, Monsieur Parisot?”

“They are.”

“Nice lot.”

The merchant shrugged. “As good as one can get these days. It’s hard to buy prime hands since the government stopped the bringing of slaves into the country.”

“That fellow in the shed—where did you get him?”

Parisot turned his gaze in that direction. “That’s an example of what I say, Mr. Bowie. He was a house servant. My agent bought him at an auction, because he seemed likely. But he’s spoiled and uppity—spent too much time opening doors and polishing silver and pouring wine. Peters! You’ve had trouble again with that man Sam?”

“Yes, sir,” the overseer said. “Had to give him a taste of the snake whip this morning.”

The overseer spoke with the icy detachment of his class, handlers of human flesh and blood, whose profession was to accomplish certain things with the units in their charge, using whatever methods were needful to stimulate them to the results desired.

“A bad actor,” said Parisot petulantly. “And he can ruin the others. Thinks he’s got rights—like resting on Sunday.”

“A few weeks in a breaking camp might be good for him,” said Peters. Merchant and overseer frowned over at the slave.

“He seems to work hard enough,” Bowie said.

“When he has to,” said Parisot.

“If he’s a trained house servant, why put him at common labor?”

“Because I need hands, not house servants!” The merchant turned to the overseer. “Peters, I’m out of patience. That rascal’s acted up once too often. Get hold of the factors tomorrow, and turn him over to the breaking camp. I want the fear of God put into him!”

He said it with a peculiar gloating ferocity. Work had ceased momentarily while the hoists brought up more cargo from the hold, and Bowie knew the slave had overheard him.

The implications were sufficiently shocking. Operations of the so-called “breaking camps” down in the Delta were carefully hushed up in Louisiana, but rumors concerning them had circulated for years: whispered stories of strange secret horrors, where the lash sounded day and night, and starvation, the water cure, the thumbscrew, the branding iron—all forms of torment that did not break or maim yet gave exquisite anguish—were employed to destroy any “spirit” in the unfortunates held there, particularly those newly imported from the Guinea coast or the Congo. Bowie had heard of the shocking “wastage” in the breaking process, the deaths and suicides: and how miserable victims who managed somehow to survive came out of the hell-camps little better than idiots, their minds gone, capable all their lives of but one emotion—fear.

The slave called Sam had listened with the terrible fascination of those who are certain of a ghastly doom, yet await final pronouncement of their sentences. Bowie found himself suddenly very unwilling to have this man sent to a breaking camp.

“You got him at the Carter plantation sale?” he asked Parisot.

“I believe so.”

“I was acquainted with Dr. Carter Carter prior to his death. A conspicuous gentleman in his day.”

“Yes. Most unfortunate that he died without direct heirs. An ornament to the country, Carter Hall, and it had to be broken up——”

“It happens I know this man of yours. He was Dr. Carter’s butler. I have a fancy to take him off your hands.”

The gleam of alertness flickered again in Parisot’s eye, instantly disappearing. He shook his head. “Sorry. He’s not for sale.”

“Name a price.”

“I said he was not for sale.”

“You spoke of sending him to a breaking camp.”

“I did.”

“It might kill him.”

“A risk I have to take.”

“He’d be little use to you then.” Bowie hesitated. “Would you trade him?”

“For another slave?” Parisot was crafty. “Not for a brute nigger fresh out of Africa.”

“Would you trade for two?”

Parisot grew smooth. “Age and condition?”

“Equal or better.”

“When?”

“It would take a little time.”

“Days?”

“Six months.”

Parisot thought. “If you mean it, there can be but one answer. I agree.”

“Good. I’ll take the man with me now.”

The merchant grinned humoringly. “You’re joking. Where’s the exchange?”

“My personal note of hand.”

“With all apologies, my young friend, I’m afraid a personal note from you wouldn’t be very negotiable in these times.”

“As security, my one-third of the lumbering concern on the Bayou Boeuf.”

Parisot studied him. “You seem to want this slave badly.”

“I need a valet.”

“Very well. Step to my office. We’ll draw up the papers.”

“Let me speak to the slave first.”

“Certainly.” At Parisot’s nod the overseer made a motion of his coiled whip and the Negro clanked toward them with his shackles. He was tall and strong, with a slight grizzle at his temples, and a black face which was intelligent, if at the moment bleak and sullen. Bowie could remember that face when it was lit with a smile of welcome at Dr. Carter’s hospitable door.

“Sam,” he said.

“Marse Bowie, suh.” The slave was deferential, yet dignified, in spite of his weariness and pain.

“I’m buying you from Monsieur Parisot.”

Sam’s eyes flicked to the merchant, to the overseer, then back to Bowie. “Yes, suh,” he said. Then, as if the full significance of it had just dawned, “Yes, suh, Marse Bowie!”

Bowie looked at Peters. “Have those shackles off of him.”

The overseer glanced at Parisot.

“You hear him,” the merchant said.

The man with the black beard nodded impassively. He was a slave overseer, and such men were trained to feel no more human emotion in themselves than they recognized in the slaves under them. He began to unlock the irons on Sam’s ankles.

Chapter Four

1

Henri Pinchon, owner of the Rouge et Noir tavern, sat in his usual place at his desk which stood behind the bar. On the wall above his head hung a row of large bells, each with a bullet-shaped tongue which, when pulled, continued to vibrate for some minutes after ringing, thus showing to which room above it belonged. Pinchon was short and round, the almost type-perfect host, since he loved his joint and bottle as well as any of his guests, and prided himself on his ability to estimate character at first sight.

For the moment, however, his usual complacency was gone. He had been filled with surprising inner doubts as to his judgment on one customer at least: this Monsieur Bowie. The previous day when he had come to the tavern, Henri ticketed him as a greenhorn who knew not good from bad. The appearance of the scar-faced little Cajun with him confirmed that opinion. The two, therefore, had been assigned the smallest room in the inn, high under the eaves overlooking a dirty courtyard, where they shared a very lumpy bed. Now the good Henri wondered . . .

He rose quickly to his feet. The very pair had entered the public room, accompanied by a man in purplish drab who looked shabby as a beggar, and followed by a Negro in a field hand’s ragged linsey. How was a tavernkeeper to conduct himself toward these people?

“Monsieur Bowie——” he said in a low voice. He leaned confidentially over the bar, and Bowie had a whiff of garlic from his breath. “Two gentlemen are here, desiring to see you.”

“Who?”

“They are—of the élite.” Henri rolled his eyes toward the chimney corner and his voice was tinged with respect. The quality of these visitors was sufficiently impressive to give a guest standing merely because such personages saw fit to call upon him.

Bowie turned. Two young men rose and bowed to him together. One he recognized: the long, petulant lip and thin mustache were not easily forgotten. Friends of that fire-eating Creole, Narcisse de Bornay, and their business was not difficult to guess.

He walked across the room, and spoke in French. “You wish to see me?”

He of the mustache answered. “There was hardly time for a formal exchange of names at our first meeting, Monsieur Bowie. Allow me, therefore, to introduce my friend and myself. This gentleman is Monsieur Armand Lebain. I am Philippe Cabanal.”

“Your servant, messieurs,” murmured Bowie, bowing. Lebain appeared to be an ineffectual young man, round-chinned, soft-lipped and proud.

“May we speak in private?” Cabanal asked. “I have taken the liberty of arranging with Pinchon for the small sitting room——”

“If you wish. My friends?”

“Certainement.”

Sam, the slave, effaced himself in a corner. With Audubon and Nez Coupé, Bowie followed the visitors to a small room off the main hall, where they turned to him politely.

“We are here on behalf on Monsieur de Bornay,” Cabanal said.

Bowie nodded.

“He has empowered us to arrange terms—in the matter of which you know—according to your satisfaction, since you are the challenged party,” continued the Creole stiffly.

Another nod from Bowie.

A moment’s awkward pause. Then, as if it were distasteful, “Our principal, monsieur, desires us to inquire in what manner you wish his apology to be delivered.”

It caught Bowie so by surprise that he wondered if he had heard rightly. “Apology?” he echoed, somewhat stupidly.

“Yes, monsieur.”

“I—I believe I do not understand——”

Cabanal drew himself up. “Monsieur de Bornay is a gentleman whose courage has never been questioned. Let that be understood at once. He also has a—let us say an unusual sense of honor—which sometimes induces him to act in an extraordinary manner, or so some of us feel.” He paused, as if to convey to Bowie that he, for one, did not approve of what was to follow. “In this instance, he requested us to inform you that realizing he was—ah—somewhat intoxicated this noon, and considering his actions, he feels it your due—and his own also as a gentleman—that he offer his apologies.”

This was so utterly contrary to any experience that Bowie could not bring his bewildered mind to frame a reply.

“You are willing to accept the apology?” asked Cabanal, after a moment.

“Why—I suppose so——”

“In that case,” the Creole said, “we are to ask if you require that it be put in writing, or made to you verbally, in person.”

Bowie could have laughed. But the chill formality of the two before him caused him to pick his words carefully. “As to that,” he said, “for myself I require no apology at all. If Monsieur de Bornay wishes to retract his words, let him do so to Monsieur Audubon.”

“He will do so. Is that all?”

“Yes.”

The Creoles stepped to one side and conferred for a moment in low voices. Then they were back, stiff and formal, Cabanal the spokesman as before.

“Permit us to say, monsieur, that we consider this magnanimous of you, especially since it was the purpose of Monsieur de Bornay, who esteems Monsieur Audubon, to make such retraction in his own instance.”

He and Lebain bowed. “Now, since so much is agreed between us, shall we proceed to the next part of the business?”

Once more Bowie was baffled. “What other part is there?”

“But surely it is for you now to name to us your seconds, so that the place of meeting and also the weapons can be determined?”

Bowie simply stared. Were these young fools insane?

“Let me understand,” he said. “Did I not hear you say that Monsieur de Bornay offers his apologies?”

“Vraiment.”

“Then—would that not appear to be an end to the quarrel?”

“Monsieur does our principal less than justice,” said Cabanal loftily. “He would never dream of depriving you of the right of upholding your honor against him at the full risk of his own body.”

Astonishing, these Creoles, certainly. Bowie was between admiration and exasperation at a man who could think up a dilemma so outrageously contradictory. And the more he considered it, the more reluctant he found himself to fight a duel with an opponent so remarkably inclined, so he said, “Please to inform your principal that my honor is not affronted: and for my part there need be no meeting at all.”

Once more they bowed. “We trust this is not merely further magnanimity. He is very ready——”

Bowie exploded at last with laughter. “If he must fight, I’ll name you the time and weapons! The time: when next it snows in New Orleans——”

“But it never snows in New Orleans——”

“I’m aware of that. The weapons: snowballs——”

“Monsieur——”

“Meantime, present my compliments to Monsieur de Bornay, and tell him that I would esteem it a privilege to shake his hand and so close the entire affair—which I’m very ready to say he has conducted in a manner that does him an infinite amount of credit.”

The Creoles were unsmiling. In the American’s manner was a suspicious levity. His message, moreover, seemed hardly couched in the proper terms. Yet there was something so clifflike in this fair-haired young giant that further arguments did not occur to them.

After a moment they bowed stiffly and withdrew.

2

Bowie found a very respectful Henri Pinchon awaiting him. The gentleman desired another pallet in his room? But certainly. Quarters for the slave? On learning that what apparently was a raw field hand in reality was a skilled house servant, Henri had a proposal. He could employ Sam in the dining room, thus defraying the extra cost of Audubon’s lodgings. Bowie accepted.

But when they went up to their third-flight room, Nez Coupé was still snorting. “These peoples—nom du chien—too much talk, bah! Lots of time Cajun fight—sometime with gun—sometime with feet—la savate—sometime with knife. Like this——” He indicated his scarred visage. “Auguste Cabet—he give me that one. Good frien’, Auguste.”

“Good friend when he did that to thee?” asked Audubon.

“Oh, Auguste like me plenty.” Nez Coupé laughed merrily, as if a disfigured nose was a small matter. “We drunk that time we fight. Me, I fix Auguste so he have stiff arm always. Good fight, that one. An’ no talk—like here.” Nez Coupé went through a ridiculous little mincing routine of bows and posturings, meantime repeating such words as he could remember of the formal utterances he had heard. “Monsieur. We arrange term. We have priv’lege. He reques’ we inform you. Permit us. Magna-magnam—what is this word? Bah!” His scarred face was contemptuous. “Big word get nowheres. Auguste an’ me—we get plenty drunk. We fight. No big word. When we get well, we go hunt together like before. We make lots of fun, us.”

Bowie sat moodily silent.

“What ails thee, James?” asked Audubon.

“Nothing.”

“Assuredly something does.”

“I’ve been a fool.”

“In what manner?”

“In every way a man could, I reckon.” Bowie gave a short laugh.

“How so? The outcome of the quarrel was most happy——”

“I’m not even thinking about that. This afternoon’s what’s eating me. It just come over me what a trap Janos Parisot led me into. Played on my sympathies—the old reptile—until I ruined any chance I had for a good deal—obligated myself for everything I own and more—went into debt for fifteen hundred dollars—and all to buy a nigger I’ve got no more use for than a second set of teeth!”

“Why did thee do it, James?”

Bowie thought back. He had not acted entirely without plan. A sudden secret scheme had suggested itself, endowing him with that surprising calmness in talking to Parisot. But already he was realizing how hare-brained that scheme was. Too ridiculous even to mention.